2024-108 Alameda County Department of Children and Family Services

Delayed Investigations and Support Services Risk the Health and Safety of Youth

Published: September 23, 2025Report Number: 2024-108

September 23, 2025

2024‑108

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Alameda County Department of Children and Family Services (department) regarding its role in ensuring the health and safety of youth in the county’s foster care system. In general, we determined that the department did not always initiate investigations of alleged child abuse and neglect referrals within the prescribed time frames, did not always ensure that foster youth received timely critical physical and mental health services, and did not always ensure that youth maintained connection with family members.

The department must initiate investigations within one day when youth are in imminent risk (immediate referrals) and within 10 days when youth are not at imminent risk (non‑immediate referrals); however, the late initiation of such investigations has increased since fiscal year 2019–20. In fiscal year 2023–24, the department initiated investigations of 11 percent of immediate referrals and 48 percent of non‑immediate referrals after the required time frames. Furthermore, the department did not complete investigations within the prescribed 30 days after initiation, and it took the department an average of 105 days to complete investigations for about half of all non‑immediate referrals in fiscal year 2023–24. Although delays in initiating investigations of the referrals that we selected for review were beyond the department’s control—when, for example, the department was unable to contact a family member after repeated attempts—the department could not always demonstrate why its completion of investigations took so long. We acknowledge that the department has faced high job vacancies, which has resulted in large caseloads for its staff in the Emergency Response Unit—the unit responsible for conducting investigations.

Because it lacked necessary documentation, the department could not demonstrate or did not ensure that youth received needed services in a timely manner. Inconsistent documentation leaves the department unable to know whether its staff have made adequate efforts to ensure that youth receive services in a timely manner. Similarly, we found that the department’s documentation did not include information about its efforts to identify, locate, and notify all relatives who could serve as potential caretakers or to engage youth with family members to expand the youths’ potential support networks.

Without timely investigations and thorough documentation, the department runs the risk of leaving youth in potentially unsafe circumstances or of not providing vital services that youth in its care require for their well‑being, family connections, and successful transition into adulthood.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CCWIP | California Child Welfare Indicator Project |

| CDSS | California Department of Social Services |

| CFE | Center for Excellence |

| CFT | Child and Family Team |

| CHDP | Child Health and Disability Prevention |

| ER Unit | Emergency Response Unit |

| IEP | Individualized Education Plan |

| ILT | Interagency leadership team |

| IPP | Individual Program Plan |

| MOU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| RBA | Results‑based accountability |

| SDM | Structured decision making |

| STRTP | Short Term Residential Therapeutic Placement |

| WCCC | WestCoast Children’s Clinic |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

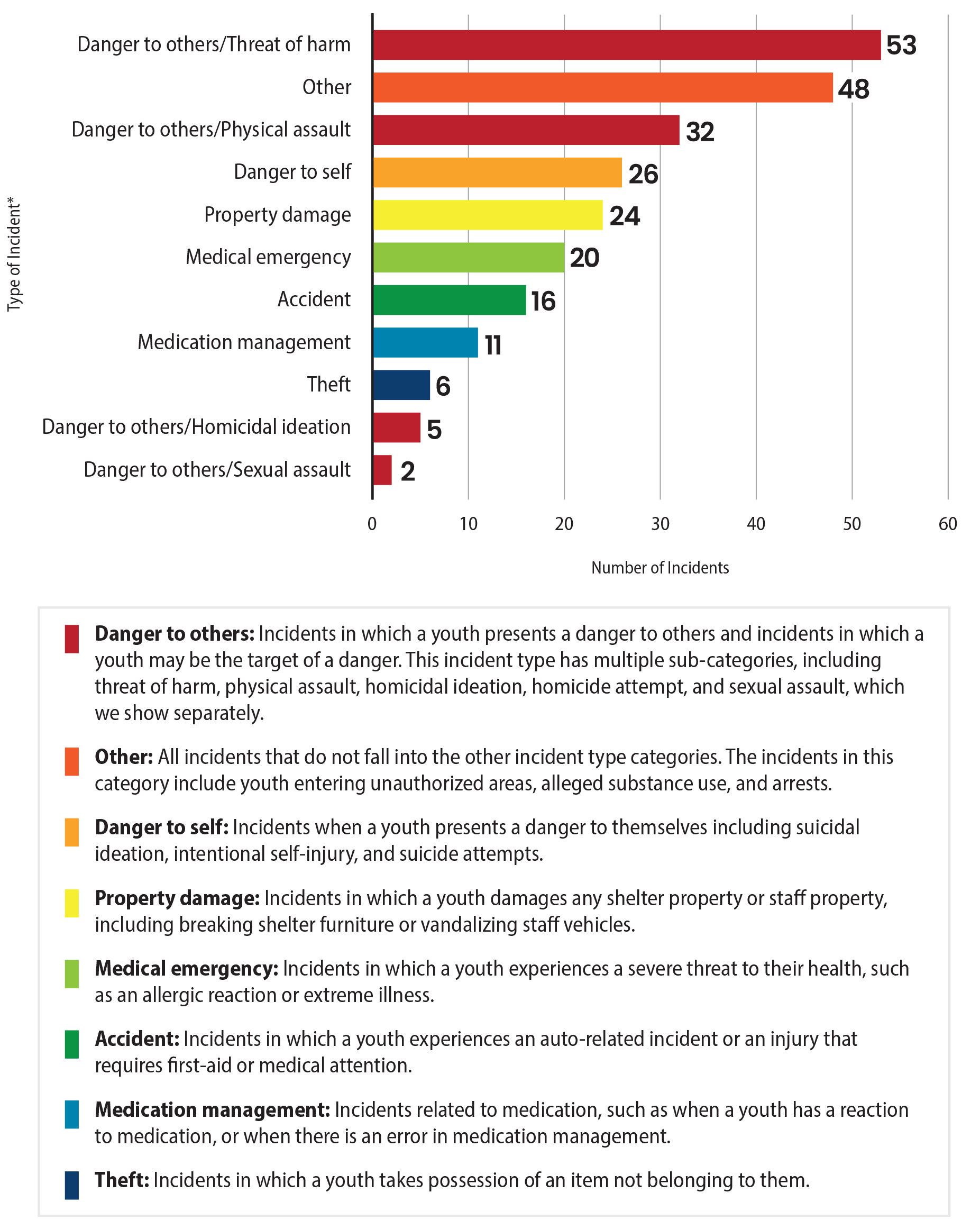

The Alameda County Department of Children and Family Services (department) is responsible for protecting the more than 300,000 youth who live in the county by providing child abuse and neglect prevention services, responding to child abuse and neglect reports, and providing needed services to youth in the foster care system. From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, the department received nearly 57,000 reports of alleged child abuse and neglect. When the department receives a report of alleged child abuse and neglect through its centralized hotline, an intake worker may initiate a referral for investigation. If the referral indicates that youth are in imminent danger of physical pain, injury, disability, severe emotional harm, or death (immediate referral), the department must conduct an in‑person investigation within 24 hours of receiving the referral. When an allegation could constitute abuse or neglect, but the youth is not at imminent risk (non‑immediate referral), state law requires an in‑person investigation within 10 days. A child welfare worker then performs an investigation to evaluate the risk of the youth’s safety and assesses the possible need for out‑of‑home placement. In our review of the timeliness of investigations of alleged child abuse and neglect referrals and the provision of services to foster youth, we found that the department did not initiate about half of its investigations within the prescribed time frames, did not ensure that foster youth received timely critical physical and mental health services, and did not adequately report critical incidents that occurred at its Transitional Shelter Care Facility (transitional shelter). Until the department addresses these significant shortcomings, it cannot ensure that it is taking sufficient action to address the health and safety needs of Alameda County’s youth.

High Job Vacancy Rates and Caseloads Have Contributed to Delays in Investigations of Alleged Child Abuse and Neglect

From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, the department did not consistently initiate or complete investigations of child abuse and neglect referrals within the required time frames, leaving youth in potentially unsafe situations. The department initiated investigations after the prescribed 24‑hour time frame for 5 percent to 11 percent of the more than 1,000 immediate investigation referrals per year from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, and initiated investigations after the prescribed 10‑day time frame for 17 percent to 49 percent of about 2,000 non‑immediate investigation referrals per year during the same period. For example, in fiscal year 2022–23, the department initiated investigations of 1,030, or 49 percent, of the non‑immediate referrals after 10 days, while the average number of days to initiate these late investigations was 187 days. We also found that after initiating investigations, the department did not always complete them within the required time frames. For the referrals it investigated, the department closed investigations of between 51 and 59 percent of immediate referrals per year and between 59 and 75 percent of non‑immediate referrals per year after the prescribed 30‑day time frame. We found that fiscal year 2021–22 had the longest average number of days to close late investigations with the department closing investigations of about 1,000 immediate referrals in 407 days, on average.

The department attributed the delays to its child welfare worker vacancy rates and high caseloads. The department also noted that the intense and often traumatic nature of the work, with exposure to challenging situations involving youth and families, can lead to stress and burnout among child welfare workers. The department’s child welfare workers whom we interviewed, and the responses to a department survey of employees completed in 2023, also identified stress as one of the most significant challenges child welfare workers face. Our review showed that from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25, the department’s vacancy rates doubled from 17 percent to 34 percent for child welfare workers and more than doubled from 8 percent to about 18 percent for supervisors. The many vacancies in Alameda County have resulted in child welfare workers at the department’s Emergency Response (ER) Unit having caseloads higher than the guideline that recommends 15 new cases per month. The ER Unit plays a critical role as it is responsible for investigations of immediate referrals. These vacancies have reduced the department’s ability to meet the needs of the county’s youth and families. Even though the department has implemented some strategies to address its vacancies—such as using involuntary staff transfers to help address open referrals and reduce caseloads in its ER Unit—we believe that the department could hire more child welfare workers in its ER Unit in the Child Welfare Worker I position, which only requires the individual to have earned a bachelor’s degree. It could also implement a mandatory practice that new staff shadow more experienced child welfare workers to reduce the time supervisors spend training new staff.

The Department Has Not Ensured That Interagency Partners Provide Timely Services, Risking the Health and Safety of Foster Youth

To provide foster youth with coordinated and trauma‑informed services, Alameda County established a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in May 2022 with public and private partners, including the Alameda County Behavioral Health Department, the Alameda County Office of Education, the Regional Center of the East Bay, and the Alameda County Probation Department. The MOU directs these interagency partners to provide youth with certain services, such as educational, developmental, and mental and behavioral health services, and it requires the partners to coordinate referrals, screening, eligibility, and authorization of therapeutic care for youth with complex emotional and behavioral needs. The department could not ensure that youth received needed services in a timely manner because it did not consistently document and track the frequency and the timeliness of services provided by its interagency partners or the department’s contractors. To determine whether the department provided timely services, either directly or through its interagency partners, we reviewed 36 case files in which youth were referred to 125 specific services. Sixty‑five of these 125 referred services lacked the necessary documentation, such as treatment summaries and detailed notes about when services were provided, to determine whether the youth received timely services. Although child welfare workers generally made their monthly visits to foster youth as required, existing contact notes from those visits included inconsistent or inadequate details about the frequency and dates of services youth received. For example, for six of the 10 sexual health education services we reviewed, the department lacked sufficient documentation to demonstrate when the youth received the service.

Additionally, when we could evaluate timeliness, the services were delayed from an average of three months for health services to more than a year for sexual health education services. For example, youth should receive health and dental services within 30 days of a court’s determination to remove youth from the home. Of the 28 health services that we reviewed for timeliness, 11 were delayed by an average of 85 days after the 30‑day time frame. Although the causes of most of the delays appear to be circumstances outside of the department’s direct control—such as delays in families’ receiving Medi‑Cal cards and youth who were absent from their respective placement without permission—inconsistent documentation leaves the department unable to know whether staff have made adequate efforts to ensure that youth receive services in a timely manner. Finally, the department’s MOU does not require partner agencies to provide necessary documentation of services to be provided and when they were actually provided. Insufficient documentation leaves the department without the information necessary to ensure that the terms of its MOU are appropriate for accomplishing the goal of a coordinated, integrated, and effective delivery of services for children, youth, and families.

The Department’s Efforts to Connect Youth With Family and Keep Them Safe in Temporary Shelter Have Been Inadequate

The department did not prioritize efforts to ensure that foster youth had ongoing connections with family members. When a court orders the removal of a youth from the custody of their caretaker for reasons necessary to protect the youth, the department should, within 30 days, conduct an investigation to identify, locate, and notify all relatives of their option to provide support or possible placement for the foster youth with the relative. The department reports to the court every six months on the status of the case, which should also include a discussion about the department’s efforts to enhance the youth’s family connections. In all five cases we reviewed, we found that the department’s report to the court did not include information about the efforts the department took, such as asking the youth about their relatives and contacting all identified relatives by telephone, email, or through in‑person visits, to identify, locate, and notify all relatives who could serve as potential caretakers. We also found that the department did not perform continued efforts to engage youth with family members to expand the youth’s potential support networks (family finding and engagement).

The department operated a transitional shelter until July 2024. The California Department of Social Services (CDSS) allowed the department to house at this transitional shelter, for up to 72 hours, youth who did not have immediate placement options and were awaiting stable placement. However, youth at this transitional shelter may have faced risks, including assaults and drug use, while they were at the facility or away from the transitional shelter without authorization (missing from care). The transitional shelter cannot force youth to stay in the shelter and some of the youth may leave the transitional center at their own discretion and go missing from care. Our review of 166 critical incidents—such as injuries that require medical attention or those in which youth were missing from care—that the department reported to CDSS from August 2020 through July 2024 found that the most prevalent critical incidents included those in which a youth threatened to assault another youth or staff members. Further, our review of critical incident reports found that youth who were missing from care were often involved in critical incidents that included drug or alcohol use. Further, CDSS’s inspection reports from fiscal years 2020–21 through 2023–24 identified deficiencies related to the department’s reporting of critical incidents.

Other Areas We Reviewed

In addition, we reviewed the department’s compliance with training requirements for child welfare workers and supervisors. From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, many department staff did not complete the required training, citing issues of workload, scheduling conflicts, and staff absences. We also reviewed the department’s contracts with providers of services for youth to determine whether the contracts provided time frames for service delivery or performance metrics for timely delivery of services, and we found that most contracts did not include such metrics for timeliness. Without the timeliness metrics, the department may not be able to track whether its contractors provide service within the agreed upon time frames. However, the department agreed that having performance metrics for timeliness in its contracts would ensure better provision of services to foster youth.

To address these findings, we have made recommendations to the department that it should periodically review the status of all referrals to determine the number of days to initiate and complete investigations and work with staff to identify any impediments. In doing so, we recommended that it should develop a strategy to address all identified impediments to ensure that it reduces the number of days for initiating and completing all investigations to comply with required time frames. Further, we recommended that it should track the timeliness of support services, including whether youth have or have not received needed services, and it should ensure that its contracts include timeliness metrics.

Agency Comments

The department agreed with our recommendations and indicated that it will implement them.

Introduction

Background

State law affords youth1 who are placed in the foster care system various rights. Among such rights are the right to live in a safe, healthy, and comfortable home where they are treated with respect; the right to be free from physical, sexual, emotional, or other abuse; and the right to be free from corporal punishment and exploitation. To further the intent that all children are safe and free from abuse and neglect, state law mandated the creation of a public system of statewide child welfare services through CDSS and county welfare departments. Specifically, CDSS is responsible for providing oversight and guidance to counties. Counties are responsible for investigating reports of neglect and abuse, and taking steps to protect youth, including removing youth from their homes and placing them in the foster care system. In Alameda County, which is home to about 330,000 youth, its Social Services Agency is responsible for administering public social services in providing aid and services to families with dependent youth in Alameda County. As of July 2024, approximately 700 of those youth were in foster care.2

California Department of Social Services

State law requires CDSS to review child welfare services throughout the State. CDSS develops and oversees programs and services for at‑risk youth and families, as the text box shows, and it provides detailed guidance that counties must use to make decisions regarding child welfare services. One element of CDSS’s guidance is its provision to county welfare departments of Structured Decision Making (SDM) tools for screening reports of alleged child abuse and neglect and evaluating the safety risks for alleged victims who are the subjects of such reports.

California’s Child Welfare Services Include Programs and Services Intended to Do

the Following:

- Prevent abuse or strengthen families.

- Remedy the effects of abuse and neglect, through emergency response and family maintenance and family reunification.

- Provide for the out‑of‑home care of children, such as foster care and relative home placements.

- Provide for the permanent removal of children from abusive homes, through adoptions, legal guardianship, and kinship care.

Source: CDSS.

In 1989, state law authorized the development of the child welfare services case management system (CWS/CMS), which now links the State’s 58 counties and CDSS to a common online database that tracks each case from initial contact through termination of services. Counties and the State use CWS/CMS for all case management, service planning, and information gathering functions of child welfare services.

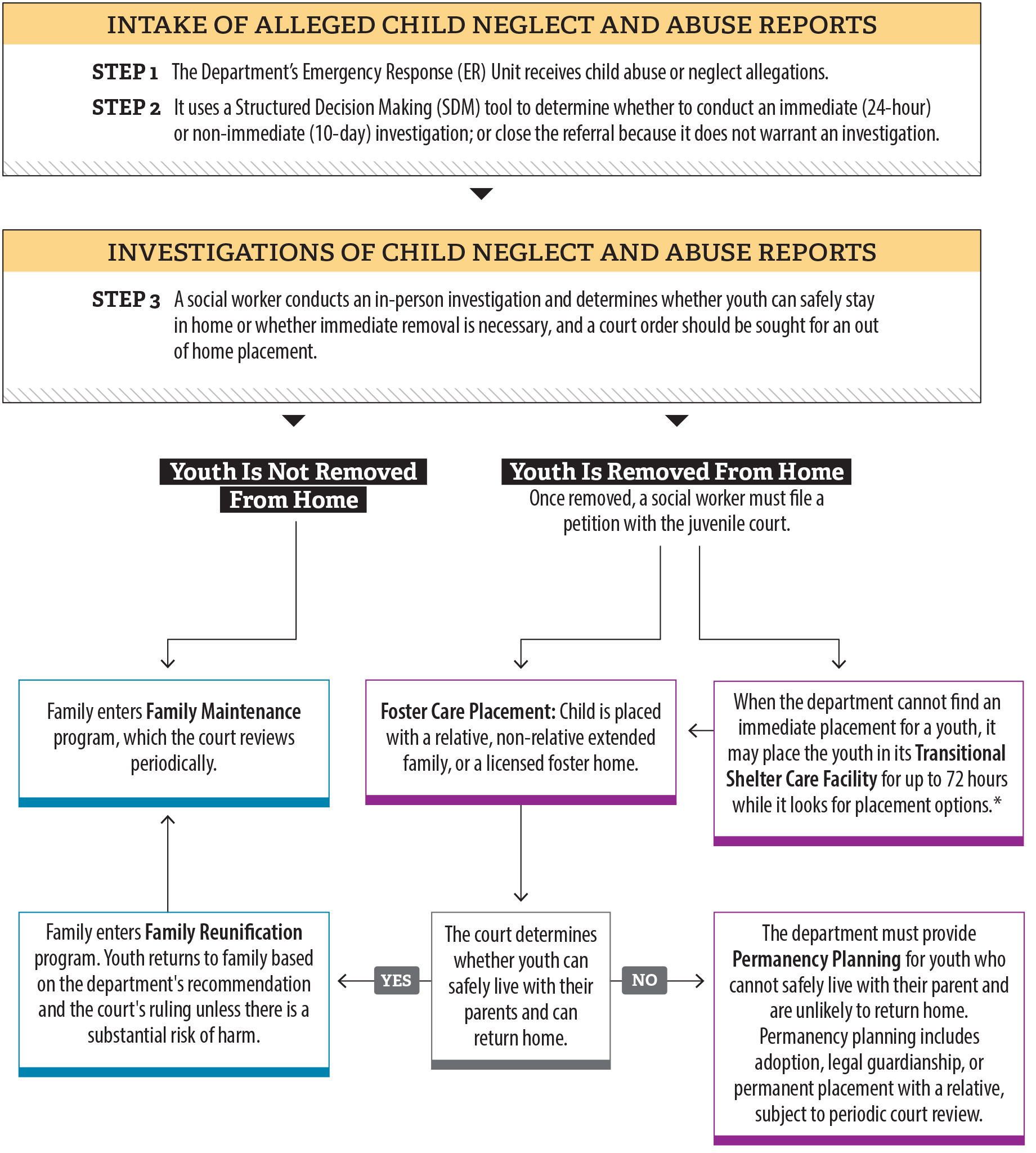

Alameda County Department of Children and Family Services

The Department of Children and Family Services (department) within the Alameda County Social Services Agency organizes and operates its own programs for child welfare services. With the direction of state law, the department is responsible for responding to reports of alleged child abuse and neglect and providing needed services to youth in the foster care system. To fulfill these responsibilities, the department determines whether a youth can safely remain in the home or should be removed from the home and which of the department’s several programs—such as family maintenance, family reunification, or permanency planning, as Figure 1 shows—will best support the youth.

Figure 1

The Department’s Approach to Determining Whether a Youth Can Safely Remain at Home or Should Be Removed

Source: State law, CDSS’s Child Welfare Services Manual, and the department’s Juvenile Dependency Flow Chart.

Note: The service components are simplified to show areas relevant to the audit subject. The department may have other services that are not represented in the graphic.

* Until July 2024, in cases where the department could not find an immediate suitable placement for youth, the department had the option to temporarily place youth in its transitional shelter. The department plans to reopen the shelter at a new location.

Figure 1 is a color-coded flow chart that describes the steps in receiving and investigating reports of alleged child neglect and abuse. The first box describes the two steps involved in intake of alleged child neglect and abuse reports. The next box indicates how the department investigates referrals. Next, the flow chart describes that when a youth is not removed from the home, the family enters a family maintenance program, which is reviewed every six months. The flow chart also shows that when a youth is removed from the home, the youth can be placed with a foster family or in a transitional shelter care facility for up to 72 hours, if immediate placement is not found. The court then determines if youth can safely live with their parents and return home. If so, the family enters Family Reunification program and then enters family maintenance, which the court reviews periodically. Otherwise, the department must provide Permanency Planning, which includes adoption, legal guardianship, or permanent placement with a relative, subject to periodic court review.

State law requires the department to provide family maintenance services to families whose children have become dependents of the court because of neglect, abuse, or other circumstances that create a substantial risk that the child may suffer serious physical harm or illness. The department provides family maintenance services, such as parenting courses in handling anger or child development, therapies, and other services to help maintain youth safely in their homes. If a child welfare worker decides to separate youth from their parents because of abuse and neglect, the department provides family reunification services with the purpose of reuniting youth with their parents. For youth who cannot safely live with their parents and are not likely to return to their homes, the department arranges permanency planning, allowing child welfare workers to seek adoption for the youth and terminate reunification services.

Reports of Alleged Child Abuse and Neglect

From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, the department received nearly 57,000 reports of alleged child abuse and neglect. State law requires the department to operate a 24‑hour emergency response system to receive and respond to reports of alleged child abuse and neglect. When individuals suspect child abuse or neglect, they can report it directly to the department through its 24‑hour emergency hotline. Furthermore, state law mandates that individuals in certain professions or roles that frequently interact with youth—such as teachers, physicians, counselors, or athletic coaches, and those who are referred to as mandated reporters—report all suspected child abuse and neglect. Examples of child abuse and neglect allegations include willfully harming or injuring a child, general neglect, sexual assault, or other allegations that the text box describes. After the department receives a report of an allegation, an intake worker may open a referral for either an immediate or non‑immediate investigation or may close it if the report does not warrant an investigation.

Child Abuse and Neglect Allegations Reportable to the Department Include:

Willfully Harming or Injuring a Child or Endangering the Health of a Child: When any person willfully causes or permits any child to suffer, or inflict thereon, unjustifiable physical pain or mental suffering or when a person with the custody of a child willfully causes or permits the health of a child to be endangered.

Unlawful Corporal Punishment: When any person willfully inflicts upon any child cruel or inhumane corporal punishment or injury resulting in a traumatic condition.

Sexual Abuse: Sexual assault and sexual exploitation.

Severe Neglect: Failure of a caretaker to protect a child from severe malnutrition or medically diagnosed nonorganic failure to thrive, or willfully placing the child’s health or safety at risk by intentional failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, or medical care. General Neglect: Failure of a person with custody of a child to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, or medical care or supervision where the child is at risk of suffering serious physical harm or illness.

Source: State Law.

Referrals and Investigations

There are three different outcomes a referral to investigate child abuse or neglect can produce, as the text box shows. When referrals indicate that youth are in imminent danger, the department must conduct an immediate in‑person investigation within 24 hours. If an allegation could constitute abuse or neglect but the youth is not at imminent risk, state law requires an in‑person response within 10 calendar days. For context, in each of the last six years, fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25, the department received reports of between 1,000 and 1,700 child abuse and neglect allegations that required immediate investigation, and it received between 1,500 and 2,100 for non‑immediate investigation. During an investigation, a child welfare worker interviews the youth and other parties involved in referrals to determine what actions, if any, are necessary to protect the youth from further abuse. When investigations substantiate the allegation, meaning the investigation determines that the alleged abuse or neglect more likely than not occurred, the department uses CDSS‑prescribed SDM tools3 to determine the next steps, including whether the youth can remain safely at home or should be removed from the home.

Possible Outcomes of Referrals of Child Abuse and Neglect

Unfounded investigation: The department’s investigation determines that the alleged abuse or neglect was false, was inherently improbable, involved an accidental injury, or did not constitute child abuse or neglect.

Inconclusive or unsubstantiated investigation: Because of a lack of sufficient evidence, the department could not determine whether the allegations of abuse or neglect occurred.

Substantiated investigation: The department’s investigation determines that the alleged abuse or neglect more likely than not occurred.

Source: State law and CDSS Child Welfare Services Program Requirements.

Structured Decision Making

The department assesses a youth’s immediate safety and the risk of future maltreatment using SDM tools. The SDM tools aid child welfare workers in determining the response priority required for reported incidents of child abuse and neglect. For example, the SDM tools help intake workers determine whether an in‑person investigation is warranted by answering specific questions the tools ask about the type of allegation, location of allegation, and historical information about the alleged victim and perpetrator. After a child welfare worker initiates an investigation, the SDM tools also assist the worker in making safety assessments to measure the presence of immediate safety threats in the home and risk assessments to determine the likelihood of future maltreatment and future child welfare system involvement.

Youth Placement Decisions

Before taking a youth into its custody, state law requires the department to consider whether a youth may remain safely in the home. If the department finds that taking the youth into custody is necessary for the youth’s health and safety, and the youth is not released to a parent or guardian, the department must petition a juvenile court to declare the youth a dependent of the court, and the court must hold a detention hearing no later than the end of the next court day after the department files the petition. If the court finds that removal of the youth from the custody of parents is necessary, the court must make a determination regarding the youth’s placement. The department plays a role in this decision, assisting the court in locating and providing the court with placement options, and state law grants youth the right to be placed with a relative or non‑relative extended family member, if an appropriate and willing individual is available.

Until July 2024, in cases where the department could not make an immediate suitable placement for youth, the department had the option to temporarily place youth in its transitional shelter, which CDSS had licensed Alameda County to operate and maintain. The shelter was staffed and managed by WestCoast Children’s Clinic (WCCC), a nonprofit children’s psychology clinic contracted with Alameda County, and the department was responsible to oversee the transitional shelter. The transitional shelter was intended to serve as a child‑friendly environment where youth in the child welfare services system could wait for a more appropriate placement, and it was permitted to hold youth for up to 72 hours before the department could make placement arrangements. The department was required to report to CDSS any instances of youth staying longer than 72 hours. The license terms and agreement for the transitional shelter required the department to provide youth with an individualized assessment of their placement, such as looking for potential relatives for placement options, and for service needs, such as crisis intervention services or psychological screening. The department suspended all operations at the transitional shelter in July of 2024 for several reasons, including its license expiration and a complaint that was made by the city of Hayward in which it was located. As of 2025, the department’s Division Director for Resource Family Approval, Placement, and ILP Support Services stated that the department plans to reopen the shelter at a new location, with a capacity to place 10 youth. The opening date of the new transitional shelter has not yet been determined because the department is waiting for the appropriate building permits.

The Department Has Faced Scrutiny in Recent Years

An Alameda County grand jury report for fiscal year 2022–23 identified shortcomings in the department’s ability to conduct timely investigations. Specifically, it found that in 2022, the department initiated less than half of non‑immediate investigations within the prescribed 10 days following the referral. The grand jury concluded that this recent decrease in investigations that happened within the 10‑day requirement was primarily the result of a 36 percent vacancy rate of child welfare workers in the department’s ER Unit—which handles investigations of child abuse and neglect reports—a shortage driven by the COVID‑19 pandemic. The report acknowledged the efforts the department had made at the time to address the critical staff shortage in the ER Unit but concluded that none had yet provided significant relief. As a result, the grand jury recommended that the department continue its efforts and consider additional extraordinary efforts to recruit and retain child welfare workers.

A 2024 review by CDSS also identified department shortcomings in the areas of identifying timely placements for youth, particularly those with complex needs; lack of documentation of placements, assessments, and services; and high job vacancy rates that create a barrier to family finding. CDSS reviewed case records and conducted a site visit, finding that the department demonstrated an inability to transition youth with the most complex needs to a suitable placement within the required 3‑day time frame. It also found a lack of evidence of children receiving services or support, such as specialty mental health services. CDSS recommended that the department develop policies and procedures that ensure the documentation of placement episodes,4 engagement with preventative services, and engagement with other departments to ensure high quality collaborative case planning. CDSS points to requirements in All County Letters5 and in state law as guidelines for crafting those policies and procedures.

Finally, in June of 2023, the city of Hayward filed a lawsuit against Alameda County and other defendants alleging that the conditions at the transitional shelter constituted a public nuisance and that the county failed to act in the best interest of youth in its care. In particular, the complaint alleged that minors faced the prospect of assault and sexual exploitation, including alleged human trafficking, at the hands of other youth at the shelter, and that daily calls for service to investigate youth who left the shelter without permission or who were engaged in criminal conduct burdened limited local police resources. Hayward filed a notice of settlement in September 2024, and the case was subsequently dismissed.

Audit Results

- High Job Vacancy Rates and Caseloads Have Contributed to Delays in Investigations of Alleged Child Abuse and Neglect

- The Department Has Not Ensured That Interagency Partners Provide Timely Services, Risking the Health and Safety of Foster Youth

- The Department’s Efforts to Connect Youth With Family and Keep Them Safe in Temporary Shelter Have Been Inadequate

High Job Vacancy Rates and Caseloads Have Contributed to Delays in Investigations of Alleged Child Abuse and Neglect

Key Points

- From July 2019 through March 2025, the Alameda County Department of Children and Family Services (department) did not consistently initiate or complete investigations within the required time frames, leaving children in potentially unsafe situations. Although circumstances beyond the department’s control contributed to its late initiation of the investigations we selected for review, its case files did not always contain adequate information describing why investigations were completed late, once started.

- Since July 2019, vacancy rates for child welfare workers have doubled and have more than doubled for child welfare supervisors. Although the department has taken some steps to address its vacancies, it could undertake additional efforts, such as recruiting more entry level staff and addressing some of the concerns of current staff to increase retention.

The Department Has Not Timely Initiated or Completed Investigations of All Referrals for Child Abuse and Neglect Allegations It Received

State law requires the department to operate a 24‑hour emergency hotline to receive and respond to reports of alleged child abuse and neglect. When the department receives such reports, it uses a tool prescribed by the California Department of Social Services (CDSS) to evaluate whether the nature of the allegation requires an in‑person investigation or whether the department can close the referral without further action. The department may close a referral without further action for several reasons, including when a report involves duplicate referrals that contain no new information or when the youth resides in another county. For all other referrals, the department must conduct in‑person investigations, as the text box shows. If the referral indicates that youth are in imminent danger of physical pain, injury, disability, severe emotional harm, or death, the department must conduct an in‑person investigation within 24 hours of receiving the referral (immediate referral). When an allegation could constitute abuse or neglect, but the child is not at imminent risk, state law requires an in‑person investigation within 10 days (non‑immediate referral).

The Department Must Perform Investigations Within Prescribed Time Frames:

Immediate Risk of Abuse, Neglect, or Exploitation: Requires an in‑person investigation within 24 hours. The department must complete the investigation within 30 days of the date of first in‑person contact.

Non‑immediate Risk: Requires an in‑person investigation within 10 days when a child is not in imminent danger, but there is a risk for their safety if the situation is not stabilized at home. The department must complete the investigation within 30 days of the date of first in‑person contact.

Source: Review of state law and CDSS policies.

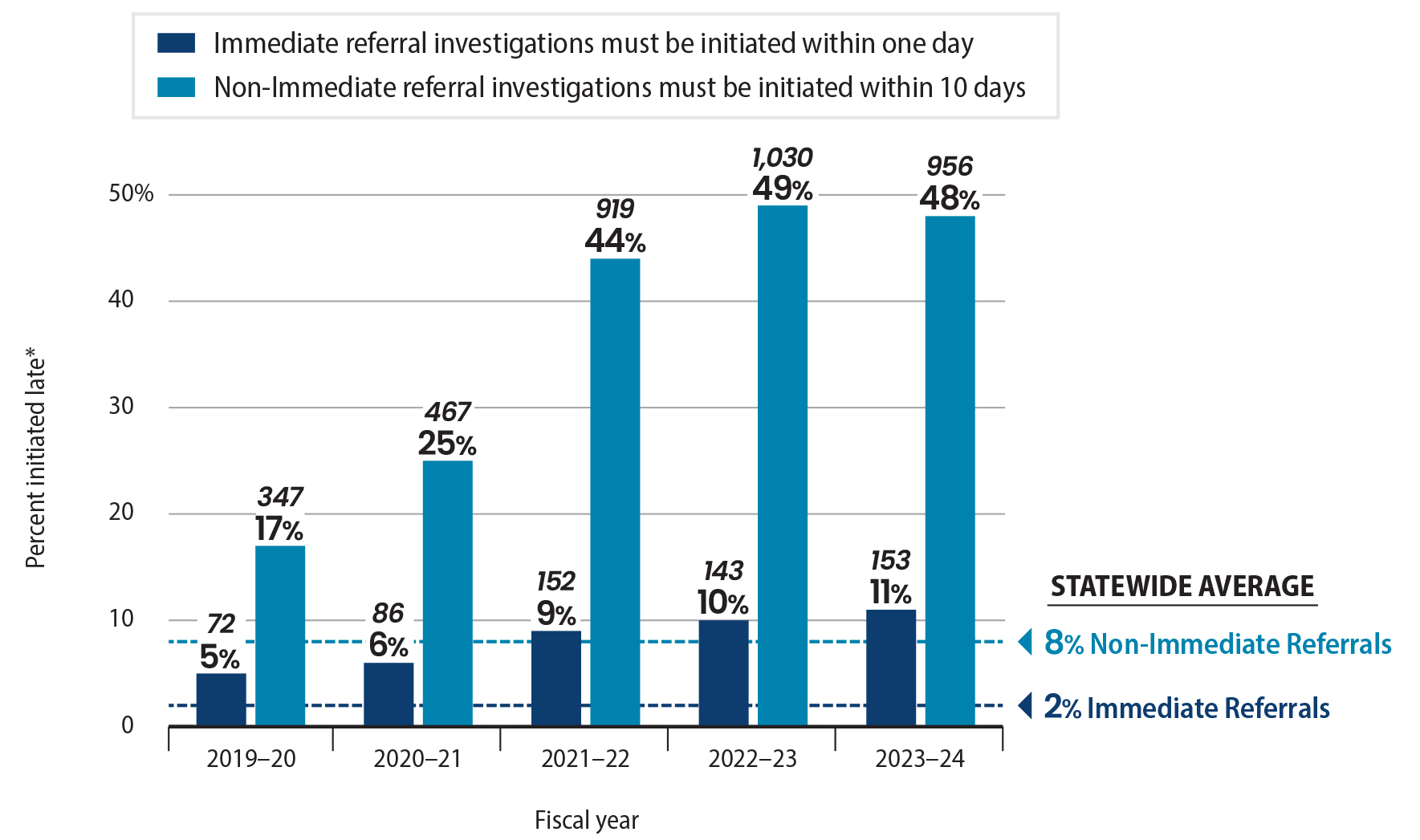

Delayed Initiation of Investigations

According to the department’s investigations data, the number of immediate and non‑immediate referrals for which it did not initiate investigations within the required time frames more than doubled from fiscal year 2019–20 through fiscal year 2023–24—the most recent fiscal year for which the department could provide complete data.6 Specifically, as Figure 2 shows, the percentage of investigations of immediate referrals that the department initiated after the prescribed 24‑hour time frame increased from 5 percent in fiscal year 2019–20 to 11 percent in fiscal year 2023–24. Similarly, the percentage of non‑immediate referrals for which the department initiated investigations after the prescribed 10‑day period increased from 17 percent in fiscal year 2019–20 to 48 percent in fiscal year 2023–24. Further, these percentages fall far short of statewide averages for the initiation of investigations. According to data published by the University of California, Berkeley and CDSS, the statewide averages for late initiation of investigations of immediate and non‑immediate referrals during this same period were just 2 percent and 8 percent, respectively. We present in Appendix A more detailed information on all referrals, including those that the department had not yet initiated, that the department received for the period we reviewed.

Figure 2

The Department Did Not Initiate Investigations for a Significant Percent of Referrals Within the Prescribed Time Frames

Source: Analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

Note: Although state law requires county welfare departments to respond to any report of imminent danger to a child immediately—or within 24 hours—the CWS/CMS data does not always include time data along with the recorded dates, therefore, our analysis determines immediate referrals to be on time if they were initiated within one day of receiving the referral.

* In addition to the investigations it initiated late, Alameda County had not initiated investigations for between 3 to 6 percent of immediate referrals, and 5 to 16 percent of non‑immediate referrals, it received during the years we reviewed. Appendix A provides a detailed breakdown by year.

Figure 2 is a bar chart that shows that the department did not initiate investigations for a significant percent of referrals within prescribed time frames. The figure shows that in fiscal year 2019-20 the department initiated investigations for 5 percent, or 72 immediate referrals after the required 24-hour time frame. The percentage of late initiation of investigations of immediate referrals increased to 11 percent, or 153 immediate referrals, in fiscal year 2023-24. Similarly, in fiscal year 2019-20, the department did not initiate investigations of non-immediate referrals within the required 10 days for 17 percent, or 347 referrals, which rose to 48 percent, or 956 referrals, in fiscal year 2023-24. The statewide average for not initiating investigations within the required time frames are 2 percent for immediate referrals and 8 percent for non-immediate referrals. A footnote to the figure states that in addition to the investigations it initiated late, Alameda County had not initiated investigations for between 3 to 6 percent of immediate referrals, and 5 to 16 percent of non‑immediate referrals, it received during the years we reviewed. Appendix A provides a detailed breakdown by year. The figure notes that although state law requires county welfare departments to respond to any report of imminent danger to a child immediately—or within 24 hours—the CWS/CMS data does not always include time data along with the recorded dates, therefore, our analysis determines immediate referrals to be on time if they were initiated within one day of receiving the referral. The source of the Figure is analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

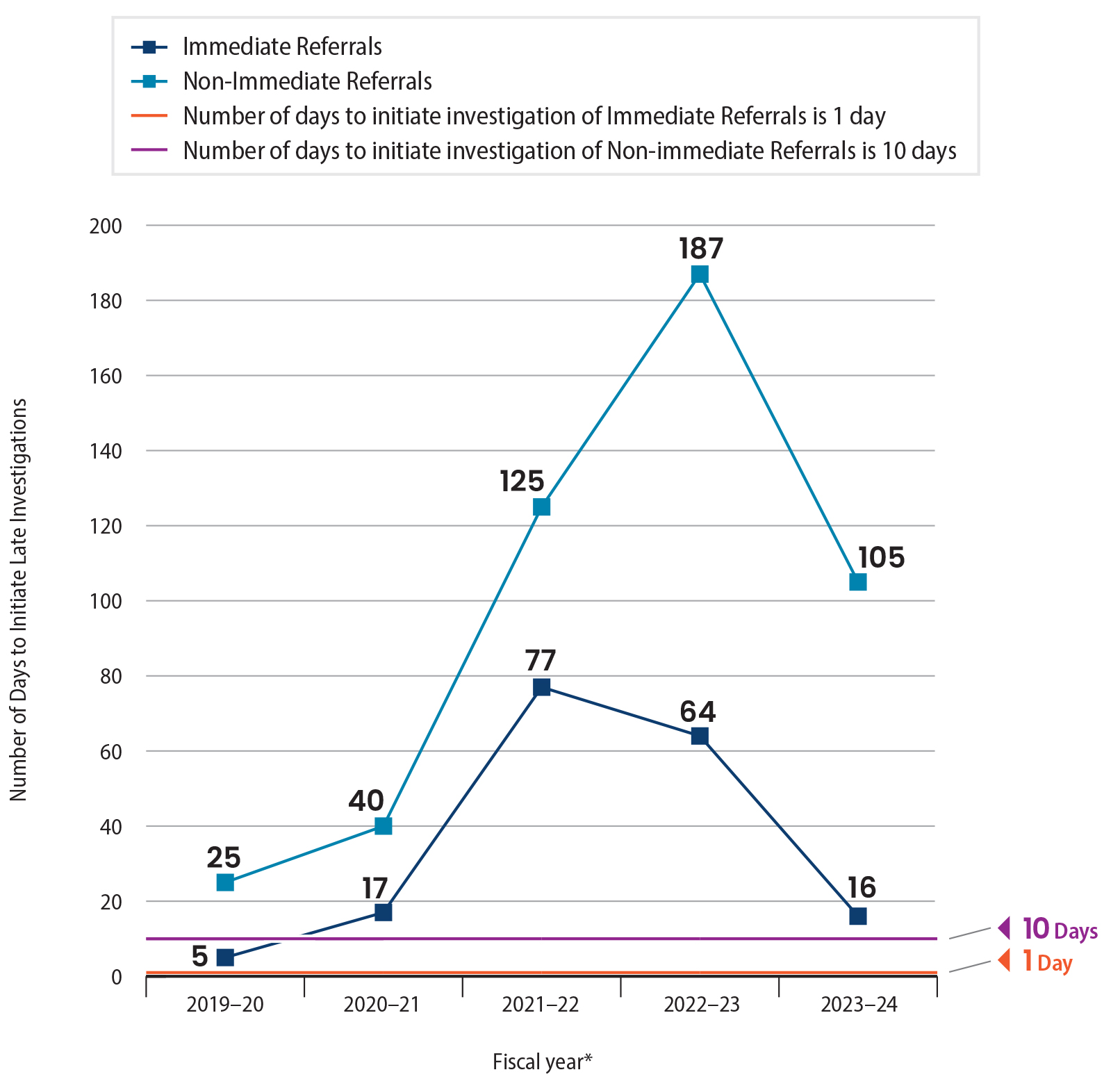

Moreover, for those investigations the department initiated after the prescribed time frames, it has generally taken longer on average to begin these investigations compared to fiscal year 2019–20, as Figure 3 shows. In fiscal year 2019–20, the average number of days to initiate late investigations was five days for immediate referrals and 25 days for non‑immediate referrals. The average number of days of late initiations of investigations for immediate referrals peaked at 77 days in fiscal year 2021–22 and 187 days for non‑immediate referrals in fiscal year 2022–23. Although these averages improved in fiscal year 2023–24 for those cases it closed by April 2024, the department still took an average of 16 days to initiate late investigations for immediate referrals and 105 days for non‑immediate referrals. The department’s inability to initiate investigations within the required time frames threatens the health and safety of the youth residing in Alameda County.

Figure 3

Although Average Days of Late Initiation of Investigations Improved in Recent Years, They Are Still Substantially Higher Than the Required Time Frames

Source: Alameda County’s CWS/CMS Data.

Note: In addition to the investigations it initiated late, Alameda County had not initiated investigations for between 3 to 6 percent of immediate referrals, and 5 to 16 percent of non‑immediate referrals it received during the years we reviewed. Appendix A provides a detailed breakdown by year.

* The State of Emergency proclaimed for the State of California due to the COVID‑19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020, through February 28, 2023.

Figure 3 is a line chart that shows the number of days the department was late in initiating investigations. Immediate referrals must be initiated within one day, and non-immediate referrals must be initiated within 10 days. On average, in fiscal year 2019-20 the department initiated immediate referrals five days late, and non-immediate referrals 25 days late. The average number of days to initiate late investigations increased in fiscal year 2020-21, then again increased significantly in fiscal year 2021-22. In fiscal year 2022-23, the department’s late initiations were at their highest for the audit period—64 days late for immediate referrals and 187 days late for non-immediate. In fiscal year 2023-24, the department initiated immediate referrals 16 days late on average, and initiated non-immediate referrals 105 days late on average. This is much lower than the previous fiscal year but is still much higher than the required time frame. The State of Emergency proclaimed for the state of California due to the COVID-19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020 through February 28, 2023. The Figure notes that in addition to the investigations it initiated late, Alameda County had not initiated investigations for between 3 to 6 percent of immediate referrals, and 5 to 16 percent of non-immediate referrals it received during the years we reviewed. Appendix A provides a detailed breakdown by year. The source of the Figure is analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

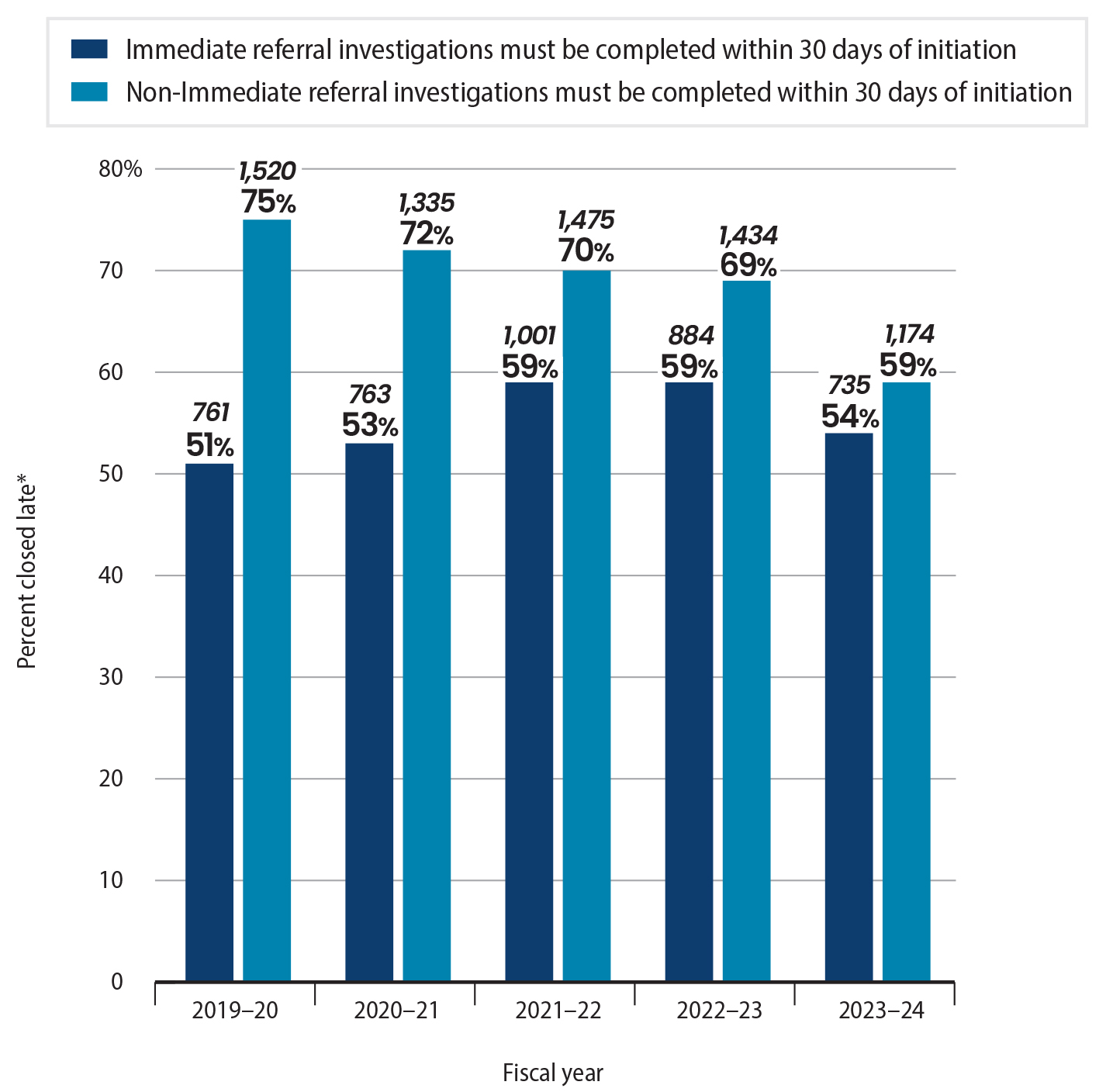

Late Completion of Investigations

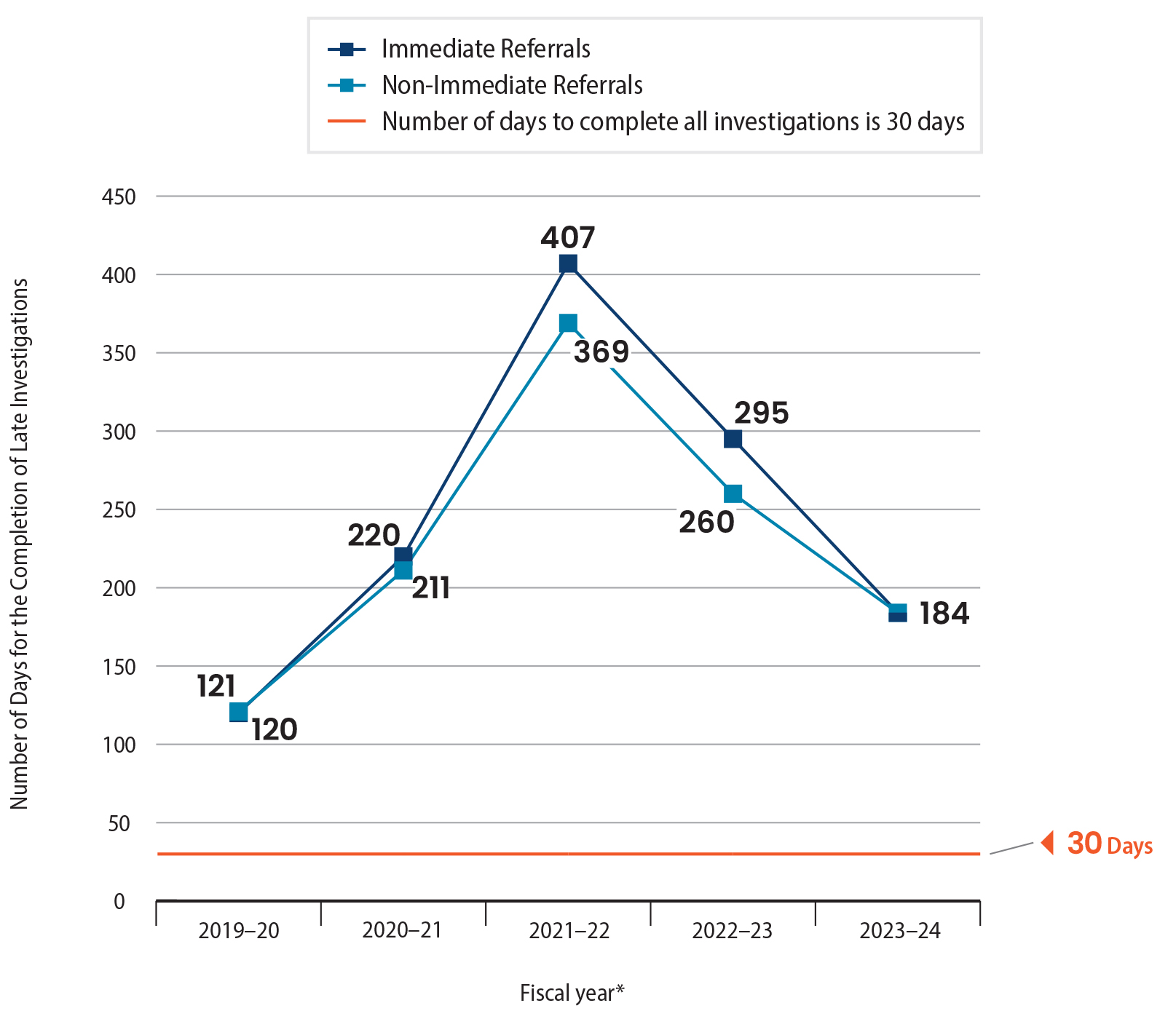

We also found that after initiating investigations, the department did not always complete them within the required time frames. CDSS requires counties to close an investigation within 30 days of the date that the child welfare worker performs an in‑person investigation with the youth. However, the department did not close investigations within 30 days for more than half of all immediate referrals from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, as Figure 4 shows. Although the percentage of investigations the department closed late for non‑immediate referrals decreased since fiscal year 2019–20, it still completed 59 percent of its investigations of non‑immediate referrals late in fiscal year 2023–24. Further, as Figure 5 shows, the average number of days to complete late investigations has increased compared to the average for fiscal year 2019–20. Unfortunately, there is no data available regarding the statewide averages for completing investigations. Appendix A provides more details regarding the department’s initiation and completion of investigations within prescribed time frames.

Figure 4

The Department Did Not Close Investigations for a Significant Percent of Referrals Within the Prescribed Time Frames

Source: Analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

* In addition to the investigations it closed late, Alameda County still had open investigations for up to 7 percent of the immediate and non‑immediate referrals it received during this period. Appendix A provides a detailed breakdown by year.

Figure 4 is a bar chart showing that the department did not close investigations for a significant percent of referrals within the prescribed time frame. The department must close investigations of alleged neglect and abuse within 30 days of initiation. From fiscal years 2019-20 through 2023-24, the department closed about half of its immediate investigations late—51 percent in fiscal year 2019-20, 53 percent in fiscal year 2021, 59 percent in fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23, and 54 percent in fiscal year 2023-24. The department closed 75 percent of its non-immediate investigations late in fiscal year 2019-20, declining each year. The department closed 59 percent of its non-immediate investigations late in fiscal year 2023-24. In addition to the investigations it closed late, Alameda County still had open investigations for up to 7 percent of the immediate and non-immediate referrals it received during this period. Appendix A provides more detailed breakdowns by year. The source of the Figure is analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

Figure 5

Although the Average Days for the Completion of Late Investigations Improved in Recent Years, They Are Still Substantially Higher Than the Required Time Frame

Source: Alameda County’s CWS/CMS Data.

Note: In addition to the investigations it closed late, Alameda County still had open investigations for up to 7 percent of the immediate and non‑immediate referrals it received. Appendix A provides a more detailed breakdown by year.

* The State of Emergency proclaimed for the State of California due to the COVID‑19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020, through February 28, 2023.

Figure 5 is a line chart showing the average number of days the department completed investigations late per fiscal year. The department must complete all investigations within 30 days. It shows that in fiscal year 2019-20, the department completed investigations 120 days late for immediate referrals and 121 days late for non-immediate referrals. The average number of days rose sharply in fiscal year 2021-22, to 407 days late for immediate referrals and 369 days late for non-immediate referrals. In fiscal year 2023-24, the number of days late reduced to 184 for both immediate and non-immediate referrals. It also shows that the State of Emergency proclaimed for the State of California due to the COVID-19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020, through February 28, 2023. The Figure notes that in addition to the investigations it closed late, Alameda County still had open investigations for up to 7 percent of the immediate and non-immediate referrals it received. Appendix A provides more detailed breakdowns by year. The source of the Figure is analysis of Alameda County’s CWS/CMS data.

Reasons for Delays in Cases We Reviewed

To assess the reasons for the delays in the department’s initiation and completion of investigations, we reviewed a selection of investigations of 10 immediate referrals and 10 non‑immediate referrals—for a total of 20 referrals. We reviewed case file documents, case worker notes, and interviewed staff to determine the cause of the delays and whether the department’s efforts were appropriate. We found that the department did not initiate an investigation for one of the 10 immediate referrals within 24 hours of receiving it, and did not initiate an in‑person investigation of four of the 10 non‑immediate referrals within the required 10 days, as the text box shows. Specifically, the department made an in‑person contact with the youth involved in the one immediate referral three days after receiving the allegation. For three of the four non‑immediate referrals, the department did not make in‑person contact with the involved youth until as many as 28 days after receiving the referral, and in the fourth instance, the department could not reach the family or the youth at all.

Timeliness of First In‑Person Contact for 20 Referrals We Reviewed

Late First In‑Person Contact: The department made first in‑person contact for one of 10 immediate referrals and four of 10 non‑immediate referrals after the required time frames.

Source: Review of investigation files.

In all five instances, the delays in initiating required investigations were because of circumstances beyond the department’s control. For example, according to notes in the case file for the one immediate referral for which the department did not initiate an in‑person investigation within 24 hours, the department staff attempted to meet with the youth at school on the same day that the department received the report of alleged abuse and neglect; however, the youth was not at school. The staff also called the parent of that youth on the same day and learned that the parent was also not available because of a personal appointment. Ultimately, the child welfare worker scheduled and met with the youth and the parent three days after receiving the referral.

The department faced similar circumstances for three of the four non‑immediate referrals for which it did not initiate an in‑person investigation within the required 10 days. For one of these referrals, the child welfare worker made a few attempts to contact the parent of the youth within 10 days, including leaving voice messages and visiting the home. The department staff was able to contact the parent on the telephone and schedule an in‑person meeting just before the 10‑day period expired. However, the parent was then unable to meet as scheduled because of health reasons, and the child welfare worker had to reschedule and meet with the parent 20 days after the department received the non‑immediate referral. Similarly, the child welfare worker attempted, but was unable, to contact the youth for two other non‑immediate referrals within 10 days of receiving the referrals, resulting in no in‑person contact for almost a month after receiving the referrals. We recognize the challenges the child welfare workers face in contacting the youth and families; however, delays in investigating allegations of child abuse and neglect risk the health and safety of the youth.

For the remaining one non‑immediate referral that the department did not close within the required time frame, despite repeated attempts, it could not contact the family or the youth at all. The referral notes show that the child welfare worker made four separate attempts to contact the youth and the family, including telephone calls, text messages, and a letter to the mother’s last known address. Ultimately, the child welfare worker noted that she was unable to locate the family and closed the referral. This was an appropriate action—according to CDSS policy, the child welfare worker may close the referral if attempts to locate the family are unsuccessful.

Further, as the text box shows, in 10 of the 20 investigations we reviewed, the department exceeded the time frame for closing investigations, which is 30 days from the first in‑person contact. For those 10 investigations, the department took from 42 to 476 days—with an average of 275 days—to conclude the investigations.

Timeliness of Completing 20 Investigations We Reviewed

Late Investigation Completion: The department closed investigations for four of 10 immediate referrals and six of 10 non‑immediate referrals after the 30‑day requirement.

Source: Review of investigation files.

Notes in the case files for seven of the 10 late investigations did not provide any details to determine the reasons for the late closure of investigations. For example, according to the case file notes, the department received a non‑immediate referral in December 2023, and the child welfare worker assigned to the case made the first in‑person contact within 10 days, as required. However, the child welfare worker did not complete the safety and risk assessment until November 2024. As such, the investigation did not close until nearly a year after the first in‑person contact. Nothing in the case file provided any information for the late assessment. The director of the Prevention and Intake Services Division stated that the child welfare worker did not complete the assessment in a timely manner, but could not provide any further explanation.

In the remaining three cases, the child welfare worker completed the investigation within 30 days and recommended closing the three referrals with no further agency involvement. However, the assigned supervisor did not review and approve the recommendations until after the 30‑day period had passed. The assistant agency director for Alameda County Social Services Agency (assistant agency director), who manages the department, confirmed that the department needs to close its investigations in a timely manner consistent with state law and CDSS requirements, which require supervisory signoff. She noted that staffing issues in the department created a situation in which the department could not keep up with referrals. As we describe in the next section, the department has been experiencing high staff and supervisor vacancy rates, including a 35 percent child welfare worker vacancy rate in fiscal year 2023–24. Department management cited these high vacancies and large caseloads as the reason for the delays in responding to and investigating referrals in a timely manner.

We also reviewed whether the department appropriately closed reports of alleged child neglect or abuse that it determined did not require further investigation. The department uses a tool prescribed by CDSS when determining whether to refer a report of neglect or abuse for further investigation. We selected 10 reports of alleged child neglect or abuse that the department closed without any in‑person investigation. The department appropriately closed five reports for which the CDSS‑prescribed tool recommended closing without an in‑person investigation. However, the department overrode the tool’s recommendation to conduct in‑person investigations for the remaining five reports of alleged neglect or abuse.

For four of the five reports for which the department chose to deviate from the tool’s recommendation, we found that it documented a reasonable explanation for doing so. For example, in one instance, although the tool’s recommendation was to refer the report for an in‑person investigation, it had received a duplicate allegation regarding the family one day earlier. As such, the department overrode the recommendation for the report we selected and closed it by combining the two reports of neglect or abuse. The department recommended an in‑person investigation of the allegations for the combined report.

Although the department had a valid reason for closing the remaining one report for which the department overrode the CDSS‑prescribed tool’s recommendation to perform an in‑person investigation, it unnecessarily delayed its investigation of the underlying allegations. Despite the CDSS‑prescribed tool’s recommended action to conduct an in‑person investigation, the department closed a report it received in April 2023 alleging parents’ negligence to follow up on a youth’s important medical appointments. The division director of the Prevention and Intake Services Division (division director) stated that at the time it received the report in April 2023, the child welfare worker assigned to the report went on leave, and as a result the department did not timely complete the intake of that report. The department noted in the investigation case file that it received a similar report involving the same family a month later, in May 2023. Case file notes stated that the department chose to combine the two reports and close the April report. The department recommended an in‑person investigation for the May 2023 report. By delaying the review of the April report until it received another report in May, the department potentially jeopardized the youth’s health and safety.

The Department Has Not Taken Sufficient Action to Address Its Increasing Staff Vacancy Rates and High Caseloads

To review foster child placements and investigate child abuse claims, state law requires that child welfare agencies maintain and operate a 24‑hour response system. The department hires child welfare workers and supervisors to provide intake services for child abuse and neglect allegations, to investigate child abuse and neglect referrals, and to provide placement and foster care services for youth who are determined to be dependents of the court.

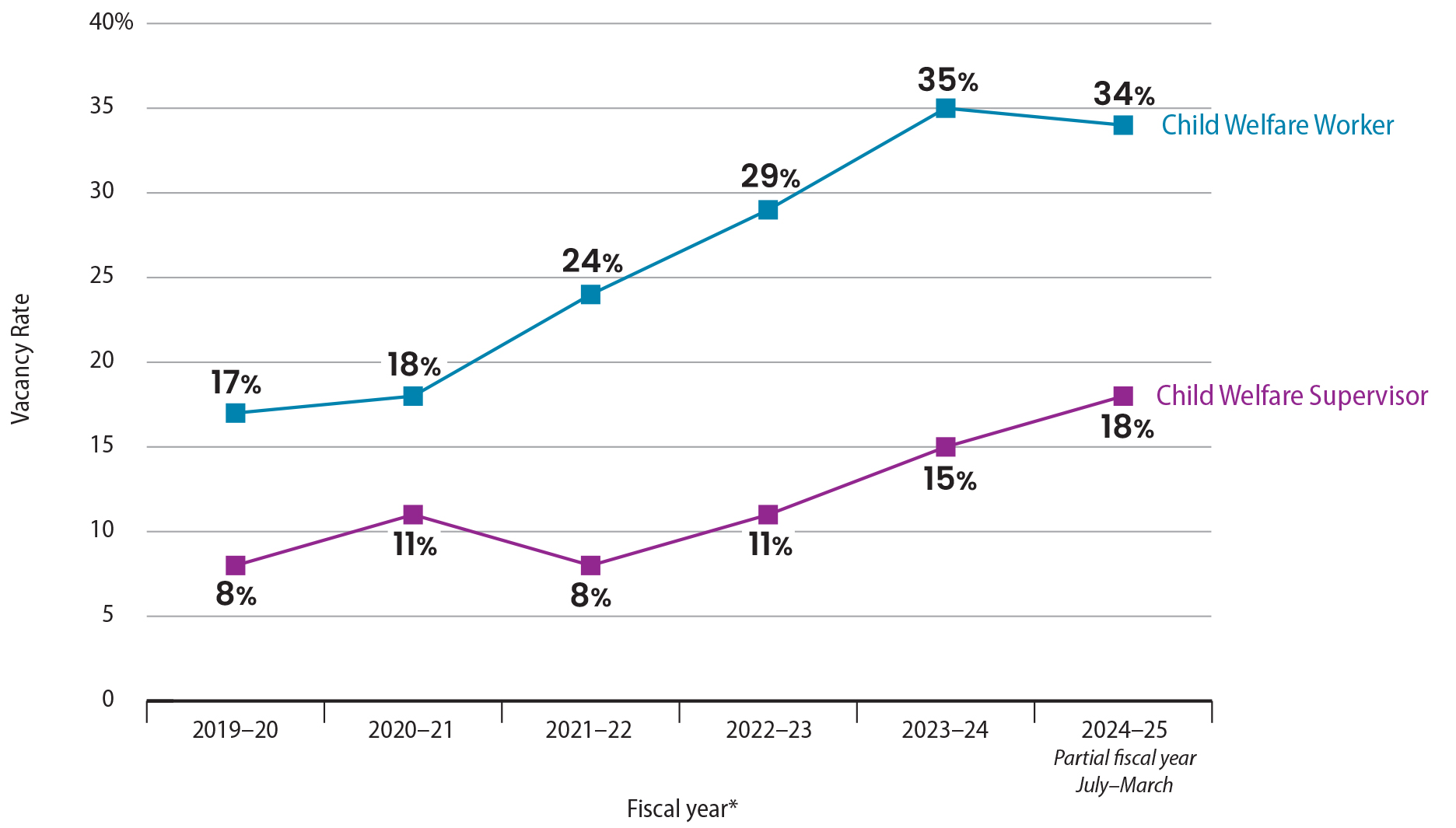

The department has experienced high vacancy rates for its child welfare workers and supervisors. The department’s vacancy rate for child welfare workers doubled from 17 percent in fiscal year 2019–20 to 34 percent in fiscal year 2024–25, as Figure 6 shows. Similarly, its vacancy rate for supervisors more than doubled from 8 percent in fiscal year 2019–20 to 18 percent in fiscal year 2024–25.

Figure 6

The Vacancy Rate of Child Welfare Workers and Child Welfare Supervisors Has Significantly Increased From Fiscal Years 2019–20 Through 2024–25

Source: Review of department position control documents.

Note: During all fiscal years shown, the department had 290 authorized positions for child welfare workers, and 77 for child welfare supervisors.

* The State of Emergency proclaimed for the State of California due to the COVID‑19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020, through February 28, 2023.

Figure 6 is a line chart showing the vacancy rate of child welfare workers and child welfare supervisors has significantly increased from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2024–25. In fiscal year 2019-20, the department had a vacancy rate of 17 percent for child welfare workers and 8 percent for child welfare supervisors. The vacancy rate for child welfare workers increased each year through fiscal year 2023-24, where it reached 35 percent. Partial year data for fiscal year 2024-25 shows a decrease of vacancy rates for child welfare workers to 34 percent. The footnote stated that fiscal year 2024-25 is based on data for July 2024 through March 2025. Child welfare supervisor vacancies rose to 11 percent in fiscal year 2020-21, fell to 8 percent in fiscal year 2021-22, then rose steadily to 15 percent in fiscal year 2023-24 and to 18 percent as of March 2025. A footnote states that the State of Emergency proclaimed for the State of California due to the COVID-19 pandemic was in effect from March 4, 2020, through February 28, 2023. The Figure notes that during all fiscal years shown, the department had 290 authorized positions for Child Welfare Workers, and 77 for Child Welfare Supervisors. The source of the Figure is a review of department position control documents.

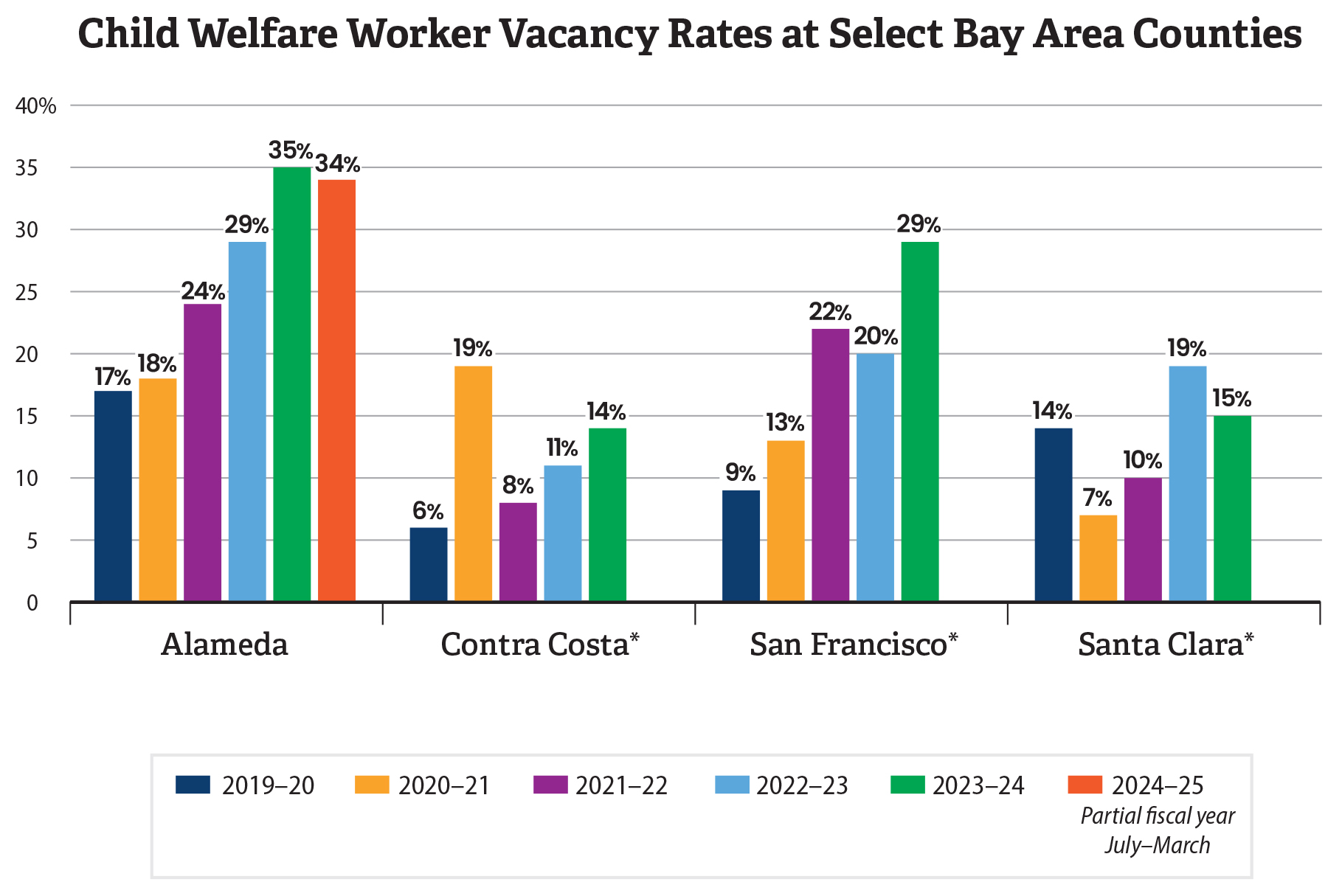

In fact, Alameda County has experienced a higher vacancy rate for child welfare workers compared to other nearby counties. To determine whether Alameda County’s vacancy rates were comparable to a selection of three counties also located in the Bay Area—Contra Costa, San Francisco, and Santa Clara—we asked CDSS to provide us with vacancy rates for child welfare worker positions for the other three counties from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24. We learned that Alameda County experienced an average vacancy rate in child welfare supervisors of 11 percent during the five‑year audit period, which was lower than Contra Costa’s 18 percent average vacancy rate and San Francisco’s 15 percent rate. However, as Figure 7 shows, Alameda County’s vacancy rate for child welfare workers was higher than the other three counties during the period we reviewed. The three counties reported that they had an average vacancy rate for child welfare workers below 20 percent during the five years we reviewed. However, Alameda County experienced an average of 25 percent for child welfare workers during this same period. San Francisco County, which had the second highest vacancy rates in recent years, reported its vacancy rates for child welfare workers at 29 percent for fiscal year 2023–24, which is still less than Alameda County’s 35 percent vacancy rate for its child welfare workers during the same year.

Figure 7

The Child Welfare Worker Vacancy Rates in Alameda County Have Been Consistently Higher Compared to Other Bay Area Counties

Source: Review of the department’s position control data and CDSS’s annual training surveys.

Note: For Alameda County, we used the department’s position control data. For all other counties, we obtained data from CDSS’s annual training surveys.

* CDSS did not yet have fiscal year 2024–25 data for Contra Costa, San Francisco, and Santa Clara counties.

Figure 7 is a bar chart showing that the child welfare worker vacancy rates in Alameda County have been consistently higher compared to other Bay Area counties. The Figure shows child welfare worker vacancy rates from fiscal years 2019-20 through 2023-24 and partial year (July to March) for fiscal year 2024-25 for Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, and Santa Clara counties. For each fiscal year, Alameda County’s vacancy rate is substantially higher than the nearby counties. In fiscal year 2019-20, vacancy rate for Alameda County was at 17 percent, Santa Clara at 14 percent, San Francisco at 9 percent, and Contra Costa County at 6 percent. Alameda County reached its highest vacancy rate in fiscal year 2023-24 at 35 percent; while the vacancy rate in the same fiscal year for Santa Clara County was 15 percent, San Francisco County was 29 percent, and Contra Costa was 14 percent. From June 2024 through March 2025, Alameda County had a 34 percent child welfare worker vacancy rate. A footnote states that CDSS did not yet have fiscal year 2024–25 data for Contra Costa, San Francisco, and Santa Clara counties. The Figure notes that for Alameda County, we used the department’s position control data. For all other counties we obtained data from CDSS’ annual training surveys. The source of the Figure is review of the department’s position control data and CDSS’s annual training surveys.

The assistant agency director attributed the department’s high vacancies to a nationwide shortage of child welfare workers and the nature of the work. She noted that the demand for social workers, particularly for child welfare workers, is growing faster than the supply of individuals willing to do the work. In fact, a study based on data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System confirms that public child welfare agencies face challenges, including high workforce turnover.7 Specifically, the study found that from 2003 through 2015, the median turnover rate for all states was from 14 percent to 22 percent and that case workers stayed on the job for a median of 1.8 years. The assistant agency director explained that the COVID‑19 pandemic resulted in challenges in recruitment and retention because of factors such as anxiety about conducting home visits and increased stress. She also noted that the intense and often traumatic nature of the work, with exposure to challenging situations involving youth and families, can lead to stress and burnout among child welfare workers.

The department’s child welfare workers we interviewed also identified stress as one of the biggest challenges leading to staff turnover. We spoke with four child welfare workers at the department to understand their perspectives on high vacancy rates. Staff identified department culture and lack of resources as some of the challenges, as the text box shows. Staff told us that because they often assist families experiencing extreme poverty, any inability to provide necessary resources or services to families due to unclear rationale for limits on what the department can provide to families puts undue stress on child welfare workers because they are the family’s primary contact with the department. They also told us that certain department policies place undue stress on them. For example, staff stated that department policy requires that they conduct in‑home, unannounced interviews for every family member, even if they were not directly involved in the cause for investigation, which often requires significant travel that can take up much of a workday. The staff offered some suggested changes to assist in lowering the high vacancy rates, including creating a new pay differential for daytime Emergency Response (ER) Unit workers because of the added safety concerns and intensity of the work, and not requiring in‑home, unannounced interviews for family members not directly involved in the incident being investigated.

Some of the Challenges Leading to Staff Turnover That Child Welfare Workers We Interviewed Identified Involved Problems With Department Culture and Resources:

- Upper management does not effectively communicate the reasons for certain policies, procedures, or priorities, leaving workers frustrated and in the dark.

- Upper management does not take child welfare workers’ concerns and ideas for improving the department seriously, nor do they offer many concrete avenues for workers to express those concerns or ideas, other than to their direct supervisor.

- Upper management does not understand the reality of the day‑to‑day work the job requires, especially when workers are going above and beyond to complete their work on time.

- Delays in payment processing for foster parents put undue stress on child welfare workers because they are a foster parent’s primary contact with the department.

Source: Interviews with selected child welfare workers.

In 2023, the department identified similar feedback through exit interviews with employees who resigned, as well as through a workforce survey. Specifically, the department found that emotional exhaustion, demands and expectations of the job, work culture, and insufficient resources to complete work, were some of the key reasons that employees would consider ending their employment or changing their positions. Nearly 60 percent of the respondents agreed that there is not clear and timely communication between management and frontline staff about department policy changes. Further, nearly 70 percent of the respondents agreed that work is not adequately distributed.

Moreover, in fiscal year 2022–23, a report by the Alameda County grand jury identified several factors that contributed to the department’s high vacancy rates, including a lack of supervisor support and mentoring. In particular, the report noted that some supervisors do not devote enough time and effort to support and mentor new staff in learning to manage caseloads and perform investigations. The report recommended that the department take steps to increase work‑related support for child welfare workers by requiring supervisors to schedule regular check‑ins and provide timely guidance and mentoring for caseload management, among other things. According to the assistant agency director, although the department has implemented the grand jury’s recommendations, the recommendations did not address the issue of not having a sufficient applicant pool for child welfare worker positions.

The assistant agency director does not believe that lack of funding or salaries have contributed to the department’s vacancies. She believes that the county’s salaries for its child welfare workers are competitive compared to similar positions in other Bay Area counties. Although she acknowledged that some staff are leaving for positions in other counties, she does not believe that pay is the only reason staff are leaving. She stated that staff are also leaving for positions in other Alameda County agencies where the pay is less, but the workload is more balanced. Our review of child welfare worker salaries in Contra Costa, Santa Clara, and San Francisco found that the department’s salaries were generally comparable with the other Bay Area counties, considering the cost of living. In fact, the employee feedback that the department compiled in 2023 found that employees cited pay and benefits as the key reason for maintaining their employment.

The high number of vacancies in Alameda County has resulted in higher caseloads for child welfare workers and has hindered the department’s ability to meet the needs of the county’s youth and families. The assistant agency director noted that the department’s high vacancy rates are increasing staff caseloads and causing an emotional burden on staff and managers who are responsible for assisting youth and families. In fact, a fiscal year 2022–23, Alameda County’s Grand Jury Final Report found that the department’s high vacancies led to additional stress and higher caseloads of emergency response child welfare workers at the department, which in turn resulted in delays in investigating the non‑immediate referrals for child abuse and neglect investigations.

In recent years, child welfare workers’ caseloads have exceeded agreed‑upon guidelines for the Emergency Response Program administered by its ER Unit, which is responsible for investigating reports of child neglect and abuse. As the text box shows, the union agreement with the county in 2015 set certain caseload guidelines for child welfare workers, depending on their classification.8 We obtained case assignment data from the department to assess its adherence to the caseload guidelines. Specifically, to assess caseloads for the Emergency Response Program, we identified the number of new emergency response cases the department assigned to each staff during each calendar month of our audit period. We aggregated the number of instances, or staff‑months, for which individual staff had new emergency response caseloads exceeding 15 cases. For example, if two staff each had a total new emergency response caseload of more than 15 during a month, we counted that as two staff-months with caseload exceeding the guidelines of 15 cases. As Table 1 shows, from fiscal years 2019–20 through 2023–24, the department consistently assigned new monthly emergency response caseloads to staff that exceeded the caseload guidelines, with 15 to 30 percent of all staff‑months exceeding the guidelines each year. In contrast, as Appendix B shows, we found that the department generally met the caseload guidelines when assigning cases for the family maintenance and family reunification programs.

The Union Agreement With Alameda County Set Certain Caseload Guidelines for Child Welfare Workers

Emergency Response Program: No more than 15 new cases per month.

Family Maintenance Program: No more than 28 cases per day.

Family Reunification Program: No more than 19 cases per day.

Source: Alameda County’s agreements with the union executed in 2015.

The department has attempted some strategies to address its vacancies and related high caseloads. For example, in November 2022, it used involuntary staff transfers to help address open referrals and reduce caseloads in the ER Unit. According to the division director, the plan was to rotate seven staff from other units to the ER Unit for one year after which they could return to their previous roles in their former units. However, she noted that most staff either resigned or went out on leave before the end of the year. Ultimately, she believed that the strategy did not provide much progress in addressing referrals, and it severely harmed staff morale. In addition, the department explained that in 2023, it implemented another rotational program to help address the backlog of referrals created when staff left the department. This rotation program included transferring six staff on a three‑month rotation to the ER Unit to focus on existing open referrals. The division director explained that the program ended in fall 2024 when the department had addressed the backlog of referrals for the workers who had left.

Although the department has expanded its recruitment of the Child Welfare Worker I (CWW I) position in recent years, it is still able to hire more staff at this entry level position, which may be easier to recruit. In 2023, the department expanded its recruitment beyond the Child Welfare Worker II (CWW II) position, which requires a master’s degree, to include the CWW I position, which requires only a bachelor’s degree with two years of experience in specific areas. The first cohort of individuals hired into the CWW I position joined the department in September 2023 with a total of 15 new staff, of which it assigned nine to the dependency investigation and family maintenance programs of the ER Unit. As of July 2025, the department had 32 child welfare workers in the CWW I position, with 26 of them assigned to the ER Unit—this number comprises about 29 percent of all child welfare workers in the division. The state requirement for an emergency response program is that at least 50 percent of workers should have a master’s degree, and the other 50 percent may have only a bachelor’s degree. To reduce the existing vacancy gap in its ER Unit, we believe that the department can hire more individuals in the CWW I position, which has less educational requirements and may be easier to recruit. The assistant agency director noted that entry level child welfare workers require more direct oversight and involvement by supervisors. For this reason, she noted that it is preferable to hire more experienced individuals into the CWW II position. However, we believe that the department could implement a practice in which new child welfare workers can shadow more experienced staff and reduce the time supervisors need to spend with the new staff. This approach could thereby allow the department to hire more staff at one time. Even though the department says that it has tried voluntary shadowing in the past, we believe that it could formalize the shadowing process and make it mandatory for new staff.

The Department Has Not Ensured That Interagency Partners Provide Timely Services, Risking the Health and Safety of Foster Youth

Key Points

- The department has not ensured that youth in foster care (foster youth) receive needed services in a timely manner because it has not consistently documented and tracked the frequency and the timeliness of services provided by its interagency partners or the department’s contractors. We reviewed 125 selected services that 36 youth needed to receive and found that the department did not document when 65 services were requested or delivered—preventing us from determining whether the youth received those services in a timely manner. Case files lacked documentation to determine the timeliness of services involving 89 percent of regional center services and more than 90 percent of mental health services.

- In cases for which sufficient documentation was available for our review, we found that the department did not always ensure timely provision of services for some youth. Specifically, of the 60 selected services that had sufficient documentation, we found that youth received 27 of them only after delays. For example, the provision of sexual education classes had the longest average delay of 456 days.

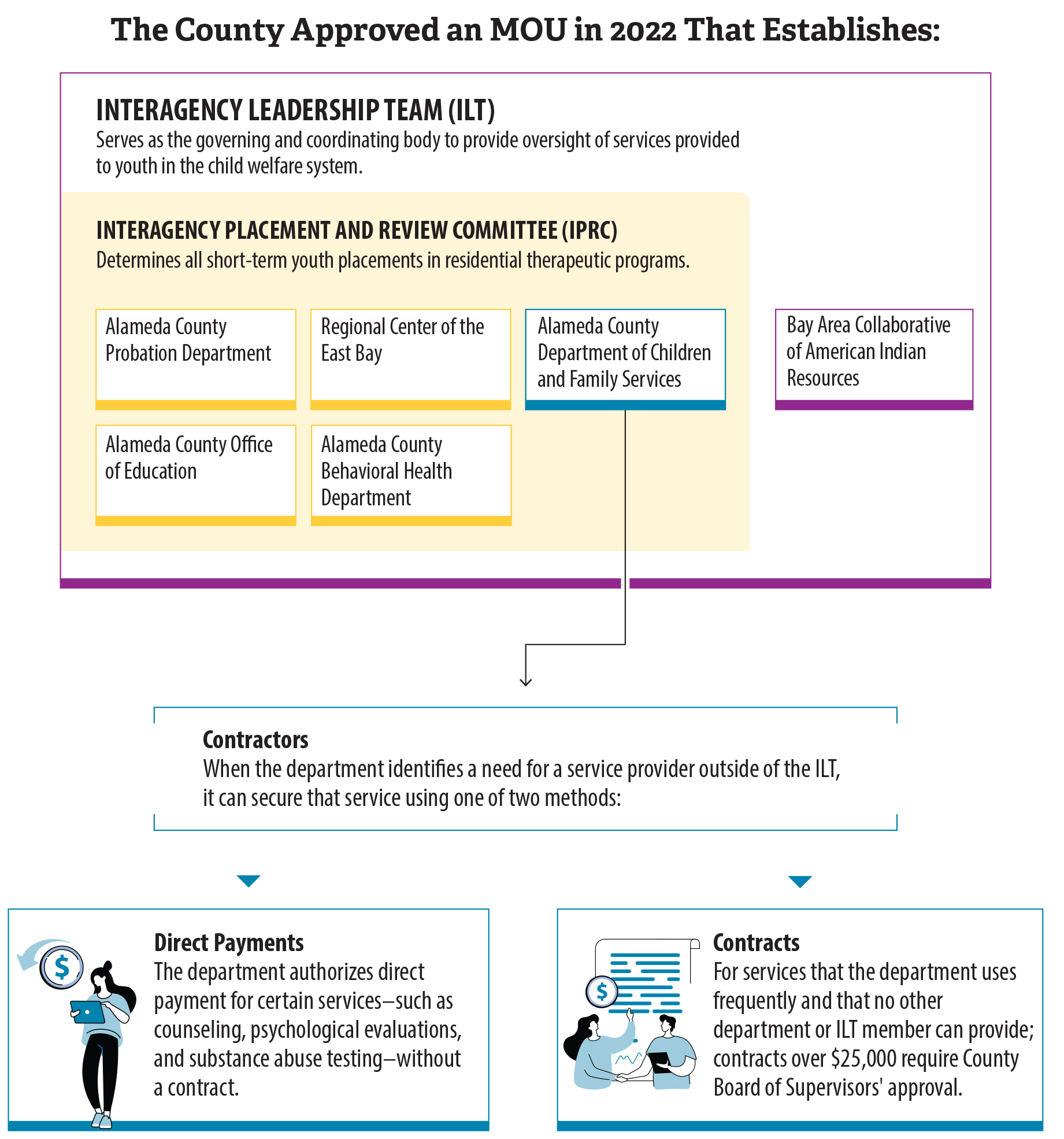

Lack of Documentation Prevents the Department From Demonstrating That Foster Youth Received Timely Services

State law requires that counties establish MOUs with certain public and private partners to collaborate on the delivery and management of services to foster youth. State law requires the county to establish the MOU to ensure that youth in foster care receive coordinated, timely, and trauma‑informed services. Alameda County established an MOU in May 2022, which includes the partners for its interagency leadership team (ILT), as Figure 8 shows. The department’s partners on the MOU are the Alameda County Behavioral Health Department, the Alameda County Office of Education, the Regional Center of the East Bay, and the Alameda County Probation Department. These interagency partners provide foster youth with certain services, such as education case management services; services for youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities; and the coordination of referrals, screening, eligibility, and authorization for therapeutic care for youth with complex emotional and behavioral needs. For services that the department regularly requires and that its interagency partners do not provide, such as child abuse prevention and treatment services, the department contracts with third parties, and such contracted services can include independent living services, transitional housing, and youth employment programs.

Figure 8

The Department Established an Interagency MOU That Allows It to Partner With Other Agencies and Contractors to Provide Coordinated Services to Foster Youth

Source: Auditor review of department contracts.