2024-111 California Colleges

California’s Systems of Public Higher Education Could Better Address Student Housing Needs

Published: October 14, 2025Report Number: 2024-111

October 14, 2025

2024-111

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, CA 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the State’s three systems of public higher education—the University of California (UC), the California State University (CSU), and California Community Colleges (CCC)—and each system’s efforts to provide affordable student housing. In general, we determined that despite the State’s efforts to address student housing needs, the UC Office of the President, CSU Office of the Chancellor, and CCC Chancellor’s Office have not assumed strategic leadership roles in planning for affordable student housing throughout their respective systems.

For example, the system offices do not direct or conduct any centralized planning efforts to increase the availability of student housing, relying instead on their individual campuses to conduct such planning. The system offices compile and submit to the Legislature annual capital outlay plans that are informed by their respective campuses and do not specify how proposed housing projects would contribute to accommodating the needs of students. We recommend that the Legislature clarify in state law its intent that system offices should assume stronger oversight in planning campus housing, which should include requiring the systems to conduct a regular assessment of unmet demand for campus housing at each of their respective campuses. In doing so, the systems could better ensure that their campuses are working toward making college more affordable while helping more students access higher education by best serving their housing needs.

The State established the Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program in 2021 with the goal of providing affordable, low-cost housing options for students enrolled at UC, CSU, and CCC campuses. However, these projects may not remain affordable after construction because of insufficient monitoring requirements. We also found that the UC, CSU, and CCC campuses we reviewed did not always provide accurate information on their websites about the cost of attendance or the availability of housing assistance programs. To address this issue, the systems should regularly monitor their respective campuses’ websites for compliance with applicable laws.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CBO | Community-based organizations |

| CCC | California Community Colleges |

| CSU | California State University |

| HUD | U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| SEARS | Student Expenses and Resources Survey |

| Student Aid | California Student Aid Commission |

| UC | University of California |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

More than 2 million students are enrolled through California’s three systems of public higher education—the University of California (UC), the California State University (CSU), and the California Community Colleges (CCC). Students have the options of living in campus-operated student housing facilities (campus housing) or living off campus, which can include living alone, or with parents, relatives, or housemates. Research conducted by CSU Northridge, the University of Oregon, and the University of Connecticut found that students who live in campus housing have better outcomes, such as higher grade point averages (GPAs) and graduation rates, than students who live off campus. Nevertheless, campuses are able to accommodate only a proportion of their student population who seeks campus housing. To address high construction and land costs for campus housing and to facilitate access to higher education for students with low incomes, the State established the Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program (Grant Program) in 2021 to provide affordable, low-cost housing options for students enrolled at the three systems.

The State’s Public Higher Education Systems Do Not Have Sufficient Processes to Identify Student Housing Needs

California’s housing shortage affects students at all three of its public higher education systems. Although the State has generally regarded meeting student housing needs as the responsibility of individual campuses, the UC Office of the President, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the CCC Chancellor’s Office are requested or directed to undertake oversight roles in gathering information, allocating funds, and administering Grant Program applications to address student housing needs. However, the three system offices have not assumed a strategic leadership role in planning for housing across their respective systems. For example, none of the systems has fully assessed its unmet demand for student housing; instead the systems have relied on incomplete measures such as housing waitlists that may understate that demand. Further, the three systems have engaged in only minimal system-level planning to help identify efficient housing projects that could serve more than one campus. Finally, the CSU Office of the Chancellor based its required plan for meeting its projected student housing needs on limited and outdated market demand studies. This plan also omitted potential market demand for new beds at 12 campuses that did not report market demand or waitlist data, potentially understating unmet demand for campus housing.

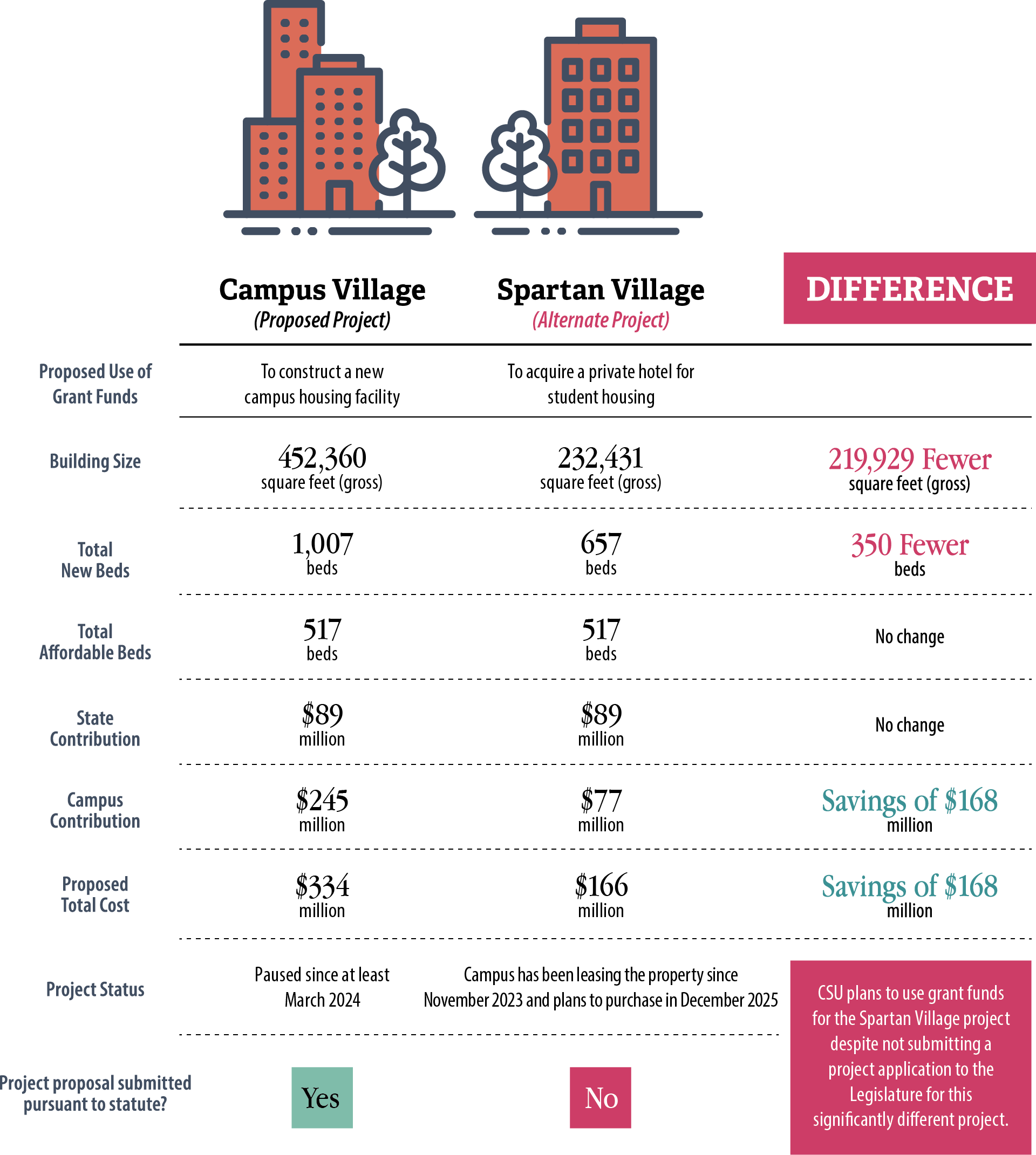

Changes to the Grant Program and Limited Monitoring Threaten Campuses’ Ability to Offer Students Low-Income Housing

The Legislature established the Grant Program to provide funding opportunities for UC, CSU, and CCC campuses to construct or acquire housing projects that would provide low-cost housing options for students. However, changes made to the funding structure of the Grant Program have impeded progress on some projects. For example, four authorized Grant Program projects at CCC campuses have not received any state funding and have not started construction, delaying the availability of nearly 1,700 new affordable beds at those campuses. Although the UC Office of the President and the CSU Office of the Chancellor could not provide us with a current update on each of their projects, all three systems have established processes to regularly monitor and report on those projects during construction, as state law requires. Nevertheless, the Legislature and the three systems should take steps to ensure that monitoring activities continue for the life of the housing projects that receive funding from the Grant Program so that these projects continue to provide affordable housing for future students. Finally, CSU plans to use Grant Program funding on a project at San José State University that CSU did not submit through the statutory application process and that the Legislature appropriated for a different project at that campus.

Students and Their Families May Have Difficulty Understanding Education Costs and the Availability of Housing Assistance

The housing information that campuses post online is not always accurate or reliable. For example, three campuses we reviewed did not separately list the cost of campus housing and the cost of meal plans as state law requires. Further, campuses are not always transparent about how they calculate their cost estimates: none of the websites for the CSU campuses we reviewed included a description of the data sources and methods they used to calculate cost-of-attendance estimates, as state law requires. Finally, eight of the nine campuses that we reviewed did not post on their websites housing assistance information, such as eligibility requirements and application instructions for their housing assistance programs. As a result, students in need may not be aware of the services their campus provides.

To address these findings, we recommended that the Legislature should consider clarifying in statute a stronger leadership role for the system offices related to planning campus housing and requiring them to regularly assess their campuses’ unmet demand for housing. We also recommended that the Legislature should establish a working group composed of representatives from each of the three systems to identify opportunities for intersegmental collaboration to build campus housing. Further, we recommended that the three systems should establish policies and processes to ensure that beds or rents remain affordable for the life of each campus Grant Program facility and that they should establish procedures to verify that their campuses’ websites reflect accurate housing information. Lastly, the CSU Office of the Chancellor should refrain from spending Grant Program funding on projects that have not been submitted to or approved by the Legislature.

Agency Comments

The UC Office of the President and the CSU Office of the Chancellor generally concurred with our recommendations. However, the CSU Office of the Chancellor disagreed with the finding that the Spartan Village project at San José State was not authorized. The CCC Chancellor’s Office did not have any comments on the findings or recommendations. Because we did not make recommendations to the nine campuses we reviewed, we did not expect nor did they provide responses.

Introduction

Background

In recent decades, California has experienced a persistent and escalating housing shortage that has contributed to rising housing costs, increased homelessness, and growing barriers to housing access for residents across the State. This shortage has had a particularly severe effect on college students, with recent reports indicating that more than half of surveyed students across all three of the State’s systems of higher education have experienced housing insecurity—lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence—and that 5 percent to 20 percent of college students have faced periods of homelessness. Research from the Center for Postsecondary Success and the National Institutes of Health shows that students who experience housing insecurity are more likely to have lower mean GPAs, poorer physical health, and higher rates of depression and anxiety than their peers.

In response to the State’s housing crisis, the Legislature enacted a number of laws and appropriated targeted funding to expand housing. One of its initiatives is the Grant Program, which focuses specifically on increasing affordable student housing for the purposes of facilitating access to higher education for students with low incomes. The Legislature declared that the shortage of student housing places higher cost pressure on local housing markets, exacerbating the broader housing crisis and creating challenges for communities near college campuses.

Additionally, the Public Policy Institute of California reported that California is facing a degree gap—a shortfall of college graduates compared to the State’s workforce needs. To address such concerns, the Governor established a statewide goal of achieving 70 percent postsecondary degree and certificate attainment among working-aged Californians by 2030. This goal will likely lead to increased enrollment at all three state systems, putting further strain on student housing. Ensuring that housing is both available and affordable for college students is therefore vital to achieving this goal and to advancing the State’s overall housing, economic, and higher education objectives.

California’s Public Higher Education Systems

California’s three systems of public higher education—UC, CSU, and CCC—serve a combined total of more than 2 million students across the State, some of whom live in campus-owned, campus-operated, and campus-affiliated student housing facilities. Each system plays a distinct role in California’s higher education landscape. The UC system, which operates 10 campuses, is the primary state-supported academic agency for research and is the only one of the three systems with the authority to award the doctoral degree in all fields of learning. The CSU system, with 23 campuses, is the nation’s largest system of four-year higher education, and its primary mission is undergraduate and graduate instruction through the master’s degree. The CCC system, comprising 116 campuses, is the largest system of higher education in the country, and its primary mission is to advance California’s economic growth and global competitiveness through education, training, and services that contribute to continuous workforce improvement. The CCC system offers academic and vocational instruction through the second year of college, grants associate degrees, prepares students for transfer to four-year institutions, and may award baccalaureate degrees in certain circumstances.

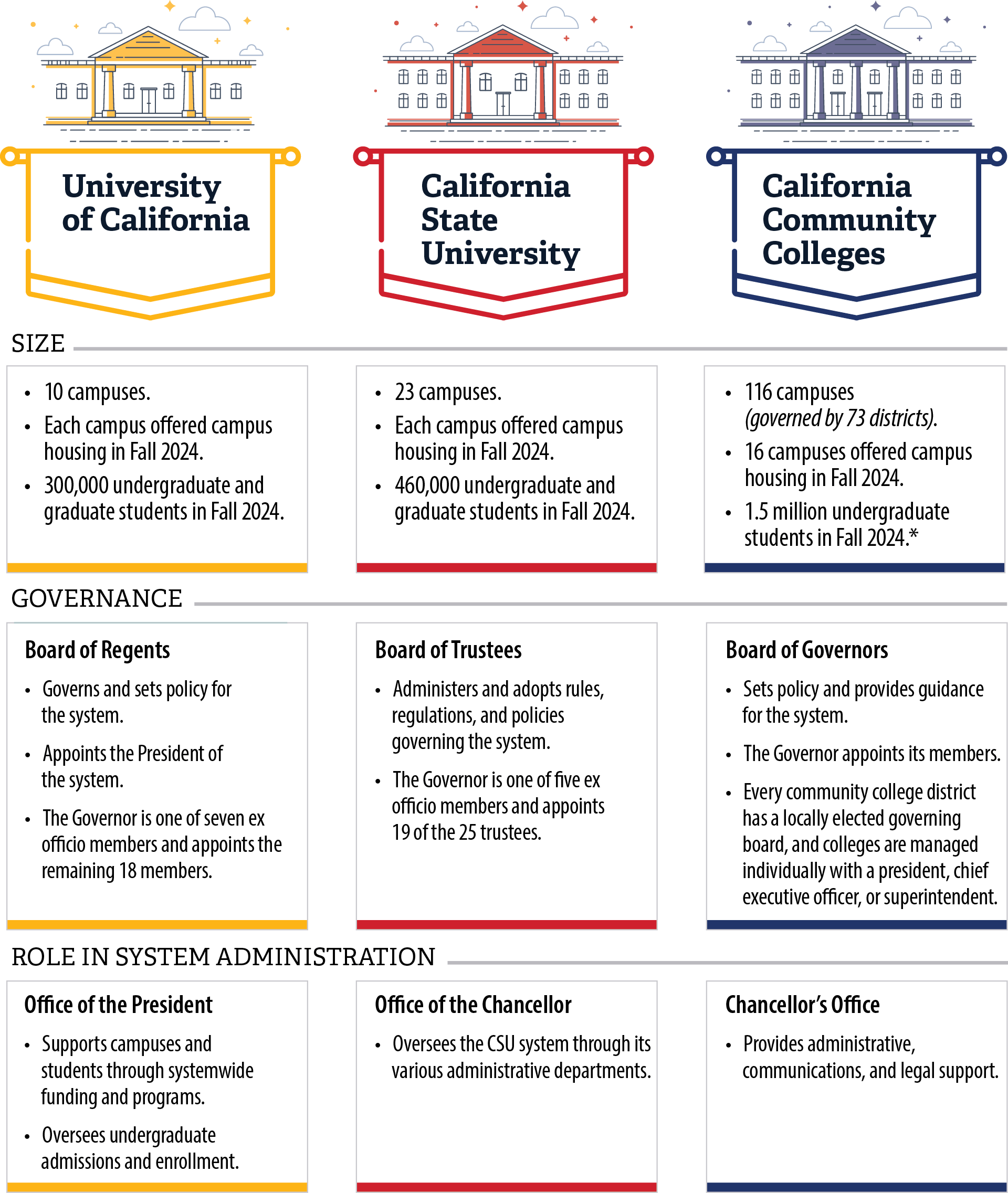

As Figure 1 shows, each system has a governing board that establishes policy and provides guidance for it. Each system also has a central administrative office—the UC Office of the President, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the CCC Chancellor’s Office—that supports its campuses and oversees the system, which includes overseeing capital projects such as campus housing. Under state law, any campus of the UC or CSU system and the governing board of any CCC district may establish and maintain student housing facilities.

Figure 1

California’s Public Higher Education Systems Differ in Size, Governance, and Administrative Oversight

Figure 1 provides a comparison of California’s public higher education systems, focusing on the University of California (UC), California State University (CSU), and California Community Colleges (CCC). The figure highlights key aspects such as size, governance, and administrative oversight. The UC system, governed by the Board of Regents, consists of 10 campuses with 300,000 students. The CSU system, overseen by the Board of Trustees, includes 23 campuses with 460,000 students. The CCC system, managed by the Board of Governors, comprises 116 campuses governed by 73 districts, with 1.5 million students. The figure also notes that each system offers campus housing, with the UC and CSU systems providing housing at all campuses, while only 16 CCC campuses offer housing.

Source: State law, system websites, and system enrollment data.

* The CCC systemwide Fall 2024 enrollment does not include enrollment for Calbright College and Victor Valley Community College because the CCC Chancellor’s Office had not received Fall 2024 data from those colleges as of August 2025.

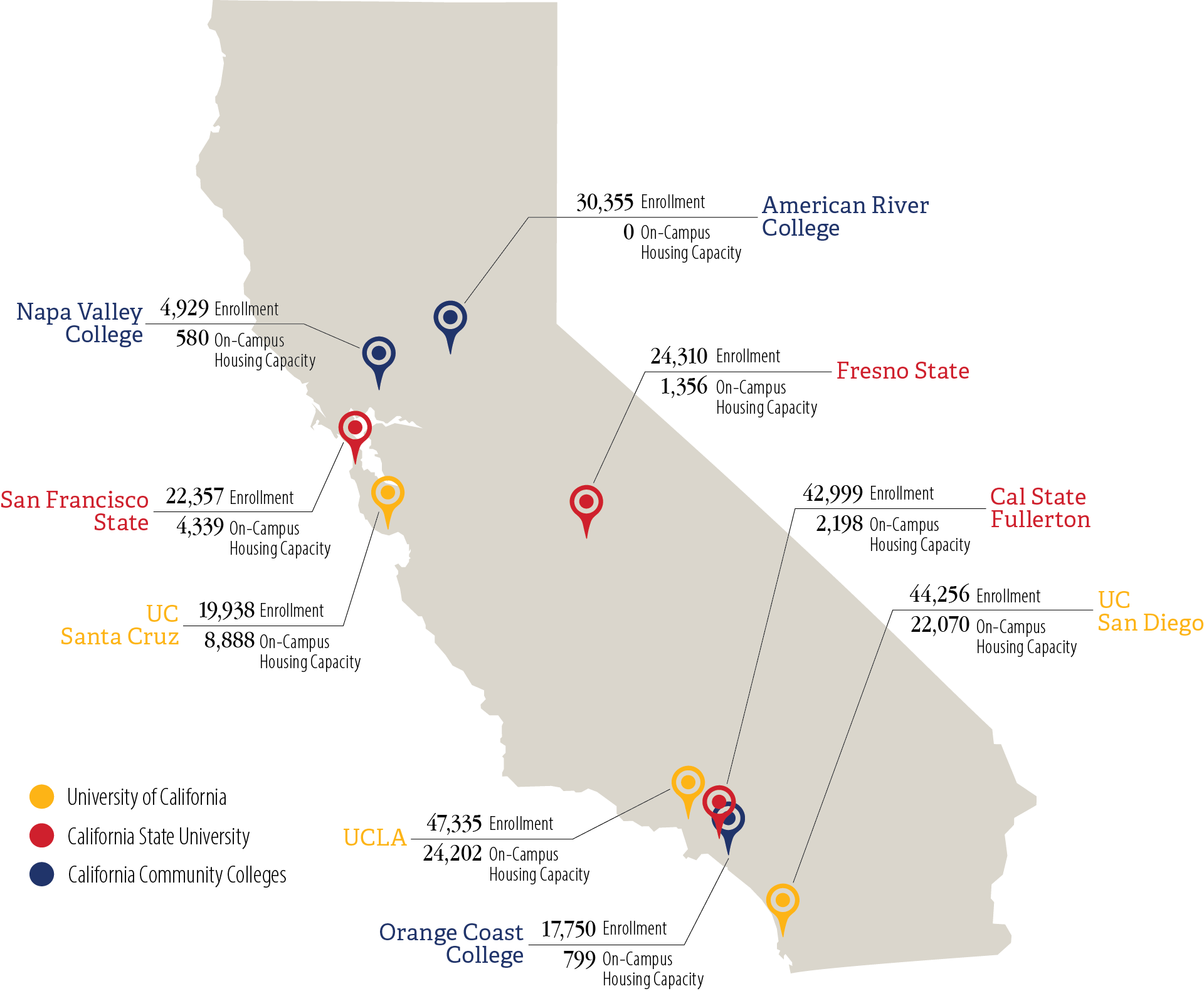

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed us to select a total of nine campuses for review—three campuses from each system. Our selection rationale included, but was not limited to, the campuses’ regional housing costs, enrollment, geography, and housing capacity—which is typically defined as the number of beds available in campus housing. Further, we evaluated whether the campuses received any funding from the State to increase their housing capacity or to address housing insecurity. As Figure 2 shows, we selected UCLA, UC San Diego, and UC Santa Cruz from the UC system; Fresno State, Cal State Fullerton, and San Francisco State from the CSU system; and American River College, Napa Valley College, and Orange Coast College from the CCC system.

Figure 2

We Reviewed Three Campuses From Each of the Systems

Figure 2 is a map showing the enrollment and on-campus housing capacity for three campuses from each of the University of California, California State University, and California Community Colleges campuses that we reviewed. The figure underscores a disparity between student enrollment and available on-campus housing across the three systems.

Source: Analysis of campus enrollment and capacity data from Fall 2024.

Note: We selected American River College—a campus that does not currently offer student housing—to ensure that the audit reflects the full range of campus responses and systemwide planning efforts to address student housing needs.

Campus Housing

Students enrolled at California’s public colleges and universities pursue a variety of living arrangements depending on their financial circumstances, campus location, and individual preferences. Although some students reside in campus housing, others may live alone, with parents, relatives, or housemates, which we refer to throughout this report as residing off campus. Campus housing can have a positive influence on students’ academic experience, financial stability, and overall well‑being. For example, beginning in 2018, the National Survey of Student Engagement conducted a three‑year study that found that first-year and second‑year students who lived in campus housing maintained a higher rate of enrollment than those who lived off campus, including students who lived with their families. Additionally, CSU Northridge reported that first-time college students who entered the university in Fall semesters from 2005 through 2018 and lived in campus housing tended to have higher first-year GPAs, higher third‑term continuation rates, and lower academic probation rates than comparable students who lived off campus. Similar research from the University of Oregon and the University of Connecticut concluded that students who opt to live in campus housing their first year and continue residing there during their second year have higher cumulative GPAs, are more likely to remain in school, and are more likely to graduate than their peers who live off campus.

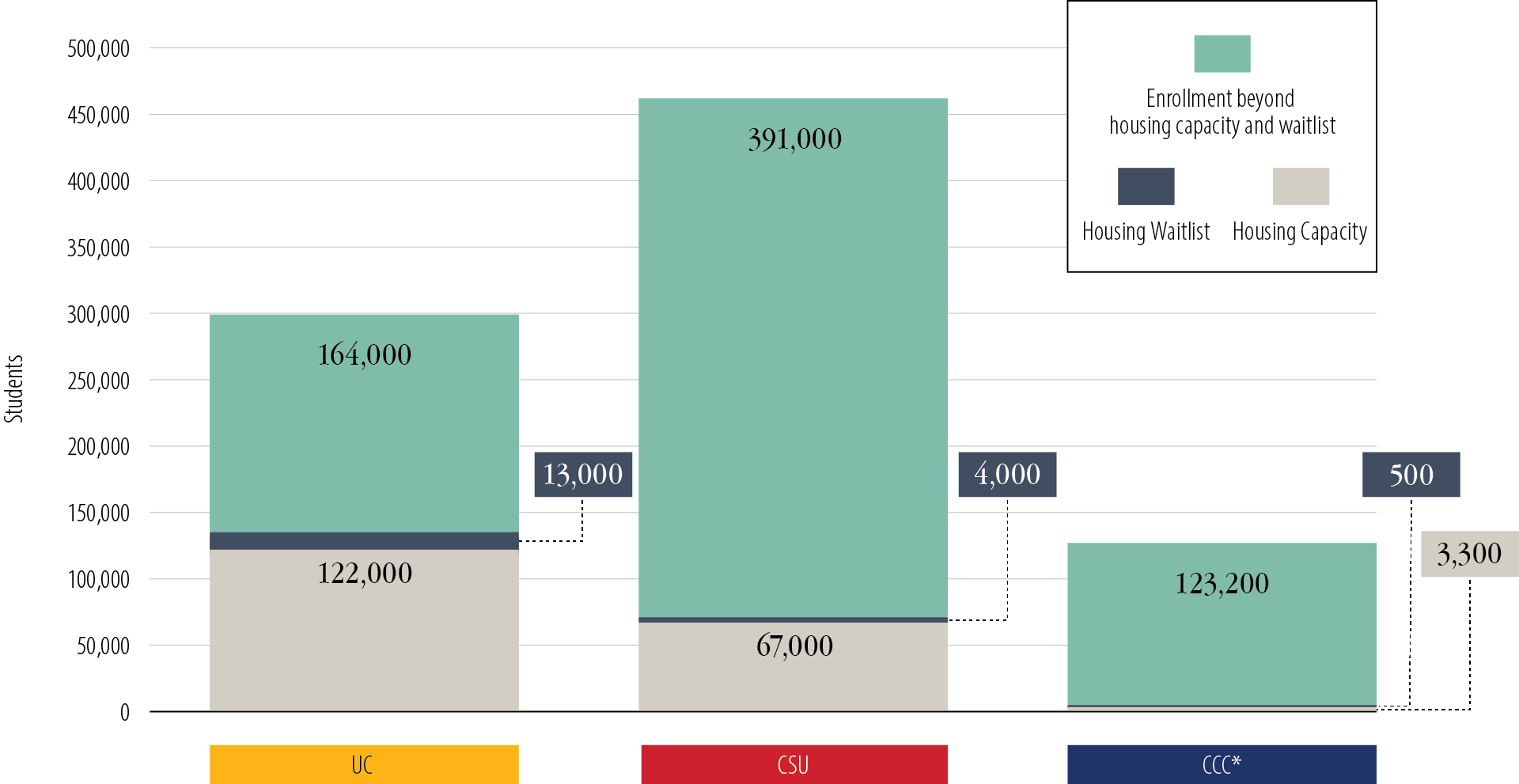

Nonetheless, as Figure 3 shows, student enrollment at the three systems greatly exceeds their campuses’ total housing capacity. In academic year 2024–25, the UC system accommodated about 41 percent of its student population, with more than 122,000 students occupying campus housing across all UC campuses. The proportion of students in campus housing varied among the campuses of the UC system, ranging from a low of 24 percent of enrolled students at UC Berkeley to a high of 51 percent of enrolled students at UCLA. Notably, even at UC—the system with the greatest housing availability—most students live off campus, underscoring the limits of existing capacity.

Figure 3

The Number of Students Enrolled Systemwide Significantly Exceeded the Number of Available Beds in Fall 2024

Figure 3 is a bar chart comparing the housing waitlist, housing capacity, and total enrollment for the University of California, California State University, and California Community Colleges systems in Fall 2024. The figure underscores the unmet demand for campus housing across all three systems, with the UC system having the highest number of students on housing waitlists and the CCC system having the lowest housing capacity.

Source: Systemwide enrollment data and systemwide capacity reports.

The enrollment presented reflects only the 16 CCC campuses that offered campus student housing in academic year 2024–25.

During the same period, the CSU system had the capacity to house about 15 percent of its student population, although housing rates varied significantly by campus. For example, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo housed about 38 percent of its enrolled students, and CSU Bakersfield housed slightly less than 4 percent of enrolled students. Campus housing is particularly limited in the CCC system. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, CCC students are less likely than CSU students and especially UC students to move to new locations to attend school, likely making campus housing a more attractive option for students at the latter two systems. In fact, as of Fall 2024, only 16 of the CCC system’s 115 physical college campuses offered campus housing, accommodating less than 3 percent of the enrolled students at those 16 campuses and less than 1 percent of enrolled students systemwide.

Unmet Demand for Campus Housing

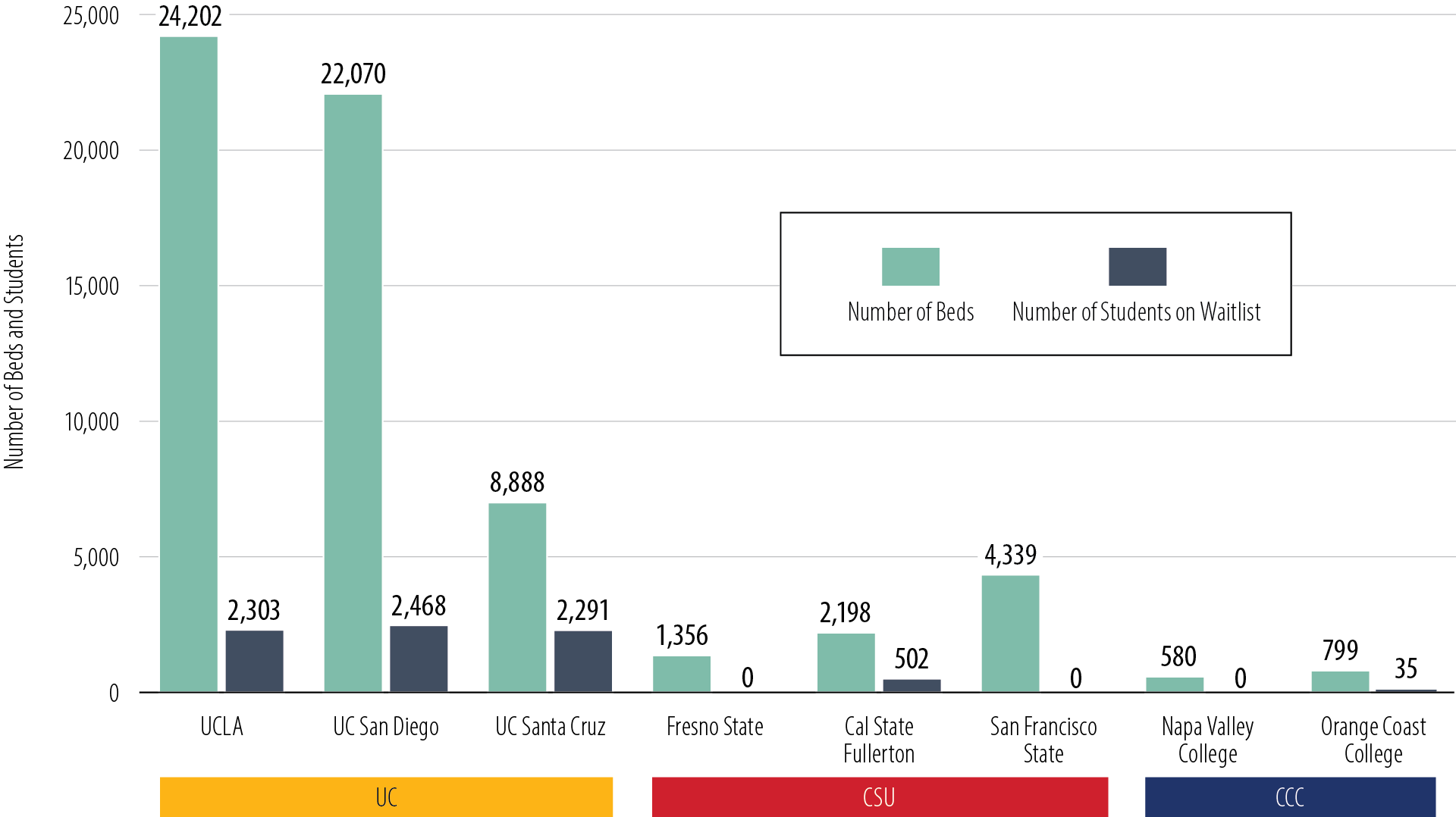

Although not every student seeks campus housing, the absence of housing options or lack of availability at certain campuses results in unmet demand. When more students apply for a campus’s housing program than it can accommodate, the campus will generally establish a student housing waitlist that provides some insight into the demand for campus housing. From Fall 2022 through Fall 2024, all 10 UC campuses reported students on housing waitlists, with a systemwide total of more than 13,000 students on waitlists in Fall 2024. In comparison, only five CSU campuses reported that they had students on waitlists for campus housing in Fall 2024. However, CSU campuses reported their waitlist numbers after instruction had already begun, when those figures would have been at their lowest. For Fall 2024, 12 of the 16 CCC campuses that provide student housing collectively reported a total of 515 students waiting for campus housing. As Figure 4 shows, five of the nine campuses we reviewed across the three systems reported a waitlist for campus housing in Fall 2024.1 These waitlist numbers alone—which do not fully reflect all unmet demand—make clear that students across all three systems would likely benefit from additional housing.

Figure 4

Five Campuses We Reviewed Reported Having Campus Housing Waitlists in Fall 2024

Figure 4 is a bar chart that compares the number of beds to the number of students on housing waitlists in Fall 2024 across five campuses we reviewed. The figure highlights the following data: UCLA had 24,202 beds with 2,303 students on the waitlist, UC San Diego had 22,070 beds with 2,468 students on the waitlist, and UC Santa Cruz had 8,888 beds with 2,291 students on the waitlist. For the CSU campuses, Fresno State had 1,356 beds with no students on the waitlist, Cal State Fullerton had 2,198 beds with 502 students on the waitlist, and San Francisco State had 4,339 beds and no students on the waitlist. For the CCC campuses, Orange Coast College had 799 beds with 35 students on the waitlist, and Napa Valley College had 580 beds with 0 students on the waitlist.

Source: CSU and CCC annual campus housing data reports, UC campus waitlist and housing occupancy reports.

Note: American River College does not offer campus housing.

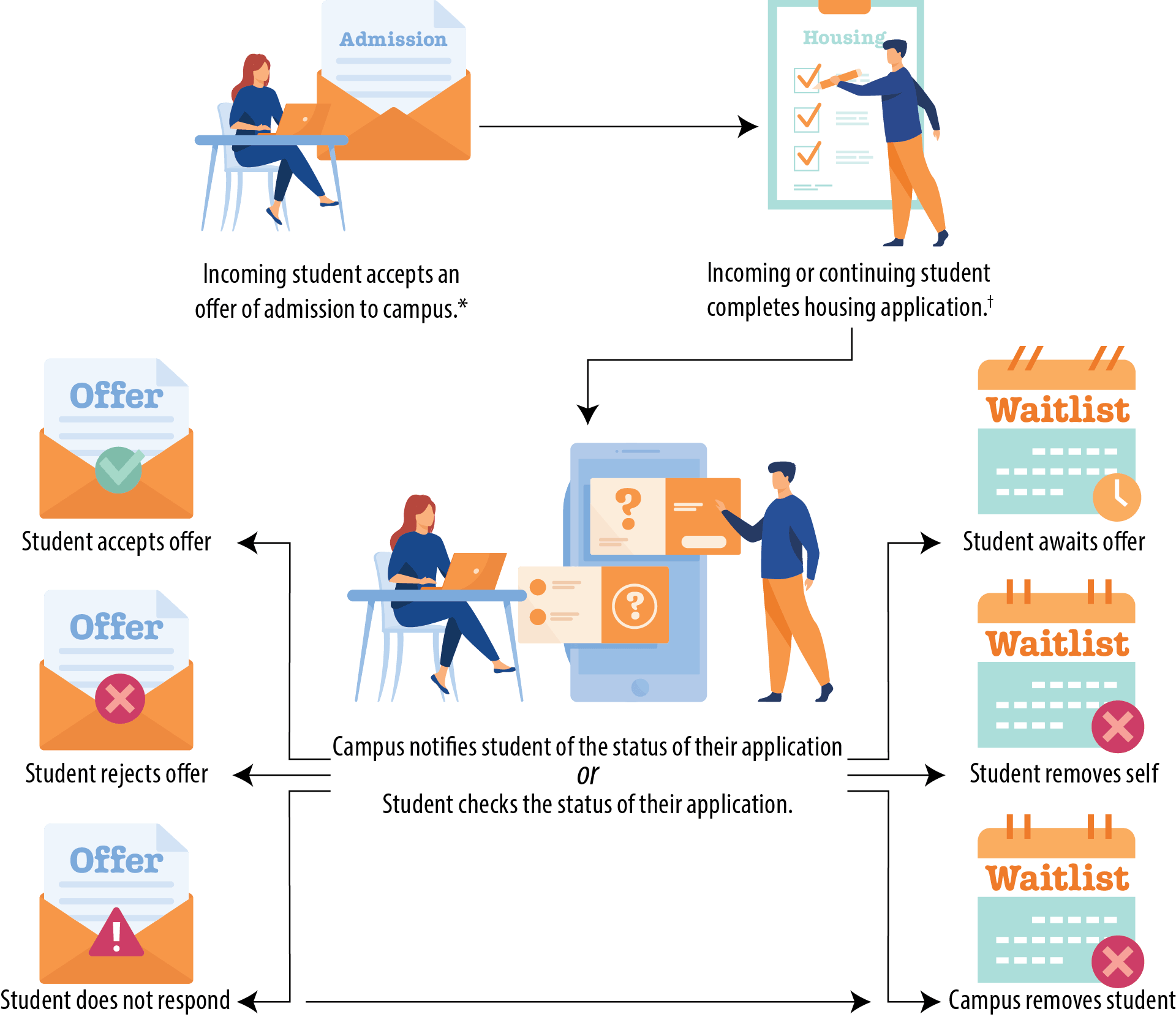

Although each campus designs its own student housing application and assignment process (housing application cycle) to assign applicants to available beds, we observed some general trends that apply to all campuses. For example, a campus’s housing application cycle takes place over the course of several months. As Figure 5 shows, the housing application cycle typically begins with a student’s submission of an application for campus housing and ends with several possible outcomes, including the student’s acceptance of the campus’s offer of housing. If a campus cannot make a housing offer to an applicant, the campus may add that applicant to its housing waitlist.

Figure 5

Campuses Will Create a Campus Housing Waitlist If They Cannot Initially Offer All Applicants a Bed in Campus Housing

Figure 5 provides a flowchart of the housing application process at various campuses, particularly focusing on what happens when campuses cannot initially offer all applicants a bed in campus housing. The process begins with an incoming student accepting an offer of admission to the campus. The student then completes a housing application. The campus notifies the student of the status of their application, or the student checks the status themselves. The student may receive an offer or may be placed on a waitlist. Students who receive an offer may accept it, reject it, or fail to respond. Students on the waitlist may await an offer, remove themselves, or be removed by the campus if they do not respond to an offer.

Source: Campus housing websites and interviews with campus housing officials.

* Campus officials indicated that Orange Coast College maintains a year-round application process, and Napa Valley College allows students to submit a housing application before registering for courses.

† Some campuses—including the three UC campuses we reviewed—offer housing guarantees to incoming undergraduates. To accommodate these students with an offer of housing, campuses will often set aside a predetermined number of beds. Campuses place students with housing guarantees on campus housing waitlists only if the students declined an initial offer or missed a deadline.

The housing application cycles at the campuses of each of the individual systems share other similarities. For example, each of the three UC campuses we reviewed—UCLA, UC San Diego, and UC Santa Cruz—offers a housing guarantee for incoming undergraduates, although the length of this guarantee varies depending on the campus, and students must meet certain conditions, such as adhering to application, contract, and enrollment deadlines. In contrast, two of the CSU campuses we reviewed—Cal State Fullerton and Fresno State—did not offer students a housing guarantee but instead generally used a first-come, first-served approach when assigning students to available beds.

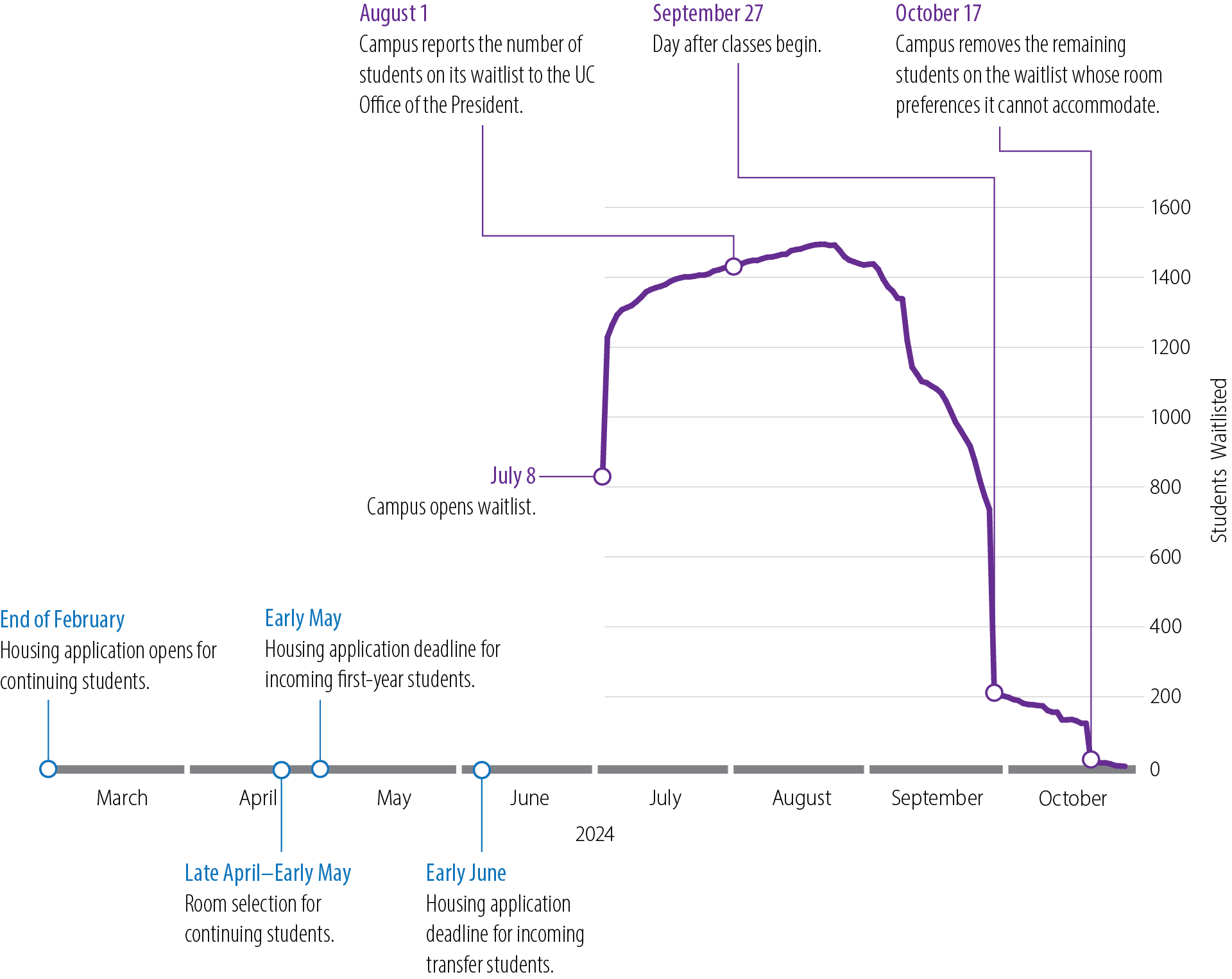

The total number of students on a campus’s waitlist will generally decline as a housing application cycle progresses for varied reasons, including that campuses offer housing to those students as beds become available. As Figure 6 shows, the total number of undergraduate students on UC San Diego’s Fall 2024 student housing waitlist began to decrease starting in late August. Based on the documentation UC San Diego provided, we determined that 358 waitlisted students, or about 22 percent, accepted a housing offer from the campus. The remaining students on the waitlist either removed themselves, were removed by the campus because they did not respond when campus staff tried to contact them, were removed by the campus because they did not update their status on the campus waitlist, declined the campus’s housing offer, or never responded to the offer. Consequently, campuses that report waitlist numbers later in their housing application cycle will generally have fewer students on their waitlists. In contrast, campuses that report those numbers earlier in their housing application cycle may have more students on their waitlists. For example, UC San Diego had nearly 1,500 undergraduate students on its waitlist at the end of August 2024, but that number was reduced to just 210 students at the end of September, the day after instruction began.

Figure 6

UC San Diego’s Fall 2024 Undergraduate Housing Waitlist Decreased Over Time

Figure 6 graphs the change in the number of undergraduate students on UC San Diego’s Fall 2024 student housing waitlist over time. The figure shows that waitlist first grows after the campus opens it in July. Then, the total number of students on the waitlist generally decreases as the housing application cycle progresses. The figure highlights key dates and events, such as the opening of the housing application for continuing students in late February, the room selection for continuing students in late April to early May, and the housing application deadline for incoming first-year students in early May. It also notes the opening of the waitlist on July 8, the reporting of waitlist numbers to the UC Office of the President on August 1, and the significant reduction in waitlist numbers by the end of September, after classes began.

Source: UC San Diego waitlist data, UC San Diego housing website, and staff interviews.

Note: UC San Diego offers a two-year housing guarantee for incoming first-year and transfer students who meet all housing deadlines and reside in campus housing beginning the Fall term of their year of admission. Thus, UC San Diego’s housing waitlist comprises students whom the campus’s housing guarantee did not cover, such as an incoming student who missed a deadline, a continuing student who had already lived in campus housing for two years, or a continuing student who voided their guarantee because they lived off campus since enrolling.

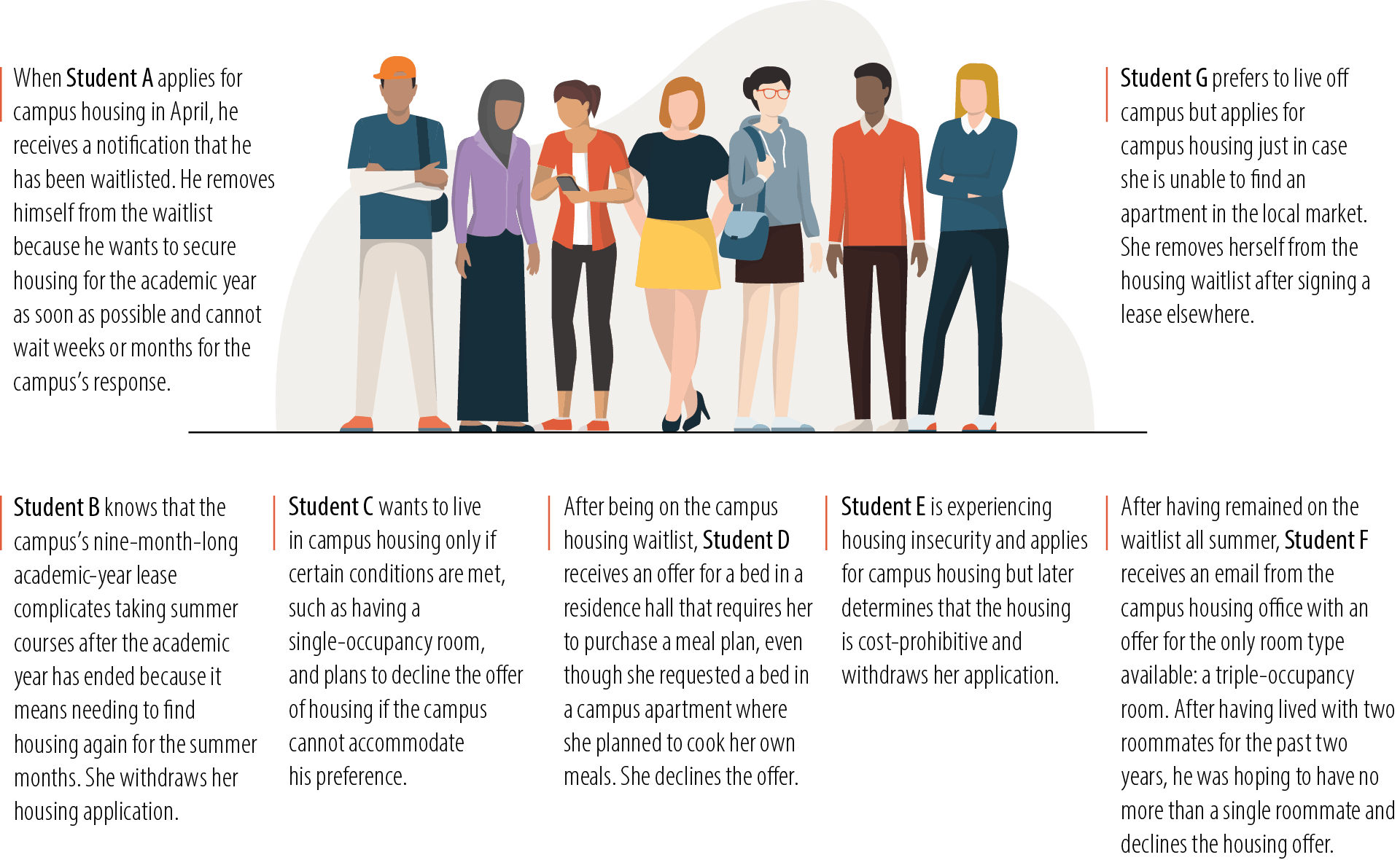

A campus may remove from its waitlist students who do not periodically verify their continued interest in campus housing, such as students who do not respond to campus emails requesting that they reply if they wish to remain on the waitlist. As Figure 7 shows, students may also withdraw their applications for campus housing for a variety of reasons, including if the campus does not offer them their preferred room type. Thus, not all the reasons that a student is removed from the waitlist are a result of the campus meeting the demand for housing. Further, housing waitlists do not include those who may want or benefit from campus housing but who do not apply. For all of these reasons, waitlist numbers alone are not a sufficient measure of unmet demand for campus housing.

Figure 7

Students Who Apply for Campus Housing May Choose to Remove Themselves From Consideration for Multiple Reasons

Figure 7 provides examples of the reasons why students might remove themselves from a campus housing waitlist. The figure outlines several scenarios involving different students. For example, Student A removes himself from the waitlist because he wants to secure housing for the academic year as soon as possible and cannot wait for the campus’s response. Student B withdraws her application because the campus’s nine-month lease complicates taking summer courses. Student C only wants to live in campus housing if certain conditions are met, such as having a single-occupancy room, and plans to decline the offer if the campus cannot accommodate his preference. Student D declines an offer for a bed in a residence hall that requires her to purchase a meal plan, as she prefers a campus apartment where she can cook her own meals. Student E, experiencing housing insecurity, finds the campus housing cost-prohibitive and withdraws her application. Student F, after being on the waitlist all summer, declines an offer for a triple-occupancy room as he was hoping for a single roommate. Lastly, Student G, who prefers to live off-campus, removes herself from the waitlist after signing a lease elsewhere. The figure emphasizes that not all removals from the waitlist are due to the campus meeting the demand for housing, and that waitlist numbers alone are not a sufficient measure of unmet demand for campus housing.

Source: Interviews with campus housing officials.

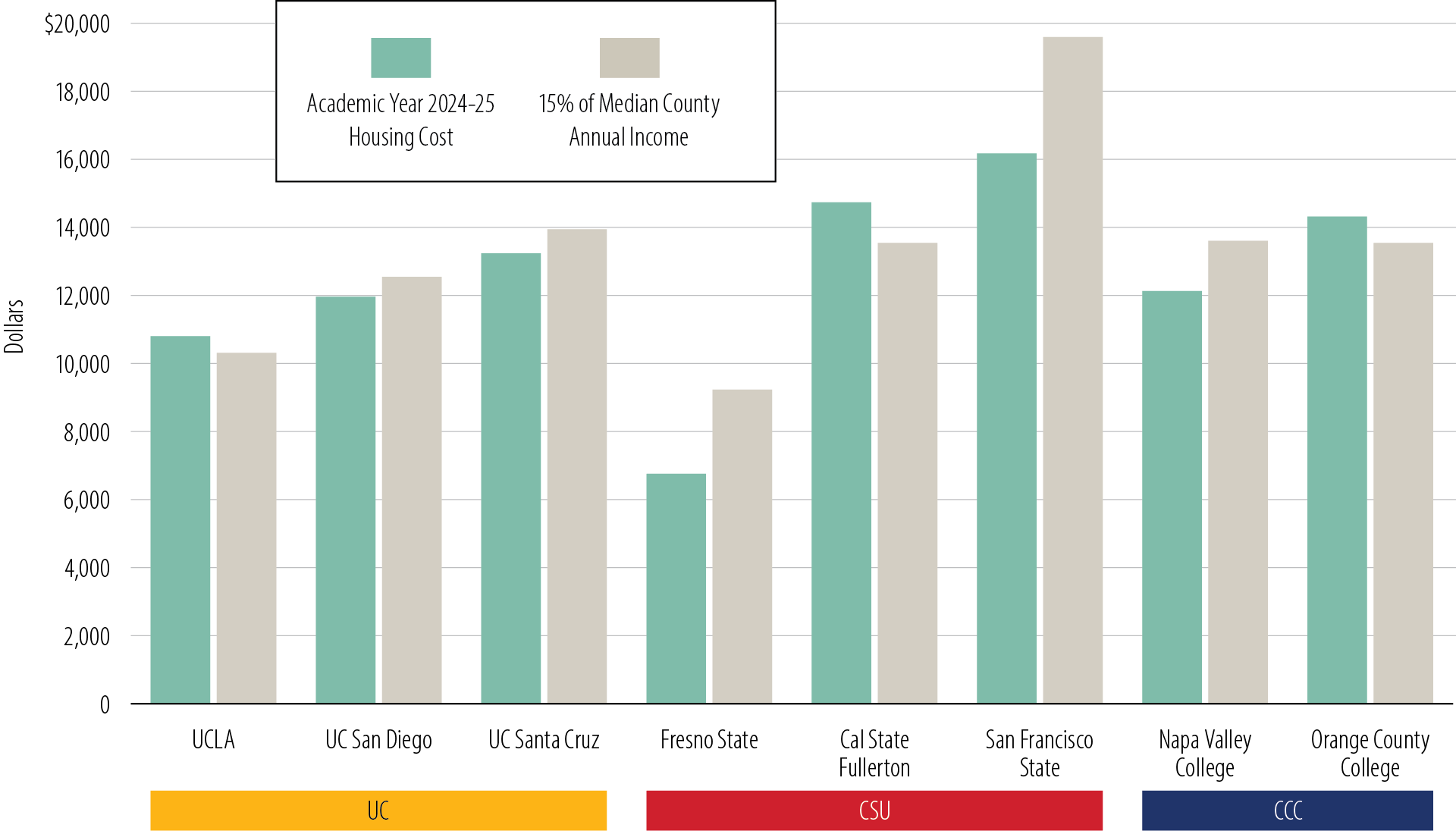

Housing Assistance

Although campus housing is generally considered affordable, students continue to struggle with increasing housing costs, both on- and off-campus, and many students have reported that they covered education and living expenses by using a type of housing assistance their college provided. As Figure 8 shows, the cost of student housing at the campuses we reviewed was generally less than or near 15 percent of annual area median income, which is the eligibility threshold for low-income housing projects funded under the Grant Program. For the purposes of this report, we refer to this type of housing as affordable. However, the California Student Aid Commission (Student Aid) reported in November 2022 that of the 17,000 students throughout the State who responded to its 2021–22 Student Expense and Resource Survey, just 16 percent indicated that they lived in campus housing. Data that colleges and universities report to the National Center for Education Statistics show that off-campus room and board costs increased from academic years 2019–20 to 2023–24 at the UC, CSU, and CCC systems by 22 percent, 21 percent, and 36 percent, respectively.

Figure 8

Campus Housing Costs Were Near or Below 15 Percent of Area Median Income at the Campuses We Reviewed That Offered Housing in Academic Year 2024–25

Figure 8 is a bar chart that provides a comparison of campus housing costs at various universities and colleges in California for the academic year 2024-25. The figure includes data from UCLA, UC San Diego, UC Santa Cruz, Fresno State, Cal State Fullerton, San Francisco State, Napa Valley College, and Orange County College. It shows that the housing costs at these campuses were near or below 15 percent of the area median income for the respective counties where the campuses are located.

Source: Campus reported housing information and the California Housing and Community Development’s (HCD) 2024 State Income Limits memorandum.

Notes: American River College does not offer campus housing.

The housing costs above reflect the cost for housing only as reported by the campuses we reviewed, which differs from the cost of food and housing combined as Appendix C shows. Further, the housing cost is the average cost for all housing types that the campus offers, as opposed to a single-occupancy unit. For the UC campuses that we reviewed, the average housing cost represents the weighted average calculated from the number of students who occupy each room type. For the CSU and CCC campuses that we reviewed, the average housing cost represents the weighted average calculated from the number of beds available in each room type.

To calculate affordability, we used HCD 2024 State Income Limits for the county where the campus is located, although we acknowledge that this is not necessarily representative of a one-person household, and is not reflective of every student’s financial situation. For example, students who receive financial aid or work-study are generally not expected to work more than 20 hours per week. Additionally, a student’s family may not reside in the county in which the student attends a college or university.

Nearly 85 percent of students who responded to Student Aid’s survey indicated that they had applied for financial aid. Generally, the financial aid office at a campus will use an estimated cost of attendance to determine the amount a student is eligible to receive in financial aid—typically composed of grants and student loans. Students can use this financial aid to cover the cost of attendance, including housing costs. Students also reported using private scholarships; grants, such as the Pell Grant and the Cal Grant; and institutional grants to cover their education and living expenses. Nevertheless, more than 61 percent of the students who responded to Student Aid’s survey reported using their own income or savings to cover their education and living expenses during academic year 2021–22. Moreover, 21 percent of students reported that they used campus-provided emergency grants to cover expenses during the same period.

The Legislature enacted statutes to expand access to campus-based support services with the goal of addressing student housing insecurity and providing for students’ other basic needs, such as food, housing, mental health, and financial needs. As we previously described, the State’s housing shortage has affected residents throughout the State, including college students. In fact, more than half of the students who responded to a May 2023 Student Aid Food and Housing Survey reported experiencing housing insecurity. Beginning in fiscal year 2019–20, the Legislature appropriated funding to the systems for partnerships and programs aimed at supporting students who are experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity. More recently, the Legislature added statutes that require each CSU and CCC campus and request each UC campus to establish a basic needs center. These centers are intended to provide a single point of contact for students seeking support.

The nine campuses we reviewed offer various types of housing assistance services, as Table 1 shows. For example, UC San Diego and UC Santa Cruz each offer an array of services for students in need, including emergency campus housing and off-campus housing, short-term emergency loans, and case management support. In contrast, Napa Valley College offers fewer housing assistance services. Campuses also partner with community-based organizations (CBOs) to provide services to supplement the housing assistance campuses offer students in need. For example, in academic year 2024–25, San Francisco State partnered with a local CBO to administer rental and utility assistance services. According to the interim director of basic needs at San Francisco State, partnering with the CBO allows this funding to be paid directly to landlords and utility providers instead of to the students, thus avoiding potential negative affects to the students’ future financial aid.

Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program

High construction and land costs are a significant barrier to building more campus housing, especially given that housing projects must be able to cover their operating costs and any associated debt service costs, while remaining affordable for students. To address this barrier, the State established the Grant Program in 2021, with the objective to provide affordable, low-cost housing options for students enrolled in the three systems of higher education. The Grant Program creates opportunities for UC, CSU, and CCC campuses to propose and apply for state support for the construction of housing projects or for the acquisition and renovation of housing projects that would provide affordable, low-cost housing options for students. In addition to other limitations, campus housing developments for students with low incomes are subject to rent restrictions under the Grant Program statute.

As of June 2025, the Legislature had amended the Grant Program six times. For example, the program initially required campuses to submit applications to the Department of Finance, which would then provide the Legislature with information on submitted proposals and a list of projects proposed for inclusion in the budget. After June 30, 2022, the program required campuses to submit their applications to their respective system office, which then ranked housing projects and provided information about them to the Legislature. As Table 2 shows, the Legislature also changed the ranking criteria after the initial round of applications for the Grant Program.

The Legislature approved nearly 40 projects for funding under the Grant Program. When it created the Grant Program, the Legislature appropriated $500 million for it in fiscal year 2021–22 and expressed its intent to appropriate an additional $750 million for it in fiscal year 2022–23. In addition, the Legislature subsequently changed the way projects are funded, as we describe later. As Table 3 shows, most of the approved Grant Program projects have not completed construction.

Audit Results

- The State’s Public Higher Education Systems Do Not Have Sufficient Processes to Identify Student Housing Needs

- Changes to the Grant Program and Limited Monitoring Threaten Campuses’ Ability to Offer Students Low-Income Housing

- Students and Their Families May Have Difficulty Understanding Education Costs and the Availability of Housing Assistance

The State’s Public Higher Education Systems Do Not Have Sufficient Processes to Identify Student Housing Needs

Key Points

- Although the State has generally regarded meeting student housing needs as the responsibility of individual campuses, legislative actions have requested or directed the University of California (UC) Office of the President, the California State University (CSU) Office of the Chancellor, and the California Community Colleges (CCC) Chancellor’s Office to undertake oversight roles in gathering information, allocating funds, and administering grant applications to address student housing needs. However, the three system offices have not assumed a strategic leadership role in planning for housing across their respective systems.

- The UC, CSU, and CCC systems have not fully assessed the extent of their unmet demand for campus housing, relying largely on incomplete measures such as waitlist data that understate the true scope of their students’ housing needs. Establishing a process to regularly assess systemwide unmet demand for campus housing would better position the systems to support campus planning efforts and provide the State with more reliable information about where campus housing is most needed.

- The CSU Office of the Chancellor’s approach to developing its statutorily required student housing plan has understated unmet demand and limited the plan’s utility for statewide planning. Specifically, the CSU Office of the Chancellor developed its student housing plan by relying on information its campuses provided that was not always current or complete. The housing plan also omitted potential market demand for new beds at 12 campuses that did not report market demand or waitlist data.

- The State’s recent efforts to expand affordable student housing highlights the potential benefits of increased collaboration between the systems. In particular, UC and CSU could share their institutional knowledge with CCC campuses that may initially face challenges establishing student housing programs. Moreover, intersegmental housing projects provide financial and geographical benefits and may result in better student outcomes. However, the systems have not prioritized identifying additional opportunities for these types of projects.

Responsibility for Student Housing Remains Decentralized Across the Systems

Student housing needs can be met by reducing housing costs, providing direct housing assistance to students, and by increasing the overall supply of campus housing. Historically, the State has generally regarded meeting student housing needs as the responsibility of individual campuses. However, as the text box shows, recent legislative actions requested or directed the system offices—the UC Office of the President, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the CCC Chancellor’s Office to undertake oversight roles in gathering information, allocating funds, and administering Grant Program applications related to student housing. One of the most significant examples of the Legislature increasing the involvement of the three systems to ensure that their campuses address their students’ housing needs was the creation of the Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program (Grant Program) in 2021. The Grant Program required the system offices to rank their respective campuses’ grant applications, oversee approved projects, and report on the status and public benefit derived from their projects. However, none of these statutes require the systems to increase the amount of campus housing to accommodate a specific number of students.

Recent Legislative Actions Supporting Systemwide Involvement in Addressing Student Housing Needs

- Assembly Bill (AB) 74 and Senate Bill (SB) 109 (2019): Established and funded rapid rehousing programs for students who are experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity at each system; required each system to allocate funding to campuses based on demonstrated need; and required each system to annually report on its use of these funds and student outcomes.

- AB 1377 (2021): Required CSU and requested UC on or before July 1, 2022, to conduct a needs assessment to determine their respective campuses’ student housing needs and to create a student housing plan that outlines how they will meet those needs with a focus on affordable student housing. The law also required CSU and requested UC to review and update their student housing plans every three years.

- SB 169 (2021): Established the Grant Program to provide one-time grants for the construction of student housing or for the acquisition and renovation of commercial properties into student housing for the purpose of providing affordable, low-cost housing options for students enrolled in public postsecondary education in the State. The CCC Chancellor’s Office, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the UC Office of the President are responsible for ranking applications for eligible proposed projects within their system, overseeing approved projects, and reporting annually on the status of project construction and for five years following project completion.*

- AB 2459 (2022): Required the CSU Office of the Chancellor and the CCC Chancellor’s Office, and requested the UC Office of the President, to annually report to the Legislature student housing waitlist information, including but not limited to the number of students on campus housing waitlists.

Source: State law.

* The initial legislation made the systems responsible for oversight and reporting, AB 183 (2022) made them also responsible for ranking eligible projects.

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed our office, as part of this audit, to determine what the system offices are doing to increase the amount of affordable housing available to students, including whether they engage in centralized planning and provide oversight or guidance to their campuses. In fact, the Government Accountability Office’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (Green Book) establishes a framework that suggests the three system offices should be responsible for ensuring that their campuses effectively address the State’s higher education goals of increasing access and improving affordability, especially with regard to the provision of student housing. Specifically, the Green Book states that an effective system of internal control increases the likelihood that an entity will achieve its objectives. It further explains that an oversight body is responsible for an entity’s strategic direction and accountability.

However, despite the State’s efforts to promote an increase in student housing, the system offices do not direct or conduct any centralized planning efforts to increase the availability of student housing. For example, since 1999, the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s policy has been to delegate the authority to each university president to directly manage the capital outlay process—including for housing projects—from initiation of preliminary funding and project design through construction and occupancy, regardless of funding source. Similarly, the CCC Chancellor’s Office historically has not played a role in planning or expanding student housing, and it only recently became involved in supporting districts with their housing needs in the context of the Grant Program. According to the UC and CSU systems, they are not in a position to direct individual campuses to undertake the construction or acquisition of student housing because they do not offer centralized capital funding for systemwide housing projects. Nevertheless, each system acknowledged that it provides capital project support to campuses as needed. For example, according to the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s assistant vice chancellor of capital planning, design, and construction (assistant vice chancellor), the system has a capital planning group that works with campuses to bring in capital projects as efficiently as possible—such as by reviewing feasibility studies or identifying construction best practices to drive costs down.

Although the UC, CSU, and CCC systems all create and issue capital outlay plans, which are informed by their respective campuses, we found that the UC and CSU plans do not identify how their proposed housing projects would contribute to accommodating the needs of current or projected students. Specifically, state law requires that CSU and requests that UC annually submit to the Legislature five-year capital outlay plans that include an explanation of how each proposed project, including student housing projects, contributes to accommodating the needs associated with current or projected student enrollments. Similarly, the CCC Chancellor’s Office must annually submit to the Legislature a five-year capital outlay plan that identifies the statewide needs and priorities of CCC campuses. However, the CCC Chancellor’s Office’s two most recent plans state that they do not completely represent the unmet capital needs of CCC campuses.

Further, our discussions with the system offices and campuses indicate that the system offices provide limited guidance to their respective campuses to increase the availability of student housing. Officials at each of the campuses we reviewed stated that their system offices do not direct them to increase housing, although some campuses noted that the systems are able to provide information or technical support that can inform campus housing decisions. For example, the senior associate vice chancellor of residential, retail, and supply chain services at UC San Diego explained that the UC Office of the President plays a large role in securing bond funding with below-market interest rates that makes it possible for the campus to achieve its goal of increasing the amount of student housing. Nonetheless, efforts to expand student housing remain the responsibility of individual campuses, with the system offices providing support to them as needed.

Lastly, the three systems do not establish systemwide housing goals; instead the campuses define their own objectives. Officials at each system stated that they do not have concrete goals related to a specific number or percentage of students who they would like to see housed or the number of beds they would like campuses to create. According to the UC Office of the President’s associate vice president of energy and sustainability (associate vice president), the campuses are in the best position to establish their housing goals because they directly manage these programs and understand the needs of their students.

This decentralized approach has resulted in housing goals that vary across the campuses we reviewed. All of the campuses we reviewed have established housing goals, with the exception of American River College, which does not currently offer campus housing. However, only the three UC campuses have established formal goals to increase the amount of affordable student housing. Some campuses developed specific and measurable goals, such as providing housing guarantees for certain student populations. For example, in UCLA’s 2016–2026 Student Housing Master Plan, the campus established four housing goals, including a housing guarantee to all incoming first-year students and new transfer students. According to the chief of staff and director of UCLA’s housing and hospitality administration, the campus achieved its goal in Fall 2022 to guarantee four years of campus housing to all entering first-year students. Officials at UCLA asserted that it is the first UC campus to make and achieve such a commitment.

Other CSU and CCC campuses we reviewed did not have specific goals but had general aspirations—such as expanding access or affordability. For example, Napa Valley College’s goals, shown in the text box, were neither specific nor measurable. Further, the campuses reported varying degrees of success with meeting their housing goals. If the Legislature intends for the systems to assume a stronger leadership role in overseeing and planning student housing to ensure that the systems’ student have adequate affordable housing, the Legislature should clarify this expectation in law and specify the appropriate responsibilities for systemwide oversight.

Napa Valley College’s Student Housing Goals

- Provide an affordable, quality on-campus living experience.

- Promote an even more engaged and diverse population.

- Enhance campus engagement.

- Support recruitment and retention of students, faculty and staff.

- Extend campus integration with the community.

Source: Napa Valley College Board of Trustees documentation and interviews with Napa Valley College’s senior dean of student affairs.

The Legislature Should Require the Systems to Regularly Assess Their Unmet Demand for Student Housing

Although the systems have historically used a decentralized approach to address student housing, there are many ways in which they would benefit by better understanding the extent of their campuses’ student housing needs. Best practices issued by the Government Finance Officers Association state that identifying needs is the first step in prudent capital planning. Scion Advisory Services, one of the largest operators of off-campus student housing globally, has similarly underscored the importance of assessing unmet demand when planning student housing projects. It particularly emphasized the importance of determining the number of students who want or would benefit from campus housing but do not receive it, regardless of whether they apply.

Despite the critical role that unmet demand plays in guiding housing development, each of the systems relies upon its campuses to understand and define their own housing needs rather than establishing a systemwide understanding of demand. For example, the UC Office of the President and the CCC Chancellor’s Office acknowledged that they do not conduct comprehensive assessments of housing demand across their respective systems and are not in the position of directing campuses to construct or acquire new housing. The UC Office of the President associate vice president emphasized the system’s role in providing guidance within a federated system in which each campus leads its own initiatives. The director of student housing at the CCC Chancellor’s Office explained that he has calculated unmet demand for applicants of the Grant Program, but that the purview of his unit has been to oversee the Grant Program’s projects rather than to undertake a larger assessment of unmet demand across the system. Officials from both of these system offices emphasized their role as guiding campus-led projects to fruition, rather than identifying the need for new housing.

In contrast, officials at the CSU Office of the Chancellor asserted that they assessed housing demand across the CSU system in the form of their legislatively mandated student housing plans. Specifically, state law required the CSU to conduct an assessment to determine the projected student housing need by campus, and in September 2022, it issued the required report on this assessment. However, as we explain in the next section, we found that the methods the CSU used may understate unmet demand throughout its system. As a result, this system—like the other two systems—lacks a complete and comparative understanding of where student housing is most needed across their respective campuses.

In part because California’s higher education systems have not established a sufficient process to assess unmet demand, external stakeholders and the systems commonly rely on student housing waitlist data as a proxy for representing unmet demand. Since 2022, state law has required the CSU Office of the Chancellor and the CCC Chancellor’s Office to report annually to the Legislature each campus’s number of students who request student housing, if available, and the number of students on housing waitlists. State law only requests that the UC Office of the President submit such a report.2 Legislative committee analyses of AB 2459—the law mandating these reports—explained that because campuses did not routinely provide data on occupancy rates and waitlists for student housing, the Legislature was not aware of whether campuses were meeting student housing needs. These analyses further stated that gathering and using these data would allow for more oversight and assessment of student housing needs across systems and provide students with information with which to make better-informed housing decisions.

However, student housing waitlist numbers are not reliable indicators of unmet demand because the systems each have their own methodology and timing for collecting or reporting them. As we explain in the Introduction, the number of students on a campus’s waitlist will generally decline as the campus progresses through its housing application cycle. Therefore, in the absence of a standard methodology that all systems use, the numbers they collect will be representative of different points in the various housing cycles. These inconsistencies in the timing of the data limit their usefulness for understanding or comparing student housing demand statewide. For example, when the CSU Office of the Chancellor collected student housing information for its Fall 2024 report, campuses provided this information as of the time of the request—September 2024—after the start of the academic year. As we explain in the Introduction, because campuses undergo their housing assignment process before the academic year begins, waitlist data from September may underestimate unmet demand for campus housing. In contrast, the UC Office of the President required semester campuses to report their waitlist numbers as of July 1 and quarter campuses to report their waitlists as of August 1—both roughly two months before the start of their academic terms. In addition, the CCC Chancellor’s Office requested campuses to provide their student housing information before November 2024 but did not specify a point in time that the campuses’ information was meant to represent.

In addition, relying solely on waitlist numbers may understate the full extent of demand for student housing because they do not include students who do not apply for campus housing. For example, students who are interested in campus housing may not apply if they perceive that housing is unavailable, unaffordable, or highly competitive. There is evidence to support the fact that campuses are aware that students’ perception of availability affects whether they apply. Specifically, UC San Diego reported to the UC Office of the President that its Fall 2022 undergraduate waitlist was underreported because continuing students did not apply after they perceived that the campus did not have the capacity to accommodate them.

Additionally, a campus’s unmet demand for housing may not become evident until new housing coincides with an uptick in applicants. UC San Diego’s director of strategic partnerships and housing allocations explained that after the campus opened a new building in its graduate and family housing portfolio in Fall 2017, the number of waitlisted applicants was actually larger despite the property offering 1,350 new beds. This example further demonstrates that the mix of housing options in a campus’s housing portfolio may affect whether a student decides to apply for a bed. For example, campus housing officials acknowledged that if a student prefers a single-occupancy room but perceives such an assignment is unlikely, the student might decide not to apply at all. The associate vice president of housing, dining, and conference services at San Francisco State stated that these perceptions have become more prolific over the past several years, attributing students’ reservations about applying for housing to social media comments about other students’ being waitlisted. Moreover, the California State Student Association authored a statement in April 2025 expressing concern that the existing metrics that campuses use to assess demand for new housing often exclude the students with low incomes and insecure housing who did not apply for campus housing.

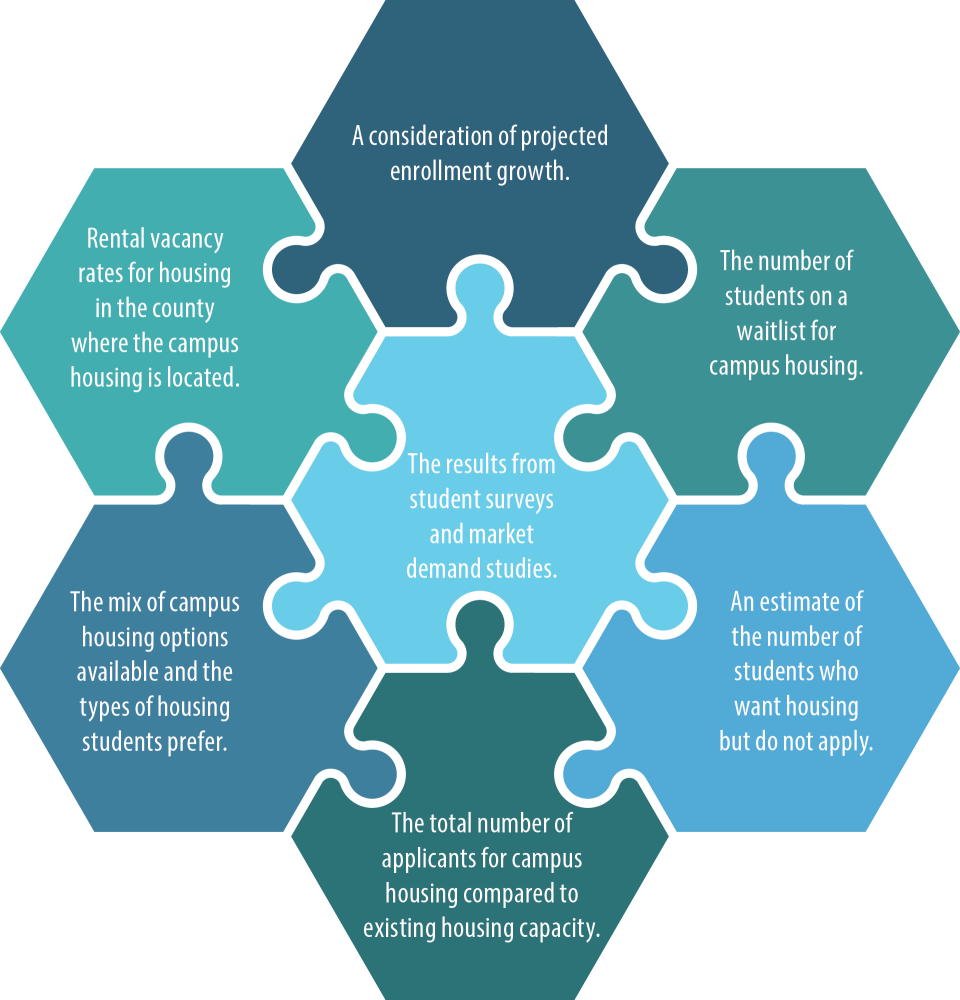

Because waitlists reflect only a portion of students who want or need housing, they are not sufficient on their own to assess total unmet demand. Consequently, a more comprehensive process is necessary to more accurately understand and respond to student housing needs. To this end, the systems should establish a process to regularly assess their unmet demand for campus housing. With such a process in place, the systems would be better positioned to support campus planning efforts and provide the State with more reliable information about where campus housing is most needed. Moreover, the systems would be able to hold their campuses accountable for addressing their students’ needs. To calculate a more complete picture of unmet housing demand, including students who do not apply, the systems could consider incorporating a range of metrics such as projected enrollment growth, market demand studies, and information from student surveys, as Figure 9 suggests. For example, the use of surveys can help system and campus officials better understand students’ perspectives about housing needs and availability. In fact, CSU’s 2025 housing plan acknowledged that waitlist numbers alone were insufficient and indicated that a more sophisticated survey tool would help to define unmet demand.

Figure 9

An Assessment of Unmet Demand Should Include a Variety of Helpful Metrics

Figure 9 outlines helpful metrics for assessing unmet demand for student housing, including projected enrollment growth, waitlist numbers, and survey results. Market demand studies and estimates of students who want housing but do not apply should also be considered. The total number of applicants compared to existing housing capacity can highlight the gap between supply and demand. The figure also supports considering the mix of campus housing options available and the types of housing students prefer. Lastly, rental vacancy rates in the county where the campus is located can offer helpful context for the local housing market.

Source: State law, the 2022 CSU Office of the Chancellor’s housing plan, and analysis of campuses’ student housing processes.

However, the campuses we reviewed that offered campus housing prior to Fall 2024 did not use campuswide surveys to inform their understanding of unmet student housing demand by asking focused questions, such as whether students faced difficulties in obtaining housing or would choose to live in campus housing if it were available. Instead, campus housing offices generally surveyed only students who were already living in campus housing about their experiences. Further, only four of the campuses included affordability-related questions—such as asking whether student housing was a good value—and none explicitly asked whether students had difficulty affording housing or had to forgo other necessities to make payments. One campus we reviewed, San Francisco State, conducted a survey that included some students who applied for student housing but later withdrew. Among those respondents, the most common reason for not living in student housing was to save money on rent, although it is unclear from the survey results whether those students ultimately did. Additionally, none of the campuses we reviewed had assessed the number of students who could afford off-campus housing.

The system offices are uniquely situated to assess demand across campuses, identify trends, and inform statewide strategies. By establishing a process to regularly assess their unmet demand, the systems would be better equipped to align future housing efforts with actual student needs and to support campuses and the State in making informed decisions about where to invest in campus housing. Importantly, leaders at all three systems acknowledged that undertaking a state-funded systemwide assessment of unmet demand could help identify where the need for housing is greatest, although they expressed reservations about the ability to act on such information, beyond sharing it with campuses. Further, each campus indicated the need for additional state funding to develop a more robust and regular assessment of unmet demand for student housing. If the State intends for the systems to assume a stronger leadership role in undertaking an assessment of unmet demand, the Legislature should specify this expectation in law.

The CSU Office of the Chancellor Has Not Fully Assessed Its Students’ Housing Needs

Although no system has a comprehensive understanding of its campuses’ unmet demand for student housing, the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s statutorily required student housing plan represents a recent effort to evaluate this demand more fully. Specifically, the Legislature required the CSU Office of the Chancellor and requested the UC Office of the President to each create a plan that outlined how it would meet its projected student housing needs (student housing plan), as the text box describes. In response, the CSU Office of the Chancellor issued its first student housing plan in 2022 and an updated plan in 2025.3 Although CSU acknowledges in its plans that assessing students’ housing needs encompasses more than just unmet demand, the two housing plans represent CSU’s efforts to analyze its students’ housing needs across the system. As a result, CSU estimates in its most recent housing plan that by Fall 2030 nearly 39,000 students will need some form of housing assistance, such as financial aid or housing grants, student services and support programs, or subsidized housing. Of these students, CSU determined that market demand for student housing could support about 15,400 new beds.

Statutory Provisions for Needs Assessments and Student Housing Plans

State law required the CSU Office of the Chancellor and requested the UC Office of the President to do the following by July 2022:

- Conduct a student housing needs assessment, by campus, for fiscal years 2022–23 through 2026–27, that accounts for the following elements:

- Projected enrollment growth.

- The goal of closing the degree gap.

- Create a student housing plan that does the following:

- Outlines how they will meet the projected need, by campus, as identified by the needs assessment.

- Specifies the actions to be taken for fiscal years 2022–23 through 2026–27.

State law also requires the CSU Office of the Chancellor and requests the UC Office of the President to review and update every three years after July 1, 2022, the student housing plan described above and include the specific actions to be taken in the next five fiscal years.

Source: State law.

However, the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s determination of unmet demand may be understated because its assessment of student housing needs was not thorough. It developed its student housing plan by relying on information its campuses provided that was not always current or complete. For example, to determine its total systemwide demand in its 2022 and 2025 student housing plans, the CSU Office of the Chancellor requested its campuses to provide the results of any existing market demand studies that they had independently conducted or waitlist information. In response, only eight of the system’s 23 campuses provided results of market demand studies to inform the system’s 2025 student housing plan. However, two of those eight studies were conducted in 2018, and two other studies did not indicate the period in which they were conducted.

Although officials at the CSU Office of the Chancellor assert that these studies were recent and sufficient to guide policy, the system had requested its campuses provide any recent market studies that were completed since 2019, suggesting that the studies were or may have been outdated. Moreover, outdated information is problematic for measuring demand. For example, since the COVID-19 pandemic, gross median rent in California has risen, and more students have reported experiencing housing insecurity—increasing from 36 percent of surveyed students in academic year 2018–19 to 53 percent in academic year 2022–23 according to the California Student Aid Commission (Student Aid). These increases suggest that the number of students who might benefit from campus housing has likely also increased since 2020.

Officials at the CSU Office of the Chancellor told us that in addition to the demand studies, they used Fall 2024 waitlist information from four CSU campuses—Fresno State; California State University, Long Beach (Cal State Long Beach); California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (Cal Poly Pomona); and California State University, Northridge to estimate market demand.4 However, as we previously describe, waitlist numbers may understate the demand for campus housing. For example, the CSU Office of the Chancellor requested Fall 2024 waitlist information from its campuses in late August 2024 but did not specify the date at which they should have recorded their waitlists. According to the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s director of long-term finance, the system did not specify a date because the campuses’ processes vary and the CSU Office of the Chancellor wanted to provide flexibility for campuses to supply the most accurate information. As a result, the CSU Office of the Chancellor used waitlist information the four campuses reported as of September 2024. This date was after or near the start of the Fall term, when their waitlist numbers were likely among their lowest. Using this waitlist information likely resulted in CSU’s 2025 housing plan underreporting demand by roughly 1,100 waitlisted students.

The CSU Office of the Chancellor’s approach to developing its housing plan also omitted potential market demand for new beds at 12 campuses that did not report market demand studies or waitlist data. According to officials at the CSU Office of the Chancellor, these campuses are adequately meeting their demand or have vacant beds in their housing stock. However, two of these campuses—Cal State Monterey Bay and Chico State—reported in September 2024 that they had a combined total of more than 700 students on their waitlists. Further, the CSU Office of the Chancellor reported in its 2025 housing plan that Cal State Monterey Bay and Chico State experienced housing occupancy rates of 98 percent and 99 percent respectively for Fall 2024, suggesting that they may be experiencing or may soon experience unmet demand for housing.

Additionally, campuses with vacancies may still have demand for specific types of units or rental rates that are not available in the existing housing stock. For example, housing officials at UC San Diego observed a significant increase in demand after opening new types of housing. Despite not being in the CSU system, this example illustrates that opening new types of housing may increase demand. When we discussed with officials at the CSU Office of the Chancellor about the system’s exclusive use of available demand studies and waitlist data and why they excluded other considerations to inform its determination of market demand, the assistant vice chancellor stated that CSU believed the underlying data sources were sufficient to perform the analysis in response to the Legislature’s request to identify how CSU’s housing plan could support addressing the degree gap. Nonetheless, the CSU Office of the Chancellor could incorporate other metrics, which Figure 9 describes, to improve its assessment of market demand in the future.

The CSU Office of the Chancellor identified in its 2022 housing plan other potential ways it could improve its overall assessment of student housing needs, but it has not taken action to address those areas. For example, the 2022 housing plan states that better data collection would include clearer information on the number of students in need of housing who have low incomes or are experiencing housing insecurity. Similarly, the system indicated in its 2022 housing plan that a more sophisticated survey tool would be needed to estimate the number of students with low incomes who are not accommodated on campus because the campus lacked capacity or rents were too high. However, in its 2025 housing plan, CSU again used outdated data in these two areas that may have affected its overall assessment of student housing needs.

Lastly, the CSU Office of the Chancellor stated in its 2022 housing plan that it would create a systemwide committee of various staff, including housing, financial aid, and capital planning and construction staff, in an effort to improve its future housing plans. It stated that this committee would examine student needs assessments and research, analyze enrollment trends and graduation data, and evaluate short- and long-term housing demand and affordability studies. However, the CSU Office of the Chancellor did not address this commitment in its 2025 housing plan. When we asked why the system did not form the proposed committee, neither the assistant vice chancellor nor the university planner could provide an explanation. Forming a committee of this nature would enable the CSU Office of the Chancellor to focus on resolving the issues we identified and improving the utility of its student housing plan.

Greater Intersegmental Collaboration Could Expand Student Housing Opportunities and Improve Efficiency

The State’s recent efforts to increase the amount of affordable student housing highlights the potential benefits of more collaboration among the systems, especially between CCC and the other two systems. Grant Program projects that increase the inventory of student housing at the three systems can help them individually foster future enrollment growth and can have a positive influence on their students’ academic experience, financial stability, and overall well-being. However, intersegmental projects that involve a CCC campus partnering with a UC or CSU campus may offer additional benefits. Specifically, CCC campuses with little or no experience in operating campus housing could benefit from the institutional knowledge that UC and CSU campuses have acquired. At the same time, housing students from multiple systems together could help increase transfer rates and close the degree gap.

These benefits may have been the rationale behind the Legislature’s general interest in intersegmental facilities—a required element of the systems’ annual capital plans under statute. In fact, when the Department of Finance made its initial project recommendations to the Legislature in March 2022, those recommendations prioritized support for eligible construction grant applications that reflected an intersegmental housing arrangement. Ultimately, the systems and campuses submitted six intersegmental projects, one of which the Department of Finance determined was ineligible. Of the five eligible intersegmental projects, the Legislature approved the four projects listed in the text box. The fact that the Legislature approved nearly all eligible intersegmental projects further supports legislative interest in intersegmental housing projects.

Approved Intersegmental Grant Program Projects

- UC Merced and Merced Community College

- UC Santa Cruz and Cabrillo Community College

- San Diego State and Imperial Valley Community College

- UC Riverside and Riverside Community College

Source: State law.

Institutional knowledge about student housing at UC and CSU could support CCC campuses that may initially face challenges establishing student housing programs. The three systems’ campuses are currently responsible for identifying potential partner campuses at the other systems, identifying and contacting the appropriate officials at those campuses, and initiating intersegmental projects on their own. CCC campuses that do not have existing campus housing, dedicated housing staff, or relationships with nearby UC and CSU campuses may find this type of outreach and planning difficult as they are likely not familiar with many of these steps. For example, according to the Los Rios Community College District executive vice chancellor of finance and administration, American River College considered pursuing an intersegmental opportunity with Sacramento State but did not have a preexisting relationship with that campus that it could leverage when the Grant Program was implemented.

The UC Office of the President, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the CCC Chancellor’s Office are in a better position to be aware of geographic dynamics affecting multiple campuses, systemwide housing demand, and available resources. They are also better positioned to share that information with the other system offices to enable more agile and effective project identification. To jointly address unmet need throughout the State, the system offices should be familiar with their own campuses’ housing goals and demand for housing when collaborating with other systems. Increased system-level planning would help the three systems to identify efficient projects that could serve more than one campus.

Intersegmental collaboration may also diversify the possible fiscal and geographic resources the campuses use to support their housing projects. Although state law has long provided the UC Regents and the CSU Board of Trustees with the authority to issue revenue bonds to fund housing projects at their campuses, the governing boards of individual CCC districts have similar authority. In a November 2021 presentation to the Legislature on student housing, the Legislative Analyst’s Office stated that individual housing projects may struggle to cover their operating and debt service costs while remaining affordable for students and that a campus may sometimes use other campus housing facilities to subsidize new housing facilities to help keep rents affordable. The student housing director at the CCC Chancellor’s Office stated that it is beneficial and efficient for systems and campuses to share resources, institutional knowledge, and the cost and risk associated with building housing. Similarly, the CSU Office of the Chancellor’s assistant vice chancellor stated that CSU campuses would benefit from diversifying their projects’ funding sources through partnerships with CCC campuses that may be able to issue local revenue bonds.

Beyond expanded financing opportunities, the UC and CSU campuses, some of which do not have room to build more housing, would benefit from the increased land available at CCC campuses. According to UC Santa Cruz’s associate vice chancellor of colleges, housing, and educational services, the joint project between UC Santa Cruz and Cabrillo Community College will allow UC Santa Cruz to create more housing capacity for its students without the challenges associated with building on its own campus. The associate vice chancellor specifically mentioned geological instability and the local regulatory environment as challenges. Additionally, the project application indicates that the campuses identified the Cabrillo Community College Aptos location as the preferred site because it eliminates the need for land acquisition or related costs, and because it is near a connection point via the Santa Cruz Metro. UC and CSU campuses located in densely populated areas of the State may similarly benefit from available land at nearby CCC campuses.

Moreover, building additional intersegmental student housing projects could improve student success and outcomes. As we discuss in the Introduction, living on campus provides positive academic benefits for students. Further, intersegmental campus housing can provide housing to students who are seeking to transfer from a CCC campus to a four-year school. For example, UC Riverside and Riverside City College are building a joint housing project on UC Riverside’s campus that will provide affordable housing to 652 students at UC Riverside and Riverside City College. As a result, Riverside City College students living in the new building may not need to move if they transfer to UC Riverside.