I2024-1 Investigations of Improper Activities by State Agencies and Employees

Waste and Inefficiency, Improper Hiring, and Other Improper Governmental Activities

Published: November 21, 2024Report Number: I2024-1

November 21, 2024

Investigative Report I2024-1

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

The California Whistleblower Protection Act authorizes my office to publish the following report that summarizes some of the investigations of alleged improper governmental activities that we have recently completed. This report details eight substantiated allegations involving several state agencies. Our investigations found waste and inefficiency, improper hiring, and other improper governmental activities totaling nearly $2.6 million.

In one example, we found that an agency did not deposit a check for nearly $875,000 that had been in its receipt for two years. This error resulted from accounting staff not following its internal controls and then losing track of the payment. Another case involves a manager who operated a personal business in which he coached prospective state employees on how to embellish or falsify their qualifications when applying for state jobs. Our investigation focused on three of the manager’s clients and found that they received unlawful appointments. The manager used his own methods to unlawfully obtain state positions for himself. In yet another example, a chief information security officer (CISO) violated the law when he improperly provided to a job candidate 35 job applications containing confidential information. The CISO sent the information to the job candidate to help him understand the qualifications of the other candidates he would be competing against for the position.

State agencies must report to my office any corrective or disciplinary action they take in response to recommendations we have made. Their first reports are due within 60 days after we notify the agency or authority of the improper activity, and they continue to report monthly thereafter until they have completed corrective action.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Summary

Results in Brief

Under the authority of the California Whistleblower Protection Act, the California State Auditor’s Office (State Auditor) conducted investigative work from January 1, 2023, through December 31, 2023, on 1,306 allegations of improper governmental activity. Some of these investigations substantiated improper activities, including waste and inefficiency, improper hiring, and other improprieties. We provide information in this report on only a selection of the cases we have investigated as a deterrent for state agencies and state employees so they might avoid similar improper governmental activities.

Department of Health Care Services

An accounting supervisor with the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services) failed to deposit a check for nearly $875,000 from the county of Los Angeles more than two years ago. Health Care Services’ failure to promptly deposit the check resulted in waste and inefficiency.

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

The California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA) did not promptly identify travel expenses that lacked support justifying a business purpose. As a result, nearly 150 current and former employees incurred more than $92,000 for unsupported travel expenses that occurred before 2024. CDFTA’s delay in identifying travel expenses that lack support also prevented the department from efficiently recovering funds from employees who failed to provide adequate support demonstrating a business purpose for their travel.

California Department of Veterans Affairs

The California Department of Veterans Affairs made an economically wasteful decision when one of its veterans homes purchased furniture and stored it outside, exposed to the elements for an extended period, causing it to be no longer serviceable. Specifically, the veterans home stored new mattresses outside for about six months and stored new bed frames outside for over four years. The cost of the damaged furniture was approximately $23,500.

Multiple State Agencies

A manager who worked at various state agencies violated state law and engaged in gross misconduct by operating a personal business in which he coached prospective state employees on how to improperly obtain state employment. The manager’s misconduct led to his clients receiving unlawful appointments to state positions at various state agencies. Moreover, the manager utilized the methods he promoted in his business to unlawfully obtain state positions for himself.

Department of General Services

A custodian supervisor and two building managers at the Department of General Services engaged in improper hiring practices, including hiring family members and providing special assistance to their acquaintances during the hiring process.

California Department of Social Services

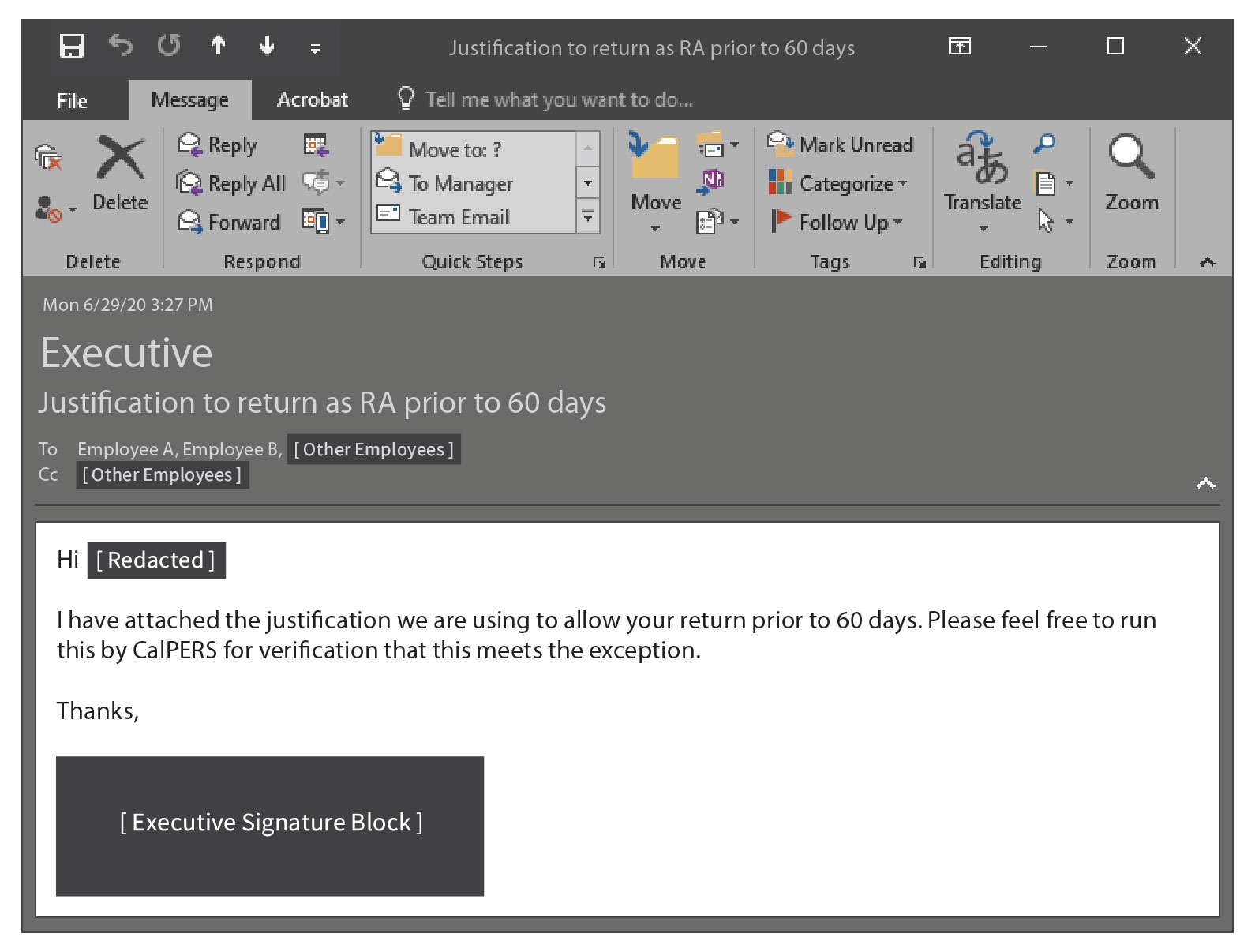

Two employees retired from the California Department of Social Services (Social Services) before they reached their normal retirement age, which made them subject to special requirements governing when and how they were allowed to return to state service as retired annuitants. However, before their official retirement dates from Social Services, each made an agreement with a department executive to return to work for Social Services after retirement. These agreements violated state laws that prohibit hiring prearrangements for employees who retire before reaching their normal retirement age.

Unnamed State Agency

A chief information security officer improperly disclosed personal information about multiple candidates for a student assistant position to another candidate for the position. The personal information included employment histories, dates of birth, addresses, and partial social security numbers for the other candidates. We are not naming the agency that is the subject of this report because doing so may identify or lead to the identification of the individuals mentioned in the report, which would violate state law.

California Department of Education

The California Department of Education (Education) does not conduct on-site reviews of nonpublic agencies as required by state law, despite collecting $1.6 million for the 2024 calendar year from nonpublic agencies to do so, nor does it have an established process to monitor nonpublic agencies. Education’s on-site reviews are intended to ensure that nonpublic agencies are appropriately providing alternative special education services to students with exceptional needs.

Introduction

Under the California Whistleblower Protection Act (Whistleblower Act), anyone who in good faith reports an improper governmental activity is a whistleblower and is protected from retaliation.1 An improper governmental activity is any action by a state agency or by a state employee performing official duties that does any of the following:

- Violates a state or federal law.

- Is economically wasteful.

- Involves gross misconduct, incompetence, or inefficiency.

- Does not comply with the State Administrative Manual, the State Contracting Manual, an executive order of the Governor, or a California Rule of Court.

Whistleblowers are critical to ensuring government accountability and public safety. The State Auditor protects the identities of whistleblowers and witnesses to the maximum extent required by law. Retaliation against state employees who file reports is unlawful and may result in monetary penalties and imprisonment.

Ways That Whistleblowers Can Report Improper Governmental Activities

Individuals can report suspected improper governmental activities through the toll‑free Whistleblower Hotline at (800) 952-5665, by U.S. mail, or through our website at www.auditor.ca.gov/whistleblower.

Investigation of Whistleblower Allegations

The Whistleblower Act authorizes our office, as the recipient of whistleblower allegations, to investigate and, when appropriate, report on substantiated improper governmental activity by state agencies and state employees. We may conduct investigations independently, or we may request assistance from other state agencies to perform confidential investigations under our supervision.

From January 2023 through December 2023, we conducted investigative work on 1,306 cases, some of which we received in previous periods. As Figure 1 shows, 859 of the 1,306 cases lacked sufficient information for investigation or were pending preliminary review. For another 402 cases, we conducted work or will conduct additional work—such as analyzing available evidence, contacting witnesses, and requesting information from state agencies—to assess the allegations. We referred another 13 cases to the relevant agencies so they could investigate the matters further, and we independently investigated or performed follow-up work on implementing recommendations for another 32 cases.

Figure 1

Status of 1,306 Cases, January 2023 Through December 2023

Figure 1 shows a pie chart of the disposition of the 1,306 cases that the investigations division staff worked on during calendar year 2023. 859 of 1,306 cases, or 66 percent, lacked sufficient information for an investigation or were pending review. Staff conducted or will conduct predication effort to assess allegations for 402 of 1,306 cases, or 31 percent. 13 of 1,306 cases, or one percent, were referred to another agency for investigation. Staff performed investigative or follow-up work for investigations for the remaining 32 of 1,306 cases, or two percent. The source of this information is the California State Auditor.

Source: State Auditor.

* Predication is reasonable cause to investigate an allegation. Establishing predication generally includes analyzing available evidence, contacting witnesses, and requesting information from state agencies.

Under the Whistleblower Act, the State Auditor may issue public reports when investigations substantiate improper governmental activities. When issuing public reports, the State Auditor must keep confidential the identities of the whistleblowers, any employees involved, and any individuals providing information in confidence to further the investigations. In this report, we may have changed how we refer to the gender of individuals involved in our investigations to protect their identities.

The State Auditor may also issue nonpublic reports to the head of the agencies involved and, if appropriate, to the Office of the Attorney General, the Legislature, relevant policy committees, and any other authority the State Auditor deems proper. The State Auditor cannot release the identities of the whistleblowers or any individuals providing information in confidence to further the investigations without those individuals’ express permission.

The State Auditor performs no enforcement functions: this responsibility lies with the appropriate state agencies, which are required to regularly notify the State Auditor of any actions they take in response to the investigations, including disciplinary actions, until they complete their final actions.

Chapter 1—Waste and Inefficiency

Department of Health Care Services

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

California Department of Veterans Affairs

Department of Health Care Services

A Supervisor Failed to Deposit a Check for Nearly $875,000, Resulting in Waste and Inefficiency

CASE I2023-11492

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that state agencies, including the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services), were failing to promptly deposit checks issued by the County of Los Angeles (LA County), we initiated an investigation.

About the Agency

Health Care Services provides Californians with access to quality health care and is the single state agency responsible for financing and administering the State’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, which provides health care services to low-income persons and families who meet defined eligibility requirements.

Our investigation determined that in June 2022, an accounting supervisor with Health Care Services failed to deposit a check for nearly $875,000 from LA County, resulting in waste and inefficiency.

Background

LA County, like many other counties, regularly publishes on its website all uncashed checks it has issued. We initially contacted Health Care Services in October 2023 and asked why it had not deposited a check in the amount of $874,707 issued in June 2022. Health Care Services explained that it reviewed all of the internal controls it had in place—including all received check images and tracking logs—and found no evidence that it had ever received the check in question. Given the high value of the check, we initiated an investigation to determine whether an improper activity occurred.

To provide a uniform approach to statewide policies regarding the management of the State, the State Administrative Manual (SAM) establishes the statewide policies, procedures, requirements, and information regarding a number of topics, including financial accounting. For example, SAM section 8022 requires that all checks received by state agencies be properly documented, and section 8032.1 requires that state departments deposit checks in a timely and economical manner, defined as within no more than five working days. Finally, Government Code section 8547.2 provides that any activity by a state employee that is economically wasteful or involves inefficiency is considered an improper governmental activity.

An Accounting Supervisor Failed to Promptly Deposit a Check in the Amount of Nearly $875,000

As shown in Figure 2, LA County contacted Health Care Services in December 2021 to ask about a missing check in the amount of $874,707. After verifying with Health Care Services that the check had not been cashed, LA County submitted a request to Health Care Services to reissue the missing reimbursement. In February 2022, Health Care Services issued a new check to LA County that included the reissuance of the missing $874,707. However, for reasons that Health Care Services could not explain, Health Care Services issued another check the following month for the missing $874,707. LA County deposited both checks.

Figure 2

Timeline of Events

Figure 2 provides a timeline of events from December 2021 through May 2023 between Health Care Services and LA County. In December 2021, LA County submitted a request for Health Care Services to reissue a missing check in the amount of $874,707. In February 2022, Health Care Services issues a check to LA County that includes the missing $874,707. In March 2022, Health Care Services issues a second check to LA County that includes the $874,707. LA County notifies Health Care Services of the duplicate payment and Health Care Services provides instructions to LA County on how to return the funds. On June 13, 2022, LA County issues a check refunding Health Care Services for a duplicate payment of $874,707. On June 21, 2022, Health Care Services’ accounting supervisor receives LA County’s check and requests additional details from Health Care Services’ program staff. On June 22, 2022, program staff contacts LA County and requests additional details to facilitate the proper deposit of the check. Program staff forwards information provided by LA County, but the accounting supervisor notifies program staff that additional information is still needed. On June 23, 2022, program staff contacts LA County again for additional details and forwards information to the accounting supervisor indicating that there is no additional information the program can provide. In May 2023, LA County notifies Health Care Services that its check remains uncashed. Health Care Services submits to LA County a request for reissuance. The source of this information is Health Care Services’ correspondence with LA County.

Source: Health Care Services’ correspondence with LA County.

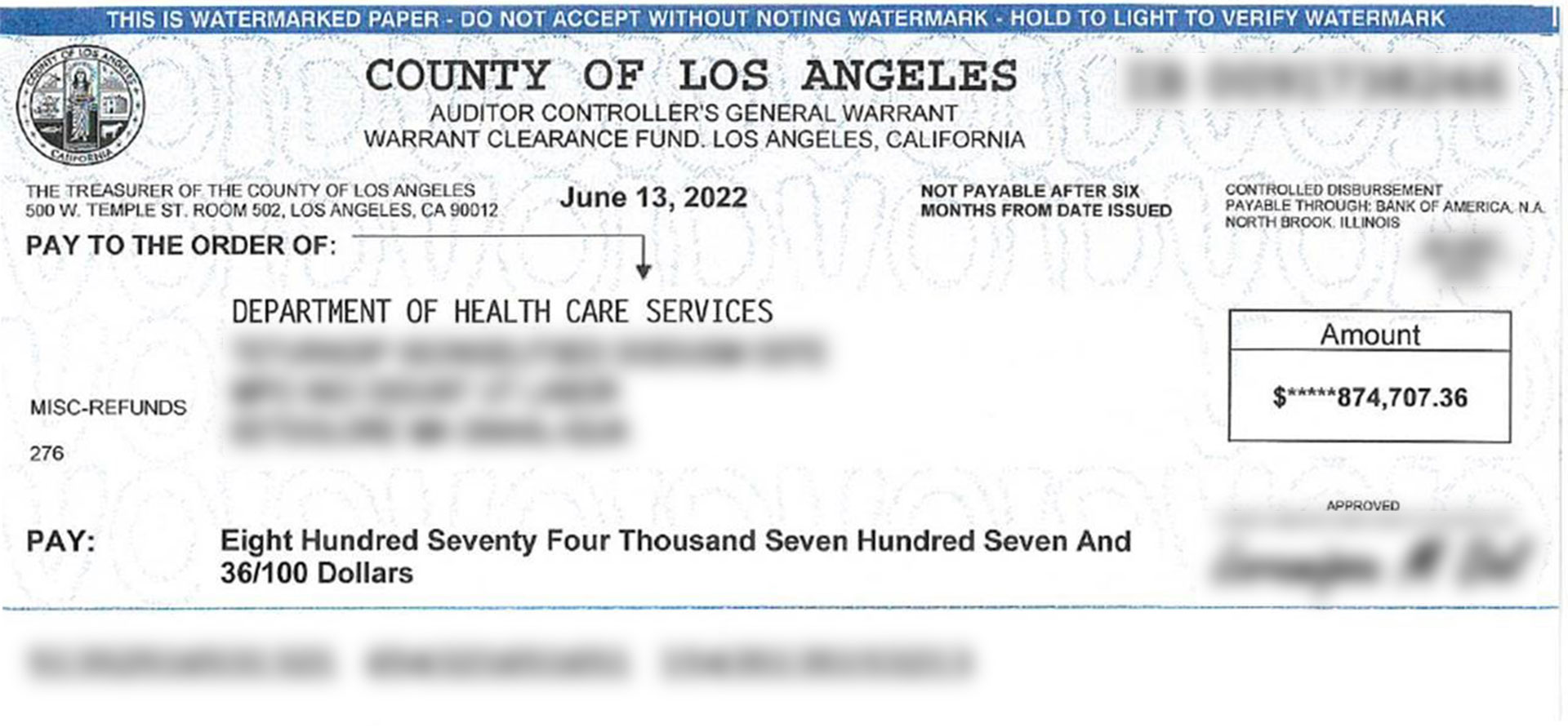

After recognizing that the March 2022 check was a duplicate payment, LA County informed Health Care Services’ program staff of the duplicate payment and requested instruction on how to refund the money.2 Program staff consulted with accounting staff, including an accounting supervisor, and then provided LA County with the needed instructions. On June 21, 2022, the accounting supervisor sent an email to accounting staff, acknowledging that he had received the refund check from LA County for $874,707. The email included a scanned copy of the check, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Uncashed Check From LA County

Figure 3 displays an image of the uncashed check from the County of Los Angeles, Auditor Controller’s General Warrant, Warrant Clearance Fund, Los Angeles California. The date on the check is June 13, 2022 and it is paid to the order of Department of Health Care Services in the amount of $874,707.36. Confidential information including the recipients address, approval signature, and bank account information are blurred out. The source of this information is Health Care Services.

Source: Health Care Services.

To correctly deposit the returned funds, Health Care Services accounting staff determined that they still needed additional information. Accompanying the check was an explanatory memo from LA County, along with copies of both state-issued checks and a breakdown of how the refund amount was calculated. At that time, the accounting supervisor asked program staff to provide his accounting unit with a check deposit memorandum to assist in depositing the check. In response to the accounting supervisor’s request, program staff reached out to LA County multiple times over the next two days to obtain additional information. By June 23, 2022, program staff explained to the accounting supervisor that $246,828 of the $874,707 was intended for the program and the remaining was intended for Medi-Cal adjustments. For that portion, program staff also provided the accounting supervisor with the needed funding ratio.

Ultimately, Health Care Services never deposited the $874,707 refund from LA County, and we could not find any evidence that any additional actions occurred before May 2023, when LA County contacted Health Care Services to notify it of the uncashed check. In response, Health Care Services submitted a request through the auditor-controller’s office for LA County to send yet another check for $874,707.

The Accounting Supervisor’s Actions Resulted in Waste and Inefficiency

The accounting supervisor’s failure to promptly deposit the check violated state policy and was economically wasteful, depriving the State from using the $874,707 for other departmental needs over the last two years. Had our office not received and investigated the complaint, Health Care Services would likely not have followed up on the unclaimed check and could have forfeited the opportunity to recoup the funds. Fortunately, at the time of our investigation, Health Care Services was still within the time frame to reclaim the funds from LA County by filing a request through the county’s auditor-controller’s office.

Our investigation also concluded that the accounting supervisor’s failure to deposit the check was inefficient. In our interview with the supervisor, we asked why he was unable to use the information provided with the two replacement checks issued by Health Care Services in February and March 2022 and work backward to properly account for the returned check. The accounting supervisor stated that his unit did not have access in June 2022 to all the information needed to deposit returned checks, but he admitted that another unit did and that he should have reached out to the other unit.

Further, our investigation found that Health Care Services failed to follow its internal controls over deposits. Specifically, neither the accounting supervisor nor any other accounting staff properly logged the refund check from LA County after Health Care Services received it. This is in conflict with the state requirement that all received checks be documented and with Health Care Services’ policy that each check be scanned and logged. When we asked the accounting supervisor for assistance in locating the check, he could not find any record of it and speculated that the check might have been returned to the sender because of a lack of information. After we showed him copies of the emails he had sent in June 2022, confirming that he had personally received the check, he concluded that the check had likely been lost. He noted that when he received the check, he was still trying to learn his role as supervisor, which he had held for about a year, and he agreed that he may have lost track of the check.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, Health Care Services should take the following actions:

- Ensure that Health Care Services ultimately deposits the $874,707 refunded by LA County.

- Determine why duplicate payments were issued in February 2022 and March 2022 and why the department’s internal controls did not prevent or detect this overpayment.

- Provide the accounting supervisor and his staff with training on how to properly document and deposit each received check, including refresher training on the proper logging and scanning of checks awaiting deposit.

- Develop written procedures defining the actions staff must take when checks arrive without sufficient documentation.

- Develop and implement a mechanism for assessing, at regular intervals, whether Health Care Services’ new controls and policies are being followed.

Agency Response

In August 2024, Health Care Services reported that it has taken prompt measures to implement our five recommendations. Regarding our first recommendation, Health Care Services reported that it had recently routed to LA County a new claim for the missing check with an affidavit attesting that a duplicate payment is needed.

In response to our second recommendation, Health Care Services explained that it had found that the duplicate payments initially made to LA County in 2022 were caused by duplicative payment requests generated within Health Care Services. To prevent this from recurring, Health Care Services plans to review its internal control processes and identify any gaps in the process.

To our third recommendation, Health Care Services stated that the accounting supervisor and his staff will receive training and that it will send written reminders of the proper procedures on a monthly basis. Moreover, Health Care Services stated that as part of its onboarding process, it plans to train new staff on how to properly document each received check.

In response to our fourth recommendation, Health Care Services provided evidence that it had recently established and disseminated new written procedures to the appropriate staff. The new procedures require that all unidentified checks be batched as miscellaneous revenue and processed within three to five business days; checks greater than $10,000 are required to be processed within 24 hours.

Regarding our fifth recommendation, Health Care Services stated that its new procedures created in response to the fourth recommendation require a manager to review check logs and daily deposit logs on a weekly basis to ensure compliance with the new procedures. Health Care Services also stated that the manager will present a monthly compliance update to its branch and division chiefs and that it will train its staff again if the manager identifies any noncompliance.

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

It Did Not Follow an Efficient Process to Collect Employees’ Travel Claims

CASE I2024-09196

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

As of April 2024, nearly 150 current and former employees incurred more than $92,000 for unsupported travel expenses that occurred before 2024. These expenses included charges such as airfare and rental cars and were paid for directly by the department. The employees subsequently did not submit any justification for the expenses. California Department of Tax and Fee Administration’s (CDTFA) delay in identifying travel expenses that lacked support prevented it from efficiently recovering funds from employees who failed to provide adequate documentation demonstrating a business purpose for their travel expenditures. In response to an allegation involving unsupported travel expenses, we initiated an investigation.

About the Agency

CDTFA administers California’s sales and use, fuel, tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis taxes, along with other taxes and fees that fund specific state programs. CDTFA collects more than $90 billion annually, which supports local services such as transportation, public safety, and health. To serve customers, CDTFA has offices located throughout California as well as in New York, Chicago, and Houston.

CDTFA’s Travel Unit Did Not Promptly Identify Unsupported Travel Expenses

The State generally pays for travel expenses when employees travel for business purposes. In order to support state-paid travel expenses, employees must submit a travel expense claim or explanation to their supervisor for approval that provides the justification for the trip and expenses, and they must include supporting receipts when appropriate. California Department of Human Resources’ rules require that travel claims contain a brief statement of purpose for each trip, and California Code of Regulations requires receipts for each expense of $25 or more. In addition, Government Code section 13401 identifies as state policy a requirement that each state agency maintain effective systems of internal controls to minimize fraud, errors, abuse, or waste of government funds. By consistently and promptly collecting travel expense claims after travel is completed, officials who approve claims are well‑positioned to review the justification for claimed expenses.

CDTFA officials explained that when there is a need for employees to travel, the employees notify their supervisor before traveling and make the necessary travel reservations such as booking a flight or reserving a rental car. These travel costs are paid directly by the department. CDTFA policy requires the employees to submit travel expense claims to their supervisor for approval within 10 days of travel completion. The supervisor then verifies that the travel was work‑related and sends the approved claims to accounting staff for processing. However, as of April 2024, travel expenses totaling $92,166 from nearly 150 employees throughout CDTFA and the Board of Equalization (BOE) still lacked evidence to support the business purpose of the travel occurring before 2024.3 These expenses—including lodging, airfare, and transportation—were charged to the State, but employees have not produced documentation to support the business purpose of the expense. The delayed processing of these expenses is inefficient, and Government Code section 8547.2 identifies inefficiency as an improper governmental activity. Further, Government Code section 8314 prohibits state officials from using public resources for personal purposes, and in the absence of supporting documentation, CDTFA has no evidence that these expenses were for work‑related travel.

We also found that CDTFA did not maintain an effective system of controls to provide oversight. Staff within CDTFA’s travel unit were confused about their responsibility to reconcile travel charges. An official with responsibility to provide oversight of the travel unit reported that the unit lacked an effective process to reconcile charges against travel expense claims and to follow up with employees. Another official who also had oversight of the travel unit asserted that there had been a process in place in the past, but she admitted that the travel unit had not reconciled charges against travel claims for at least three or four years. She also reported that when she discussed this with the two supervisors who have direct oversight of the travel unit, the supervisors were not even aware that their unit needed to perform this function. Both oversight officials explained that CDTFA is attempting to develop and document a reconciliation process whereby travel unit staff reconcile travel charges against expense claims on a monthly basis to ensure that employees submit an appropriate travel claim for the charges.

CDTFA’s delay in identifying unsupported travel expenses made it difficult to collect evidence on the business purpose of trips and to recoup the travel charges from employees who could not demonstrate a business purpose associated with the travel. Because the travel unit did not identify unsupported travel expenses in a timely manner, the travel unit eventually asked some former employees to submit documentation to support the business purposes of trips they had taken several years earlier while still employed with the agency. When employees leave the agency or retire from state service, they typically do not have access to supporting evidence such as agency emails, calendars, and travel reservations to research the business purpose of their past trips, which makes it more difficult to obtain supporting information. Additionally, even if an employee is able to submit documentation to support a business purpose for the expense, by not doing so within the required 10‑day period, individuals who approve the claim may not have the information on hand to properly evaluate it.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, CDTFA should take the following actions:

- Finalize, document, and implement a reconciliation process that involves comparing travel charges against travel expense claims to promptly identify unsupported travel expenses, and identify appropriate staff who will complete this reconciliation following any necessary training.

- Implement a specific plan to resolve unsupported travel expenses incurred before 2024.

Agency Response

CDTFA reported that as of September 2024, employees have submitted documentation to support the business purpose of approximately $45,000 of the travel expenses and that it expects to resolve the remaining unsupported travel expenses by June 2025. CDTFA clarified that although it processes BOE’s travel claims, it does not have supervisory oversight of BOE employees, but it will work with BOE management to implement necessary protocols.

CDTFA also reported that its travel team now sends monthly updates regarding unsupported travel expenses directly to CDTFA program leaders and BOE management to ensure that they are addressed timely. Finally, to provide context, CDTFA explained that its travel expense unit has experienced retention challenges while processing an increasing number of travel claims.

California Department of Veterans Affairs

Staff Wasted State Funds by Purchasing Mattresses and Bed Frames and Leaving Them Outside for an Extended Period

CASE I2023-0364

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that the California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet) purchased mattresses and bed frames and stored many of the purchases outside for an extended period, rendering some of the furniture damaged or unusable, we initiated an investigation.

About the Agency

CalVet oversees eight veterans homes across the State. The homes offer affordable long-term care to aged and disabled veterans as well as their eligible spouses and domestic partners and provide services ranging from independent living programs with minimal support to 24/7 skilled nursing care for veterans with significant clinical needs.

Our investigation determined that CalVet made an economically wasteful decision when one of its homes purchased furniture and stored it outside. In 2022, the home disposed of at least 17 unused mattresses that it bought in 2021 and stored outside, exposed to the elements. The resulting waste cost the State more than $3,500. Further, at the time of our investigation, the home continued to store outside 13 bed frames that it purchased in 2020, which may result in additional waste of more than $20,000.

The Home Disposed of at Least 17 Unused Mattresses, Resulting in Waste

In November 2021, at the request of a supervising nurse at the veterans home, CalVet purchased 150 mattresses—costing more than $200 a piece—to replace old and worn out mattresses for residents in the skilled nursing unit at the home. However, the home disposed of at least 17 of those mattresses before they were ever used because they were stored outside for an extended period and became damaged from exposure to the elements. Witnesses informed us that it was possible that the mattresses were stored outside because the home did not have enough indoor storage space. Most of the new mattresses were kept outside until they were needed by residents or until appropriate indoor storage space became available. During the summer of 2022, during a major “clear out” of the home’s equipment and furniture, a witness confirmed that the home distributed the useable mattresses to various units within the home or storage rooms and disposed of any damaged yet unused mattresses. Although a witness said the home disposed of maybe 30 to 40 damaged and unused mattresses, we were only able to find documentation verifying that the home disposed of 17 mattresses. As a result, the home wasted at least $3,400 and engaged in an improper governmental activity, as defined by Government Code section 8547.2.

The Home Continued to Store 13 Bed Frames Outside, Which May Result in Additional Waste

In 2020, at the request of the supervising nurse, CalVet purchased 15 specialized bed frames, at $1,561 each, for its fall-risk residents at the home. As of February 2024, the home had not put the bed frames into service and was storing 13 of them outside, exposed to the elements. After receiving the 15 bed frames, staff at the home learned that the bed frames were unusable because they did not include necessary parts, including bed rails that would keep residents safe in their beds. A witness informed us that staff at the home ordered the bed frames without knowing that they were incomplete and needed additional parts. A witness explained that staff requested that CalVet order the bed parts in 2021 and 2022, but the requests were denied because the funds were redirected to higher-need projects. The witness confirmed that in September 2023, nearly three years after the purchase of the bed frames, the home ordered the needed parts; however, three of the seven parts needed for each bed frame were on back order without an estimated time of arrival. In the meantime, the home continued to store the bed frames outside, exposed to the elements and deteriorating since 2020.

It remains unclear whether the home will be able to use these bed frames when the missing parts eventually arrive. A witness confirmed to us that the bed frames have started to rust during their exposure to the weather. Ultimately, CalVet’s purchase and improper storage of the bed frames it did not promptly use may result in waste that costs the State approximately $20,000 to $23,000.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, CalVet should take the following actions:

- Cover any furniture that is currently stored outside, exposed to the elements, or move that furniture indoors.

- Create and distribute a policy that prohibits the practice of storing furniture outside. The policy should prohibit CalVet’s procurement of furniture unless the home has sufficient space to safely store it until it is put into service.

- Determine whether the bed frames are serviceable or can be refurbished. If they are, make additional efforts to obtain the parts needed to put the bed frames into service.

Agency Response

In August 2024, CalVet reported that it had reviewed our report, concurred with our recommendations, and had begun taking steps to implement them. In response to our first recommendation, CalVet reported that the home is no longer storing the mattresses and bed frames outside. Further, it stated that its audit chief completed an on-site inspection of the home and accounted for the 150 mattresses and 15 bed frames. It said that several of the remaining mattresses are now being used by the residents. CalVet acknowledged that the home had inadequate storage space at the time it purchased the furniture; therefore, by December 2024, it plans to purchase storage containers for the necessary supply of mattresses and beds it must keep on hand.

Regarding our second recommendation, CalVet plans to create and implement a policy by December 2024 that will address the importance of properly storing furniture and procuring an appropriate amount of furniture that is readily deployable.

In response to our third recommendation, CalVet stated that it has communicated with the vendor and awaits the beds’ last missing part, which continues to be on back order. CalVet said that once it receives the remaining part, its home maintenance team will assemble the 15 beds, and the director of nursing will then inspect the assembled beds to confirm whether they are functional and can be used safely.

Chapter 2—Improper Hiring

Department of General Services

California Department of Social Services

Multiple State Agencies

A Manager’s Gross Misconduct Resulted in Numerous Unlawful Appointments

CASE I2023-1220

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that a manager was charging clients for classes on “how to get a state job” and teaching them to falsify their exams and qualifications, we initiated an investigation.

Our investigation determined that since at least 2021, a manager who worked at various state agencies violated state law and engaged in gross misconduct by operating a personal business in which he coached prospective state employees on how to improperly obtain state employment. For example, he coached prospective state employees on the answers they should provide while taking online state examinations, and he coached employees to embellish or falsify their qualifications when applying for state jobs. The manager’s misconduct led to his clients receiving unlawful appointments to state positions at various state agencies. Moreover, the manager used the methods he promoted in his business to unlawfully obtain state positions for himself.

Background

Since California established merit-based hiring with the passage of the Civil Service Act in 1934, state law has mandated that appointments to state jobs be based on merit and reserved for those who possess the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities.

In order for a qualified candidate to be selected, California requires candidates to act in good faith. California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 243, subdivision (c), provides that an appointment is made in good faith when candidates provide complete, factual, and accurate information during the recruitment process. Moreover, for a good-faith appointment, candidates are required to truthfully and honestly answer all questions related to experience, education, and level of competency. By contrast, a person who does not provide accurate information during the recruitment process could be considered to act in bad faith, which could lead to an unlawful appointment. California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 243.3 provides that candidates who do not act in good faith and subsequently have appointments voided may be required to reimburse the State all, or a portion of, the compensation resulting from the appointment.

One of the widely used classifications in state government is the associate governmental program analyst (AGPA) classification. This classification typically requires that candidates take an online exam that asks questions related to education and experience to measure whether the candidates meet the established requirements for the classification. Performing well on the exam indicates to hiring managers that a candidate meets the qualifications for the classification and allows candidates to be placed on a list of candidates from which hiring managers can select eligible individuals. If a candidate is not placed on a list of eligible candidates, state agencies are not able to hire the candidate.

In addition, the Whistleblower Act states that improper governmental activity may include gross misconduct committed by a state employee. For the purposes of this report, gross misconduct is interpreted to mean unacceptable behavior of the sort that typically results in dismissal of the offending employee.

A Manager Engaged in Gross Misconduct When He Advised Paid Clients on How to Fraudulently Obtain State Positions

For approximately 20 years, the manager operated a personal business helping individuals obtain state employment. The manager accepted clients by referrals only and helped them acquire state jobs, typically into the AGPA classification. The manager provided a range of services to help clients obtain state employment, typically charging between $500 and $600 for his services, including the following:

- Exam guidance.

- Assistance with résumés, cover letters, state employment applications, and statements of qualifications (SOQs).

- In-person interview practice.

- Assistance with portfolios of employment-related documents.

The manager hosted in-person classes at his home on weekends, sometimes multiple times a month, during which he provided improper assistance to his clients. Witnesses told us that during the classes, the manager had his clients take the AGPA online exam together, and he instructed them to mark specific answers to ensure they obtained the highest score. One witness told us that when a participant fell behind the rest of the class, the manager marked the answer for the participant on the participant’s personal computer. This violated Government Code section 19680, which prohibits any individuals from willfully furnishing any special or secret information to any person for the purpose of improving their prospects during an examination for a state position. Further, section 19681 prohibits any person from obtaining, except by specific authorization, examination information before, during, or after an exam for the purpose of instructing or coaching or preparing candidates for examinations. A person violating either section is guilty of a misdemeanor, as stated in section 19682. California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 178, also states that competitors are forbidden to receive any unauthorized assistance in state examinations.

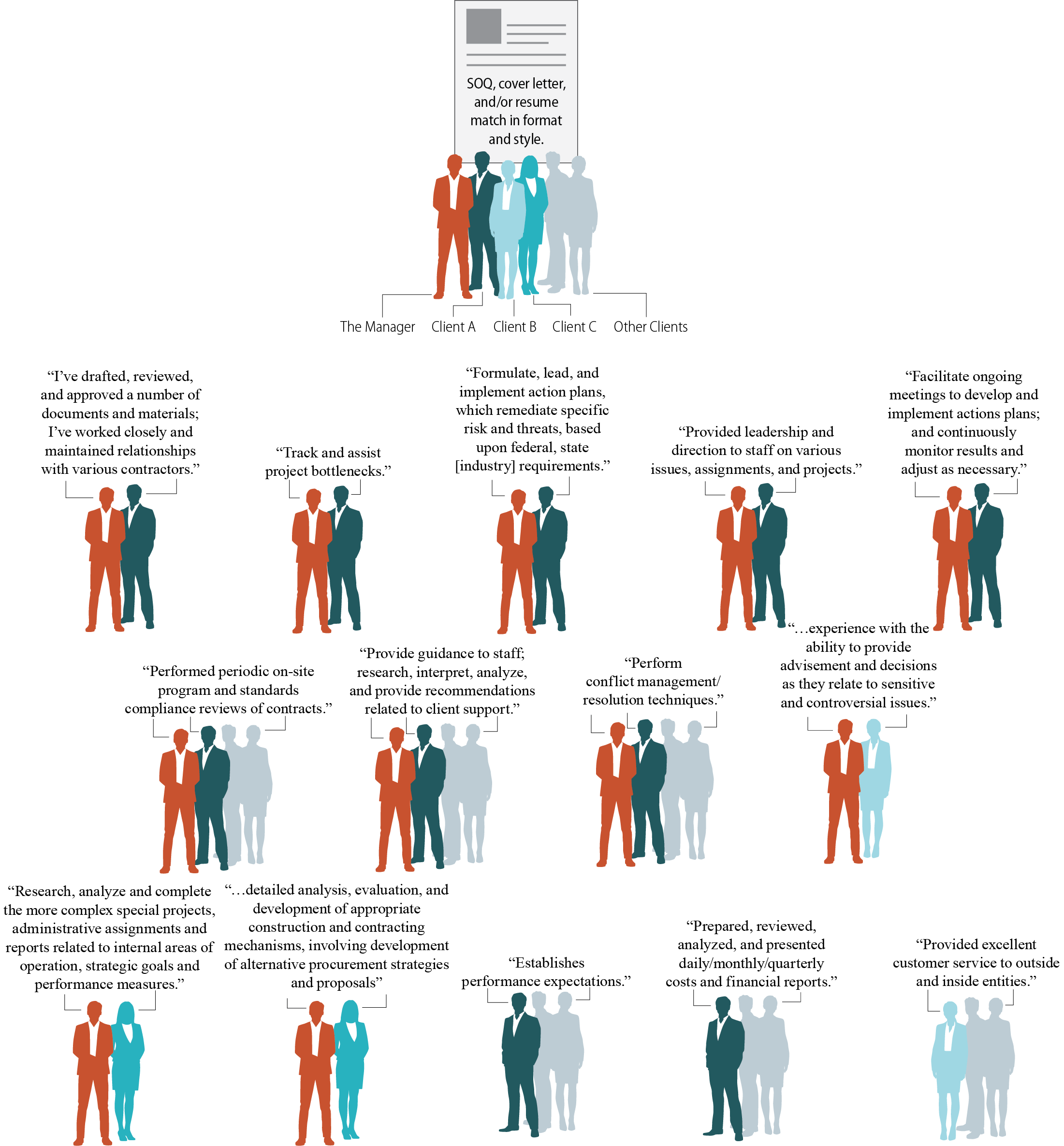

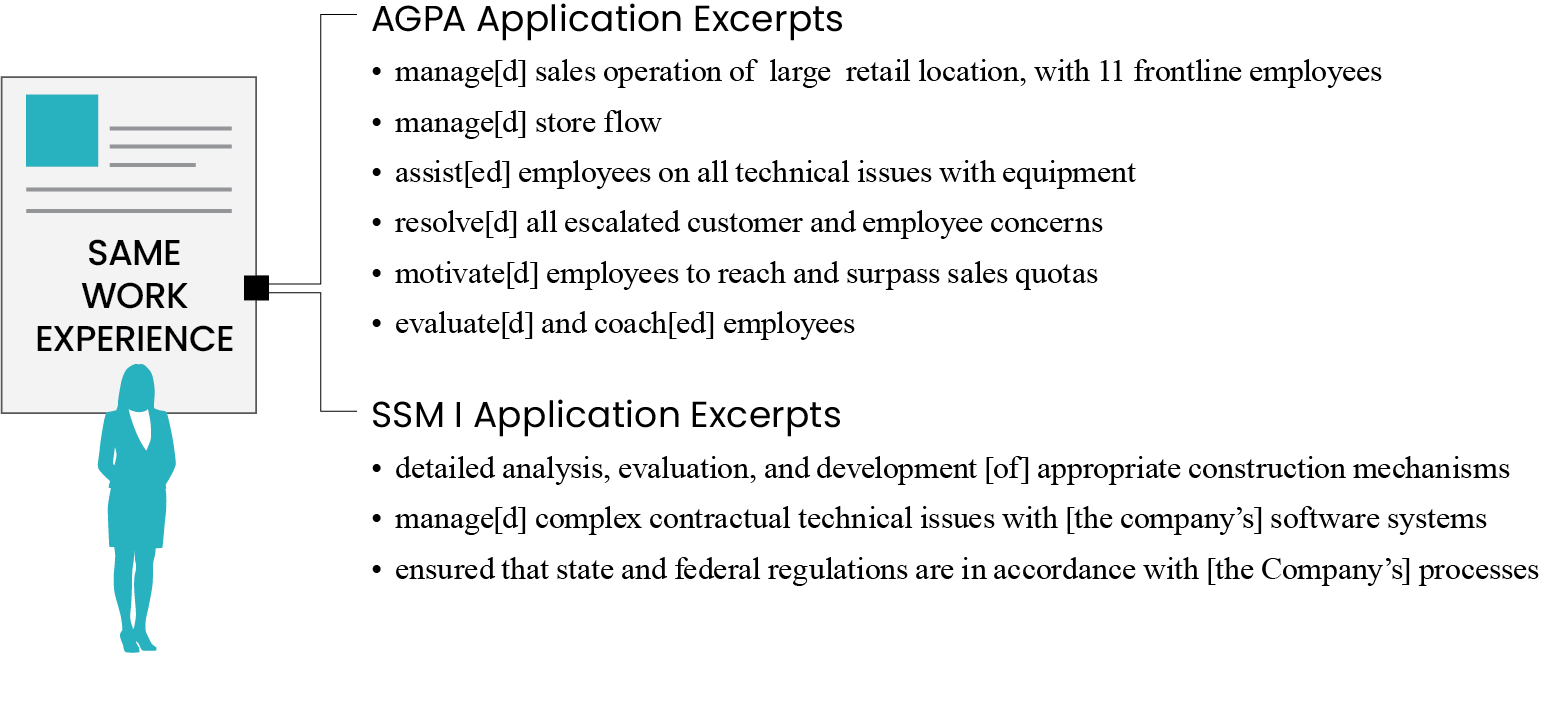

Witnesses also told us that the manager encouraged clients to lie about their work experience on their state employment applications. Specifically, during the in‑person classes, the manager coached attendees to provide job descriptions that embellished and misrepresented their qualifications and past positions. The manager requested that his clients send him their cover letters and résumés via email and then he would instruct the individuals to plagiarize and incorporate into their own documents information from samples that he provided. His written instructions to his clients included coaching to “copy word-for-word” from his samples. Figure 4 provides several examples of verbatim or near-verbatim content we found among the application documents of the manager’s clients. Although the manager had many clients over the years, this investigation focused on the manager and three of his clients and took into account information regarding a few of his other clients as well.

Figure 4

Examples of Verbatim or Near-Verbatim Content Across Documents From the Manager and His Clients

Figure 4 displays groupings of the manager and his clients with examples of verbatim or near-verbatim content across their documents. The first group includes the manager and Client A with the following examples: “I’ve drafted, reviewed, and approved a number of documents and materials; I’ve worked closely and maintained relationships with various contractors.” “Track and assist project bottlenecks.” “Formulate, lead, and implement action plans, which remediate specific risk and threats, based upon federal, state [industry] requirements.” “Provided leadership and direction to staff on various issues, assignments, and projects.” “Facilitate ongoing meetings to develop and implement actions plans; and continuously monitor results and adjust as necessary.” The second group includes the manager, Client A, and other clients with the following examples: “Performed periodic on‐site program and standards compliance reviews of contracts.” “Provide guidance to staff; research, interpret, analyze, and provide recommendations related to client support.” “Perform conflict management/resolution techniques.” The third group includes the manager and Client B with the following example: “…experience with the ability to provide advisement and decisions as they relate to sensitive and controversial issues.” The fourth group includes the manager and Client C with the following examples: “Research, analyze and complete the more complex special projects, administrative assignments and reports related to internal areas of operation, strategic goals and performance measures.” “…detailed analysis, evaluation, and development of appropriate construction and contracting mechanisms, involving development of alternative procurement strategies and proposals.” The fifth group includes the manager and other clients with the following examples: “Establishes performance expectations.” “Prepared, reviewed, analyzed, and presented daily/monthly/quarterly costs and financial reports.” The sixth group includes Client B and other clients with the following example: “Provided excellent customer service to outside and inside entities.” The source of this information is the investigator’s analysis of the manager’s and his clients’ state employment application documents.

Source: Investigator analysis of the manager’s and his clients’ state employment application documents.

One witness stated that the manager told the clients in the witness’s class that if they pass the six-month probation period, they could apply for higher-level positions even if they are not qualified for the positions. The witness said that the manager further stated that if they don’t succeed at the higher position, they would always maintain return rights to their original position. Moreover, the witness said that the manager told his clients that he had obtained managerial positions without the needed qualifications and that they could do likewise. Once clients had prepared their application documents to the manager’s satisfaction, he let them know that they could move forward and apply for open positions.

When we interviewed the manager, he said that he had been helping people obtain state jobs for more than 20 years. However, he denied advising his clients to misrepresent their work experience. When confronted with evidence that it was his advice that led his clients to include false information on their applications, the manager stated that he disagreed. When confronted with evidence showing sentences and content that are verbatim across his clients’ application documents and in his own applications, he said he couldn’t explain why they were so similar. He later stated that he simply made “recommendations” and that it was up to his clients to trust their own judgment on what they chose to put on their applications. When asked whether he instructed his clients to mark the same answers on the AGPA exam in order to get the highest scores, he stated that he did not and that it was up to his clients to answer the questions. The evidence we collected did not support the manager’s claims.

The Manager’s Guidance to Clients Resulted in Unlawful Appointments

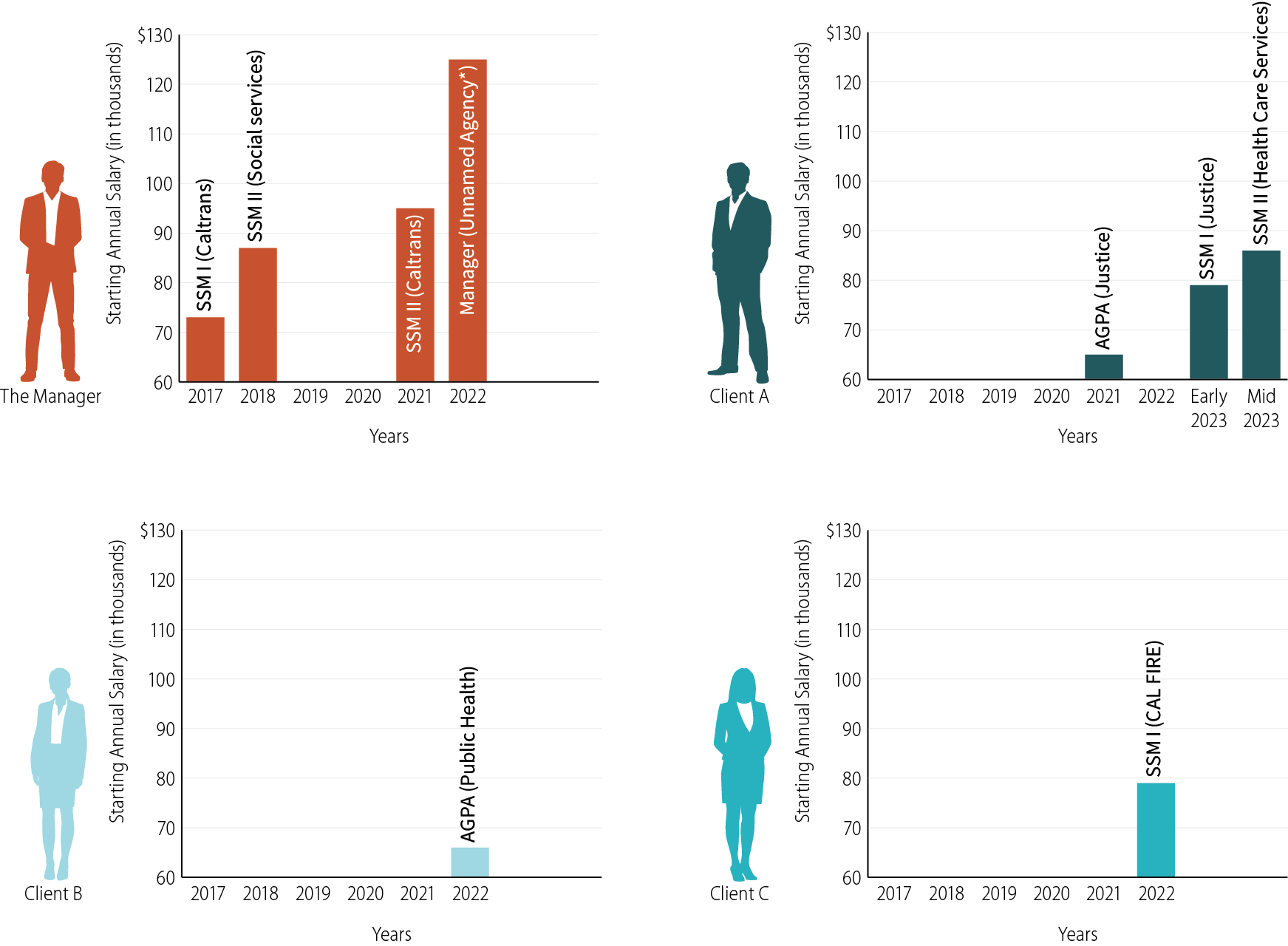

All four subjects of this investigation—the manager and three of his clients—held unlawful appointments in state service. Figure 5 presents the unlawful appointments discussed in this report.

Figure 5

Each Unlawful Appointment Discussed in This Report and the Applicable Starting Salary

Figure 5 shows four bar graphs of each unlawful appointment discussed in this report and the applicable starting salary. The four bar graphs show the unlawful appointments and starting salaries for the manager, Client A, Client B, and Client C, respectively. The bar graph for the manager shows that in 2017, he was appointed at Caltrans as an SSM I with a starting annual salary of approximately $73,000; in 2018, he was appointed at Social Services as an SSM II with a starting annual salary of approximately $87,000; in 2021, he was appointed at Caltrans as an SSM II with a starting annual salary of approximately $95,000; and in 2022, he was appointed at an unnamed agency as a manager with a starting annual salary of approximately $125,000. We are not naming the agency because doing so may identify or lead to the identification of the individuals mentioned in the report, which would violate Government Code section 8547.7, subdivision (c). The bar graph for Client A shows that in 2021, he was appointed as an AGPA at Justice with a starting annual salary of approximately $65,000; in 2023, he was appointed at Justice as an SSM I with a starting annual salary of approximately $79,000; and in 2023, he was appointed at Health Care Services as an SSM II with a starting annual salary of approximately $86,000. The bar graph for Client B shows that in 2022, she was appointed at Public Health as an AGPA with a starting annual salary of approximately $66,000. The bar graph for Client C shows that in 2022, she was appointed at CAL FIRE as an SSM I with a starting annual salary of approximately $79,000. The source of this information is the investigator’s analysis of the manager’s and his clients’ state employment and payment histories.

Source: Investigator analysis of the manager’s and his clients’ state employment and payment histories.

* We are not naming the agency because doing so may identify or lead to the identification of the individuals mentioned in the report, which would violate Government Code section 8547.7, subdivision (c).

Client A Was Dishonest on His State Exam and Employment Applications, Resulting in Three Unlawful Appointments

Client A procured the manager’s services in early 2021 for $500 after being referred by a friend who also used the manager’s services and is a current state employee. Although Client A initially denied providing false information on his application, Client A ultimately admitted that he did include false information on his state employment applications after the manager advised him to do so. Specifically, Client A admitted that the manager instructed him to select specific answers on the AGPA exam—answers we confirmed he selected on his exam—and that he submitted false information about his titles, dates of employment, and duties with several employers. Some of Client A’s misrepresentations in his initial AGPA application include the following:

- Operations General Manager—Client A indicated that he worked four and a half years as the “operations general manager” for a large gym in addition to working there another four years in lower positions. Although he did work for the gym, Client A admitted that he only worked there for a total of five and a half years and never as the operations general manager.

- Accounting Administrator—Client A claimed that he worked as an “accounting administrator” at a private company and that he prepared, reviewed, and analyzed financial reports, among other accounting-related duties. Client A admitted that he was instead the receptionist for the office, helping coordinate maintenance requests when tenants called.

- Accounting Specialist—Client A claimed to be an “accounting specialist” at an extermination company but later admitted that he did not perform the duties he listed. Rather, he sprayed pesticides for the company.

Client A stated that although he was hesitant to misrepresent his experience, he did so because the manager advised him to do so. Once he was hired with the Department of Justice (Justice) as an AGPA in 2021, Client A used much of the same false information from his AGPA application to obtain two subsequent promotions: In 2023, he was promoted as a staff services manager (SSM) I with Justice. A few months later, he was hired as an SSM II with Health Care Services. Client A was dishonest in all of his state employment applications, which means that he acted in bad faith. Therefore, California Code of Regulations, title 2, sections 243.2 and 243.3 allow for Client A’s appointments to be voided and for all or some of the compensation he received to be reimbursed to the State. During Client A’s career with the State, he had earned $233,508 as of June 2024. Less than a year after his promotion, Client A failed to pass probation at the SSM II level after his manager identified deficiencies in his knowledge, skills, and abilities for the position, and he returned to his prior SSM I position at Justice.

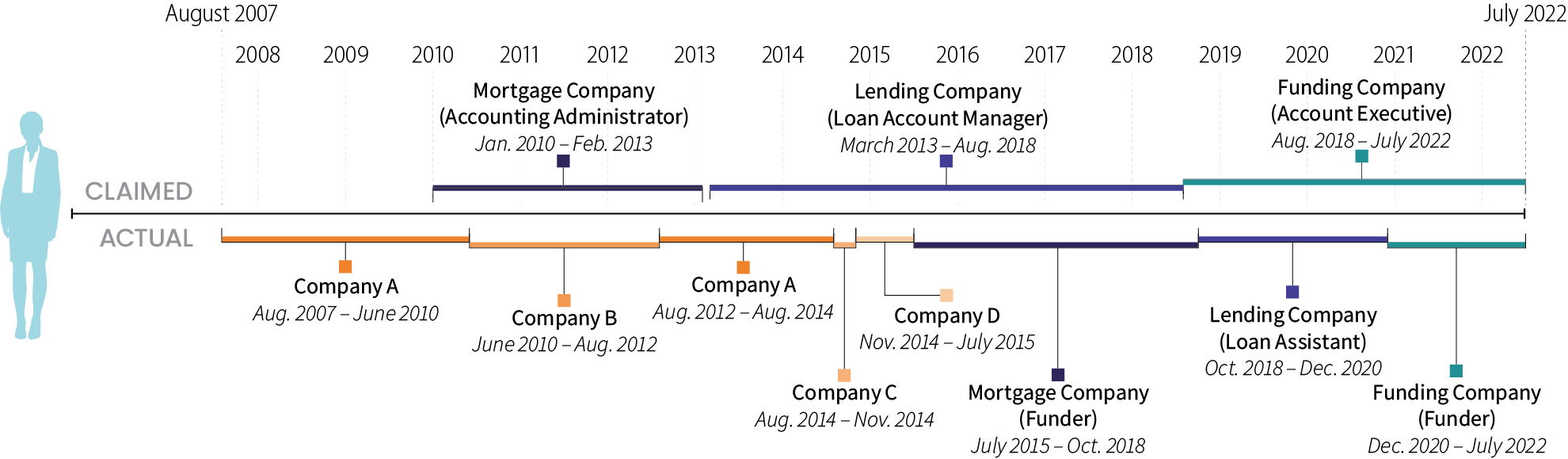

Client B Was Dishonest on Her State Employment Application, Resulting in an Unlawful Appointment

Client B paid the manager $600 in 2021 after being referred by a friend. In 2022, Client B was hired by the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) as an AGPA. During our interview, Client B admitted that she was not truthful on her job application and that the manager advised her to embellish her experience by using higher-level titles and by claiming longer employment durations at jobs than she actually worked, as shown in Figure 6. For example, on her application, Client B claimed to work for a lending company for five years as a loan account manager. However, Client B admitted that the claim was false and that she had only worked there for a little over two years, as a loan assistant, and during a different time span than she had listed on her application.

Figure 6

Client B’s Misrepresented Work Experience

Figure 6 depicts the difference between Client B’s claimed and actual work experiences from August 2007 through July 2022. Client B claimed that she worked at a mortgage company as an accounting administrator from January 2010 to February 2013; at a lending company as a loan account manager from March 2013 to August 2018; and at a funding company as an account executive from August 2018 to July 2022. However, she actually worked at Company A from August 2007 to June 2010; at Company B from June 2010 to August 2012; again at Company A from August 2012 to August 2014; at Company C from August 2014 to November 2014; and at Company D from November 2014 to July 2015. Further, she actually worked at a mortgage company as a funder from July 2015 to October 2018; at a lending company as a loan assistant from October 2018 to December 2020; and at a funding company as a funder from from December 2020 to July 2022. The source of this information is Client B’s state employment applications, LinkedIn profile, and interview statements.

Source: Client B’s state employment applications, LinkedIn profile, and interview statements.

Client B informed us that when she expressed concerns to the manager on misrepresenting her experience on her application, the manager told her that the State was not the FBI, implying that the State would not catch her misrepresentations. Client B was dishonest on her state employment application, which means that she acted in bad faith. Therefore, state law allows Client B’s appointment to AGPA to be voided and for all or some of the compensation she earned in this bad-faith appointment to be reimbursed to the State. During Client B’s time in the AGPA position with Public Health, she had earned $108,540 as of June 2024.

Client C Was Dishonest on Her State Employment Application, Resulting in an Unlawful Appointment

Client C enlisted the manager’s help after being referred by a friend. When Client C started looking for a promotion, she used the manager’s services but said she only paid $100. Ultimately, Client C was promoted to an SSM I position at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) in 2022. Unlike the other clients we interviewed, Client C stated that she never attended the in-person classes that the manager hosted and was instead coached over the telephone.

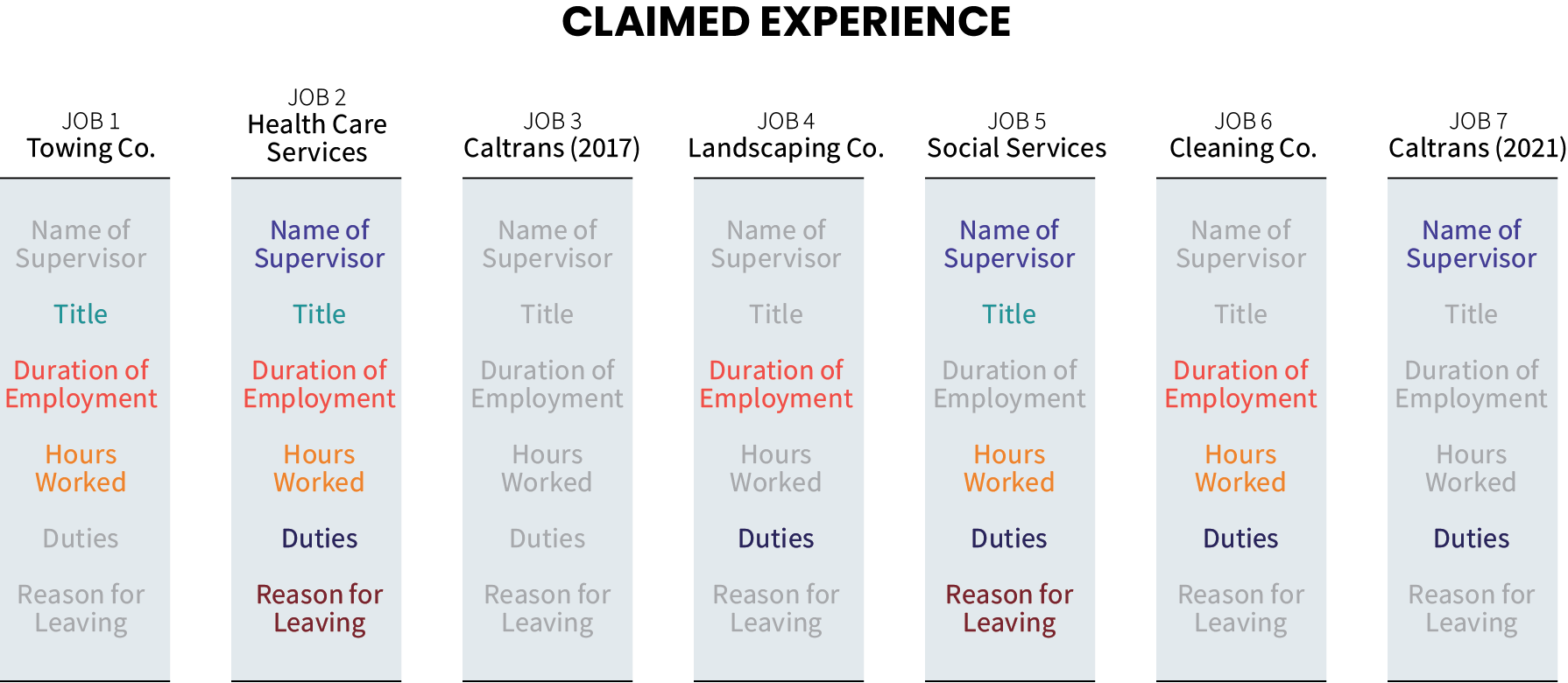

During our interview, Client C denied embellishing her work experience. However, the evidence we collected, in addition to the responses she provided in her interview, indicate that she provided false information on her SSM I application. Specifically, Client C claimed to work for a large cellular company for over ten years in a managerial capacity. However, when we reviewed Client C’s application for her first state job, we noted significant differences in how she portrayed the same experience. For example, on her SSM I application, she claimed to work as a customer service manager for more than eight years under one supervisor. In contrast, on her AGPA application, she stated that she worked as a retail sales representative for two years before shifting to a call center customer service supervisor for an additional six years. Two different supervisors were listed as her supervisors for these two positions. When asked why her title changed from supervisor to manager in the SSM I application, she stated that the two titles were the same for her. She added that she worked at a call center with 1,000 employees and that if another manager was out sick, she would manage all the employees. However, her AGPA application and her LinkedIn profile both state that as the call center customer service supervisor, she supervised only 13 or 14 employees in a call center with 450 representatives.

In addition, the experience Client C described when she applied for the SSM I position notably differed from the experience she described when she applied for the AGPA position in her two job applications. Figure 7 shows one example of how Client C characterized the same experience differently on the two different job applications. When we interviewed Client C, she admitted that the characterizations on her AGPA application, which also matches her LinkedIn profile, better represented her experience.

Figure 7

Client C’s Portrayal of the Same Work Experience on Two Different State Employment Applications

Figure 7 shows “Same Work Experience” in a text box above a human figure and provides a list of examples of how Client C characterized the same experience differently on the two different job applications. Client C’s AGPA application excerpts included: manage[d] sales operation of large retail location, with 11 frontline employees; manage[d] store flow; assist[ed] employees on all technical issues with equipment; resolve[d] all escalated customer and employee concerns; motivate[d] employees to reach and surpass sales quotas; and evaluate[d] and coach[ed] employees. Client C’s SSM I application excerpts included: detailed analysis, evaluation, and development [of] appropriate construction mechanisms; manage[d] complex contractual technical issues with [the company’s] software systems; and ensured that state and federal regulations are in accordance with [the Company’s] processes. The source of this information is Client’s C’s state employment applications.

Source: Client’s C’s state employment applications.

Client C was dishonest on her state employment application, meaning that she acted in bad faith. Therefore, state law allows for Client C’s appointment to the SSM I position to be voided and for all or a portion of the compensation she earned in this position to be reimbursed to the State. During Client C’s time as an SSM I with the State, she had earned $123,184 as of June 2024.

Taking into account the violations of state law discussed above and the manager’s influence that led to improper appointments, we concluded that the manager’s actions constituted gross misconduct. Further, the manager’s actions may have resulted in many other improper appointments. During the course of our investigation, we found evidence—stored on the manager’s state computer and in a small sample of emails he sent his clients—that he has had at least 45 other clients since 2021. As a result, we believe that the manager’s misconduct, which may have been ongoing for the past 20 years, may have resulted in many more unlawful state appointments.

The Manager Used His Own Methods to Unlawfully Obtain State Positions for Himself

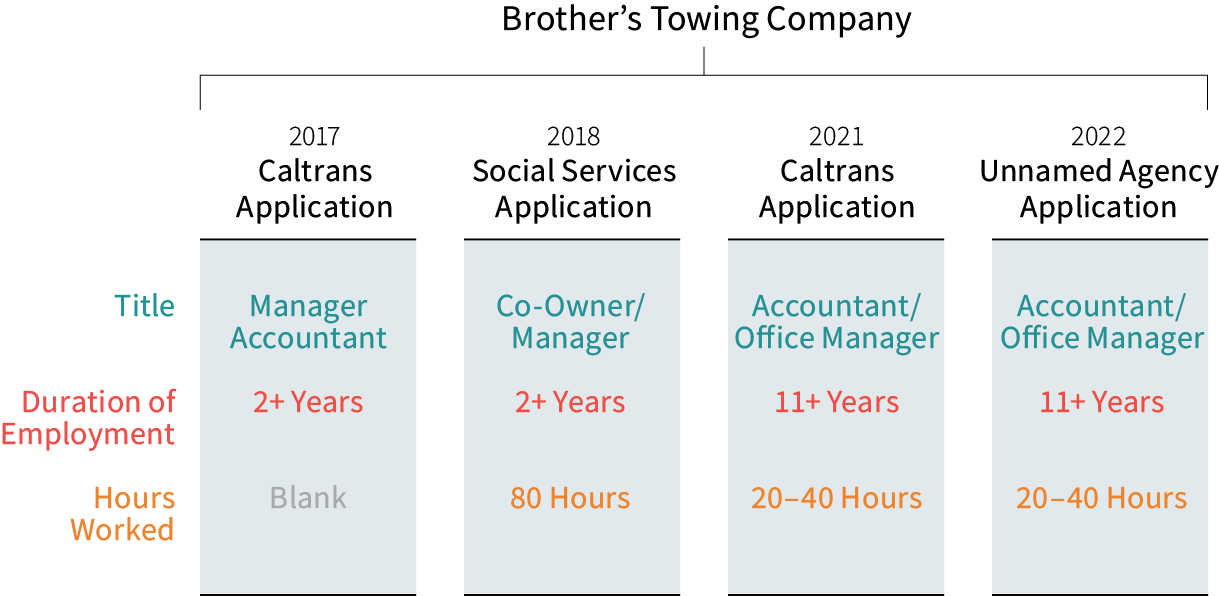

In addition to his misconduct in helping his clients misrepresent their experience and qualifications to obtain state employment, the manager misrepresented his own experience and qualifications on several state job applications. Six different state agencies have employed the manager since 2000, but because of current document retention policies, our investigation focused on the manager’s four most recent appointments, starting in 2017. Our investigation found that he was dishonest on at least four applications that led to a state appointment. Across the four applications the manager submitted from 2016 through 2022, the manager listed work experience for seven different jobs he held in the past, and as shown in Figure 8, our investigation concluded that he submitted false information for six of those jobs.

Figure 8

Elements of Work Experience the Manager Misrepresented on State Employment Applications

Figure 8 shows the elements of the manager’s work experience at six jobs that he misrepresented on six state employment applications. For Job 1 (Towing Co.), the manager misrepresented his title, duration of employment, and hours worked. For Job 2 (Health Care Services), the manager misrepresented the name of his supervisor, his title, duration of employment, hours worked, duties, and reason for leaving. For Job 3 (Caltrans 2017), no misrepresentations were identified. For Job 4 (Landscaping Co.), he misrepresented his duration of employment and duties. For Job 5 (Social Services), he misrepresented the name of his supervisor, his title, hours worked, duties, and reason for leaving. For Job 6 (Cleaning Co.), he misrepresented his duration of employment, hours worked, and duties. For Job 7 (Caltrans 2021), he misrepresented the name of his supervisor and his duties. The source of this information was the investigator’s analysis of the manager’s state employment applications, interview statements, and other related evidence.

Source: Investigator analysis of the manager’s state employment applications, interview statements, and other related evidence.

The Manager Misrepresented His Experience Working for His Brother’s Towing Company

On all four applications, the manager claimed to have worked for his brother’s towing company, about four hours away from his home. However, the manager claimed conflicting information regarding the titles he held, the dates and duration of his employment at the towing company, and the number of hours regularly worked. For example, when we interviewed the manager about the duration of his employment at his brother’s towing company, he stated that he worked at the company when he was not working for the State. According to the manager’s employment records, there was a 28-month gap in his state employment, starting in 2010, and a gap of another five months in 2020. However, on two of his applications, he claimed to have worked at the towing company for more than 11 years, from 2010 to 2021. When we pointed out this discrepancy, he stated that he also worked for his brother’s company while employed with the State.

The manager claimed on different applications to have worked different numbers of hours per week at his brother’s business. The manager claimed to work for the towing company 80 hours per week in his application submitted to the Department of Social Services (Social Services) but changed that claim in his two subsequent applications to 20 to 40 hours per week. He explained this by stating that he worked 80 hours per week starting in 2010 to help his brother start up his business. In addition, when we reviewed the manager’s wage earnings going back to 2019, we found no record of any wages earned from the towing company. When we asked the manager regarding this discrepancy, he claimed that he worked for free. Our investigation concluded that his claim that he worked 80 hours per week at a company located four hours away from his home for zero payment for two years while he was unemployed with the State was not credible. We also did not find credible that the manager would have worked for 20 to 40 hours per week for zero pay at his brother’s company with an eight-hour round-trip daily commute while working full-time for the State as well as at two other jobs mixed in over 11 years.

On his Social Services application, the manager also claimed to be a co-owner of his brother’s business. When presented with evidence from the company’s filings with the Secretary of State that listed different individuals as owners, he admitted that he was never a co-owner and that he identified himself as a co-owner because he helped his brother start up his business. Figure 9 provides a summary of the manager’s claims related to his brother’s business on each application.

Figure 9

Discrepancies in the Work Experience the Manager Claimed to Have at His Brother’s Towing Company

Figure 9 shows the discrepancies on four different state employment applications regarding the work experience the manager claimed to have at his brother’s towing company. In the manager’s application to Caltrans in 2017, he claimed to have worked as a manager accountant for more than two years without indicating his weekly hours. In the manager’s application to Social Services in 2018, he claimed to have worked as a co-owner/manager for more than two years and worked 80 hours a week. In the manager’s applications to Caltrans in 2021 and to an unnamed agency in 2022, he claimed to have worked as an accountant/office manager for more than 11 years and worked 20-40 hours a week, respectively. The source of this information was the manager’s state employment applications.

Source: The manager’s state employment applications.

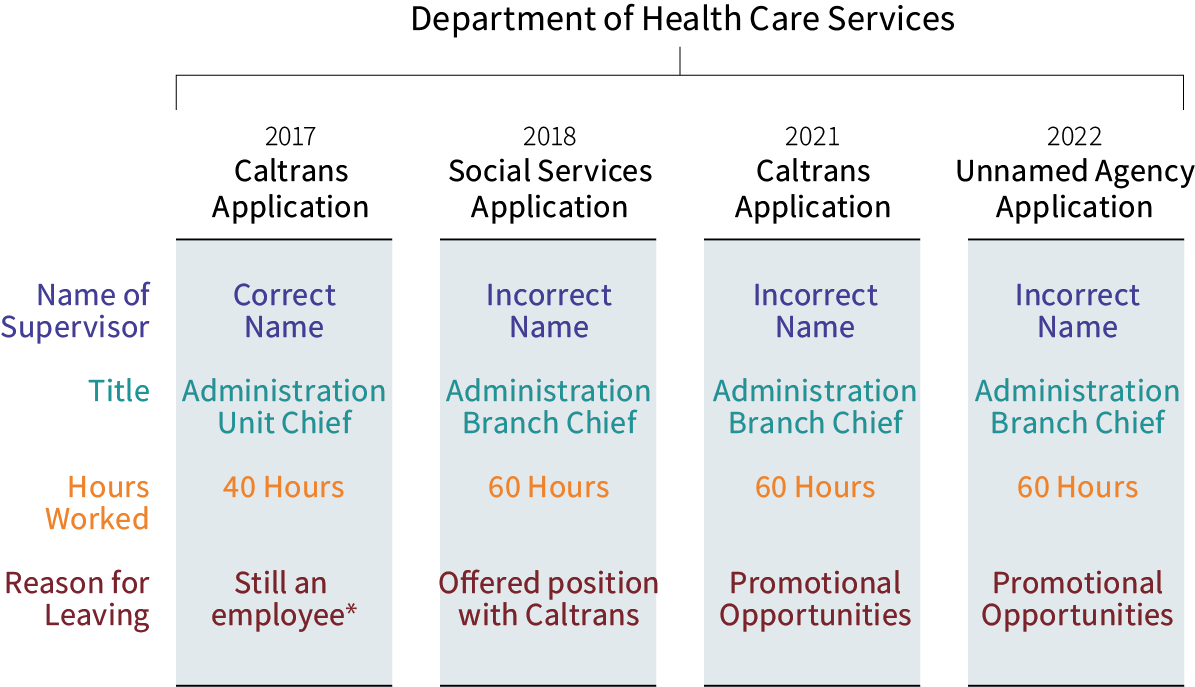

The Manager Misrepresented His Experience Working for Health Care Services

On all four applications, the manager claimed that he worked at Health Care Services. However, our investigation concluded that he misrepresented his time at Health Care Services in multiple ways. For example, on his 2017 application to the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the manager claimed that he was still employed with Health Care Services at the time he submitted his application. However, his employment records prove that he was rejected from probation and was no longer employed by Health Care Services when he submitted the application. He also failed to note the true “Reason for Leaving” on his three subsequent applications. When we spoke to Health Care Services, a representative explained that although the manager was officially rejected from probation, the action was a result of the manager not showing up for work for an extended period and that Health Care Services was unable to get into contact with him. The representative stated that when Health Care Services staff looked online, they found that the manager was actually in jail, and because this occurred during the manager’s probationary period, Health Care Services rejected him from probation.

When we asked the manager about his failure to disclose on his application his true reason for leaving Health Care Services, he could not explain it but stated that he did not intentionally exclude the information to improve his chances of being hired. He also claimed to have informed his supervisors at Caltrans regarding his rejection from probation before his hire. However, Caltrans management told us they did not learn about any performance issues at any other state agencies until after the manager was hired.

In his three subsequent applications to Social Services, Caltrans, and an unnamed agency, the manager also embellished his characterization of his position at Health Care Services, most notably claiming to be a branch chief instead of unit chief. According to the organizational chart in effect at that time, the branch chief oversaw about 56 staff. There were five staff in the manager’s unit.

Health Care Services also refuted the duties the manager claimed to perform. For example, the manager claimed a number of IT procurement-related duties, such as “provided guidance to executives on IT procurement,” “drafted and implemented policies and procedures regarding IT contracts,” “provided direct IT procurement and contract support to various units and division,” and “prepared issue papers … to executive staff by performing technical analysis of proposed technology requests.” Yet a Health Care Services representative stated that his unit did not handle IT procurement. In addition, the representative asserted that, given the manager’s level as a unit chief, he would not provide guidance directly to executives. A summary showing the discrepancies in the manager’s claims on each application is displayed in Figure 10.

Figure 10

Discrepancies in the Manager’s Claimed Work Experience at Health Care Services

Figure 10 shows the discrepancies on four different state employment applications regarding the manager’s claimed work experience at Health Care Services. In the manager’s Caltrans application in 2017, he provided the correct name of his supervisor, claimed that his title was administration unit chief, claimed that he worked 40 hours a week, and indicated that he was still an employee for the reason for leaving. According to the manager’s state employment records, the manager was rejected from probation, effective about two weeks before the date he submitted his application to Caltrans. In the manager’s Social Services application in 2018, he provided the incorrect name of his supervisor, claimed that his title was administration branch chief, claimed that he worked 60 hours a week, and included “offered a position with Caltrans” for his reason for leaving. In his applications to Caltrans in 2021 and an unnamed agency in 2022, the manager provided the incorrect names of his supervisors, claimed that his title was administration branch chief, claimed that he worked 60 hours a week; and included “promotional opportunities” for his reason for leaving. The source of this information was the manager’s state employment applications.

Source: The manager’s state employment applications.

* According to the manager’s state employment records, the manager was rejected from probation, effective about two weeks before the date he submitted his application to Caltrans.

The Manager’s Explanations for the Many Discrepancies in His Descriptions Were Not Credible

When we interviewed the manager, he admitted that some of the information on his applications was false, but he claimed that these were simply mistakes rather than intentional misrepresentations. However, given the breadth and depth of his misrepresentations, combined with witness statements corroborating that he told clients that he lied about his qualifications and encouraged his clients to do the same, we find that the evidence does not support the manager’s explanations. On the contrary, the evidence suggests that the manager likely intentionally misrepresented his qualifications and experience to increase his chances of being hired.

We concluded that all four of the manager’s appointments were obtained with false information and that the manager acted in bad faith. If that is the case, California Code of Regulations, title 2, sections 243.2 and 243.3, provide that all four appointments may be voided and all or a portion of the compensation the manager received while in these appointments, totaling more than $600,000, should be returned to the State. Recently, the manager was terminated from the unnamed agency because the agency determined it needed a different skill set for his position, and the manager returned to his previous SSM II position at Caltrans.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, Caltrans should pursue appropriate corrective or disciplinary action against the manager.

In addition, the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR), in consultation with the State Personnel Board (SPB), should work with the affected agencies to address the unlawful appointments discussed in this report and pursue voiding appointments and collecting compensation reimbursement as appropriate.

Agency Response

CalHR reported to us in September 2024 that it will collaborate with SPB as it proceeds in evaluating the improper activities identified in this report. CalHR will take the lead in coordinating with the impacted departments and will provide direction to each department to help them investigate each individual’s unlawful appointment(s) that occurred under their respective appointing authorities. CalHR noted that it is was finalizing its unlawful appointment policy and accompanying documents for state departments and asserted that the policy must be finalized before providing direction to the impacted departments included in this report.

In general, the other involved state agencies reported that they would wait for additional direction from CalHR. Caltrans reported to us in September 2024 that it plans to take appropriate disciplinary action in response to the report. Also, CAL FIRE stated that Client C had resigned from state service.

Department of General Services

Managers and a Supervisor Engaged in Improper Hiring, and a Manager Improperly Disclosed Confidential Information

CASE I2022-0803

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to allegations that managers and a supervisor within the Department of General Services (DGS) had improperly hired their family members and acquaintances, we initiated an investigation.

About the Agency

DGS’s Facilities Management Division provides building administrative, maintenance, and custodial services to almost 270 buildings statewide. DGS employs approximately 869 custodians, 59 maintenance mechanics, 90 custodian supervisors, and 24 building managers to service and maintain state buildings.

Our investigation determined that from 2020 through 2022, a custodian supervisor and two building managers engaged in improper hiring practices, including hiring family members and providing special assistance to their acquaintances during the hiring process. For instance, a custodian supervisor inappropriately provided the actual interview questions and answers to his cousin so that he could study before his interview, and a building manager improperly interviewed and hired his brother-in-law. One of the building managers also improperly emailed his wife confidential medical information about one of his subordinates.

Background

The majority of this investigation dealt with employees in DGS’s Facilities Management Division who did not follow state laws and DGS policies governing the hiring of state employees. The overarching law governing state employment is found in the California Constitution, article VII, section 1, which requires civil service appointments to be made under a general system based on merit ascertained by competitive examination. Similarly, the California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 250, requires the hiring process for eligible candidates to be competitive and involve an assessment of the qualifications of the candidates.

Civil service appointments must also be made and accepted in good faith to be valid in accordance with California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 243. One required aspect of a good-faith appointment is that the appointing power, including any and all officers and employees of the appointing power who are delegated any responsibility related to the appointment, do all of the following:

- Intend to follow the spirit and intent of any applicable laws, regulations, and policies.

- Make a reasonable and serious attempt to determine how any applicable laws, regulations, and policies should be applied to the appointment.

- Act in a manner that does not violate the rights and privileges of those affected by the appointment, including other eligible candidates.

Eligible candidates must also act in good faith. Section 243 specifies that an appointment is presumed to be accepted in good faith when the candidate answers all questions truthfully and honestly, including but not limited to questions related to experience, education, and level of competency, and the candidate makes sincere and reasonable efforts to provide complete, accurate, and factual information, whether verbally or in documents or other materials.

Nepotism is expressly prohibited in the state workplace. California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 87, requires that appointing powers hire, transfer, and promote all employees on the basis of merit and fitness in accordance with civil service statutes, rules and regulations. The DGS nepotism policy specifies that employees will not use their authority or the influence of their position to secure the authorization of employment or benefit for a person closely related by blood, marriage, or other significant relationship. The policy further explains that any persons closely related by blood, marriage, or other significant relationship may not directly supervise each other, be a part of any hiring, promotional or other beneficial or adverse decision regarding each other, or work on any personnel transactions involving each other, among other prohibitions.