2024-114 State Health Care Staffing Contracts

Contract Workers Are a Small but Growing Proportion of Three State Facilities’ Workforces

Published: December 4, 2025Report Number: 2024-114

December 4, 2025

2024‑114

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and its Salinas Valley State Prison facility, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and its Porterville Developmental Center facility, and the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) and its Atascadero State Hospital facility. Our assessment focused on the three departments’ use of health care staffing contracts at these facilities, and we determined that although contract workers make up a small portion of medical and mental health staffing, the facilities have increasingly used them to address their growing number of staff vacancies.

Since July 2019, vacancy rates have increased to 30 percent at Atascadero, 36 percent at Porterville, and more than 50 percent at Salinas Valley. Although the facilities have engaged in multiple recruitment strategies, they have not evaluated the success of their efforts to determine which are most effective. To help address vacancies, each facility has significantly increased its use of contract workers: Atascadero by 79 percent, Porterville by 172 percent, and Salinas Valley by 46 percent. Contract workers generally cost the State more than state employees in the same job classifications, and the shorter tenure of contract workers presents challenges for facilities because of the training necessary to ensure that the contract workers are prepared to provide appropriate care to the facilities’ patient populations.

The many staff vacancies have resulted in each facility realizing significant savings from fiscal year 2019–20 through 2024–25: about $247 million for Atascadero, $188 million for Salinas Valley, and $157 million for Porterville. Nonetheless, neither DSH nor DDS has required staff to evaluate staffing needs annually. Further, none of the three agencies require their facilities to report whether they are meeting shift-staffing minimums, which are critical to ensuring the provision of legally required levels of care. Because of the decades-long difficulties the facilities have had in filling vacant health care positions and a current and projected health care professional shortage, the State should consider facilitating a statewide campaign to draw medical and mental health care workers to California’s civil service.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CalHR | California Department of Human Resources |

| CCHCS | California Correctional Health Care Services |

| CDCR | California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

| CHA | California Hospital Association |

| DDS | Department of Developmental Services |

| DSH | Department of State Hospitals |

| FTE | Full-time equivalent |

| HCAI | Department of Health Care Access and Information |

| HRSA | Health Resources and Services Administration |

| SAM | State Administrative Manual |

| SCO | State Controller’s Office |

| SPB | State Personnel Board |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), and the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) have a responsibility to provide medical and mental health care to individuals who are incarcerated in or committed to the facilities they oversee. To determine the extent to which these departments rely on contract workers rather than state employees to provide this care, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed us to examine staffing levels at three facilities: the Department of State Hospitals‑Atascadero (Atascadero), which DSH oversees; the Porterville Developmental Center (Porterville), which DDS oversees; and Salinas Valley State Prison (Salinas Valley), which CDCR oversees. Our review determined the following:

The Three Facilities We Reviewed Have Increasingly Struggled to Fill Vacant Positions

Over the past five years, vacancy rates at all three facilities we reviewed have increased. As of fiscal year 2023–24, the vacancy rate was just over 30 percent at Atascadero, 36 percent at Porterville, and more than 50 percent at Salinas Valley. Most of these vacant positions were in nursing and mental health classifications. Facility staff and employee bargaining unit representatives specifically identified the high‑risk nature of the work, a shortage of health care professionals, and low pay as factors contributing to the high number of vacancies. Facility staff also asserted that they must compete with other state facilities and private hospitals for the same limited pool of potential job candidates. Although the facilities have engaged in a number of recruitment strategies, they generally do not evaluate the success of these efforts to determine which are most effective. Given the decades‑long difficulties the facilities have had in filling vacant health care positions and the current and projected health care professional shortage, the State should consider facilitating a statewide campaign to draw medical and mental health care workers to California’s civil service.

To Address Their Vacancies, the Three Facilities Have Increased Their Use of Contract Workers

Contract workers make up a small portion—from 4 percent to 10 percent—of each facility’s medical and mental health care staffing. However, to address ongoing vacancies, each facility has significantly increased its use of contract workers over the past five years: Atascadero by 79 percent, Porterville by 172 percent, and Salinas Valley by 46 percent. Nearly all contract worker classifications cost the facilities more per hour than their state civil service counterparts, even after taking into account the nonwage costs associated with state civil service employment, such as benefits. Although the contract workers we reviewed possessed the necessary licenses and certifications to work within their classifications, they generally had significantly shorter tenures at each facility than state employees in the same classifications. These shorter tenures can present a challenge for facilities because of the training necessary to ensure that the contract workers are prepared to work with their patient populations and provide appropriate care.

CDCR, DDS, and DSH Have Not Taken Necessary Steps to Ensure That Their Facilities Have Appropriate Staffing Levels

By budgeting staff positions appropriately, departments can request that the Legislature fund the staff necessary to meet their facilities’ operational needs, while not requesting positions they do not require. However, from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25, the three facilities we reviewed had a significant number of vacant positions that they did not cover with either state overtime or contract workers. Moreover, each facility realized significant savings from these vacant positions over the six years: about $247 million for Atascadero, $188 million for Salinas Valley, and $157 million for Porterville. Nonetheless, neither DSH nor DDS has established policies and procedures to ensure that their process for staff budgeting is adequate, such as by including a requirement for staff to evaluate staffing needs at least annually. In addition, DSH, DDS, and CDCR have not formalized a process for facilities to report whether they are meeting shift‑staffing minimums, which are critical to ensuring the provision of legally required levels of care.

Other Areas We Reviewed

In addition, we reviewed staffing logs from the three facilities and found that they used state employees to provide the majority of patient care but filled in shifts with contract workers as necessary. We also conducted interviews with frontline workers to gain insight into their workplace concerns.

To address these findings, we recommended a number of recruiting and retention strategies that the departments and facilities should implement, including exploring the feasibility of maximizing flexible shifts and streamlining their hiring processes. We further recommended that DSH and DDS develop comprehensive policies and procedures for their annual budgeting processes that include the requirement that staff evaluate staffing needs annually and seek adjustments to position authority—the number of positions authorized in the state budget—for each facility as necessary. In addition, we recommended that the departments require their facilities to track, tabulate, and report instances when they fall short of shift‑staffing minimums. Finally, we recommended that the Legislature consider requiring the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) to facilitate a statewide, cross‑agency collaboration to recruit medical and mental health care staff into California’s civil service and to locations where it is especially difficult to recruit state employees.

Agency Comments

CDCR agreed with our recommendations. DDS and DSH generally agreed with our recommendations, but DDS disagreed with our recommendation that it require its facilities to track and report whether they are meeting required shift-staffing minimums, and DSH disagreed with our recommendation that it evaluate whether offering affordable housing options would improve Atascadero’s ability to recruit new state employees.

Introduction

Background

The three health care facilities we reviewed—Atascadero, Porterville, and Salinas Valley—house individuals who are incarcerated or institutionalized because the courts or those with jurisdiction over those individuals have determined they are a danger to themselves or others, or that they are incompetent to stand trial. State and federal laws require each of these facilities to provide medical and mental health care to the individuals they house. Specifically, the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and California’s Lanterman‑Petris‑Short Act give individuals who are involuntarily detained the right to prompt medical and mental health care. These laws apply to individuals who are committed to DSH, which oversees Atascadero, and to DDS, which oversees Porterville. Further, the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment of incarcerated individuals. This amendment applies to individuals who are subject to the jurisdiction of CDCR, which oversees Salinas Valley. Individuals subject to the jurisdiction of CDCR include incarcerated individuals who CDCR sends to DSH for psychiatric stabilization. The courts have interpreted a failure to provide adequate medical and mental health care to incarcerated individuals as cruel and unusual punishment.

The Three Facilities Serve Different Populations

The three facilities we reviewed are all in Central California, as Figure 1 shows. Each maintains different licensure types, enabling it to provide medical and mental health care specific to the needs of its population. Atascadero is an acute psychiatric hospital and an intermediate care facility under DSH. It has the largest capacity of the three health care facilities we reviewed, with 1,275 licensed beds. Its all‑male patient population consists mostly of criminal offenders with severe mental illnesses, some of whom were found not guilty by reason of insanity or incompetent to stand trial. Thus, the courts involuntarily committed—either criminally or civilly—these individuals to Atascadero for treatment. A small number of Atascadero’s patients have not been charged with a crime; rather, they are treated under a conservatorship agreement because the courts have determined that their mental illnesses represent a danger to themselves or others.

Figure 1

The Three Central California Facilities Provide Residential Care to Populations With Specific Needs

Source: Websites for DDS, DSH, CDCR, Atascadero, Porterville, Salinas Valley, and California Department of Public Health facility licensing.

A map of California shows the three auditees in Central California.

In the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation callout bubble, Salinas Valley State Prison is located in Monterey County. Its license type is a Correctional Treatment Center. It has 264 licensed beds. Its population is nearly 2500. Its residents are incarcerated adults.

In the Department of Developmental Services callout bubble, Porterville Developmental Center is located in Tulare County. Its license types are General Acute Care Hospital, Intermediate Care Facility/Developmentally Disabled (ICFDD), ICFDD-Secure Treatment Program (ICFDD-STP). It has 607 licensed beds from 17 acute, 121 ICFDD, and 469 ICFDD-STP. Its population is more than 200. Its residents are developmentally disabled adults.

In the California Department of State Hospitals callout bubble, the Department of State Hospitals-Atascadero is in San Luis Obispo County. Its license types are acute psychiatric hospital and intermediate care facility (ICF). It has 1275 licensed beds from 311 acute and 964 ICF. Its population is more than 1000. Its residents are adults with severe mental illnesses.

Porterville is licensed as a general acute care hospital and as an intermediate care facility for developmentally disabled individuals. The courts criminally or civilly commit individuals to Porterville when the courts have determined they are incompetent to stand trial or pose a danger to themselves or others. DDS oversees the Porterville facility, which has 607 licensed beds. Although Porterville has the physical space to accommodate 607 patients, state law only allows individuals to be admitted to the facility when the population falls below 211 persons.1

Salinas Valley is a state prison that houses incarcerated adults. Within the prison, CDCR, through its California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS) division, operates a licensed correctional treatment center with a mental health treatment program. Although Salinas Valley is the largest facility we reviewed by total population, it has the least number of licensed health care beds at 264 because it is not a hospital and only a portion of the facility is designated for medical and mental health care.

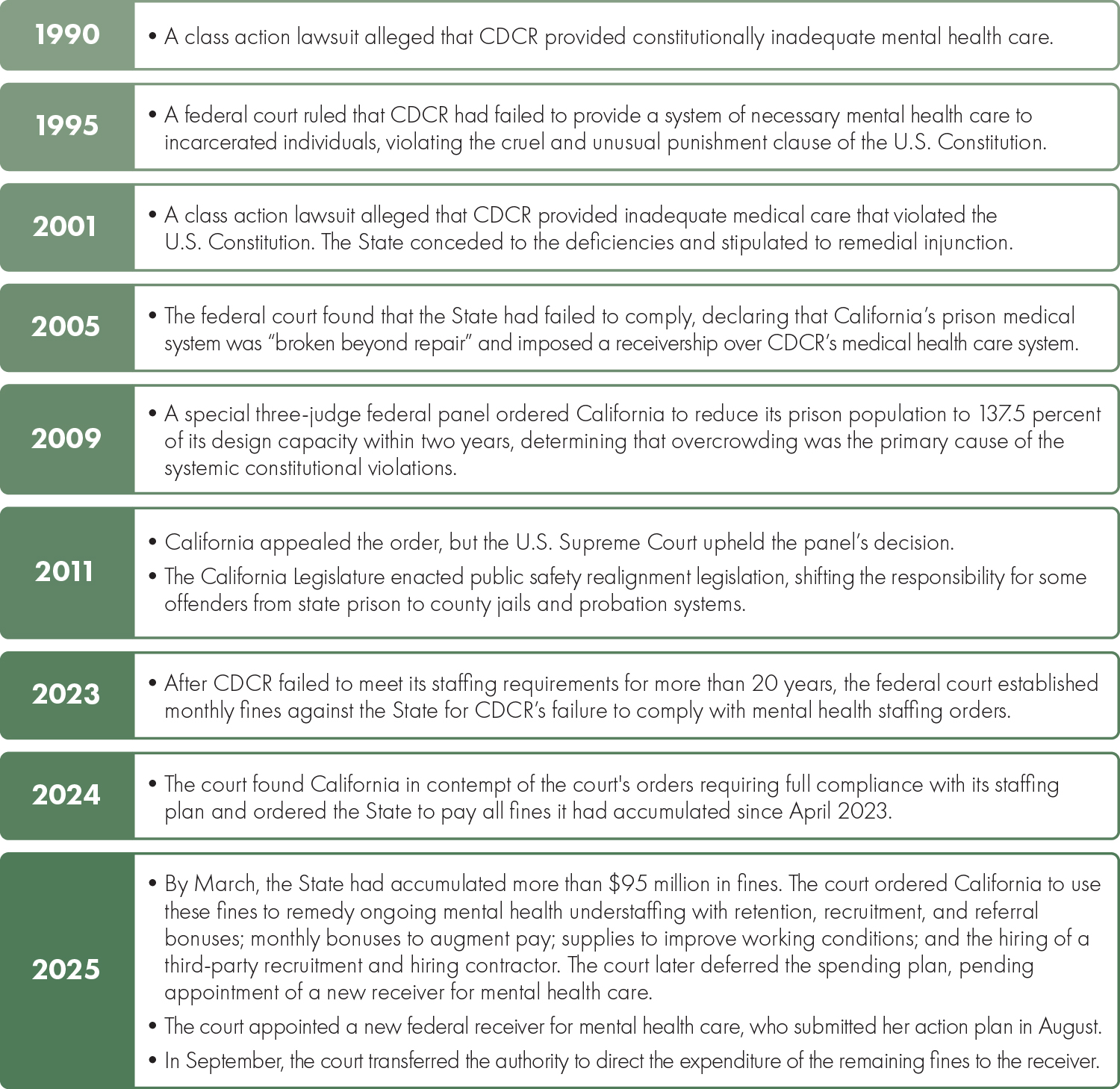

All Three Departments Have Been Involved in Litigation Regarding Medical and Mental Health Care Staffing

Dating back decades, the State has been involved in a number of lawsuits regarding its failure to meet minimum medical and mental health care staffing requirements at health care facilities that state agencies operate. In particular, ongoing federal court orders mandate CDCR and its facilities to fill 90 percent or more of certain mental health care positions. In 2023, the court ordered the State to pay monthly fines for noncompliance with mandated mental health staffing levels. As of 2025, CDCR had incurred more than $95 million in accumulated fines, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2

For 35 Years, CDCR Has Not Provided Adequate Medical and Mental Health Care

Source: Various court documents related to Coleman v. Brown and Plata v. Newsom court cases.

• 1990: A class action lawsuit alleged that CDCR provided constitutionally inadequate mental health care.

• 1995: A federal court ruled that CDCR had failed to provide a system of necessary mental health care to incarcerated individuals, violating the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the U.S. Constitution.

• 2001: A class action lawsuit alleged that CDCR provided inadequate medical care that violated the U.S. Constitution. The State conceded to the deficiencies and stipulated to remedial injunction.

• 2005: The federal court found that the State had failed to comply, declaring that California’s prison medical system was “broken beyond repair” and imposed a receivership over CDCR’s medical health care system.

• 2009: A special three-judge federal panel ordered California to reduce its prison population to 137.5 percent of its design capacity within two years, determining that overcrowding was the primary cause of the systemic constitutional violations.

• 2011: California appealed the order, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the panel’s decision. Also, the California Legislature enacted public safety realignment legislation, shifting the responsibility for some offenders from state prison to county jails and probation systems.

• 2023: After CDCR failed to meet its staffing requirements for more than 20 years, the federal court established monthly fines against the State for CDCR’s failure to comply with mental health staffing orders.

• 2024: The court found California in contempt of the court’s orders requiring full compliance with its staffing plan and ordered the State to pay all fines it had accumulated since April 2023.

• 2025: By March, the State had accumulated more than $95 million in fines. The court ordered California to use these fines to remedy ongoing mental health understaffing with retention, recruitment, and referral bonuses; monthly bonuses to augment pay; supplies to improve working conditions; and the hiring of a third-party recruitment and hiring contractor. The court later deferred the spending plan, pending appointment of a new receiver for mental health care. The court appointed a new federal receiver for mental health care, who submitted her action plan in August. In September, the court transferred the authority to direct the expenditure of the remaining fines to the receiver.

Both DDS and DSH have also been involved in litigation for failing to provide adequate mental health care staffing. Specifically, a 1981 court order required the facilities that the two departments oversee to post in a place that is visible to level‑of‑care staff of each unit and ward their minimum shift‑staffing requirements. In addition, the court order required that the facilities track, tabulate, and report quarterly to their department headquarters the shifts and number of staff by which they fell short. The court order established a best practice to ensure accountability, increase transparency, and allow for the appropriate oversight of mandatory staffing ratios.

The Civil Service Mandate Requires State Agencies to Justify Their Use of Contract Workers Instead of State Employees

A civil service mandate generally prohibits state agencies from contracting with private entities to perform work that the State has historically and customarily performed using the state civil service employees (state employees). This mandate essentially requires state agencies to hire state employees rather than contracting for services unless exempted under state law. Nonetheless, state law provides some exceptions under which agencies may use personal services contracts. In this report, we discuss two provisions of Government Code Section 19130, specifically paragraphs (3) and (10) of subdivision (b) of that section. The first provision applies when the contracted services are not available within civil service. The second applies when the services are of such an urgent, temporary, or occasional nature that the delay inherent in hiring under civil service would frustrate their very purpose.

Personal services contracts are subject to oversight by the State Personnel Board (SPB). The SPB enforces civil service statutes, makes determinations regarding probationary periods and classifications, adopts other civil service rules, and reviews disciplinary actions. In addition, if a state agency cites one of the above‑described provisions as justification when entering a personal services contract, any employee organization that represents state employees can request the SPB to review that contract to determine its adequacy. For example, in 2019, at the request of an employee organization, the SPB reviewed a CDCR contract for six contracted classifications. The SPB approved the contract for two of the classifications but disapproved it for the other four, finding that CDCR either did not demonstrate reasonable and good faith efforts to recruit civil service employees or failed to establish the needed number of civil service positions in those classifications.

Audit Results

- The Three Facilities We Reviewed Have Increasingly Struggled to Fill Vacant Positions

- To Address Their Vacancies, the Three Facilities Have Increased Their Use of Contract Workers

- CDCR, DDS, and DSH Have Not Taken Necessary Steps to Ensure That Their Facilities Have Appropriate Staffing Levels

The Three Facilities We Reviewed Have Increasingly Struggled to Fill Vacant Positions

Key Points

- Vacancy rates at all three of the facilities we reviewed have increased since fiscal year 2019–20. As of fiscal year 2023–24, their vacancy rates for health care positions ranged from just over 30 percent at Atascadero to more than 50 percent at Salinas Valley. Their vacancy rates for psychiatrist and other mental health positions were especially high—often exceeding 50 percent.

- The facilities face several barriers to recruiting new state employees. Each is located in a small city, surrounded by rural areas, in a county with a shortage of health care professionals. The facilities must compete with private sector hospitals, contract staffing agencies, and other nearby state facilities for a limited number of trained job candidates.

- Although the facilities have taken some steps to broaden their recruiting efforts, they could take additional action to make themselves more attractive to potential job candidates, such as offering more scheduling flexibility. The facilities and the departments that oversee them evaluate the results of certain recruitment efforts but could perform additional analysis to determine which of those efforts are the most effective.

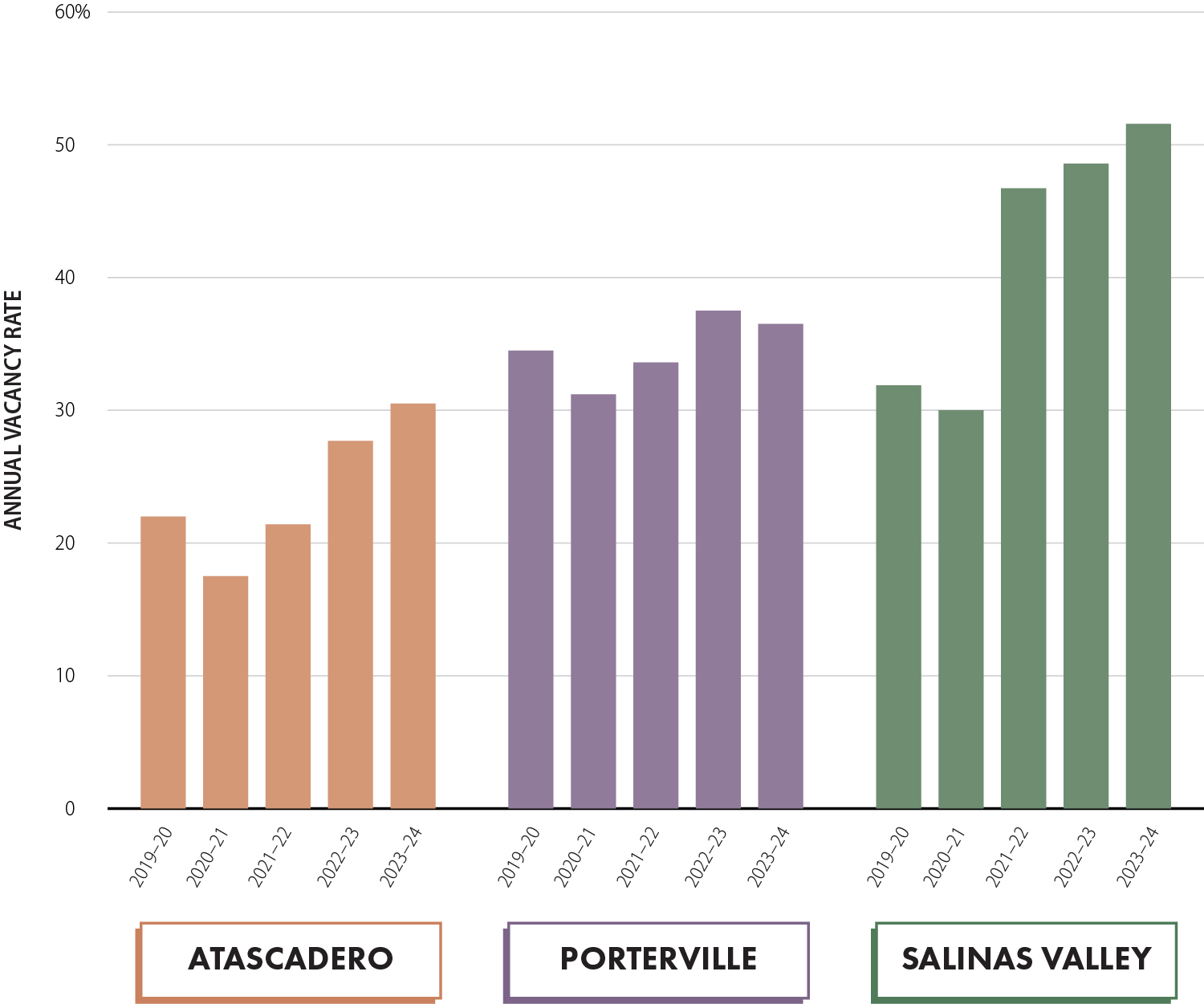

In Recent Years, All Three Facilities Have Experienced Significant, Growing Vacancy Rates

Overall, vacancy rates for medical and mental health positions at each of the three facilities we reviewed increased from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24. Vacancy rates can be impacted by a variety of factors, including an increased or decreased number of authorized positions, difficulty filling positions, and staff attrition. As Figure 3 shows, all three facilities had a vacancy rate of 30 percent or more during fiscal year 2023–24, with Salinas Valley having the highest vacancy rate. Salinas Valley’s vacancy rate for medical and mental health care employees increased by 62 percent during our audit period, with more than half of its medical and mental health positions vacant in fiscal year 2023–24. Atascadero had a vacancy rate that was a little more than 30 percent in fiscal year 2023–24, a nearly 39 percent increase from fiscal year 2019–20. Specifically, from fiscal years 2021–22 to 2023–24, Atascadero increased its authorized positions by more than 50, and during that same time frame it lost more than 90 staff to attrition. Although Porterville’s vacancy rate increased only by roughly 6 percent during our review period, 36 percent of its medical and mental health positions were vacant during fiscal year 2023–24.

Figure 3

The Three Facilities’ Vacancy Rates for Medical and Mental Health Care Positions Increased Overall

Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2023–24

Source: Analysis of State Controller’s Office (SCO) vacancy data, Porterville’s monthly staffing reports, and CDCR’s monthly staffing reports.

Column charts for the three facilities between fiscal years 2019 to 2020 through 2023 to 2024.

At Atascadero, the vacancy rate in 2019 to 2020 was over 20 percent. In 2020 to 2021, the vacancy rate decreased to under 20 percent. In 2021 to 2022 the vacancy rate increased to over 20 percent. In 2022 to 2023, the vacancy rate increased to near 30 percent. In 2023 to 2024 the vacancy rate increased to over 30 percent.

At Porterville, the vacancy rate in 2019 to 2020 was between 30 and 40 percent. In 2020 to 2021, it decreased to just over 30 percent. In 2021 to 2022 it increased to between 30 and 40 percent. In 2022 to 2023, it increased just under 40 percent. In 2023 to 2024 it decreased slightly still above 30 percent.

At Salinas Valley, the vacancy rate in 2019 to 2020 was above 30 percent. In 2020 to 2021, it decreased to 30 percent. In 2021 to 2022, it increased to between 40 and 50 percent. In 2022 to 2023, it increased just under 50 percent. In 2023 to 2024, it increased over 50 percent.

To evaluate trends and compare staffing levels among the facilities, we judgmentally grouped similar job classifications into five main groupings—mental health, nursing, primary care, psychiatry, and other—as the text box shows. As Table 1 indicates, during fiscal year 2023–24, positions in the psychiatry grouping had the highest vacancy rate at Atascadero and the second highest vacancy rate at Porterville and Salinas Valley. During fiscal year 2023–24, Salinas Valley and Atascadero also had high vacancy rates in the other mental health grouping, which includes psychologists and social workers. Porterville, on the other hand, experienced its highest vacancy rate during fiscal year 2023–24 in the primary care grouping.

We Categorized Health Care Job Classifications Into Five Groupings

Mental Health: Psychologists, social workers, and marriage and family therapists.

Nursing: Registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, certified nursing assistants, and psychiatric technicians.

Primary Care: Physicians, surgeons, medical residents, and physician assistants.

Psychiatry: Psychiatrists.

Other: All other medical or mental health professionals, including behavior specialists, dentists, dietetic technicians, lab assistants, pharmacists, physical therapists, radiologic technologists, rehabilitation therapists, respiratory care practitioners, and speech pathologists.

Source: Auditor generated from review of facility classifications.

Note: The job classifications we list here are just a few of the nearly 200 classifications we included in our review.

Although the nursing grouping did not have the highest vacancy rates at any of the three facilities, vacancies in this grouping largely drove all of their overall vacancy rates because about two‑thirds or more of each facility’s medical and mental health care employees work in nursing classifications. Consequently, vacancies in the nursing grouping accounted for 65 percent or more of all vacancies at each of the three facilities during fiscal year 2023–24. In fact, in fiscal year 2023–24, nursing vacancy rates and total vacancy rates at each of the facilities were within 2 percentage points of each other.

Although employee hiring and separation trends were stable for most job classification groupings throughout our audit period, they fluctuated significantly for the nursing grouping at each of the three facilities we reviewed, as Figure 4 shows. Porterville’s executive director stated that many of its staff in the nursing grouping either left when it closed its general treatment area in 2019 or during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Salinas Valley staff stated that the facility eliminated its medical technical assistant classifications in the nursing group in fiscal year 2019–20 and that many of those employees transitioned to correctional job classifications because of higher rates of pay. Although the departments and facilities focused their perspective on challenges in hiring when asked about vacancies, we noted that, despite their recruiting efforts, attrition often outpaced hiring during our audit period, an issue we discuss later in this report. We present the details of vacancies, hiring, separations, and net gains and losses of state employees by facility, position type, and fiscal year in Table B.1 and Table B.2 of Appendix B.

Figure 4

Net Gains and Losses of Nursing Staff Fluctuated Considerably at All Three Facilities

July 2019 Through December 2024

Source: SCO data.

Note: Net gains and losses are based on appointments and separations. Appointments include hires and changes in job classification, while separations include separations from the facility and changes in job classification. If an individual changed from one job classification to another, but remained within the same job category, they were counted as both an appointment and a separation, resulting in no net gain or loss in that grouping.

Three line charts for each facility depicting erratic net change in Nursing staff from July 2019 through December 2024.

At Atascadero, from July 2019 to July 2020 there was an increase of 80 staff. From July 2020 to July 2021, Nursing staff decreased to around 70. From July 2021 through July 2023, Nursing staff increased to just under 80. By July 2023, Nursing staff decreased to just under 60. In July 2024, it increased just under 80. By December 2024, it decreased to around 70. During this same time, the range for all other groups fluctuated less both over and under 0.Three line charts for each facility depicting erratic net change in Nursing staff from July 2019 through December 2024.

At Porterville, from July 2019 to July 2020 there was a decrease in Nursing staff to between negative 20 and negative 25. By July 2021, Nursing staff increased to between negative 15 and negative 10. In July 2022, Nursing staff decreased again to just over negative 15. By July 2023, it increased to nearly 5. From July 2023 to July 2024, Nursing staff decreased to more than negative 15. By December 2024, it decreased to just over negative 20. The range for all other groups remained positive.

At Salinas Valley, from July 2019 to July 2020 there was a net negative change by nearly negative 60 Nursing staff. By July 2021, there was a there was a slight positive net change in staff. By July 2022, there was a net negative change in Nursing staff to around negative 70. By July 2023, there was a net negative change in Nursing staff to around negative 90. This remained steady to July 2024. By December 2024, there was a slight net positive change to just over negative 80 Nursing staff.

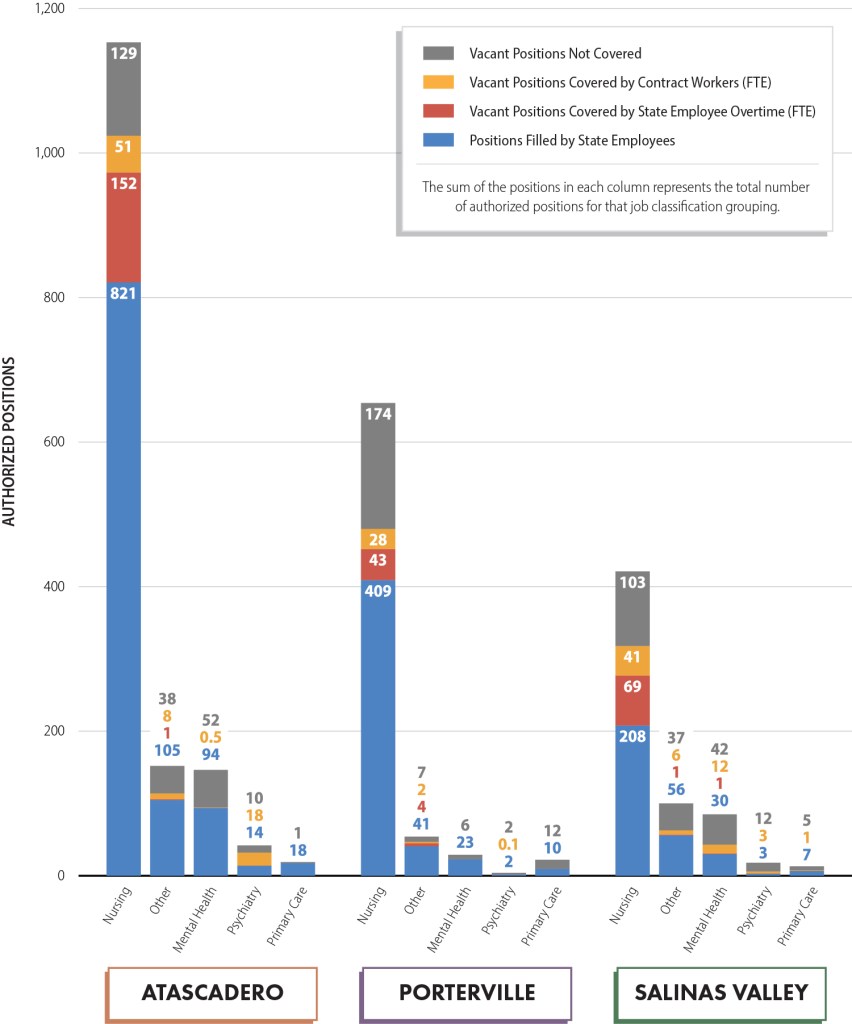

Staff at each department asserted that they have used a mix of state employee overtime and contract workers to cover their ongoing vacancies. However, even after accounting for overtime and contract workers’ hours, each facility still had uncovered vacant positions throughout our audit period. Figure 5 shows the number of full‑time equivalent (FTE) positions that were not covered by state employee overtime or contract workers during fiscal year 2023–24. We discuss the departments’ budgeting of positions at the facilities in the final section of this report.

Figure 5

Facilities Used Overtime and Contract Workers to Cover Vacant Authorized Positions

Fiscal Year 2023–24

Source: State budget documents, SCO data, Porterville’s monthly staffing reports, CDCR’s monthly staffing reports, and facility invoice data.

Note: Facilities use a combination of voluntary and mandatory overtime, as well as contract workers and retired annuitants, to cover some unfilled shifts caused by vacant positions. We calculated the number of state employee overtime and contract worker full‑time equivalent (FTE) positions by dividing the relevant number of hours worked by 2,080 (52 weeks times 40 hours per week). State employee overtime FTE positions reflect all state employee overtime hours, while contract worker FTE positions reflect all contract worker hours, including regular time and overtime. Because the vacancy data contains only established positions, these results do not include the number of FTE positions filled by retired annuitants and some other temporary positions.

A stacked column chart showing authorized positions for Atascadero, Porterville, and Salinas Valley in the Nursing, Other, Mental Health, Psychiatry, and Primary Care categories. The sum of the positions in each column represents the total number of authorized positions for that job classification grouping. Vacant positions covered by state employee overtime and vacant positions covered by contract workers are both calculated as full-time equivalent (FTE).

At Atascadero, Nursing had 821 positions filled by state employees, 152 vacant positions covered by state employee overtime, 51 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 129 vacant positions not covered. In the Other grouping, there were 105 positions filled by state employees, 1 vacant position covered by state employee overtime, 8 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 38 vacant positions not covered. In the Mental Health grouping, there were 94 positions filled by state employees, 0.5 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 52 vacant positions not covered. In the Psychiatry grouping there were 14 positions filled by state employees, 18 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 10 vacant positions not covered. In the primary care grouping there were 18 positions filled by state employees and 1 vacant position not covered.

At Porterville, in the Nursing grouping there were 409 positions filled by state employees, 43 vacant positions covered by state employee overtime, 28 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 174 vacant positions not covered. In the Other grouping there were 41 positions filled by state employees, 4 vacant positions covered by state employee overtime, 2 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 7 vacant positions not covered. In the Mental Health grouping there were 23 positions filled by state employees and 6 vacant positions not covered. In the Psychiatry grouping there were 2 positions filled by state employees, 0.1 vacant positions covered by state employee overtime, and 2 vacant positions not covered. In the Primary Care grouping there were 10 positions filled by state employees and 12 vacant positions not covered.

At Salinas Valley, in the Nursing grouping there were 208 positions filled by state employees, 69 vacant positions covered by state employee overtime, 41 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 103 vacant positions not covered. In the Other grouping there were 56 positions filled by state employees, 1 vacant position covered by state employee overtime, 6 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 37 vacant positions not covered. In the Mental Health grouping there were 30 positions filled by state employees, 1 vacant position covered by state employee overtime, 12 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 42 vacant positions not covered. In the Psychiatry grouping there were 3 positions filled by state employees, 3 vacant positions covered by contract workers, and 12 vacant positions not covered. In the Primary Care grouping there were 7 positions filled by state employees, 1 vacant position covered by contract workers, and 5 vacant positions not covered.

The Facilities Face a Number of Barriers When Recruiting New State Employees

Each of the facilities we reviewed faces challenges when recruiting staff, including difficult working conditions, a local shortage of health care professionals, and competition with other public facilities, private hospitals, and contract staffing agencies. However, Atascadero, Porterville, and the departments that oversee them have not conducted salary surveys to determine their competitiveness in the marketplace for health care professionals because, according to staff, they lack the necessary funding and resources.

Challenging Work Environments

The facility staff and employee bargaining unit representatives we spoke with identified the high‑risk nature of the work as one of the primary causes of their ongoing vacancies. For example, in October 2025, a riot at Salinas Valley involving about 90 incarcerated individuals resulted in harm to three incarcerated individuals and to one staff member, who was treated for heat exhaustion. Salinas Valley’s chief of mental health stated that some prospective employees may not be interested in working in such an environment, making recruiting staff more difficult. Atascadero and Porterville have similar work environments. In fact, according to DSH, there were nearly 2,900 patient‑on‑patient assaults and more than 2,500 patient‑on‑staff assaults across all of its hospitals in 2020—the most recent year for which published data is available.

Several of the staff we interviewed at Porterville—the only state‑operated facility that serves individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities who have been deemed a danger to themselves or others—described working in conditions in which they are verbally and physically assaulted regularly. According to Porterville’s bargaining unit president, on‑the‑job injuries have led to retirements for some employees. He also asserted that given the unsafe working conditions because of patients who are sometimes violent, the State should offer employees additional compensation while staff work to make the facility safer.

Shortage of Health Care Professionals

Aside from working conditions, a shortage of health care professionals has contributed to the vacancies at the facilities. In a recent report, the California Hospital Association (CHA) stated that the COVID‑19 pandemic delayed education and training for thousands of health care professionals, postponing their entrance into the workforce. CHA further noted that California’s health care pipeline is struggling to keep pace with the demand for services, that 11 million Californians live in an area without enough primary care providers, and that there is a statewide shortage of nurses, physicians, pharmacists, behavioral health professionals, lab scientists, and physical therapists. In addition, the three facilities cited declining enrollment in psychiatric technician programs as a contributing factor for the high vacancies in these positions. According to CDCR staff who recruit for Salinas Valley, the supply of mental health professionals completing school training programs is not enough to meet demand for those professions. A bargaining unit president at Porterville—a senior psychiatric technician with 18 years of state service—explained that enrollment into psychiatric technician programs has been declining since the pandemic.

Moreover, a 2025 report from the Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI)—which collects, analyzes, and publishes information about California’s health workforce and identifies areas of the State that are experiencing shortages of health professionals—indicates that more than 33 percent of the State’s psychologists, more than 30 percent of its physicians, and more than 20 percent of its registered nurses were age 60 or older. Some of these older professionals are likely to retire within the next two to five years, further affecting the supply of health care professionals. HCAI data also show that all three facilities we reviewed are in areas with a shortage of psychiatrists and licensed mental health providers. As Table 2 shows, HCAI data indicate that Monterey County has a 31 percent shortage of psychiatrists, San Luis Obispo County has a 39 percent shortage, and Tulare County has a 75 percent shortage.

In addition, HCAI data show that each of the three facilities we reviewed is located in one of California’s nursing shortage areas. According to HCAI, it designates an area as having a nursing shortage when there is a shortage of registered nurses, clinical nurse specialists, public health nurses, and psychiatric mental health nurses within one of California’s counties or, for Los Angeles County, one of its eight service planning areas. Of the 65 total service areas in the State, HCAI identified 48 as having a low, medium, high, or severe nursing shortage designation. Tulare County, where Porterville is located, has a medium nursing shortage area designation. Monterey County, where Salinas Valley is located, and San Luis Obispo County, where Atascadero is located, both have a low nursing shortage designation. According to department and facility staff, all three facilities have struggled to find effective ways to overcome these and other barriers, leaving them with small pools of candidates from which to recruit.

Other Geographical Challenges

The three facilities’ locations present additional challenges for recruiting staff. Each of the three facilities is located in a small city, surrounded by rural areas with small populations, which may not be attractive to some medical and mental health care professionals interested in state employment. The city of Atascadero has a population of about 30,000 residents, while the city of Porterville has about 63,000 residents. The city of Soledad, where Salinas Valley is located, has fewer than 25,000 residents. Staff and bargaining unit representatives at the three facilities identified their rural locations as a barrier to recruitment for candidates who may be looking for a more vibrant lifestyle.

Atascadero is also located in an area with a high cost of living, which makes it more difficult to recruit medical and mental health care professionals. The compensation for many of these professionals may not be sufficient to provide a living wage. In San Luis Obispo County, where Atascadero is located, estimates show that an adult with one child needs to earn $99,396 annually before taxes to make a living wage. Based on the hourly rates the State offers on the CalHR website (CalCareers), we estimate that a starting licensed vocational nurse at Atascadero earns about $65,000, a starting radiology technologist about $79,000, and a starting clinical social worker about $110,000 annually. A bargaining unit president for Atascadero stated that the cost of living in the area is a major barrier to recruitment and retention and that some staff have moved to lower‑cost areas and commute to the facility. Staff at Atascadero similarly asserted that some applicants have turned down jobs because of the costs of housing. The average price of a home in Atascadero is about $830,000, while a small one‑bedroom apartment costs about $2,000 per month.

Competition With Other State and Private Health Care Facilities

Despite working in high‑risk environments, the medical and mental health care state employees we interviewed asserted that they are generally paid less and may receive fewer benefits than similar workers in the private sector or at other state facilities. To obtain perspective and understanding of working conditions and staffing challenges at each of the facilities, we conducted interviews with 21 frontline staff across the three facilities and held numerous meetings and interviews with facility staff and management. For example, Atascadero staff attributed psychiatrist vacancies in part to the fact that the private sector and other facilities can offer psychiatrists higher salaries and more flexibility. Specifically, staff at Atascadero indicated that a nearby private hospital offers signing bonuses of $90,000 to new psychiatrists, while Atascadero can only offer its employees no more than $10,000. Staff also explained that the relocation package that the State allows it to offer is minimal compared to those of private institutions.

The three state facilities must also compete with other state facilities for potential employees. Porterville’s workforce manager stated that her facility faces competition from nearby CDCR facilities. She explained that pay differentials allow CDCR to pay state employees higher wages for the same work that they would perform at Porterville.2 In the same vein, CDCR operates 31 adult state prisons across the State and each correctional facility is competing with other correctional facilities for the same job candidates. All three facilities we reviewed stated that competition with other state facilities and private institutions has made it more difficult for them to recruit medical and mental health care professionals. The text box identifies some of the state facilities and private hospitals located near the three facilities.

Each Facility We Reviewed Competes With Other Nearby Facilities for Health Care Staff

Atascadero:

- Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center

- French Hospital Medical Center

Porterville:

- Avenal State Prison

- California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility

- Kern Valley State Prison

- North Kern State Prison

- Wasco State Prison

- California State Prison, Corcoran

Salinas Valley:

- Correctional Training Facility

- Kaiser Permanente

Source: Interviews with facility staff.

Competition With Staffing Agencies

In addition to competing for potential employees with private hospitals and other state facilities, the three facilities must also contend with staffing agencies, which frequently offer contract workers salary ranges that are higher than the State offers, as Table 3 shows. We did identify some exceptions: for instance, the staffing agencies that contract with Porterville offer lower salary ranges than the State does for certified nursing assistants, registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, and psychiatric technicians. However, staffing agencies offered higher ranges of pay than the State did for each of the positions we reviewed at one or more of the facilities.

In addition, many staffing agencies offer contract workers benefits similar to those the State offers to its employees. For example, staffing agencies frequently offer health, dental, and vision insurance; malpractice insurance; and retirement plans, including employer‑sponsored retirement savings plans, such as 401(k)s. Some also offered other benefits, such as voluntary identity theft protection plans, transportation assistance, and employee discount programs.

Human resources staff at Atascadero and Porterville and their respective departments acknowledged that civil service salaries are frequently lower than those offered by staffing agencies and stated that these salary differences can negatively affect their recruitment efforts. To address this issue, staff at these departments and facilities have sometimes sought to obtain additional compensation, such as pay differentials, for state employees. To obtain pay differentials, state departments must submit an employee compensation request to the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR). For example, staff at Atascadero explained that they obtained pay differentials of $400 per month for the facility’s psychiatric technicians. However, staff stated that CalHR has frequently denied their requests for reasons that included a lack of state funding. In contrast to DSH and DDS, staff at CDCR asserted that they did not know how much contract workers at Salinas Valley earn and had no perspective on how the differences in the pay for state employees and contract workers might affect their recruitment efforts.

Despite asserting that the State’s salaries may affect their recruitment efforts, staff from Atascadero, Porterville, and their respective departments acknowledged that they have not conducted a formal salary survey to identify differences in state salaries and contract worker salaries. Staff at the two departments stated there may be a benefit to conducting a survey as it could enhance their position when negotiating salary changes with CalHR; however, they explained that they do not have the funding or resources to do so. They also questioned whether the survey results would lead to a change in salaries, given the State’s budgetary constraints. According to DSH staff, when DSH last completed a comprehensive salary survey as part of its supplemental report to the Legislature in fiscal year 2014–15, it did not necessarily result in any salary changes. In contrast, staff at CDCR stated that they purchase annual salary surveys from third‑party entities that the department then uses to develop a salary analysis that compares the salaries earned in the public and private sectors. The last salary analysis that CDCR conducted was in December 2023. CDCR staff use the salary surveys to support their requests to CalHR for salary changes for their staff and explained that salary surveys helped them to support compensation requests for staff at Salinas Valley.

Conducting a salary survey could help Atascadero, Porterville, and their respective departments better understand where they perform well and where they perform poorly in the marketplace for health care professionals, including in comparison to staffing agencies. Further, all three departments have funds from unspent salaries for health care staff that they could use to conduct such surveys. The surveys could also provide budget decision‑makers, including the Legislature and CalHR, with information that is critical to ensuring that the State remains competitive as a potential employer for these essential workers.

Although the Three Facilities Have Made Reasonable Recruiting Efforts, They Can Do More to Assess the Effectiveness of Their Strategies

The three facilities we reviewed have made reasonable efforts to recruit new health care professionals, including placing advertisements in various locations, attending career fairs, and hosting hiring events. However, the facilities and their respective departments have not comprehensively evaluated the effectiveness of these efforts to determine where they should focus resources more effectively. A collaborative, state‑led effort to increase recruitment of health care professionals to California could benefit the facilities and help address the State’s decades‑long history of struggling to fill medical and mental health care positions.

Recruiting Efforts

All three facilities have made significant efforts to recruit medical and mental health care professionals through online job advertisements and in‑person or virtual recruiting events. Each of the facilities advertises in social media, radio, industry magazines, and CalCareers, among other locations. We could not determine the exact number of job postings for each facility on the CalCareers website because many postings are ongoing and some are for multiple positions and facility locations. However, Atascadero had at least 4,063 postings during our audit period, while Porterville and Salinas Valley had at least 654 and 974 postings, respectively. Additionally, each of the three facilities participated in numerous recruiting events most years, as Table 4 shows.

Although the three departments and facilities tracked some of their recruiting efforts during our audit period, they could not demonstrate that they actively compared recruiting strategies to determine which are most effective for getting qualified applicants to apply and ultimately get hired. DSH and CDCR stated that they are both in the process of piloting and implementing systems to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of their various recruiting strategies.3 However, these systems are not yet complete enough to generate meaningful data to guide their efforts. As a result, none of the facilities or departments were able to demonstrate which recruiting strategies were most effective in generating the greatest number of applicants and the greatest hiring percentage. We expected that given the number of vacant positions that the facilities need to fill, the departments and facilities would have already evaluated the effectiveness of their recruiting activities; without this information, they cannot leverage their efforts and focus on those that generate the best results.

Appendix E identifies the number of job applications each of the three facilities received and the number of applicants it interviewed and hired for five different job classifications from calendar years 2019 to 2024.

Recruiting Opportunities

When reviewing the three facilities’ recruiting efforts, we identified several potentially effective strategies that some of the facilities have yet to adopt. For example, of the 49 in‑person or virtual recruiting events that Salinas Valley conducted from 2019 through 2024, 25 were one‑ to three‑day hiring events where interested candidates could apply, interview, and receive a contingent job offer before the event concluded. In 2021, CDCR’s deputy director of human resources developed and implemented these hiring events after identifying a need to streamline the state civil service hiring process. The fact that such condensed events shorten and streamline the hiring process suggests that other facilities should consider implementing something similar.

When we asked human resources staff at Atascadero and Porterville about streamlined hiring events, staff at Porterville stated that they prefer the traditional merit‑based hiring process because they can better ensure that candidates meet the facility’s needs. In contrast, DSH’s recruitment unit manager stated that it has successfully run a similar event for some facility support positions. He explained that DSH is open to expanding streamlined recruiting events to recruit for certain medical and mental health care positions. When we evaluated 37 websites from the staffing agencies with which the three facilities contract, we found that many promote a streamlined hiring process.

The staffing agencies also offer flexible work schedules, referral programs, and résumé assistance, along with the ability to work in various locations. Although the three facilities we reviewed cannot offer the last of these benefits, they could consider whether providing additional flexibility in scheduled shifts is feasible. Several of the state employees we interviewed stated that their current shifts do not allow for work‑life balance. Further, a bargaining unit chapter president for employees at Porterville explained that the bargaining unit has attempted to negotiate such flexibility in the past.

Atascadero offers flexible schedules for some of its level of care staff, such as physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, and registered nurses. However, Atascadero offers only limited flexible shifts to the positions in its nursing group, which comprises 77 percent of its medical and mental health care staffing. According to staff, Atascadero previously tried to offer 12-hour shifts to state employees in collaboration with bargaining units, but was unsuccessful in finding enough interested employees to accept the schedule. Staff stated that they also found it difficult to make more 12-hour shift options work with operational needs. We recognize that implementing flexible schedules might be difficult; however other 24‑hour facilities in the private sector, such as hospitals, are successful at implementing a variety of flexible schedules. Both CDCR and DDS were also open to the idea of providing additional flexibility. Although we recognize that the departments would need to negotiate with the bargaining units and adhere to all state requirements before making any changes to staff schedules, the departments and facilities could conduct a study to determine whether doing so would be feasible and whether it would improve employee retention and increase the effectiveness of recruitment efforts.

Atascadero and Porterville could also better leverage their existing assets as part of their recruiting efforts. Both facilities have housing available at their locations that they have at times offered to newly hired employees as a recruiting strategy. Porterville has 30 rental properties, and staff stated that there are normally some vacancies. Atascadero has 17 rental properties and eight single rooms for rent, but staff advised that the units are normally full and the leases are for a limited duration. Staff at Atascadero told us that because the housing is normally full, it is of limited value as a recruiting tool. They believe that obtaining or developing additional housing units would require action by the Legislature. However, neither Atascadero nor DSH has explored this option to attract more candidates for the facility.

The State Could Assist the Facilities’ Recruiting Efforts

The problems related to filling medical and mental health positions are not limited to the three facilities we reviewed. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services projects a national shortage of more than 187,000 full‑time equivalent physicians and a shortage of 208,000 nurses by 2037. In addition, HRSA projects substantial shortages of mental health providers, including psychologists and psychiatrists. Such nationwide shortages suggest that without significant change, filling medical and mental health care vacancies will likely continue to challenge the State.

Although the departments and facilities can and should implement certain recruitment strategies on their own, we believe that the State could achieve greater efficiency and effectiveness by overhauling and centralizing its efforts to recruit medical and mental health care workers. CalHR could collaborate with various departments to improve the recruitment and hiring of medical and mental health care professionals, similar to the Work for California Hiring and Recruiting Campaign it piloted when seeking employees from the technology sector. This three‑month pilot in 2023 included collaboration between 23 state agencies to increase applications for state jobs, reduce high vacancy rates, and decrease application‑to‑hire time frames. The campaign included dozens of promotional videos, coordinated social media posts, and online interest forms, and it resulted in more than 5.4 million interactions and nearly 8,500 interest forms submitted. The project summary noted there were 1,584 hires, a decrease in vacancy rates, and a reduction in application‑to‑hire time frames for some departments.

The State could adopt a similar but broader campaign through which it centralizes recruiting activities in a cross‑collaboration of agencies and facilities to attract and hire more medical and mental health care professionals. Although the technology pilot project ran for only three months, the severity of nationwide health care shortages and the State’s decades‑long history of struggling to fill medical and mental health care positions suggests that the State should consider conducting an ongoing campaign in this instance. The campaign could continue until the State can achieve and maintain minimal vacancy rates in its medical and mental health care classifications.

We spoke with CalHR’s director about conducting a collaborative cross‑agency recruiting campaign to hire more medical and mental health care professionals into state employment, and she was supportive of CalHR facilitating such an effort. She explained that our proposal for CalHR to incorporate online and in‑person assistance to candidates during the application process, and for it to develop and streamline targeted recruitment activities for difficult to recruit classifications and locations, align with her goals to broaden the support that CalHR offers departments. The director stated that CalHR would need additional resources to facilitate such a campaign. However, she acknowledged that by centralizing some recruiting efforts, the State could improve the efficiency of its hiring activities by reducing some duplicative efforts and competition among the various departments.

As we indicate previously, the extent to which the State’s salaries for medical and mental health care positions reflect the current marketplace is unclear. According to CalHR’s deputy director of fiscal and data management, CalHR performs total compensation analyses on some state occupations. However, these analyses are high‑level and do not include all medical and mental health care classifications. He further explained that it is departments’ responsibility to conduct salary studies for specific classifications, which also consider their facilities’ specific geographical locations and competition. He stated that CalHR offers departments guidance on conducting salary studies so that they can appropriately address compensation concerns and obtain the documentation necessary to seek compensation modifications. Therefore, before engaging in a large recruiting campaign, it would benefit the State to facilitate total compensation analyses of all medical and mental health care positions to ensure that compensation is commensurate and competitive with the private sector. Such an effort could also help ensure that state agencies and facilities are not competing with each other to the State’s overall detriment.

Although CalHR would likely be the most appropriate agency to facilitate, manage, and track the results of such a recruitment campaign, CDCR, DDS, and DSH should collaborate with CalHR to pilot and identify the most effective recruitment strategies. Further, the departments should be responsible for vetting, hiring, and onboarding new applicants.

To Address Their Vacancies, the Three Facilities Have Increased Their Use of Contract Workers

Key Points

- Contract health care workers made up between just 4 and 10 percent of overall staffing levels at each facility. However, each facility has increased its use of contract workers in recent years to help address ongoing vacancies.

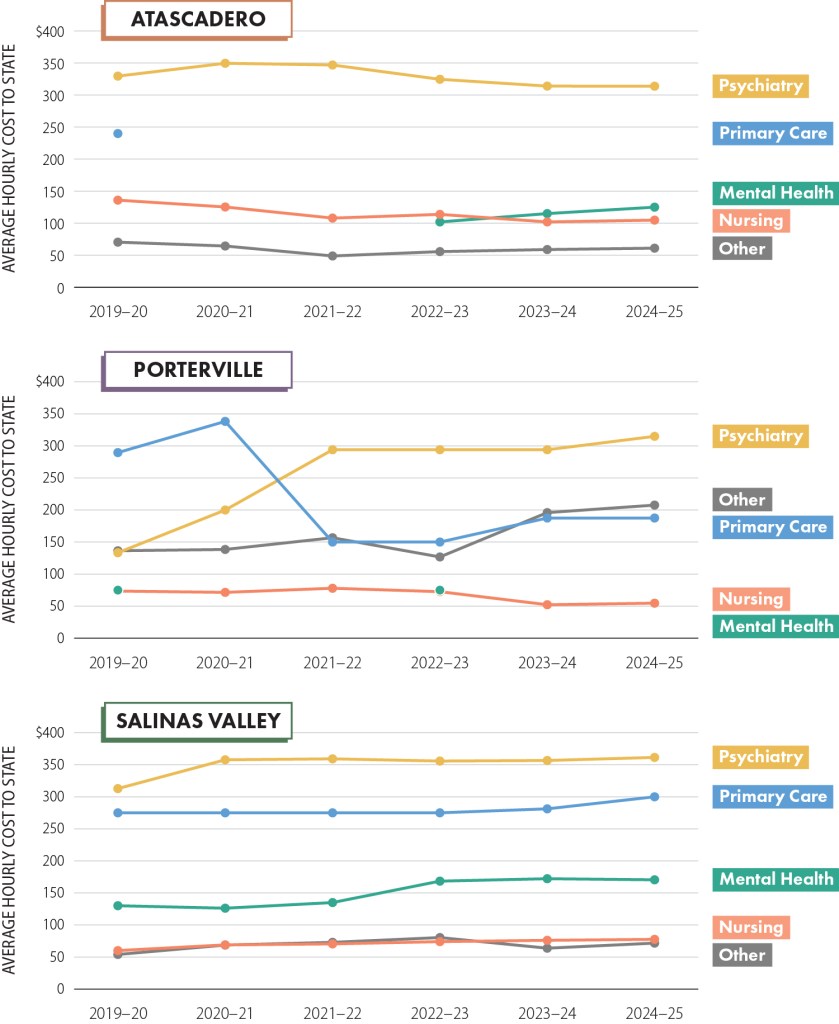

- All three state facilities typically incur higher hourly costs for contract workers than for state employees within the same job classifications, even after accounting for the costs of the benefits state employees receive.

- The contract workers at the three facilities possessed the necessary credentials to work within their classifications. However, they generally had an average of two to three years less tenure than state employees in the same job classifications, thus requiring the State to spend additional time and resources for training.

The Facilities Are Increasingly Using Contract Workers to Provide Health Care

The three facilities we reviewed overwhelmingly rely on state employees rather than contract workers to provide care. However, as they have struggled to fill vacant positions in recent years, they have increasingly needed to rely on contract workers to ensure adequate staffing. Hourly costs for contract workers are generally higher than for state employees in the same job classifications, although costs for some job classifications at Atascadero and Porterville have decreased recently. All three facilities have processes in place to ensure that contract workers have the licenses and qualifications necessary for their positions, but because the contract workers’ tenure at facilities tends to be shorter, they may have less familiarity with the needs of the population for whom they care.

The Facilities’ Use of Contract Workers

Contract workers made up a small share of overall staffing levels at each facility in fiscal year 2023–24, as Table 5 shows. For example, at Atascadero, contract workers accounted for 77 of the facility’s 1,513 authorized positions, or 5 percent; at Porterville, they accounted for 30 of the facility’s 763 authorized positions, or 4 percent; and at Salinas Valley, they accounted for 62 of the facility’s 637 authorized positions, or 10 percent.

Nevertheless, the number of hours worked by contract workers at each facility has increased dramatically over the years, as Figure 6 shows. We estimate that Porterville’s use of contract workers more than doubled from fiscal years 2019–20 to 2024–25, while Atascadero’s and Salinas Valley’s use of contract workers increased by 79 percent and 46 percent, respectively, during the same period.4 The majority of the contracted hours at each facility were in nursing classifications, as the figure illustrates. Specifically, the hours that contract workers covered in nursing classifications during fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25 constituted 87 percent of contract workers’ hours at Porterville, 60 percent of contract workers’ hours at Salinas Valley, and 57 percent of contract workers’ hours at Atascadero. After nursing classifications, the classifications in which contract workers covered the most hours varied by facility.

Figure 6

The Facilities’ Use of Contract Workers Has Increased Dramatically

Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2024–25

Source: Facilities’ contractor invoice data.

Note: Hours worked for fiscal year 2024–25 are projected based on data from July through December 2024.

* Salinas Valley hours worked do not include contract dental providers. Refer to further discussion in the Scope and Methodology in Appendix F.

Stacked column charts for the three facilities from 2019 to 2020 through 2024 to 2025 showing the increase in hours worked by contract staff by 79 percent at Atascadero, 172 percent at Porterville, and 46 percent at Salinas Valley overall across the groupings of Nursing, Mental Health, Psychiatry, Primary Care, and Other. Amounts are in the thousands of hours.

At Atascadero, in 2019 to 2020, contract staff worked over 31000 hours in the Nursing grouping, about 42000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, just over 900 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and just over 6000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2020 to 2021, contract staff worked nearly 25000 hours in the Nursing grouping, about 45000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, 0 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and just over 5200 hours in the Other grouping. In 2021 to 2022, contract staff worked just over 67000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 43000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, and nearly 4000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2022 to 2023, contract staff worked nearly 103000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 1500 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 43000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, and nearly 17000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2023 to 2024, contract staff worked just over 105000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 1000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, nearly 38000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, and over 17000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2024 to 2025, contract staff worked just over 9000 hours in the Nursing grouping, just over 1000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, nearly 38000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, 0 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and nearly 16000 hours in the Other grouping.

At Porterville, in 2019 to 2020, contract staff worked nearly 21000 hours in the Nursing grouping, 40 hours in the Mental Health grouping, nearly 40 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 800 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 8000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2020 to 2021 contract staff worked over 34000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 16 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, nearly 1700 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and nearly 8800 hours in the Other grouping. In 2021 to 2022 contract staff worked just over 32000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 80 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, 60 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 5300 hours in the Other grouping. In 2022 to 2023 contract staff worked over 53000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 110 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 170 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, nearly 70 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 6700 hours in the Other grouping. In 2023 to 2024 contract staff worked nearly 59000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 200 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, nearly 70 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 5000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2024 to 2025 contract staff worked nearly 75000 hours in the Nursing grouping, 190 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 60 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 4500 hours in the Other grouping.

At Salinas Valley, in 2019 to 2020, contract staff worked over 46000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 27000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 3700 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 1400 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and nearly 13000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2020 to 2021 contract staff worked over 63000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 29000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 5700 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, nearly 4800 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 10400 hours in the Other grouping. In 2021 to 2022 contract staff worked over 64000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 24000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 7000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 5500 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 7000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2022 to 2023 contract staff worked nearly 78000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 22000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, nearly 7000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 6200 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and over 7200 hours in the Other grouping. In 2023 to 2024 contract staff worked over 84000 hours in the Nursing grouping, over 24000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, over 7100 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, nearly 2000 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and nearly 12000 hours in the Other grouping. In 2024 to 2025 contract staff worked nearly 83000 hours in the Nursing grouping, nearly 30000 hours in the Mental Health grouping, nearly 7000 hours in the Psychiatry grouping, over 2800 hours in the Primary Care grouping, and nearly 12000 hours in the Other grouping.

According to facility staff, the facilities increased their use of contract workers in part to fill their ongoing vacant positions. They explained that the facilities use contract workers to cover shifts when state employees are not available and that they increased their use of contract workers in part because they did not have enough state employees to work needed shifts. Staff also attributed the increase to the COVID‑19 pandemic, when each facility had to address pandemic‑related needs. For example, staff at Salinas Valley and Atascadero stated that they had to rely on contract staff to test patients for COVID‑19, treat patients who tested positive for the virus, and replace state employees who tested positive for COVID‑19 and had to isolate themselves. In addition, staff at Atascadero stated that a reduction in the number of mandatory overtime shifts and an increase in state employees being out on medical leave also led the facility to increase its use of contract workers.

The Number and Value of Health Care Contracts

As part of our review, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) asked us to determine the number and cost of each facility’s medical and mental health care staffing contracts. Each of the three facilities we audited takes a different approach to contracting for health care workers. Atascadero uses contracts that DSH enters into on the facility’s behalf, as well as contracts that the facility itself enters.5 Porterville executes its own staffing contracts with both staffing agencies and individual providers. CDCR maintains staffing contracts for Salinas Valley and other correctional facilities. It has had one contract in place for medical staffing since 2014 and a second contract with the same vendor since 2017—updated in 2022—for dental and mental health care staffing. We list the three facilities’ contracts in Appendix A.

The annual maximum value of the three facilities’ health care contracts increased by nearly two times to more than five times from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25, although the facilities spent only a portion of the maximum contract values.6 Of the three facilities, Atascadero had the largest increase in the value of its contracts, from $65 million in fiscal year 2019–20 to $213 million in fiscal year 2024–25, as Figure 7 shows. The number of Atascadero’s contracts also more than doubled from 13 contracts to 28 contracts during this period.

Figure 7

The Projected Value of the Facilities’ Health Care Staffing Contracts and the Amounts the Facilities Spent on Contract Workers Have Generally Increased

Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2024–25

Source: Staffing contracts, contractor invoice data, and budget documents.

Note: Amount spent for fiscal year 2024–25 is projected based on data from July through December 2024. Salinas Valley contract amounts do not include contract dental providers. Refer to further discussion in the Scope and Methodology in Appendix F.

Stacked bar chart showing that from fiscal years 2019 to 2020 through 2024 to 2025, total projected value of health care staffing contracts increased at all three facilities, though total amount spent on these contracts was generally less than half of the total value of the contracts.

A callout box explains that each bar shows the projected value of the facility’s health care staffing contracts and the actual amount the facility spent on contract workers for that fiscal year.

During this time period, the total number of available contracts at Atascadero was 46, with a total projected contract value of 853112582 dollars. The total contract amount spent was 131719370 million dollars, 15 percent of the total maximum projected value. In fiscal year 2019 to 2020, the projected contract value was 65 million dollars, and the amount spent was 19 million dollars. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the projected contract value was 141 million dollars, and the amount spent was 19 million dollars. In fiscal year 2021 to 2022, the projected contract value was 147 million dollars, and the amount spent was 18 million dollars. In fiscal year 2022 to 2023, the projected contract value was 84 million dollars, and the amount spent was 28 million dollars. In fiscal year 2023 to 2024, the projected contract value was 203 million dollars, and the amount spent was 25 million dollars. In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the projected contract value was 213 million dollars, and the amount spent was 22 million dollars.

During this time period, the total number of available contracts at Porterville was 101, with a total projected contract value of 60071699 dollars. 24146425 million dollars were spent on these contracts, 40 percent of the total projected value. In fiscal year 2019 to 2020, the projected contract value was 3 million dollars, and the amount spent was 3 million dollars. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the projected contract value was 14 million dollars, and the amount spent was 5 million dollars. In fiscal year 2021 to 2022, the projected contract value was 6 million dollars, and the amount spent was 3 million dollars. In fiscal year 2022 to 2023, the projected contract value was 5 million dollars, and the amount spent was 5 million dollars. In fiscal year 2023 to 2024, the projected contract value was 13 million dollars, and the amount spent was 4 million dollars. In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the projected contract value was 18 million dollars, and the amount spent was 5 million dollars.

During this time period, the total number of available contracts at Salinas Valley was 3, with a total projected contract value of 154338940 dollars. 82697370 million dollars were spent on these contracts, 54 percent of the total projected value. In fiscal year 2019 to 2020, the projected contract value was 18 million dollars, and the amount spent was 9 million dollars. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the projected contract value was 25 million dollars, and the amount spent was 13 million dollars. In fiscal year 2021 to 2022, the projected contract value was 31 million dollars, and the amount spent was 13 million dollars. In fiscal year 2022 to 2023, the projected contract value was 17 million dollars, and the amount spent was 15 million dollars. In fiscal year 2023 to 2024, the projected contract value was 31 million dollars, and the amount spent was 16 million dollars. In fiscal year 2024 to 2025, the projected contract value was 32 million dollars, and the amount spent was 17 million dollars.

According to DSH’s former business management branch chief, the department projects contract values based on staffing needs in anticipation of a worst‑case scenario, such as another pandemic. She explained that the department now typically enters into contracts with multiple vendors for the same services to ensure that contract workers will be available when needed. She also stated that although the value of the contracts has increased, the facility pays for only the services it uses and does not spend or encumber the full value of the contracts. Further, Atascadero modified its contracting practices in 2023 to enter into contracts directly with vendors rather than using interagency agreements, increasing the number of its staffing contracts.

Although the number of Porterville’s health care staffing contracts remained fairly consistent from fiscal years 2019–20 to 2024–25, the annual value of those contracts increased five‑fold, from $3.5 million to $18 million. Porterville had a total of 101 staffing contracts with a total value of $60 million during this time. Porterville’s staff explained that before the pandemic, it used personal service contracts only for medical specialty services, such as neurology, cardiology, and ophthalmology. They stated that the facility now contracts with multiple vendors that provide contract workers in various health care job classifications and that its contracts with those vendors are larger than the specialty contracts it used in previous years.

Finally, the annual value of contracts that CDCR allotted to Salinas Valley almost doubled from $18.4 million in fiscal year 2019–20 to $32 million in fiscal year 2024–25. In each year during our review period, CDCR had one contract for medical staffing and another for dental and mental health care staffing, both with the same vendor. CDCR is able to maintain fewer contracts than the other facilities because its contracts are network contracts, in which the vendor subcontracts with other staffing agencies to provide contract workers. CDCR staff explained that increases in costs led to an increase in its contract values.

The Facilities’ Spending on Contract Workers

Although the three facilities did not spend all funds allocated to their staffing contracts during the years we reviewed, the annual amount each facility spent on contract workers has increased since fiscal year 2019–20. As Figure 8 shows, from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25, we estimate that annual spending on contract staff increased by $3.3 million at Atascadero, by $1.7 million at Porterville, and by $7.6 million at Salinas Valley.

Figure 8

The Amount Each Facility Spent on Contract Workers Has Generally Increased

Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2024–25

Source: Facilities’ contractor invoice data.

Notes: Spending for fiscal year 2024–25 is projected based on data from July through December 2024.