2025-601 State High-Risk Audit Program

The California State Auditor’s Updated Assessment of Issues and Agencies That Pose a High Risk to the State

Published: December 11, 2025Report Number: 2025-601

December 11, 2025

2025‑601

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As required by Government Code section 8546.5, my office presents this report about statewide issues and state agencies that represent a high risk to the State or its residents. Our work to identify and address such high-risk statewide issues and agencies aims to enhance efficiency and effectiveness by focusing the State’s resources on improving the delivery of services related to important programs or functions.

In this report, we conclude that the California Department of Social Services met our criteria to be designated as a high-risk agency, and we are adding it to the high-risk list. Because of recent changes to federal law, the State will soon be required to pay a portion of its CalFresh benefits. This cost, which could be as much as $2.5 billion in federal fiscal year 2028, is based on California’s payment error rate, which measures the accuracy of the State’s eligibility and benefit determinations. We also describe updates to the seven existing high-risk state agencies and statewide issues that include the Employment Development Department, the State’s management of federal COVID-19 funds, the State’s financial reporting and accountability, the Department of Health Care Services, information security, the California Department of Technology, and water infrastructure and availability.

We will continue to monitor the risks we have identified in this report and the actions the State takes to address them. For example, our office has recently initiated more in-depth high-risk audits of Medi-Cal eligibility determinations and the State’s financial reporting and accountability under the statutory authority provided by our state high-risk program. When the State’s actions result in significant progress toward resolving or mitigating such risks, we will remove the high-risk designation according to our professional judgment.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ACFR | Annual Comprehensive Financial Report |

| CAP | Corrective Action Plan |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control |

| EDD | Employment Development Department |

| HCD | Department of Housing and Community Development |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LAO | Legislative Analyst’s Office |

| OBBBA | One Big Beautiful Bill Act |

| PAL | Project Approval Lifecycle |

| PDL | Project Delivery Lifecycle |

| PER | Payment error rate |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| UI | Unemployment Insurance |

| USDA | U.S. Department of Agriculture |

Contents

| RISK AREA | HIGH-RISK AGENCY OR RESPONSIBLE AGENCY | REPORT SECTION | ON LIST SINCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | |||

| New High-Risk Agency | |||

| CalFresh Benefit Obligations | California Department of Social Services | Errors in Calculating CalFresh Benefits Reduce Program Effectiveness and Could Increase Costs to the State Due to Federal Legislation | N/A |

| Retained High-Risk Agencies and Issues | |||

| Unemployment Insurance Program | Employment Development Department—High‑Risk Agency | The Employment Development Department Continues to Struggle with Improper Payments, Claimant Service, and Eligibility Decision Appeals | 2023 |

| State’s Management of Federal COVID-19 Funds | Department of Finance and Various Agencies—High-Risk Statewide Issue | The State’s Management of Federal COVID-19 Funds Continues to be a High-Risk Issue | 2020 |

| State’s Financial Reporting and Accountability | State Controller’s Office and Various Agencies—High-Risk Statewide Issue | Late Financial Reporting Remains a High-Risk Issue | 2020 |

| Medi-Cal Eligibility | Department of Health Care Services—High-Risk Agency | The Department of Health Care Services Has Not Adequately Demonstrated Progress to Resolve Problems With Medi-Cal Eligibility Determinations | 2007 |

| Information Security | California Department of Technology and Various Agencies—High-Risk Statewide Issue | The State’s Information Security Remains a High‑Risk Issue | 2013 |

| Information Technology Oversight | California Department of Technology—High-Risk Agency | The California Department of Technology Has Not Made Sufficient Progress in Its Oversight of State IT Projects | 2007 |

| Water Infrastructure and Availability | Department of Water Resources and the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services—High-Risk Statewide Issue | California’s Deteriorating Water Infrastructure and Climate Change May Threaten the Lives and Property of Its Residents and the Reliability of the State’s Water Supply | 2013 |

| Other Area Reviewed | |||

| Accountability Over Homelessness Spending and Program Outcomes | |||

Introduction

Background

State law authorizes the California State Auditor (State Auditor) to develop a state high‑risk government agency audit program (high‑risk program). Our office implemented this program to improve the operation of state government by identifying and auditing state agencies and statewide issues at high risk for waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or for having major challenges associated with their economy, efficiency, or effectiveness, and recommending improvements as a result. In accordance with this statutory authority, the State Auditor adopted regulations in 2016 that fully implemented the high‑risk program. These regulations provide the criteria we used in determining the list of state high‑risk agencies and statewide issues we present in this report.

Criteria for Determining Whether a State Agency or Statewide Issue Merits a High‑Risk Designation

According to state regulations, a state agency or statewide issue may be added to the State Auditor’s high‑risk list if the agency is at risk of suffering, or the issue is at risk of producing, waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement. Further, a state agency or statewide issue may be added to the State Auditor’s high‑risk list if the agency is at risk of suffering, or the issue is at risk of producing, major challenges associated with economy, efficiency, or effectiveness under circumstances that cause the risk to be high. All four of the following conditions must be present for us to assign the high‑risk designation:

- The waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or the impaired economy, efficiency, or effectiveness may result in serious detriment to the State or its residents.

- The likelihood of waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or the likelihood of impaired economy, efficiency, or effectiveness is great enough, when compared to the level of serious detriment that may result, for there to be a substantial risk of serious detriment to the State or its residents.

- The state agency or agencies that are responsible for a portion of the statewide issue, or could be tasked with responsibility for resolving a portion of the issue, are not taking adequate corrective actions to prevent the risk of waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or the impaired economy, efficiency, or effectiveness from continuing.

- An audit and the agencies’ implementation of the resulting recommendations may significantly reduce the substantial risk of serious detriment to the State or its residents.

When assessing both state agencies and statewide issues, we consider a number of factors to determine whether there is substantial risk of serious detriment to the State or its residents. We consider whether waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or impaired economy, efficiency, or effectiveness are already resulting in serious detriment, whether the detriment to the State or its residents is escalating, and whether changes in circumstances challenging existing state agency controls are likely to result in serious detriment. We also consider various factors that determine whether the risks may result in serious detriment, such as loss of life, injury, or a broad reduction in residents’ overall health or safety; impairment of the delivery of government services; significant reduction in the overall effectiveness or efficiency of state government programs; or impingement of citizens’ rights. Finally, in evaluating whether agencies have taken adequate corrective actions to prevent the substantial risk of serious detriment, we consider factors such as whether the agencies have demonstrated a strong commitment to controlling or eliminating the risk of waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or impaired economy, efficiency, or effectiveness and whether they have made significant progress through action already taken to control or eliminate the risk to the State. We make the final determination of risk level according to our professional judgment.

Removal of High‑Risk Designation

We remove the high‑risk designation under any of the following circumstances:

- A change occurred since the agency or statewide issue was added to the state high‑risk list such that the risk we previously identified no longer presents a substantial risk of serious detriment to the State or its residents.

- The agency has taken sufficient corrective action to prevent the risk from continuing to present a substantial risk of serious detriment.

- We conclude that the risk presented by the agency or statewide issue is not likely to be reduced by performing additional audit work.

State regulations require us to use our professional judgment to determine whether to remove a high‑risk designation. When we remove the high‑risk designation for one of the reasons described above, we continue to monitor the issue or agency and, if the risk reoccurs, we may reinstate the high‑risk designation according to the factors described earlier.

State High‑Risk Reports

Government Code section 8546.5 authorizes our office to audit and to publish reports on any state agency or statewide issue that we identify as high‑risk. In May 2007, we issued Report 2006‑601, which provided an initial list of high‑risk state agencies and statewide issues. We have since issued several reports updating the list of those agencies and issues that represent high risk to the State. Further, as state regulations require, we establish and post to the State Auditor’s website a tentative plan for performing audits regarding state agencies and statewide issues that appear on the state high‑risk list. Finally, we also include on our website a list of all audits that we are performing, including those of high‑risk state agencies and statewide issues.

To update our assessment of high‑risk state agencies and statewide issues, we interviewed knowledgeable staff at the responsible state agencies to gain perspective on the extent of the risks the State faces. We reviewed the efforts that staff at the agencies said were underway and were intended to mitigate the identified risks. We reviewed reports and other documentation relevant to the issues. Finally, we conferred with agencies and interested parties, such as the Department of Finance, the Legislative Analyst’s Office, Office of the Inspector General within the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, and the Little Hoover Commission. Each of the entities we conferred with provided its perspective on high‑risk agencies and issues it believes the State faces, and we analyzed those agencies and issues to determine whether they should be included on the state high‑risk list.

Our discussions with the above entities and our own analysis led us to include an additional agency in this state high‑risk report. Specifically, we are adding the California Department of Social Services as a high‑risk agency. Finally, we explain why we did not include accountability over homelessness spending and program outcomes but discuss our concern with the California Interagency Council on Homelessness’s implementation of legislative requirements.

New High-Risk Agency

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SERVICES: ERRORS IN CALCULATING CALFRESH BENEFITS REDUCE PROGRAM EFFECTIVENESS AND COULD INCREASE COSTS TO THE STATE DUE TO FEDERAL LEGISLATION

Background

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is a federal program, administered by the states, that provides food benefits to low‑income families. Until recently, the federal government paid all benefit costs for the program. In California, the California Department of Social Services (Social Services) administers SNAP through a program called CalFresh. CalFresh is the largest food program in California and provides an essential hunger safety net.

In July 2025, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) became federal law and made changes to SNAP that will increase states’ share of SNAP costs in two ways. First, starting in federal fiscal year (FFY) 2027, which begins on October 1, 2026 and ends on September 30, 2027, states will be responsible for 75 percent of administrative costs for the program rather than the current rate of 50 percent. Second, states meeting certain conditions—likely including California—will be required to pay for a portion of their benefit costs, which has previously been funded entirely by the federal government. The latter of these two changes is likely to have the most significant impact for California.

Beginning in FFY 2028, a state’s payment error rate (PER) will determine the percentage of its SNAP benefit cost for which it is responsible, as the text box shows.1 The PER measures the accuracy of each state’s eligibility and benefit determinations. Payment errors include both overpayments—when households receive greater benefits than they are eligible to receive—and underpayments—when households receive less benefits than they are eligible to receive.

The OBBBA Makes States Partially Responsible for SNAP Benefit Costs, Depending on the States’ Payment Error Rates

1. The OBBBA establishes the following tiers for states’ SNAP benefit cost match:

- A state with a PER of less than 6 percent does not have to contribute to its SNAP benefit allotment.

- A state with a PER that is at least 6 percent but less than 8 percent must contribute 5 percent of its SNAP benefit allotment.

- A state with a PER that is at least 8 percent but less than 10 percent must contribute 10 percent of its SNAP benefit allotment.

- A state with a PER that is 10 percent or greater must contribute 15 percent of its SNAP benefit allotment.

2. The OBBBA increases states’ share of administrative costs by 25 percent.

Source: Federal law.

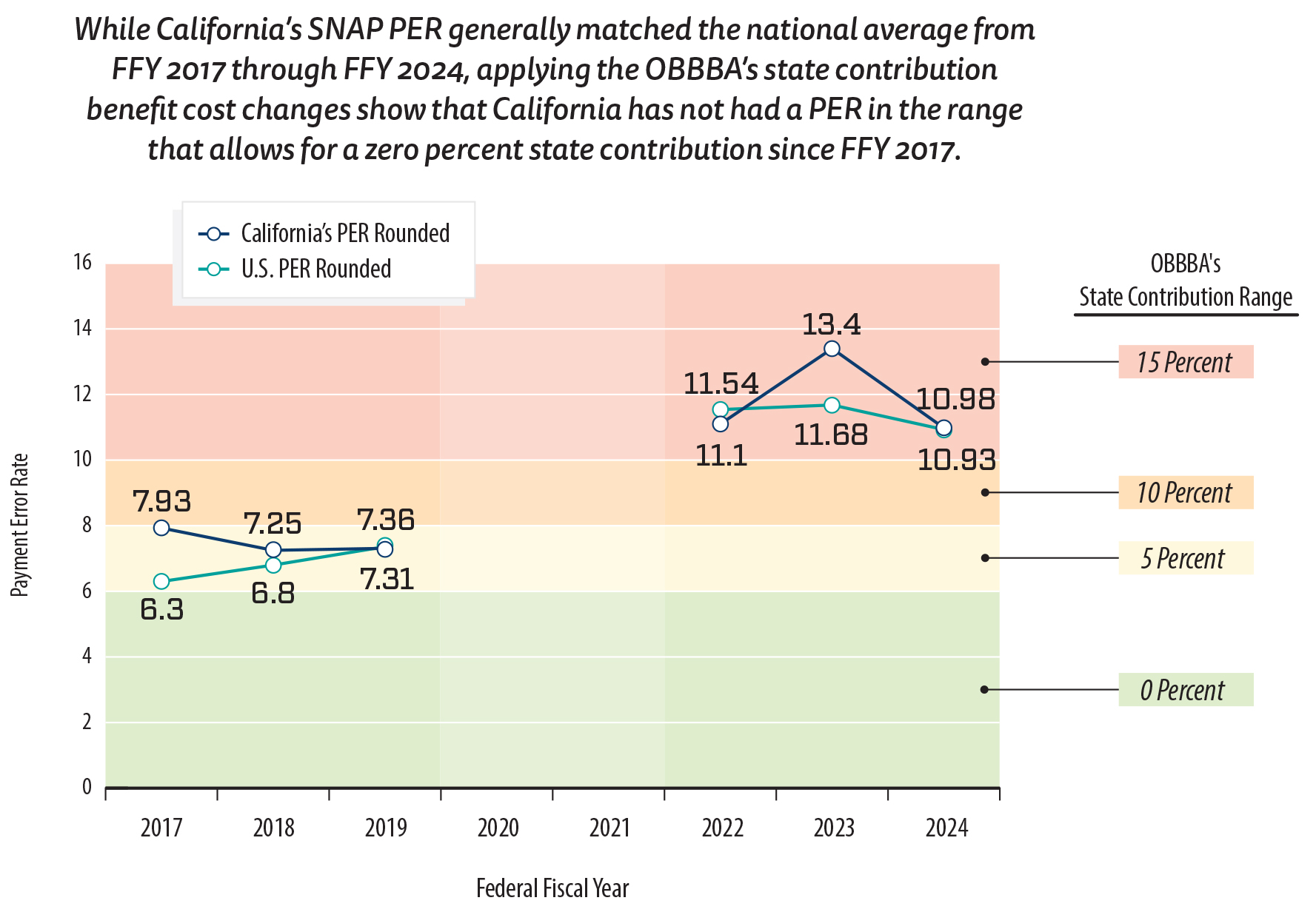

Currently, states with a PER of 6 percent or above must prepare a Corrective Action Plan (CAP) and provide updates to the CAP through regular, semiannual updates to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). In FFY 2024, only nine states reported a PER below 6 percent. California’s PER has remained higher than this threshold and has hovered around the national average since FFY 2017, as Figure 1 shows. California has had to submit CAPs since FFY 2017 based on federal law.

Figure 1

California’s PER Did Not Differ Significantly From the National Average From FFY 2017 Through 2024

Source: USDA data and federal law.

Note: No USDA PER data are available for 2020 and 2021 because of quality control suspensions related to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Figure 1 shows a line graph with points representing California’s PER and the national average PER from FFY 2017 through 2024. Above the graph, there is a note that states “While California’s SNAP PER generally matched the national average from FFY 2017 through FFY 2024, applying the OBBBA’s state contribution benefit cost changes show that California has not had a PER in the range that allows for a zero percent state contribution since FFY 2017.” The y-axis documents the “Payment Error Rate” and the x-axis documents the “Federal Fiscal Year” from 2017 to 2024. The y-axis also documents “OBBBA’s State Contribution Range” by shading the graph’s background to indicate the percent a state would need to contribute to its SNAP benefit costs based on its PER. This shading illustrates that most points in recent years fall within the 15 percent contribution range. The lines for the national average PER and California’s PER are plotted around seven percent from 2017 to 2019. There is a gap between California’s PER and the national average PER from 2020 to 2021. The lines for the national average PER and California’s PER are then plotted around 11 percent from 2022 to 2024. Below the graph there is a note that states “No USDA PER data are available for 2020 and 2021 because of quality control suspensions related to the COVID‑19 pandemic.”

Assessment

Because the recent federal changes to SNAP will require California to shoulder part of the cost of the program’s benefits, CalFresh is now a high‑risk program. If the State does not decrease its PER, it will likely need to spend about $2 billion annually to maintain CalFresh benefits.2 Social Services explained that implementing the necessary corrective actions to decrease the State’s PER will require time. Through an audit of CalFresh, our office could identify specific steps Social Services should take to ensure that it is able to reduce the PER effectively and efficiently.

Because of California’s Payment Error Rate, the State Will Incur Substantially Increased Costs Related to CalFresh

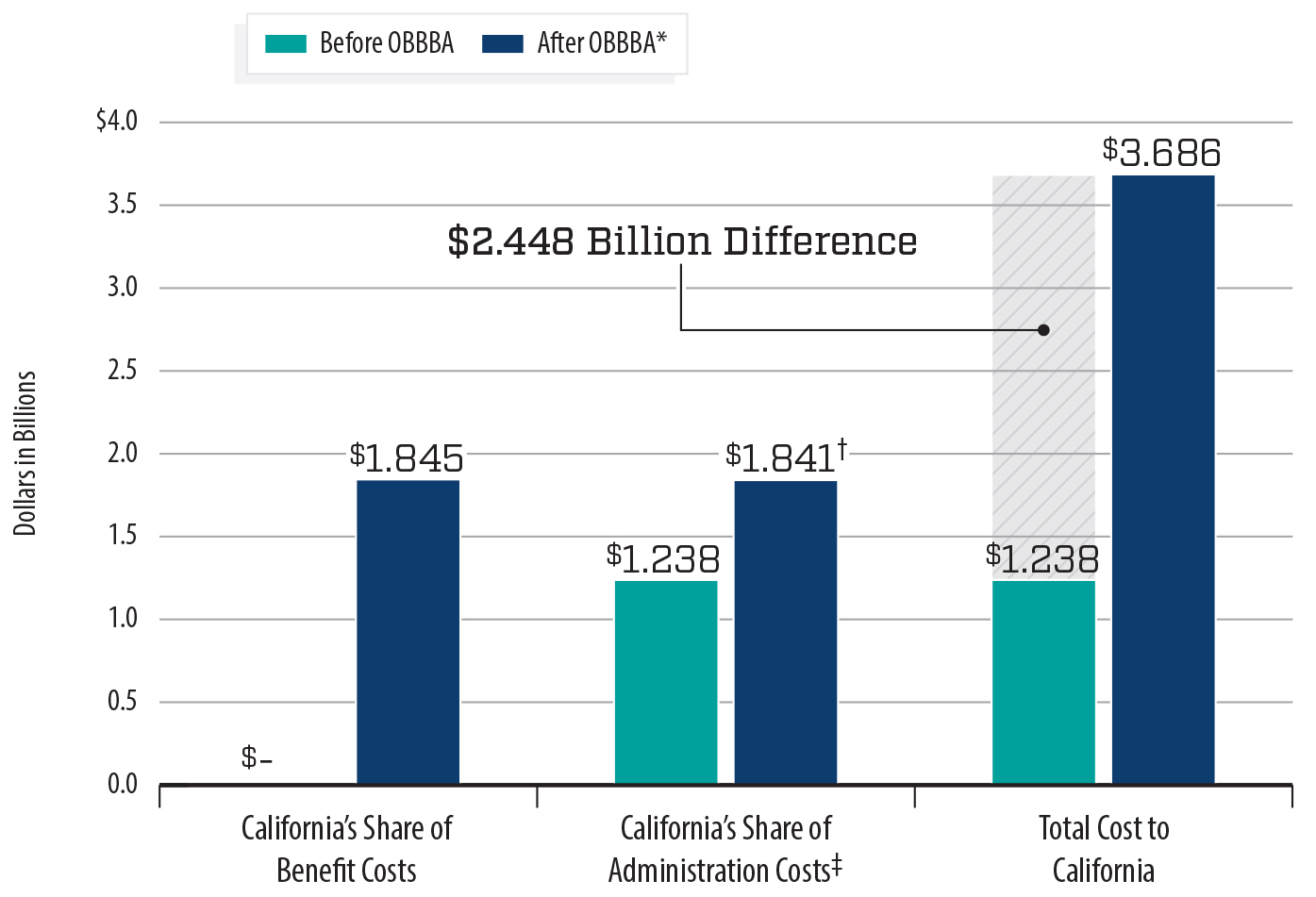

The impending change in SNAP’s funding structure and Social Services’ struggle to lower the PER will significantly impact the State’s budget. In FFY 2024, California had a PER of nearly 11 percent. According to Social Services’ 2025 CAP for FFY 2024, the largest cause of payment errors was related to inaccurate wages and salaries of participants. Specifically, in its CAP, Social Services reported that errors most frequently occur when household income is not accurately captured at the time of the initial application or during recertification. Factors contributing to this error include when county eligibility workers fail to determine a participant’s actual total earned income or when participants fail to report income due to limited understanding of rules. Although this PER is not an unusual rate for a large state and is close to the national average rate, the changes in the OBBBA will require California to pay for 15 percent of its SNAP benefits if it does not decrease its PER to below 10 percent. To estimate the amount of this potential future cost, we calculated 15 percent of California’s state fiscal year (SFY) 2024–25 SNAP appropriation.3 This calculation suggests that if the State’s PER remains unchanged, the OBBBA will lead to more than $1.8 billion in additional costs for State benefits alone, as Figure 2 shows. In addition, the OBBBA will raise the State’s administrative costs by more than $600 million. The State’s total estimated additional costs would therefore be nearly $2.5 billion annually, based on SFY 2024–25 amounts.

Figure 2

Under the OBBBA, California’s Share of CalFresh Costs May Increase by Nearly $2.5 Billion

Source: Auditor‑generated using California’s SFY 2024–25 Spending Plan and federal law.

Note: The OBBBA SNAP changes to federal and state shares of allotment costs go into effect in FFY 2028 and, for FFY 2028, will be based on the State’s PER from FFY 2025 or FFY 2026.

* We calculated these column values using California’s FFY 2024 PER of 11 percent, resulting in the State paying 15 percent of its CalFresh benefit costs. Beginning in FFY 2027, the OBBBA will require the State to pay an additional 25 percent of its administration costs.

† California shares its state CalFresh administration costs with local counties. Currently, 50 percent is federally funded, 35 percent is state funded, and 15 percent is county funded.

‡ Administration costs also include the administration of the California Food Assistance Program.

Figure 2 shows a bar graph comparing different categories of California’s CalFresh costs before and after the OBBBA. Above the graph, there is a key that shows that the graph will contain bars for costs “Before OBBBA” and “After OBBBA”. In the key, there is an asterisk next to “After OBBBA” that is explained by a note below the graph. This note states “We calculated these column values using California’s FFY 2024 PER of 11 percent, resulting in the State paying 15 percent of its CalFresh benefit costs. Beginning in FFY 2027, the OBBBA will require the State to pay an additional 25 percent of its administration costs.” The graph’s y-axis documents “Dollars in Billions” and the x-axis documents three categories of CalFresh costs: “California’s Share of Benefit Costs”, “California’s Share of Administration Costs”, and “Total Cost to California”. “California’s Share of Administration Costs” contains a double dagger mark that is explained by a note below the graph. This note states that “Administration costs also include the administration of the California Food Assistance Program.” “California’s Share of Benefit Costs” documents a bar up to the $1.845 billion mark for costs “After OBBBA”. “California’s Share of Administration Costs” documents a bar up to the $1.238 billion mark for “Before OBBBA” and a bar up to the $1.841 billion mark for “After OBBBA”. The “After OBBBA” bar in this section is labeled with a dagger mark that is explained by a note below the graph. This note states that “California shares its state CalFresh administration costs with local counties. Currently, 50 percent is federally funded, 35 percent is state funded, and 15 percent is county funded.” The “Total Cost to California” section shows a bar up to the $1.238 billion mark for “Before OBBBA” and a bar up to the $3.686 billion mark for “After OBBBA”. This section also contains a transparent bar above the “Before OBBBA” bar to illustrate the $2.448 billion difference between the two bars. Below the graph, there is a note that states “The OBBBA SNAP changes to federal and state shares of allotment costs go into effect in FFY 2028 and, for FFY 2028, will be based on the State’s PER from FFY 2025 or FFY 2026.”

If Social Services is able to lower the PER to between 8 percent and 10 percent, the State will still be responsible for paying 10 percent of the costs of SNAP program benefits, or about $1.2 billion. This is particularly concerning considering that California faces growing multiyear budget deficits, as well as a $20 billion operating deficit for SFY 2026–27. The addition of these significant, new state costs will jeopardize a key program for Californians in need and pose a serious impediment to balancing the State’s budget.

Although Social Services Plans to Decrease the PER, It Is Underprepared for the OBBBA Funding Changes

Although Social Services’ 2025 CAP for FFY 2024 includes a list of actions it intends to take to lower the PER, as the text box shows, some strategies have yet to begin. For example, Social Services intends to launch a multifaceted and multiyear accuracy improvement effort in FFY 2026. In October 2025, Social Services stated that it had been working diligently to evaluate and begin implementing changes in response to the OBBBA, but it needs adequate time to do so. It further explained that although recent state legislation has provided funding for PER reduction work, it has not had time to hire the additional staff and has only just begun to consult with stakeholders and to develop specific strategies and policies. Social Services also added that it will not be able to accurately assess how any changes it makes will impact the PER until it has the opportunity to evaluate and model various strategies.

Social Services’ Planned Actions to Lower the PER

Actions Social Services identified to address the root causes of PER error elements include but are not limited to:

- Assessment of third-party income verification sources

- Integration of payment verification system data

- Creation of a client communication and education advisory subgroup

- Development of a quality control monthly error rate analysis

- Launch of a monthly shared practices and resource kit

Source: Social Services’ PER CAP for FFY 2024.

It is unclear when Social Services’ PER reduction efforts will be implemented and what their impact will be. Given the complexity of the task it faces, we believe that the department is unlikely to lower the PER meaningfully in a timely manner. Because the OBBBA’s changes to California’s contribution will take effect in less than three years and, for FFY 2028, will be based on the State’s PER for FFY 2025 or 2026, at the State’s election, the State will likely need to increase its spending to maintain benefits for CalFresh beneficiaries.

An Audit May Lead to Policy Changes That Significantly Reduce the State’s Future Costs for Maintaining SNAP Program Benefits

Although the immediate cause of the increased expenses to California—federal budget decisions in the OBBBA—is outside of Social Services’ control and our audit authority, the department can and should work to reduce the PER. An audit by our office would assist Social Services in these efforts. In particular, a high‑risk audit could identify potential weaknesses and needed improvements in Social Services’ PER quality control processes, including determining whether the department is adequately measuring the frequency of electronic verification and ensuring client compliance with income reporting requirements. By identifying needed improvements in Social Services’ oversight of CalFresh and providing related recommendations, an audit could help to limit the additional future costs the State may have to pay for SNAP program benefits. In addition, lowering the State’s PER, regardless of federal policy, will enable the State to better maximize the ability of the CalFresh program to help those in need.

Response from Social Services and State Auditor’s comments.

Retained High-Risk Agencies and Issues:

- The Employment Development Department Continues to Struggle with Improper Payments, Claimant Service, and Eligibility Decision Appeals

- The State’s Management of Federal COVID-19 Funds Continues to be a High-Risk Issue

- Late Financial Reporting Remains a High-Risk Issue

- The Department of Health Care Services Has Not Adequately Demonstrated Progress to Resolve Problems With Medi-Cal Eligibility Determinations

- The State’s Information Security Remains a High‑Risk Issue

- The California Department of Technology Has Not Made Sufficient Progress in Its Oversight of State IT Projects

- California’s Deteriorating Water Infrastructure and Climate Change May Threaten the Lives and Property of Its Residents and the Reliability of the State’s Water Supply

THE EMPLOYMENT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT CONTINUES TO STRUGGLE WITH IMPROPER PAYMENTS, CLAIMANT SERVICE, AND ELIGIBILITY DECISION APPEALS

Background

The Employment Development Department (EDD) provides billions of dollars in partial wage replacement benefits each year to Californians who need and seek such benefits (claimants). One of EDD’s primary responsibilities is its administration of the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program. Funded in part by taxes on employers, the UI program provides temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers who meet specific eligibility requirements, including those workers affected by the COVID‑19 pandemic.

In our 2023 State High‑Risk Audit Program report, our office added EDD to the high‑risk list because of inadequate fraud prevention and claimant service, including a high rate of overturned eligibility decisions in its UI program. In Report 2020‑628.2, January 2021, we explained that EDD’s significant missteps and inaction related to fraud prevention during the pandemic led to billions of dollars in unemployment benefit payments that EDD later determined may have been fraudulent.

Moreover, as we described in Report 2020‑128/628.1, January 2021, EDD did not prepare for an economic downturn despite multiple warnings, a key example of which was EDD’s slow efforts to improve its UI call center and overall claimant experience. Because the department did not address longstanding problems with the efficiency of its UI customer service, including its call center, EDD was often unable to answer claimant questions and process claims in a timely manner during the pandemic.

In addition, in our 2023 report, we found that EDD’s eligibility decisions continued to be frequently overturned upon appeal, requiring some UI claimants to face even longer delays than are typical. From 2017 through 2022, the California Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board (appeals board) ultimately overturned in favor of the claimant more than 40 percent of the issues in UI eligibility decisions that claimants appealed. We noted that this rate of overturned decisions is consistent with the high rate of overturned decisions we described in Report 2014‑101, August 2014.

Assessment

EDD continues to be a high‑risk agency because of insufficient improvement in managing its UI program. EDD continues to have high rates of improper UI payments, including fraudulent payments, and it needs to improve the customer service it provides to UI claimants. EDD also needs to take steps to ensure that its eligibility decisions are not frequently overturned on appeal. Although it has made efforts in these areas, in its 2025 assessment, EDD failed to meet acceptable levels in more than half of the measures on which the federal government evaluates its performance. These inadequacies have resulted in a substantial risk of serious detriment to the State and its residents. A high‑risk audit may result in recommendations that could substantially reduce the risks we have identified.

EDD’s Efforts to Reduce Unacceptably High Levels of Improper Payments Including Fraudulent Payments in Its UI Program Are Not Yet Adequate

EDD’s levels of improper payments, including those resulting from fraud, continue to pose a substantial risk of serious detriment to the State. In calendar years 2023 and 2024, its estimated rate of improper payments remained above the acceptable level of less than 10 percent of payments established by the federal government, with its estimated amount of improper payments totaling approximately $1.5 billion over these two years. Further, its estimated rate of fraudulent payments remains above the level it was in 2019, before the pandemic, indicating that the amount of fraud was more than $500 million in 2024 alone.

Although EDD has implemented a number of measures to control improper payments and fraud, some of those measures have been in place for several years and have still not helped to consistently reduce improper payments to acceptable levels. Further, in its plans for countering improper payments, EDD has not always clearly identified the causes of the high amounts, nor has the agency determined how it will use its various measures to bring them to acceptable levels.

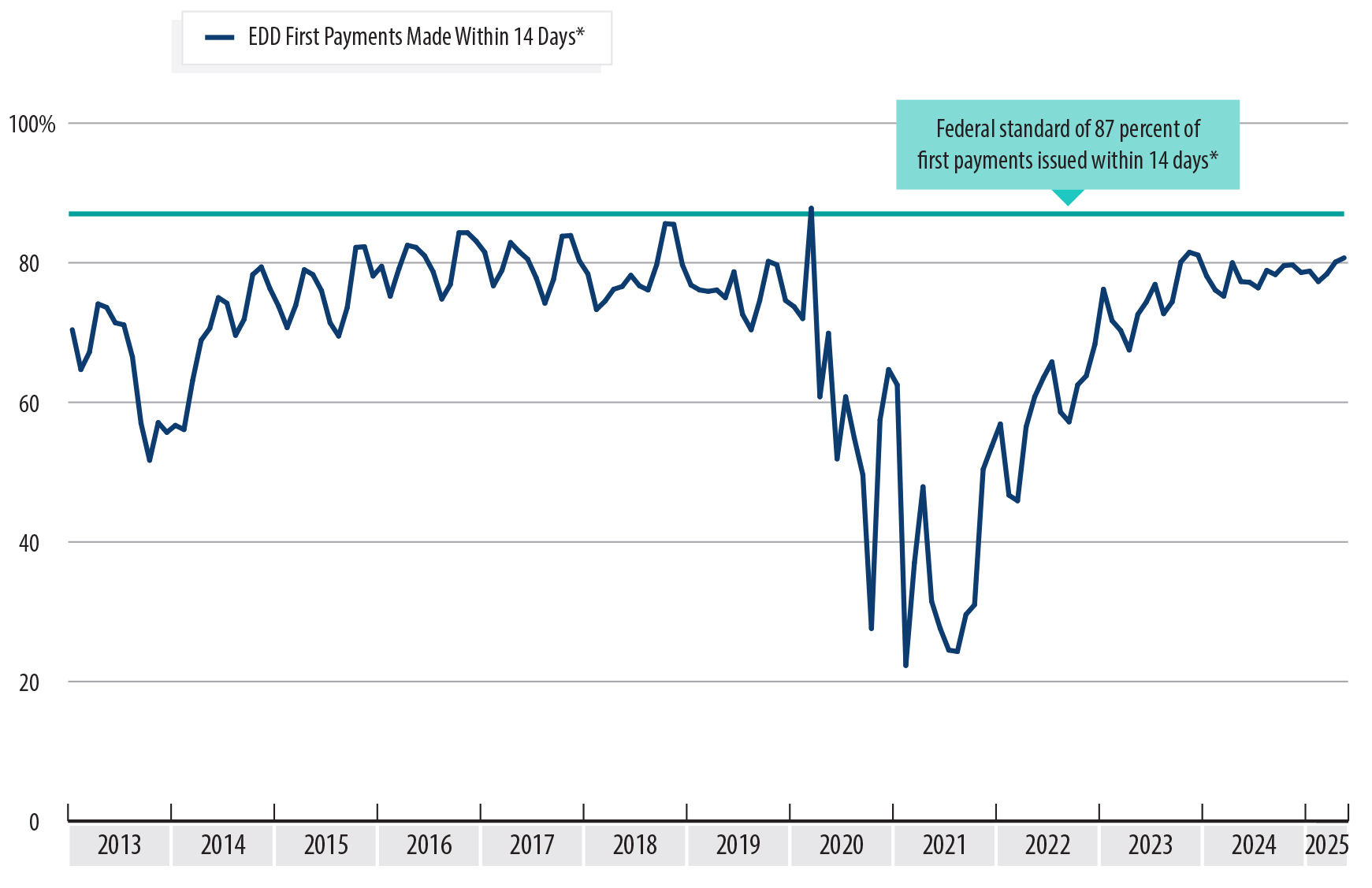

EDD Has Not Provided State Residents With Sufficient Customer Service, Resulting in Significant Challenges to Claimants Obtaining UI Benefits

Despite EDD’s various corrective actions over the years to begin addressing customer service deficiencies in its UI program, it is still unable to consistently meet federal standards. Although EDD has implemented or resolved our January 2021 recommendations related to customer service and has since improved performance, claimants still face difficulty receiving timely payment and often call EDD multiple times for help with their claims. From May 2023 through May 2025, claimants who called EDD did so an average of between two and five times per week. Moreover, as Figure 3 shows, EDD does not meet the federal government’s acceptable level of performance for timeliness of first payment on a UI claim and has met the standard in only one month since January 2013. Therefore, thousands of eligible claimants each month wait longer to receive their benefits than the federal government deems acceptable. In California, this means longer than four weeks, which consist of 14 days after the end of the first eligible week, plus a one‑week waiting period. Although EDD has created a CAP as the federal government requires, and it intends to hire additional customer service staff, its hiring initiatives are delayed, and its customer service continues to fall below acceptable levels of performance.

Figure 3

EDD Has Consistently Failed to Meet the Federal Standard for First Payment Timeliness

Source: U.S. Department of Labor Payment Timeliness Reports.

* State law requires a waiting period of one week before a claimant is eligible to receive UI benefits. In addition, as specified by federal requirements, EDD counts the number of days it takes to issue the payment beginning after the end of the first week the claimant is eligible to be paid, which follows the waiting week.

A line chart showing the percentage of first unemployment insurance payments issued within 14 days compared to the federal standard of 87 percent during the period of 2013 to 2025. The chart indicates that the Employment Development Department (EDD) consistently failed to meet the federal standard across all years, having met the standard in only one month since January 2013. State law requires a waiting period of one week before a claimant is eligible to receive unemployment insurance benefits. In addition, as specified by federal requirements, EDD counts the number of days it takes to issue the payment beginning after the end of the first week the claimant is eligible to be paid, which follows the waiting week. The source for this figure is the U.S. Department of Labor Payment Timeliness Reports.

Many of EDD’s UI Eligibility Decisions Are Not Upheld on Appeal

EDD’s eligibility decisions continue to be frequently overturned on appeal to the appeals board, which contributes to some UI claimants waiting much longer for decisions than federal standards consider acceptable. In 2023 and 2024, the appeals board overturned or modified in favor of the claimant more than 43 percent of the issues claimants appealed. This rate of overturned EDD decisions is only slightly lower than the rate of overturned decisions we noted in both Report 2023‑601, August 2023, and Report 2014‑101, August 2014. Further, claimants appealing EDD’s determinations face a lengthy wait for a final decision. As of March 2025, the appeals board resolved less than 4 percent of first level appeals within 30 days or less, compared to the federal standard of at least 60 percent, resulting in additional delays to claimants receiving benefits.

An Audit May Lead to Policy Changes That Significantly Reduce EDD’s UI‑Related Risks

Additional audit work by our office may assist EDD in mitigating the risk that its handling of the UI program presents. A high‑risk audit would provide independently developed and verified information regarding EDD’s management of the UI program and its challenges. Such an audit would also include analyses that serve as the basis for recommendations to assist EDD in resolving these risks. For example, an audit could evaluate EDD’s efforts to identify potentially fraudulent or improper UI claims, which could lead to recommendations for how to effectively reduce its improper payment rate. A deeper examination of EDD’s UI claimant service and its high rate of denied UI claims overturned on appeal could result in recommendations for how to improve the UI claims process and how to reduce the high rate of denied UI claims overturned on appeal.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

THE STATE’S MANAGEMENT OF FEDERAL COVID‑19 FUNDS CONTINUES TO BE A HIGH‑RISK ISSUE

Background

We first designated the State’s management of federal funds related to COVID‑19 (federal COVID‑19 funds) as a high‑risk statewide issue in Report 2020‑602, August 2020, based on the significant amount of funding granted to the State, the urgent need for the funding, and the rapid nature of the allocation of this funding to state departments, among other factors. As part of its response to the COVID‑19 pandemic (pandemic), the federal government provided the State with $285 billion in federal COVID‑19 funds over the course of two years. The accompanying need to create new programs and to support significant expansion of benefits under existing programs in a short time posed a risk that the State would not manage the funding effectively. As a result, we initially designated the State’s management of these funds as a statewide high‑risk issue in August 2020. However, most of the federal awards to the State have now expired. In fact, the State’s active grants as of July 2025 comprised $37 billion, representing 13 percent of the $285 billion it was awarded. Further, data from the Department of Finance (Finance) show that the State has spent about $35 billion of active grants, leaving about $2 billion available to spend.

In an effort to mitigate the risk that the State would not spend all of its federal COVID‑19 funds, we performed 11 state high‑risk audits of agencies and programs that received the substantial influx of funding and found that they frequently experienced significant hurdles in using those funds. In total, the 11 audits resulted in 85 recommendations. For example, our audit of the Board of State and Community Corrections found that it had allocated funds to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation without justifications and that its allocation methodology did not consider important elements, such as the impact of the pandemic. Of the 85 recommendations we made among the 11 audits, 20 remain unimplemented. Finance similarly completed eight audits of agencies’ use of federal COVID‑19 funds that resulted in 42 recommendations. For example, Finance found that the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) could improve its efforts to develop clear outcome statements and report accurate and complete performance data to Finance in accordance with federal requirements. Five of Finance’s recommendations remain unimplemented as of August 2025. Finance is in the process of completing two additional audits for a program with $540 million of federal COVID‑19 funds that remain available for the State to spend.

Assessment

The State’s management of federal COVID‑19 funds continues to represent a significant risk to California and its residents and will therefore remain a high‑risk issue. As we note in the Background, according to Finance’s data, the amount of federal COVID‑19 funds the State is managing has decreased significantly from the amount initially awarded to the State.4 However, the $2 billion that remains is still a significant amount for the State to manage. Further, $1.3 billion of these funds expires by December 31, 2026, and there is a risk that the State may not fully spend this large amount. Among the awards that have already expired, the State has allowed $820 million to expire unspent. For example, the federal government awarded the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) $418 million for the State’s portion of Immunization Cooperative Agreements for COVID‑19 Vaccine Preparedness. When the grant expired at the end of June 2025, Public Health had spent only $313 million of its award and therefore lost access to the remaining $105 million.

We spoke with officials at Public Health who identified several factors that made spending awards difficult. For example, they indicated that the revocation of the State’s emergency powers in February 2023 associated with the Governor’s State of Emergency caused Public Health to reduce the speed at which it allocated remaining funds to build the infrastructure to vaccinate the population. Further, the officials described how the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) extended the original spending deadline from June 2024 to June 2025 and then extended it again to June 2027. In response to the extensions, Public Health officials stated that they adjusted the program’s plans for spending to continue on to the new deadlines. However, the officials indicated that the CDC later notified Public Health in April 2025 that all the program’s previously approved COVID‑19 grant funds would expire at the end of June 2025, preventing Public Health from fully expending those funds.

The significant remaining amounts and approaching expiration dates for these awards present a risk that the State will not use all of this funding. As for the more than $781 million that will remain available after December 2026, the table shows the eight programs and state departments that manage those funds, and that the awards expire in 2027, 2029, or 2030. Two of these eight programs have spent very little of their awarded funding as of July 2025—one program that focuses on housing has spent only 5 percent of its $155 million award, while the other that focuses on California’s public health infrastructure has spent only 8 percent of its $145 million award. Regardless of the longer period of availability for these awards, the programs’ slow rate of spending presents further risk that the State will not use all its remaining funding.

Additional audit work could help reduce the State’s risk of misusing these funds or of not maximizing their use. The audits that our office and Finance previously performed resulted in a significant number of findings that state departments and their subrecipients had not managed funds according to federal and state requirements. Nearly 20 percent of these recommendations remain unimplemented. Moreover, Finance and our office have not audited many of the programs with remaining funds, and the departments implementing those programs may be managing funds in ways that federal requirements do not allow. Additional audits of this issue could generate recommendations to ensure that these federal COVID‑19 funds are spent prudently, within acceptable time frames, and in accordance with federal and state requirements.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

Response from Finance and State Auditor’s comments.

LATE FINANCIAL REPORTING REMAINS A HIGH‑RISK ISSUE

Background

The accuracy and timeliness of the State’s financial reporting is of vital importance to the State and its residents. A key method the State uses to provide fiscal oversight and transparency is the mandatory Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR) that the State Controller’s Office (State Controller) prepares. The ACFR is composed of financial information from the State’s many departments and agencies, which collectively represent the financial position of the State. The report, which includes the State Auditor’s annual opinion on whether the financial statements are presented fairly in all material respects, provides an important resource for stakeholders, such as the State’s creditors, to use when making decisions about the State’s ability to borrow money affordably. Further, failing to promptly submit the audited ACFR for federal review could result in the withholding of billions of dollars in federal grant awards.

To support its financial reporting needs, the State has focused significant effort on modernizing its financial management infrastructure through the implementation of a project known as the Financial Information System for California (FI$Cal). The scope, schedule, and budget of this nearly $1 billion information technology (IT) project have undergone numerous revisions since it began in 2005. However, despite two decades of continued effort, many state entities continue to struggle to use the system to submit timely data for the ACFR.

In Report 2019‑601, January 2020, the State Auditor added to the state high‑risk list the State’s inability to produce timely financial reports during the transition to FI$Cal. At the time, we noted that since fiscal year 2017–18, the State had issued financial statements late, which could affect the State’s credit rating. The COVID‑19 pandemic also created new financial complexities that affected the State’s financial reporting, such as the increased pandemic‑related spending by EDD and its UI fund. In our previous assessment of high‑risk issues, we noted that the State Controller issued the State’s financial statements for fiscal year 2020–21 later than in previous years—12 months after its traditional deadline and six months after a general extension on financial reporting that the federal government provided because of the pandemic. We also noted that the State’s ACFR for fiscal year 2021–22 had not yet been issued, as of August 2023.

Assessment

The State’s financial statements for fiscal years 2021–22, 2022–23, and 2023–24 were issued in March 2024, December 2024, and September 2025, respectively. Although these recent ACFRs have been issued much sooner than in prior years, the State’s continued inability to produce timely financial reports represents a state high‑risk issue. Because of the significance of this issue, our office has contracted with an independent accounting firm to conduct an external audit of this high‑risk issue, which is currently underway. The audit will examine and identify opportunities for improvement or greater efficiency at the State Auditor’s Office, State Controller, Finance, and five state entities that report financial data material to the State’s ACFR and that did not provide timely and accurate financial reports. We are retaining this issue on the high‑risk list and will reconsider its status upon completion of the contractor’s audit.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

Response from the State Controller and State Auditor’s comments.

THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES HAS NOT ADEQUATELY DEMONSTRATED PROGRESS TO RESOLVE PROBLEMS WITH MEDI‑CAL ELIGIBILITY DETERMINATIONS

Background

The Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services) is responsible for overseeing the State’s implementation of the federal Medicaid program, known in California as Medi‑Cal. Medi‑Cal provides comprehensive health services—including preventive, routine, and emergency care—for eligible residents such as low‑income children, pregnant women, families, and elderly or disabled individuals. As part of this responsibility, Health Care Services ensures that counties’ determinations of eligibility for applicants are appropriate and completed in a timely manner. Health Care Services’ role is pivotal because erroneous determinations of eligibility can result in inappropriate expenditures or in residents experiencing barriers to access needed services.

Our office previously issued Report 2018‑603, October 2018, and Report 2019‑002, October 2020, which both identified discrepancies in Medi‑Cal eligibility records resulting in at least $4 billion in questionable payments. We also found that Health Care Services had suspended the processes it used to ensure that county welfare agencies addressed eligibility discrepancies, including monitoring their adherence to performance standards, requiring CAPs, and, if necessary, imposing financial sanctions, because of difficulties that counties faced during the initial implementation of the Affordable Care Act. As we discuss later, Health Care Services only recently reinstated these processes. In Report 2020‑613, July 2021, we reported that even after considering the effects of the COVID‑19 public health emergency, Health Care Services could still do more to address chronic Medi‑Cal eligibility problems. In Report 2021‑601, August 2021, we reported that Health Care Services remained a high‑risk agency, because it had not corrected discrepancies in its Medi‑Cal eligibility system and that the problem had continued to grow. In our most recent state high‑risk assessment, Report 2023‑601, August 2023, we found that although Health Care Services was positioning itself to make progress on this issue, eligibility discrepancies remained a problem.

Assessment

Although it has made some progress since our last assessment, Health Care Services has not adequately resolved problems involving Medi‑Cal eligibility and will remain on the state high‑risk list. As of April 2025, the number of eligibility discrepancies between the county and state eligibility systems remains only somewhat below the level that we identified in 2021 that was estimated to have caused the State to disburse $1.9 billion in questionable payments. Additionally, as we have previously reported, Health Care Services may also deny benefits to individuals who may be entitled to receive them. The large number of eligibility discrepancies continues to present a substantial risk of serious financial detriment to the State, as well as to some Californians seeking healthcare services.

Since our last report, Health Care Services has issued guidance to counties on how it plans to monitor performance standards, which include standards related to resolving eligibility discrepancies. Counties must provide a CAP if they are noncompliant with the standards, and Health Care Services can issue financial sanctions for failure to demonstrate measurable improvement. However, Health Care Services is still in the first round of this review process, and its schedule indicates that it plans to issue its first report in December 2025. Further, if Health Care Services requires a county to produce a CAP, the county would have an additional two months to develop one. Although Health Care Services has implemented steps to resume oversight of Medi‑Cal eligibility discrepancies, it is yet to be determined whether these actions will result in substantial reductions in outstanding discrepancies and questionable costs.

Because of the ongoing and longstanding risks and its lack of significant progress, Health Care Services’ management of Medi‑Cal benefits remains on the high-risk list. Additional audit work by our office could assist in mitigating these risks by assessing Health Care Services’ progress in addressing ineligible Medi‑Cal recipients and reviewing the processes and effectiveness of Health Care Services’ county reviews. Further, an audit could lead to recommendations to improve the process of resolving eligibility discrepancies.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

Response from Health Care Services and State Auditor’s comment.

THE STATE’S INFORMATION SECURITY REMAINS A HIGH‑RISK ISSUE

Background

Information security is the protection of the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the State’s information assets, and such assets include data, processing capabilities, and IT infrastructure. State law generally requires state entities that are under the Governor’s direct authority (reporting entities) to comply with the information security practices that the California Department of Technology (Technology) prescribes. Technology has the authority to audit reporting entities to evaluate their compliance with information security and privacy policies (compliance audits). Reporting entities are also required to report annually to Technology on compliance with these practices. However, state law does not require entities that fall outside of the Governor’s direct authority (nonreporting entities), such as constitutional offices and those in the judicial branch, to follow Technology’s policies and procedures.5 As the text box shows, we first identified information security as a high‑risk issue in September 2013 and have continued to consider it a high‑risk issue.

Previous State Auditor Reports on Information Security

2013: Technology was performing limited reviews of the security controls that reporting entities had implemented (Report 2013-601)

2015: Many reporting entities had poor controls over their information systems (Report 2015-611)

2018: Although Technology had made progress improving its oversight, information security remained a high‑risk issue because of continued deficiencies in information security controls (Report 2017-601)

2020: Information security remained a high‑risk issue because of continued deficiencies in information system controls (Report 2019-601)

2021: State entities had not demonstrated adequate progress toward addressing deficiencies in their information system controls (Report 2021-601)

2023: Technology had yet to determine the effectiveness of the State’s information security programs, had limited capacity to conduct IT audits, and had not sufficiently improved its oversight of information security (Reports 2022-114 and 2023-601)

Source: California State Auditor reports.

Assessment

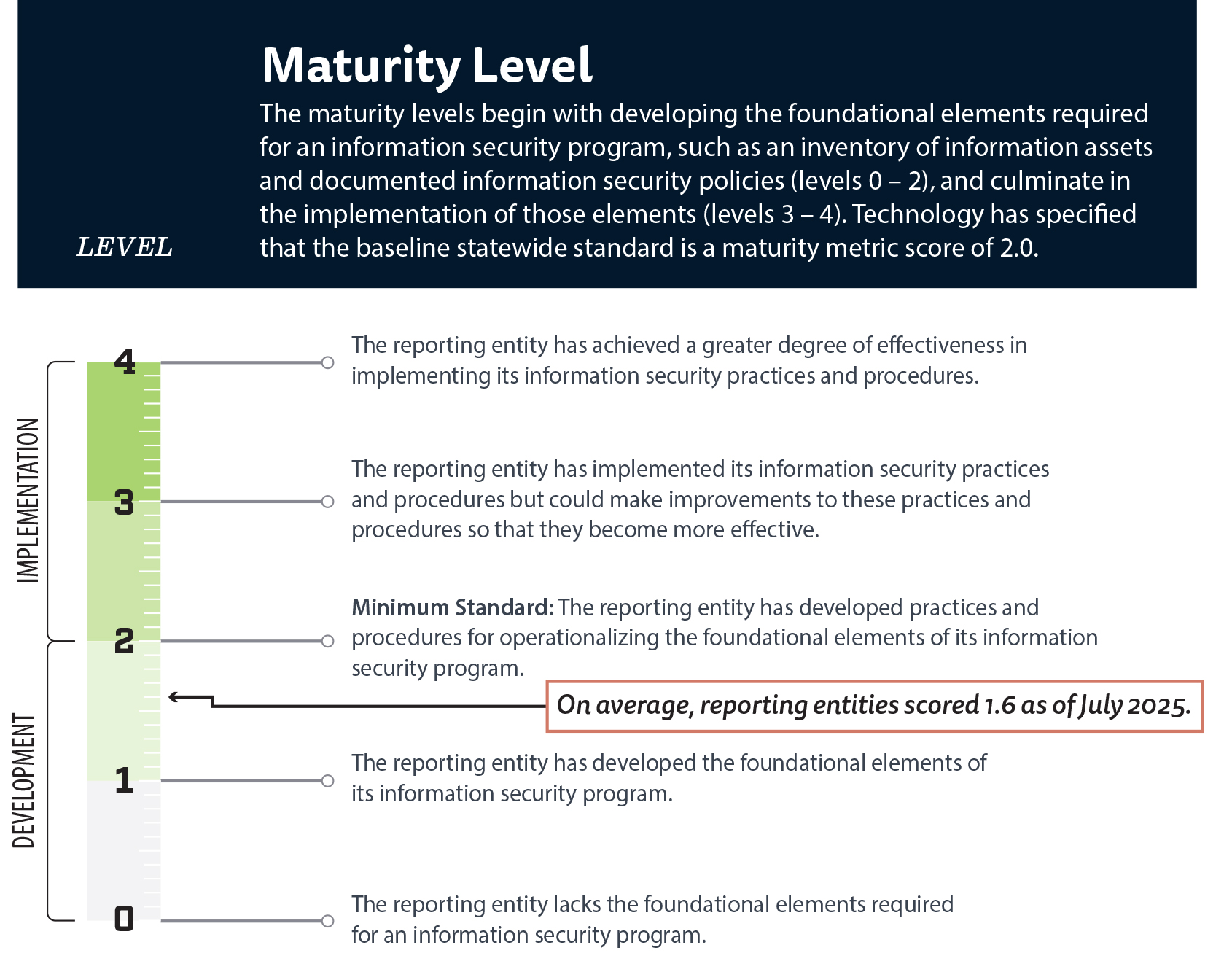

Although Technology has increased its capacity to conduct compliance audits, reporting entities’ cybersecurity maturity continues to be below the state standard, and many nonreporting entities are not complying with cybersecurity requirements; therefore, we will retain information security on the state high‑risk list. Technology is responsible for providing direction for the State’s information security efforts and reviewing the security of reporting entities. To help determine the effectiveness of information security for reporting entities, Technology relies, in part, on audits of the entities’ compliance with the State’s security and privacy policies. In Report 2022‑114, April 2023, we expressed concerns about Technology’s ability to quickly complete audits of all reporting entities. However, from April 2023 through May 2025, Technology increased its capacity to complete compliance audits by growing the number of staff assigned to work on these audits by 26 percent. Additionally, as of August 2025, Technology had audited all reporting entities that are required to receive an audit.

Technology uses technical assessments—which consist of technical analyses of information systems to identify cybersecurity risk—and its compliance audits to summarize each reporting entity’s cybersecurity status into a single score called a maturity metric. Technology asserts that it informs reporting entities that the minimum baseline maturity metric score is 2.0, which indicates that an entity has developed practices and procedures for operationalizing the foundational elements of its information security program. However, as of July 2025, a majority of reporting entities had a maturity metric score below Technology’s standard. Figure 4 shows that the average maturity metric score was 1.6 out of 4.0. This score conveys that, on average, even though reporting entities have developed the foundational elements of their information security program, they are still in the process of developing the practices and procedures to implement their information security programs. This average score is an improvement over the average score we noted in Report 2022‑114, April 2023, although most state entities continue to fall short of minimum standards.

Figure 4

State Entities, on Average, Have Not Reached the Baseline Standard Maturity Metric Score

Source: Technology staff interviews and maturity metric scores.

This chart shows that Information Security maturity levels range from zero to four, where higher scores indicate greater maturity. Levels zero to two represent the development of foundational elements. Levels three through four represent the implementation of the information security program. The statewide baseline standard is a score of two, while the average score for reporting entities is one and six tenths as of July 2025. The source of this figure is Technology staff interviews and maturity metric scores.

Nonreporting entities also need to improve their information security. Legislation that went into effect in 2023 implemented our prior audit recommendation to improve the security of nonreporting entities. Nonreporting entities are now required to perform a comprehensive, independent security assessment every two years and to annually certify to Technology their compliance with certain security requirements, or alternatively, confirm to Technology that they voluntarily and fully comply with Technology’s information security policies and procedures. Technology is then required to review the annual certifications and report to the Legislature a summary of the status of nonreporting entities. However, Technology did not submit to the Legislature its most recent report until August 2025, more than five months after the timeline required by state law. In its August 2025 report, Technology identified that 46 percent of nonreporting entities were out of compliance with either a certification of their information security status or their plan of action and milestones. Technology also reported that the aggregated independent security assessment scores of nonreporting entities were slightly below the state average, indicating that cybersecurity is an issue with both reporting entities and nonreporting entities.

Because cybersecurity poses a significant risk to the State, and the State’s compliance and preparedness remains inadequate, we are retaining this issue on the high‑risk list. The State continues to need improvements in its cybersecurity practices, and although it has been focusing its attention on cybersecurity, it has not substantially mitigated the ongoing risk from inadequate information technology practices. Finally, additional audit work by the State Auditor could assist in mitigating the risk presented by this issue area and could lead to recommendations to improve Technology’s oversight of information security.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

Response from Technology and State Auditor’s comments.

THE CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TECHNOLOGY HAS NOT MADE SUFFICIENT PROGRESS IN ITS OVERSIGHT OF STATE IT PROJECTS

Background

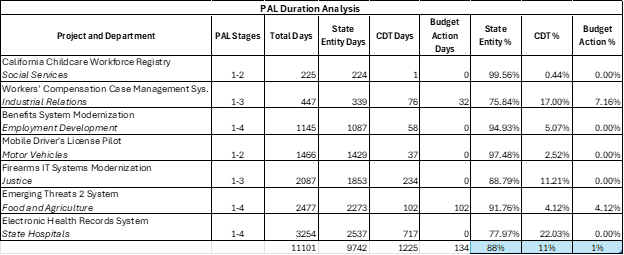

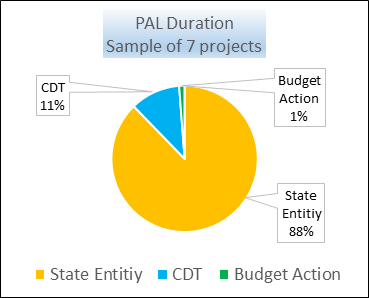

We added IT oversight to the state high‑risk list in our initial high‑risk assessment Report 2006‑601, May 2007, because a number of costly and complex projects were underway at the time, and the State had a history of failed IT projects. State law makes Technology responsible for approving, overseeing, and monitoring the State’s IT projects. Since that initial assessment, Technology implemented the Project Approval Lifecycle (PAL) to, in part, address historical challenges the State has faced in completing IT projects on time and within budget. This four‑stage IT project approval process seeks to ensure that larger projects—those anticipated to cost more than $5 million—include strong business cases, clear objectives, accurate costs, and realistic schedules.

Technology has not been able to demonstrate that PAL has reduced the risk of IT projects failing or exceeding their budgets and timelines. Our state high‑risk assessment Report 2021‑601, August 2021, found PAL’s effectiveness to be unclear because Technology had not demonstrated that PAL was a consistent success across projects of varied importance—especially highly critical and complex projects. We further noted in Report 2022‑114, April 2023, that PAL had several key weaknesses, including its time‑consuming nature, which could delay project approvals. In one instance, we observed that Technology’s process of reviewing procurements took 30 months. We also found that Technology lacked documented metrics to evaluate or demonstrate the effectiveness of PAL, despite a past recommendation from the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) that Technology should report at legislative budget hearings on the quantitative and qualitative measures of success. Moreover, in Report 2023‑601, August 2023, we noted that the weaknesses we observed in PAL persisted and that Technology’s oversight process has continued to be ineffective in addressing other previously identified shortcomings.

Assessment

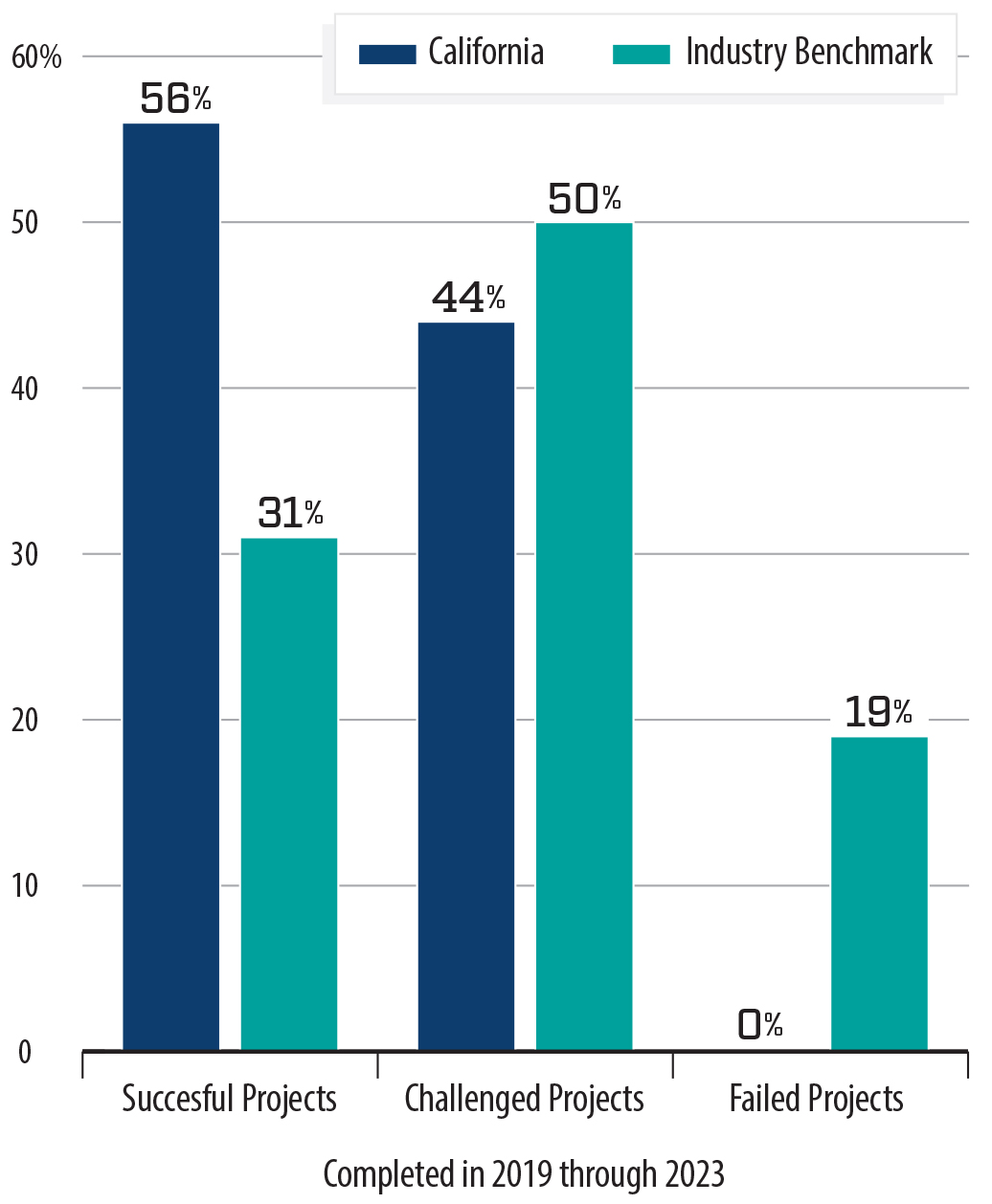

Technology has taken steps to improve the PAL process, although other areas of risk remain. Technology has now fully implemented two of three recommendations from Report 2022‑114, April 2023, that were pertinent to its oversight of IT projects. Specifically, Technology has revised the PAL process to require that proposed projects align with statewide strategic initiatives, and it has completed analyses of its IT project success metrics, including whether projects are completed on time and within budget. Figure 5 shows that according to Technology’s metrics, PAL produced better outcomes than the industry benchmark from 2019 through 2023, resulting in 56 percent of projects being successful, 44 percent of projects being challenged, and no failed projects. However, Technology has not fully implemented our recommendation to revise the PAL process to promote the use of modern approaches, such as modular or Agile, when developing new systems.

Figure 5

PAL Produces a Higher Rate of Successful Projects and Fewer Challenged Projects Than the Industry Standard

Source: Technology’s PAL project outcomes documentation.

Note: A successful project is one that delivers its desired functionality within a 10 percent variance of being on time and within budget. A challenged project is one that delivers its desired functionality but with a greater than 10 percent variance of being on time and within budget. A failed project is one that Technology has terminated. Finally, the industry benchmark is based on the Standish CHAOS Report: Beyond Infinity (2020).

Figure 5 compares California’s IT projects, completed between 2019 to 2023, to industry benchmarks, established in the Standish CHAOS Report: Beyond Infinity (2020). These benchmarks are successful, challenged, and failed. A successful project is one that delivers its desired functionality within a ten percent variance of being on time and within budget. A challenged project is one that delivers its desired functionality, but with greater than ten percent variance of being on time and within budget. A failed project is one that Technology has terminated. For the successful benchmark, California completed projects at a rate of 56 percent, with the industry rate set at 31 percent. For the challenged benchmark, California completed projects at a rate of 44 percent with the industry rate set at 50 percent. For the failed benchmark, California had no projects fail with the industry rate at 19 percent. The source of this figure is PAL project outcome documentation from Technology.

Although Technology has strengthened the PAL process and demonstrated its relative success, PAL remains a protracted stage of IT project development that can delay project execution. As we reported in Report 2022‑114, April 2023, some state agencies have said that the PAL process is too lengthy and delays the approval of projects. Moreover, in a March 2024 press release, Technology expressed its desire for a faster process. However, officials at Technology indicated that factors outside of their control, such as the annual budget process, organizational maturity, the quality of the state agency’s submitted planning documents, and changes in state agency and administration business priorities also contribute to delayed project execution. To evaluate how long projects spend in PAL, we looked at the eight highly critical IT projects currently using PAL as of November 2025. Criticality is determined based on a range of factors, including the project’s technical complexity, business complexity, budget, and durations. We reviewed these highly critical projects because their failure poses the greatest risk to the State. Figure 6 shows that these projects have been in PAL for as few as nine months to as long as 109 months—about nine years. Because the purpose of these IT projects is to address priority strategic needs, these delays in approval pose a risk of impairing the delivery of important government services.

Figure 6

Current Highly Critical Rated IT Projects Have Been in PAL for an Extensive Period

Source: Technology PAL IT project documentation.

Note: We determined each project’s start date in PAL by identifying the date that the requesting agency originally submitted the project’s PAL Stage 1 Business Analysis form to Technology.

The following eight projects are Technology’s current highly critical rated IT projects in PAL.

1. California Child Care Workforce Registry—California Department of SocialServices<h1>

This project has been in PAL since early 2025—9 months.

Social Services currently obtains childcare provider information through a multitude of programs and surveys. This registry will provide a single platform to help ensure that required training for childcare educators is up-to-date and aligns with statutory requirements.

2. Electronic Adjudication Management System—Department of Industrial Relations <h1>

This project has been in PAL since late 2024—16 months.

Industrial Relations’ current system supports more than 8 million cases by managing the adjudication of benefit issues and assisting injured workers in determining how much they are entitled to in workers’ compensation benefits. However, the system software has lacked some basic capabilities since its launch in 2008. For example, in 2018, the system’s inability to reassign cases in mass meant staff manually reassigned more than 58,000 court cases one at a time. This project aims to increase the system capabilities and improve accessibility.

3. Life Outcome Improvement System—Department of Developmental Services <h1>

This project has been in PAL since late 2023—24 months.

Developmental Services’ current consumer electronic records management system does not allow for centralized core business rule management, change management, and integration of case management data across all regional centers, resulting in disparate data sources, poor data consistency and integrity, and non-standard data. Further, Developmental Services’ Uniform Fiscal System is outdated with many limitations including inflexible technology, outdated workflows, and insufficient information security. This project plans to modernize both systems to ensure that needed services are coordinated, received, and accessible and to improve the quality of data received by Developmental Services.

4. EDDNext Project (Previously Re-Imaging Benefits Systems Modernization—EDD <h1>

This project has been in PAL since mid-2022—40 months.

EDD administers several multi-billion-dollar benefit programs, including the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program. Since 2021, we have reported that the UI program struggles to provide adequate customer service and struggles with preventing and detecting fraudulent payments. This project strives to modernize EDD’s benefits system to simplify the claims intake process, boost multilingual service, and mitigate fraud

5. Mobile Driver’s License Pilot—Department of Motor Vehicles<h1>

This project has been in PAL since late 2021—50 months.

Motor Vehicles issues driver’s licenses, identification cards, and REAL IDs, to millions of California residents. This project will build off of Motor Vehicles’ driver’s license and identification card enrollment process and allow California residents to obtain a digital driver’s license and/or identification card through a smartphone.

6. Firearms IT Systems Modernization—California Department of Justice<h1>

This project has been in PAL since the beginning of 2020—71 months.

Justice currently operates 17 different Firearms IT Systems that it reports are inefficient, outdated, and struggles to respond to statutory mandates pertaining to firearms. These IT systems support crucial processes, such as background investigations on individuals who apply for dangerous weapons permits. This project will simplify the patchwork of firearms systems into just two systems to more efficiently and effectively collect public safety information.

7. Emerging Threats 2 System—California Department of Food and Agriculture<h1>

This project has been in PAL since the beginning of 2019—83 months.

Food and Agriculture uses an IT system to collect, manage, and report data used in response to emergency animal disease outbreaks and food safety incidents. However, its IT system is slow, error-prone, and inaccurate. For example, early on in the Newcastle disease outbreak in 2018, Food and Agriculture staff spent two weeks validating and cleaning inaccurate data, which delayed disease surveillance and mitigation. This project will replace the IT system to effectively provide time-sensitive and reliable data for emergency responses.

8. Electronic Health Records System—Department of State Hospitals <h1>

This project has been in PAL since late 2016—109 months.

State Hospitals manages the nation’s largest inpatient forensic mental health system. However, its mainframe patient registration system was built more than 30 years ago and matches patient records incorrectly in 1 of every 20 readmitted patients. This project aims to implement a unified electronic health record system to improve primary care services.

We determined each project’s start date in PAL by identifying the date that the requesting agency originally submitted the project’s PAL Stage 1 Business Analysis form to Technology.

The source of this figure is PAL IT project documentation from Technology.

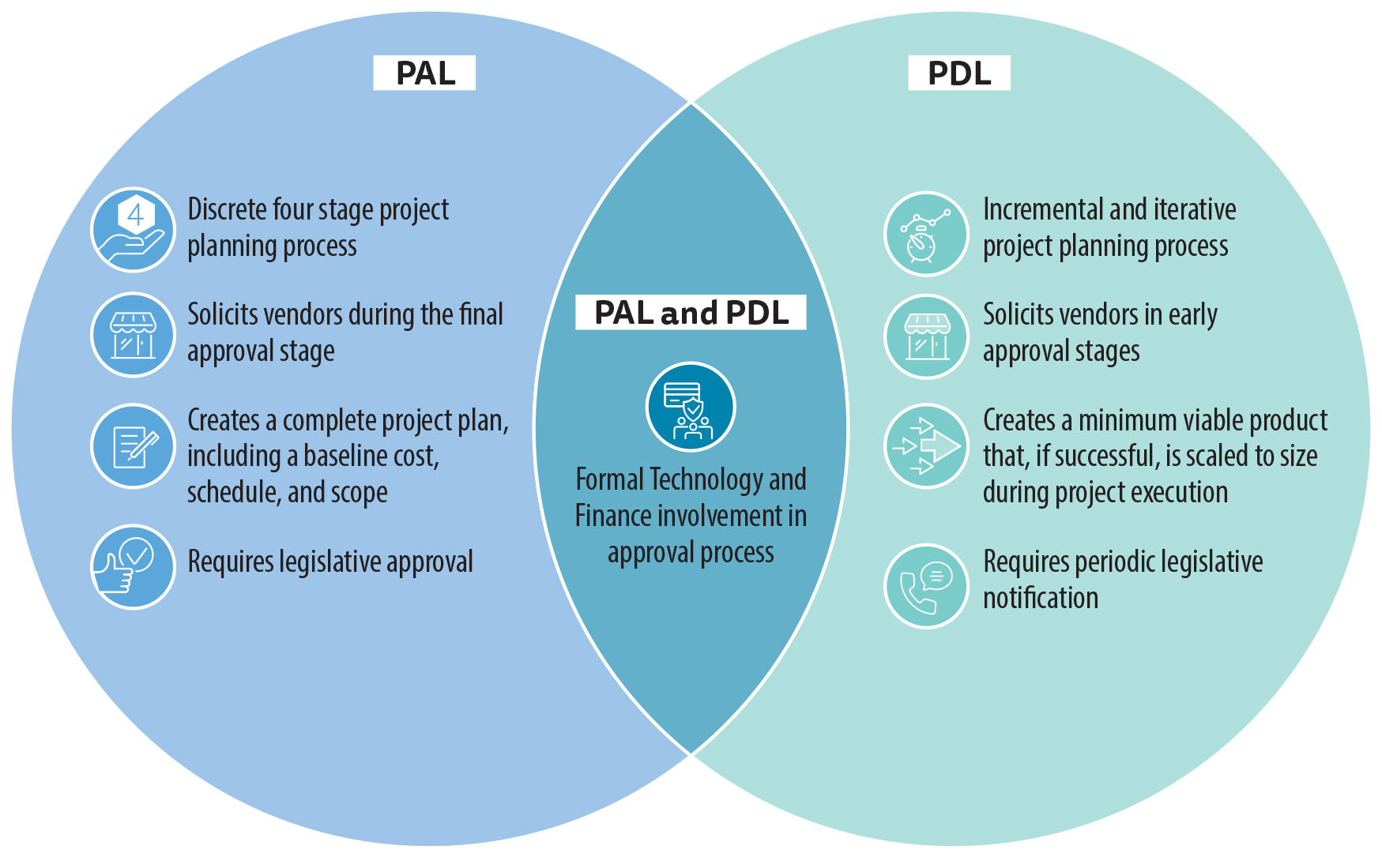

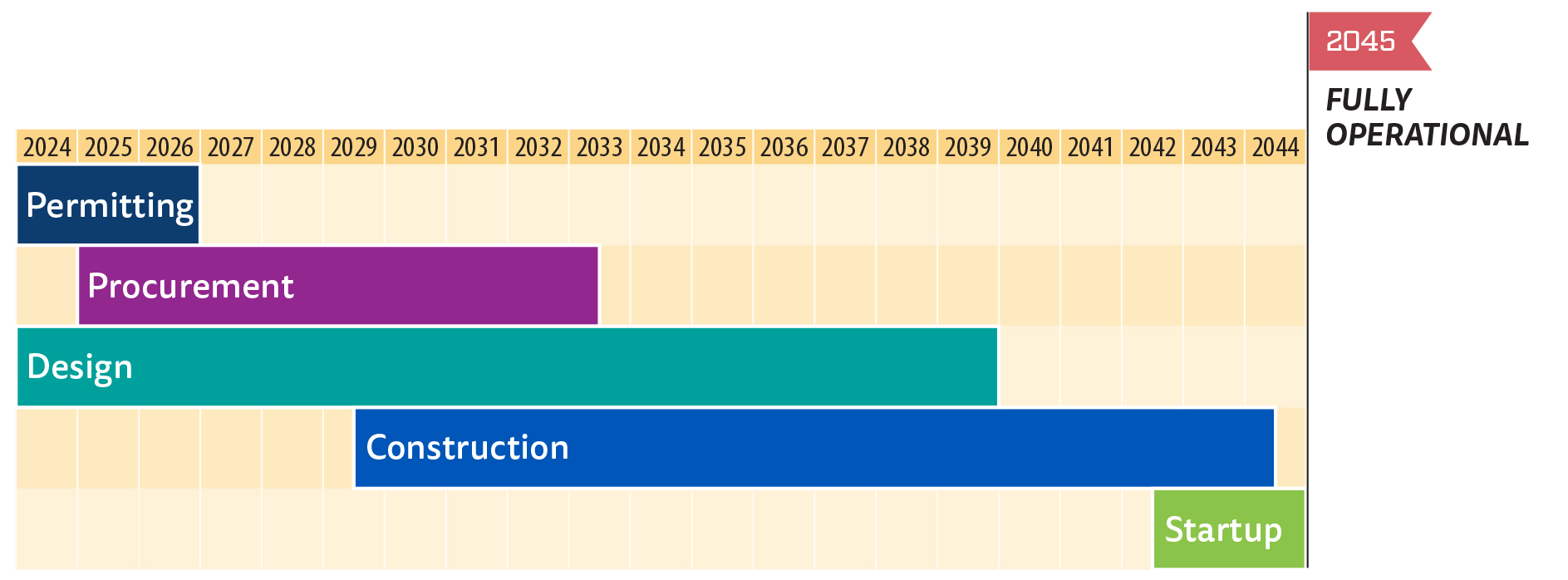

Based on agency feedback about PAL, Technology developed the Project Delivery Lifecycle (PDL) process to allow for a faster, more flexible, iterative approach to IT project planning than the outputs generated from PAL. Technology launched PDL in February 2025, initially for approving only generative artificial intelligence projects, and it will subsequently require all projects to undergo PDL starting in July 2026. Figure 7 points out key differences between the PAL and PDL processes, including the difference in end products. Departments going through PAL leave the process with a complete project plan that addresses details such as baseline project cost, schedule, and scope. In contrast, departments that complete PDL end the process with the creation of a minimum viable product, a technological solution that only includes minimum capabilities but satisfies customer needs and demands before full development. Should the minimum viable product be successful, the department would continue to work with vendors to plan, develop, and implement the remainder of the project. Technology states that the use of proofs of concept and minimum viable products in the PDL process will benefit the State because instead of unwieldy, slow projects, state entities will be able to test ideas first to confirm that they work before fully committing to the project. Technology reports that this, in turn, should help the approval process become clearer and more efficient. This change would also address our remaining outstanding recommendation to Technology.

Figure 7

PAL and PDL Are Designed to Take Different Approaches to Developing IT Projects

Source: LAO assessment of changes to the State’s technology project approval and oversight processes.

Figure 7 is a Venn diagram that compares the similarities and differences of PAL and PDL.

PAL <h1>

1. Discrete four stage project planning process

2. Solicits vendors during the final approval stage

3. Creates a complete project plan, including a baseline cost, schedule, and scope

4. Requires legislative approval

PDL <h1>

1. Incremental and iterative project planning process

2. Solicits vendors in early approval stages

3. Creates a Minimum Viable Product that, if successful, is scaled to size during project execution

4. Requires periodic legislative notification

PAL and PDL <h1>

1. Formal Technology and Finance involvement in approval process

This source of this figure is LAO’s assessment of changes to the State’s technology project approval and oversight processes.

Although the benefits of PDL appear promising, the new process has not yet proven to be successful. In April 2025, the LAO published a preliminary assessment of Technology’s plan to implement PDL, in which it expressed concerns that Technology’s timeline was aggressive and that its planned launch of its final version was premature. The LAO noted that delays in Technology’s first round of IT projects have prevented Technology from providing the Legislature with the information it desires to evaluate the process’s success and its ability to coalesce with the annual budget process. Additionally, the LAO noted that the PDL process may be less transparent than the PAL process. For example, the LAO concluded that the incremental and iterative nature of the PDL process means that baseline cost information and the understanding of subsequent project iterations might not be available until completion of the minimum viable product. Moreover, because the PDL process requires state entities to test ideas first with smaller scale projects, it can lead a project into confidential procurement sooner than previous state IT projects, limiting what information is available for the Legislature to review before approving funding requests through the annual budget process. These risks are of particular concern because of Technology’s intent to transition to reviewing all IT project proposals through the PDL process in July 2026. However, in response to the LAO’s conclusions, Technology stated that PDL will provide similar quality of transparency and documentation for external review as PAL.

Technology has not made sufficient progress in resolving issues with its oversight of IT projects to justify its removal from the high‑risk list. Technology’s PAL process is lengthy and leads to delays. Its PDL process may shorten IT project approval timelines, but Technology does not yet have outcomes to support the success of the new project approval process. Consequently, the circumstances have not changed substantially since our last assessment. Additional audit work by our office could follow up on the findings in Report 2022‑114, April 2023, by more thoroughly assessing Technology’s progress in implementing the PDL process and generating new recommendations.

Status: Retained on the high‑risk list

Response from Technology and State Auditor’s comments.

CALIFORNIA’S DETERIORATING WATER INFRASTRUCTURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE MAY THREATEN THE LIVES AND PROPERTY OF ITS RESIDENTS AND THE RELIABILITY OF THE STATE’S WATER SUPPLY

Background

California’s water infrastructure continues to age and require significant maintenance. We first presented the entirety of the State’s water infrastructure as a high‑risk issue in Report 2013‑601, September 2013, noting that the State’s investment in water infrastructure had not kept pace with its needs. The report also highlighted that the State’s water infrastructure had not seen noteworthy expansion since the 1970s. In fact, at the time of that report, the State’s water storage and delivery system was more than 35 years old, the federal system in the State was more than 50 years old, and some local facilities were about 100 years old. These aging systems require costly maintenance and rehabilitation and, without intervention, pose risks to public safety, water supply reliability, and water quality.

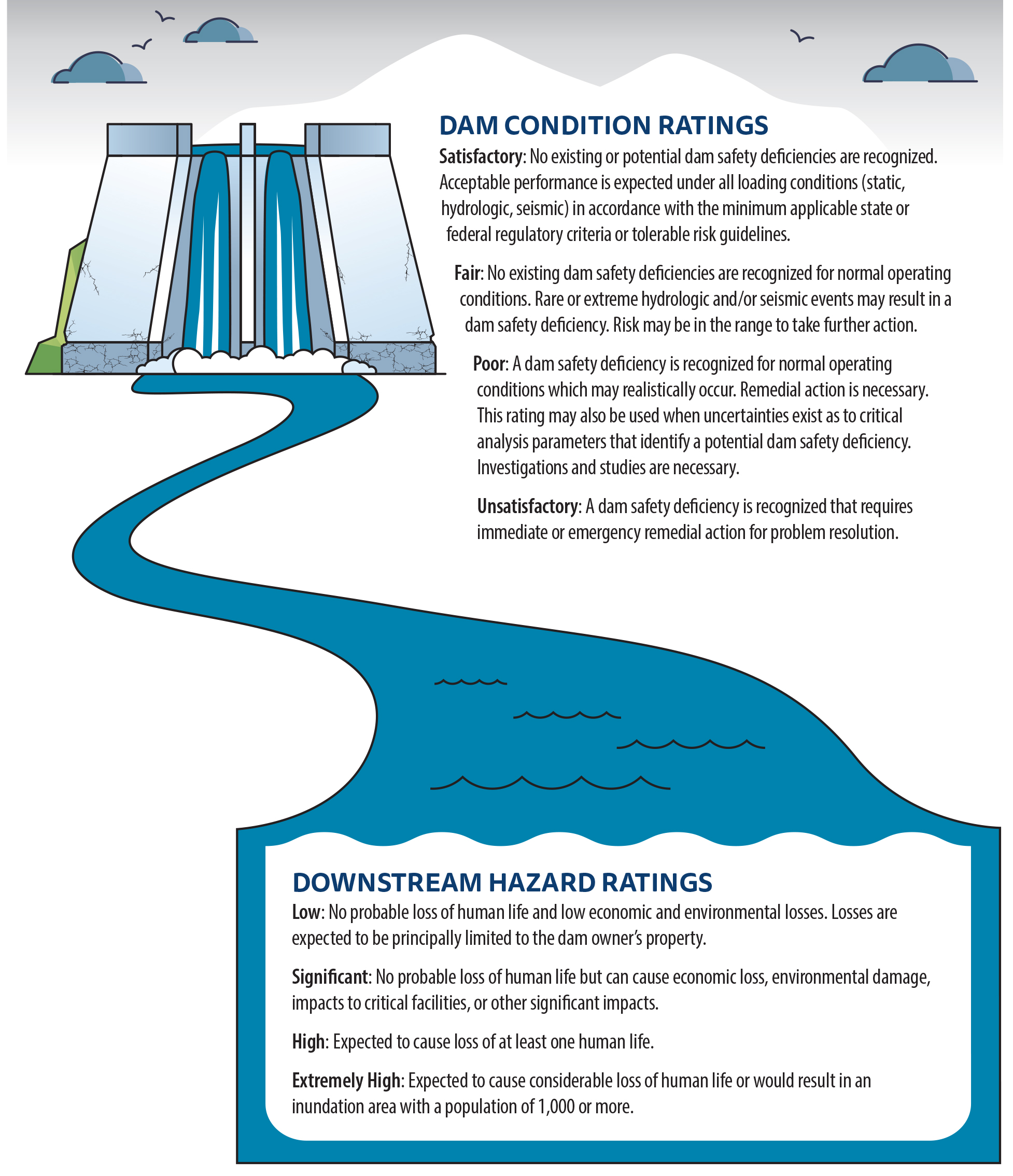

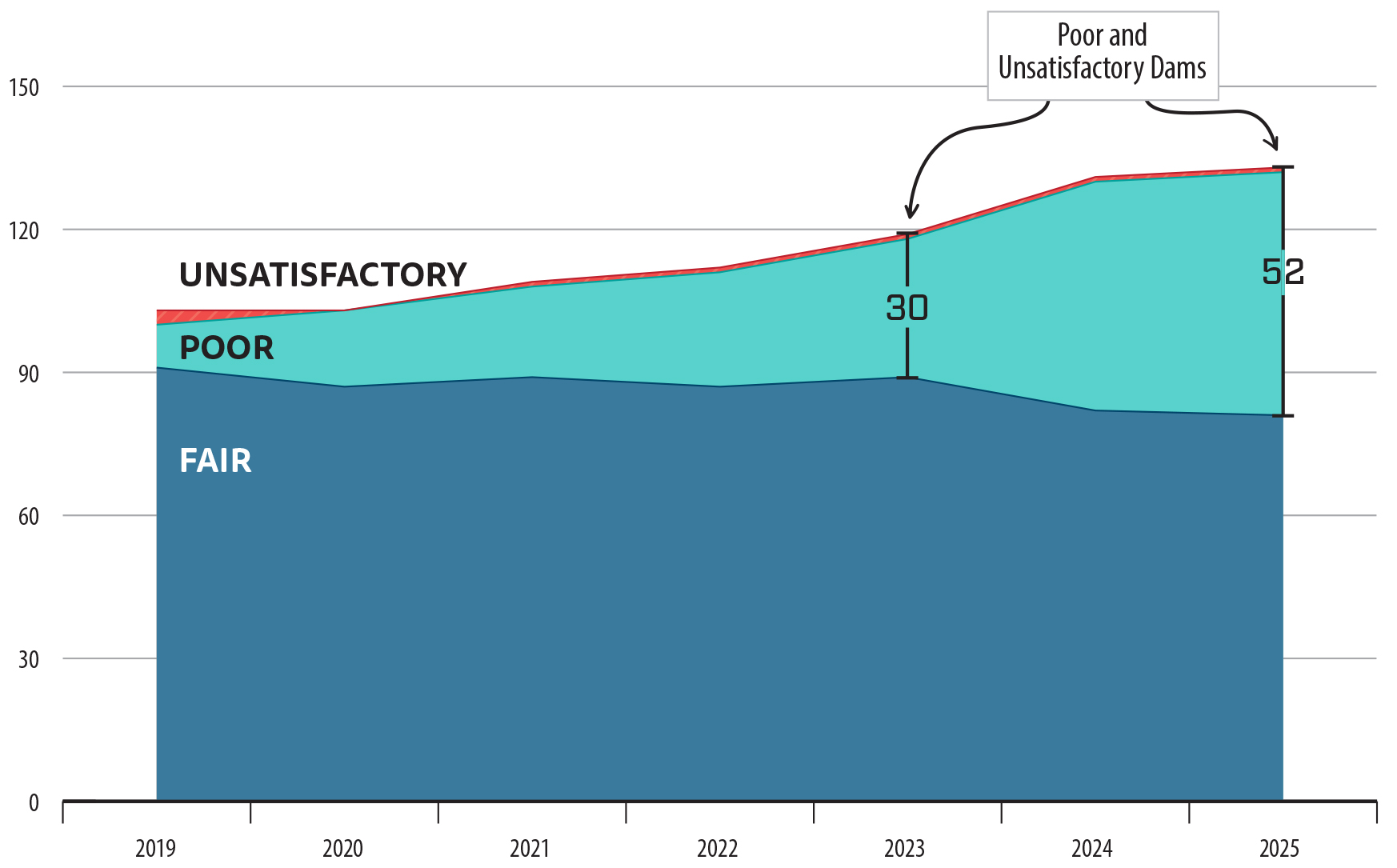

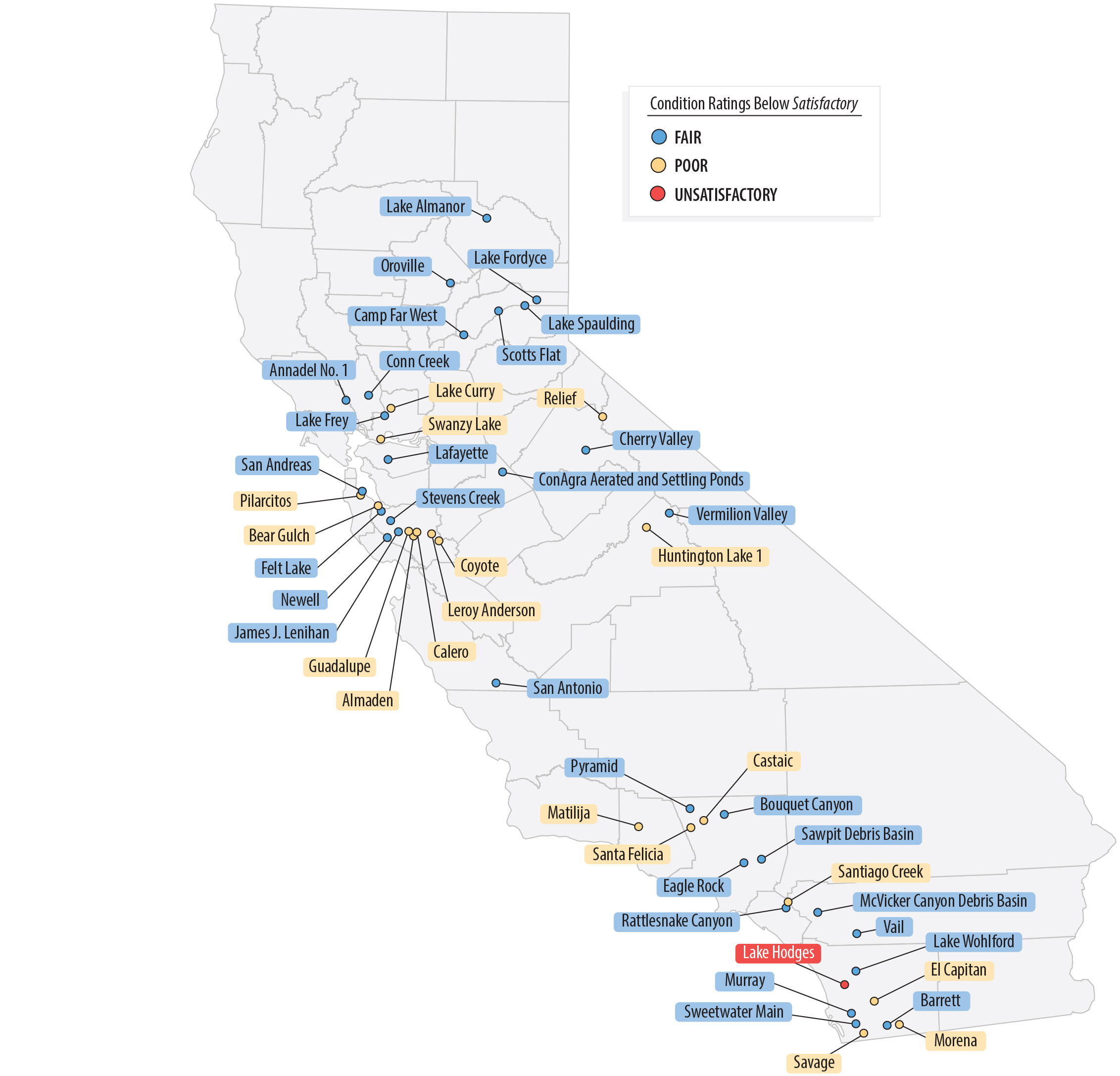

Historically, the State’s dams have posed a significant risk to human life and property. In 2017, the near failure of the Oroville Dam spillway led to our focus on the risk posed by dam safety. The Department of Water Resources’ (Water Resources) Division of Safety of Dams is responsible for overseeing the condition of the State’s more than 1,200 jurisdictional dams for the purpose of determining their safety. The division rates each dam’s condition and identifies the downstream hazard that the dam poses using the ratings that Figure 8 presents. In our previous assessment, we found that 88 dams throughout the State had both a condition rating lower than Satisfactory and a downstream hazard rating of Significant or higher.

Figure 8

Water Resources Rates the Condition and Downstream Hazard of Dams

Source: Water Resources’ dam documentation.

Dam Condition Ratings <h1>

Satisfactory <h2>

No existing or potential dam safety deficiencies are recognized.

Acceptable performance is expected under all loading conditions (static, hydrologic, seismic) in accordance with the minimum applicable state or federal regulatory criteria or tolerable risk guidelines.

Fair <h2>

No existing dam safety deficiencies are recognized for normal operating conditions. Rare or extreme hydrologic and/or seismic events may result in a dam safety deficiency. Risk may be in the range to take further action.

Poor <h2>

A dam safety deficiency is recognized for normal operating conditions which may realistically occur. Remedial action is necessary. Poor may also be used when uncertainties exist as to critical analysis parameters which identify a potential dam safety deficiency. Investigations and studies are necessary.

Unsatisfactory <h2>

A dam safety deficiency is recognized that requires immediate or emergency remedial action for problem resolution.

Not Rated <h2>

The dam has not been inspected, is not under state jurisdiction, or has been inspected but, for whatever reason, has not been rated.

Downstream Hazard Ratings <h1>

Low <h2>

No probable loss of human life and low economic and environmental losses. Losses are expected to be principally limited to the owner’s property.

Significant <h2>

No probable loss of human life but can cause economic loss, environmental damage, impacts to critical facilities, or other significant impacts.

High <h2>

Expected to cause loss of at least one human life.

Extremely High <h2>

Expected to cause considerable loss of human life or would result in an inundation area with a population of 1,000 or more.

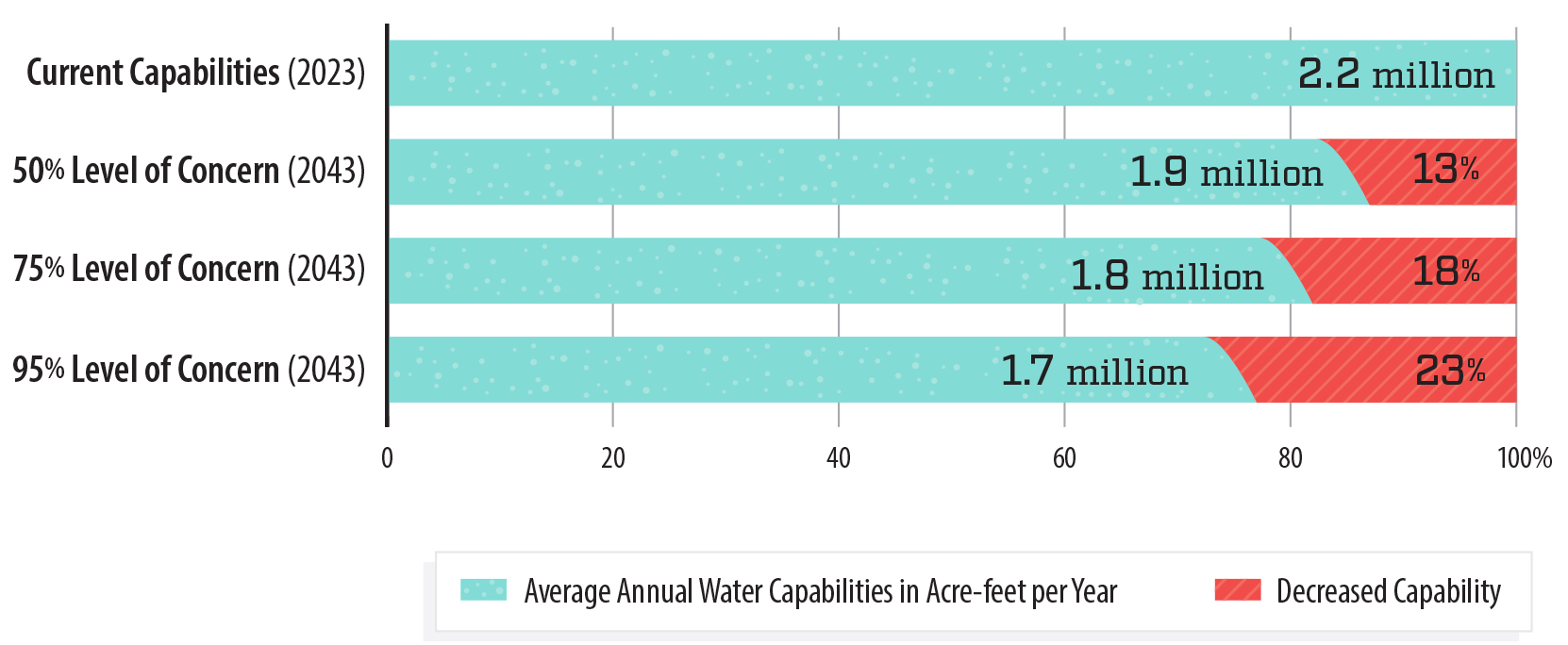

The source of this figure is Water Resources’ dam documentation.