2024-106 Highlands Community Charter and Technical Schools

Lax Oversight Allowed Highlands to Inappropriately Receive More Than $180 Million in K–12 Funding

Published: June 24, 2025Report Number: 2024-106

June 24, 2025

2024-106

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of Highlands Community Charter and Technical Schools (Highlands) and Twin Rivers Unified School District (Twin Rivers). Our assessment focused on whether Highlands complied with state law and other applicable requirements and the sufficiency of Twin Rivers’ oversight of Highlands, and the following report details the audit’s findings and conclusions. In general, we determined that Highlands received more than $180 million in K–12 funds for which it was not eligible, it engaged in wasteful spending, and it assigned teachers to classes for which they did not hold appropriate credentials. Additionally, we found that Twin Rivers and other oversight agencies did not provide adequate oversight of Highlands.

Highlands, which serves adult students but receives K–12 funding as a result of its partnership with a Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) organization, collected millions of dollars in K–12 funding for its classroom-based school despite not meeting key conditions of funding. Further, Highlands received more than an estimated $5 million in overpayments by not complying with state law in calculating its average daily attendance. We also found that Highlands engaged in several questionable financial transactions, including some that violated legal prohibitions against gifts of public funds and conflicts of interest. My office found that Highlands hired and promoted unqualified individuals, and often assigned teachers to classes for which they did not hold appropriate credentials. Highlands also avoided transparency and accountability for its poor student outcomes by not complying with certain reporting requirements and not conducting standardized testing.

In addition, we found that Twin Rivers, the Sacramento County Office of Education, and the California Department of Education took insufficient action to ensure that Highlands addressed findings from a 2018 audit by the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team that reported multiple serious and deficient internal practices at Highlands. In addition, Twin Rivers conducted only minimal annual oversight of Highlands, and instead relied heavily on annual audits that we found had inaccuracies. If Twin Rivers had conducted more thorough oversight, it could have identified some of the violations we identified as part of our audit and taken action to address them earlier.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CAASPP | California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress |

| CalSAAS | California Statewide Assignment Accountability System |

| CAST | California Science Test |

| CICA | California Innovative Career Academy |

| CTC | Commission on Teacher Credentialing |

| CTE | Career technical education |

| ESL | English as a Second Language |

| FCMAT | Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team |

| GAO | Government Accountability Office |

| HCCS | Highlands Community Charter School |

| LCAP | Local Control Accountability Plan |

| LCFF | Local Control Funding Formula |

| LEA | Local educational agency |

| SETA | Sacramento Employment Training Agency |

| TANF | Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

| WIOA | Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

Highlands Community Charter and Technical Schools (Highlands) is a nonprofit corporation operating two charter schools in California. Highlands Community Charter School (HCCS), a classroom‑based school, opened in 2014, and California Innovative Career Academy (CICA), an independent study school, opened in 2019. Twin Rivers Unified School District (Twin Rivers) authorized the charters for both schools. Both schools serve adult students 22 years or older but receive state K–12 funding through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) as a result of Highlands’ partnership with a Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) organization. WIOA is federal legislation designed to help job seekers access employment, education, training, and supportive services, and state law allows charter schools providing instruction in exclusive partnership with a WIOA organization to receive K–12 funding for adult students. As of Fall 2024, Highlands had more than 700 employees serving more than 13,700 students across more than 50 locations throughout the State. Highlands is subject to oversight from Twin Rivers and through its annual financial and compliance audits, which are audits conducted by a Certified Public Accountant. Highlands has experienced dramatic enrollment and revenue growth since 2019, but audits and media investigations have reported significant operational issues, including attendance discrepancies, conflicts of interest, and excessive spending.

Highlands Received More Than $180 Million in K–12 Funds for Which It Was Not Eligible

Highlands collected millions of dollars in K–12 funding for its classroom‑based school despite not meeting conditions of funding relating to its mode of instruction. By not offering the required amount of instruction at the schoolsite, requiring students to attend class at the schoolsite for the minimum amount of time required by law, or meeting requirements for nonclassroom‑based instruction, HCCS was not eligible to receive the $177 million in K–12 funding it received in fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24. Further, Highlands received more than an estimated $5 million in overpayments, of which $3.5 million is in addition to the $177 million in disallowed funding, by not complying with state law in calculating its average daily attendance (ADA). Highlands also lacked verifiable documentation for the attendance it recorded for both HCCS and CICA, which calls into question whether the attendance Highlands reported for both schools is accurate.

Highlands Has Engaged in Wasteful Spending and Inappropriate Hiring Practices

Highlands lacked sufficient controls over its spending to prevent waste of the public funding it receives. We found that Highlands engaged in several questionable transactions, including some that violated legal prohibitions against gifts of public funds and conflicts of interest, such as entering into a contract for mentor services with the spouse of a Highlands director. Further, we found that Highlands impeded public transparency by not seeking board approval for some contracts and purchases that exceeded the cost thresholds outlined in the few policies it had. Highlands also lacked clear hiring and compensation policies. Highlands hired and promoted unqualified individuals and had inadequate protections against nepotism. Its lack of standardized procedures for assigning salaries and bonuses also leaves it vulnerable to potential claims of favoritism or unfairness.

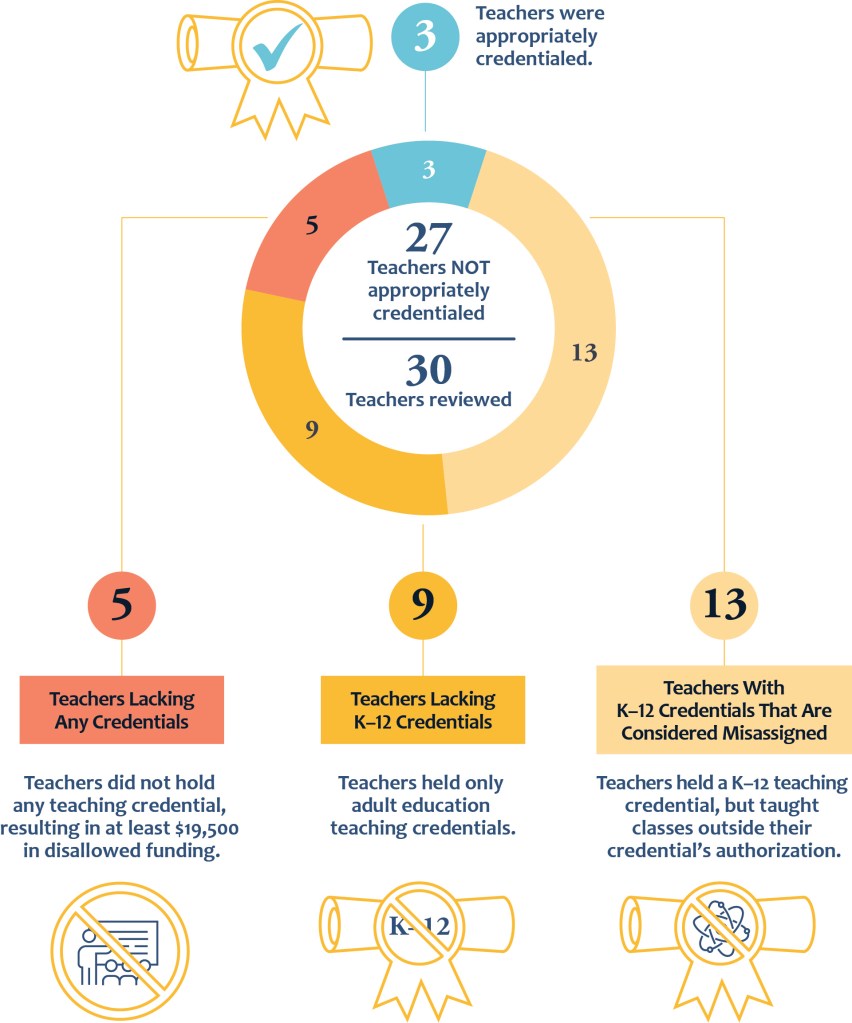

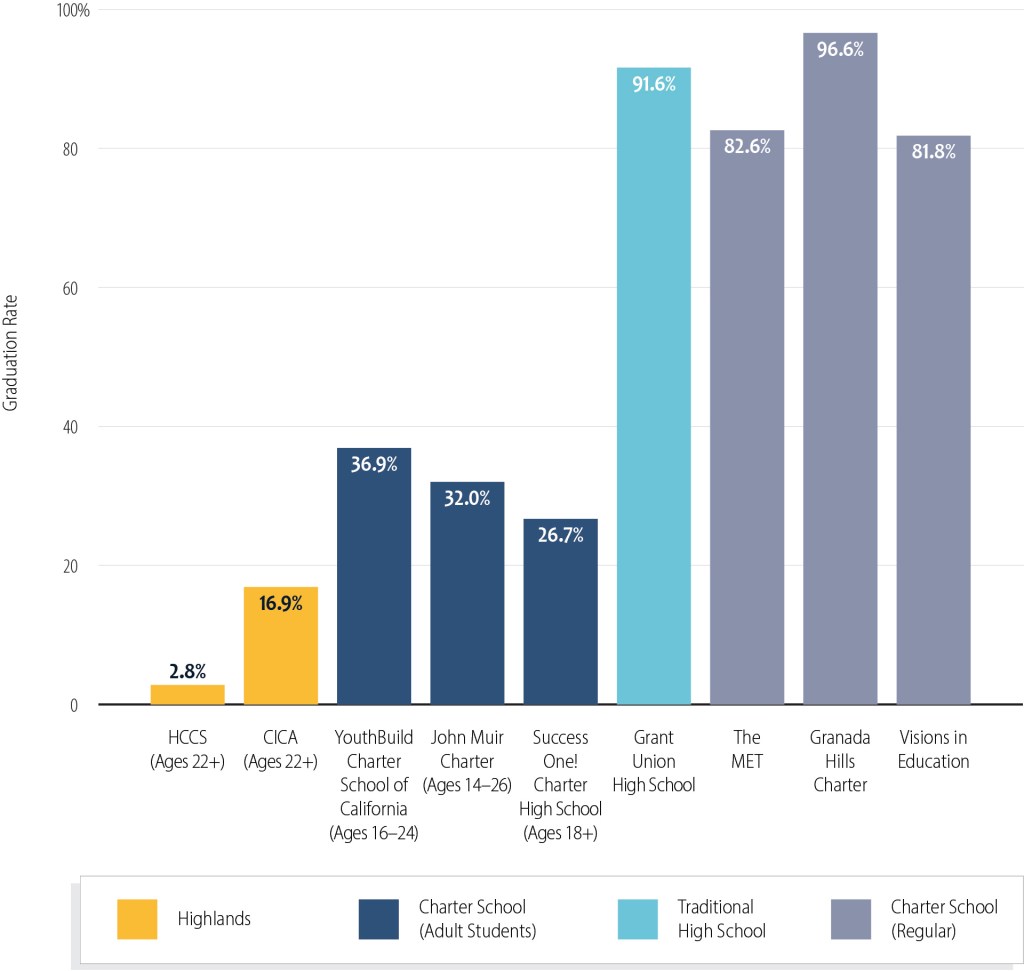

Unqualified Teachers and Large Student Enrollment May Contribute to Poor Student Outcomes at Highlands’ Schools

The majority of Highlands teachers we tested did not hold appropriate credentials for the classes they taught, and some lacked any credentials at the times when they were teaching classes. The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) in fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24 reported that Highlands repeatedly and increasingly assigned teachers to classes for which they did not hold appropriate credentials. Further, Highlands exceeded the allowable student‑to‑teacher ratio for CICA, its independent study school. For its classroom‑based school, HCCS, Highlands had a student‑to‑teacher ratio of 51:1. Although there is no maximum class size in state law for grades 9 through 12, this ratio far exceeded that of neighboring schools and school districts. These issues may have contributed to Highlands’ poor student outcomes. According to the California Department of Education’s (CDE) graduation rate data, HCCS had a graduation rate of 2.8 percent in fiscal year 2023–24, and CICA’s graduation rate was 16.9 percent in the same year. CDE determined that Highlands’ schools’ graduation rates were so low that they dropped the overall statewide graduation rate for the 2023–24 school year by more than half of a percentage point, from 87 percent to 86.4 percent. Because Highlands is operating in partnership with a WIOA organization, state law exempts it from the requirement that charter schools are eligible to receive K-12 funding for students over 19 years old only if the student is making satisfactory progress toward the completion of a high school diploma. Further, by not complying with certain reporting requirements and not conducting standardized testing, Highlands avoided transparency and accountability for its student outcomes.

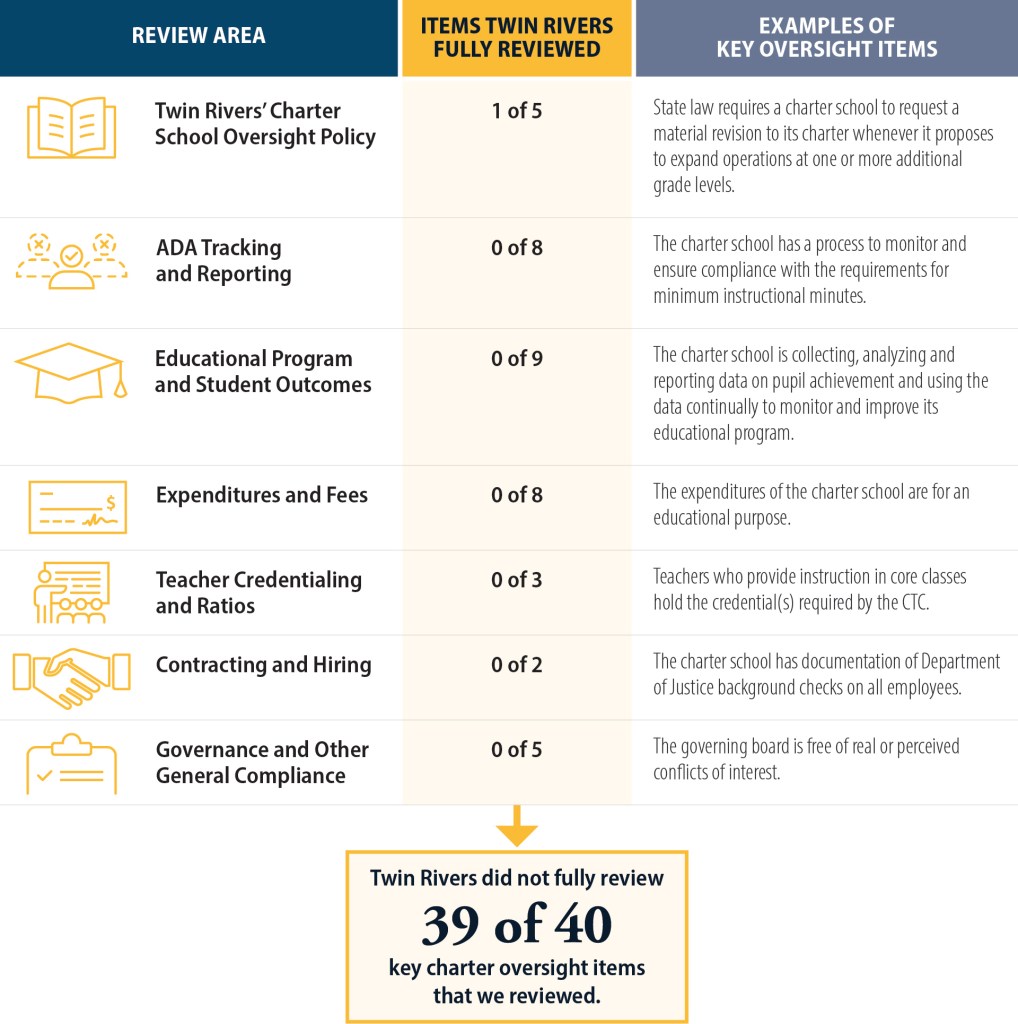

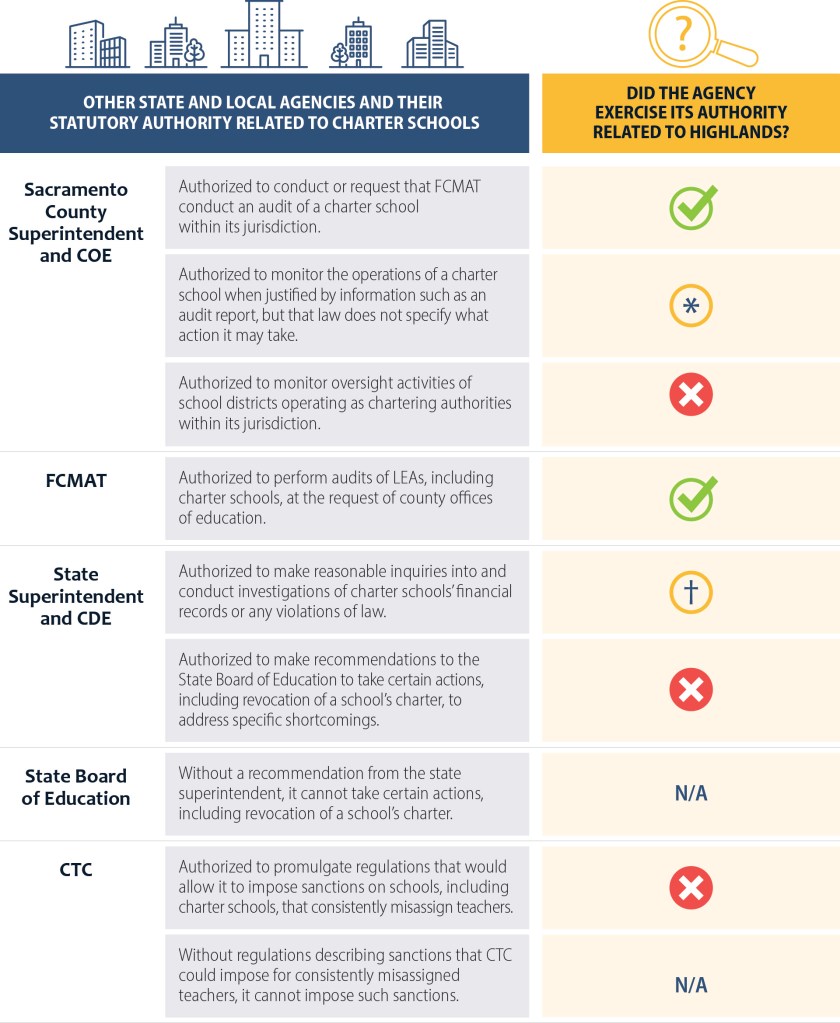

Twin Rivers and Other Educational Entities Did Not Provide Adequate Oversight of Highlands

At the request of the Sacramento County Office of Education (Sacramento COE), the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT) performed an audit that reported multiple serious and deficient internal practices at Highlands in 2018. However, the Sacramento COE took minimal actions to ensure that Highlands and Twin Rivers addressed the findings, and CDE did not fully respond to Sacramento COE’s request to address the FCMAT findings. Further, Twin Rivers did not require Highlands to resolve the FCMAT findings and other deficiencies in CICA’s charter petition before recommending the district’s board conditionally approve the petition in 2019. In addition, Twin Rivers conducted only minimal oversight of Highlands and instead relied heavily on annual audits that we found had inaccuracies. If Twin Rivers had conducted more thorough oversight, it could have identified some of the violations we identified as part of our audit and taken action to address them earlier. Twin Rivers collected $12.9 million in oversight and facility fees from Highlands from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, but because the district does not track the costs of its oversight, it may have been entitled to less than it received.

To address these findings, we recommend that the Legislature establish maximum allowable student‑to‑teacher ratios for adult serving classroom‑based charter schools and require charter schools that provide instruction to adults in exclusive partnership with a WIOA organization be subject to the requirement that its students make satisfactory progress toward a high school diploma. We include a summary of legislative recommendations in Appendix A. We also recommend that Highlands align its attendance policies and reporting practices with the conditions of receiving K–12 funding and other requirements in state law. We further recommend that Highlands implement policies to spend public funds appropriately, prevent favoritism in its hiring practices, and ensure that its teachers have proper credentials.

To address the lax oversight on the part of responsible state and local agencies, we recommend that Twin Rivers implement policies and procedures to conduct charter school oversight that better aligns with state guidance and best practices, and to outline specific steps for investigating and resolving potential violations of state law or the charters, including issuing written notices of violation that could lead to revocation of a school’s charter if not resolved. Further, we recommend that if CDE determines that Highlands has failed to significantly address the audit findings in this report or others, or that Highlands violated state law, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction should make a recommendation to the State Board of Education to take appropriate action, up to and including revoking Highlands’ charters.

Agency Comments

Highlands and Sacramento COE generally agreed with our recommendations, but provided responses that disagreed with some of the report’s findings and conclusions. Twin Rivers generally questioned whether our recommendations were legally enforceable. CDE and CTC both generally agreed with our recommendations.

Introduction

Background

In 1992, California lawmakers enacted legislation to establish charter schools as part of its public education system, making it the second state to do so. As of May 2024, there were 1,283 charter schools and seven all‑charter school districts in California. California law prohibits charter schools from charging tuition. According to CDE, charter schools may include any combination of grades from transitional kindergarten through grade 12 (K–12).

The legislative intent of the Charter Schools Act of 1992 is to provide opportunities to establish charter schools that operate independently from the existing school district structure as a method to accomplish certain goals. These goals include providing competition within the public school system, encouraging the use of different and innovative teaching methods, and creating new professional opportunities for teachers.

A person starting a charter school begins the process by circulating a petition for the establishment of the charter school. The petition is then submitted to the governing board of the school district in which the charter school is to be established. The charter school’s petition must lay out its proposed governance structure, the qualifications to be met by employees, educational goals for students and how those goals will be measured, and other requirements. The school district governing board then reviews the charter, holds a public hearing regarding the charter, and decides whether to approve or deny the charter.1 Charter schools are largely exempt from the state statutes and regulations governing school districts.

Founding of Highlands

Highlands is a California nonprofit public benefit corporation that operates two K–12 charter schools, each with multiple locations, that provide instruction to adults 22 years or older who do not have a U.S. high school diploma. Twin Rivers authorized the charters for both schools and bears primary responsibility for their oversight. Highlands opened its first K–12 charter school—HCCS—in August 2014 to provide classroom‑based instruction. Highlands opened its second K–12 charter school—CICA—in August 2019, which provides independent study‑based instruction. As Figure 1 shows, Highlands has seen dramatic growth in both its enrollment and revenue from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25. As of Fall 2024, Highlands had more than 700 employees at more than 50 locations throughout the State serving—as of February 2025—more than 13,700 students.2 HCCS and CICA are the 1st and 37th largest schools, respectively, in the State by enrollment and combined represent nearly 30 percent of the enrollment in Twin Rivers.

Figure 1

Highlands’ Reported Enrollment and Revenue Increased Significantly From Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2024–25

Source: Highlands’ financial statements, student data, and budget projections.

Figure 1 is a graph that shows Highlands’ reported enrollment and reported revenue for fiscal years 2019-20 through 2042-25. The graph has a yellow line that angles upwards to the right on top of six blue bars that increase in height from left to right. On the left, the vertical axis goes by increments of 5,000, starting at zero and ending at 25,000. On the right, the vertical axis goes by increments of $40, starting at $0 and ending at $200. A rectangle in the same color blue as the bars on the graph is above the left vertical axis and says “Enrollment (HCCS and CICA)”. A line with a point in the middle that is the same color yellow as the line on the graph is above the right vertical axis and is below the words “Revenue (in millions)”. The horizontal axis lists fiscal years 2019-20, 2020-21, 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-24 unaudited, and 2024-25 budgeted. The bar over 2019-20 is labeled 3,505 and the line has a point over 2019-20 that is labeled $29. The bar over 2020-21 is labeled 3,588 and the line has a point over 2020-21 that is labeled $43 million. The bar over 2021-22 is labeled 4,531 and the line has a point over 2021-22 that is labeled $66 million. The bar over 2022-23 is labeled 8,951 and the line has a point over 2022-23 that is labeled $137 million. The bar over 2023-24 Unaudited is labeled 12,249 and the line has a point over 2023-24 that is labeled $168 million. The bar over 2024-25 Budgeted is labeled 15,429 and the line has a point over 2024-25 budgeted that is labeled $195 million.

Highlands emphasizes that it serves a diverse and underserved population by providing access to education and employment to students from a wide range of age, ethnic, cultural, and language backgrounds, including students from 95 countries speaking 69 languages. Highlands provides educational programs that address three different areas of learning. It offers an International High School program where students can earn credits toward a high school diploma while improving their English comprehension and communication skills. Second, it offers a High School program, which allows students to earn credits toward their high school diploma while continuing to strengthen their communication skills in academic and workplace settings. Highlands also offers Career Technical Education (CTE) courses in conjunction with its high school program, which provide opportunities for students to develop workforce skills, obtain certifications, and earn elective credits toward a high school diploma.

Highlands’ Funding

Charter schools in California receive state funding through California’s LCFF, which is based primarily on a school’s ADA in each grade span up to and including grade 12. LCFF is the primary mechanism for distributing state educational funding to K–12 schools. As such, we refer to LCFF funding throughout this report as K–12 funding. This method of funding K–12 schools differs from the state’s primary method of funding adult education, which allocates funding to local adult education consortiums according to measures of need and effectiveness, as well as the amount of prior year funding. K–12 funding accounted for about 85 percent of Highlands’ revenues in fiscal year 2022–23, or about $117 million. Other state and local revenues accounted for about 14 percent of Highlands’ revenues in fiscal year 2022–23, or about $20 million. Highlands also received federal revenue of about $1 million, most of which came from an adult education grant from WIOA—a federal law that we describe further in the next section—that accounted for less than one percent of its fiscal year 2022–23 revenues. As Figure 2 shows, there are key differences between adult education and K–12 education in California.

Figure 2

Key Differences Between K–12 and Adult Education in California

Source: State law, CDE publications, a Legislative Analyst’s Office report, and California Community Colleges Data Vista—California Adult Education Program Score Card.

* A participant is defined as an individual who receives 12 or more instructional contact hours at any institution within the academic or program year.

Figure 2 is a figure comparing the key differences between K-12 and the adult education program in California. The figure is comprised of two columns, with labels on the left and across the top. The labels on the left are “Population Served,” “Attendance Requirements,” “Fees,” “How State Funding is Determined,” and “Funding.” At the top of the left-hand column is the label “K-12.” At the top of the right-hand column is the label “California Adult Education Program.” There is an illustration of four children above the “K-12” label and an illustration of four adults above the “California Adult Education Program” label. Under “K-12,” in line with the “Population Served” label, is text that reads “Generally children aged 5-19 who have not yet graduated from high school.” Under this text, in italics, is the statement “Various exemptions to the age limit exist.” Under “California Adult Education Program,” in line with the “Population Served” label, is text that reads “Generally, adults aged 18 or older.” Under “K-12,” in line with the “Attendance Requirements” label,” is text that reads “California compulsory education law generally requires children between 6 and 18 years of age to attend school. Truant students may face disciplinary or legal consequences.” Under “California Adult Education Program,” in line with the “Attendance Requirements” label, is text that reads “State law does not compel attendance.” Under “K-12,” in line with the “Fees” label, is text that reads “Public schools, including charter schools, may not charge fees for educational activities.” Under “California Adult Education Program,” in line with the “Fees” label, is text that reads “Adult schools may charge fees, except for classes such as English, citizenship, or high school credit classes when taken by someone without a high school diploma or equivalent.” Under “K-12,” in line with the “How State Funding is Determined” label, is text that reads “Generally driven by average daily attendance.” Under “California Adult Education Program,” in line with the “How State Funding is Determined” label, is text that reads “California Adult Education Program (CAEP) funding is not based on attendance.” Under “K-12,” in line with the “Funding” label, is text that reads “State K-12 (LCFF) Funding for Fiscal Year 2023-24: Estimated average of $14,750 per student statewide.” Under “California Adult Education Program,” in line with the “Funding” label, is text that reads “Adult school funding is not linked to student attendance and adult schools have widely different per-student funding rates.” Underneath that statement is a breakdown of this funding amount for several school districts. This breakdown starts with the statement “State CAEP Funding amounts provided per participant at a selection of school districts *:” Underneath this statement are three examples, which read “Los Angeles Unified School District – Adult Education $2,205 per participant,” “Montebello Unified School District – Adult Education $3,893 per participant,” and “Garden Grove Unified School District – Adult Education $1,017 per participant.”

Highlands’ WIOA Agreement with the Sacramento Employment Training Agency

Despite receiving K–12 funds, Highlands is exempted from key legal requirements that apply to K–12 schools by virtue of its agreement with a WIOA agency. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, WIOA is legislation designed to strengthen and improve the nation’s public workforce system by helping job seekers access employment, education, training, and supportive services to succeed in the labor market. Highlands has an agreement with the Sacramento Employment Training Agency (SETA), the organization responsible for the oversight and administration of WIOA in the Sacramento area. Under this agreement, Highlands must enroll only students who are eligible WIOA participants.

State law typically only allows charter schools to receive K–12 funding for a student over the age of 19 if the student has been continuously enrolled in public school and is making satisfactory progress toward the completion of a high school diploma. However, state law exempts from these requirements charter schools that provide instruction exclusively in partnership with a WIOA organization. Consequently, that exemption allows Highlands to receive K–12 funding for adult students regardless of whether they have been continuously enrolled or are making satisfactory progress toward a high school diploma. State law also generally requires charter schools to be located within the geographic boundaries of the authorizing school district, but another exemption in state law for charter schools that provide instruction exclusively in partnership with a WIOA organization allows Highlands to open and operate schools across the State.

Oversight of Highlands

Oversight of California’s public education system involves multiple levels, including various agencies at the state, county, and local levels. The level of oversight and the associated responsibilities for these agencies vary, as we show in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Entities with Responsibilities Related to Overseeing Education and Highlands

Source: California law, CTC publications, Sacramento COE website, Twin Rivers board minutes, CDE documentation, Highlands documentation, and other documents.

Figure 3 shows the entities with responsibilities related to overseeing education and Highlands. At the top are three boxes spaced equally along one row that are dark blue on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. The first has the label “California Department of Education” on the dark blue part of the box and the description “At the direction of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, responsible for enforcing education law and regulations, and allocating funding for local educational agencies” on the white part of the box. The second has the label “State Board of Education” on the dark blue part of the box and the description “The State Board of Education is the policy-making body for California’s K-12 public education system” on the white part of the box. The third has the label “California Commission on Teacher Credentialing” on the dark blue part of the box and the description “Provides licensing, credentialing, enforcement, and discipline to ensure that educators meet professional standards for public K-12 schools in California” on the white part of the box. The next box down is below “State Board of Education” and is a lighter blue on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. It has the label “Sacramento County Office of Education” on the lighter blue part of the box and the description “Provides technical assistance, curriculum and instructional support, staff development, financial advice, and oversight to Sacramento County school districts and charter schools” on the white part of the box. To the left of this box, beneath “California Department of Education,” but lower on the page than “Sacramento County Office of Education,” is a box that is sky-blue on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. It has the label “Fiscal Crisis Management and Assistance Team” on the sky-blue part of the box and the description “Provides local educational agencies with management assistance and training to identify, prevent, and resolve financial, operational, and data management challenges. FCMAT provides management assistance at the request of any school district, charter school, or county office of education” on the white part of the box. Below the “California Commission on Teacher Credentialing” box, to the right of the “Sacramento County Office of Education” box but a bit lower on the page, is a box that is pink on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. It has the label “Sacramento Employment and Training Agency” on the pink part of the box and the description “The Local Workforce Investment Board for Sacramento County, which partners with Highlands to provide services to WIOA recipients. This agreement allows Highlands to receive K-12 funding for adults” on the white part of the box. Below the “Sacramento County office of Education” box is a box that is gray on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. It has the label “Twin Rivers Unified School District” on the gray part of the box and the description “Oversees charter schools that it authorizes. Can approve, renew, or revoke schools’ charter petitions” on the white part of the box.” Below this box is a box that is gold on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. It has the label “Highlands Community Charter and Technical Schools” on the gold part of the box and the description “A nonprofit organization, governed by its board of directors, that manages and operates Highlands Community Charter School and California Innovative Career Academy” on the white part of the box. Below this box are two boxes equally low on the page that are both paler gold on the top third and white on the bottom two thirds. The left of these two boxes has the label “Highlands Community Charter School (HCCS)” on the pale gold part of the box and then a two-part description on the white part of the box. The top of the description reads “Classroom-based Instruction” and the bottom reads “Offers California residents age 22 or older without a U.S. high school diploma the opportunity to obtain a high school diploma and career technical education.” The right of these two boxes has the label “California Innovative Career Academy (CICA)” on the pale gold part of the box and then a two-part description on the white part of the box. The top of the description reads “Nonclassroom-based Instruction” and the bottom reads “Offers California residents age 22 or older without a U.S. high school diploma the opportunity to obtain a high school diploma and career technical education.”

To promote accountability over public educational funding and encourage sound fiscal management practices, California law requires local educational agencies, including charter schools, to undergo an annual financial and compliance audit performed by a Certified Public Accountant in accordance with government auditing standards. State law requires the State Controller’s Office to propose, in consultation with the Department of Finance, CDE, and representatives of specified organizations, an audit guide that describes procedures for conducting these audits. The State Controller’s Office then submits the proposed audit guide to the Education Audit Appeals Panel for review, possible amendment, and adoption through the rulemaking process. Once adopted, the Guide for Annual Audits of K–12 Local Educational Agencies and State Compliance Reporting (K–12 audit guide) forms the basis for the annual audits that Highlands and all charter schools undergo.

In December 2016, the Sacramento COE entered into an agreement with FCMAT to conduct an extraordinary audit of Highlands to determine if fraud, misappropriation of funds, or other illegal fiscal activities may have occurred. FCMAT is an independent and external state agency created in 1991, and its primary mission is to assist California’s local educational agencies to identify, prevent, and resolve financial, human resources, and data management challenges. FCMAT published its audit in May 2018 in which it identified multiple serious issues, including attendance calculation irregularities, lack of support for student outcomes, conflicts of interest, and allegations of sexual harassment. In the conclusion of its report, FCMAT stated that these findings should be of great concern to the charter’s governing board, Twin Rivers, Sacramento COE, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the State Controller’s Office, and require immediate intervention to limit the risk of fraud and misappropriation of assets in the future. The FCMAT audit specifically recommended that the Sacramento County Superintendent (county superintendent) ensure that both Twin Rivers and Highlands investigate and properly address the issues that it raised in the audit. The audit also recommended that the county superintendent notify the appropriate agencies, such as CDE and the State Controller’s Office, regarding weaknesses and illegal fiscal practices so that suitable actions could be taken.

Substantial media scrutiny of Highlands began in January 2024 when a news outlet began publishing a recurring investigative journalism series exploring concerns regarding Highlands’ operations. The series investigated concerns at Highlands including conflicts of interest, attendance reporting, excessive and lavish spending, fiscal policies, and lack of oversight. Highlands’ former executive director served in that position from July 2015 until he resigned in June 2024, the month after this audit was approved. On July 1, 2024, Highlands appointed a long‑time contractor and Twin Rivers’ former deputy superintendent as its executive director. In April 2025, after the majority of our audit fieldwork had been completed, Highlands’ board approved a plan to reduce its numbers of teachers, staff, and classified management by about 87 percent, going from more than 700 full-time equivalent employees to fewer than 95, and reducing the number of students it enrolls from 13,000 to 3,300 students. Highlands’ executive director explained to the board that the reduction stems from the recently communicated requirement that Highlands teachers must hold a K–12 credential.

Audit Results

- Highlands Received More Than $180 Million in K–12 Funds for Which It Was Not Eligible

- Highlands Has Engaged in Wasteful Spending and Inappropriate Hiring Practices

- Unqualified Teachers and Large Student Enrollment May Contribute to Poor Student Outcomes at Highlands’ Schools

- Twin Rivers and Other Educational Entities Did Not Provide Adequate Oversight of Highlands

Highlands Received More Than $180 Million in K–12 Funds for Which It Was Not Eligible

Key Points

- By not meeting the funding requirements for classroom‑based or nonclassroom‑based instruction, Highlands Community Charter and Technical Schools (Highlands) was not eligible to receive $177 million in K–12 funding for its classroom‑based school during fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24.

- From fiscal year 2021–22 through 2023–24, Highlands improperly collected more than $5 million—$3.5 million in addition to the $177 million—in K–12 funds by misreporting its attendance to the California Department of Education (CDE).

- Highlands lacked documentation to support its reported attendance for all 18 Highlands Community Charter School (HCCS) students and one of the 30 California Innovative Career Academy (CICA) students we reviewed, weakening its ability to withstand public scrutiny and resulting in some disallowable funding for CICA’s attendance.

HCCS Was Not Eligible to Receive $177 Million in K–12 Funding

Highlands has inappropriately collected millions in K–12 funding because it has not met the legal requirements for the mode of student instruction it claims to offer. State law defines two modes of instruction: classroom‑based instruction, which occurs primarily at a schoolsite, and nonclassroom‑based instruction, such as online independent study, and establishes different funding requirements for each mode. As Figure 4 shows, Highlands has not met the conditions for collecting K–12 funding for classroom‑based instruction over the last two years for HCCS, and because it has not received a determination of funding for HCCS from the State Board of Education, we conclude that it is also ineligible for funding for nonclassroom‑based instruction.3 Therefore, it is our view that Highlands was not eligible to receive any of the K–12 funding it received for HCCS from fiscal years 2022–23 through 2023–24, a total of more than $177 million.

Figure 4

HCCS Has Not Met Key Conditions of K–12 Funding

Source: State law, HCCS documentation, and auditor observations.

Figure 4 shows key conditions of K-12 funding and the ways HCCS has not met them. There are two columns. The left column has a yellow illustration of a K-12 school with a blue dollar sign on it above the column heading. The column heading is a blue box and reads “Key Conditions of K-12 Funding.” The right column has a yellow illustration of a document that is titled “HCCS” and has a blue X on it above the column heading. The column heading is a yellow box and reads “Condition Met by HCCS?” In the left-hand column, in the first row, there is a blue circle with the number 1 in it, and next to it reads “To be eligible for funding, classroom-based instruction occurs only when charter school students are engaged in required educational activities under the immediate supervision and control of a certificated charter school employee, and at least 80 percent of the offered instructional time is at the schoolsite.” To the right of this in the right-hand column is a yellow circle with an X in it. Next to it reads “No. While HCCS provides instruction at schoolsites, we observed during seven class visits that HCCS typically provides classroom-based instruction for only 2-3 hours of a scheduled 6-hour school day.” On the left-hand column, in the second row, there is a blue circle with the number 2 in it. Next to it reads “In order to qualify for funding for classroom-based instruction, charter schools must require students to attend at the schoolsite for at least 80 percent of the required minimum instructional time.” To the right of this in the right-hand column is a yellow circle with an X in it. Next to it reads “No. In addition to Highlands’ insufficient attendance policies, we observed in eight class visits that in practice students entered and left class at various times—in some cases leaving immediately after signing in for attendance—and teachers did not attempt to enforce any attendance requirement.” On the left-hand column, in the third row, there is a blue circle with the number 3 in it. Next to it reads “If a charter school does not meet the above requirements, state law classifies it as providing nonclassroom-based instruction and allows it to receive K-12 funding for nonclassroom-based instruction only if the State Board of Education determines it is eligible for funding.” To the right of this in the right-hand column is a yellow circle with an X in it. Next to it reads “No. HCCS has never received a determination of funding for nonclassroom-based instruction.”

HCCS must meet funding requirements relating to the amount of instruction it offers. State law requires, as a condition of apportionment, that charter schools offer a minimum of 64,800 minutes of instruction each fiscal year to students in grades 9 to 12. Compliance with the instructional minutes requirement is assessed in the annual audits of charter schools, and the Guide for Annual Audits of K–12 Local Education Agencies and State Compliance Reporting (K–12 audit guide) published by the Education Audit Appeals Panel instructs auditors to compare bell schedules, academic calendars, or other comparable documentation to determine the number of instructional minutes offered by a classroom‑based school. We determined that HCCS’ calendars and bell schedules contain enough minutes over the course of its academic calendar to offer the amount of instructional time required by law. This conclusion is consistent with Highlands’ most recent annual audit for fiscal year 2022–23. However, a charter school’s eligibility for funding also depends on whether it meets requirements relating to the mode of instruction it offers, which may be either classroom based or nonclassroom based.

There are two key conditions that a charter school must meet to receive K–12 funding for classroom‑based instruction. First, state law requires charter schools that offer classroom‑based instruction to offer at least 80 percent of their instructional time at the schoolsite. According to state law, classroom‑based instruction occurs only when charter school students are engaged in required educational activities and are under the immediate supervision and control of a certificated employee.4 Second, these schools must require the attendance of all students at the schoolsite for at least 80 percent of the minimum instructional time required by law. These requirements are a condition of receiving funding for classroom‑based instruction in K–12 schools. In other words, failure to meet these requirements makes HCCS or any other charter school ineligible for classroom‑based funding for their students.

In our visits at seven classes in different locations, we observed that teachers lectured for only two to three hours. One additional instructor, not included in those seven classes, informed us that they typically lecture for two to three hours each day. Most of those instructors informed us that they used the rest of the scheduled class session as optional time for students to receive individualized help. Rather than having classes in different subjects throughout the day, HCCS’ classes often covered multiple subjects and were scheduled for the entire school day, which is typically six hours. We observed that nearly all of the remaining students left the class after the teacher finished the lesson. We also observed students arriving to class at various times and leaving at various times, and we did not observe any instructor who attempted to enforce a requirement for attendance in any way. Highlands’ executive director confirmed that some of HCCS’ teachers reported providing instruction for two to three hours in a day while students attended classes and leaving the remainder of the scheduled day open to work on lesson plans or to serve as an optional study period to meet the needs of its adult student population, who had varying schedules outside of school. In our view, the portion of the school day that is optional does not meet the definition of classroom‑based instruction that appears in state law because, even if the teacher remains in the classroom to work on lesson plans or answer students’ questions, this is not a required educational activity for the students.

HCCS students may also engage in instructional activities through online programs or by completing assignments at home. For example, some of HCCS’ courses involve online instruction through programs such as Edmentum, which offers digital K–12 curricula, assessments, and instructional services, and we observed teachers giving students who chose not to stay in class packets of course materials to complete at home. However, instruction that occurs offsite satisfies neither the first key legal requirement nor Highlands’ own policy that at least 80 percent of HCCS’ total instructional time will be at a schoolsite. In fact, state regulations provide that the legal requirement to be at the schoolsite is not satisfied if the students are in a personal residence, even if space in the residence is set aside and dedicated to instructional purposes. Additionally, in our view these instructional activities do not meet the legal definition of classroom‑based instruction because they do not occur under the immediate supervision and control of a certificated employee. Because the amount of classroom‑based instruction we observed was typically less than half of the instructional time shown on the bell schedule, we conclude that Highlands offered significantly less than 80 percent of its instructional minutes at the schoolsite.

Additionally, by not requiring students to attend class for a sufficient amount of time, Highlands does not meet the second key requirement of classroom‑based instruction, which is that it must require the attendance of all students at the schoolsite for at least 80 percent of the 64,800 minutes of instruction required by state law. While Highlands’ student handbook communicates that its students are expected to attend school daily and stay for the entire program of study, our observations found that Highlands did not require students to do so. As discussed above, the instructors we spoke to indicated that a portion of the class day—typically more than half of the scheduled class period—was optional for students. Highlands’ executive director also confirmed that students have not been required to attend for 80 percent of the offered instructional minutes because the previous administration focused on enrollment and not attendance. Further, Highlands lacked policies related to consequences for failure to attend. In fact, in eight class visits, we observed students arriving and leaving at various times, with no attempt to enforce a requirement for attendance. In three of those eight class visits, we observed students signing into class and then immediately leaving with no instructor attempting to enforce a requirement for attendance. One instructor, not included in these three class visits, informed us that there are students that sign in and leave immediately every day, but usually less than five students per day. Furthermore, a January 2025 review of Highlands commissioned by Twin Rivers Unified School District (Twin Rivers) noted that some classes lacked the physical capacity for their rosters, stating that students may be sent home to work on assignments or to wait until a spot opens. In light of this observation, that review questioned whether HCCS is offering the scheduled instructional minutes, meeting the obligation of offering at least 80 percent of instructional time at the schoolsite, or requiring students to physically attend for 80 percent of the time. We also conducted a survey of current and former Highlands students and asked how many hours per day students attended classes in person at Highlands on average. In response to this survey, 29 percent of students responded that they attended classes for only one to two hours per day. We present the full results of the survey in Appendix B.

In seeking to understand why students would sign in to classes and then immediately leave, we found that there may be an incentive for students to do so for purposes unrelated to education: receiving credit toward work participation requirements under the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program (CalWORKs). CalWORKs is California’s implementation of the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant to help low‑income families with children achieve economic self‑sufficiency and is administered by county offices of human assistance. Eligibility for CalWORKs generally requires participation in welfare‑to‑work activities, which may include activities related to education. In October 2024, Highlands reported the hours of participation of more than 8,000 students to various counties’ departments of human assistance. Highlands’ student onboarding and records manager indicated that its method for tracking student attendance does not record the actual time students receive instruction and only records whether a student is present or absent for the day. Nonetheless, Highlands reports seven hours of student participation—including six hours of in‑person instructional time and one hour of study time—for every day it has recorded a student as present to the county departments of human assistance responsible for administering CalWORKs, regardless of a student’s actual hours of participation. Consequently, Highlands may be overstating hours of participation for those students who may receive CalWORKs benefits.

Because we conclude that HCCS does not meet the requirements for K–12 funding for classroom‑based instruction, we followed the instructions in the K–12 audit guide and assessed whether it qualified for funding under the requirements for nonclassroom‑based instruction. State law provides that instruction that does not meet the definition of classroom‑based instruction is considered nonclassroom‑based instruction, which is subject to more stringent funding requirements than classroom‑based instruction. State law contains several conditions of funding for nonclassroom‑based instruction, including a requirement that a charter school obtain a determination for funding from the State Board of Education if more than 20 percent of its instruction is not classroom‑based. The audit guide likewise states that if more than 20 percent of a charter school’s average daily attendance (ADA) is generated from nonclassroom‑based instruction and the school does not have a funding determination, the charter school is not eligible for ADA generated through nonclassroom‑based instruction.

While Highlands’ policies state that as a classroom‑based charter school HCCS may only offer a limited amount of nonclassroom‑based instruction, in our observations the portion of the school day that did not satisfy the requirements of classroom‑based instruction exceeded 20 percent of the total instructional time scheduled for that day. In addition to our observations of online learning and take‑home packets, in our survey of students, more than half responded that they completed seven or more hours of schoolwork or studying per week outside of the classroom, which is more than 20 percent of the instructional time Highlands offers in its bell schedules per week. We therefore conclude that HCCS is offering nonclassroom‑based instruction at a rate that exceeds the 20 percent threshold. We reviewed the funding determinations made by the State Board of Education pursuant to state law and found that HCCS has not received a determination of funding for nonclassroom‑based instruction. Therefore, in addition to not qualifying for funding for classroom‑based instruction, it is our view that HCCS did not qualify for funding for nonclassroom‑based instruction either.

Although Highlands has recently adopted policies in March of 2025 that require students to be present for at least 80 percent of the scheduled instructional hours weekly or else face potential enforcement or intervention, Highlands’ executive director stated that he does not believe requiring students to do so is a condition for receiving ADA apportionment. As discussed above, Highlands’ executive director explained that students have been offered the required number of instructional minutes but have not been required to attend for at least 80 percent of the offered minutes because the previous administration focused on enrollment and not attendance. Highlands’ associate deputy director explained that attendance for adults is noncompulsory so students may arrive late and leave early. We agree that adult students are not subject to the compulsory education requirements of state law and would not be considered truant for failing to attend class. However, the explanation offered by the executive director does not address the fact that the compulsory education provisions are distinct from the K–12 funding requirements for classroom‑based instruction and there is no exception to the 80 percent on‑site attendance requirement for adult students, although we acknowledge that state law does not expressly address this issue.

As noted above, we observed that the actual practice of HCCS was to stop providing classroom‑based instruction well before the end of the scheduled class period and not require students to remain in attendance after that point. In our view, this does not meet the requirements of state law and the K–12 audit guide, which both identify the requirement to offer 80 percent of instruction at the schoolsite and require the attendance of students at the schoolsite for at least 80 percent of the required time as conditions of classroom‑based funding. Because it did not meet these requirements, or the funding requirements for nonclassroom‑based instruction, we conclude that HCCS was not eligible to receive the $104.6 million in K–12 funding it received in fiscal year 2023–24 and likewise was ineligible to receive $72.7 million in fiscal year 2022–23—amounts which likely made up nearly 60 percent of Highlands’ total revenues in those years.

Highlands Has Inappropriately Received More Than an Estimated $5 Million in K–12 Funds for Misreported and Unsupported Attendance

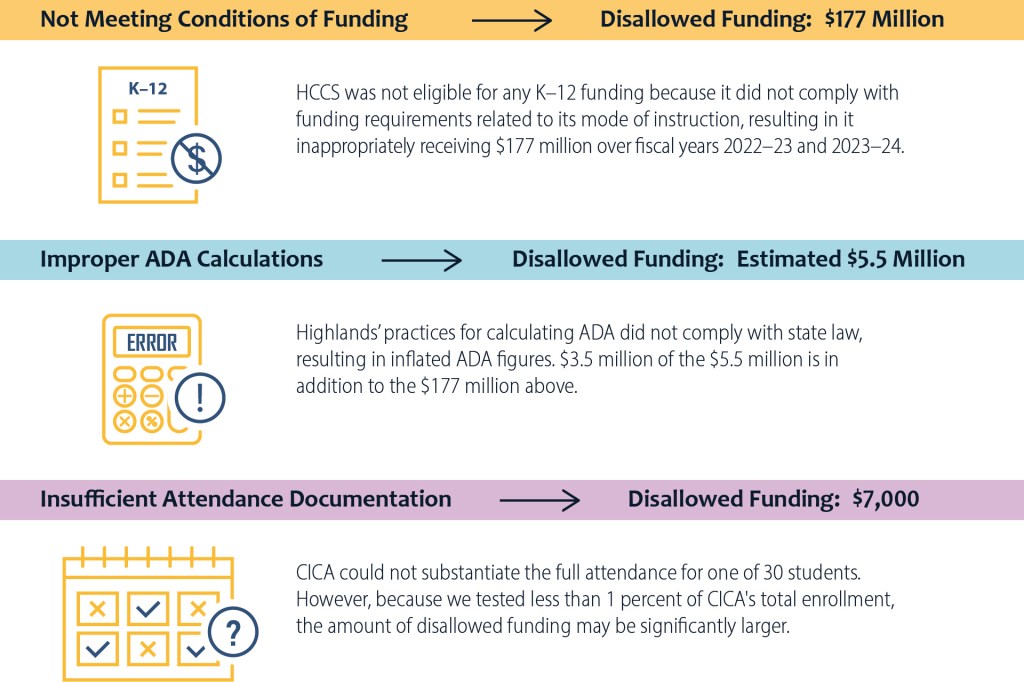

Highlands misreported its ADA from fiscal years 2021–22 through 2023–24, resulting in it receiving millions of dollars in overpayments. As mentioned in the Introduction, charter schools receive state funding based on ADA. Charter schools calculate ADA by dividing the total unique days of attendance by the number of educational days. They then report this figure to CDE throughout the school year in full school months, which consist of four school weeks. We obtained Highlands’ student attendance data, reviewed Highlands’ methodologies and state law, and calculated its ADA figures for fiscal years 2021–22 through 2023–24. We found that Highlands’ past practices for calculating ADA did not comply with state law, and our figures did not agree with the ADA Highlands reported to CDE. As a result of not calculating its ADA correctly, Highlands received an estimated $5.5 million in overpayments, of which $3.5 million is in addition to the $177 million in disallowed funding we discussed earlier in the report.5 We calculated these amounts by multiplying the difference between our calculated ADA and Highlands’ reported ADA by the appropriate funding values.

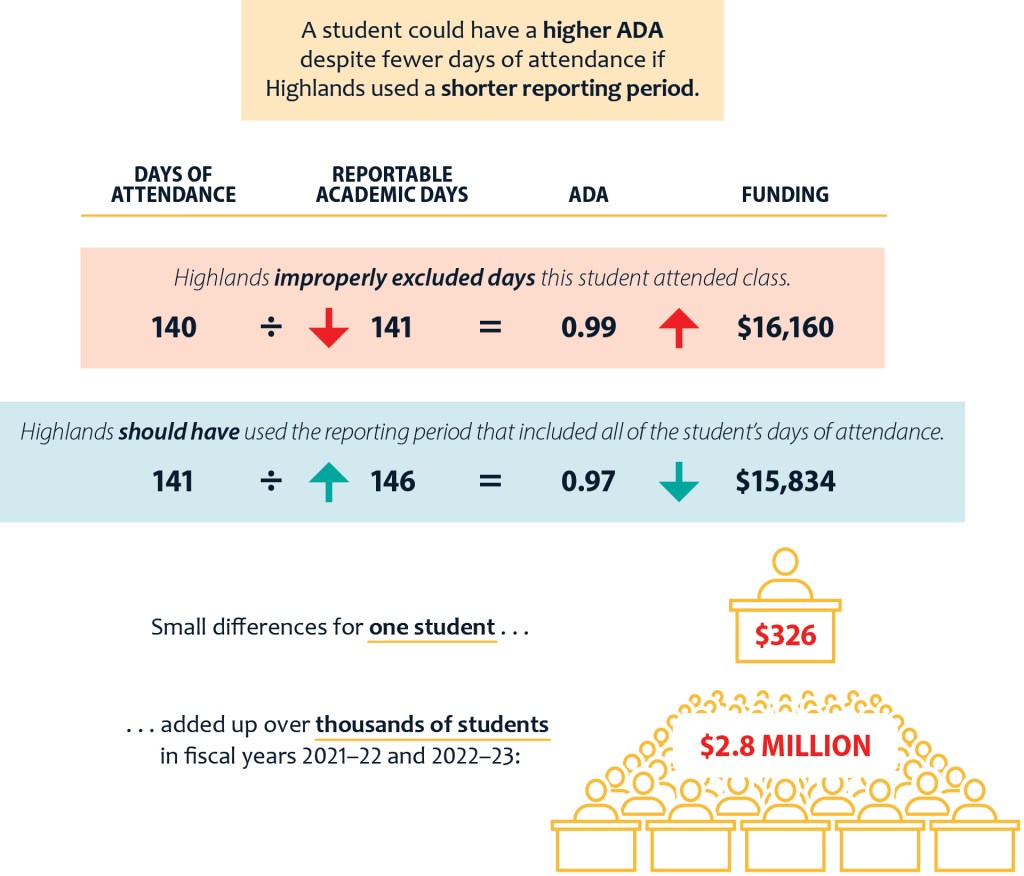

A significant portion of these overpayments resulted from Highlands inappropriately omitting periods of lower attendance from students’ ADA when it reported ADA to CDE. State law allows charter schools some flexibility in how they develop reporting calendars and academic tracks but nonetheless requires schools to report all of a student’s days of attendance. However, Highlands intentionally reported students’ attendance in a manner that omitted periods of lower attendance when doing so increased the students’ ADA for the school year. Specifically, Highlands did not report attendance periods for all students that aligned with the students’ first day of attendance. Instead, Highlands reported certain students’ attendance as if the students had begun attending its schools at a later date, improperly excluding earlier periods in which those students had lower attendance. Including those earlier periods would have resulted in lower ADA than that which Highlands ultimately reported to CDE. Consequently, Highlands artificially inflated its overall average attendance in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23, which resulted in it inappropriately receiving an estimated $2.8 million in K–12 funding, as we show in Figure 5. Highlands explained that, in past years, it believed state law did not address the complexities of its education model and therefore allowed it to exclude dates of attendance in this way. However, both state law and CDE state that charter schools must include all days a student attended when calculating ADA.

Figure 5

A Hypothetical Example Demonstrating How Highlands Generated More Funding by Excluding Days of Attendance

Source: State law and Highlands’ attendance data.

Figure 5 shows a hypothetical example of Highlands excluding days of attendance for a student and the calculation of funding this example would generate in comparison to how Highland should have calculated attendance. At the top of the figure is a yellow box that reads “A student could have a higher ADA despite fewer days of attendance if Highlands uses a shorter reporting period.” Below this are four headings over a yellow line. From left to right, these headings are “Days of Attendance,” “Reportable Academic Days,” “ADA,” and “Funding.” Underneath these headers is a long light red rectangle. At the top of the rectangle is the statement “Highlands improperly excluded days this student attended class.” Below that, aligned with the “Days of Attendance” heading, is the number 140. To the right of that is the division sign, followed by a red arrow pointing down. To the right of that, aligned with the “Reportable Academic Days” heading, is the number 141. To the right of that is the equal sign. To the right of that, aligned with the “ADA” heading, is the number 0.99. To the right of that is a red arrow pointing up. To the right of that, aligned with the “Funding” heading, is the number $16,160. Below the red rectangle is a wider light green rectangle. At the top of the rectangle is the statement “Highlands should have used the reporting period that included all of the student’s days of attendance.” Below that, aligned with the “Days of Attendance” heading, is the number 141. To the right of that is the division sign, followed by a green arrow pointing up. To the right of that, aligned with the “Reportable Academic Days” heading, is the number 146. To the right of that is the equal sign. To the right of that, aligned with the “ADA” heading, is the number 0.97. To the right of that is a green arrow pointing down. To the right of that, aligned with the “Funding” heading, is the number $15,834. Below the light green rectangle, on the left, is the statement “Small differences for one student…” with one student bolded and underlined with a yellow line. To the right of that statement is a yellow illustration of a student behind a desk with “$326” in red over the desk. Below the statement on the left is another statement that reads “…added up over thousands of students in fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23:” with thousands of students bolded and underlined with a yellow line. To the right of that statement is a yellow illustration of many students behind desks with “$2.8 million” in red over the students.

Highlands Lacks Reliable Documentation to Support Its Reported Attendance

We found that HCCS cannot support the attendance it reported for funding with verifiable documentation for all 18 of the HCCS students we reviewed. State law requires charter schools to maintain written contemporaneous records that document all pupil attendance, and Highlands’ electronic attendance reporting system (attendance reporting system) satisfies this requirement. However, Highlands has faced scrutiny over its attendance reporting, and our testing found no combination of paper or electronic attendance records—and in some cases no documentation—that matched the attendance Highlands’ teachers reported within its attendance reporting system from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24. Highlands’ associate deputy director explained that because of increased pupil enrollment, it did not standardize its attendance processes with written policies or, before fiscal year 2023–24, require teachers to retain paper attendance sheets. The lack of supporting attendance records and policies for attendance prevents Highlands from demonstrating the accuracy of its reported classroom‑based attendance at HCCS, which is used to calculate state K–12 funding.

We also found weaknesses in the support Highlands maintained for student attendance at CICA. State law requires schools operating independent study programs to compute ADA based, in part, on the daily time value of work products, as personally judged by a certificated employee. To comply with this, CICA requires its students and teachers to sign periodic learning reports that affirm that the student completed schoolwork. To support this, each learning report should contain two work products completed by the student during the attested period. However, in our review of the attendance for a selection of 30 students, we found one student for whom Highlands did not have enough learning reports to support more than three months of attendance. This resulted in more than $7,000 in disallowed funding, though our selection of 30 was less than one percent of CICA’s overall enrollment of 3,000 students. We include this and the other ways we found that Highlands inappropriately received attendance enrollment funding in Figure 6. CICA does not have written policies and procedures for how it records attendance and could not explain why it did not have learning reports covering the attendance reported for this student. Additionally, while the laws governing independent study are not prescriptive about what a student work product must contain to be given a time value, we identified that the work products of all 30 students lacked the student’s name or a date. Therefore, in our opinion there is a more than remote likelihood that CICA’s learning reports are inaccurate.

Figure 6

Highlands Inappropriately Received Funds in a Variety of Categories

Source: State law, CDE documentation, Highlands documentation, and auditor analysis.

Figure 6 shows how Highlands inappropriately received funds in three different categories. At the top of the figure is a wide yellow bar. In the left part of the bar is the statement “Not Meeting Conditions of Funding” in blue. In the middle is a blue arrow. On the right is the statement “Disallowed Funding: $177 million” in blue. Under the yellow bar, on the left, is a yellow illustration of a document that says “K-12” in blue at the top. There is a blue circle with a dollar sign and a line across it on top of this document. To the right of this illustration, also under the yellow bar, is the statement “HCCS was not eligible for any K-12 funding because it did not comply with funding requirements relating to its mode of instruction, resulting in it inappropriately receiving $177 million over fiscal years 2022-23 and 2023-24.” Below this illustration and statement is a wide blue-green bar. On the left is the statement “Improper ADA Calculations” in blue. In the middle of the bar is a blue arrow. On the right is the statement “Disallowed Funding: Estimated $5.5 Million” in blue. Under the blue-green bar, on the left, is a yellow illustration of a calculator that has an ERROR message in blue. There is a blue circle with an exclamation point in it on top of this calculator. To the right of this illustration, also under the blue-green bar, is the statement “Highlands practices for calculating ADA did not comply with state law, resulting in inflated ADA figures. $3.5 million of the $5.5 million is in addition to $177 million above.” Below this illustration and statement is a wide pink bar. On the left is the statement “Insufficient Attendance Documentation” in blue. In the middle of the bar is a blue arrow. On the right is the statement “Disallowed Funding: $7,000” in blue. Under the pink bar, on the left, is a yellow illustration of a calendar that has some days with a yellow “X” on them and some days with a blue checkmark on them. There is a blue circle with a question mark in it on top of this calendar. To the right of this illustration, also under the pink bar, is the statement “CICA could not substantiate the full attendance for one of 30 students. However, because we tested less than one percent, the amount of disallowed funding may be significantly larger.”

Highlands Has Engaged in Wasteful Spending and Inappropriate Hiring Practices

Key Points

- Highlands has made expenditures that waste public funds and violate state law, including prohibitions against conflicts of interest and gifts of public funds.

- Highlands has violated the few purchasing policies it has by not receiving board approval for large contracts and purchases, therefore impeding public transparency of its expenditures.

- Highlands has hired and promoted employees who are not qualified for their roles and has inadequate protections against nepotism.

- Highlands does not have written policies and procedures for assigning salaries and bonuses to its employees, and therefore lacks controls to prevent favoritism and ensure that employees receive compensation equitably.

Highlands Has Wasted Public Funds, Made Extravagant Travel Expenditures, and Spent Unjustified Amounts on Marketing

Highlands’ inappropriate use of public funds has violated state law, best practices, and its own internal policies. Highlands receives public funding to operate and is therefore subject to the California Constitution’s prohibition on the gift of public funds. To avoid violating this prohibition, when a charter school provides public money or resources to another entity, it must ensure that the money will be used to further the specific public purposes for which the school was created. This means that as a charter school, Highlands’ expenditures must serve an educational purpose. In our review of 30 transactions at Highlands from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, we identified 15 transactions that Highlands was unable to demonstrate served an educational purpose. For example, we questioned the educational purpose of an $80,000 registration payment for the Independent Voter Project Business and Leadership Policy Conference, as item six in Table 1 shows. This total covered seven days of attendance and lodging for seven employees and one consultant at the Fairmont Kea Lani in Maui, where the conference occurred. Highlands also paid $1,630 for an additional night at the hotel for one employee as well as flights for its employees, in addition to the $80,000 registration payment. Given the lack of apparent educational purpose, this expenditure raises concerns about whether it is an impermissible gift of public funds. Further, we identified two other transactions that violated the gift of public funds prohibition. Finally, we also identified a transaction that violated state law prohibiting conflicts of interest. Beyond the concerns about questionable educational purposes, Table 1 includes a selection of the total transactions we reviewed and our other accompanying concerns, as well as Highlands’ perspective on the purpose of the expenditures.

We identified two concerning transactions that benefited spouses of current director‑level employees at Highlands. In one, a director‑level employee initiated a contract for a $1,500 per month payment to his spouse for mentor services, as item one in Table 1 shows. In this instance, the forming of the contract constituted a violation of state laws that generally prohibit a government official, acting in his or her official capacity, from making or influencing a contract or governmental decision in which he or she has a financial interest. The director stated that he was unaware this was a violation and that he had not received any training from Highlands about it being a violation. In another concerning transaction, Highlands spent about $8,750 on blankets that it stated were a holiday gift for students, as item two in Table 1 shows. The spouse of a director‑level employee owns the company that was the vendor for this transaction. While we obtained no evidence that indicates that the director‑level employee influenced the decision to purchase blankets from his spouse, it raises concerns about Highlands’ ability to prevent conflicts of interest in its purchasing practices. Highlands spent a total of $397,960 with this vendor from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24. Further, because the blankets that Highlands purchased for $8,750 were a holiday gift to students and did not serve an educational purpose, this expenditure violated the prohibition on the gift of public funds.

As a steward of public funds, Highlands should adhere to best practices on internal controls, which can help protect against waste and abuse of funds. Government Auditing Standards define waste as the act of using or expending resources carelessly, extravagantly, or to no purpose. Importantly, the standards say, waste can include activities that do not include abuse and does not necessarily involve a violation of law. Rather, waste relates primarily to mismanagement, inappropriate actions, and inadequate oversight.

Highlands had vague and inconsistent contracting language that did not ensure adequate justification of the contract vendors and amounts, which resulted in wasteful contracts. In one example, Highlands entered into a contract with an individual for student outreach and support services that commenced on September 1, 2022, and ended December 20, 2022. The contract authorized two $30,000 payments, one in early October and one in early November 2022, for a total of $60,000, as item nine in Table 1 shows. Highlands’ own policy for consulting contracts requires that the agreement clearly state the purposes of the contract, a statement of work, and a clear description of what the consultant’s end product shall be, among other requirements. As the text box shows, the contract stated that its purpose was student recruitment and awareness but lacked a clear statement of work and a clear description of the end product. Highlands’ chief business official stated that the purpose of the contract was to develop partnerships with certain organizations, such as a cosmetology school, for Highlands’ planned expansion into the cities of Garden Grove and Elk Grove. However, Highlands was unable to demonstrate any specific outcome of this contract, and the available evidence does not justify the $60,000 total for the contract for three months of work. We find it concerning that Highlands did not define clear contract deliverables that would have provided greater transparency and clarity regarding the extent and timing of the services provided.

Stated Scope of Services for This Contract:

I. Support and ongoing student recruitment in support of the Garden Grove expansion. Bring awareness to the local community about the opportunities and experiences offered by Highlands Community Charter Technical Schools.

II. Student awareness and outreach in the Orange County region.

III. Student awareness and outreach in the Elk Grove region.

IV. Student education on programs, services, activities, career paths, or expertise to those outside the traditional education community.

Source: Memorandum of understanding between Highlands and this consultant.

Highlands also had a practice of spending unjustified amounts of K–12 funding on sponsorships of athletic programs, chamber of commerce foundations, and political organizations, which—in our opinion—appears wasteful and raises questions about whether they were for an appropriate purpose. Highlands’ director of student engagement stated that the purpose of these sponsorships is advertisement and recruitment, which may serve an educational purpose, but in most sponsorships we reviewed, Highlands was not able to demonstrate a tangible marketing outcome. In one example, Highlands purchased a $25,860 sponsorship of Foothill High School Athletics, as item 10 in Table 1 shows. Highlands’ director of student engagement asserted that the sponsorship included the placement of banners on Foothill High School’s field fences and gymnasium, but did not retain any evidence that this marketing occurred. However, the $25,860 paid by Highlands for this sponsorship was the exact cost of multiple quotes for sporting equipment, such as a golf cart and batting mats, for Foothill High School. Foothill High School sent a list of sporting equipment and their accompanying quotes to Highlands stating, “we thank you for all you have done and your support of Foothill athletics.” The lack of documented marketing activities and the sponsorship amount call into question Highlands’ assertion that this payment was primarily for a marketing purpose.

The problems we identified during our testing of 30 transactions can be largely attributed to Highlands’ lack of internal controls over its spending, including documented policies and procedures. Documented policies and procedures are a necessary component of internal controls because they better position an organization to design, implement, and operate its controls effectively. Further, documented policies are important because they establish expectations over accountability and set different responsibilities for those involved in the purchasing process. The current executive director considers any improper expenditure practices at Highlands to have stemmed from the absence of formal purchasing procedures, not the substance of the purchases themselves. He considers K–12 funding laws to be permissive and that any expense can be appropriate if it goes through a formal approval process that documents the justification for the expense and the vendor. However, as stated earlier in this section, expenditures of K–12 funding by a charter school must serve an educational purpose or the school risks violating the prohibition on the gift of public funds. FCMAT also states that one way to assess whether a purchase is appropriate is through a public scrutiny test. This test means asking whether the tax‑paying public would view the expenditure as necessary to support public education. Highlands’ chief business official asserts that the absence of policies and procedures for processes like vendor selection is because of the absence of any legal requirement to have them. However, as FCMAT’s best practices state, because current laws do not cover all aspects of charter school operations, FCMAT provides a manual that goes beyond the law and official regulations to include information on best practices and sound internal controls essential to successful charter school operations throughout California. Without best practices in place, Highlands runs the risk of continued questionable or wasteful spending.

Highlands Did Not Always Comply With the Few Purchasing Policies It Had, Reducing Transparency to the Public

Highlands has not consistently complied with the limited purchasing policies it has had in place. For example, Highlands has had a policy since November 2021 to present consulting contracts of more than $100,000 to the Highlands board of directors (Highlands’ board) for approval. We reviewed six contracts in total, and we identified two contracts from fiscal year 2023–24 for amounts over $100,000 that did not go before Highlands’ board for approval. The chief business official stated that the lack of approval from Highlands’ board stemmed from training deficiencies and lack of bandwidth. We also identified expenditures for a contracted consultant that exceeded $100,000 in the same fiscal year. While the actual costs exceeded the approval threshold that year, the contract itself lacked a maximum dollar amount, contrary to Highlands’ purchasing policy. The chief business official stated that, because the original contract did not include enough specificity on the expected cost, Highlands did not have sufficient data to anticipate an overall cost for work during the year. Thus, Highlands did not follow its own policy and bring the contract before its board for approval. Highlands’ board has since approved these contracts in May and June 2024. The chief business official stated that Highlands has since assigned its accounts payable manager to ensure constant monitoring of Highlands’ fiscal policy compliance. He also stated that Highlands has adopted new contract templates to ensure consistency across the organization. While this template includes a maximum dollar amount clause, which would enable Highlands to more easily comply with its board approval policy, this does not negate the necessity for stronger internal controls to ensure compliance.

In 2023, Highlands also implemented a policy to obtain approval from its board for purchases over $1 million, but we identified two purchases over $1 million from fiscal year 2023–24 that did not receive approval from its board. One was for a T‑Mobile transaction that totaled approximately $1.7 million. The other was for a Manchester Grand Hyatt San Diego bill that, in aggregate, cost approximately $1.2 million. The chief business official stated that its fiscal services department interpreted the T‑Mobile bill by line item rather than total, and that the Manchester Grand Hyatt bill did not include any individual points‑of‑sale over $1 million. As a result, Highlands did not subject them to the approval requirement for a purchase over $1 million. Such an interpretation circumvents its controls of obtaining board approval for large purchases, risking wasteful spending. The chief business official stated that there was no intentional choice to structure these payments in order to circumvent the policy at the time. He added that it is his opinion that in cases such as these, no matter the circumstance, if a transaction crosses the threshold, it should become a board action. The chief business official also stated that this general practice has changed, and that Highlands now presents composite purchases that total over $1 million to its board for approval. He presented the T‑Mobile purchases to the board for retroactive approval in June 2024. However, Highlands only presented the Manchester Grand Hyatt total cost to the board as an informative item after the purchase. It never received formal approval, and, in fact, the purchase should have been approved before it took place. Additionally, regardless of approval, this purchase indicates wasteful spending of K–12 funding.

The policies Highlands does have are also insufficient for ensuring transparency to the public. FCMAT states that one of the fiduciary responsibilities for the executive director, board, and other key management personnel at a local educational agency (LEA) is the duty of disclosure. One outcome of requiring board approval for large purchases is that it subjects those approvals to the Ralph M. Brown Act, which generally requires that the meetings of local boards, including charter school boards, be open to the public. By allowing the executive director to make purchases up to $1 million without board approval, including any nonconsultant contract, Highlands can obscure its financial decision‑making above certain thresholds from the public. This approval threshold is far higher than that used by other LEAs. Twin Rivers, for example, has a board policy that requires board approval for all contracts over $35,000. Additionally, state law requires school district governing boards to competitively bid and award any contracts involving an expenditure of more than $50,000, adjusted for inflation, to the lowest responsible bidder. The State Superintendent of Public Instruction annually adjusts the $50,000 amount specified in state law, and some school districts authorize their superintendents to make purchases under that annual amount. In 2025, that amount is $114,800. While Highlands is not subject to this law, it demonstrates the common practice at other LEAs. In January 2025, Highlands updated its purchasing authority limits to require all purchases over $250,000 to receive board approval.

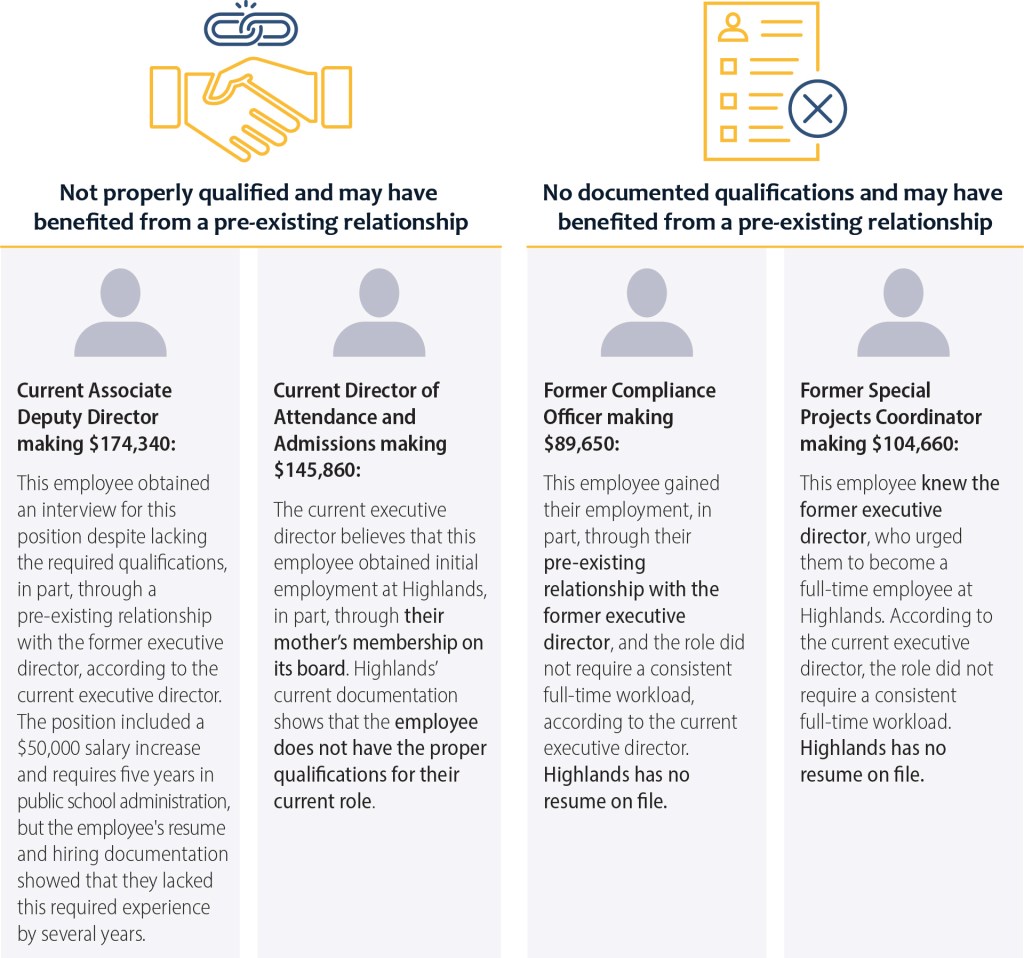

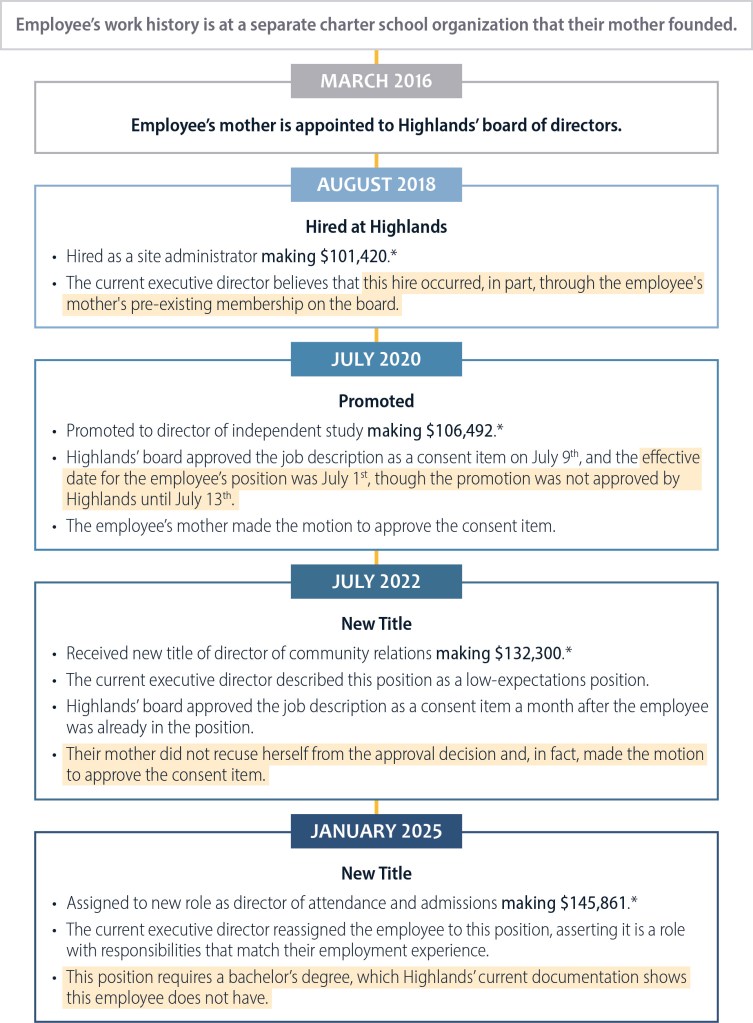

Highlands Hired and Promoted Unqualified Individuals and Had Inadequate Protections Against Nepotism