I2025-1 Investigations of Improper Activities by State Agencies and Employees

Waste, Improper Payments, Misuse of State Resources, and Other Improper Governmental Activities

Published: December 12, 2025Report Number: I2025-1

December 12, 2025

Investigative Report I2025-1

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

The California State Auditor, as authorized by the California Whistleblower Protection Act, presents this report summarizing some of the investigations of alleged improper governmental activities that my office has recently completed. This report details five substantiated allegations involving several state agencies. Our investigations found waste, improper payments, misuse of state resources, and other improper governmental activities. Our findings include more than $5 million that state agencies have either wasted, misused, or failed to report.

For instance, an agency wasted more than $4.6 million on monthly service fees for thousands of mobile devices that went unused month after month and, in many cases, for more than two years. Agency management stated that it was unaware that the agency was paying for so many unused devices, but it had access to nonusage reports and invoices that should have identified the problem much sooner. Another case involves an agency that continued to pay an employee who was on extended leave and preparing for retirement for an additional 15 months beyond when his leave hours were fully depleted. The agency did not accurately track the leave hours the employee used and overpaid him more than $170,000. In another example, an agency did not report approximately $400,000 in taxable fringe housing benefits received by employees who rented state-owned housing at below market value. As a result, the affected employees may have significant unpaid tax liabilities.

State agencies must report to my office any corrective or disciplinary action taken in response to recommendations we have made. Their first reports are due within 60 days after we notify the agency or authority of the improper activity, and they continue to report monthly thereafter until they have completed corrective action.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ABC | Alcoholic Beverage Control |

| CalHR | California Department of Human Resources |

| CARB | California Air Resources Board |

| DGS | Department of General Services |

| EDD | Employment Development Department |

| HR | Human Resources |

| SAM | State Administrative Manual |

| SCM | State Contracting Manual |

| SCO | State Controller’s Office |

| UI | Unemployment Insurance |

Summary

Results in Brief

Under the authority of the California Whistleblower Protection Act, the California State Auditor’s Office (State Auditor) conducted investigative work from January 1, 2024, through October 31, 2025, on 2,636 allegations of improper governmental activity. Some of these investigations substantiated improper activities, including waste and inefficiency, improper hiring, and other improprieties. We provide information in this report on only a selection of the cases we have recently investigated as a deterrent for state agencies and state employees so they might avoid engaging in similar improper governmental activities.

Employment Development Department

The Employment Development Department wasted more than $4.6 million in state funds when it paid for monthly service fees on more than 6,200 mobile devices that were not used for four or more consecutive months from November 2020 through April 2025. In some cases, it paid the service fees for mobile devices that remained unused for more than four years.

California Air Resources Board

The California Air Resources Board did not accurately track an employee’s leave hours, continuing to pay the employee for many months after he had fully depleted his leave hours and was no longer working. It consequently overpaid the employee by $171,446 for nearly 15 months from June 2023 through August 2024.

California Department of Veterans Affairs, Yountville Veterans Home

The Yountville Veterans Home operated by the California Department of Veterans Affairs did not report more than $400,000 in taxable housing benefits for employees who rented state-owned housing on the facility grounds from 2023 through 2025. The affected employee-tenants may face significant unpaid tax liabilities.

Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control

A manager at the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control misused state vehicles by using them to commute and for other personal business, such as taking a child to and from school. This manager also stored the vehicles at home without the required storage permit and did not accurately document trips in travel logs as required. We found that the supervisor condoned this manager’s and other managers’ commuting in state vehicles even when no work-related purpose existed for taking vehicles home.

Department of Parks and Recreation

Two employees at the Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) submitted altered receipts to support purchases they made with a state purchasing card. They also failed to record some purchases into State Parks’ inventory and did not follow the proper separation of duties during the purchasing process as state policy requires. One of the employees also allowed other employees to use his state purchasing card.

Introduction

Under the California Whistleblower Protection Act (Whistleblower Act), anyone who in good faith reports an improper governmental activity is a whistleblower and is protected from retaliation.1 An improper governmental activity is any action by a state agency or by a state employee performing official duties that does any of the following:

- Violates state or federal law.

- Is economically wasteful.

- Involves gross misconduct, incompetence, or inefficiency.

- Does not comply with the State Administrative Manual, the State Contracting Manual, an executive order of the Governor, or a California Rule of Court.

Whistleblowers are critical to ensuring government accountability and public safety. The State Auditor protects the identities of whistleblowers and witnesses to the maximum extent required by law. Retaliation against state employees who file reports is unlawful and may result in monetary penalties and imprisonment.

Ways That Whistleblowers Can Report Improper Governmental Activities

Individuals can report suspected improper governmental activities through the toll‑free Whistleblower Hotline (hotline) at (800) 952-5665, by U.S. mail, or through our website at http://www.auditor.ca.gov/whistleblower/.

Investigation of Whistleblower Allegations

The Whistleblower Act authorizes our office to investigate and, when appropriate, report on substantiated improper governmental activity by state agencies and state employees. We may conduct investigations independently, or we may request assistance from other state agencies to perform confidential investigations under our supervision.

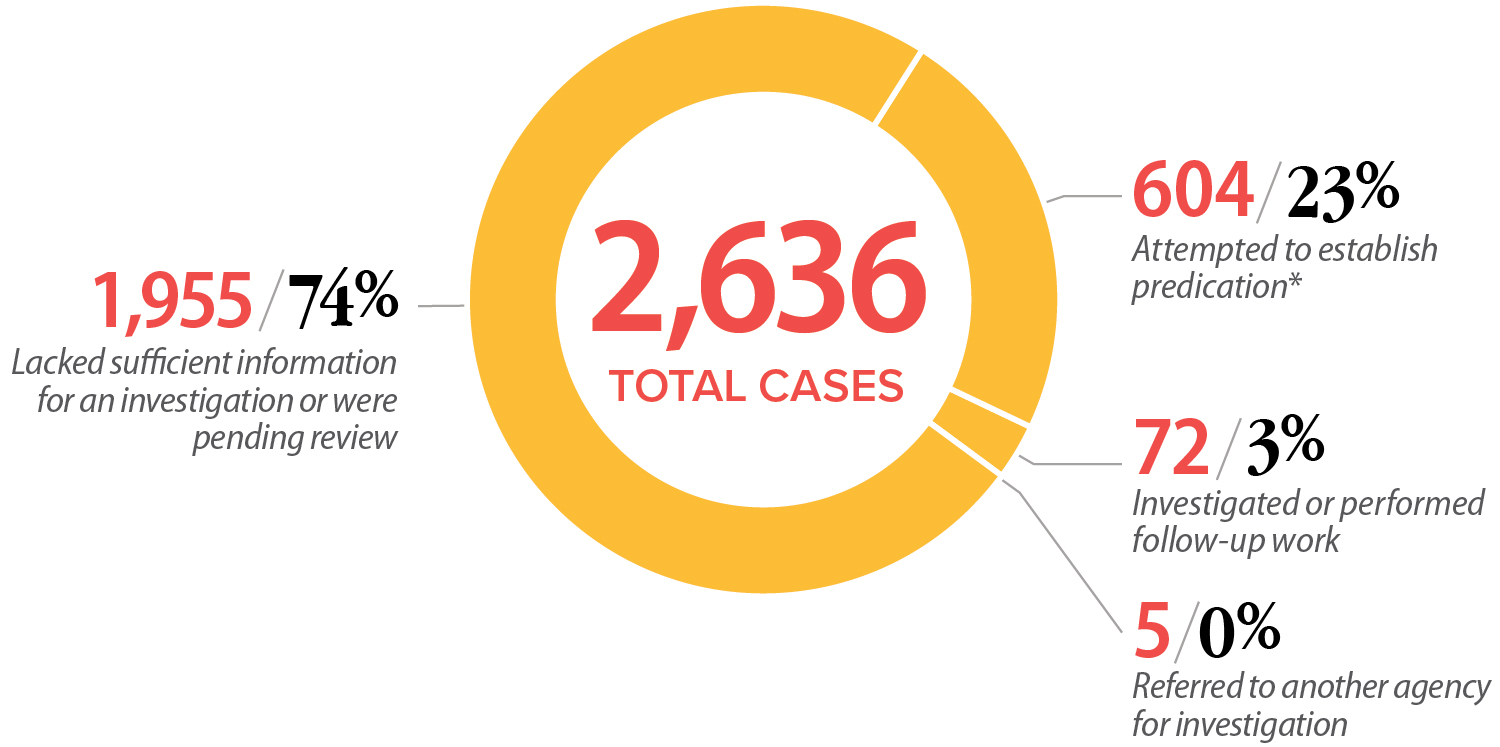

From January 2024 through October 2025, we conducted investigative work on 2,636 cases, some of which we received prior to January 2024. As Figure 1 shows, 1,955 of the 2,636 cases lacked sufficient information for investigation or were pending preliminary review. For another 604 cases, we conducted work or will conduct additional work—such as analyzing available evidence, contacting witnesses, and requesting information from state agencies—to assess the allegations. We independently investigated or performed follow-up work on implementing recommendations for another 72 cases, and we referred five cases to other relevant agencies so they could investigate the matters.

Figure 1

Status of 2,636 Cases, January 2024 Through October 2025

Source: State Auditor.

* Predication is reasonable cause to investigate an allegation. Establishing predication generally includes analyzing available evidence, contacting witnesses, and requesting information from state agencies.

Figure 1 shows a pie chart of the disposition of the 2,636 cases that the investigations division staff worked on from January 2024 through October 2025. 1,955 of the 2,636 cases, or 74 percent, lacked sufficient information for an investigation or were pending review. Staff attempted to establish predication on 604 of the 2,636 cases, or 23 percent. Staff investigated or performed follow-up work on 72 out of the 2,636 cases, or three percent. Five of the 2,636 cases, or zero percent, were referred to another agency for investigation. The source of this information is the California State Auditor.

The Whistleblower Act authorizes the State Auditor to issue public reports when investigations substantiate improper governmental activities. When issuing public reports, our office must keep confidential the identities of the whistleblowers, any employees involved, and any individuals providing information in confidence to further the investigations.

We may also issue nonpublic reports to the heads of the agencies involved and, if appropriate, to the Office of the Attorney General, the Legislature, relevant policy committees, and any other authority we deem proper. Our office cannot release the identities of the whistleblowers or any individuals providing information in confidence to further the investigations without those individuals’ express permission except to law enforcement conducting a criminal investigation.

Our office performs no enforcement functions: this responsibility lies with the appropriate state agencies, which are required to regularly notify us of any actions they take in response to the investigations, including disciplinary actions, until they complete their final actions.

Investigative Results

Employment Development Department

California Air Resources Board

California Department of Veterans Affairs, Yountville Veterans Home

Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control

Department of Parks and Recreation

Employment Development Department

It Wasted More Than $4.6 Million on Mobile Devices That Went Unused

CASE I2025-1099

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that the Employment Development Department (EDD) engaged in a waste of state funds by paying for mobile devices that went unused for months to years, we initiated an investigation and determined that EDD wasted more than $4.6 million for monthly service fees on more than 6,200 mobile devices that were assigned to its Unemployment Insurance (UI) Branch. These mobile devices went unused for four or more consecutive months of our 54-month review period from November 2020 through April 2025. In some cases, the department paid for mobile service on devices that remained in storage for two years or more, resulting in a waste of public funds.

About the Agency

EDD comprises ten branches, one of which is the UI Branch, which administers the unemployment insurance program that provides financial benefits to Californians whose unemployment is through no fault of their own. EDD operates several call centers across the State into which individuals can call and receive assistance with their individual claims.

Background

As of July 2025, EDD’s UI Branch had 2,823 employees, most of whom work in field office call centers, and many of whom serve as employment program representatives (call representatives) who speak with individuals who are filing UI claims. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UI Branch had increased its call representative staffing level from 1,264 in March 2020 to 5,139 in September 2020 to assist with the surge of unemployment claims.

To conduct its many functions remotely during the pandemic and in the years since, EDD deployed mobile devices to many of its employees, including employees in the UI Branch. EDD has multiple accounts with Verizon and T-Mobile, and most of EDD’s Branches have their own account or accounts. Verizon provides EDD a monthly nonusage report that identifies devices that the department has not used for three consecutive months.

At the beginning of our investigation, we reviewed the nonusage report from March 2025, which Table 1 summarizes, and identified one account that contained the majority of the unused devices. The account ending in -70 belongs to the UI Branch, and we focused our investigation on that account.

State law specifies that economic waste by a state agency constitutes an improper governmental activity. The applicable law does not provide a specific definition of economic waste; however, the United States Government Accountability Office’s guidance on the waste of public funds is instructive, defining it to include expending government resources carelessly or incurring unnecessary costs due to inefficient or ineffective practices, systems, or controls.

EDD Engaged in Waste by Paying Monthly Service Fees for 6,285 Mobile Devices That Went Unused for at Least Four Consecutive Months

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, EDD did not widely use or issue mobile devices to its staff. The department also had not previously employed alternative communication platforms such as Microsoft Teams or softphones that would enable staff to perform their duties from outside EDD offices. However, by December 2020, in response to both the Governor’s pandemic stay-at-home order and the resulting substantial increase in the number of submitted UI claims, EDD had procured a total of 7,224 mobile devices such as cell phones, smartphones, and wireless hotspots to allow UI call center staff to work remotely. Yet, by April 2025, 45 months after the Governor rescinded the stay‑at‑home order, EDD was still paying monthly service fees for 5,097 of those mobile devices.

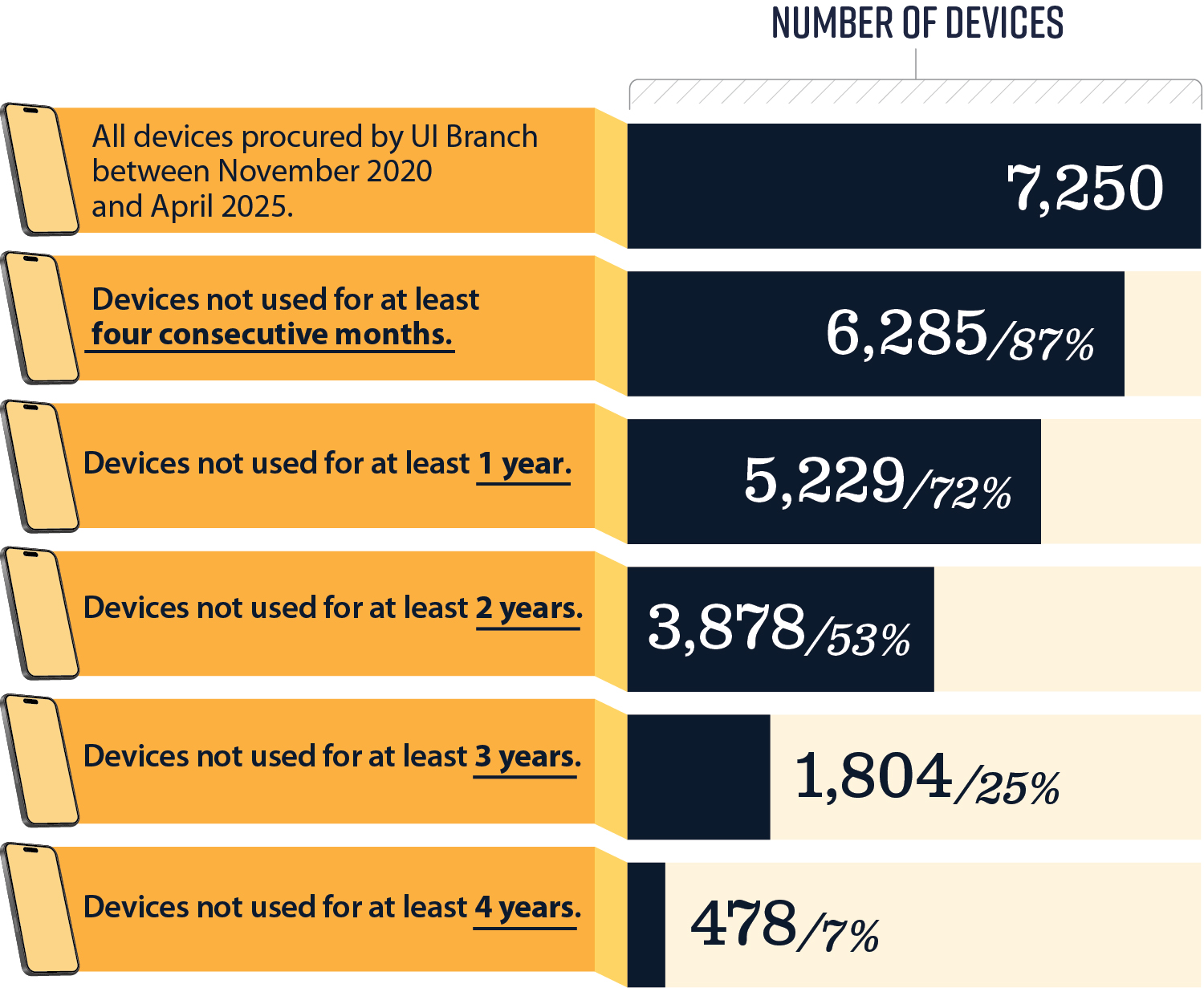

During our investigation, we reviewed the billing data for these mobile devices and observed that many of the devices for which EDD was paying the monthly service fees went unused month after month. We focused on mobile devices that went unused for four or more consecutive months and found that EDD had paid the monthly service fees for 6,285 such devices during the 54 months we reviewed, and the amount of those monthly service fees totaled $4,623,352. As Figure 2 shows, more than half of the devices the UI Branch acquired went unused for at least two years and 25 percent were unused for at least three years. Our analysis also identified 99 devices that were not used at all since EDD began paying the monthly fees in 2020.

Figure 2

Most of the UI Branch Mobile Devices Went Unused for at Least Two Years From November 2020 Through April 2025

Source: Analysis of EDD invoices.

Figure 2 shows the number and percent of UI Branch mobile devices that went unused for a specific amount of time. 7,250 represents the number of all devices procured by the UI Branch between November 2020 and April 2025. 6,285 of the devices, or 87 percent, were not used for at least four consecutive months. 5,229 of the devices, or 72 percent, were not used for at least one year. 3,878 of the devices, or 53 percent, were not used for at least two years. 1,804 of the devices, or 25 percent, were not used for at least three years. 478 of the devices, or seven percent, were not used for at least four years. The source of this information is the analysis of EDD records.

The results of our investigation likely understate the total amount of EDD’s wasteful spending because we only reviewed one of the department’s 22 Verizon accounts. As Table 1 illustrates, EDD had other unused devices, albeit fewer, that it was paying for in other accounts. Further, EDD may have wasted additional funds paying the acquisition costs of the unused devices. However, EDD acquired most of the mobile devices at zero or substantially reduced costs through promotions. For the remaining devices, some of which EDD acquired nearly five years ago, EDD was unable to provide complete and easily accessible purchasing records.

During the investigation, we located a storage room in which the UI Branch kept a stockpile of approximately 420 unassigned mobile devices, many of which had not been used in years. These mobile devices were located in boxes and on shelves, as Figure 3 shows. According to an EDD manager, these were devices that field offices had returned, or they were part of a stockpile that the UI Branch kept to provide to field offices when they hired new employees, or they were available to replace damaged devices. The manager informed us that the number of devices in the storage room is regularly in flux depending on the staffing needs of the field offices. However, we found that the boxes included notes indicating that many of the devices had been there since 2022 or 2023. We selected 14 devices stored in this room and found that none of them had been used in at least 13 months, nine had not been used for 33 consecutive months, and one device had never been used. Nevertheless, EDD was paying the monthly service fees for all of them.

Figure 3

EDD’s Storage Room Contained Devices That Remained Unused for at Least One Year

Source: California State Auditor photos.

Figure 3 displays three pictures of EDD’s storage room showing mobile devices in boxes and on shelves. The first picture appears to show multiple devices inside large brown boxes. The second picture appears to show individual device boxes stacked on shelves. The third picture shows a close up of another large brown box containing dozens of devices. The source of this information is California State Auditor photos.

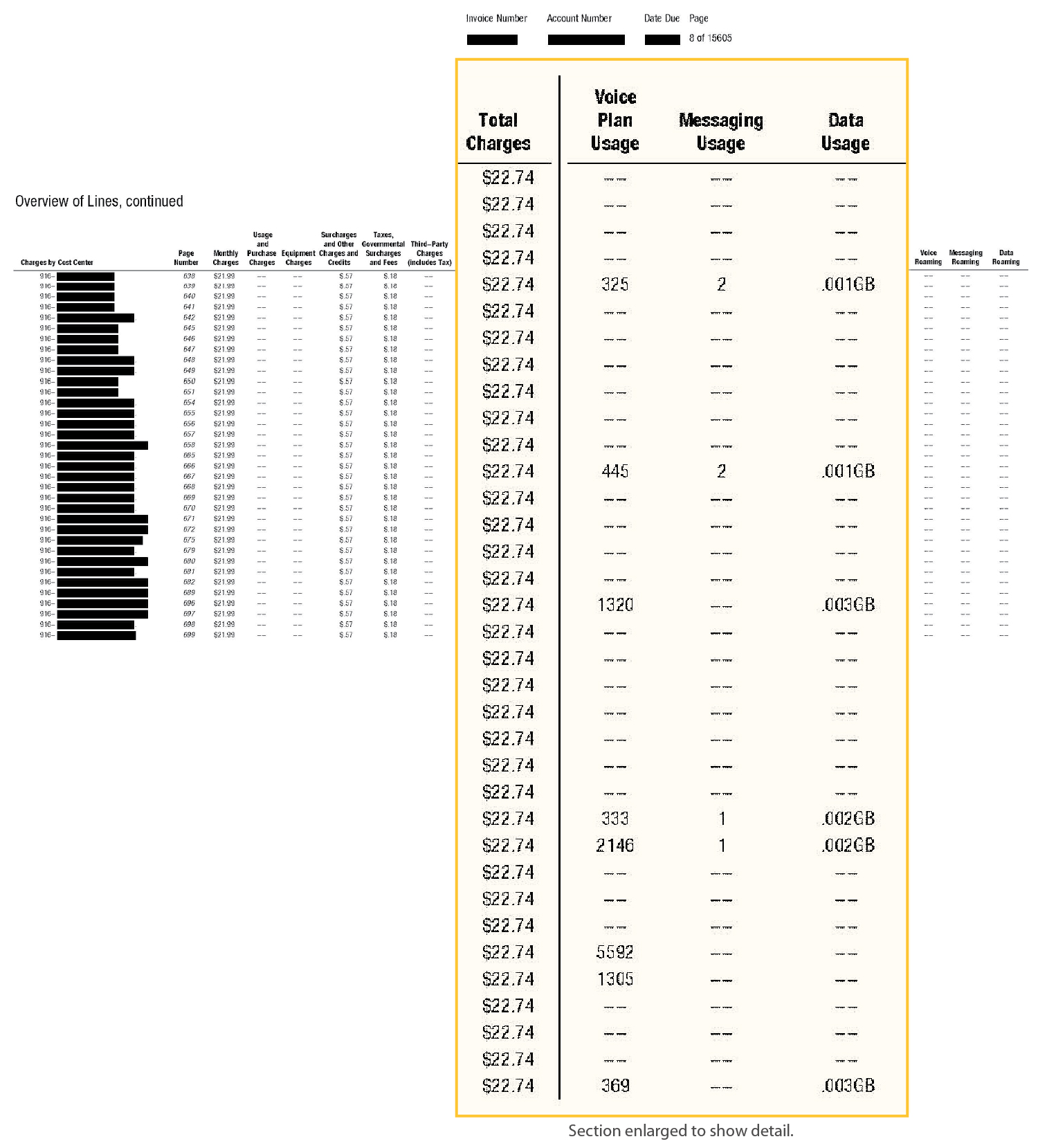

EDD management stated that it had been unaware that it was paying monthly fees for many unused mobile devices; however, we find this explanation implausible for several reasons. First, one EDD official told us that EDD started receiving the nonusage reports from Verizon in 2017. Further, Verizon provided monthly invoices to EDD showing the charges and usage of each mobile phone number line side‑by‑side, as Figure 4 demonstrates. EDD management told us that designated individuals in each branch review the invoices, including the UI Branch, but the UI Branch said that its staff did not evaluate whether the mobile devices were being used. We would have expected EDD management to have reconsidered the need to pay the monthly service fees for so many devices that had no voice, message, or data usage, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4

Excerpt of Invoice That Displays Charges for Many Lines With Zero Usage

Source: Verizon invoice records supplied by EDD.

Figure 4 displays an excerpt of an invoice that shows certain columns enlarged, such as Total Charges, Voice Plan usage, Messaging Usage, and Data Usage. The total charges for each of the devices in the excerpt is $22.74. Most of the lines included on the invoice excerpt show zero usage. The source of this information is Verizon invoice records supplied by EDD.

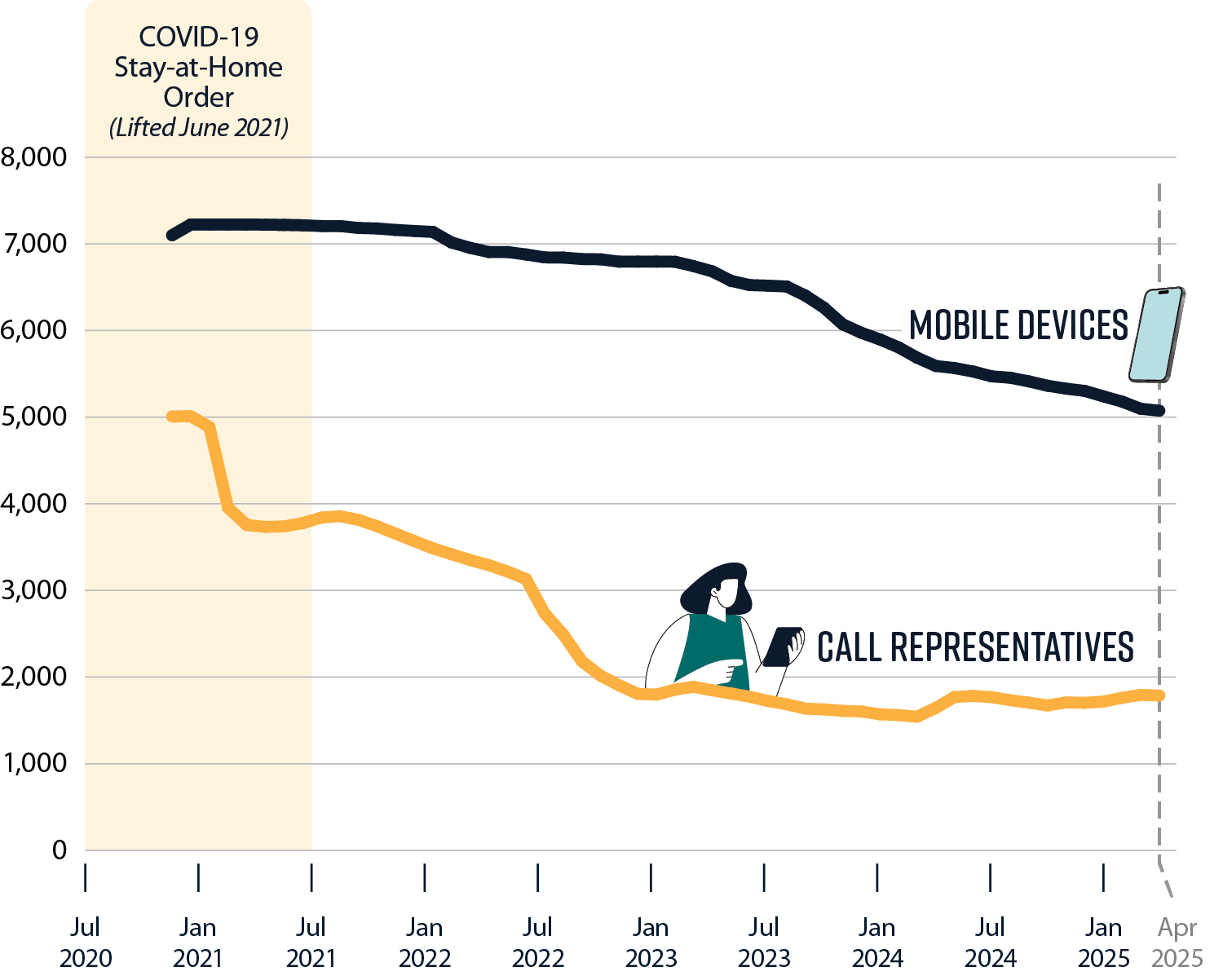

As of April 2025, EDD had 1,787 call representatives in its UI Branch whose duties involved answering calls related to UI claims, but until very recently, it was paying the monthly fees for service to 5,097 mobile devices dedicated to this purpose. Figure 5 shows the disparity between the number of UI call representatives on staff each month from November 2020 through April 2025 and the number of UI mobile devices for which EDD was paying the monthly fees during the same period. Although the number of call representatives significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the number of representatives decreased as the pandemic waned, EDD should have realized that it was paying the monthly fees for significantly more mobile devices than it had employees and taken steps to cancel the unneeded lines.

Figure 5

EDD Consistently Paid Monthly Service Fees for More Mobile Devices Than Call Representatives Assigned to UI Call Centers

Source: Monthly invoices and employee data provided by EDD.

Note: The call representative staffing levels noted in this figure from November 2020 through August 2021 include employees who were redirected from both within EDD and from other state departments to assist with the high levels of unemployment claims EDD was receiving at the time.

Figure 5 shows a line graph displaying the disparity between the number of UI call representatives on staff each month from November 2020 through April 2025 and the number of UI mobile devices for which EDD was paying the monthly fees during the same period. The bottom axis going from left to right starts at July 2020 and ends at April 2025. The left axis going down to up represents the number of devices from zero to 8,000. The number of mobile devices is larger than the number of call representatives throughout the time period displayed. The number of mobile devices is just over 7,000 starting in November 2020 and gradually declines to just more than 5,000 in April 2025. The number of call representatives is at about 5,000 in November 2020, declines to less than 2,000 by January 2023, and then remains somewhat constant through April 2025. The graph notes that the COVID-19 stay-at-home order was lifted in June 2021 and the figure notes that the call representative staffing levels from November 2020 through August 2021 include employees who were redirected from both within EDD and from other state departments to assist with the high levels of unemployment claims EDD was receiving at that time. The source of this information is monthly invoices and employee data provided by EDD.

We recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in unpredictable and unprecedented staffing challenges and that EDD needed to have mobile devices available for unforeseen staffing increases, but even at the height of the pandemic, EDD was paying the monthly fees for about 2,000 more mobile devices than call center staff. By the time the pandemic was over, and staffing levels decreased, it was paying the monthly fees for 3,000 to 5,000 more devices than call center staff. Although obtaining the mobile devices during COVID-19 may have been a good idea to serve the public, continuing to pay the monthly service fees for so many unused devices, especially post-COVID-19, was wasteful.

Since we received this complaint and began investigating, EDD has taken steps to begin addressing this problem. On April 13, 2025, EDD’s Information Technology (IT) Branch worked with the UI Branch to terminate service for 2,825 mobile devices, and 2,761 of those devices belonged to the account we reviewed. EDD also began drafting a policy specifying that it will terminate service for mobile devices that are not used for 90 consecutive days. Management in the IT Branch informed us that it is already implementing this policy, is actively monitoring device usage, and is sending to each branch 30-, 60-, and 90-day nonusage reports.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activity this investigation identified and to prevent such activity from recurring, EDD should take the following actions:

- Immediately review nonusage reports for all accounts EDD has with wireless carriers and work with its respective branches to terminate the service for mobile devices that have gone unused for more than 90 days.

- Within 30 days, finalize its policy to terminate service for mobile devices that are not used for 90 consecutive days and establish and implement a process for enforcing the policy.

Agency Response

EDD reviewed our report and began implementing our recommendations. Beginning in April 2025, EDD established a process whereby its IT Branch actively reviews the nonusage reports provided by the carriers and terminates any active lines that EDD has not used for 90 consecutive days. EDD formally adopted this process in a departmentwide policy that it put into effect on September 3, 2025.

California Air Resources Board

It Did Not Accurately Monitor and Track an Employee’s Leave Balances, Resulting in Overpayment

CASE I2024-13524

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that the California Air Resources Board (CARB) continued to pay an employee on extended leave for many months after he would have exhausted his legitimate leave hours, we initiated an investigation. Our investigation determined that CARB did not accurately track the number of leave hours used by the employee and CARB continued to pay the employee for many months even though his leave hours were fully depleted and he was no longer working. As a result, CARB overpaid the employee for nearly 15 months from June 2023 through August 2024 for a total of $171,446.

About the Agency

CARB’s mission is to promote and protect public health, welfare, and ecological resources through effective reduction of air pollutants while recognizing and considering effects on the economy.

Background

CARB employees keep track of absences and leave usage on monthly timesheets in a timekeeping system called Tempo. Tempo interfaces with the State Controller’s Office’s (SCO) Leave Accounting System (leave system) each month, and CARB relies on the SCO’s leave system as an employee’s official leave record.

Both state law and the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR), as we quote in the text box, make clear that CARB is responsible for ensuring that its employees’ time and attendance records are accurate. A state agency’s failure to comply with these requirements could lead to overpayments and to economic waste and inefficiency, which state law deems to be an improper governmental activity.

Required Monthly Leave Audits

The CalHR Human Resources Manual requires all state agencies to “…create an audit process to review and correct leave input errors on a monthly basis. This includes the review of all leave types accrued or used by all employees on a monthly basis, regardless of whether the leave records are system generated or manually keyed.”

Source: CalHR’s Human Resources Manual.

CARB Did Not Keep Accurate Time Records for the Employee

Our investigation found that the problem regarding the employee’s leave balances likely started after a 2019 CARB reorganization, which resulted in a change to his position number—a unique identifier used for personnel purposes, including payroll and leave accounting. CARB relayed the employee’s updated position number to the SCO. However, the SCO notified CARB that there was an error related to the update. The employee who received the error code and was responsible for resolving it left CARB in 2022, and CARB never addressed the error. From the time of the reorganization in 2019 until the employee’s retirement, the SCO’s leave records did not accurately reflect the leave hours he used.

In 2022, the employee considered retirement but decided instead to take a leave of absence to use up his remaining vacation and other leave balances before officially retiring. CARB’s Leave Usage Pending Retirement policy allowed employees to use up to 90 days of leave before retirement or up to 180 days with approval from one of several senior executives. However, the employee began his leave of absence in July 2022, and that leave continued for about two years—much longer than his legitimately accumulated leave hours should have allowed—while he continued to receive his full salary each month.2 Although the employee’s supervisor approved the indefinite leave of absence, the supervisor’s manager and management in Human Resources (HR) denied knowledge of the leave.

CARB’s lack of oversight of this matter resulted in significant overpayment to the employee. The employee recorded leave on his timesheets each month but claimed to have not noticed any problems with his leave balances and assumed they were accurate. Because CARB never resolved the error with his position number, the SCO leave system did not accurately reflect the absences that the employee included on his timesheets. Further, none of the supervisors and personnel staff who were responsible for reviewing and approving his timesheets each month noticed that his leave balances were not accurate or that he continued to submit timesheets long after his leave hours should have been depleted. As a result, the employee continued to receive his full pay for many months after his leave balances had been exhausted in June 2023. From June 2023 until CARB discovered the problem and canceled his pay warrants in September 2024, CARB continued to pay the employee’s full monthly salary, resulting in an overpayment of $171,446.

CARB finally discovered the problem in 2024 after the employee informed CARB management that he was going to finally retire. The employee notified his management and HR staff of his intent to retire in December 2023; however, he did not complete his retirement application at that time. After exchanging several more emails with the employee and his management between April 2024 and September 2024, CARB HR staff finally became aware that the employee’s leave balances were not accurate and canceled any subsequent pay warrants to avoid additional overpayments. Staff then initiated a leave audit and made its own calculations of the employee’s leave usage. CARB calculated that his leave should have been exhausted in October 2023 and arranged for his retroactive retirement accordingly. CARB also retroactively corrected the employee’s leave balances in the SCO leave system and sent a request to the SCO to void the salary payments it made to him for October 2023 through August 2024. CARB calculated that the employee had received overpayment of $124,705 and needed to repay $86,612—the net salary he received after his retroactive retirement date.

However, we reviewed CARB’s audit and found that it contained at least three errors that resulted in CARB miscalculating the employee’s leave usage and salary overpayment by $46,741: The total amount of his overpayment was actually $171,446.

- The audit’s calculation gave the employee credit for 428 hours of sick leave that he did not include on his timesheets and did not claim that he was sick or caring for a sick family member. Employees may use sick leave for qualified absences only, and CARB did not verify that his absences met the qualifications.

- The audit’s calculation included Professional Training and Development hours to cover some of the employee’s absences even though he did not include these hours on his timesheets.

- The audit’s calculation gave the employee credit for more holiday credit hours than he had earned.

These errors resulted in CARB giving the employee credit for about four more months of pay than it should have.

Control Deficiencies Contributed to the Problem and Ultimately Resulted in Waste and Inefficiency

Our investigation found several controls that were either deficient or that CARB ignored, which contributed to CARB’s inaccurate records and prevented it from detecting the problem sooner. For instance, the employee’s indefinite leave of absence violated CARB’s Leave Usage Pending Retirement policy. Although the employee’s supervisor appears to have ignored the policy, CARB did not have a control in place to identify the policy violation. Also, CARB’s timesheet reviews and approvals were ineffective. Finally, CARB did not perform regular leave audits, and it did not have a process in place to compare leave recorded on the employee’s timesheet with the SCO leave system. These control deficiencies resulted in waste and inefficiency because CARB has spent significant amounts of time and resources to evaluate the employee’s leave balances and then attempt to recover the overpayments it made.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, CARB should take the following actions:

- Reassess its leave audit calculations and pursue repayment of the overpayments it made.

- Confirm that all position number changes are error-free and up-to-date in the SCO’s leave system.

- Correct the control deficiencies we identified, including by creating an audit process to review and correct leave input errors each month as the CalHR Human Resources Manual requires.

- Determine whether its managers and supervisors require additional training on CARB’s leave policies and provide such training as needed.

Agency Response

CARB reported that it reviewed the leave audit it conducted, addressed the errors we cited in our report, and is in the process of collecting from the employee the overpayment it made. CARB confirmed that it has corrected the employee’s position number with the SCO and that no other employees were affected as a result of an error like the one with this employee’s position number. It also stated that it will develop an audit process to ensure that no other position numbers are incorrect with the SCO. Further, CARB is revising its Leave Usage Pending Retirement policy and has implemented a monthly leave activity and balance audit process. Finally, CARB stated that it plans to develop additional training for its managers and supervisors regarding leave policies.

California Department of Veterans Affairs,

Yountville Veterans Home

It Has Not Reported Some Taxable Housing Benefits, Which Could Result in Future Tax Liabilities for Employee-Tenants

CASE I2025-2429

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

We received an allegation that the California Department of Veterans Affairs’ (CalVet) Yountville Veterans Home (Yountville) did not report to the State Controller’s Office (SCO) the taxable fringe benefits for housing that some employees received when Yountville charged them less than fair market value in rent. In response, we initiated an investigation and determined that Yountville did not report more than $400,000 in taxable housing benefits for employees who rented housing (employee-tenants) from 2023 through 2025. As a result of Yountville not reporting this benefit as taxable employee income, the affected employee-tenants may have significant unpaid tax liabilities.

About the Agency

CalVet serves California veterans and their families. Among its services, CalVet offers affordable residential independent living programs, long-term care, and skilled nursing to aged and disabled veterans and their spouses who can reside in one of its eight veterans homes.

Background

Yountville is currently the only one of CalVet’s veterans homes at which employees may optionally rent housing onsite. Yountville’s ability to lease such state-owned housing to its employees not only helps support the operation of the veterans home, but the availability of this housing also serves as a recruitment and retention tool for staff.

State regulation delegates the authority and responsibility to agencies with state‑owned housing to apply and adjust rental rates for their housing. If an agency charges an employee-tenant rent that matches the fair market value of the property, there are no income tax implications. However, when an agency charges an employee rent that is below fair market price—less than what the property would rent for in an open market—the difference between the fair market value and the actual rent charged becomes a reportable and taxable fringe benefit for the employee-tenant. The State Administrative Manual (SAM) notes that a tax liability exists when an employee pays rent that is below fair market value for state-owned property and requires agencies to report taxable fringe housing benefits to the SCO every month. SAM also directs agencies to the CalHR Human Resources Manual for information on reporting and tax withholding requirements. CalVet Human Resources is responsible for reporting to the SCO taxable fringe housing benefits for employee‑tenants at Yountville, but CalVet personnel rely on the benefit amounts that Yountville reports to them.

To determine fair market value for state-owned housing, CalHR’s Human Resources Manual requires agencies to conduct an appraisal once every five years and to conduct a desk review update every year. For Yountville, the Department of General Services (DGS) conducted appraisals for its habitable state-owned housing in 2023.

In Report 2018-112, January 2019, our office noted that CalVet’s poor management of state-owned housing at Yountville resulted in, among other things, CalVet’s failing to inform employee-tenants of the taxable income they received from the fringe benefit of the below-market-rates they paid for rent. Our audit recommended that CalVet annually review the rental rates for its employee housing units to ensure consistency with market value and that it should adjust the rental rates accordingly. In 2020, CalVet provided us with evidence that it had assessed rental rates in 2019, increased some rents to fair market value, and was incrementally increasing the rents for the other employee-tenants.

Its Employee-Tenants Have Earned More Than $400,000 in Taxable Fringe Housing Benefits That Yountville Has Not Reported to the SCO Through CalVet Human Resources

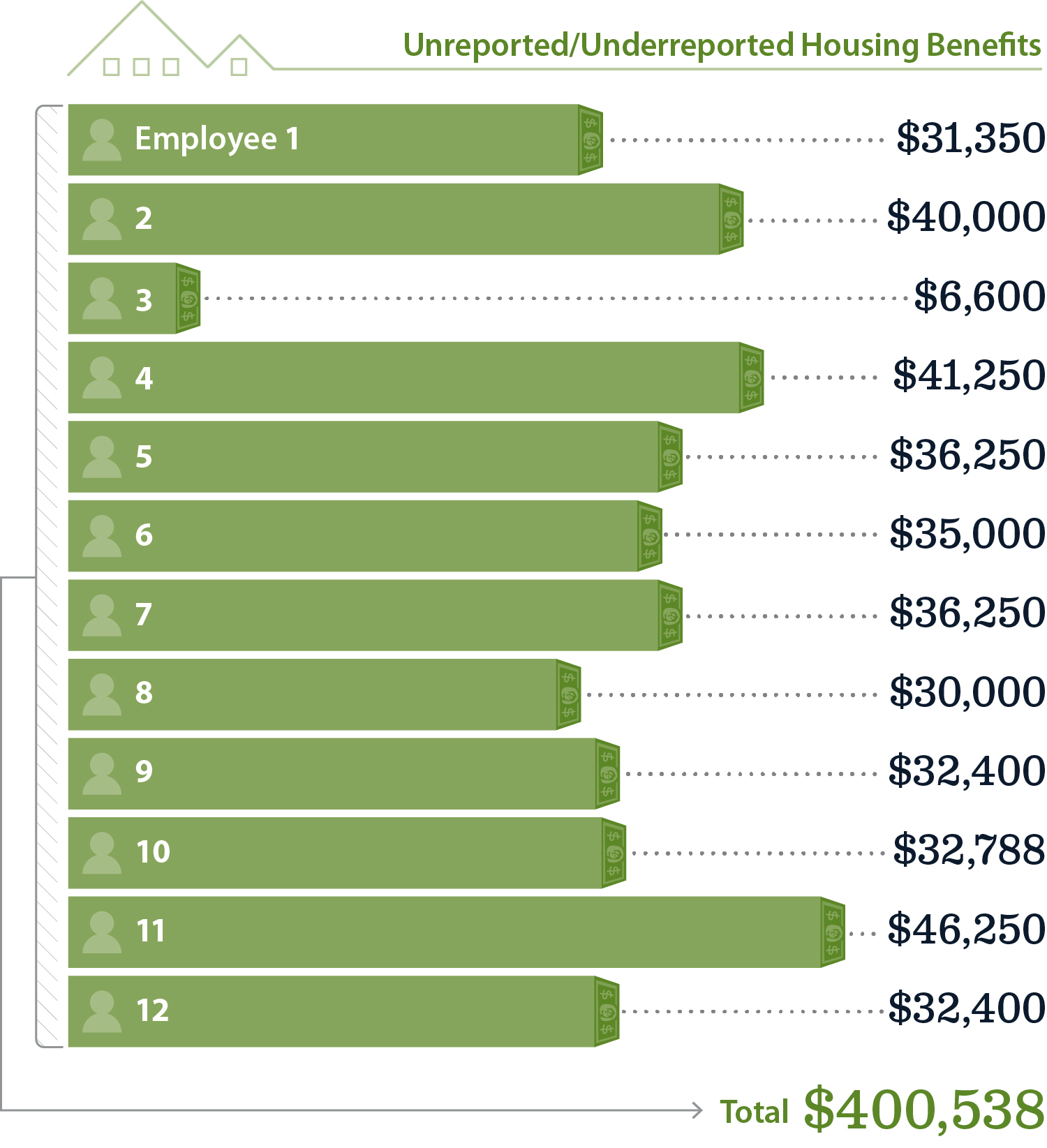

We determined that since 2023, CalVet Human Resources has not reported to the SCO $400,538 in taxable fringe housing benefits because Yountville has not informed CalVet personnel of these housing benefits. From 2023 to 2025, Yountville leased 12 of its state-owned housing units to employee-tenants at less than fair market value. CalVet Human Resources reported some taxable fringe housing benefits to the SCO for only three of those 12 employee-tenants, and the agency did not report any taxable fringe housing benefits to the SCO for the remaining nine employee‑tenants. However, even the taxable fringe housing benefits that they did report were inaccurate. Specifically, Yountville used outdated fair market values from before 2023 for the three employee‑tenants’ rental units when it calculated taxable fringe housing benefits. CalVet Human Resources did not adjust the employees’ taxable fringe housing benefits that it reported to the SCO to reflect DGS’s more recent appraisals because Yountville did not communicate the need to make the adjustments. CalVet Human Resources should have reported $456,675 in taxable fringe housing benefits for the 12 employees who paid rent below fair market value but reported only $56,137. As a result of Yountville’s failure to inform CalVet Human Resources of the need to report the correct taxable fringe housing benefits for its employee-tenants, the affected employee-tenants might not have paid their income tax liabilities and could now face the liabilities that Figure 6 outlines.

Figure 6

CalVet Has Not Reported or Has Underreported the Taxable Fringe Housing Benefits for 12 Yountville Employee-Tenants

Source: CalVet lease agreements and employee payment records.

Figure 6 depicts a bar graph showing the amount of unreported or underreported housing benefits for each of the12 employees. Employee 1 either did not report or underreported $31,350. Employee 2 either did not report or underreported $40,000. Employee 3 either did not report or underreported $6,600. Employee 4 either did not report or underreported $41,250. Employee 5 either did not report or underreported $36,250. Employee 6 either did not report or underreported $35,000. Employee 7 either did not report or underreported $36,250. Employee 8 either did not report or underreported $30,000. Employee 9 either did not report or underreported $32,400. Employee 10 either did not report or underreported $32,788. Employee 11 either did not report or underreported $46,250. Employee 12 either did not report or underreported $32,400. The total amount for the 12 employees is $400,538. The source of this information is CalVet lease agreements and employee payment records.

Despite the fact that Yountville’s policy designates a manager with the responsibility to ensure that the agency reports taxable fringe housing benefits to the SCO in a timely manner and that the manager’s duty statement also specifies the responsibility of reporting housing benefits to CalVet, the manager acknowledged that they have not reported taxable fringe housing benefits since they started in their position. The manager explained that they report state-owned housing rent charges to CalVet Human Resources but that they were not familiar with the responsibility of reporting taxable fringe housing benefit amounts. Therefore, CalVet Human Resources would be unaware of the number of employee-tenants or the amount of taxable fringe housing benefits to report to the SCO every month.

Although DGS appraised all of Yountville’s habitable rental properties in 2023, Yountville has not increased the rent at some of those properties to match DGS’s appraisal of their fair market values. Yountville staff indicated that Yountville has not increased the rent because CalVet did not completely agree with DGS’s appraisals and has asked DGS to adjust its appraisal results. However, staff reported that CalVet has not received a resolution from DGS.

Even though CalVet has the authority to set and adjust rental rates for its state‑owned housing, it has not made any significant progress since DGS’s 2023 appraisals in determining whether to increase rent for employee-tenants who pay rent below fair market value. Regardless of whether it eventually increases rent to better match market rates, CalVet has a current and monthly obligation to report to the SCO the taxable fringe housing benefits for employee-tenants who pay rent that is below fair market value. SAM specifies that an agency’s failure to report taxable fringe benefits in a timely manner violates legal requirements and subjects the agency to civil and criminal actions.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, CalVet should take the following actions:

- Report to the SCO previously unreported and underreported taxable fringe housing benefits for the 12 employee-tenants and inform these employee-tenants of their potential tax liabilities.

- Provide training to the manager and to CalVet’s Human Resources personnel who report taxable fringe housing benefits to ensure that all individuals involved in such reporting to the SCO understand their responsibilities.

- Develop and document a process in which the manager and CalVet Human Resources consult monthly regarding the information they must each determine to make accurate reports to the SCO.

Agency Response

CalVet responded that it concurs with our recommendations. It reported that it will report to the SCO the taxable fringe housing benefit amounts for the 12 employee‑tenants and will notify them of their potential tax liabilities. It also reported that it will establish a procedure that will outline the roles and responsibilities of the Yountville manager and CalVet’s Human Resources personnel on state-owned housing, which will serve as a training guide to ensure consistency and accurate reporting to the SCO. CalVet anticipates accomplishing these steps by the end of 2025. CalVet reported that in the meantime, it is facilitating monthly communications between the Yountville manager and its Human Resources personnel to verify the accuracy of the compliance reporting to the SCO.

Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control

Several Managers Misused State Vehicles, and Their Supervisor Condoned It

CASE I2025-0539

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that a manager at the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) misused state-owned vehicles (state vehicles), we initiated an investigation. Our investigation determined that a manager (Manager A) misused state vehicles to commute and for other personal business, including taking a child to and from school. We also found that Manager A regularly stored state vehicles overnight at home without a Vehicle Home Storage Permit (home storage permit) and did not accurately document travel on vehicle travel logs. Our investigation further revealed that Manager A’s supervisor condoned managers, including Manager A, commuting in state vehicles even when no work-related purpose existed for taking the vehicles home.

About the Agency

ABC regulates the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages in the State. It investigates applications for licenses to sell alcoholic beverages and reports on the moral character and fitness of applicants and the suitability of premises where sales are to be conducted.

Background

ABC staff use state vehicles to visit sites where license applicants intend to do business, and they do the following: ensure that public notices are properly posted; determine the proximity of the applicants’ business sites to consideration points such as schools, churches, and residences; and verify that applicants have the facilities and equipment listed in their applications. Most ABC vehicles that its staff use are equipped with telematics monitoring systems. This technology enables remote monitoring and management of assets, such as vehicles, using GPS, sensors, and wireless networks to track vehicle information, such as speed and location.

California law mandates that state employees use state vehicles for state business only. It is unlawful for state employees to use public resources for personal purposes that are not authorized by law, and the law makes misuse of state property a cause for discipline. Vehicle misuse includes driving a state vehicle to or from an employee’s home, unless the use meets one of the following defined exceptions:

- The employee is departing or returning from an official trip away from the employee’s headquarters in circumstances that make it impracticable for the employee to use other means of transportation or when the employee’s home is reasonably in route to or from headquarters or other locations where the employee is to report on the following workday.

- The vehicle is to be used in the conduct of state business on the same day or before the next succeeding workday and where such later use has been authorized in writing.

- The vehicle is parked at or near the employee’s home because no state garage facility is available.

- The employee is required to respond to urgent or emergency calls outside of regular working hours.

- The employee is required to work unplanned overtime such that no other practical means of getting home is available to the employee.

State employees may not transport people not involved in state business in state vehicles, except with approval by an immediate supervisor, and employees must record in a vehicle travel log the date, time, daily miles traveled, itinerary, and information regarding the vehicle’s overnight storage. Finally, if an employee frequently stores a state vehicle at or near the employee’s home, the law requires the employee to have a home storage permit.3

A Manager Misused State Vehicles to Commute and to Transport a Child to and From School

During the period from September 2024 through February 2025, Manager A used a state vehicle for the 62-mile round-trip commute between Manager A’s home and office on at least 17 occasions. Manager A initially denied ever taking a state vehicle home without having a work-related purpose for doing so; however, our review of telematics data and other evidence revealed that Manager A did not make any ABC‑related stops or satisfy any of the exceptions in state law that would have allowed Manager A to commute in a state vehicle on these 17 occasions. Manager A ultimately acknowledged sometimes taking state vehicles home to save time during the commute even though the office, where the vehicles should have been stored, was in route either to or from the other work locations Manager A was to visit. In these instances, instead of driving the state vehicles an extra 62 miles to and from home, Manager A could have easily left a few minutes earlier to travel to the office to retrieve a state vehicle in the morning or stopped at the office while returning home to drop off the state vehicle.

Manager A also violated state law by transporting people who were not state employees in state vehicles. The telematics records show that Manager A made stops at an elementary school on 30 occasions from September 2024 through February 2025. Manager A acknowledged transporting a child to school in a state vehicle on around 20 or 22 occasions without obtaining a supervisor’s approval and being aware that this was not allowed. Manager A also acknowledged using state vehicles on several occasions to travel to the child’s school to bring items that the child had forgotten.

During the short period in question, we found that Manager A’s misuse of state vehicles totaled at least 1,216 miles at a cost to the State of $820. Further, if Manager A used state vehicles in a similar fashion since being appointed in 2022, we estimate that Manager A’s vehicle misuse may have totaled as much as $4,952. In addition to this, we identified many other questionable trips, but we were unable to determine whether these trips were work related. Although Manager A claimed that these trips were likely related to licensing visits, Manager A did not recognize many of these addresses and was unable to provide documentation that they were related to work. As such, Manager A’s vehicle misuse may have been even greater than what we have calculated.

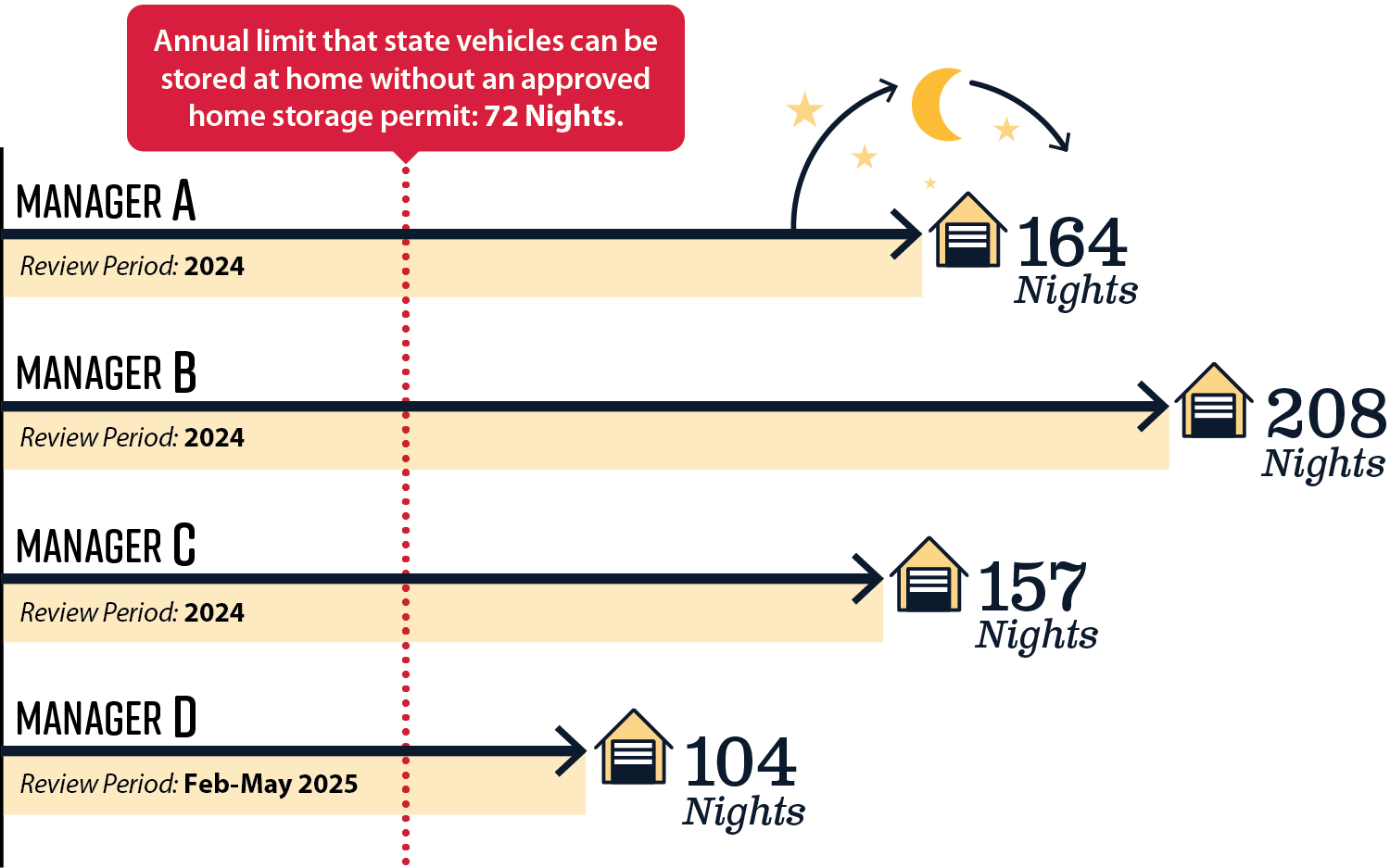

Manager A also violated state law by regularly keeping state vehicles at home overnight without a home storage permit. During our investigation, we found that Manager A stored state vehicles at home on 164 nights in 2024, more than double the number of nights an individual is allowed to store a vehicle at home without a permit. Both Manager A and Manager A’s supervisor confirmed that Manager A has never had such a permit and does not meet the qualifications to have one.

Finally, Manager A did not properly record trips on the vehicle travel log. Specifically, Manager A failed to record trips in the log on 12 instances from September 2024 through February 2025. When Manager A did record trips in the log, Manager A incorrectly indicated that the vehicle was stored overnight in a state facility instead of specifying that the vehicle was stored at home on each of those nights.

The Manager’s Supervisor Condoned the Misuse of State Vehicles by Several Managers Under the Supervisor’s Regular Supervision

When we interviewed Manager A’s supervisor, the supervisor believed that the way in which Manager A used state vehicles was allowable. In fact, the supervisor informed us that the managers are allowed to take state vehicles home overnight, even if they do not have a work-related purpose for doing so, as long as they do not do so with such frequency that they exceed the threshold that would require them to have home storage permits. The supervisor was aware that Manager A and other managers under the supervisor’s regular supervision used state vehicles for their commutes and affirmed that the supervisor had authorized it, thereby also violating state law by permitting the misuse of state resources. Further, the supervisor made other statements, such as “we have allowed that,” that implied that using state vehicles in this manner was a common practice in the supervisor’s division and perhaps in the entire department.

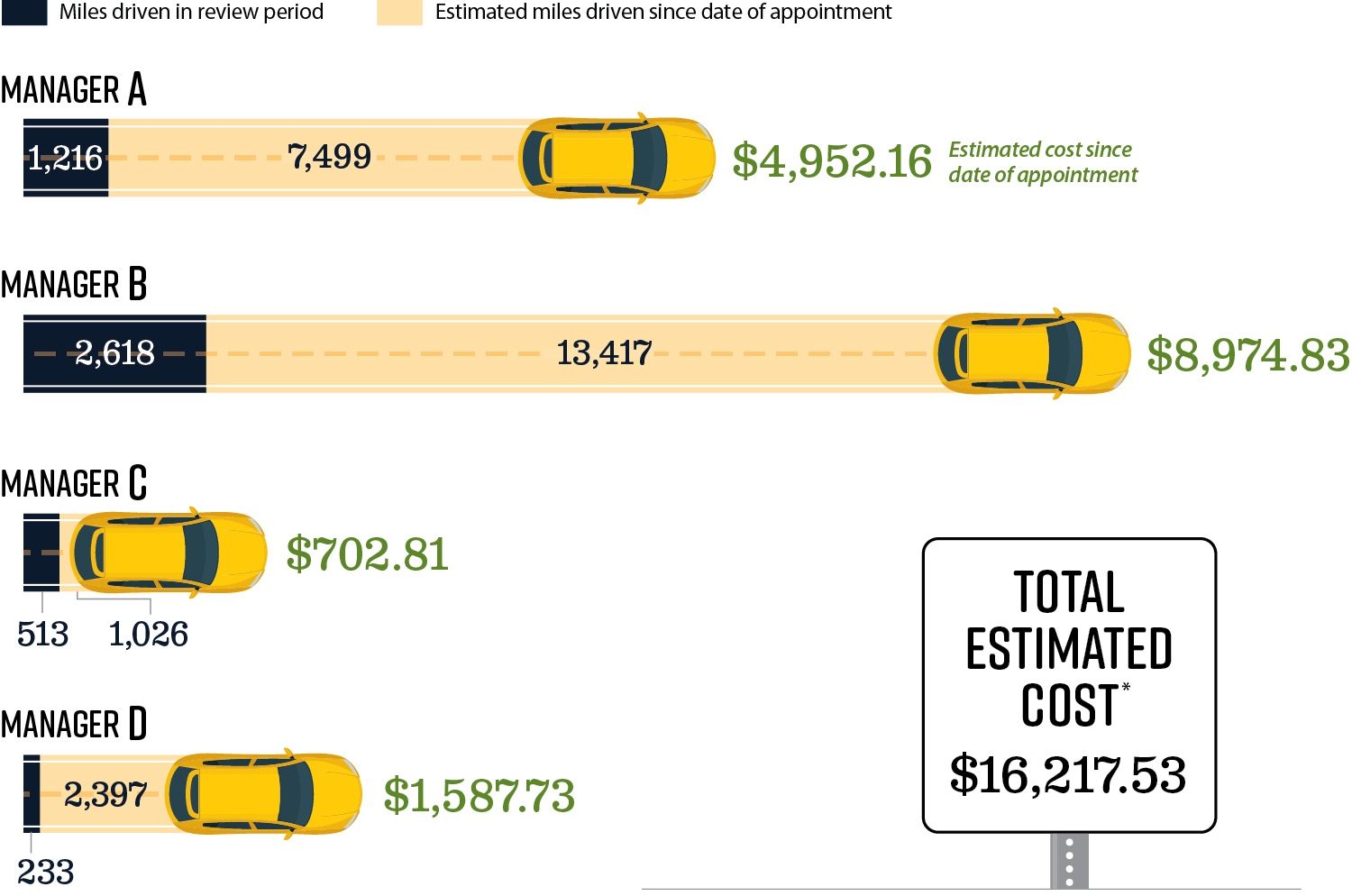

In response to the supervisor’s admission, we reviewed additional evidence, including travel logs and telematics data, and we found three other managers who report to the supervisor—Managers B, C, and D—who also sometimes used state vehicles for commuting to their personal residences. Most significantly, we found that from September 2024 through February 2025, Manager B used a state vehicle to commute—with no associated business purpose—between the ABC office and Manager B’s home on at least 43 occasions, traveling 2,618 miles at a cost to the State of $1,776. Manager B stored state vehicles at home on 208 nights in 2024 without having a home storage permit. The following figures detail our findings on vehicle misuse by all four managers. As Figure 7 notes, we estimate that the cost of these managers’ vehicle misuse may have totaled more than $16,000 if the managers used the state vehicles with similar frequency since their respective appointment dates to their current positions. Figure 8 shows that the managers were storing state vehicles at their homes much more frequently than allowed without an approved home storage permit.

Figure 7

Estimated Cost of Vehicle Misuse

Source: Analysis of ABC vehicle travel logs, telematics records, and employment records.

* We based this estimate on the number of improper commute miles the managers may have driven state vehicles since their appointment dates, and we calculated the results using the monthly average of improper commute miles we identified during the specific period we reviewed and the IRS Standard Mileage Rates in effect during previous months.

Figure 7 shows the miles driven and the estimated cost of vehicle misuse for four managers. Manager A drove 1,216 miles in the review period and an estimated 7,499 since the date of appointment for an estimated cost of $4,952.16. Manager B drove 2,618 miles in the review period and an estimated 13,417 miles since the date of appointment for an estimated cost of $8,974.83. Manager C drove 513 miles in the review period and an estimated 1,026 miles since the date of appointment for a cost of $702.81. Manager D drove 233 miles in the review period and an estimated 2,397 miles since the date of appointment for a cost of $1,587.73. The total estimated cost for the four managers is $16,217.53 The figure notes that we based this estimate on the number of improper commute miles the managers may have driven since their appointment dates and we calculated the results using the monthly average of improper commute miles we identified during the specific period we reviewed and the IRS Standard Mileage Rates in effect during previous months. The source of this information is analysis of ABC vehicle travel logs, telematics records, and employment records.

Finally, the managers’ supervisor acknowledged being unaware that subordinate managers had so frequently stored state vehicles at their homes and that anyone in a supervisory role is responsible for monitoring the proper vehicle use of the employees they supervise. The supervisor acknowledged likely signing ABC’s vehicle policy without having read it.

Figure 8

Frequency That Managers Stored State Vehicles at Home

Source: Analysis of ABC vehicle travel logs, telematics records, and employment records.

Figure 8 shows the frequency with which each of the four managers stored state vehicles at home. Manager A stored the vehicles at home 164 nights during the 2024 review period. Manager B stored them at home 208 nights during the 2024 review period. Manager C stored them at home 157 nights during the 2024 review period. Manager D stored them at home 104 nights during the February to May 2025 review period. The figure notes that the annual limit that state vehicles can be stored at home without an approved home storage permit is 72 nights. The source of this information is analysis of ABC vehicle travel logs, telematics records, and employment records.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities this investigation identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, ABC should take the following actions:

- Review the vehicle use of the employees identified in this report and recoup the cost of any state vehicle misuse.

- Take appropriate corrective action for those individuals.

- Ensure that the supervisor and managers involved in this investigation have received training on and are familiar with ABC policy and state law related to state vehicle use.

- Determine whether the department’s vehicle misuse extends beyond managers who report to the supervisor and address identified misuse, if any.

Agency Response

ABC informed us that it completed its own investigation of the vehicle misuse and had placed one manager on administrative leave. It stated that further corrective action was pending executive review of its investigation. ABC also plans to have its employees refresh their knowledge of its vehicle use policy. It said it would ensure that its employees are trained on that policy and state law related to vehicle use. ABC will require employees to obtain executive-level approval to store a state vehicle at an employee’s home until it can train its employees and implement improved controls. Finally, ABC stated it was analyzing vehicle use data statewide to determine whether vehicle misuse extends beyond the managers identified in our report.

Department of Parks and Recreation

Employees Circumvented Controls Over Purchasing and State Assets

CASE I2025-1229

Summary of Allegations and Investigative Results

In response to an allegation that employees at the Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) made improper purchases, we initiated an investigation. We determined that two employees (Employees A and B) supported their CAL-Card purchases by submitting receipts that they altered or created, not the original purchase receipts that the vendors provided. We found that Employees A and B failed to record their purchases into State Parks’ inventory as required, and these two employees did not follow the separation of duties in the purchase process as state policy requires. Finally, our investigation revealed that Employee A allowed other State Parks employees to use his CAL-Card to make purchases.

About the Agency

State Parks preserves the State’s biological diversity, protects its most valued natural and cultural resources, and creates opportunities for high-quality outdoor recreation. State Parks’ responsibilities include maintaining roads and trails, monitoring wildlife, restoring natural areas, and performing other environmental compliance activities.

Background

State Parks’ staff purchase many of the items they need for their work and often use CAL-Cards to make these purchases. CAL-Card is the State’s credit card program and is a payment method. Agencies that participate in the program must adhere to all procurement laws and regulations, and state agencies must designate responsibilities for CAL-Card cardholders, including the responsibility that cardholders reconcile statement transactions to receipts and supporting documentation. Further, the State Contracting Manual (SCM) mandates that only the assigned cardholder may use the CAL-Card issued to that person.

The State Administrative Manual (SAM) requires state agencies to log all purchases on a property register and to create an internal policy that specifies items to which the agency should affix identification tags. State Parks’ Administrative Manual requires all property valued at more than $400 to be entered into inventory. Finally, SAM requires a separation of duties for authorizing, receiving, recording, and reconciling procurement transactions so that no one staff person is involved in more than one key function for a given transaction.

Employees Submitted Receipts That They Created to Support Their CAL-Card Purchases

During our investigation, we reviewed a sample of CAL-Card transactions from June 2024 through May 2025, and we identified some receipts that Employees A and B submitted that did not appear to be original receipts issued by the vendors. We contacted several vendors and confirmed that some of the receipts we obtained were not the receipts that they had issued for the transactions we were investigating. Both Employees A and B confirmed during interviews that they had created the receipts themselves to support their purchases and that they had not submitted original documentation. By doing so, Employees A and B violated the SCM, which requires CAL‑Card holders to reconcile statement transactions to receipts and supporting documentation, and circumvented controls designed to protect the State from improper purchases. As Table 2 shows, we identified 12 receipts totaling $40,050.28 that Employees A and B created and submitted, representing them as original documents.

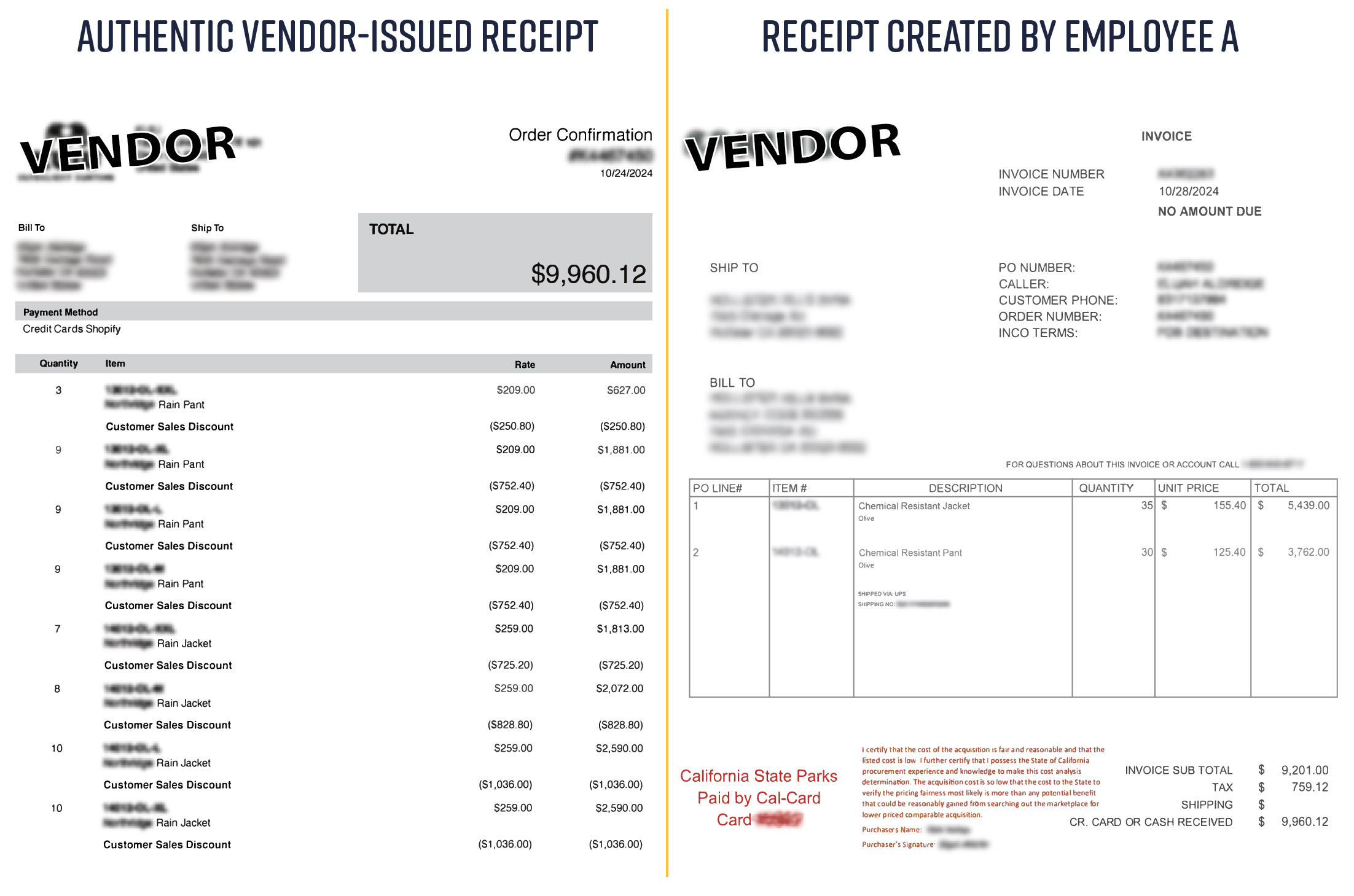

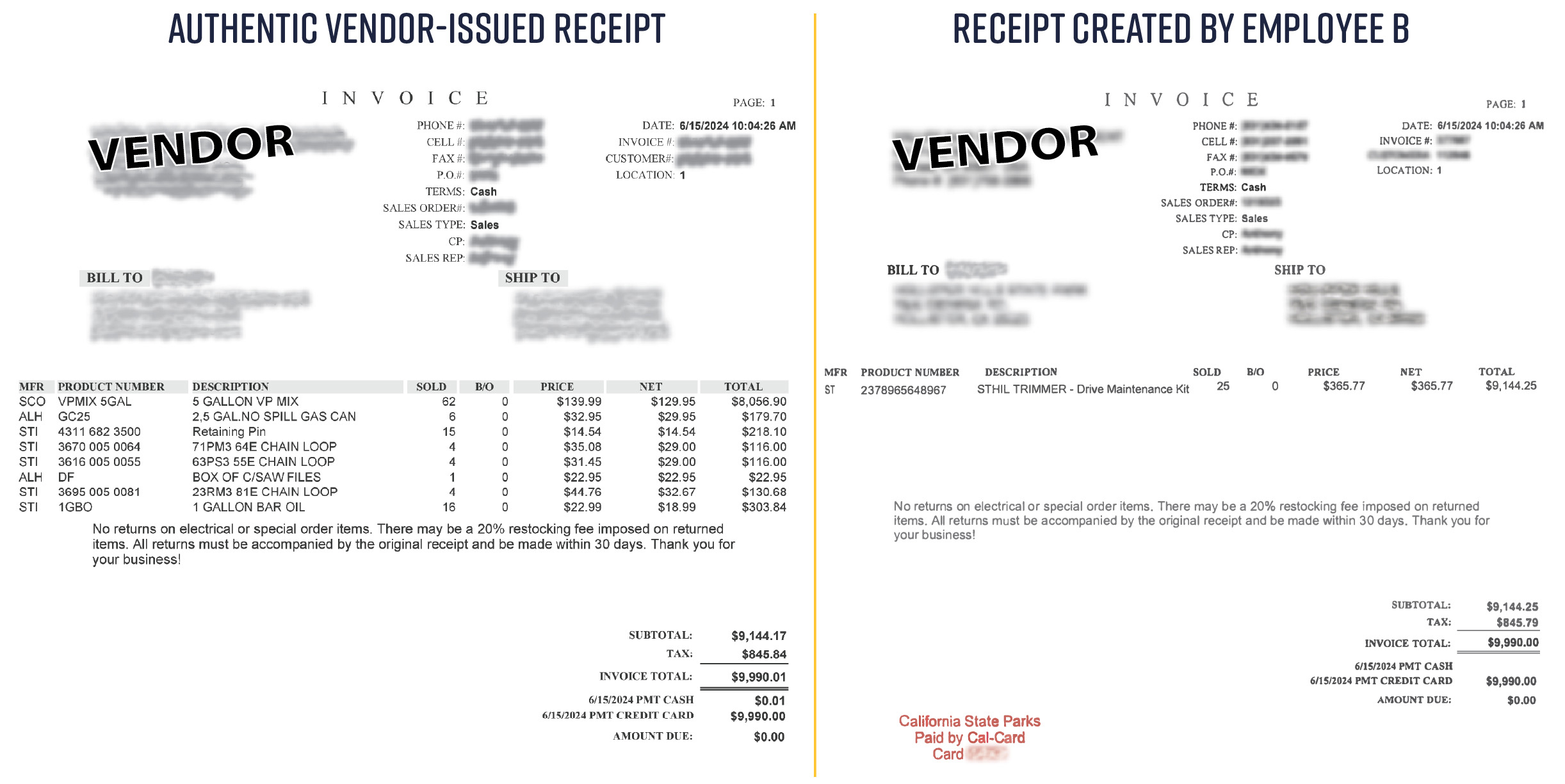

Employee A acknowledged that he created or altered receipts that he submitted to support his CAL-Card purchases. He told us that he created three receipts for purchases that he or others made at Vendor C, a vendor that sells sunglasses and other eyewear, because he did not receive an itemized receipt for the purchases. Employee A also explained that he altered some of the receipts from Vendor D, a vendor that sells outdoor gear, because he was unable to obtain an itemized receipt from the vendor. Employee A also admitted to having altered a receipt by adding the term “chemical resistant” to the original document, as Figure 9 shows. This type of alteration could affect more than just State Park’s ability to reconcile CAL‑Card purchases because it could put peoples’ health at risk. He initially informed us that he did not know if the items were rated for spraying herbicide but later stated that he believed that because the items were water resistant that they were also chemical resistant and appropriate for use when spraying herbicide. Vendor D confirmed to us that it does not advertise its items as chemical resistant.

Figure 9

Example of a Re-Created Receipt From Vendor D

Source: Comparison of receipt Employee A submitted to State Parks and receipt Vendor D provided.

Figure 9 shows an example of a receipt Employee A created compared to the authentic vendor issued receipt. The total amount of each of the receipts is $9,960.12 but the vendor issued receipt displays eight itemized products while the receipt Employee A created shows two items with a description indicating chemical resistant jacket and chemical resistant pant. Some of the information on both receipts has been blurred. The source of this information is a comparison of receipt Employee A submitted to State Parks and a receipt Vendor D provided.

Employee A informed us that he also altered two receipts from Vendor E because the amounts on the receipts he received from the vendor were for the full amounts of the orders and did not match the multiple smaller charges that appeared on his CAL‑Card statement that occurred when individual items or groups of items shipped. He claimed to have created the receipts to support the charges, but Employee A was unable to recall why one of the receipts that he presented from Vendor B contained the same Federal Express tracking number as an earlier receipt he submitted, and we concluded that he simply used the same tracking number when he created the receipt. Finally, Employee A told us that he was sure that he had created additional receipts to support other purchases he had made.

Employee B acknowledged that he created two receipts for purchases from Vendor A, which he submitted to support his CAL-Card purchases. He explained that he created receipts for large purchases from Vendor A, as Figure 10 shows, to consolidate the items he purchased to make the data entry easier for procurement staff. He denied creating receipts for purchases from other vendors to support his CAL-Card statement.

Figure 10

Example of a Re-Created Receipt From Vendor A

Source: Comparison of receipt submitted to State Parks and the receipt in Employee B’s email.

Figure 10 shows an example of a receipt Employee B created compared to the authentic vendor issued receipt. The total amount of each receipt is $9,900 but the vendor issued receipt displays eight itemized products while the receipt Employee B created displays one product that is different than the eight products listed on the authentic receipt. Some of the information on both receipts has been blurred. The source of this information is comparison of receipt submitted to State Parks and the receipt in Employee B’s email.

We found that both employees’ explanations lacked credibility because their actions were inefficient, causing more work for themselves, and they could have easily resolved the issue with better communication with procurement staff; however, we did not find any evidence that they personally benefited from these transactions or that they intended to defraud the State. Nevertheless, even without such evidence, the employees’ disregard for established controls is concerning because it could easily lead to improper purchases or even theft.

A CAL-Card Holder Allowed Other State Parks Employees to Use His CAL-Card to Make Purchases

Employee A violated the SCM when he permitted other State Parks employees to use his CAL-Card to make purchases on at least three separate occasions. Employee A confirmed that other employees used his CAL-Card to make three purchases totaling $6,556 at Vendor C. Employee A could not recall which employee or employees he allowed to use his CAL-Card, but he confirmed that he did not receive itemized receipts from them for these purchases and could not remember how he ensured that the receipts he created were accurate. As a result, he did not know whether the receipts he created accurately reflected the number and type of items that employees purchased.

State Parks Employees Circumvented Other Controls Designed to Protect the State and Its Assets

Employees A and B violated the SAM when they did not add to inventory the equipment they purchased that cost more than $400, which increases the risk that these assets might become lost or stolen. As Table 3 shows, Employees A and B purchased 21 items, each valued at more than $400, that they did not properly include on the inventory list as of July 2025. The total value of the items is $25,470.

Employees A and B did not follow state policy that requires the separation of procurement duties. SAM states that employees should not be involved in more than one of the following functions for any transaction: authorization, custody of assets, recording transactions, and reconciliations of purchases. They did not follow a process that separated purchasing duties, and the person who placed orders also received those orders and verified their accuracy. They retained custody of assets that exceeded $400 without adding those items to the inventory. Moreover, it does not appear that State Parks critically reviews monthly CAL-Card reconciliations for accuracy because a witness confirmed that Employee A submitted the same receipt for multiple purchases on at least two occasions.

In general, the evidence we collected for this investigation indicates an attitude of disregard for controls designed to protect the State and its assets. This is particularly concerning, given the potentially high-value items that Employees A and B purchased that could potentially be adapted for personal use and were not in State Parks’ inventory list. Given our findings, a reasonable risk exists that employees will misuse or waste state resources or even that state-owned assets may become lost or stolen.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activities we identified and to prevent those activities from recurring, Parks and Recreation should take the following actions:

- Review the receipts that Employees A and B submitted, ensure that the State has received all items that these employees purchased, that all of these purchased items are appropriate, and that the items have been inventoried where required.

- Take appropriate corrective action for those involved and ensure that they receive training on and are familiar with State Parks policy and state law related to procurement.

- Correct the control deficiencies we identified, including adding all assets that cost more than $400 to the inventory list and creating a process for the separation of duties in purchasing.

- Provide training to all relevant managers on the applicable policies, laws, and internal controls related to purchasing and procurement.

Agency Response

State Parks informed us that after receiving our report, it initiated its own investigation, which will include a thorough review of purchases made by the employees to confirm that the items purchased are appropriate and are properly tagged and inventoried. It has suspended the employees’ CAL-Card privileges until the investigation is complete and reported that its property custodian in the employees’ district will verify that purchased assets are properly inventoried each month. Finally, it is requiring all staff in the district with CAL-Card responsibilities, including all supervisors and managers, to participate in refresher training on the applicable policies, laws, and internal controls related to purchasing and procurement.

Although State Parks stated that it believes its staff adhered to state policies regarding separation of duties, we found that Employees A and B did not. For example, both employees told us that they did not get preapproval for their purchases, meaning they authorized their own purchases. Employees A and B were also the individuals responsible for receiving the orders they made and verifying their accuracy. SAM requires separation of duties for functions of authorization, custody of assets, recording transactions, and reconciliations.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

December 12, 2025

- The Whistleblower Act can be found in its entirety in Government Code sections 8547 through 8548.5. It is available online at http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. ↩︎

- Although the employee began the leave of absence in July 2022, his timesheets indicated that he worked several days in October 2022, November 2022, January 2023, and February 2023. ↩︎

- The law defines frequently as 72 nights over 12 months or 36 nights over 3 months. ↩︎