2024-118 State Telework Policies

Although In-Office Work Has Benefits, a One‑Size‑Fits‑All Approach to Telework Is Counter to State Policy and May Limit Opportunities for Significant Cost Savings

Published: August 12, 2025Report Number: 2024-118

August 12, 2025

2024‑118

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee), my office conducted an audit of the rationales that informed changes that the Department of General Services (DGS), the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR), and other departments made to their telework policies. The Audit Committee further asked us to review the State’s costs for maintaining office space for state employees in various telework or hybrid work arrangements. In general, we determined that a one‑size-fits-all approach to telework is counter to state policy and may limit opportunities for significant cost savings.

The Governor’s April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order mandated that employees work in the office two and then four days per week, and they stated that these approaches would enhance certain benefits of in-person work. We evaluated the evidence the Governor cited to support his return-to-office directive and order and determined that they could have made better use of information about departments’ office space needs or the associated costs of those space needs before directing state employees to work an increasing number of days per week in the office. Respondents to our surveys of state departments, managers, and staff—which we sent before the Governor’s March 2025 order—reported that telework is effective and can benefit state departments and employees by lowering costs and improving recruitment and retention without negatively affecting productivity, collaboration, or service.

Based on the two-day in-office requirement from the April 2024 directive, we estimated that in fiscal year 2024–25, 19 selected departments spent almost $117 million on nearly 3.2 million square feet of office space that was often unused in the seven large state-owned office properties we reviewed. To the extent the state can reduce this unused office space, we concluded that telework can generate significant savings for the State when employees can telework three or more days per week. However, the State cannot realize these savings with a four-day in-office schedule, which the Governor’s March 2025 executive order required.

My office also assessed the rationales behind changes that DGS, CalHR, and four other departments made to their telework policies and practices, and we found that only three of the six departments had partially evaluated their telework programs. However, DGS has not established criteria required by state law that would facilitate departments’ evaluations of their telework programs. Ultimately, departments generally relied on intangible factors and direction from external entities when changing their telework practices.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CalHR | California Department of Human Resources |

| CalPERS | California Public Employees’ Retirement System |

| Caltrans | California Department of Transportation |

| CARB | California Air Resources Board |

| CDT | California Department of Technology |

| CDTFA | California Department of Tax and Fee Administration |

| DGS | Department of General Services |

| DHCS | Department of Health Care Services |

| FTB | Franchise Tax Board |

| SAM | State Administrative Manual |

| SPB | State Personnel Board |

| SSA | Staff Services Analyst |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

State law declares that telework can be an important means to reduce air pollution, traffic congestion, and the costs of commuting and that it can stimulate employee productivity and give workers more flexibility and control over their lives. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to an emergency stay-at-home order that resulted in the increased adoption of telework by state agencies so that they could continue to provide government services while most individuals in California were required to remain at home. In April 2024 and March 2025, the Governor directed state departments to change their telework policies to require employees to work in the office for a minimum of two and then four days per week, respectively.1 The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed us to evaluate the rationales that informed changes that the Department of General Services (DGS), the Department of Human Resources (CalHR), and other departments made to statewide and department-level telework policies. The Audit Committee further asked us to review the State’s costs for maintaining office space for state employees in various telework or hybrid work arrangements. Our audit found the following:

The Governor’s Return-to-Office Order Could Have Made Better Use of Important Information Regarding Departments’ Needs and Costs

The Governor’s April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order requiring state employees to work more often in the office stated that this approach would enhance collaboration, cohesion, communication, mentorship, and accountability, among other factors they assert to be benefits of in-office work. We sought to evaluate the evidence cited by the Governor in support of these return-to-office mandates.

We found that the Governor’s Office could have used available information about the effects of returning state employees to the office when making return-to-office mandates. Specifically, the Governor’s Office did not gather some important information about departments’ office space needs or the associated costs before directing state employees to work an increasing number of days per week in the office. The Governor’s Office explained that through a combination of qualitative feedback and limited quantitative data, it weighed department-reported performance outcomes and cost savings associated with telework against concerns about long-term organizational culture, collaboration effectiveness, and the ability to onboard and mentor staff.

When we asked the Governor’s Office to provide the research it conducted or referenced, data it used, or any other information upon which it relied when developing its return-to-office orders, it provided us with two articles that support its claims about the benefits of in‑office work. It did not provide us with data it may have used to inform its decisions, such as data specific to State of California employees, their job performance, or the level of service delivery that state agencies and departments provided. It also did not appear that the Governor’s Office used valuable information that DGS collected from departments about their operations and experiences with telework to inform its April 2024 directive or March 2025 executive order. Further, the Governor’s Office issued the executive order without determining beforehand the amount of office space needed to accommodate employees working in the office four days per week or the associated costs. We found that respondents to our surveys of state departments, as well as state managers and staff, believe that telework is effective and can benefit state departments and employees by lowering costs and the amount of needed office space and improving recruitment and retention without negatively affecting productivity, collaboration, or customer service.

Telework Can Generate Significant Savings for the State in Office Costs, Provided That State Employees Telework Three or More Days per Week

According to the statewide telework policy, departments’ telework programs should reduce the amount of required office space and generate savings for the State. However, when considering the hybrid telework requirement of two days of in-office work per week for state employees that was in place when we began this audit, we estimated that 19 selected departments in the seven large state-owned office properties we reviewed often left unused nearly 3.2 million square feet of office space—or about 58 percent of the office space allocated to these departments. We multiplied the amount of unused space in the buildings by the price per square foot for that space to estimate that the departments paid almost $117 million in fiscal year 2024–25 for this unused space.

Teleworking can generate significant savings in office space because it allows departments to reduce the number of workstations by implementing desk-sharing programs and therefore reduce needed square footage. However, these savings are not possible with a four-day in-office schedule, which the Governor’s March 2025 executive order requires. If the State requires employees to work two days in the office, and thereby telework three days per week, DGS has estimated that it could reduce state-owned and leased office space by approximately 30 percent, which we estimate could generate annual cost savings of as much as $225 million. To reduce the State’s office space footprint, the State could divest from or consolidate large state-owned office properties. However, the Governor’s March 2025 executive order requiring in-office work four days per week would largely eliminate the potential for office space savings related to telework because state policy requires departments to provide dedicated workstations for all eligible employees who work in the office more than half of the week. In fact, the State may need to obtain additional office space to accommodate all employees who may eventually return to the office; however, as of June 2025, the State had not determined how much additional office space it would need to obtain.

Some of the Departments We Reviewed Partially Evaluated Their Telework Programs to Inform Their Past Return‑to‑Office Decisions

The Audit Committee directed us in May 2024 to determine the reasons DGS, CalHR, and four additional auditor-selected departments—California Air Resources Board (CARB), California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and Franchise Tax Board (FTB)—made changes to their telework policies. State law requires each state agency to evaluate its telework program relative to criteria that DGS establishes. Although the statewide telework policy, which DGS issued, does not outline a process for departments to follow when evaluating their own telework programs, it does state that telework programs are expected to meet specified goals, such as encouraging employee participation and reducing state office space. However, DGS has not provided guidance for how state departments should evaluate their telework programs’ performance or effectiveness in meeting these goals. Without guidance for how to determine the effectiveness of their telework programs, it is not surprising that only three of the six departments we reviewed partially evaluated their telework programs when making their past return-to-office decisions.

Specifically, we found that five of the six departments primarily based their decisions to return employees to the office before the Governor’s April 2024 directive on intangible factors and external direction. For example, CARB explained that it made its decision to transition to hybrid telework in July 2021 because of value in having direct contact with staff and stakeholders and the ability to enhance employee experiences and growth. CalHR stated that the Secretary of the California Government Operations Agency (CalGovOps) verbally directed CalHR and other entities in the agency to require employees to work two days in the office, which CalHR implemented in January 2024. Further, of the six departments, only three collected information from their employees to better understand the challenges and benefits of telework, and two of those departments used that information to inform decisions related to telework.

DGS’s Oversight of Telework Policies Was Effective

DGS established a telework unit in fiscal year 2022–23 to review telework policies and perform oversight, which led to departments having telework policies that broadly aligned with the statewide telework policy. The telework unit helped departments develop their telework policies by providing technical assistance and guidance, and it created a public dashboard that displayed some of the positive effects of teleworking using data that state departments reported. DGS announced through its dashboard a savings of nearly 50 million commute miles and the avoidance of over 18,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide in December 2023 alone, the last month for which the dashboard published data. The telework unit helped to provide uniformity in telework practices across the State and amassed valuable information that decision-makers could have used to inform changes to telework policies. However, the Legislature ceased funding the unit in fiscal year 2024–25, and the unit no longer exists.

To address these findings, we recommend that if the Legislature would like to achieve cost savings for office space, it should amend state law to require departments to identify positions that can successfully telework three days per week and offer this level of telework to employees. The Legislature should then require these departments to reduce their overall office space usage, if prudent. Further, we recommend that DGS develop guidance for departments to follow when evaluating the effectiveness of their telework programs in meeting the goals listed in the statewide telework policy.

Agency Comments

DGS agreed to implement our recommendation. Because we did not make recommendations to CalHR, CalPERS, CARB, Caltrans, or FTB, we did not expect a response from them.

Introduction

Background

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic (pandemic) led to state agencies’ quick adoption of telework so they could continue to provide government services during the emergency stay-at-home order. The emergency order directed everyone living in California to stay home and made exceptions for only those workers needed to maintain the operations of critical infrastructure sectors. Before the pandemic, the State as an employer had made limited use of telework. State law addressing telework required every state agency to implement a telework plan by July 1995 in work areas in which telework was identified as being both practical and beneficial, although the law does not require the development of a statewide telework policy. The law also declares that telework can be an important means of reducing air pollution, traffic congestion, and commute costs while stimulating employee productivity and giving workers more flexibility in and control over their lives.

DGS’s Role in Statewide Telework Policy and Space Management

State law first made DGS responsible for overseeing and supporting the State’s telework programs in 1990. The text box describes DGS’s telework responsibilities according to current state law. DGS sponsored an early telework research pilot project in 1987 that evaluated the successes and failures of telework across many state departments. By 1990, this pilot found that teleworker effectiveness met or exceeded expectations, that telework enhanced the quality of work life for workers, including those with disabilities, and that telework had significant potential for reducing traffic congestion, air pollution, and energy use. That same year, the Legislature passed a law relating to telecommuting—which we refer to as telework—that established DGS as responsible for overseeing and supporting telework. In 1994, the Legislature amended the statute to direct each agency to develop and implement a telework plan, with the option to follow guidelines DGS developed during the pilot study. Around this time, the World Wide Web entered into the public domain, and the State began developing electronic government, or “e-government,” services through the internet in 2000. By 2005, the State began efforts to consolidate its datacenters and reassign some of departments’ telecommunications responsibilities—including those of DGS—to what is now the California Department of Technology (CDT). However, DGS retained its responsibilities detailed in the telework law. In 2010, DGS published a model telework policy and procedural guide for state departments (2010 model telework policy) that established a framework to guide departments in drafting their individual telework policies.

DGS’s Telework Responsibilities

- Establish a unit for the purpose of overseeing telework programs.

- Coordinate and facilitate the interagency exchange of information regarding the state’s telework program.

- Develop and update policy, procedures, and guidelines to assist agencies in the planning and implementation of telework programs.

- Assist state agencies in requesting the siting of satellite workstations and develop procedures to track the needs of agencies and identify potential office locations.

- Establish criteria for evaluating the state’s telework program.

Source: State law.

In May 2019, DGS initiated a telework modernization project to develop a formal statewide telework policy that would provide managers with tools and standardized processes for overseeing telework, ensure alignment and compliance across departments, and assist in policy implementation and knowledge transfer. DGS formed a workgroup in August 2019 with members from CalHR and CDT to create the telework policy. The workgroup solicited feedback from departments and unions to draft the telework policy.

In October 2021, DGS published the new statewide telework policy in the State Administrative Manual (SAM), as Figure 1 shows. That new policy required departments to establish or revise existing telework programs by October 2022. Among other requirements, the policy stated that departments must identify the employee positions eligible for telework; determine departments’ financial, technological, and security responsibilities; and outline the goals of their telework programs. Whereas the 2021 telework policy mandates that departments establish telework programs, the 2010 model telework policy had only encouraged the use of telework.

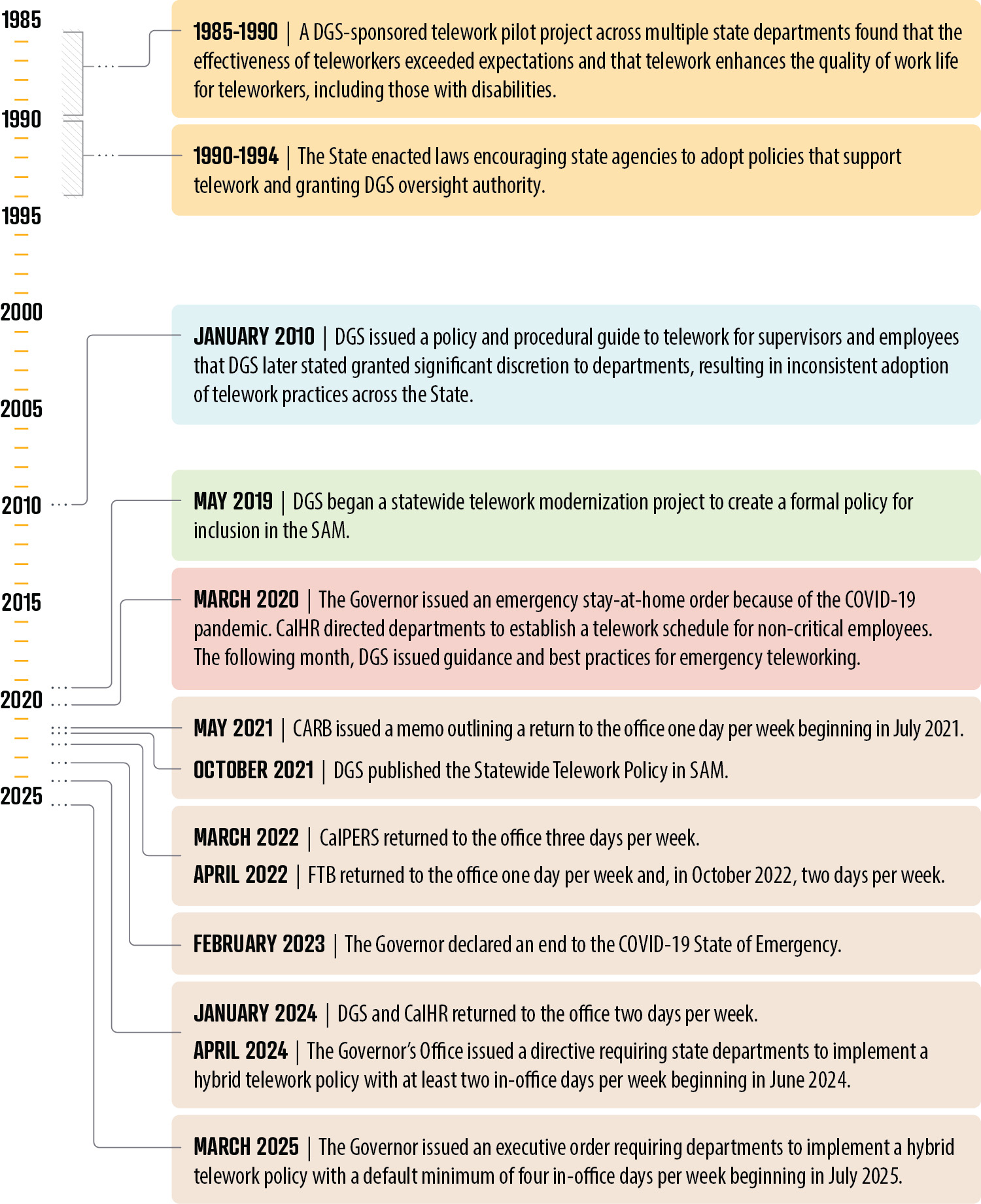

Figure 1

The State’s Policies for Telework Have Evolved Over Time

Source: State laws, executive orders, statewide telework policy, departments’ memos, email correspondence, and interviews.

The State’s Development of Telework Policy Has Evolved Over Time

From 1985 through 1990: A DGS-sponsored telework pilot project across multiple state departments found that the effectiveness of teleworkers exceeded expectations and that telework enhances the quality of work life for teleworkers, including those with disabilities.

From 1990 through 1994: The State enacted laws encouraging state agencies to adopt policies that encourage telework and granting DGS oversight authority.

In January 2010: DGS issued a policy and procedural guide to telework for supervisors and employees that DGS later stated granted significant discretion to departments, resulting in inconsistent adoption of telework practices across the state.

In May 2019: DGS began a statewide telework modernization project to create a formal policy for inclusion in the SAM.

In March 2020: The Governor issued an emergency stay-at-home order because of the COVID-19 pandemic. CalHR directed departments to establish a telework schedule for non-critical employees. The following month, DGS issued guidance and best practices for emergency teleworking.

In May 2021: CARB issued a memo outlining a return to the office one day per week beginning in July 2021.

In October 2021: DGS published the Statewide Telework Policy in SAM.

In March 2022: CalPERS returned to the office three days per week.

In April 2022: FTB returned to the office one day per week and, in October 2022, two days per week.

In February 2023: The Governor declared an end to the COVID-19 State of Emergency.

In January 2024: DGS and CalHR returned to the office two days per week.

In April 2024: The Governor’s Office issued a directive requiring state departments to implement a hybrid telework policy with at least two in-office days per week beginning in June 2024. In March 2025: The Governor issued an executive order requiring departments to implement a hybrid telework policy with a default minimum of four days in-office per week beginning in July 2025.

In addition to maintaining the SAM and its telework responsibilities under state law, DGS is responsible for the management of over 19 million square feet of state-owned office space, in addition to nearly 14.7 million square feet of leased office space.2 For context, data from April 2025 shows that the State owns over 62 million square feet of office space overall. The 2021 statewide telework policy’s goals included the expectation that departments would reduce the amount of office space the State requires.

In the past decade, DGS has regularly engaged in planning for and analysis of its portfolio of office properties, as the text box shows. DGS published a Ten-Year Sequencing Plan in 2016, establishing a plan for future renovation or replacement of state office buildings in Sacramento. DGS’s 2019 Portfolio Plan provided an evaluation of the appropriateness of continued ownership of buildings outside Sacramento in places with less dense concentrations of state employees. The department’s 2023 Real Estate Strategic Plan offered a consolidated statewide analysis, and its February 2025 Real Estate Portfolio Plan evaluates DGS’s inventory of office buildings to determine where in California it makes financial sense for the State to own a building instead of leasing office space. According to the plan, DGS found that commercial leases are generally, though not always, more affordable than ownership over the long term. The 2025 plan incorporated telework into its analysis, including an assumption that state tenants at most properties could reduce their space by approximately 30 percent if they continued to allow up to three days of telework per week. The 2021 telework policy assumed that as departments continued to allow telework, the State could reduce the amount of office space that departments need over time.

Timeline of DGS Real Estate Planning

2016 – Sequencing Plan (Sacramento)

2019 – Portfolio Plan (Non-Sacramento)

2023 – Real Estate Strategic Plan

2025 – Real Estate Portfolio Plan

Source: DGS planning documents.

CalHR’s Role in State Telework

Neither the state law relating to telework plans nor the statewide telework policy define CalHR’s role in overseeing telework. As part of DGS’s workgroup to develop a new statewide telework policy, CalHR contributed primarily as a subject matter expert for labor relations, and it facilitated union negotiations of the policy and telework stipend. Additionally, CalHR collaborated with DGS to provide telework‑related technical assistance to departments through weekly office hours. CalHR also worked with CalGovOps to develop a mandatory training module to help managers and supervisors across departments adjust to a long-term hybrid work environment after the pandemic.

CalHR has general responsibilities in state law to represent the Governor as the employer in employer-employee relations, including collective bargaining. According to these collective bargaining laws, known as the Ralph C. Dills Act, CalHR must engage in a process to provide reasonable written notice to labor unions when there are proposed changes to the terms and conditions of employment via law, rule, resolution, or regulation, and it must give the unions the opportunity to meet and confer regarding those changes. These collective bargaining provisions formed the basis of legal challenges from labor unions to the Governor’s March 2025 executive order that requires departments to adopt telework policies with a default minimum of working in the office four days per week.

Governor’s Actions Related to Telework

In June 2021, the Governor rescinded the stay-at-home order, and in February 2023, the Governor declared an end to the State’s pandemic state of emergency that had led to broad telework adoption by state agencies.

As the text box shows, the Governor’s Office issued an April 2024 directive to all agencies and departments under the Governor’s authority to implement by June of that same year a hybrid telework policy with an expectation that employees would begin working in the office at least two days per week, with case‑by‑case exceptions. The directive asserted that this approach would ensure that all agencies and departments experience the benefits of in‑office work, which the Governor’s Office described as enhanced collaboration, cohesion, and communication; better opportunities for mentorship; and improved supervision and accountability, all balanced with the benefits and increased flexibility of telework.

Governor’s Actions Related to Telework

March 2020

• Executive Order: All residents stay at home to protect public health, subject to certain exceptions. The Governor lifted this order in June 2021.

April 2024

• Directive: Two days per week in office beginning in June 2024 to enhance collaboration, cohesion, communication, and mentorship, with case-by-case exceptions.

March 2025

• Executive Order: Four days per week in office beginning in July 2025 to promote collaboration, cohesion, efficiency, and accountability, with case-by-case exceptions.

Source: Executive orders and Governor’s Office directive.

Nearly a year later, the Governor issued the March 2025 executive order, expanding that requirement to direct agencies and departments subject to the Governor’s authority to require in their telework policies, effective July 2025, a default minimum of four in-office workdays per week, with case-by-case exceptions.3

The March 2025 executive order cited benefits of in-office work like those that the Governor’s Office included in its April 2024 directive. The March executive order further declared that the Governor had determined that in-office work was an operational necessity to maximize collaboration, cohesion, and efficiency, and to maintain public confidence in the efficiency and effectiveness of state government. The March 2025 executive order also cited other reasons for the shift, such as fairness for state employees like custodial and janitorial staff, whose duties involve in‑person work, and trends in the private sector to increase in-office work requirements.

Audit Results

- The Governor’s Return-to-Office Order Could Have Made Better Use of Important Information Regarding Departments’ Needs and Costs

- Telework Can Generate Significant Savings for the State in Office Costs, Provided That State Employees Telework Three or More Days per Week

- Some of the Departments We Reviewed Partially Evaluated Their Telework Programs to Inform Their Past Return-to-Office Decisions

- DGS’s Oversight of Telework Policies Was Effective

The Governor’s Return-to-Office Order Could Have Made Better Use of Important Information Regarding Departments’ Needs and Costs

Key Points

- The Governor’s Office did not gather certain important information, such as departments’ office space needs or the associated costs to return employees to the office, before issuing its April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order for state employees to work an increasing number of days per week in the office.

- Departments and employees who responded to our surveys regarding telework reported that it provides benefits, such as improving recruitment and retention and work-life balance, and that returning to the office two days per week had some counter-intuitive drawbacks, such as reduced collaboration and team building.

The Governor’s Office Did Not Evaluate Certain Available Information When Deciding to Return State Employees to the Office

The Legislature directed us to review potential cost savings associated with telework and to determine the rationale selected state departments used to change their telework policies, both of which led us to review the Governor’s April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order. We determined that a review and assessment of recent telework decisions issued by the Governor’s Office fell under the scope of the audit objectives because the decisions significantly alter the State’s telework practices and affect the State’s ability to reduce its office space footprint. Further, results from our survey of departments, as well as our more detailed review of the telework practices of DGS, CalHR, and the four selected departments, also affirmed the importance of the Governor’s return-to-office mandates as major factors affecting departments’ telework practices.

Following the June 2021 lifting of the stay-at-home order that had led to broad telework adoption by state agencies and the Governor’s February 2023 declaration of the end of California’s pandemic state of emergency, the Governor’s Office directed state departments to return to the office. The California Constitution gives the Governor the supreme executive power of the State and the responsibility to ensure that the law is faithfully executed. Even though the California Supreme Court has recognized that many acts of the Governor are inherently executive or political in nature, requiring the Governor’s exercise of judgment or discretion, it has also held that the ultimate authority to establish or revise the terms and conditions of state employment generally resides with the Legislature, and any authority the Governor exercises in this area emanates from the Legislature’s delegation of a portion of its authority through statutory enactments.

In response to the Governor’s March 2025 executive order, unions raised legal challenges alleging that the order unlawfully usurps the Legislature’s authority by dictating a new telework policy to all state agencies under the Governor’s authority, in contrast to the state law that vests the responsibility to establish telework policies in each state department. In late June 2025, several state employee unions agreed to drop their legal challenges to the executive order after negotiating a one-year suspension until July 1, 2026, of the four-day return-to-office order for their union members. Because these legal challenges and the resulting agreements occurred during our audit, we did not attempt to address the legality of the executive order because generally accepted government auditing standards caution against interfering with ongoing legal proceedings. Nevertheless, we sought to evaluate the evidence the Governor cited in support of his return-to-office mandates.

Executive orders related to telework from 1991 through 2008 and state law have directed agencies and departments to explore ways to embrace telework, and legislative declarations have espoused telework as a means to reduce air pollution, traffic congestion, and commuting costs while stimulating employee productivity and giving workers more flexibility and control over their lives. The law does not include a threshold for the number of days per week worked in either the office or at home. Although the Governor’s April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order also cited the benefit of increased flexibility that telework provides, both mandates cited concerns about long-term organizational culture, collaboration effectiveness, and the ability to onboard and mentor staff as some of the many justifications for returning employees to their offices for an increasing number of days per week.

We presented the Governor’s Office with a series of questions to better understand its rationale for implementing return-to-office requirements. We were particularly interested in reviewing research it conducted or referenced, data it used, or any other information upon which it relied to inform the claims of the April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order that in-person work promotes collaboration, cohesion, creativity, efficiency, accountability, and improved opportunities for mentorship. In May 2025, the Governor’s Office provided responses to our questions about its decision-making process regarding the return-to-office orders, stating that through a combination of qualitative feedback and limited quantitative data, it weighed department‑reported performance outcomes and cost savings associated with telework with concerns about long-term organizational culture, collaboration effectiveness, and the ability to onboard and mentor staff. The Governor’s Office did not provide us with any data it may have used to inform its decisions that were specific to State of California employees, their job performance, or the level of service delivery that state agencies and departments provided.

The Governor’s Office also provided us with two articles that support its claims about the benefits of in-office work.4 The more salient of the two articles identified studies that suggest face-to-face interactions in the workplace can foster the diffusion of knowledge and the generation of new ideas. The article also referred to studies that suggest that telework can slow communications, impede the diffusion of knowledge in an organization, and narrow the scope of collaborative efforts. The same article noted that three of the studies it referenced suggested that one to two days of telework per week improves productivity and leads to happier employees.

Although surveys and questionnaires of state departments that DGS conducted to assess telework were intended to inform decision-makers, it does not appear that the Governor’s Office reviewed this information to inform its April 2024 directive and March 2025 executive order. DGS intended for the information to establish a baseline for decision-makers, meaning that the Governor’s Office could have used the information to learn more about the positive and negative effects of the State’s telework program and to consider the potential consequences of changes to that program. The Governor’s Office did not respond directly when we asked whether it found this information persuasive. Instead, the Governor’s Office noted that the four‑day return-to-office order is based on experience and research about the benefits of in-person work as stated in the Governor’s March 2025 executive order.

As of June 2025, the Governor’s Office had yet to determine the amount of office space needed to accommodate the four-day return-to-office order, which we expected to have occurred before making the decision to implement this requirement. The March 2025 executive order required that, by April 1, 2025, departments submit their plans to DGS to accommodate the increase in in-person work with respect to office space. However, DGS has asserted that the information departments submitted is privileged and has not authorized its release, in part because of its concerns that the information is in draft form, is deliberative, and requires further review. For example, DGS stated that some departments included space needs for vacant employee positions. Based on our review of state buildings, we found that at least some departments would likely need additional office space to accommodate all returning employees. For example, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) would likely need at least an additional 541 workstations, and the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery would likely need at least an additional 123 workstations. The departments would need this space because SAM requires one desk space for each employee who works more than half of the week in the office. Given this potential need for additional office space, we expected the Governor’s Office to have collected this information about the impacts of the March 2025 executive order before it was issued.

Similarly, as of May 2025, the Governor’s Office had yet to determine the costs of implementing the four-day return-to-office order. Potential costs include the costs of acquiring additional office space and increasing parking availability. For instance, DGS submitted a request to the Legislature in May 2025 for $1.5 million in fiscal year 2025–26, and $1 million in subsequent fiscal years, to support the opening of two parking facilities in Sacramento. However, the State has not yet identified the total cost of implementing the four-day in-office executive order. The lack of information about the financial impacts of returning employees to state offices four days per week has led to some confusion about its implementation. The Legislature was unsure how the changes would impact the state budget during hearings in May 2025, and CalHR was unable to provide responses to some questions from members. In fact, in June 2025, a group of 17 assemblymembers signed a letter urging the Governor to delay his implementation of the four-day return-to-office order until there is a better understanding of the impacts of telework on the state budget and workforce.

Respondents to Our Surveys Indicated That Telework Benefits Both State Departments and Employees

We surveyed state department telework representatives and state managers, supervisors, and staff to determine whether their experiences and perspectives align with the benefits and limitations identified in the April 2024 directive. As the text box shows, we performed two surveys—one focused on department perspectives for over 100 departments and one focused on employee perspectives at four departments. We selected these four departments for additional analysis throughout the report based primarily on their size and number of telework-eligible employees. Our surveys included questions about telework policies, department and employee experiences with telework, and their perspectives on changes to telework practices.5 We focused on the Governor’s April 2024 directive, which required employees to return to the office two days per week because we conducted our surveys in early 2025 before the more recent March 2025 executive order.

State Auditor Surveys Related to Telework

Department Survey

- Over 100 departments surveyed from January through February 2025.

- Typically, respondent was the department human resources director, personnel officer, administrative officer, telework coordinator, or employee relations officer (departments’ representatives).

Employee Survey

- 80 employees—including managers and staff—surveyed in February 2025.

- Four departments—California Air Resources Board, California Public Employees’ Retirement System, California Department of Transportation, and Franchise Tax Board.

Source: Survey documentation.

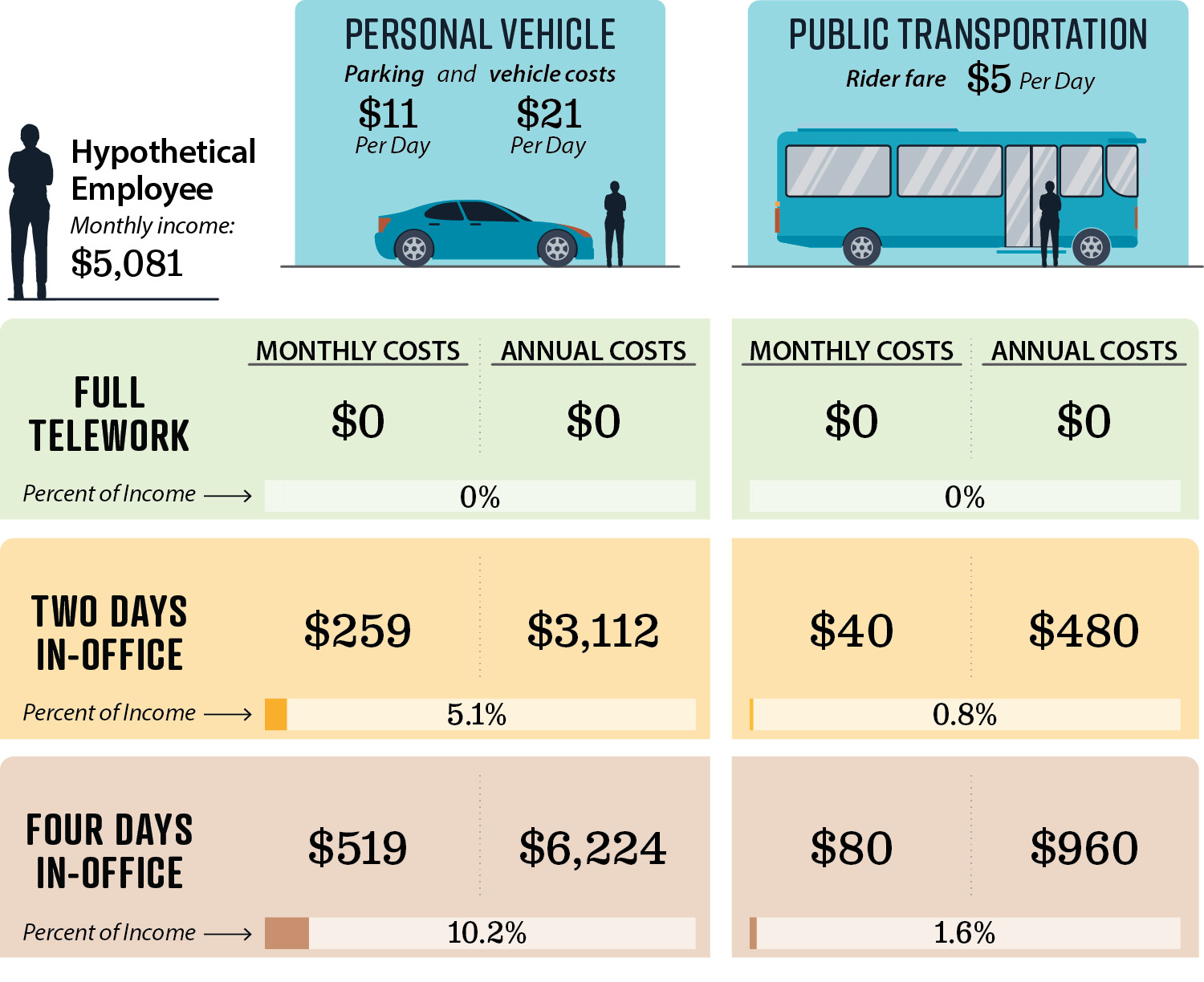

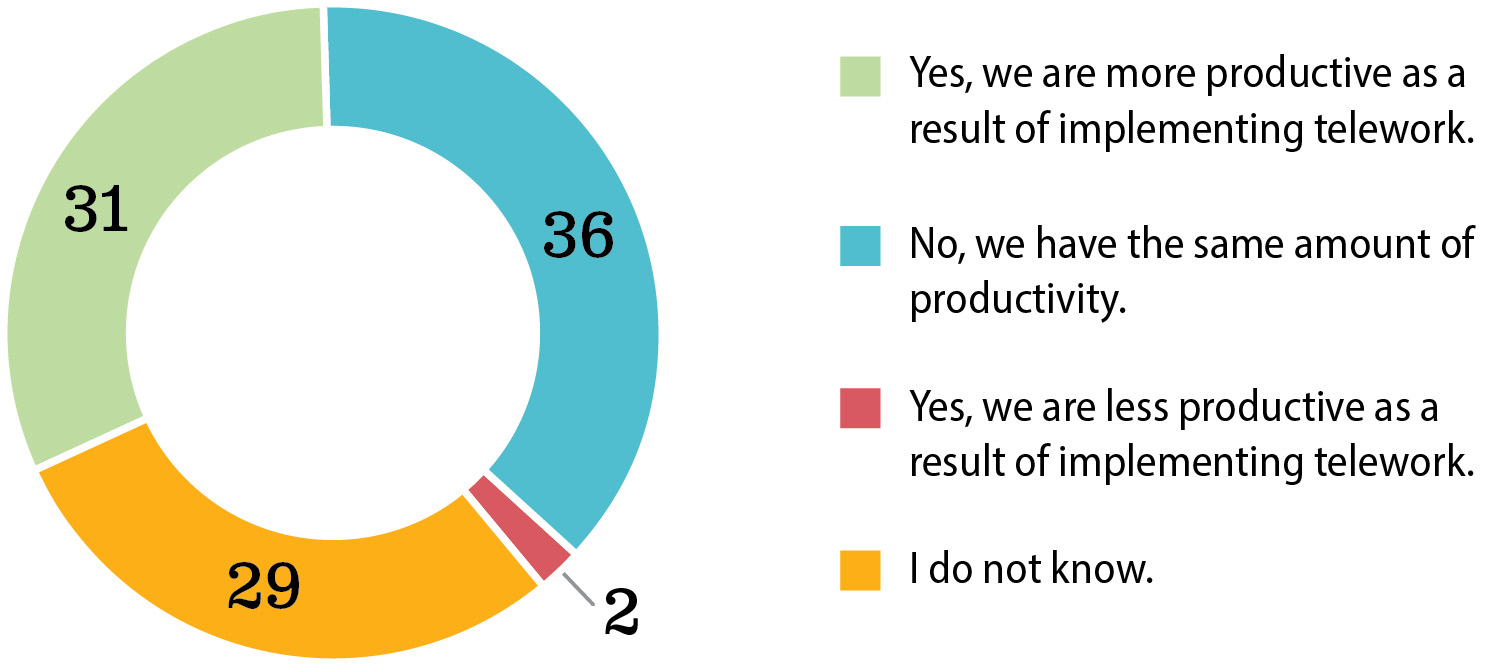

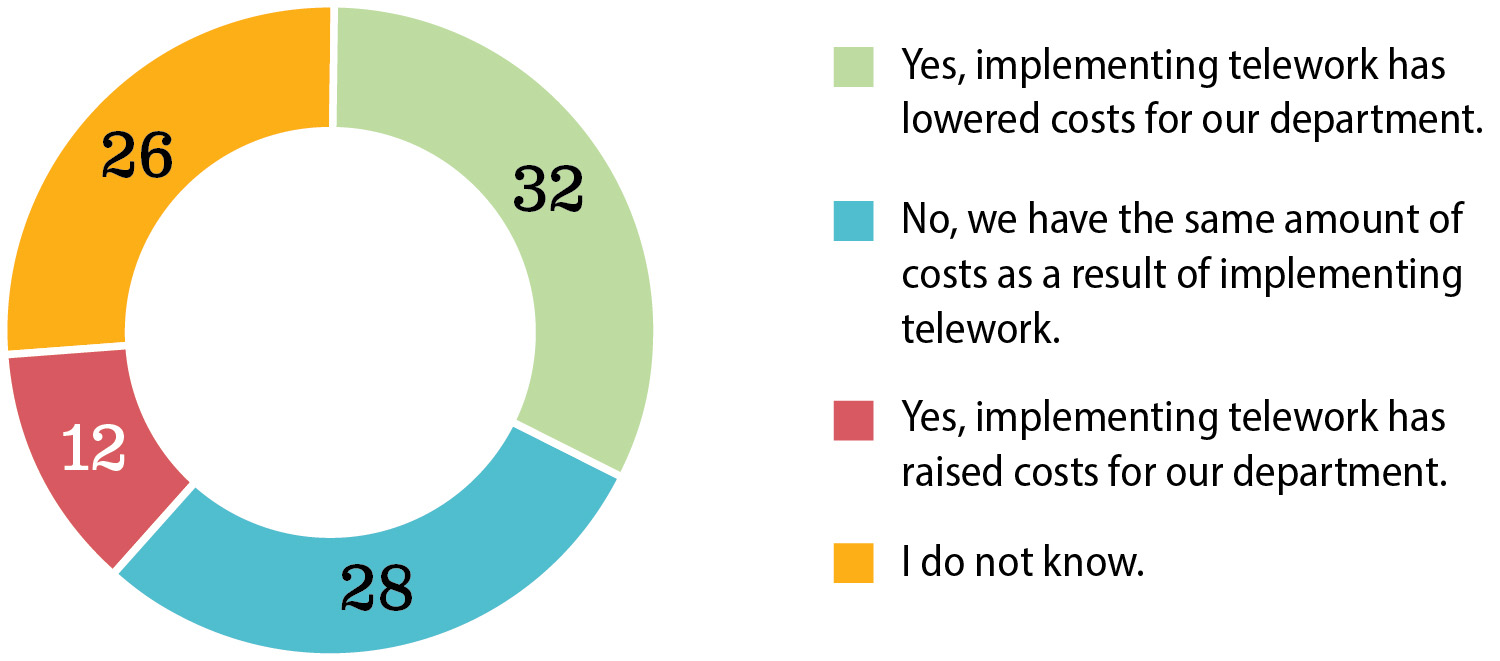

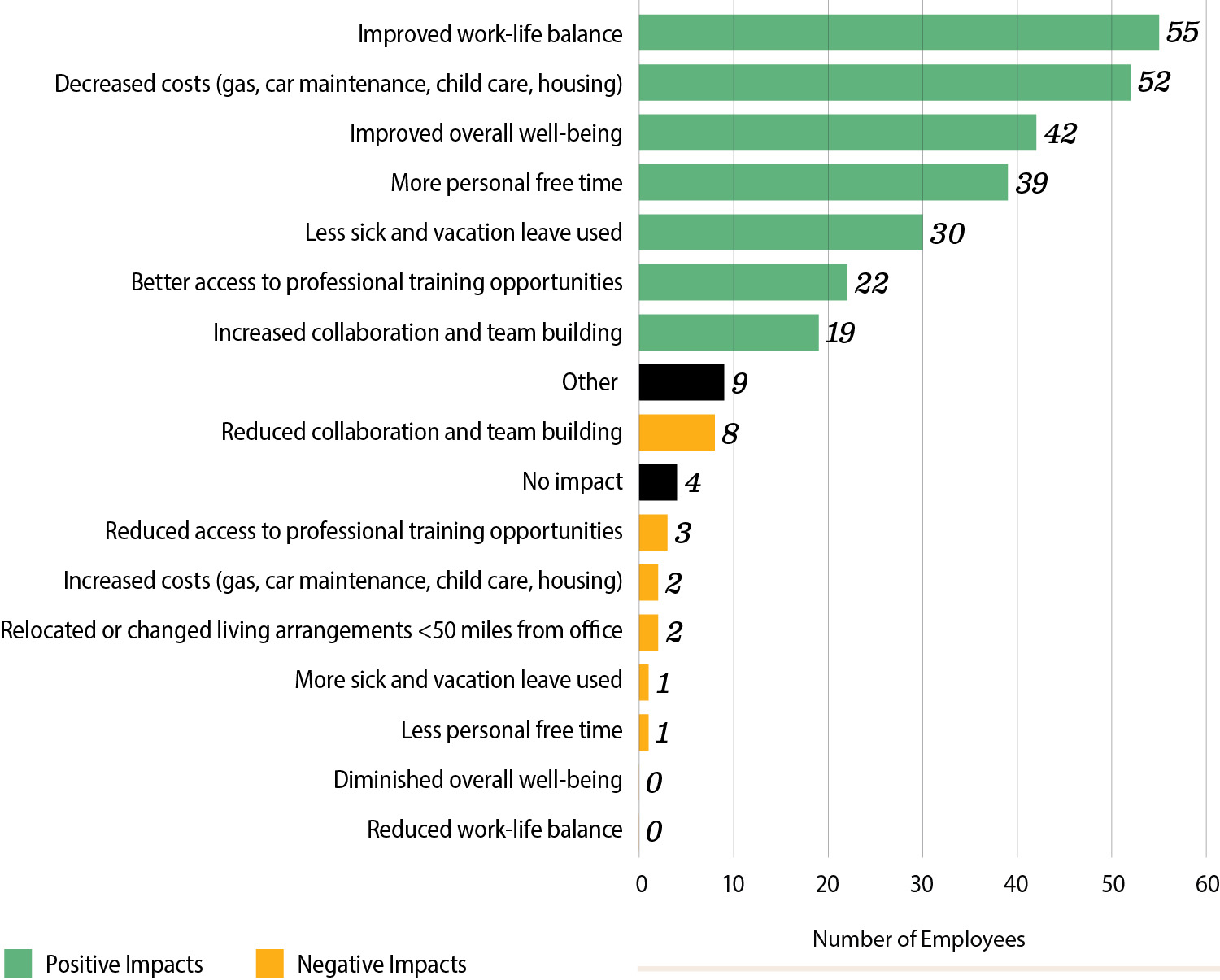

Some state departments’ representatives reported that the departments view telework as a beneficial tool. Employees from CARB, CalPERS, Caltrans, and FTB generally indicated that the implementation of telework improved their work-life balance and overall well-being and decreased their costs. Our department survey results indicated that telework benefited departments by lowering costs, reducing the amount of office space needed, and improving recruitment and retention, without negatively affecting productivity or customer service, as Appendix A shows. For example, 67 percent of responding departments’ representatives reported that the departments experienced improved or unchanged productivity after implementing telework.

To understand whether these departments had the data to support their responses to the survey question about productivity, such as with metrics like cases processed per employee, we asked them how they made this determination. Department representatives who reported improved productivity indicated that they examine productivity through performance reviews, various check-in meetings and staff surveys, and by monitoring the quality and timely completion of staff work and projects. Some department representatives also mentioned that telework introduced the adoption of various technologies or electronic processes, such as using Microsoft Teams, that have improved collaboration and customer service. For example, one department’s representative stated that Microsoft Teams allows the department to collaborate in unique ways and more easily facilitate meetings with customers and stakeholders, leading to improvements in customer service and more efficient use of staff time. The fact that departments’ representatives generally responded to our survey with positive feedback about telework indicates that their telework practices have worked well for the departments, although these indicators of productivity appear to be qualitative rather than quantitative in nature.

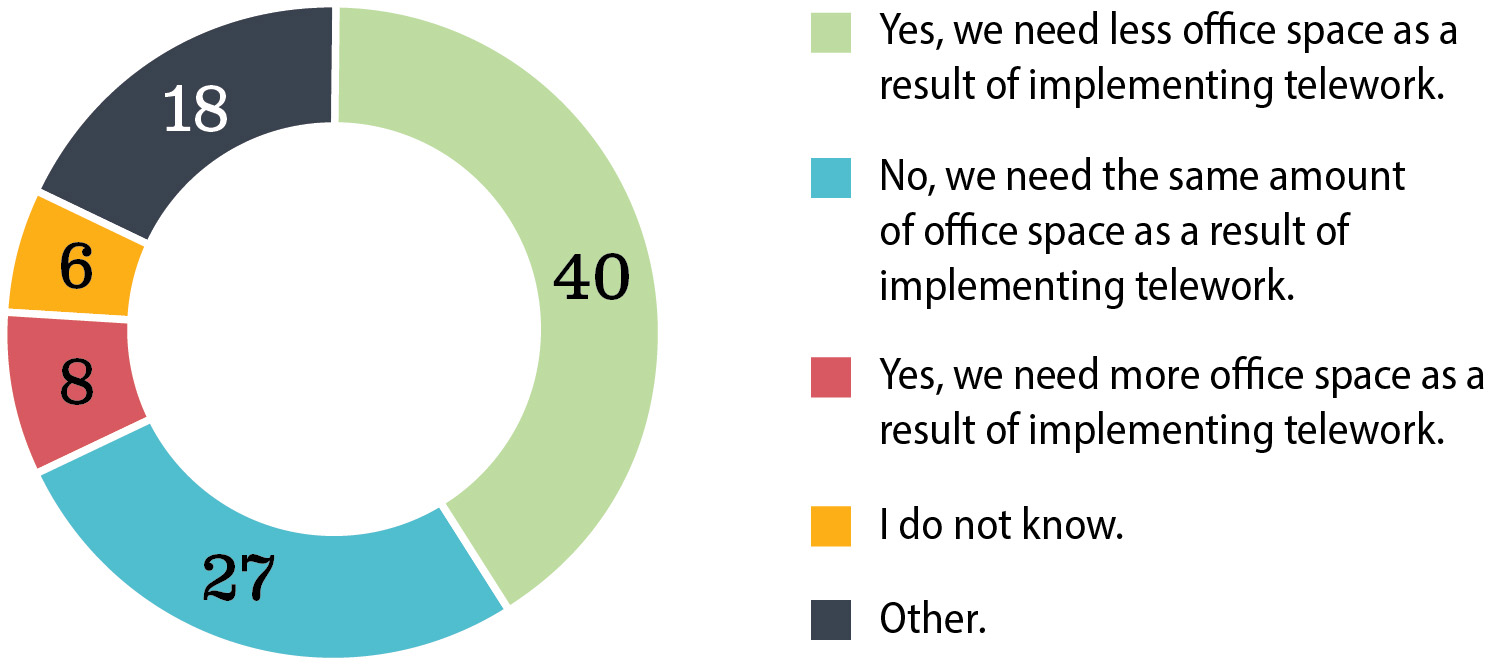

Our employee survey found that managers, supervisors, and staff typically did not report experiencing reduced collaboration because of telework. For example, in response to a multiple-choice question about the impact of telework on their professional lives, 30 percent of respondents reported increased collaboration and team building while teleworking, and just 13 percent reported reduced collaboration and team building following the implementation of telework. One employee explained that they believed collaboration had improved through telework because of the ability to screenshare. In contrast, when asked how the April 2024 directive to return to the office two days per week affected them, just 11 percent of respondents reported increased collaboration and team building. Furthermore, as Figure 2 illustrates, 16 percent reported experiencing reduced collaboration and team building, with some employees noting that collaboration suffered because of misaligned scheduling of in-office days. For example, several employees mentioned that working in the office does not help with collaboration because meetings still occur virtually, people come into the office on different days, or because employees tend to remain in their cubicles. Although the March 2025 executive order seeks to resolve these scheduling issues, our employee survey results suggest that mandating more in-office days per week may negatively affect employees’ productivity and job satisfaction.

Figure 2

Employees of Four Departments Reported That the Return to Office Generally Impacted Their Personal and Professional Lives Negatively

Source: State Auditor’s survey of managers and staff at four departments.

64 staff and managers from CARB, CalPERS, Caltrans, and FTB selected the following responses to the following question in our survey: “how has the 2024 post-Covid return-to-office directive impacted your personal and professional life?

81% reported increased costs in categories such as gas, car maintenance, child care, and housing.

63% reported less personal free time due to commute.

63% reported reduced work-life balance.

58% reported diminished overall well-being.

41% reported more sick and vacation leave being used.

16% reported reduced collaboration and team building.

13% reported reduced access to professional training opportunities.

3% reported that they relocated or changed living circumstances.

16% selected “other” as a response.

14% reported no impact.

11% reported increased collaboration and team building.

3% reported better access to professional training opportunities.

3% reported improved work-life balance.

2% reported decreased costs in categories such as gas, car maintenance, child care, and housing. 2% reported improved overall well-being.

Managers and supervisors were generally more positive than staff about the effect of returning to the office on collaboration and team building, but some also reported a reduction in collaboration and team building. Specifically, slightly more than half of the managers and supervisors who selected collaboration and team building as one of the responses to the question about the impacts of returning to the office indicated that collaboration and team building increased, and just under half noted that it decreased after returning to the office two days per week. Most of the few respondents who reported that telework reduced collaboration and team building were also managers and supervisors.

Our employee survey results regarding productivity and job satisfaction provide important insights into the perspectives of state employees and their managers. For example, two-thirds of respondents reported that their individual productivity improved as a result of telework, commonly attributing this to experiencing fewer distractions or interruptions, working more hours, or having more energy and less stress while teleworking. Similarly, over two-thirds of the responding managers and supervisors reported that the productivity of their divisions or units either increased or did not change while teleworking. In addition, when we asked respondents if they agreed with the requirement to work in the office a minimum of two days per week, more than 80 percent answered that they disagreed with the requirement. Further, nearly half of respondents reported having less job satisfaction since returning to the office. As Figure 2 shows, employees reported that returning to the office affected their lives by increasing personal costs and reducing work-life balance and well‑being and that it resulted in them using more vacation and sick leave. Although our employee survey contains perspectives reported before the Governor issued the March 2025 executive order, the perspectives of these employees provide insight into how that executive order may further affect the personal and professional lives of the State’s workforce.

The results of our surveys demonstrate that telework has provided a variety of benefits to departments and employees. For these reasons, state departments that design telework policies that align with the statewide policy—while still adapting to their unique operational needs—may be in a better position to carry out their programmatic missions and to ensure a satisfied workforce.

Telework Can Generate Significant Savings for the State in Office Costs, Provided That State Employees Telework Three or More Days per Week

Key Points

- Under the Governor’s April 2024 directive requiring state employees to work in the office two days per week, the State occupied more office space than needed. Specifically, we found that the State did not regularly use 3.2 million square feet of office space in the seven state-owned office buildings that we reviewed.

- If state employees telework three or more days per week, DGS has estimated that the State could reduce office space in DGS-managed state-owned and leased buildings by approximately 30 percent, which we estimate could generate cost savings of as much as $225 million annually.

- By requiring employees to work in the office four days per week, which necessitates that each employee has their own dedicated workstation, the Governor’s March 2025 executive order would significantly reduce the possibility of realizing savings from reducing office space square footage and associated costs.

The State Occupied Significantly More Office Space Than It Needed Under Recent Hybrid Telework Arrangements

Telework programs can generate significant savings in office space when entities reduce the number of workstations they must provide. When enough employees telework at least three days per week, or work two days in the office, departments can implement desk-sharing programs that significantly reduce the amount of space they need. Desk-sharing programs sometimes consist of a single workstation assigned to two employees with alternating in-office schedules. In other cases, desk sharing allows employees to reserve a desk from a block of workstations open to all eligible employees on the days that they work in the office. We describe how using less space can lead to cost savings later in this report. The statewide telework policy in SAM states that office-centered employees—those who work in the office more than 50 percent of the week—must have a dedicated workstation in the office. Therefore, because the March 2025 executive order requires most state employees to work in the office at least four days per week, each employee must have a dedicated workstation, and desk-sharing programs are less feasible.

In our review of various reports from other government entities and other research on telework, we did not identify a consensus on how much savings telework programs can produce. Nonetheless, we found guidelines that describe how governments can reduce office space by having employees share desks. Specifically, Oregon’s Department of Administrative Services wrote in its 2024 office utilization and design guidelines that a ratio of one desk for every two employees is appropriate when employees telework three days per week. DGS does not offer similar guidance but agreed with this ratio.6

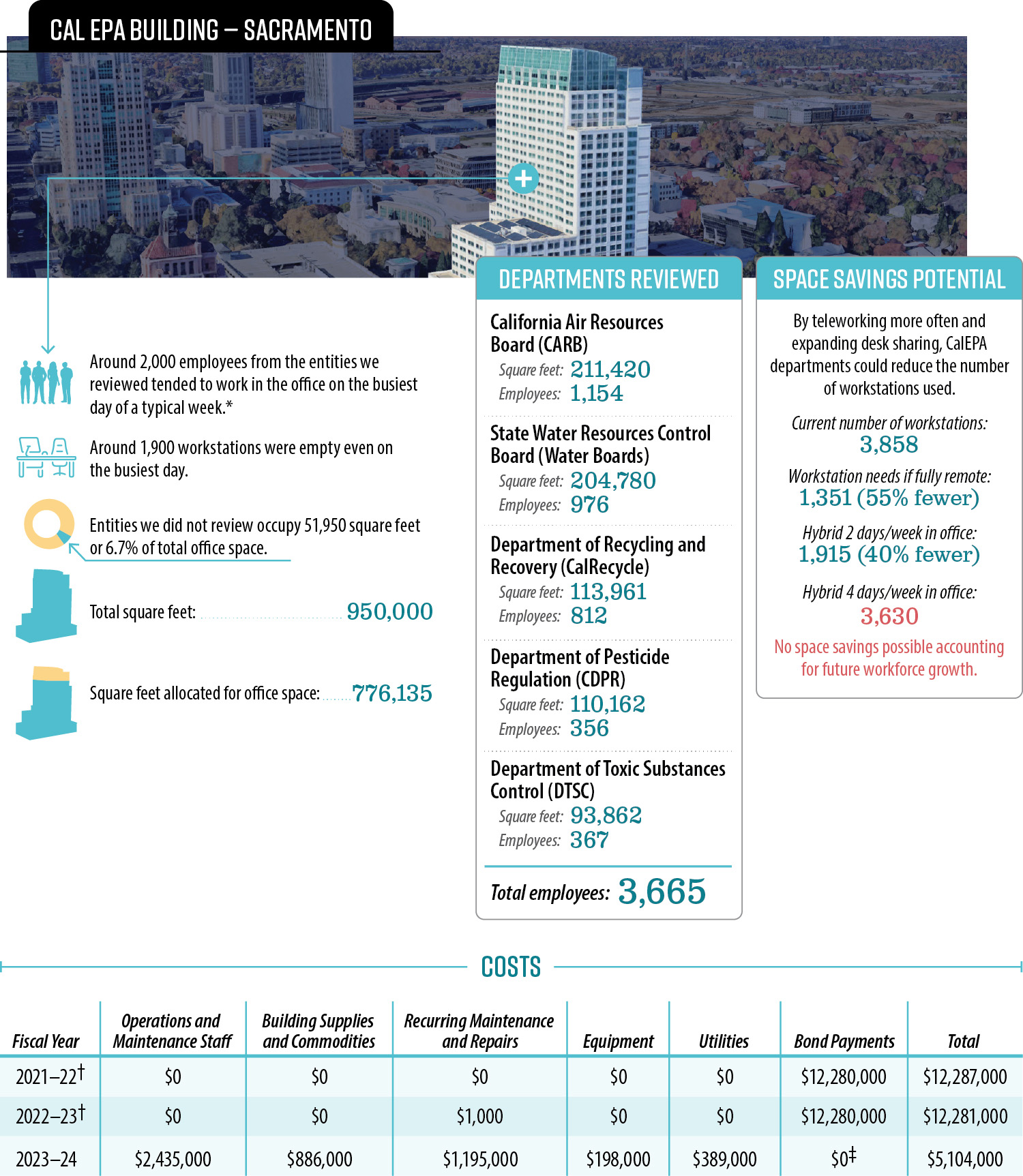

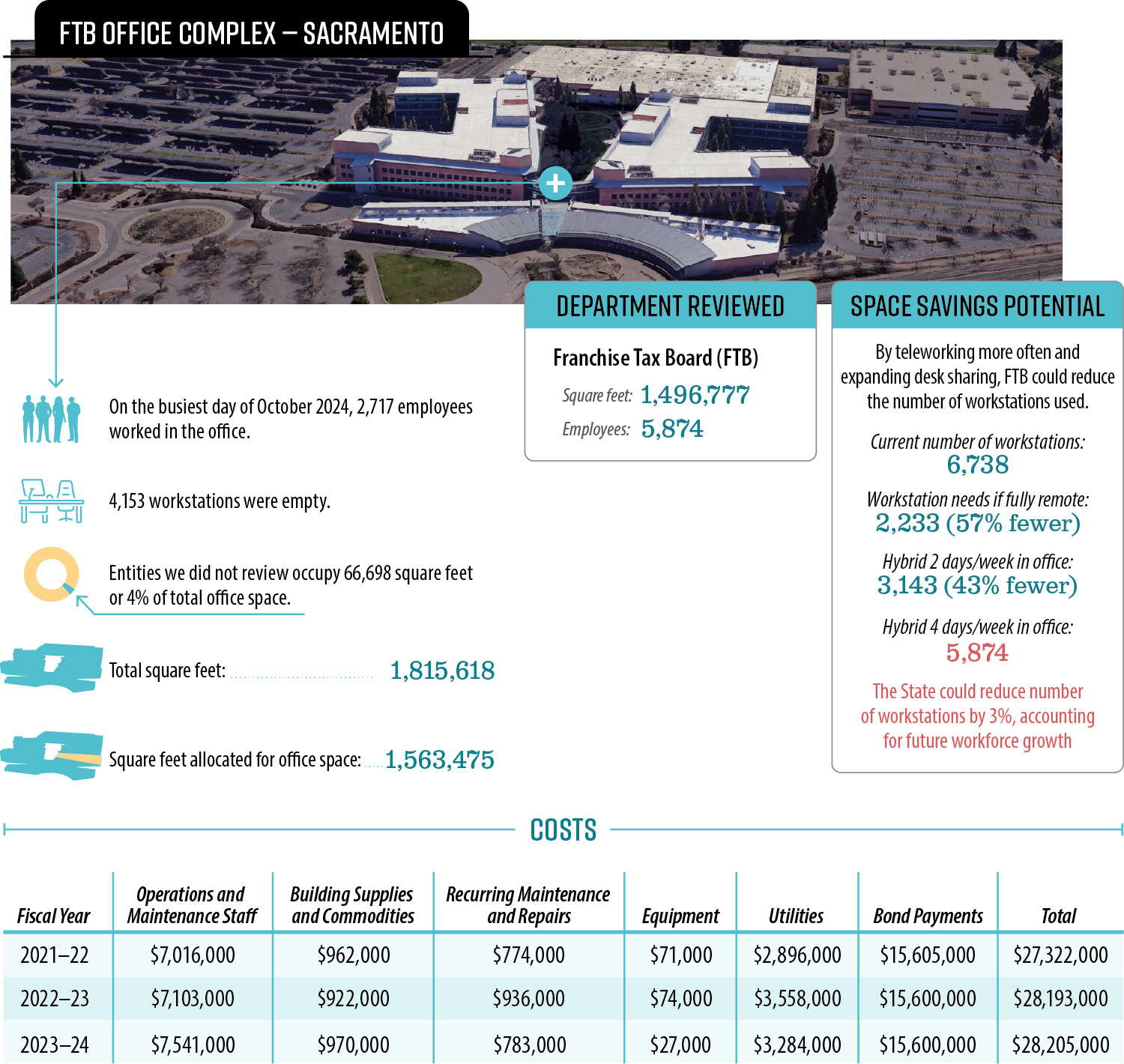

To determine the potential for office space savings in different telework scenarios, we selected seven of the largest state-owned office properties in the DGS real estate portfolio, which we list in the text box, and collected data to determine the total costs to the State for ownership of these buildings from fiscal years 2021–22 through 2023–24. We selected for further review 19 departments that, together, occupied 85 percent of available office space in those buildings. We collected and analyzed employee attendance and office space usage information from these departments to estimate the number of employees working in their offices on the busiest day of a typical week. We also calculated workstation needs according to three different telework scenarios: one in which all telework-eligible employees telework full‑time, one in which telework‑eligible employees work in the office two days per week, and one in which telework-eligible employees work in the office three or more days per week. Appendix C shows the workstation reduction and cost savings estimates from this analysis.

Buildings We Reviewed

Franchise Tax Board Complex (Sacramento)

Capitol Area East End Complex (Sacramento)

May Lee Office Complex (Sacramento)

Ronald Reagan State Building (Los Angeles)

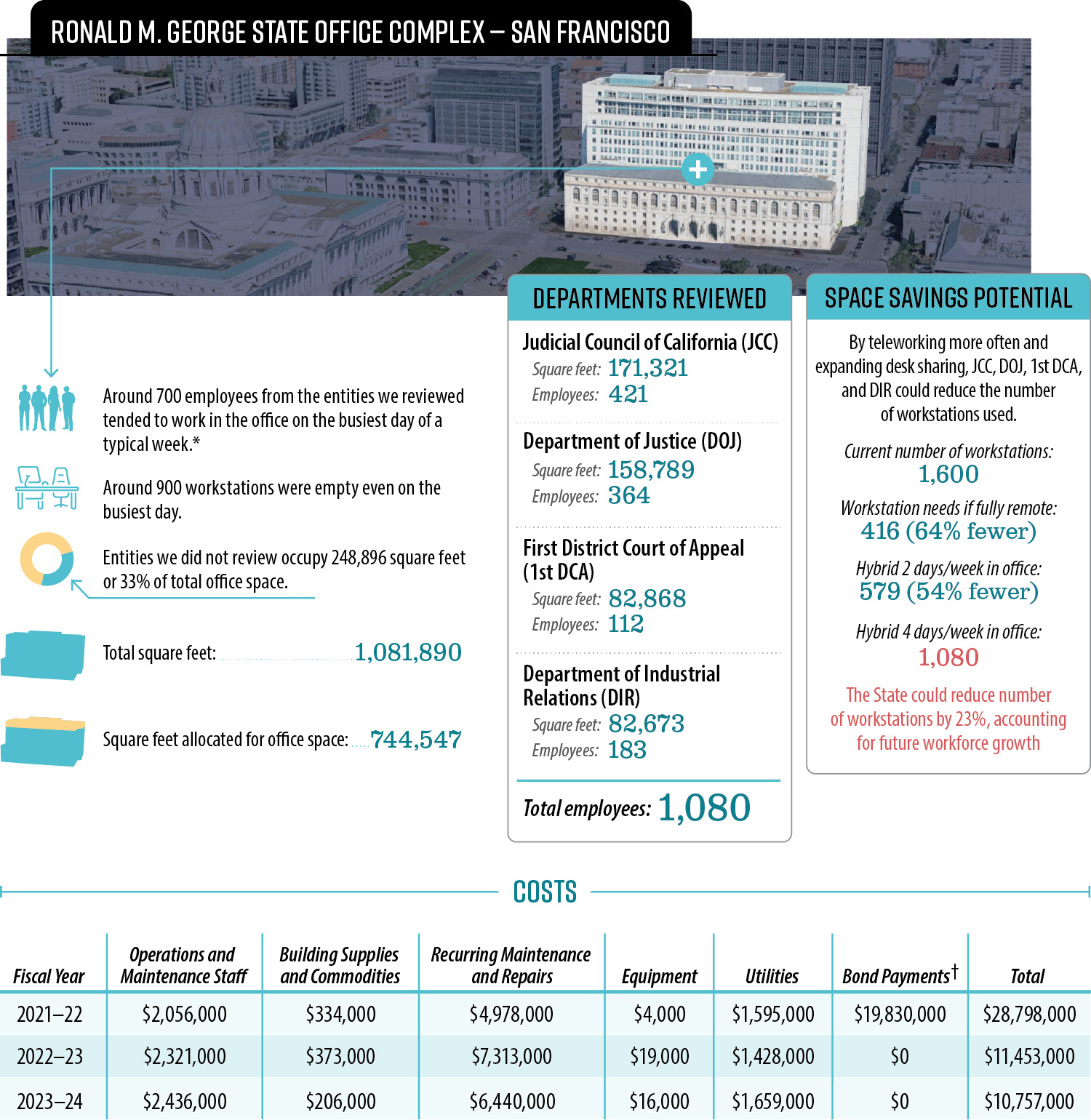

Ronald M. George State Office Complex (San Francisco)

CalEPA Headquarters (Sacramento)

Elihu M. Harris Building (Oakland)

Source: California State Auditor’s Office.

We determined that the state departments we reviewed recently occupied significantly more office space than they needed. We found that during the two-day in-office requirement, 12 of the selected departments used less than half of their workstations on the busiest day of a typical week. Only three departments reported using at least 60 percent of their workstations on the busiest days. Across all seven buildings we reviewed, we estimate that nearly 3.2 million square feet of office space went unused by the 19 selected departments, as Figure 3 shows. This square footage is nearly equivalent to all of the space in the two largest state-owned office properties in the DGS real estate portfolio.

Figure 3

The Departments We Reviewed Spent $117 Million on Unused Office Space in Fiscal Year 2024–25

Source: DGS and other departments’ data.

We reviewed seven large state office properties, totaling 5.5 million square feet of office space used by 19 different departments. We found that these departments used about 42% of this office space and left about 58% unused, totaling 3.2 million square feet. Departments spent about $117 million on this unused office space in fiscal year 2024-25.

To identify the amount that these state departments spent on unused office space, we multiplied the amount of unused space in the buildings we reviewed by the price per square foot of that space. DGS’s chief deputy director agreed that this approach to calculating this estimate was reasonable, with the caveat that it may not be possible for another agency to occupy some unused space. According to this calculation, we estimate that these departments paid almost $117 million to the State in fiscal year 2024–25 for the office space in state buildings that they did not use. Although departments paid this money to the State, these are public funds: To the extent that these departments had reduced their office space and its associated costs, the Legislature could have appropriated those funds to support other valuable public services, such as education or public health programs. Instead, the State spent millions of dollars on office space that often remained unused, and some of that space could have been made available for other departments to use.

If Employees Telework Three or More Days per Week, the State Can Reduce Its Office Space Footprint by 30 Percent

In its February 2025 Real Estate Portfolio Plan, published shortly before the Governor issued his March 2025 executive order requiring state employees to work four days per week in the office, DGS conducted a comparative analysis in which it evaluated multiple in-office scenarios to determine when it was more cost-effective to retain a given building or pursue leasing privately-owned commercial buildings. One scenario it evaluated involved employees teleworking three days per week, or working in the office two days per week, and DGS assumed that this scenario would translate to an approximate 30 percent savings in overall space needs. This 30 percent figure aligns with the goals of other state governments, such as Oregon and Colorado. For California, this 30 percent reduction would amount to savings of more than 10 million square feet of the nearly 34 million square feet of office space that DGS manages. This estimated reduction differs from our estimate of 58 percent of unused space because we looked at specific departments in selected properties, whereas DGS’s estimate is based on its entire office portfolio.

The needs of one of the 19 departments we assessed—the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA)—align with DGS’s 30 percent space savings estimate: With its staff teleworking three days per week, the department no longer needed the use of the more than 714,000 square feet of office space it was initially signed up to lease at the May Lee Office Complex in Sacramento. That office space equated to more than half of the total available space in that complex. In 2021, CDTFA elected to relinquish 141,000 square feet, only ever occupying 573,000 square feet of the buildings. In September 2024, CDTFA requested to vacate an additional six floors in the May Lee Complex, which amounted to 218,000 square feet, or over 38 percent of the department’s remaining office space in the complex. However, after the issuance of the March 2025 executive order, CDTFA reversed this decision and canceled its request to DGS to relinquish these six floors of office space, maintaining its 573,000 square foot footprint. CDTFA’s vacating those six floors could have allowed a new tenant to assume the emptied space, and accommodating more departments in the same amount of space may have allowed the State to save public funds.

Such reductions in office space applied statewide could generate substantial savings. Currently, the State spends approximately $765 million annually on DGS’s portfolio of state-owned properties and leased properties that DGS manages. We estimate that a 30 percent reduction in office space could amount to annual savings of as much as $225 million. DGS’s chief deputy director explained that if the State were to pursue office space reduction on this scale, savings would likely take years to materialize because the State would initially incur some new one-time costs associated with office downsizing efforts. These new costs could include moving costs for departments and renovations to accommodate new tenants.

We expected the departments we reviewed to have pursued reductions of their office spaces in accordance with the statewide telework policy, which expects departments to reduce the amount of required office space and generate savings for the State. From our analysis of workstation usage, we concluded that most departments did not make significant progress toward the goal of office space reduction. At CARB, the division chief of administrative services told us that the department had considered reducing its office space footprint before the April 2024 directive, but the department had since grown reluctant to pursue space savings, in part because of uncertainty about future changes to the State’s telework policy. We acknowledge that there are other substantial obstacles that can complicate or limit a department’s ability to reduce its office space footprint, as we discuss in the next section. However, as a measure of effectiveness, the statewide telework policy expects departments’ telework programs to reduce required office space to generate cost savings.

Reductions in Office Space Are Generally Not Possible When Employees Work in the Office Four Days Per Week

Reduction in the State’s office space footprint can take two forms: consolidating office space or selling the property. Selling the property is called divestment, and Figure 4 presents these processes graphically. Consolidating space involves departments that occupy more office space than they need, reducing the space they occupy and remaining located at the same property. Departments may add shared workstations or increase their use to accommodate the same number of employees in a smaller space. If departments in a building can reduce their occupied space by enough square footage, a new tenant can move into the newly available space that the existing tenants have released. In cases where the new tenant was previously leasing private office space, the State can then exit the lease and generate cost savings. Consolidating space can occur in instances in which a department has leased space that it can vacate or when the department plans to add a significant number of new employees without requiring new office space.

Figure 4

By Consolidating Office Space and Divesting From Office Properties, the State Can Reduce Its Office Footprint and Save Costs

Source: DGS Portfolio Plan and interviews with DGS.

When consolidating office space, a department that has reduced need for space due to increased telework can release office space in their building and allow for a new department to move in to that vacated space, generating savings for the State. In cases where a state-owned property needs to be renovated, if departments relocate to a new location, the State can avoid the renovation and divest from that property, saving renovation costs.

Reduction in the State’s overall office space footprint may also take the form of divestment from state-owned properties. Divestment involves the State either finding a new purpose for a state-owned property, such as use as affordable housing, or selling the property. The departments located in a building slated for divestment would then generally relocate to another property. In its 2025 Portfolio Plan, DGS stated that it had previously presumed that long-term ownership was more cost-effective than continuous leasing, but that its analysis for the 2025 plan ultimately demonstrated that divestment from state-owned office properties and relocation to commercial leases often produces greater cost savings for the State in the long term.

The Ronald Reagan State Building (Reagan Building), built in 1990, is an example of a state-owned office property from which the State could divest to save money. According to DGS, if the State does not divest from the Reagan Building, the State would likely need to renovate it in the future. According to a DGS analysis, such a renovation would take years to complete and would cost the State approximately $660 million in design, permit, inspection, and construction costs. This building is an excellent candidate for divestment if the State largely continues to operate under the April 2024 directive that requires employees to work in the office two days per week. Specifically, we found that over 80 percent of the workstations in the Reagan Building were empty on the busiest day of a typical week under the April 2024 directive. However, the same DGS analysis that identified the Reagan Building as a strong candidate for divestment also found that a full return-to-office policy may require the State to continue owning the building.

Despite opportunities for overall space savings through consolidation and divestment, we recognize that there are significant obstacles to reducing office space. The largest property in the DGS portfolio—the Franchise Tax Board Office Complex—has limited consolidation potential even with a requirement that employees work two days per week in the office, according to FTB’s business and human resources bureau director. Because of the open layout of the buildings in the complex and the need to comply with strict security requirements related to confidential tax documents, FTB asserted that it cannot easily make space available to share with other departments. As the text box shows, there are multiple other challenges that can generally complicate the goal of office space reduction for departments. In ideal circumstances, the newly available space would meet a new tenant’s operational needs without extensive and expensive renovations. Divestment may not be the best option in commercial real estate markets with high lease costs. For example, it may be prudent to rehabilitate an existing state office building if the costs for renovations are lower than the cost to lease other or new office space in that city.

Obstacles for Office Space Reduction

- The need to identify a suitable new tenant.

- Lease terms.

- Moving costs.

- Furniture update or replacement.

- Renovations to meet operational needs of new departments.

- IT costs associated with a new tenant.

Source: DGS Portfolio Plan.

The March 2025 executive order requiring employees to work four days in the office would largely eliminate the potential for telework-related office space savings because it would preclude desk-sharing scenarios and the associated reduction in office space. Under a requirement that employees work four days per week in the office, some departments that previously had a surplus of office space may no longer have enough space to accommodate all employees. For example, we determined that nearly 60 percent of all workstations at the Capitol Area East End Complex were empty on the busiest day of a typical week when the State required employees to work in the office at least two days per week, as Figure 5 shows. Assuming a ratio of one desk for every two employees when they can telework three days per week, we estimate that tenants at this office complex could have reduced their space usage by nearly 2,700 workstations, potentially making available for a new tenant 36 percent of the complex’s square footage.

However, with a requirement that employees work in the office four days per week, these space saving opportunities would no longer exist; instead, the office complex would have more assigned employees than available workstations. Our analysis found that DHCS would need at least an additional 541 workstations to accommodate the employees assigned to the Capitol Area East End Complex to comply with the March 2025 executive order. DHCS may need to obtain additional office space in another state building or through leased private office space to accommodate the March 2025 executive order. The other major tenants at the East End Complex—the California Department of Education and California Department of Public Health—do not face the same challenges as DHCS, but they notably lack room for future growth if their employees were to work in the office four days per week.

Figure 5

The Capitol Area East End Complex May Not Accommodate All Employees Under a Four Day Per Week In‑Office Requirement

Source: DGS, DHCS, CDPH, and CDE data.

* Workstation estimates rely on materials developed by the Oregon state government and assume a 3:1 worker-to-desk ratio for a scenario in which all telework-eligible employees are fully remote, a 2:1 ratio for a two-day in-office requirement, and a 1:1 ratio for a three-day or more in-office requirement. Our estimates also include a 10 percent adjustment for future growth in each department.

† Departments still have workstation needs when all telework-eligible employees work from home because some employees are not eligible for telework and must always work in the office.

The Capitol Area East End Complex May Not Accommodate All Employees under a Four Day Per Week In-Office Requirement.

The East End Complex comprises nearly 1.15 million square feet of office space and we reviewed all but 3% of this space, which is occupied by three major tenants: DHCS, which takes up 465,137 square feet and has 2,715 employees; CDPH, which takes up 369,070 square feet and has 1,935 employees; and CDE, which takes up 284,325 and 1,461 employees.

Around 2,400 employees tended to work in person on the busiest day of a typical week in February 2025, leaving 59% of workstations empty. There are currently 5,833 workstations and 6,111 employees at the East End Complex. Under a hybrid telework policy requiring employees to work in the office two days per week, the State can reduce its space usage by approximately 36%. But under a four days per week in office requirement there would not be enough space to accommodate all employees, with a potential shortage of 278 workstations.

The state spent approximately $40 million annually on the East End Complex in fiscal years 2021-22, 2022-23 and 2023-24, including around $27.6 million in annual bond payments.

Some of the Departments We Reviewed Partially Evaluated Their Telework Programs to Inform Their Past Return-to-Office Decisions

Key Points

- State law requires departments to evaluate their telework programs against criteria that DGS establishes, although DGS has not provided guidance for how state departments should evaluate their telework programs’ performance or effectiveness in meeting goals enumerated in the statewide telework policy.

- We found that only two of the six departments we reviewed used information they collected from employees, such as through employee surveys, to complete partial evaluations of their telework programs and inform their decisions requiring employees to return to the office before 2025.

DGS Has Not Developed Criteria for Departments to Use in Evaluating Their Telework Programs, as State Law Requires

The Audit Committee directed us in May 2024 to determine why DGS, CalHR, and the four additional departments we selected for review made changes to their telework policies. State law requires each state agency to evaluate its telework program against criteria that DGS establishes. Although the statewide telework policy—which DGS developed—does not outline a process for evaluating and determining whether a department’s telework program is effective, the policy does state that an effective telework program must provide a benefit to the State and its employees and be cost neutral or generate savings. It further states that department telework programs are expected to meet the goals we list in the text box. However, DGS has not provided guidance for how state departments should evaluate their telework programs’ performance in meeting these goals. Without such guidance on how to determine the effectiveness of their telework programs, it is not surprising that we found that only some of the six state departments we reviewed partially evaluated whether their telework programs benefit the State and its employees as intended.

Goals of an Effective Telework Program

- Encourage participation of eligible employees.

- Reduce required state office space.

- Improve employee retention and recruitment.

- Maintain or improve employee productivity.

- Reduce state environmental impacts, such as traffic congestion.

- Maintain or improve customer service.

Source: SAM.

Departments Generally Required Employees to Return to the Office to Increase In‑Person Interactions

The six departments we reviewed provided us with various reasons for changes they have made to their telework policies or practices. All but one of these six departments implemented a hybrid return-to-office policy before the Governor’s April 2024 directive, as the text box shows. We reviewed documentation and asked all six departments why they implemented a return-to-office decision, and we found that they primarily based their decisions on intangible factors and external direction. For example, CalHR’s chief deputy director stated that in September 2023, the secretary of CalGovOps verbally directed CalHR and other entities in the agency to require all employees to work two days per week in the office. The departments’ internal correspondence often cited the transition to hybrid telework as a way to increase in‑person collaboration, engagement, employee development, or to preserve department culture. For example, CARB noted in a May 2021 memo to employees that there is value in having direct contact with staff and stakeholders to form relationships and to enhance employee experience and growth by interacting with colleagues and stakeholders.

Timeline of Return-to-Office Decisions for Departments We Reviewed

- CARB: Returned to the office one day per week in July 2021.

- CalPERS: Returned to the office three days per week in March 2022.

- FTB: Returned to the office one day per week in April 2022 and two days per week in October 2022.

- DGS: Returned to the office two days per week in January 2024.

- CalHR: Returned to the office two days per week in January 2024.

- Caltrans: Returned to the office two days per week in June 2024, per the Governor’s April 2024 directive.

Source: Confirmations and documents from departments.

We expected departments to have conducted analyses, such as surveys, before they ordered employees to return to the office, especially because state law requires departments to evaluate their telework programs. Efforts to return employees to the office, which are significant changes for departments with notable impacts on employees and the environment, are an excellent opportunity to evaluate the performance of telework. As a result, we expected departments to base their return‑to‑office decisions on factors such as employee feedback about the successes and challenges of telework, employee performance or well-being, or the delivery of department services in general. Without such valuable information to guide the decision-making process, leaders risk making decisions that may negatively affect their organization, such as by making decisions that lead to reduced job satisfaction, increased attrition, or a reduction in the quality of department services.

Of the six departments we reviewed, only three collected information to better understand the challenges and benefits of telework, and two of those departments used that information to inform decisions related to telework. As Table 1 shows, CARB, FTB, and Caltrans surveyed employees to obtain information about telework in their departments. CARB and FTB reported using the data from their surveys to help inform decisions related to telework. For example, CARB surveyed managers in 2020 and found that they experienced challenges staying connected with colleagues and building relationships and culture with new staff during full-time telework. CARB’s deputy executive officer confirmed that the survey results helped CARB design and implement its hybrid telework program that became effective in July 2021, which required telework-eligible employees to work in the office at least one day per week.

Similarly, FTB’s business and human resources bureau director stated that when considering its return-to-office requirements after the pandemic, FTB incorporated results from its employee experience survey when deciding the number of required days in the office. FTB also conducts a voluntary exit interview process to better understand turnover trends; this data collection found that from February 2024 through January 2025, over a quarter of respondents reported leaving FTB for positions that offered telework options. FTB’s bureau director confirmed that these results partly influenced its decision to implement a two-day in-office requirement instead of a three-day in-office requirement. In contrast, DGS, CalHR, and CalPERS did not formally survey employees about telework or form focus groups to understand its impacts and inform their decision-making related to telework.

Employee responses to our survey show that they appreciated many aspects of teleworking and did not agree with the two-day in-office requirement, an important perspective that state departments could have obtained. Specifically, 81 percent of employees and managers from CARB, CalPERS, Caltrans, and FTB who responded to our survey reported that they did not agree with the two-day in-office requirement. Nearly half reported having less job satisfaction since the implementation of the two-day requirement. Respondents commonly mentioned that teleworking increases their productivity because they experience fewer distractions and less stress and have more energy when working at home. One employee mentioned that although being in the office can support collaboration and team building, they believe that telework practices should be tailored to each agency’s unique needs, rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all approach. This opinion reflects state requirements for tailored telework in SAM, which asks departments to consider the functions appropriate for teleworking and the positions that may be eligible for telework. Employee preferences and satisfaction are only a few of the factors that departmental decision-makers could have considered in evaluating telework policies. However, had all state departments solicited feedback from their staff about returning to the office, the departments likely would have found widespread disagreement with requirements to increase the number of weekly in‑office workdays.

DGS’s Oversight of Telework Policies Was Effective

Key Points

- DGS established a telework program unit (telework unit) in fiscal year 2022–23 to review departments’ telework policies and perform oversight, which led to departments having telework policies that broadly aligned with the statewide telework policy. The unit also collected telework data, such as the carbon emissions avoided when state employees teleworked frequently, which DGS published on a public dashboard.

- In fiscal year 2024–25, the Governor and Legislature eliminated funding that supported DGS’s telework unit. The lack of funding ultimately ended the unit’s work, leaving no designated oversight of the State’s telework programs.

DGS’s Telework Unit Successfully Performed Policy Reviews and Provided Technical Assistance to State Departments

The Audit Committee asked our office to determine the usefulness of the former telework unit for overseeing the State’s telework policy. DGS established its former telework unit in fiscal year 2022–23 to perform telework policy compliance reviews and oversight of state departments. According to a former analyst in the unit, the telework unit’s staff were responsible for reviewing other departments’ telework policies to ensure that they aligned with the statewide telework policy. When those policies did not align, DGS staff provided feedback to departments, who then revised and resubmitted their policies. We reviewed a selection of department telework policies to determine whether those policies complied with the statewide telework policy, which asks departments to establish a written policy specific to the department’s business needs in accordance with the statewide policy and to establish uniform expectations for performance management and communication, and we found that they did. As a result, we determined that DGS’s process for reviewing those policies was reasonable. By December 2022, the telework unit had reviewed 144 department telework policies and found that nearly all of them were compliant, demonstrating a widespread uniformity of telework policies across the state government.

The telework unit helped departments develop their telework policies and manage their telework agreement forms by providing technical assistance and guidance. According to our survey of departments, nearly two-thirds of the 101 responding departments received technical assistance from DGS during the development of their telework policies. The unit also provided technical assistance with telework agreement forms and collaborated with CalHR to offer weekly office hours—which ended in December 2023—to directly support departments. Of the departments we surveyed, 14 percent indicated that they had also requested one-time or ongoing assistance or guidance from DGS after the completion of their new telework policies. DGS noted that questions from departments commonly related to telework stipends, collecting and submitting telework data to DGS, and ways to manage space usage with fewer in-office workers, among other concerns.

In addition to providing guidance and assistance, DGS also created and maintained a public dashboard that reported some of the positive effects of teleworking using data that state departments reported. DGS’s chief information officer explained that DGS launched a telework website in August 2020, offering telework guidelines and a telework dashboard that highlighted DGS’s telework data. He noted that DGS expanded this dashboard in June 2021 by adding telework data from more departments. In October 2021, when DGS published the statewide telework policy, it included in this policy a requirement for departments to report to DGS information related to telework, such as the number of telework-eligible employees and their average number of days working in the office.