2024-116 Office of AIDS

Further Improvements to Its Contract Management Processes Are Needed to Reduce the Risk of Fraud

Published: July 24, 2025Report Number: 2024-116

July 24, 2025

2024-116

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, CA 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Office of AIDS (OA) within the California Department of Public Health. Our assessment focused on the OA’s role coordinating state programs, services, and activities relating to HIV/AIDS. In general, we determined that although the OA has made notable progress to address administrative weaknesses that were significant to the fraud that occurred from December 2017 through November 2018, its invoice review process remains susceptible to fraud. Despite the OA developing an invoice review process that requires staff to verify that the amounts contractors invoice are based on supporting documentation and which also requires multiple levels of review before payment, we remain concerned that the OA does not require its staff to collect comprehensive documentation that substantiates subcontractor expenses. Lacking this practice, the OA remains exposed to risks similar to those that led to the prior fraud.

My office also found that although the OA generally allocates funding appropriately—using relevant data and following federal and state guidelines—it lacks standardized processes to assess whether local health jurisdictions and community-based organizations use that funding efficiently and, in some cases, allowably. As a result of this absence of oversight, the OA cannot measure whether these entities use their allocations in the most efficient manner. For example, the OA fell short in ensuring the effectiveness and oversight of its Housing Plus Project, for which it did not monitor whether service providers adequately verified the eligibility of the clients they served. We recommend that the OA strengthen its monitoring of subcontractor expenses and adopt more systematic methods to evaluate program efficiency and outcomes. These steps are essential to safeguard the continued integrity and impact of the State’s HIV/AIDS programs.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ADAP | AIDS Drug Assistance Program |

| AIDS | Acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| ARIES | AIDS Regional Information and Evaluation System |

| CAPS | Contracting and Purchasing System |

| CBO | Community-based organizations |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CPG | California Planning Group |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HOPWA | Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS |

| HRSA | Health Resources and Services Administration |

| HUD | U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| NHBS | National HIV Behavioral Surveillance |

| OA | Office of AIDS |

| OLS | Office of Legal Services |

| PrEP | Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| Public Health | California Department of Public Health |

Summary of Key Findings

The Office of AIDS (OA) is a division within the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) and is responsible for coordinating state programs, services, and activities relating to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and AIDS-related conditions. The OA comprises the division office and six branches, and allocates funding to local health jurisdictions (jurisdictions) and community-based organizations (CBOs) to support various services related to HIV and AIDS. As a result of fraud perpetrated by certain OA staff from December 2017 through November 2018, Public Health engaged a financial advisory services consultant to review internal controls and compliance with administrative procedures, among other things. That review, as well as other reviews and audits conducted since then, resulted in recommendations to improve various aspects of the OA’s operation. This audit focuses on evaluating the OA’s progress toward addressing those recommendations, as well as reviewing its role coordinating state programs, services, and activities relating to HIV and AIDS.

Key Findings

- Although the OA has resolved many of the audit findings it received during the past five years, its invoice review process remains susceptible to fraud.

- Public Health has not developed clear guidance to ensure that the OA acts on the feedback that it receives from the Award Compliance Unit (compliance unit) regarding opportunities for the OA to improve its contract management practices.

- The OA ensures that its funding is allocated according to funding requirements and distributed according to geographic need as it determines by reviewing relevant data sources, but the OA does not have a standardized process to measure whether jurisdictions and CBOs use their allocations efficiently.

- The OA takes actions while monitoring contractor performance to ensure that jurisdictions and CBOs adhere to their contracted statements of work and budgets that include communicating guidance through feedback on progress reporting, delaying payment of invoices, and requiring corrective action plans in response to site visit evaluations.

- The OA takes corrective action with its contractors based on the findings of the compliance unit, including requesting repayment for amounts the OA may have paid to a contractor for unallowable expenses.

- The OA has not determined the effectiveness of the Housing Plus Project (Housing Project) and does not have plans to continue the program. Moreover, the OA did not systematically review whether Housing Project providers adhered to the program’s eligibility requirements, and it could not always substantiate whether program funds were used for allowable purposes.

Agency Comments

Public Health agreed with our recommendations and stated that it plans to implement them.

Background

The Legislature Established the OA as the Lead State Agency for HIV and AIDS Related Programs

The OA is a division within Public Health’s Center for Infectious Diseases. Its mission involves addressing the needs of Californians related to HIV and AIDS, as the text box shows. The Legislature established the OA as the lead agency within the State responsible for coordinating state programs, services, and activities relating to HIV, AIDS, and AIDS-related conditions. As Figure 1 shows, the OA comprises the division office and six branches that each serve a specific function.

The OA’s Mission

- Assess, prevent, and interrupt the transmission of HIV and provide for the needs of infected Californians by identifying the scope and extent of HIV infection and the needs which it creates, and by disseminating timely and complete information.

- Assure high-quality preventive, early intervention, and care services that are appropriate, accessible, and cost effective.

- Promote the effective use of available resources through research, planning, coordination, and evaluation.

- Provide leadership through a collaborative process of policy and program development, implementation and evaluation.

Source: The OA’s website.

Figure 1

The OA Comprises a Division Office and Six Branches

Source: The OA’s website.

The Office of AIDS Division office oversees the following six branches:

Support Branch: Performs administrative functions that support OA program areas, including budgets, personnel, contracts, grants, clerical support, information technology, procurement, and business services. Surveillance Branch: Conducts a variety of epidemiologic studies, evaluates the efficiency and effectiveness of publicly funded HIV and AIDS prevention and care programs, and maintains California’s HIV and AIDS Case Registry. Care Branch: Oversees programs related to the delivery of care, treatment, and support services for people living with HIV or AIDS. Prevention Branch: Funds initiatives to assist local health departments and other HIV service providers to implement effective HIV detection and prevention programs. AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) Branch: Helps ensure that people living with HIV and AIDS who are uninsured and under-insured have access to medication. ADAP and Care Evaluation and Informatics Branch: Oversees data collection, reporting, quality improvement, program monitoring and scientific evaluation for the ADAP and Care Programs.

The OA Receives Funding From Federal Funds and the State General Fund

During fiscal year 2023–24, the OA spent approximately $480 million in federal and state funds. The text box lists federal programs providing funds to the OA.

Federal Programs Providing Funds to the Office of AIDS

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS

Health Resources and Services Administration Programs

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program

- AIDS Drug Assistance Program Shortfall Relief

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Programs

- Medical Monitoring Project

- Integrated HIV Surveillance and Prevention Programs for Health Departments

- National HIV Behavioral Surveillance

Source: OA financial documentation.

The OA may face impacts from federal funding changes based on the federal government’s budget proposal for fiscal year 2026. In May 2025, the federal Office of Management and Budget released a list of budgetary requests for the federal fiscal year 2026 budget proposal that reduces funding for multiple programs. For example, it proposes reductions to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) programs of more than $3.5 billion. For fiscal year 2023–24, the OA received more than $33 million in CDC funding from programs such as those shown in the text box. If the federal fiscal year 2026 budget proposal is approved, California may see reductions in its CDC funding.

The OA’s HIV Care Branch (Care Branch), HIV Prevention Branch (Prevention Branch), and Surveillance and Prevention Evaluation and Reporting Branch (Surveillance Branch) allocate various state and federal funding to jurisdictions and CBOs throughout California. For fiscal year 2024–25, the OA was budgeted approximately $52 million for administrative expenses and $476 million for local assistance funding, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2

The Majority of the OA’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2024–25 Focused on Local Assistance Efforts

Source: State of California HIV/AIDS Program Funding Detail, Enacted 2024 Budget Act.

The OA’s local assistance budget included the following amounts: The AIDS Drug assistance program receives $400 million. Prevention and Testing receives $35 million. Care and Support receives $29 million. Housing receives $5 million.

Epidemiologic Studies/Surveillance receives $7 million. Local assistance is expenditures made for the support of local government or other local administered activities. The OA also budgeted $52 million for administrative expenses.

Some OA Employees Engaged in a Multimillion Dollar Fraud Scheme in 2017 and 2018

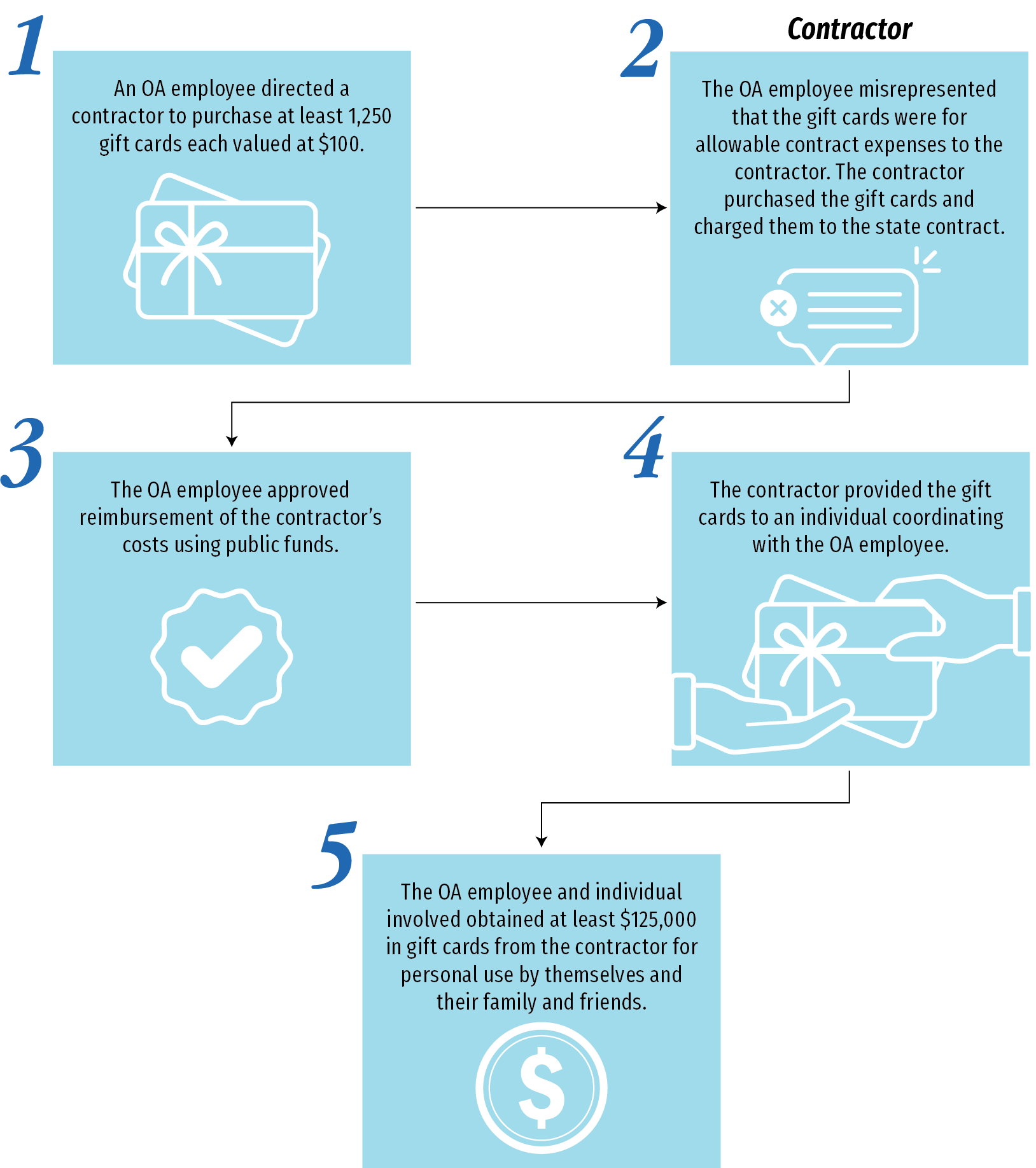

From about December 2017 through November 2018, two OA employees participated in a scheme coordinated by a third employee to defraud the State by diverting OA funds to obtain at least approximately $2.7 million in personal benefits. Based on the employees’ plea agreements, one element of the scheme occurred when an OA employee caused a contractor to pay for personal expenses the employee accrued using the contractor’s debit cards. To achieve this, the OA employee emailed a spreadsheet to the contractor confirming that the personal transactions should be designated as expenses under the service contract with the OA. When the employee received the invoices that included false expenses from the contractor, the employee repeatedly signed on behalf of the OA to approve their payment, and the contractor was thereafter paid with public funds. Thus, the employee essentially received government funds via the contractor. This aspect of the fraud was able to occur because, as we discuss further in the Audit Results, the OA had not established important controls to ensure that invoices the State paid were for services actually rendered. Additionally, in furtherance of the scheme, the participants created two shell companies that submitted invoices to the state contractor for work that was never performed. Shell companies are companies that do not do or own anything, but they can be used to hide a person’s or another company’s activities. The contractor then paid the invoices and sought reimbursement from the OA by charging those payments to the state contract. Because payments to the two shell companies were actually directed to bank accounts that were controlled by individuals participating in the fraud, the OA employees were able to access government funds for personal use. Figure 3 shows another aspect of this fraud scheme. Although we found no record of charges filed against the contractor or its known officers, we did find that the company was dissolved in October 2019. The Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted the investigation into the fraud with assistance from Public Health and the California Highway Patrol. Those former employees were charged with fraud and ultimately pled guilty.

Figure 3

OA Funds Were Used to Purchase Gift Cards for Improper Personal Use

Source: Plea agreements.

The following actions account for how the gift cards were obtained: An OA employee directed a contractor to purchase at least 1,250 gift cards each valued at $100. The OA employee misrepresented that the gift cards were for allowable contract expenses to the contractor. The contractor purchased the gift cards and charged them to the state contract. The OA employee approved reimbursement of contractor’s costs using state funds. The contractor provided the gift cards to an individual coordinating with the OA employee. The OA employee and individual involved obtained at least $125,000 in gift cards from the contractor for personal use by themselves and their family and friends.

As a result of the fraudulent activity, Public Health commissioned Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP (Deloitte) in December 2018 to assess and investigate the procurement systems, payment business practices, and supporting control processes within OA, and to make recommendations for improving controls across various aspects of the OA’s operation. In June 2019, Deloitte reported that it found multiple internal control weaknesses in the OA’s Prevention Branch, the branch where the fraud occurred. These internal control deficiencies are addressed in the next section. In 2024, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed the California State Auditor’s Office to conduct this audit to determine whether the OA has taken adequate steps to implement Deloitte’s recommendations and prevent future fraud schemes from occurring.

Audit Results

- Has the OA corrected prior audit findings, including how it monitors payments to contractors? (Objective 2)

- How does the OA determine the funding amounts it provides to jurisdictions and CBOs, and how does it measure program efficiency? (Objective 3)

- Has the OA established a reasonable process for taking action when it finds jurisdictions and CBOs that are not using their allocations to adequately deliver services? (Objective 4)

- Does the OA use funds for outreach and education appropriately and effectively?(Objective 5)

- Is the OA’s methodology for allocating funding under the HIV Surveillance Program equitable?(Objective 6)

- Has the OA effectively managed the Housing Plus Project including collecting, reviewing, and using the results from the program?(Objective 7)

- Has the California Planning Group fulfilled its responsibilities related to coordinating state HIV/AIDS programs, services, and activities?(Objective 8)

- How do jurisdictions and CBOs believe the OA could improve, and what challenges affect their delivery of OA services and programs?(Objective 9)

Audit Objective 2 (summarized):

Has the OA corrected prior audit findings, including how it monitors payments to contractors?

KEY POINTS

- The Office of AIDS (OA) has corrected its past audit findings, including implementing Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP’s (Deloitte) recommendations, which the OA addressed by establishing contract management policies and procedures that require multiple levels of review and approval to pay an invoice or to create or amend a contract. In doing so, the OA eliminated administrative weaknesses that were significant to the fraud activities that occurred in 2017 and 2018.

- Despite correcting its past audit findings, including implementing Deloitte’s recommendations, the OA is still susceptible to fraud risk because it does not verify work performed by its contractors’ subcontractors.

- The OA is missing opportunities to further improve its processes because there is no oversight mechanism to ensure that the Award Compliance Unit (compliance unit) communicates program improvement feedback to the OA or that the OA consistently acts on such feedback. The California Department of Public Health (Public Health) could underscore the importance of the relationship between the OA and the compliance unit by establishing policies to ensure that the compliance unit consistently shares all of the feedback to the OA that Public Health would like the OA to act on.

The OA Has Corrected Its Past Audit Findings, Including Those That Addressed Administrative Weaknesses Underlying the Fraud It Experienced From 2017 Through 2018

The OA has taken steps to address the audit findings that it has received since June 2019. From June 2019 through September 2024, Deloitte and other entities, such as the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—federal entities that provide funding for various OA programs—have conducted reviews or audits of the OA. These reviews and audits reported weaknesses in the OA’s contract management oversight and general administration processes. Deloitte’s review specifically addressed administrative weaknesses that likely enabled the fraud activities that occurred in 2017 and 2018. State law establishes the responsibility of agency heads to ensure that their agencies promptly resolve the findings of audits, and we found the OA has done so. The OA received 19 unique findings from the various audits and reviews that we evaluated—seven from the Deloitte review and 12 from the other audits. The OA has resolved 15 of these 19 findings, with one finding from the most recent HUD report that is partially implemented and three findings from the most recent HRSA report still pending resolution. Appendix A includes a table that lists the unique audit findings that the OA has received since June 2019 and our evaluation of whether the OA has resolved each finding. In the remainder of this section, we focus on how the OA addressed Deloitte’s findings because they were more directly related to the fraud than the other findings the OA received.1

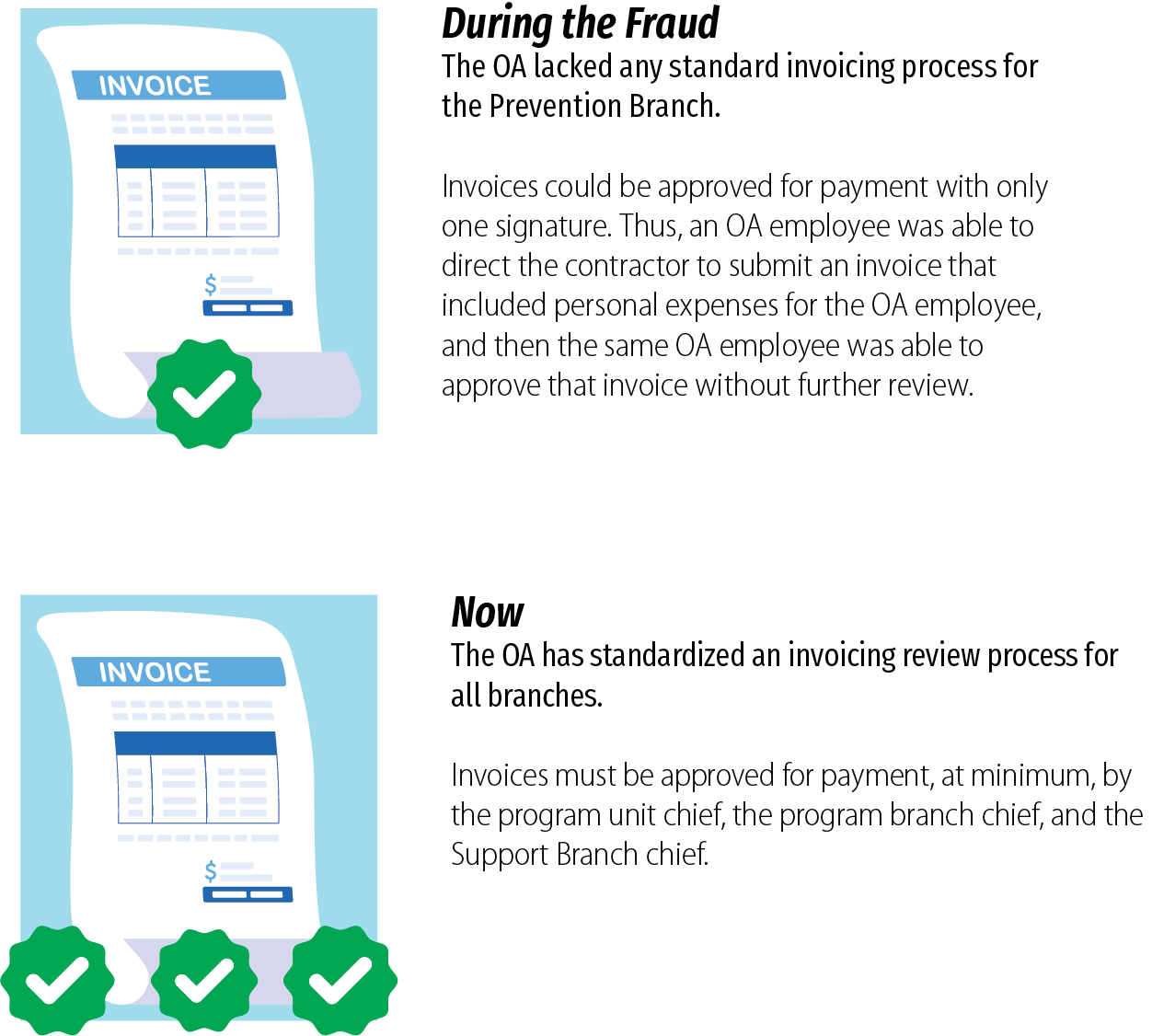

Deloitte reported findings that identified several weaknesses that we think contributed to the fraud that occurred within the OA in 2017 and 2018. One weakness Deloitte identified was that the Prevention Branch had neither a standard invoicing process, nor did it have any administrative controls over its invoice approvals. The text box lists administrative controls that Deloitte reported were missing from the OA, and the absence of which likely enabled the fraud activities. Part of the fraud involved a contractor that was able to submit invoices to the OA that claimed to be for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention services but actually included an OA employee’s personal expenses and lacked any evidence to support the services that were supposedly provided. The same OA employee then approved those invoices to be paid without anyone else critically reviewing the transaction. To address its findings, Deloitte recommended that the OA determine and memorialize a standard set of requirements for its staff to follow when approving invoices that included designating a central point of contact within the Prevention Branch to receive and provide invoices to the Support Branch and a procedure to reconcile invoice amounts to the contract budget and terms.

OA Invoice Approval Weaknesses in the Prevention Branch at the Time of the Fraud

- No routing guidelines for invoices it received.

- No timelines or expected due dates for submitting invoices to the Support Branch.

- Inconsistent invoice logging and tracking.

- No control to ensure that the appropriate level of approval had been completed before invoices could be processed for payment.

Source: The Deloitte report.

The OA developed an invoice review process that includes the invoice approval elements that Deloitte recommended. Figure 4 shows that the OA created a standard invoice review process applicable to all of its branches that requires staff to review the contractor’s supporting documentation and generally requires, at a minimum, the program unit chief and the program branch chief to approve and route all invoices to the Support Branch chief for approval prior to payment. The procedures require program reviewers to verify that the amounts invoiced by contractors are accurate, are based on the supporting documentation, and are expenses that the funding source allows. The procedures also establish a 15-day timeline to complete the reviews. By requiring invoices to pass through multiple levels of review that include confirming that the expensed amounts are supported and allowable, the OA acts to prevent a single person from fraudulently colluding with a contractor to receive reimbursement for expenses for activities not allowed by the contract. Since the OA implemented these procedures, it has also reduced the amount of time that it takes to process an invoice by two-thirds, including any time spent working with contractors to resolve issues that it identified while reviewing the invoices. Specifically, the OA went from spending an average of 62 days to process invoices that it received in 2020 to an average of 21 days for invoices that it received in 2024. This increased speed of processing invoices is likely the result of the OA’s invoice procedures requiring staff to complete reviews within 15 days of receiving an invoice. We discuss our evaluation of the OA’s implementation of its updated invoice review process in Objective 4.

Figure 4

The OA Has Implemented a Standardized Invoice Review Process That Addresses Weaknesses That the Fraud Scheme Relied on to Operate

Source: The Deloitte report, federal court documents, and the OA’s February 2024 administrative procedures.

Note: We discuss the results of our testing of whether the OA has consistently implemented this new invoice review process in Objective 4.

During the fraud, the OA lacked any standard invoicing process for the Prevention Branch. Invoices could be approved for payment with only one signature. Thus, an OA employee was able to direct the contractor to submit an invoice that included personal expenses for the OA employee, and then the same OA employee was able to approve that invoice without further review. Now, the OA has standardized an invoicing review process for all branches. Invoices must be approved for payment, at minimum, by the program unit chief, the program branch chief, and the Support Branch chief.

Deloitte also found that the OA’s general contracting procedures lacked a structured approval process for new contracts and contract amendments. Between January 2018 and July 2018, the OA amended the contract that was used to perpetrate the fraud three times to extend the term of the contract by one year and increase its value from approximately $5 million to $22 million. This action provided an opportunity for the perpetrators to prolong their fraudulent activity and could have resulted in additional unallowable expenses as the amended contract provided an additional $17 million that the contractor could invoice the OA. The current OA division chief acknowledged that a contract of this size is suspicious and atypical compared to other Public Health contracts. Given the atypical nature of the contract amount, had the amendments required multiple levels of management review and approval prior to execution, there would have been a greater likelihood that one or more reviewers would have questioned the appropriateness of the value increases and discovered the fraud sooner. However, at the time the contract was amended, the OA did not have a structured process for reviewing and approving new contracts and amendments and thus was not consistently reviewing contracts or amendments before approving them. Consequently, Deloitte recommended that at least two levels of management should be required to review and approve each contract and contract amendment.

The OA also developed procurement procedures that address this recommendation. Figure 5 indicates that in response to the recommendation, the OA developed standardized procurement procedures for contracts and for amendments that increase the amount of a contract. These new procedures generally establish six levels of program and management review and approval within the OA, including approval from the OA division chief. This process ensures that the OA’s approval requirements must be satisfied and documented on the routing slip that accompanies each agreement before any agreement can be executed and recorded in Public Health’s contract management system. Requiring multiple layers of OA management approval for contracts and amendments should deter individuals from proposing contract amendments that substantially increase the contract’s value without appropriate justification. By standardizing and memorializing its contract and contract amendment approval processes, the OA has also fully implemented Deloitte’s recommendations to document such procedures. We also tested the OA’s implementation of its updated contract approval processes by reviewing the contract approval slips for a selection of 40 contracts. We found that the OA followed its updated approval processes in all cases.

Figure 5

The OA Has Implemented a Standardized Contract and Amendment Approval Process That Addresses Weaknesses That Allowed the Fraud Scheme to Continue

Source: The Deloitte report, the OA’s contract approval documentation, and the OA’s February 2024 administrative procedures.

During the fraud, the OA lacked any structured approval process for new contracts and amendments. As a result, the OA was not consistently reviewing contracts or amendments before approving them. The OA amended the contract that funded the fraud three times within six months to extend the contract by one year and to increase the value of the contract from approximately $5 million to $22 million. Now, the OA has developed written procurement procedures for contract and amendment approvals. All contracts and amendments that change the cost of the contract generally require six levels of program and management review and approval within OA.

Despite addressing the Deloitte report’s recommendations, the OA is still susceptible to fraud because it does not verify the work performed by its contractors’ subcontractors. As we described earlier in this section, the OA now requires its staff to review supporting documentation to verify the accuracy of contractor invoices and that all expenses are for uses that their funding source allows. For example, for one program, the OA requires contractors to submit documents that support their operating expenses, like store receipts for purchases, and another program requires documents such as time and attendance records to support personnel costs. For all programs, when reviewing invoices, the OA requires that the totals from supporting documentation match the invoice amounts and that the expenses claimed are an allowable use of funds for their funding source. By collecting and reviewing this level of supporting documentation, the OA is able to verify that items were purchased and were allowable. However, the OA does not collect or review a similar level of documentation for its contractors’ subcontractor expenses in any of its branches or programs. When a contractor uses a subcontractor, the OA only requires its contractors to submit subcontractor invoices, rather than supporting documentation for those subcontracted expenses. This requirement is problematic because it allows contractors to submit an itemization of subcontractor costs without evidence to demonstrate that those costs were actually incurred and were for allowable purposes, which can raise concerns about whether fraudulent payments to subcontractors would be detected.

OA management explained that the OA does not require its staff to collect or review subcontractor documentation. Figure 6 shows that a significant aspect of the previous fraud scheme involved OA staff creating shell companies and using them to submit falsified invoices to an OA contractor, which would pay the shell companies and later seek reimbursement from the OA by charging those payments to the state contract. Additionally, the State Administrative Manual requires state agencies to determine whether goods or services invoiced to the agency have been received or provided. Consequently, even though Deloitte did not specifically recommend the OA begin verifying subcontractor expenses, we expected that the OA would have taken measures to act to prevent future fraudulent activity of this kind.

Figure 6

The Fraud Scheme Utilized Fictitious Subcontractor Expenses

Source: The Deloitte report and federal court documents.

One aspect of the fraud occurred through the following transactions: Shell companies invoiced the OA contractor. Two shell companies, established by participants in the fraud scheme, posed as legitimate subcontractors and submitted fictitious invoices that falsely claimed to be for legitimate services to the OA contractor for payment. One shell company claimed to provide consulting and meeting facilitation services. The second shell company claimed to provide website and information technology services, including performing work on a website named PleasePrEPMe.org. The OA contractor paid the shell companies. The contractor paid these subcontractor invoices for their falsely claimed services. The OA contractor invoiced the OA. The contractor submitted invoices for its expenses, including the fraudulent subcontractor expenses, to the OA for payment. The contractor was contracted by the OA to provide condoms and other harm reduction supplies. The OA also used the contractor as an intermediary, whereas the contractor would receive state funds to pay invoices from other OA contractors. The OA paid these contractor invoices. The contractor submitted invoices to the OA that claimed to be for legitimate services. The OA employee involved in the fraud then approved those invoices to be paid, and the Prevention Branch did not conduct any additional review to verify whether services listed by contractors or subcontractors were provided. At least $1,476,000 was lost through the false subcontractor mechanism of the fraud scheme.

For example, the OA could require its staff to collect documentation from its contractors that supports the subcontractor staff hours spent on the contract and receipts underlying the subcontractors’ operating expenses—both pieces of supporting documentation that the OA collects from its contractors to substantiate their costs. By not requiring its staff to collect or review documentation beyond a subcontractor’s invoice, the OA is unable to substantiate the validity of those expenses reported by its contractors. When we shared our observations with the OA division chief, she asserted that the OA does not have adequate staff resources to review all supporting documentation for each subcontractor expense, so it has not enacted such a requirement. However, the OA is not precluded from requiring its contractors to provide it with the additional supporting documentation from subcontractors even if it does not have the resources to review all of this documentation. Merely requiring the contractors to provide that documentation to the OA would help ensure that the contractors collected the documentation from the subcontractors and reconciled the supporting amounts to the expenses reported on the subcontractors’ invoices. The division chief agreed that the OA could require its contractors to include this additional information when they submit their invoices to the OA and that OA staff could review some of these documents to spot check and ensure that the expenses are not fraudulent.

The OA Is Missing Opportunities to Improve Its Contract Management Processes

Through its audits of OA contractors, the compliance unit has become familiar with the OA’s contract oversight system and given the OA feedback to potentially improve its processes. Federal requirements indicate the OA should maintain effective internal controls that align with the Government Accountability Office’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (Green Book). According to the Green Book, entities should establish and operate activities to monitor their oversight systems and then remediate identified deficiencies on a timely basis. We reviewed the OA’s February 2024 administrative procedures and determined they do not include activities to monitor its oversight system like the Green Book describes. However, the compliance unit performs this function. The OA established the compliance unit in 2021 as an audit unit external from its program staff to audit its contractors.2 Figure 7 describes the compliance unit’s various functions, which include identifying potential improvements in the OA and communicating them to the OA via quarterly meetings. Although the compliance unit performs these functions in practice, neither its role in identifying potential improvements nor in communicating them via the quarterly meetings are required of it or are documented in OA’s policies. Nonetheless, in performing its work, the compliance unit has identified areas where the OA could improve its contract management practices and has taken the initiative to communicate these areas to the OA.

Figure 7

The Compliance Unit Assists the OA in Monitoring Its Contractors and Suggesting Improvements to Its Controls

Source: Interviews with compliance unit management, selected compliance unit audit reports, the compliance unit recommendation tracker spreadsheet, and quarterly compliance unit and OA meeting notes.

The compliance unit audits contractors at the OA’s request. Through the audit process, the compliance unit accomplishes two tasks: 1. The compliance unit finds issues with the OA’s contractors and develops recommendations for contractors to implement. 2. The compliance unit Identifies potential improvements in the OA’s oversight and develops suggestions for the OA to tighten its controls. To communicate consistently with the OA, the compliance unit holds quarterly meetings with the OA to discuss issues with contractors and suggestions about oversight for the OA to consider.

The OA has not consistently acted to address issues that the compliance unit identified while auditing OA contractors. In performing its work, the compliance unit identified five types of findings it had encountered with OA’s contractors, which the text box lists, and shared them with the OA. However, the OA has not acted to address the issue of inadequate documentation of subcontracted expenses. The compliance unit found that OA contractors were not retaining the documentation that the OA requires that they retain to verify the work performed by their subcontractors, and the compliance unit shared this issue with the OA in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. After learning about this problem, we would expect the OA to address this issue, for example by requiring contractors to submit the additional subcontractor documentation to the OA as part of the supporting documentation accompanying their own invoices, which would ensure that the contractors collect the documentation from the subcontractors. We specifically examined the Care Program, as it was the only OA program that received a published compliance unit finding indicating one of its contractors lacked sufficient backup documentation for subcontracted expenses. However, the Care Program section chief indicated that because its contracts do not presently require contractors to submit subcontractor backup documentation, the Care Program did not change its policies in response to this information.

Five Recurring Issues With Contractors

- Inadequate documentation for contracted expenses.

- Inadequate documentation of subcontracted expenses.

- Excessive indirect costs.

- Invoiced costs or services outside the budget period.

- Late annual financial audit reports.

Source: Quarterly meeting minutes from the compliance unit.

Additionally, the compliance unit has taken the initiative in these meetings to go beyond communicating the trends of its findings to further identify for the OA opportunities for it to make improvements to its overall contract management practices. Although the compliance unit’s policies do not require it to provide this feedback to the OA, over the course of its audits from July 2023 through April 2024, the compliance unit identified six items for the OA that vary in potential impact but all address opportunities for the OA to improve. The text box summarizes the items meant to tighten the OA’s controls and to improve its processes for administering grants.

Six Recommendations for Improvement

- Limit contractors’ spending on food.

- Ensure contractors track gift card distribution.

- Enforce inventory reporting requirements.

- Clarify program guidance on whether commingling gift cards is allowable.

- Perform internal reviews of templates to identify discrepancies.

- Revise budget guidance regarding accounting for salaries and fringe benefits.

Source: Quarterly meeting minutes and recommendation documents from the compliance unit.

Although the compliance unit identified these six items, it ultimately decided not to share two of them with the OA. In one case, as part of an audit of a Prevention Branch contractor, the compliance unit found an issue with how a contractor was tracking and distributing client incentive gift cards: the contractor was borrowing gift cards from another program. The compliance unit determined that the OA program guidance did not clearly allow or restrict the commingling of incentives between different programs and that the OA could clarify the guidance to either allow or restrict such an activity. The compliance unit also found that the OA should establish a process to perform internal reviews of templates to identify and correct discrepancies, because the compliance unit found a progress report template that the Prevention Branch provided its contractors that had two conflicting dates for when the contractors were required to submit them. According to the compliance unit chief, the unit ultimately determined that the issues did not represent trends and did not communicate them to the OA.

When we notified the Prevention Branch chief of the issues, he indicated that he would have preferred to learn about the issues at the time the compliance unit discovered them so he could have taken action to address them immediately. Because we brought the issues to his attention, the chief indicated that his branch updated its guidance to clarify that borrowing incentives from other programs is not allowed. Moreover, he indicated that the Prevention Branch had since implemented a management review as part of its document approval process to ensure that its templates do not include conflicting information. However, had this communication occurred when the issues were initially identified, the OA could have addressed them much sooner.

Public Health should establish policies that assign the compliance unit the role of providing the OA with program improvement feedback and that require the OA to act on that feedback. Because of the compliance unit’s role in auditing OA contractors, it is in an ideal position to evaluate the OA to provide it with program improvement feedback. By establishing this duty of the compliance unit in policy, Public Health would underscore the importance of this role to both the compliance unit and the OA. Given the OA’s reluctance to address the subcontractor supporting documentation issue and the compliance unit’s decision to not share all feedback to the OA that it desired to receive, Public Health should establish an oversight mechanism to prevent potential future inaction. For example, a review of the compliance unit trends and recommendations by the assistant deputy director of the Center for Infectious Disease would ensure that the compliance unit consistently shares all of the feedback to the OA that Public Health would like the OA to act on. Without a clearly defined policy for the OA to systematically receive and consider implementing the compliance unit’s feedback, Public Health is at risk that the OA will not learn about or resolve program management weaknesses that the compliance unit identifies, which will allow the weaknesses to continue. When we raised this issue with the OA and the compliance unit, both offices were amenable to the creation of an oversight mechanism to ensure accountability for the communication and resolution of OA oversight deficiencies.

Audit Objective 3 (summarized):

How does the OA determine the funding amounts it provides to jurisdictions and CBOs, and how does it measure program efficiency?

KEY POINTS

- The OA allocates funding appropriately and relies on relevant financial, demographic, and HIV surveillance data to determine contractor allocation amounts.

- The OA ensures that local health jurisdictions (jurisdictions) and community‑based organizations (CBOs) spend funding appropriately on services related to HIV and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). We reviewed 40 contracts and contract amendments that the OA issued from February 2021 through February 2024, and we found that the OA consistently ensured that its contracts with jurisdictions and CBOs contained services that were allowable based on the funding source.

- The OA does not have a standardized process to measure whether jurisdictions and CBOs use their allocations efficiently.

The OA allocates funding to jurisdictions and CBOs so they can provide HIV/AIDS‑related services. As Table B in Appendix B shows, the OA uses different methods to allocate funding depending on the program and whether it has a required allocation methodology. For example, state law requires the OA to use a competitive process to award funding to jurisdictions and CBOs to provide comprehensive HIV prevention and control activities for the most vulnerable and underserved individuals living with or at high risk for HIV infection, which it did for its Project Empowerment program. Specifically, the OA competitively awarded funding for the Project Empowerment program by reviewing and scoring applications from jurisdictions and CBOs based on their demonstrated expertise, history, and credibility at successfully engaging the most vulnerable and underserved individuals living with or at high risk for HIV infection. State law requires the OA to prioritize these elements when awarding funds under the program. Based on surveillance outcomes and population size, the OA determined that Black/African American and Latinx individuals and communities are the most underserved, and the OA considered applicants’ ability to prioritize those populations when reviewing applications for the Project Empowerment program. The 2019 Budget Act appropriated $4.5 million for HIV prevention and control activities, and in anticipation of recurring funding, the OA used those funds to support a series of three-year contracts. In its request for applications (RFA) and in its intent to award notification, the OA separated the series into three tracks of awards: one including five awards targeting Black/African American populations, one including five awards targeting Latinx populations, and one including five awards to hire staff for HIV prevention activities and to build capacity to serve these communities. As a part of the competitive bidding process for these awards, the OA scored the applicants based on their organizational and administrative capacity to fulfill program requirements and their demonstrated expertise, history, and credibility at working successfully in engaging with communities vulnerable to HIV infection. The OA scored each of the three applications that we reviewed three times. All nine reviews used the same scoring rubric that included scoring categories that directly applied to the funding source purpose and that provided scorers detailed guidance regarding how to evaluate each category. Further, for eight of the nine scores, the scorers included notes that justified their scoring.

As an alternative to using competitive bidding, the OA uses formulas to allocate funding throughout the State. For example, Table B in Appendix B shows that the OA uses a formula to allocate federal funding to subrecipients to support HIV care-related services under the Ryan White HIV Care Program (Ryan White Program). In consultation with a community advisory group, the OA developed this allocation formula, which considers a jurisdiction’s program expenditure data in the last three fiscal years, the number of people living with HIV within each jurisdiction in the five most recent years, and data related to the number of people living in poverty within a jurisdiction in the five most recent years. The OA weights the data to assign greater importance to actual expenditures with known values, and less importance to people living with HIV or AIDS and poverty data, which are estimates. In another example, the federal government, through the Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS (HOPWA) program, allocates funding to large metropolitan areas and to states, including California, based on the number of individuals living with HIV or AIDS as confirmed by the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To allocate funding to jurisdictions that include areas that do not receive direct funding from HUD, for example, not to large metropolitan areas, the OA uses a similar formula that considers the number of people living with HIV or AIDS in each jurisdiction. Moreover, the OA uses other factors—poverty data for each jurisdiction from the California Health Interview Survey and Fair Market Rent data from HUD—when allocating HOPWA funding to jurisdictions. After it has determined the funding allocation for a county or set of counties, the OA will issue an RFA to contract with jurisdictions or CBOs to provide HOPWA services in those counties. We found that the OA’s allocation formula for HOPWA funding is appropriate because it aligns with the federal allocation methodology, and because it incorporates other factors that align with the expected use of HOPWA funds—to assist with housing needs for low-income people living with AIDS.

In addition to allocating its funding in an appropriate manner, the OA must ensure that it and its contractors conduct HIV-related activities that adhere to the purpose and restrictions that the funding source of the activities establish. As we note in the Introduction, the OA uses funding from the State General Fund and several federal agencies and, depending on the source, the OA must limit the activities that its contractors may perform. For example, state law requires the OA to award funding to eligible entities to operate demonstration projects for innovative, evidence-informed approaches to improve the health and well-being of older people living with HIV, which it did for its Project Cornerstone program. Additionally, the Ryan White Program funding can only be used for activities under specific service categories, which are outlined in the program’s manual, such as home health care, AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) treatments, and oral health care. To address the requirements, the OA has implemented policies to ensure that its contracts include only activities that the funding sources allow.

To determine whether the OA adheres to its policies that ensure that its contracts include only allowable activities, we reviewed 40 contracts and contract amendments that the OA executed from February 2021 through February 2024. We found that in all 40 contracts and amendments, the OA ensured that contract activities were allowable based on the funding source. For example, the Care Program requires its contractors to submit a budget for their proposed activities, and the OA provides a budget template for the contractors to use for their submission. The OA prepopulates these budget templates with the list of the allowable service categories outlined in the manual of the Ryan White Program—the Care Program’s federal funding source—and the contractor must list its proposed activities under those service categories. After the OA reviews and approves the submitted budget, the OA emails a copy of the final budget and confirmation of approval to the contractor.

In addition to establishing policies that ensure that its contracts include only allowable activities, the OA developed policies that require its staff to monitor whether its contractors adhere to their contracted activities. Those policies require OA staff to review invoices to ensure that the amounts being billed are supported and align with the contracted activities. Further, depending on the program, OA staff complete various oversight activities to monitor contractors’ performance. For example, the OA collects and reviews progress reports for several of its programs including its Strategic Rapid Antiretroviral Treatment program and its Project Empowerment program, performs participant chart reviews for its Medi‑Cal Waiver program, and performs site visit reviews for its Care and HOPWA programs. For each of the 40 contracts that we reviewed, we evaluated whether the OA performed the appropriate monitoring according to the contract’s program and found that it did. For example, in a 2023 progress report for a jurisdiction’s contract for HIV surveillance and prevention work, the OA noted that the reported data showed that although HIV tests were occurring, the tests resulted in no positive cases. The OA did not express concern for the quality of testing but suggested that the contractor should assess local outreach and determine whether testing efforts should be redirected. The jurisdiction responded to the OA’s feedback noting it had made this consideration and planned to use epidemiology data to assess new testing locations. OA staff also conducted site visits to its grant recipients. We describe in Objective 4 the actions that the OA takes in response to its progress report reviews and site visits.

Although the OA allocates its funding to jurisdictions and CBOs in an appropriate manner, it does not have a standardized method to measure how efficiently its contractors use their allocations. According to the OA’s website, part of its mission is to assure high-quality preventive, early intervention, and care services that are appropriate, accessible, and cost effective. Additionally, Ryan White Program guidance directs recipients to follow the applicable federal cost principles when determining costs that may be charged to a Ryan White Program award. The federal cost principles state as a fundamental premise of their application that recipients of federal funding are responsible for employing organization and management techniques necessary to ensure the proper and efficient administration of their award. When we asked the Care Branch and Prevention Branch chiefs—the chiefs of the two OA branches that together manage six of the nine OA programs that were active in our review period and that did not use contracts that include predetermined services at predetermined rates—how their branches measure whether contractors use their allocations efficiently, they both indicated that their staff consider efficiency as a part of OA’s contract management process. Specifically, they described that their staff consider whether the activities included in the contracts fit the purpose of the funding for the contracts and that the budget amounts are reasonable for the work to be completed. The branch chiefs also indicated that their program staff would provide feedback to contractors to address any issues they identified before approving the contracts. The Prevention Branch chief also noted that one way his branch ensures that contractors use funds efficiently is by reviewing invoices, which allows staff to ensure that contractors adhere to the agreed-upon budget and activities in their contracts. However, although both branches consider efficient use of funds when monitoring their contracts, neither branch has a documented standardized process to measure efficiency. Consequently, it is unclear whether the OA effectively measures how efficiently its contractors use their funds.

The OA should take a systematic approach to evaluate whether its jurisdiction and CBO contractors use their allocations efficiently. Because the OA and its branches have not documented the reviews that the branch chiefs describe their staff currently perform, it is unclear whether the reviews are being completed, and the OA is not able to use summary data from the evaluations to guide its future decision making. Further, because the OA has not documented expectations for its staff to follow when performing their reviews, it is unclear whether the reviews are being performed in a uniform manner to allow the OA to ensure that it is collecting similar information from all contractors. By documenting clear expectations, like the example expectations the text box lists, for its staff to follow when they evaluate whether contractors plan to and have used funding efficiently, the OA will be able to use that information to guide its future decision making. For example, the OA might find that one contractor in a program uses a service technique that results in a lower cost of service per client that it could then recommend or require other contractors in the program to use as an efficiency best practice.

Example Efficiency Evaluation Expectations

- Evaluations must be documented.

- An evaluation to consider whether the budget amounts are reasonable must be performed before approving a contract budget.

- Each program must develop a definition of what is considered reasonable for its program staff to use.

- An evaluation to identify any activities that contractors exceeded their budget must be performed as part of contract close out.

Source: Auditor analysis.

When we asked the Care Branch chief whether it would be feasible to establish a documented process for staff to follow to measure contractors’ efficiency, the chief expressed concerns regarding the benefit of such work considering the variation of the Care Program from county to county. The Care Branch chief explained that counties provide different services, use different structures, and incorporate varying other funding sources into their operations. The chief stated that it would be difficult to define meaningful and useful efficiency measures, and that the issues the Care Program encounters are varied and sometimes do not occur more than once or twice. Nonetheless, Care Program contractors select the service categories that they will provide from a list of 23 categories, and the OA could compare efficiency outcomes between contractors that provide the same service categories. Further, regardless of the variation of condition from county to county, the OA could evaluate the extent that a contractor individually remains on budget and meets its proposed outcomes and compare among contractors how successful they are at achieving their proposed outcomes at planned costs. The OA could then evaluate why some contractors are more efficient than others and use the resulting information to improve its future program guidance. Despite regional variations, the HRSA, which administers the federal Ryan White Program, is still able to collect relevant HIV data from jurisdictions throughout the country, such as HIV viral suppression and client retention data, that it uses to create standardized performance benchmarks by dividing an observed outcome measure by the expected outcome measure. These benchmarks allow HRSA to compare a jurisdiction’s performance to national averages to gain an understanding of whether a jurisdiction is performing above or below expected results.

Audit Objective 4 (summarized):

Has the OA established a reasonable process for taking action when it finds jurisdictions and CBOs that are not using their allocations to adequately deliver services?

KEY POINTS

- The OA proactively monitors contractor performance to ensure that jurisdictions and CBOs adhere to their contracted statements of work and budgets by communicating guidance through feedback on progress reporting, delaying payment of invoices, and requiring corrective action plans in response to site visit evaluations.

- The OA takes corrective actions with its contractors based on the findings of the compliance unit, including having requested repayment from contractors as a result of 10 of the 43 compliance unit audit findings we reviewed for amounts the OA paid to the contractors for unallowable expenses.

- The OA has terminated only 13 of the 774 contracts that it entered from March 2019 through June 2024. In an effort to ensure a smooth transition for delivery of services, the OA terminated all of these contracts using its contract option that allowed it to terminate the contracts for any reason after providing a 30-day notice to the contractor. The underlying reasons for terminating these contracts varied, such as a contractor’s questionable performance and the OA’s decisions to minimize duplication of services provided among its contractors.

- The OA reasonably awarded a new contract to a contractor it had previously terminated through no fault of the contractor.

The OA Takes Corrective Actions With Contractors While Monitoring Their Ongoing Performance and Responding to Compliance Unit Audit Findings

The OA monitors its contractors by reviewing invoice documentation, monitoring progress reports, and conducting site visits. As part of our work to assess the effectiveness of OA’s monitoring and enforcement, we reviewed 22 OA invoice records. We found that the OA properly reviewed and paid 21 invoices but did not follow through to enforce its supporting documentation requirements for one invoice. In that case, OA staff identified that the contractor’s November 2023 invoice included an $11,707 expense related to food banks and home-delivered meals and provided backup documentation substantiating only $3,450 of the total expense. As a result, the OA disputed the invoice—taking its enforcement action to not pay the invoice without receiving further documentation—and requested the contractor to provide more documentation to support the additional expenses. The contractor attempted to send the relevant documentation to the OA several times, but the OA could not receive it because of technical difficulties related to the size of the files that the contractor was attempting to send to the OA. The OA nevertheless approved the invoice in January 2024 despite not being able to substantiate more than $8,000 of the invoiced amount. In doing so, the OA did not follow through with its enforcement process, which would have concluded with the OA not reimbursing the contractor for the unsupported amount. According to an email to the Care Branch chief requesting his approval to pay the invoice, the program did not want to delay payment of the invoice and stated that it would find a technical solution by the next quarter’s invoice submission to eventually obtain the supporting documentation.

We reviewed the next invoice submission to determine whether the OA was able to collect adequate supporting documentation for it and the missing supporting documentation from the previous quarter. According to the Care Section chief, who reports to the Care Branch chief, the OA was unable to collect the missing supporting documentation from the previous quarter because of staff turnover with the contractor and Public Health’s year-end close-out accounting deadlines. In addition, our review of the next invoice submission found that the OA did not collect supporting documentation for expenses totaling $17,416 within the following invoice period. These expenses included $500 of personnel expenses, such as payroll expenses, $7,885 in operating expenses, such as office supplies, and $9,031 in client services expenses, which included food and gas vouchers. Although the OA’s Care Program standards require subrecipients to submit time and attendance supporting documentation for personnel expenses and proof of purchase for all non‑personnel expenses, such as receipts for items or services purchased, the OA approved this invoice in June 2024 without such proof for the expenses we identified. In doing so, the OA approved an invoice submission that did not meet its program standards. According to the Care Section chief, the OA collected a summary expense report in lieu of adequate supporting documentation for this invoice because of staff turnover with the contractor and federal grant year-end close-out accounting deadlines.

Another form of monitoring that the OA’s staff perform is providing contractors with feedback to correct their approaches when the OA determines that the contractors are providing services in ways that do not meet its expectations. The OA’s policies require its staff to respond to contractors’ progress reports by providing feedback on their performance. We reviewed the most recent cycle of progress reporting for 20 of the 40 contracts that we evaluated for Objective 3, which the OA executed from February 2021 through February 2024, and found that the OA consistently provided the contractors with relevant feedback that frequently either affirmed their strong performance or that coached toward performance improvement. The OA provides feedback to contractors in three different categories that the text box summarizes. Of the 20 progress reports that we reviewed, at least one component of 18 contractors’ performances did not meet the OA’s expectations, and the OA provided each contractor with guidance for improvement. For example, after reviewing one contractor’s progress report, OA staff identified that the contractor did not record test results in the appropriate program outcomes tracking system and provided feedback to the contractor to begin doing so. This feedback is critical for the OA to provide to contractors to ensure that it collects complete and accurate data sets regarding its program outcomes.

The OA Responded to Progress Reports With Three Categories of Feedback

- Positive Feedback

- Provided to 20 of 20 contractors

- Requests for Additional Documentation

- Provided to 18 of 20 contractors

- Requests for Additional Detailed Responses

- Provided to 20 of 20 contractors

Source: OA contractor progress report reviews.

In addition to providing feedback in response to progress reports and invoice documentation, the OA conducts site visits of its HOPWA and Ryan White Program contractors and requires that they implement corrective action plans to address any resulting findings. As part of its site visits, the OA evaluates the contractor’s administrative policies and requirements, its fiscal management and oversight processes, and its delivery of services. When the OA reports a finding during a site visit, it informs the contractor and provides a recommendation. After the OA communicates its findings and recommendations to a HOPWA contractor, it requires that within 30 days, the contractor submit a corrective action plan to address the findings. Similarly, the OA requires that the contractor submit a corrective action plan for any deficiencies cited in monitoring reports or audits associated with a Ryan White Program, and the OA provides the deadline for that plan in its report to the contractor. In one Ryan White Program contractor’s site visit report we reviewed, the OA requested the contractor to submit its corrective action plan in approximately 30 days. HOPWA and Ryan White Program contractors must submit a corrective action plan for any deficiencies cited in the OA’s reports to their program adviser for approval and implement the plan. For example, as part of a February 2024 HOPWA program site visit, OA staff determined that the contractor did not obtain its required OA approval to allow individuals to receive short-term supportive housing for more than 60 days. The OA communicated the finding to the contractor and recommended that the contractor submit its policy for approval. The contractor then submitted the policy to the OA as part of its corrective action plan. In its response to the contractor, the OA noted that it reviewed and approved the policy and that the action corrected the finding. Having its contractors create plans to address and correct issues can help the OA ensure that they adequately provide key HIV/AIDS-related activities and services.

As another step in its enforcement process, the OA identifies the contractors that it would like the compliance unit to audit based on a risk assessment conducted by the OA. Although the compliance unit and the OA could improve their communication as discussed in Objective 2, the audit reports that the compliance unit provides the OA, which include findings and recommendations, allow the OA to take necessary corrective actions with the contractors to resolve the deficiencies that the compliance unit identified. Annually, the OA evaluates the risk associated with its contractors by considering factors such as the contractors’ numbers of subcontractors, billing issues the OA has encountered with the contractors, and timeliness of progress report submissions. The OA then communicates to the compliance unit its selection of contractors to be audited, and the compliance unit audits as many of the contractors as its resources for the year permit. For each audit, the compliance unit generally audits the previous year of performance of a contractor’s contract with the OA. Upon concluding the audit, the compliance unit creates a report of its findings and recommendations and provides a copy of the report to the contractor and to the OA. Examples of audit findings include contractors having submitted late progress reports, contractors having used inadequate accounting systems, and contractors lacking adequate support for expenses they received payment for from the OA. The compliance unit also recommends how the contractors should resolve any findings, including recommending recompensation payments to the OA when the contractors received payment for unsupported expenses.

The OA’s procedures for following up on compliance unit findings include establishing a 60-day timeline for contractors to act on findings and having staff follow up at the next site visit to ensure that the corrective action plan has been fully implemented. Among the 22 audits the compliance unit completed from December 2021 through January 2025, the compliance unit reported 43 findings. We evaluated whether the OA followed its policies to establish corrective action plans to address 10 of these 43 findings and whether it followed through to ensure that contractors completed those plans. We determined that the OA has taken action to verify that its contractors implement corrective actions to resolve their findings. For example, when the compliance unit noted a Care Program contractor was repeatedly submitting late progress reports, the Care Program adviser ensured that at the following site visit, the contractor was submitting progress reports in a timely manner. Additionally, we found that the OA recovered $119,000 through recompensation payments for seven compliance unit findings that involved invoices that either included expense amounts that exceeded actual costs, expense amounts from outside the invoice period, or expense amounts that the contractor could not support with documentation.

The OA Rarely Terminates Contracts and Is Generally Not Restricted From Contracting With a Contractor It Has Previously Terminated

From March 2019 through June 2024, the OA entered into 774 contracts and terminated only 13, using its contract term to terminate without cause after providing a 30-day notice for each. We used the Public Health Contracting and Purchasing System (CAPS), managed by its Program Support division, to determine the number of contracts that the OA had entered into from March 2019 through June 2024. We also attempted to use the CAPS to identify the number of contracts that the OA terminated. However, the CAPS does not track contracts according to whether they were terminated. We then requested a list of terminated contracts from the OA Support Branch chief. Because the OA did not centrally track the contracts that it had terminated, the OA Support Branch chief worked with the other branch chiefs to develop a list of the contracts that each branch had terminated since March 2019. Although the Budget Acts passed from 2018 through 2024 have exempted the contracts or grants administered by the OA from the Public Contract Code and from approval by the Department of General Services prior to execution, the special terms and conditions (terms) included in 12 of the OA’s terminated contracts specify that Public Health reserves the right to terminate an agreement immediately for cause, defined as the contractor’s failure to meet the terms or responsibilities of the agreement. The terms in these terminated contracts also allow Public Health to terminate a contract without cause but requires it to provide the contractor with advance written notice 30 days before doing so. One of the terminated contracts was with the University of California, San Francisco that included the University Terms and Conditions, which required the OA to provide the university with the advanced 30-day notice to terminate the contract with or without cause. We determined that all of the contracts that the OA ended were terminated without cause and that the OA appropriately provided each contractor the required 30-day advanced written notice.

The OA’s reasons for terminating these contracts varied. For example, it terminated three contracts with a single contractor because the contractor went out of business. The OA indicated that it terminated contracts with other vendors to consolidate the services provided for in those contracts under other providers in those counties. For these contracts, the OA’s goal was to minimize duplication of services and the administrative costs from multiple agreements and to provide more streamlined coordination of care to the impacted clients. In contrast, the OA terminated one contract we reviewed because of the contractor’s deficient performance. Specifically, according to the OA Support Branch chief, the OA had identified deficiencies in that contractor’s performance during a site visit and then terminated the contract after the contractor refused to provide the OA adequate supporting documentation for its invoices. However, the OA still chose to terminate the contract without cause as its contract term allowed. The OA’s division chief stated that, based on recommendations from Public Health’s Office of Legal Services (OLS), the OA determined that terminating its contracts without cause likely resulted in a smoother service delivery transition.

We further questioned the OLS to better understand its reasoning for using this form of contract termination. The assistant chief counsel of OLS noted that terminating a contract without cause provides Public Health more flexibility than terminating with cause might provide. She indicated that terminating with cause may result in protracted contract disputes and increased potential for litigation, while terminating without cause allows Public Health to more effectively wrap up services while maintaining a continued linkage to care for the recipients of those services. She stated that terminations without cause allow for an easier transition to a new service provider. Consequently, the OA’s ability to provide consistent and seamless delivery of services to its clients is less likely to be impacted when it terminates contracts experiencing performance issues without cause as opposed to with cause.

The OA awarded a new contract to a contractor it had previously terminated through no fault of the contractor. When OA program staff evaluate contractors for approval, the OA Support Branch chief explained that staff ensure that the contractors are capable of providing the services for which the OA is awarding the contract and take into account whether the OA previously terminated a contract with that contractor. Among the 13 terminated contracts that we reviewed, we identified one instance in which the OA awarded a new contract to a contractor after having previously terminated a contract with that contractor. Specifically, the OA terminated without cause the prior contract to administer subcontracts on behalf of the OA for various HIV prevention services. In the OA’s 30-day notice to the contractor, the OA stated that it would directly administer the funds. In February 2024—two months after it terminated the prior contract—the OA awarded that previous contractor a new contract for services to administer the California Overdose Prevention and Harm Reduction Initiative, funded in the Budget Act for fiscal year 2023–24. In this instance, the OA terminated the prior contract for reasons that were not related to the contractor’s ability to administer a program. Under these circumstances, we find it reasonable that the OA awarded the new contract to the contractor that the OA had previously terminated.

The OA should establish a policy to centrally track the contracts that its branches terminate. According to the Support Branch chief, the OA would not award a contract to a vendor that it had previously terminated a contract with if the previous termination demonstrated that the contractor was not capable of providing the new contract services. However, without having maintained a central list of contracts that had been terminated among all the OA branches prior to our request, it is unclear how a contract reviewer would have been aware of concerning issues that may have occurred in another OA branch that was using the same contractor. Consequently, the OA should maintain its newly developed list of terminated contracts and add any future terminated contracts, so that its staff can be aware of them when making contracting decisions. The Support Branch chief explained that the OA is planning to maintain its list for this purpose.

Audit Objective 5 (summarized):

Does the OA use funds for outreach and education appropriately and effectively?

KEY POINTS

- The OA’s Prevention Branch funds outreach and education efforts through contracts with CBOs and participating jurisdictions aimed at increasing awareness and engagement among vulnerable communities, such as LGBTQ+ individuals and people of color, and monitors and evaluates the success of these programs.

- The OA facilitates communication with jurisdictions and CBOs through a monthly virtual call and a newsletter providing program updates and relevant health information to help raise awareness of available programs and services that benefit the public and CBOs.

CBOs and Participating Jurisdictions Perform Various Types of Outreach and Education Activities

Our review of contracts between the OA’s Prevention Branch and participating jurisdictions and CBOs found that the contracts include outreach and education activities designed to maximize impact in vulnerable communities. For example, the OA states in its Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) RFA—a document outlining the requirements for CBOs and jurisdictions when they receive funding for the Prevention Branch program—that providers must engage with priority populations. PrEP is a medication regimen used to prevent HIV infection among people who are at high risk of exposure. Priority populations include non-white homosexual men, transmen, and non-binary individuals, among others. These outreach and education efforts aim to increase the number of people taking medication pre- and post-HIV diagnosis, and to provide individuals with comprehensive and sex-positive sexual health education. The Prevention Branch allocated approximately $4 million for its programs across 20 different contracts in fiscal year 2023–24.

Our review of 19 contracts the Prevention Branch entered into from February 2021 through February 2024 found that the OA consistently requires CBOs to conduct outreach and education activities, such as conducting social media outreach or providing pharmacies with educational materials. Additionally, we found that the OA followed up with the CBOs through progress reports to ensure that they have conducted outreach and education activities. In these reports, the OA monitors and evaluates the success of outreach efforts and asks clarifying questions to better understand the reported efforts and identify successful strategies. These reports represent a consistent effort by the OA to ensure that CBOs conduct outreach and education.