2024-107 California Healthy Youth Act

Greater Accountability Would Help Ensure That Districts Comply With All Aspects of the Law

Published: October 28, 2025Report Number: 2024-107

October 28, 2025

2024‑107

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

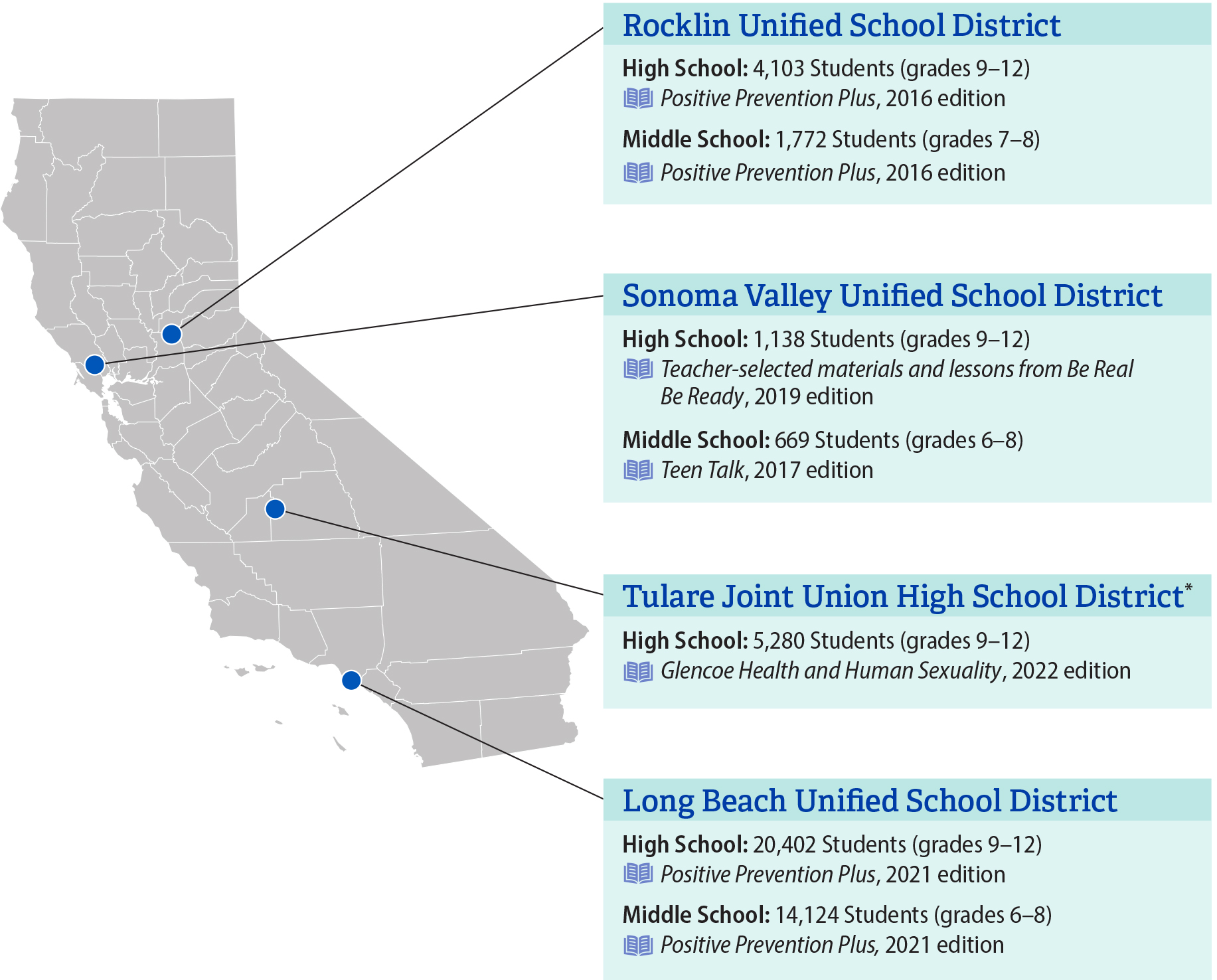

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of a selection of California school districts: Long Beach Unified (Long Beach), Rocklin Unified (Rocklin), Sonoma Valley Unified (Sonoma), and Tulare Joint Union High School (Tulare). Our audit reviewed how well these districts implemented the requirements of the California Healthy Youth Act (CHYA), which requires districts to provide instruction to students on a variety of topics related to sexual health, healthy relationships, and HIV prevention.

In general, we determined that the instructional materials used by these four districts complied with only about 70 percent to 90 percent of CHYA’s content requirements, meaning that students were at risk of not receiving instruction on important topics. Furthermore, teachers at three of these districts modified the instructional materials they were supposed to use in ways that increased their risk of providing noncompliant instruction. For example, one teacher skipped a lesson that included required content about local health resources, and another used alternate materials that did not include any examples of same‑sex relationships. We also evaluated the extent to which districts’ materials included information about LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. Although Tulare’s and Sonoma’s high school materials included less information than the others we reviewed, we found that all districts included information about LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships in their instruction.

In addition, CHYA requires school districts to provide their teachers with regular training. Only Long Beach provided teachers with training, but none of the districts fully satisfied CHYA’s requirements for providing teachers with training on the most recent and medically accurate information related to human sexuality and HIV. We found that districts did comply with CHYA requirements to notify parents about upcoming instruction, as well as their rights to preview instructional materials and opt their students out of CHYA instruction.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CDE | California Department of Education |

| CHKRC | California Healthy Kids Resource Center |

| CHYA | California Healthy Youth Act |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| LACOE | Los Angeles County Office of Education |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (inclusive of other sexual orientations and gender identities) |

| PPP | Positive Prevention Plus |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infection |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The California Healthy Youth Act (CHYA) mandates that school districts provide students with comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education that is medically accurate, objective, and age appropriate. Districts must provide this education to students at least once in middle school or junior high (middle school) and once in high school. The law establishes requirements for the content that teachers must include in their instruction, such as instruction in HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention. The law also establishes requirements for teacher training, notifications to parents and guardians (parents) about instruction, and parental rights to opt students out of the instruction. To conduct this audit, we surveyed school districts throughout the State and reviewed instructional materials and practices at four districts: Long Beach Unified School District (Long Beach), Rocklin Unified School District (Rocklin), Sonoma Valley Unified School District (Sonoma) and Tulare Joint Union High School District (Tulare). We conclude the following:

School Districts’ Instructional Materials Did Not Comply With All of CHYA’s Content Requirements

We found that the instructional materials at the districts we audited complied with about 70 percent to 90 percent of CHYA’s content requirements. For example, the instructional materials often lacked information about sexual assault or about how mobile applications can be used for human trafficking. Additionally, teachers at three of the four districts modified instructional materials in ways that negatively affected the materials’ compliance with CHYA or increased the risk that students would not learn about required topics. As a result, Long Beach high school students may not have received information about local health clinic resources, Rocklin middle school students may not have received information about specific gender‑related topics, and middle school students at Sonoma were not provided instruction on legally available pregnancy outcomes. The Legislature also asked us to review whether districts’ instruction included information about LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. We found the four districts we reviewed all included some related information and that materials from Tulare and Sonoma’s high school contained the least discussion of LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships when compared to the other districts we reviewed.

Districts Did Not Ensure That Teachers Received Training as the Law Requires, but Districts Did Comply With Parental Notification Requirements

CHYA requires that students receive instruction from trained teachers and that districts provide periodic training on new developments in the scientific understanding of HIV. However, none of the four districts could demonstrate that they had provided training sufficient to meet CHYA’s requirements. For example, Long Beach’s training focused more on the format of its instructional materials than on the medical knowledge that teachers may need to accurately instruct students. District administrators at Sonoma and Tulare said that they were unaware of the training requirement, and Rocklin indicated that it trains its teachers on new curriculum only when it updates that curriculum every eight to 10 years. All four districts complied with CHYA’s requirements to notify parents about upcoming instruction and their rights to preview instructional materials and to opt students out of the instruction. The law does not require districts to keep records of how many parents opt their students out of this instruction, and none of the districts we reviewed maintained such records for school years 2021–22 and 2022–23, the period the Legislature asked us to review. However, teachers and administrators told us that few or no parents typically opted students out of instruction each school year.

Increased Guidance and Accountability Measures Would Better Ensure CHYA Compliance Statewide

CHYA does not require ongoing monitoring of school districts’ compliance by any state‑level entity. However, the California Department of Education (CDE) plans to begin monitoring CHYA compliance in the 2025–26 school year. CDE’s monitoring plans represent a positive step toward ensuring that school districts consistently follow CHYA’s requirements. However, CDE’s monitoring is voluntary, and there is no legal requirement for CDE to sustain this oversight in future years. If CDE were to discontinue this oversight measure in the future, students in some districts may not receive the instruction that the Legislature has deemed vital to their sexual health. Further, although the State does not prescribe instructional materials that school districts must use, CDE identified no existing statute that would prohibit it from publishing guidance about materials, such as reviews of specific materials’ compliance with CHYA requirements. If the Legislature directed CDE to publish these types of reviews, school districts could benefit when making decisions about which CHYA instructional materials to use.

To address our findings, we have made recommendations to Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare as necessary to modify their instructional materials so that their materials are compliant with CHYA and update them annually to ensure compliance with changes to the law. We also recommend that districts train their teachers on CHYA‑required topics and track compliance with required training. Furthermore, we recommend ways that the Legislature could ensure that districts are better informed about the compliance of instructional materials and create ongoing monitoring of and accountability for districts’ compliance.

Agency Comments

Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare generally agreed with our recommendations and indicated that they would implement them. CDE provided perspective on two of our recommendations to the Legislature.

Introduction

Background

The California Department of Public Health reports that adolescent sexual health education provides youth with critical skills and knowledge to make healthy decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. In addition, research has shown that comprehensive, medically accurate, and developmentally appropriate sexual health education helps to prevent unintended pregnancy, HIV, and STIs. Effective January 2016, the State adopted CHYA, which mandates that school districts ensure that students receive comprehensive sexual health education and HIV prevention education in specified school grades. The text box shows the three general areas in which CHYA establishes requirements for school districts.

CHYA Includes Requirements in Each of These Areas

- Content: Districts must teach specific information, such as the effectiveness and safety of all FDA‑approved contraceptive methods in preventing pregnancy, and meet general requirements, such as using instruction and materials that are age appropriate.

- Teacher Qualifications: Districts must ensure that teachers are knowledgeable about specific topics and receive periodic training on new developments in the understanding of HIV.

- Parental Rights and Safeguards: Districts must notify parents about CHYA instruction planned for the coming year, notify parents that they can inspect the instructional materials, and advise parents about their right to opt their students out of some or all of the instruction.

Source: CHYA.

Two of CHYA’s purposes are to provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to protect their sexual and reproductive health from HIV, other STIs, and unintended pregnancy and to develop healthy attitudes toward adolescent growth and development, body image, gender, sexual orientation, relationships, marriage, and family. CHYA also aims to promote the understanding of sexuality as a normal part of human development and to ensure that students receive integrated, comprehensive, accurate, and unbiased sexual health and HIV prevention instruction. CHYA exists to provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to have healthy, positive, and safe relationships and behaviors.

To satisfy these purposes, CHYA mandates the topics that districts must include in their instruction. Among these are HIV and STI prevention, contraception and legally available pregnancy options, and relationship and sexual violence. The required topics have changed since CHYA first took effect. For example, the State added topics related to human trafficking and, starting in 2025, expanded the definition of comprehensive sexual health education to include education about menstrual health and added a requirement that districts convey information about domestic violence hotlines.

CHYA requires school districts to ensure that all students in grades 7 through 12 receive comprehensive sexual health education and HIV prevention education at least once in middle school and at least once in high school. In the statewide survey we conducted during this audit, respondents most frequently reported providing CHYA instruction in grades 7, 8, and 9.

CHYA does not establish an oversight mechanism by which the State ensures that school districts comply with its requirements. CDE contracts with the San Joaquin County Office of Education for the operation of the California Healthy Kids Resource Center (CHKRC), which provides access to educational resources, including reviews related to instructional materials for CHYA. According to the information posted to its website, in school year 2020–21 the CHKRC coordinated with reviewers from CDE and the California Department of Public Health, among others, to review instructional materials for alignment and compliance with CHYA. These reviews assessed how well instructional materials aligned with CHYA and noted where publishers could make improvements. The results of these reviews are available online. However, neither the CHKRC nor the State recommends or endorses specific instructional materials to satisfy CHYA’s requirements. Similarly, at the time of our audit, CDE’s website neither provided information about approved or recommended CHYA instructional materials, nor did it indicate that CDE had performed any oversight of districts’ compliance with CHYA.

This Audit Primarily Examines Four School Districts, All of Which Took Similar Approaches to Implementing CHYA

The objectives of this audit required us to conduct in‑depth reviews of the CHYA instructional materials of several districts. In addition to conducting a statewide survey of all relevant school districts, we selected four school districts and reviewed their compliance with CHYA: Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare. We selected these districts because of the size of the student population, location of the school district, and the type of CHYA instructional materials the districts used. Figure 1 identifies location and enrollment information for these districts and presents the selected instructional materials for each district.

Figure 1

2024–25 Enrollment and Instructional Materials for the School Districts We Reviewed

Source: CDE data, records of districts’ boards adopting instructional materials, and auditor review of districts’ instructional materials.

Note: These enrollment data do not include students enrolled at charter schools, which were not within the scope of this audit.

* Tulare is a high school district with no enrollment at middle school grade levels. We included Tulare in our selection to ensure a variety of instructional materials and geographic locations in our review.

Rocklin Unified School District is in Placer County in northern California. Rocklin has 4,103 students in high school, grades 9 through 12, and 1,772 students in middle school, grades 7 through 8. Rocklin uses the 2016 edition of the Positive Prevention Plus instructional materials to teach comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education at both the middle and high school levels.

Sonoma Valley Unified School District is in Sonoma County in the North Bay region of California. Sonoma has 1,138 students in high school, grades 9 through 12, and 669 students in middle school, grades 6 through 8. At the high school level, Sonoma uses teacher-selected materials and the 2019 edition of Be Real Be Ready instructional materials to teach comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education. At the middle school level, Sonoma uses the 2017 edition of Teen Talk.

Tulare Joint Union High School District is in Tulare County in the southern Central Valley of California. Tulare has 5,280 students in high school, grades 9 through 12. Tulare uses the 2022 edition of Glencoe Health and Human Sexuality to teach comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education. Tulare is a high school district with no enrollment at middle school grade levels. We included Tulare in our selection to ensure a variety of instructional materials and geographic locations in our review.

Long Beach Unified School District is located along the south coast of Los Angeles County in California. Long Beach has 20,402 students in high school, grades 9 through 12, and 14,124 students in middle school, grades 6 through 8. Long Beach uses the 2021 edition of the Positive Prevention Plus instructional materials to teach comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education at both the middle and high school levels.

These 2024-25 enrollment data do not include students enrolled at charter schools, which were not within the scope of this audit.

The four districts adopted specific instructional materials to assist them in meeting CHYA’s requirements. In general, the districts reviewed instructional material options for quality and suitability for the district after the State’s adoption of CHYA in 2016 and presented recommended materials to their district boards for approval.1 The districts we reviewed provided CHYA instruction as part of other required coursework in middle school and high school. For example, Rocklin provides CHYA instruction to students as part of its 7th grade science curriculum and a 9th grade health class. Similarly, Sonoma also provides CHYA education in a 7th grade science class and in a 9th grade class on human and social development. Tulare includes CHYA instruction in the health unit of its freshman studies course—a required course for all 9th grade students. Long Beach also generally provides CHYA instruction to middle school students in a 7th grade health course, but it provides instruction to high school students in one of a variety of courses depending on students’ individual schedules. In general, districts provided English learners with instruction in these same classes and stated that they provided students whose individualized education plans placed them in settings other than the mainstream classroom with modified CHYA instruction designed to fit these students’ needs. Instruction at each of these districts generally takes place over the course of two to five weeks at both the middle and high schools.

Audit Results

- School Districts’ Instructional Materials Did Not Comply With All of CHYA’s Content Requirements

- Districts Did Not Ensure That Teachers Received Training as the Law Requires, but Districts Did Comply With Parental Notification Requirements

- Increased Guidance and Accountability Measures Would Better Ensure CHYA Compliance Statewide

School Districts’ Instructional Materials Did Not Comply With All of CHYA’s Content Requirements

Key Points

- The instructional materials used by the four districts we reviewed met about 70 percent to 90 percent of the content requirements established by the California Healthy Youth Act (CHYA). Because these materials were not fully compliant, students at these districts were at a greater risk of missing valuable instruction that could benefit their health and well‑being.

- All four districts addressed topics related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. All districts concentrated their discussion of these topics in lessons dedicated to gender or sexual orientation.

- Some teachers modified instructional materials in a way that negatively affected the materials’ compliance with CHYA or increased the risk that students would not learn about required topics. For example, a teacher at Sonoma Valley Unified School District (Sonoma) largely used her own curated instructional materials, which did not feature examples of same‑sex relationships, instead of the district‑approved materials that did feature such examples.

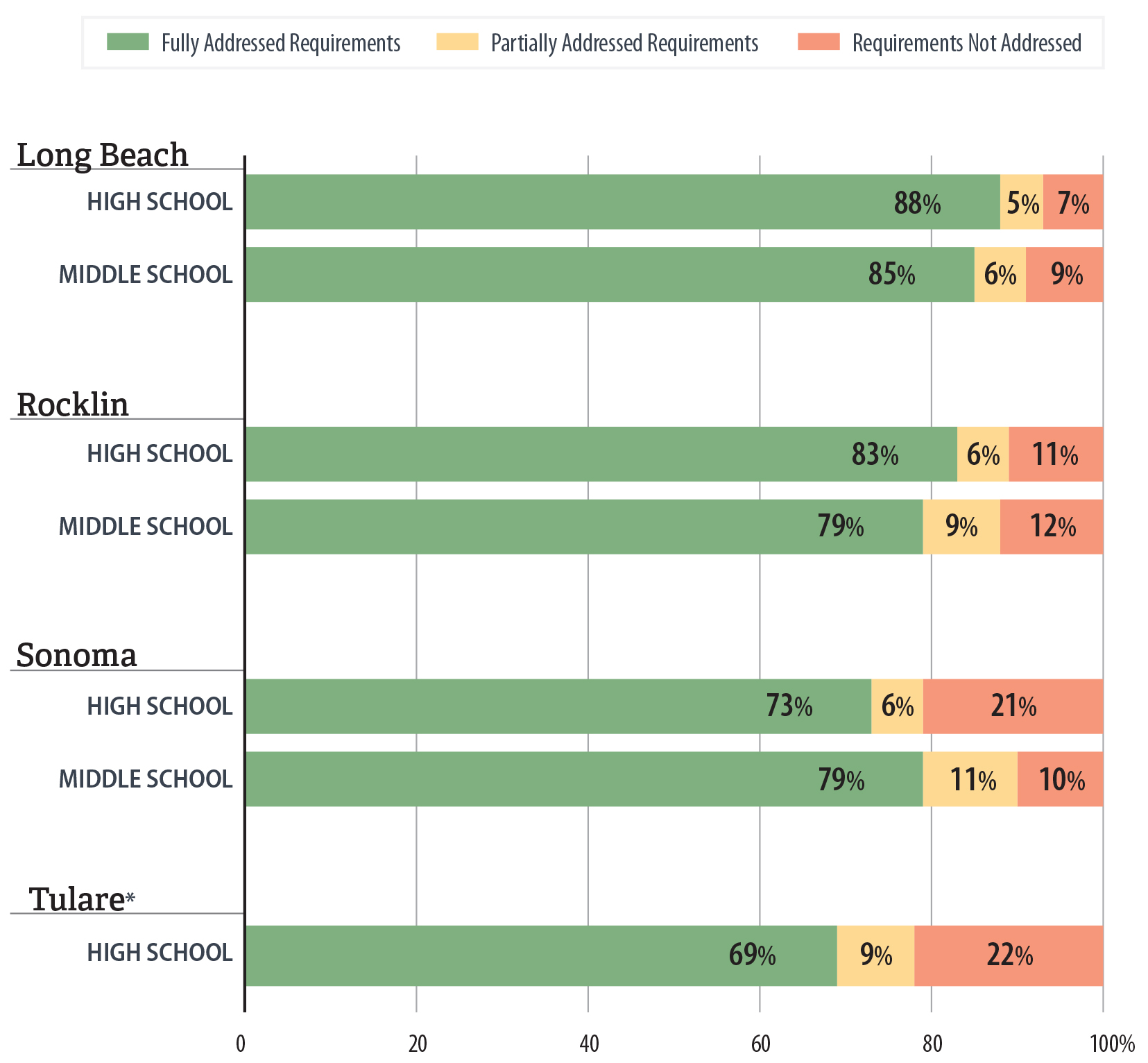

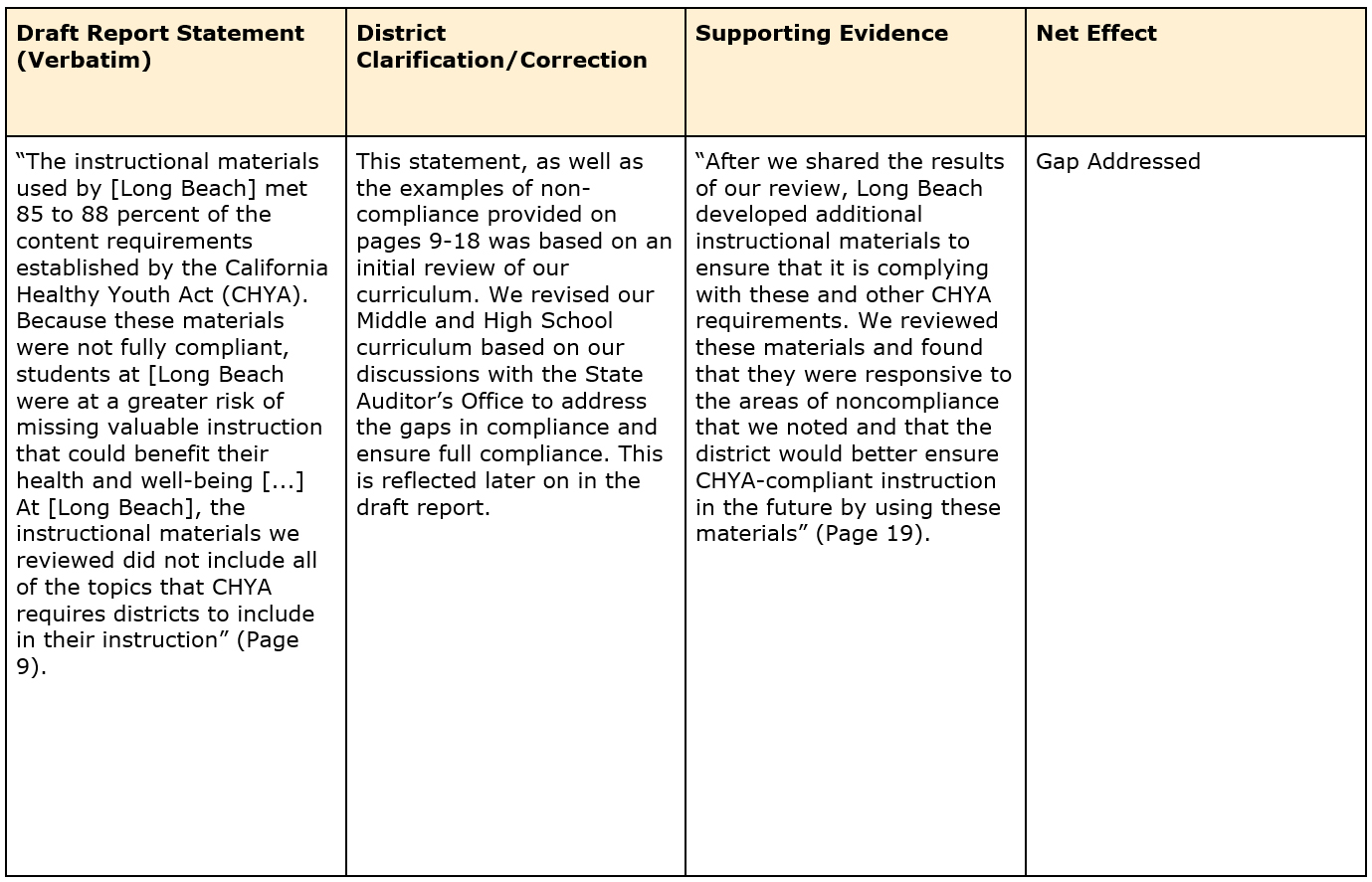

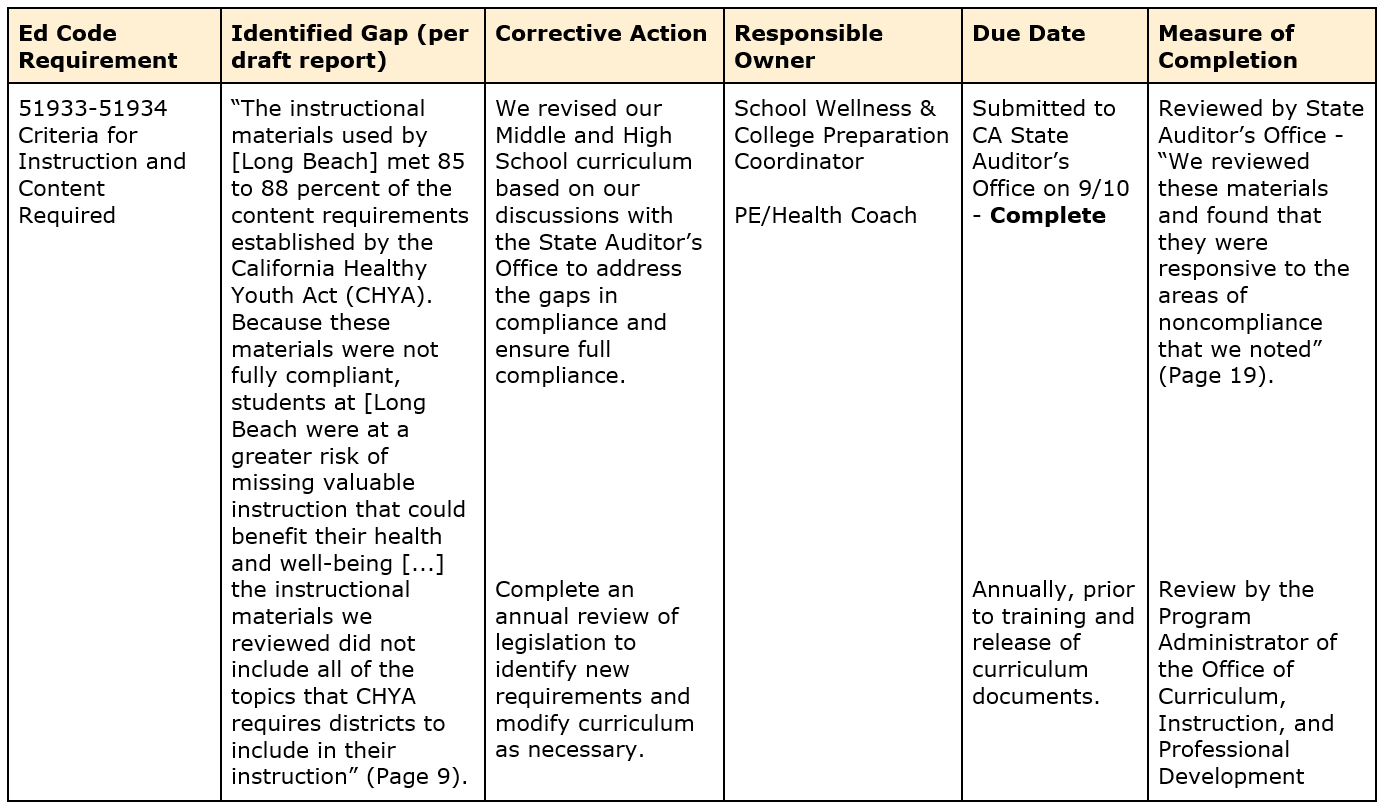

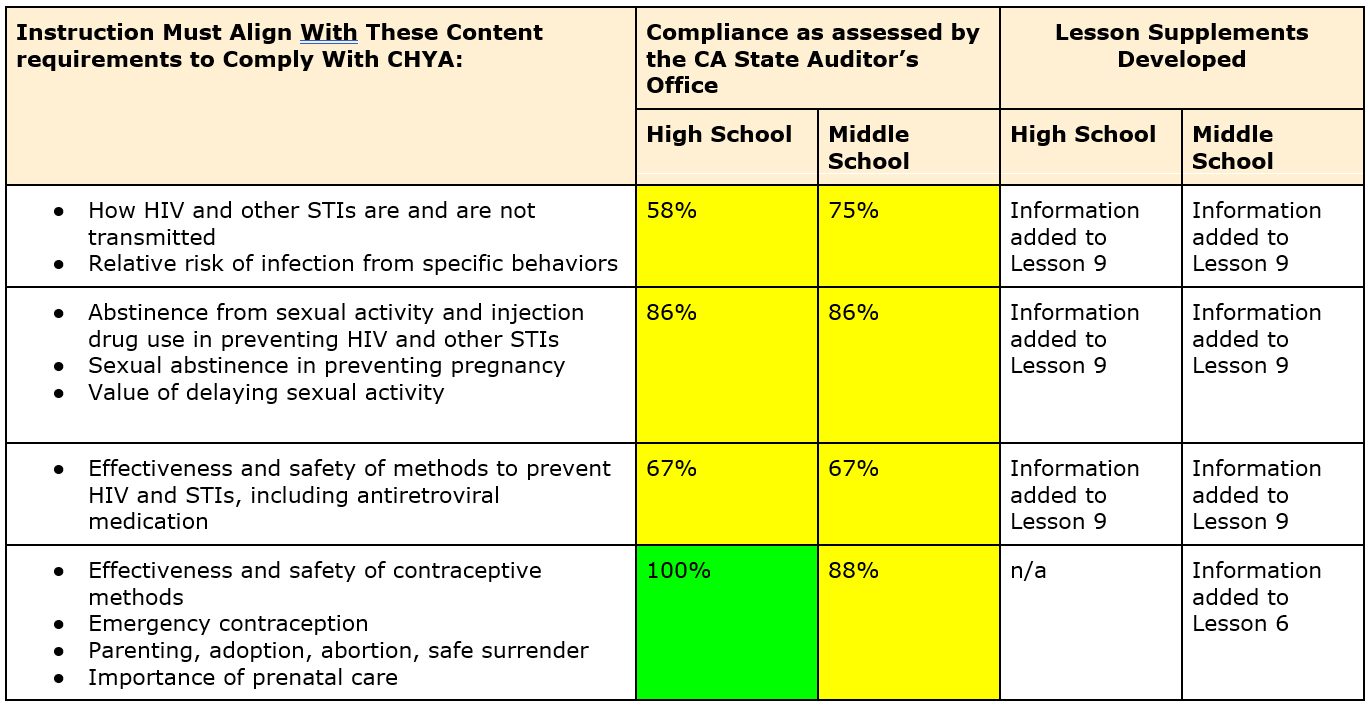

The Instructional Materials We Reviewed Did Not Include All Required Topics

At all four districts we audited, the instructional materials we reviewed did not include all of the topics that CHYA requires districts to include in their instruction.2 To determine the degree to which the districts’ instructional materials complied with CHYA, we reviewed the materials—such as presentation slides or textbook content—that each district had most recently used at the time of our audit. We then compared the information in the materials to 105 different content requirements we identified in CHYA. As Figure 2 shows, the districts we audited used instructional materials that satisfied about 70 percent to 90 percent of the content requirements. Appendix A includes the detailed results of our compliance review.

Figure 2

Districts’ Instructional Materials Did Not Comply With All of CHYA’s Content Requirements

Source: CHYA and instructional materials from the districts.

Note: Figure 5 shows the areas of noncompliance that we found were common across several sets of instructional materials. Refer to Appendix A for detailed information related to our compliance findings.

* Tulare Joint Union High School District does not enroll students in middle school grades.

The figure shows the following CHYA compliance scores for the districts we audited:

Long Beach high school instructional materials fully addressed 88 percent of CHYA requirements, partially addressed 5 percent of the requirements, and did not address 7 percent of the requirements. Long Beach high school had the highest percentage of fully addressed CHYA requirements among the instructional materials we reviewed.

Long Beach middle school instructional materials fully addressed 85 percent of CHYA requirements, partially addressed 6 percent of the requirements, and did not address 9 percent of the requirements. Long Beach middle school had the second highest percentage of fully addressed requirements among the instructional materials we reviewed.

Rocklin high school instructional materials fully addressed 83 percent of CHYA requirements, partially included 6 percent of the requirements, and did not include 11 percent of the requirements.

Rocklin middle school instructional materials fully addressed 79 percent of CHYA requirements, partially included 9 percent of the requirements, and did not include 12 percent of the requirements.

Sonoma high school instructional materials fully addressed 73 percent of CHYA requirements, partially included 6 percent of the requirements, and did not address 21 percent of the requirements. Sonoma high school had the second lowest percentage of fully addressed requirements among the instructional materials we reviewed.

Sonoma middle school instructional materials fully addressed 79 percent of CHYA requirements, partially addressed 11 percent of the requirements, and did not address 10 percent of the requirements.

Tulare high school instructional materials fully addressed 69 percent of CHYA requirements, partially addressed 9 percent of the requirements, and did not address 22 percent of the requirements. Tulare does not have middle schools. Tulare had the lowest percentage of fully included topics among the instructional materials we reviewed.

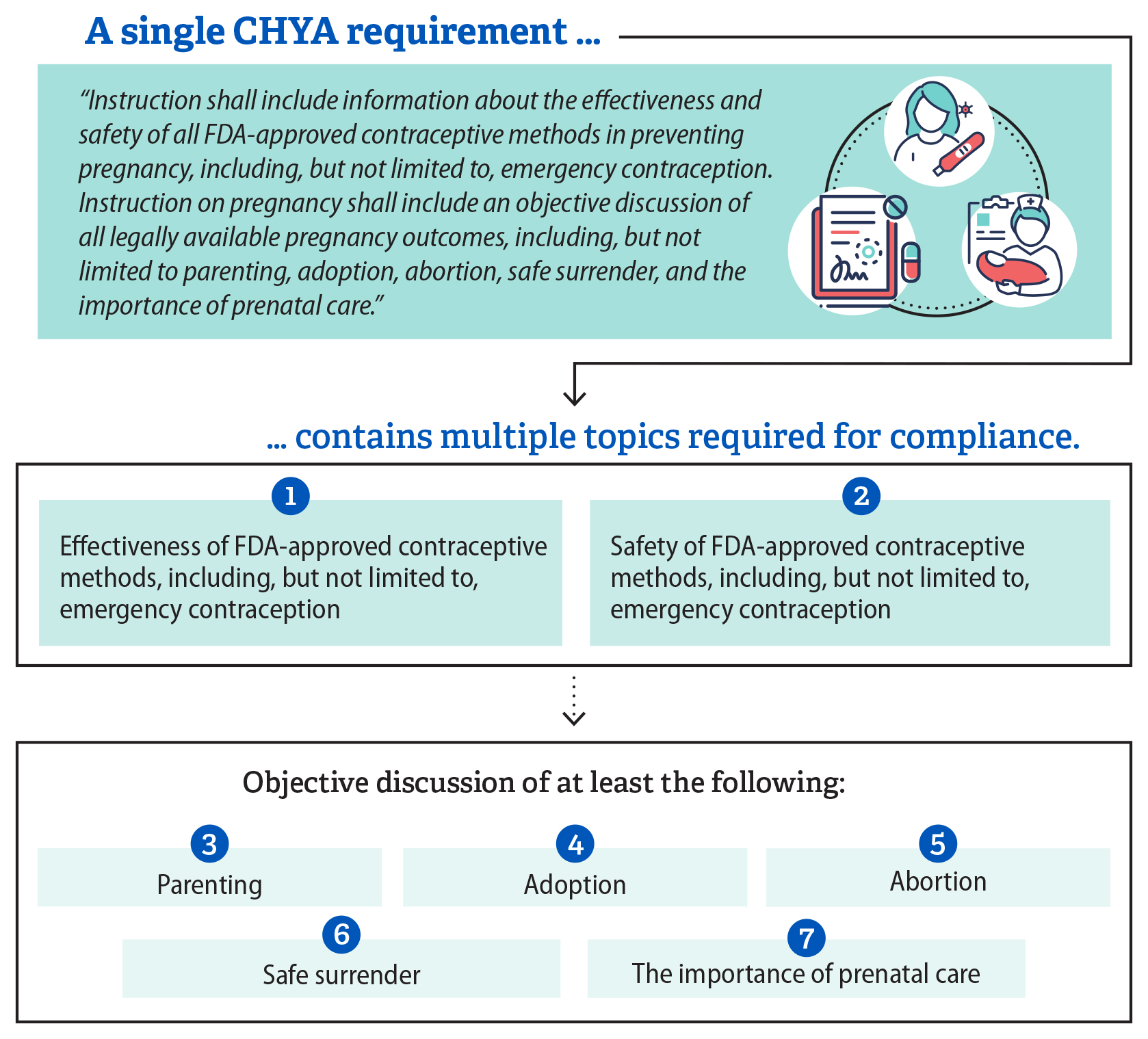

To determine the extent of compliance that Figure 2 shows, we considered CHYA’s content requirements at a detailed level. Figure 3 illustrates how just one section of CHYA can include many topics a district must teach to be fully compliant. In cases where CHYA did not define topics or provide detail about how districts should meet its criteria, we used criteria from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other sources when determining whether instructional materials were compliant. For example, CHYA requires districts to include in their instruction “information about adolescent relationship abuse and intimate partner violence, including the early warning signs thereof.” However, CHYA does not specify what early warning signs districts should teach. In this case, we reviewed instructional materials to see whether they included warning signs of abuse that were published by Love Is Respect, a project of the nonprofit National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Figure 3

CHYA’s Requirements Can Contain Multiple Elements That a District’s Instruction Must Include to Be Fully Compliant

Source: CHYA.

The figure shows an example of one single CHYA requirement: “Instruction shall include information about the effectiveness and safety of all FDA-approved contraceptive methods in preventing pregnancy, including, but not limited to, emergency contraception. Instruction on pregnancy shall include an objective discussion of all legally available pregnancy outcomes, including, but not limited to parenting, adoption, abortion, safe surrender, and the importance of prenatal care.”

The figure then breaks the requirement up into seven different topics to show that all of these are required by the law. The topics are the following:

1. Effectiveness of FDA-approved contraceptive methods, including, but not limited to, emergency contraception

2. Safety of FDA-approved contraceptive methods, including, but not limited to, emergency contraception

3. Parenting

4. Adoption

5. Abortion

6. Safe surrender

7. The importance of prenatal care

We found that there was a set of content requirements—50 out of 105—with which all four districts’ instructional materials complied. For example, all of the materials we reviewed included information about the nature of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and their effects on the human body, which are two CHYA requirements. All materials also encouraged students to communicate with trusted adults about human sexuality, provided information about HIV transmission and treatment, included information about the value of delaying sexual activity, and provided students with knowledge and skills for making and implementing healthy decisions about sexuality.

However, we also found a small number of requirements that all or most of the instructional materials did not address. For example, all materials except for those that Sonoma used at the middle school grade level lacked information about how mobile applications are used for human trafficking. Even the materials Sonoma used only partially addressed this topic. Only the instructional materials from Tulare Joint Union High School District (Tulare) contained information about the safety of all FDA‑approved methods that prevent or reduce the risk of contracting HIV.

In other cases, the districts’ instructional materials only included enough information to partially comply with CHYA’s requirements. For example, as of January 2025, CHYA has required school districts to ensure that their students receive education about menstrual health. Although CHYA does not define menstrual health, when it added the requirement to CHYA, the Legislature recognized the importance of instruction and materials that taught students about the menstrual cycle, premenstrual syndrome and pain management, menstrual hygiene, and menstrual stigma, among other things. Although all district materials we reviewed except Long Beach’s high school level materials discussed either menstruation or the menstrual cycle, none of the districts’ materials addressed the full span of information about menstrual health.

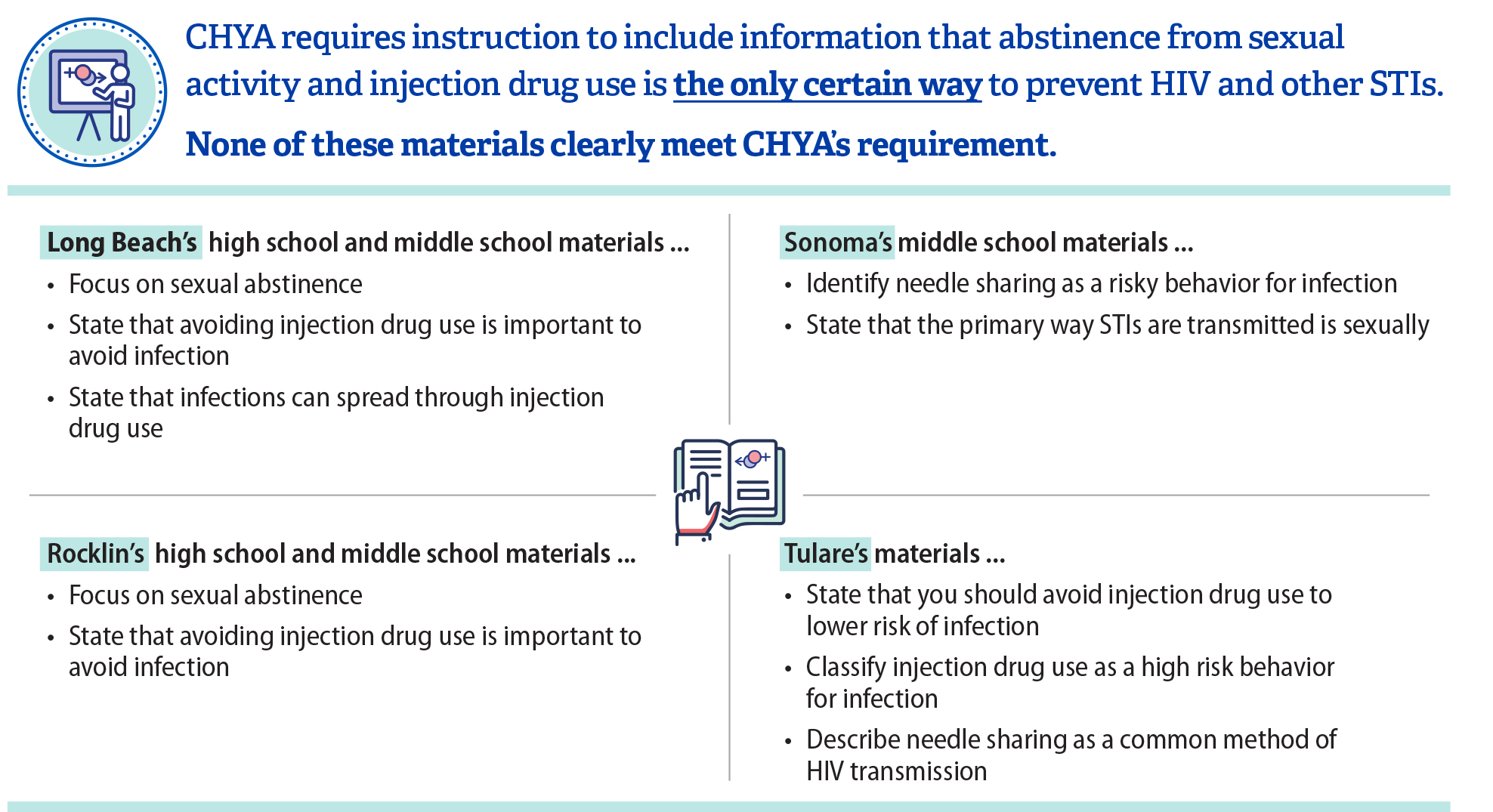

For four of CHYA’s requirements, we found that districts included information that almost addressed a requirement but did not have sufficient detail to comply. Figure 4 provides examples. Also, CHYA requires instruction to include information on how social media and mobile device applications are used for human trafficking. Although materials for Long Beach at both the middle and high school grade levels and Rocklin at the high school grade level included information about the role of the internet in human trafficking, they did not explicitly describe or give examples of how social media sites and mobile applications are used for human trafficking. Consequently, we found these districts’ materials did not comply with CHYA’s requirements, despite having some related content.

Figure 4

Materials From Four Districts Did Not Comply With a CHYA Requirement Despite Offering Related Instruction

Source: CHYA and the materials referenced.

CHYA requires instruction to include information that abstinence from sexual activity and injection drug use is the only certain way to prevent HIV and other STIs.

However, none of the materials described in the graphic clearly met CHYA’s requirement.

Long Beach’shigh school and middle school materials focus on sexual abstinence, state that avoiding injection drug use is important to avoid infection, and state that infections can spread through injection drug use.

Sonoma’s middle school materials identify needle sharing as a risky behavior for infection and state the primary way STIs are transmitted is sexually.

Rocklin’s high school and middle school materials focus on sexual abstinence and state that avoiding injection drug use is important to avoid infection.

Tulare’s materials state you should avoid injection drug use to lower risk of infection, classify injection drug use as a high risk behavior for infection, and describe needle sharing as a common method of HIV transmission.

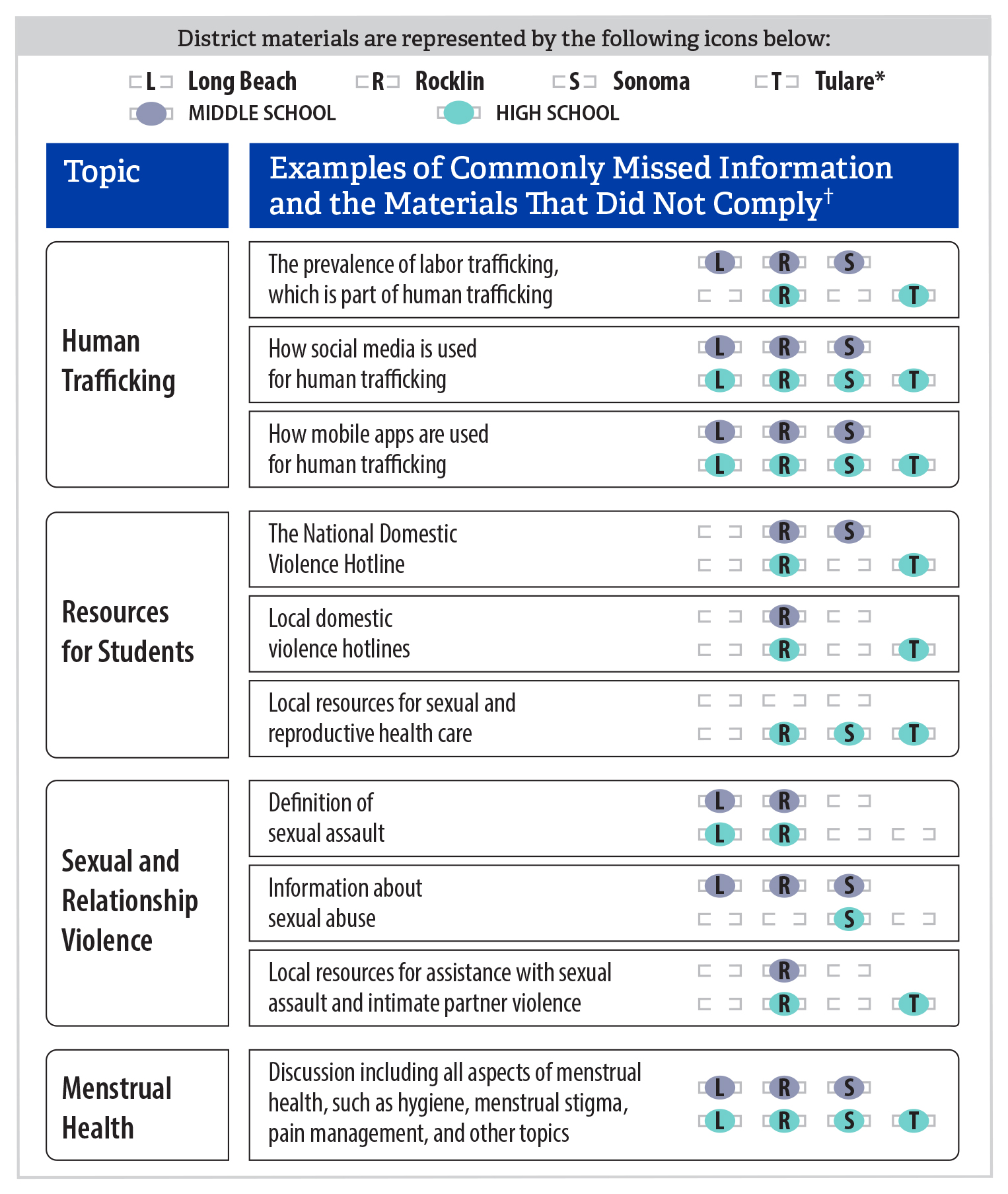

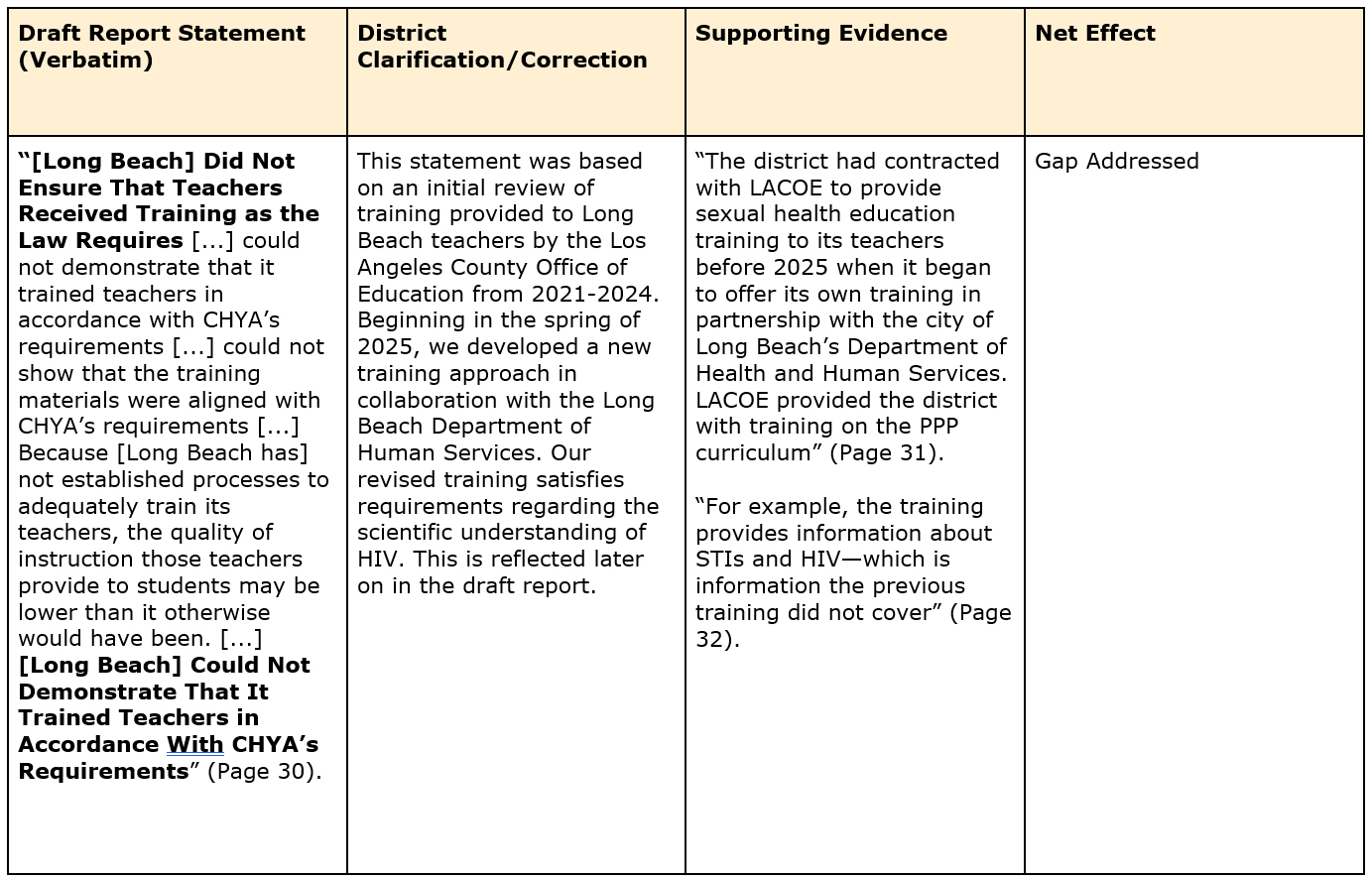

At times, there were similarities to the noncompliance we found. For example, of the middle school level materials we reviewed, none included information on sexual abuse. None of the materials from Long Beach Unified School District (Long Beach) or Rocklin Unified School District (Rocklin) contained information about sexual assault, whereas Sonoma’s and Tulare’s materials addressed that topic. Because the districts’ materials did not always cover required topics, there is a much higher risk that students will not receive instruction relevant to their safety, sexual health, and understanding of healthy relationships. Figure 5 shows the common types of noncompliance we observed in the instructional materials we reviewed.

Figure 5

For Some CHYA‑Required Topics, Instructional Materials Had Similar Gaps in Compliance

Source: Auditor review of CHYA instructional materials.

Note: Compliance with these select topics is not representative of districts’ total compliance with all of CHYA’s requirements.

* Tulare has no middle schools in its district.

† There are generally more requirements related to each topic, but we show a select few requirements with similar noncompliance issues in this figure. This is not an exhaustive list of requirements with which multiple districts did not comply.

The figure gives examples of commonly missed CHYA-required information and the materials that did not comply, grouped by topic area.

Human Trafficking

For the prevalence of labor trafficking, which is part of human trafficking, Long Beach middle school, Rocklin middle school and high school, Sonoma middle school and Tulare materials did not comply.

For how social media is used for human trafficking and how mobile apps are used for human trafficking, none of the materials at Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare complied.

Resources for Students

For the National Domestic Violence Hotline, Rocklin middle school and high school, Sonoma middle school, and Tulare materials did not comply.

For local domestic violence hotlines, Rocklin middle school and high school and Tulare materials did not comply.

For local resources for sexual and reproductive health care, Rocklin high school, Sonoma high school and Tulare materials did not comply.

Sexual and Relationship Violence

For the definition of sexual assault, Long Beach middle and high school and Rocklin middle and high school materials did not comply.

For information about sexual abuse, Long Beach middle school, Rocklin middle school, and Sonoma middle and high school materials did not comply.

For local resources for assistance with sexual assault and intimate partner violence, Rocklin middle and high school and Tulare materials did not comply.

Menstrual Health

For discussion including all aspects of menstrual health, such as hygiene, menstrual stigma, pain management and other topics, none of the materials at Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma or Tulare complied.

There are more requirements related to each general CHYA‑required topic, but we show a select few requirements with similar noncompliance issues in this table. This is not an exhaustive list of requirements with which multiple districts did not comply. Compliance with these select topics is not representative of districts’ total compliance with all of CHYA’s requirements.

In addition, the Legislature asked us to identify whether the districts’ instruction included information about specific topics required by CHYA, such as sexual harassment, sexual assault, and adolescent relationship abuse. Table 1 shows those topics and our conclusions about whether the instructional materials we reviewed contained compliant information about each topic. As the table conveys, districts sometimes lacked sufficient information about sexual assault, adolescent relationship abuse, intimate partner violence, and sex trafficking. Because these are just a subset of CHYA’s requirements, the absence of these specific topics does not necessarily indicate the overall degree to which instructional materials complied with CHYA.

CHYA requires that all instruction and materials align with and support its purposes, one of which is, in part, to ensure that students receive accurate and unbiased instruction. Accordingly, we also reviewed districts’ instructional materials for instances of inaccuracy or bias. Specifically, we judgmentally selected and reviewed five elements of each district’s instructional materials at each grade level. Middle and high school materials at Long Beach and Rocklin, as well as middle school materials from Sonoma each featured statistics that were inaccurate or outdated. For example, Rocklin’s high school and middle school level materials from 2016 used information from the CDC to state that about a quarter of teenagers report using contraceptive methods other than condoms. However, the CDC reported that in 2023, 33 percent of teens reported using hormonal birth control methods before their last sexual intercourse. Accordingly, we determined that these instructional materials only partially complied with CHYA’s goal to ensure that students receive accurate and unbiased instruction. We also determined that Sonoma high school’s materials only partially complied with this goal, as they contained some inaccuracies.

Some instances in the Rocklin and Tulare materials were more significant than others in our review. For example, in a discussion on abortion in Tulare’s textbook, the textbook states that abortion is a surgery that carries the same risk as all surgeries. The text does not mention medication abortion. Because this presentation on abortion incorrectly defines abortion exclusively as a surgery, we believe it is inaccurate. Further, the instructional materials at Rocklin’s high school level and Tulare refer to specific birth control options—intrauterine devices and emergency contraceptives, respectively—as being controversial. These materials do not describe why the birth control options are controversial, and we determined that this content was counter to CHYA’s requirement for unbiased instruction because the information appeared to express an opinion about these options without related medical information, such as information about side effects or risks inherent in using these methods of birth control.

Because we only reviewed instructional materials and not classroom instruction, our testing was limited in its ability to determine actual compliance with the law. Specifically, our testing does not account for how teachers facilitated classroom discussions on CHYA‑required topics. Consequently, there may be instances in which we could not locate information about a required topic in the instructional materials we reviewed, but a teacher may have orally addressed that topic when instructing students.

In fact, teachers and administrators sometimes told us that they addressed required topics, even though their materials did not cover them. For example, a high school teacher at Sonoma said they lead a discussion in their class about myths related to HIV and AIDS, which is a topic that CHYA requires districts to include in their instruction. However, we could not verify that this discussion took place based on the content of their instructional materials. A Tulare administrator also said the district would not expect to find certain topics, such as a discussion of social views on HIV and AIDS, included within its textbook, but would instead expect teachers to lead such a discussion in class. Although a guidance document the district provided establishes key learning objectives that are closely related—such as learning about myths and stereotypes about people infected with HIV—the guide does not direct teachers to lead a discussion on social views. Similarly, we did not identify in Tulare’s instructional materials information about local health care resources. The administrator explained that the district offers students an on-site health clinic at two of its schools, which he was able to substantiate. However, the district could not provide documentation showing that information about these resources was included in its CHYA instruction.

Similarly, our compliance ratings do not account for times when teachers may have omitted required topics that were included in the instructional materials, thereby decreasing compliance. It is possible that even when district resources included CHYA‑required topics, the districts’ teachers did not actually cover those topics when instructing students. We note some instances in which this was the case in our subsequent discussion of modifications.

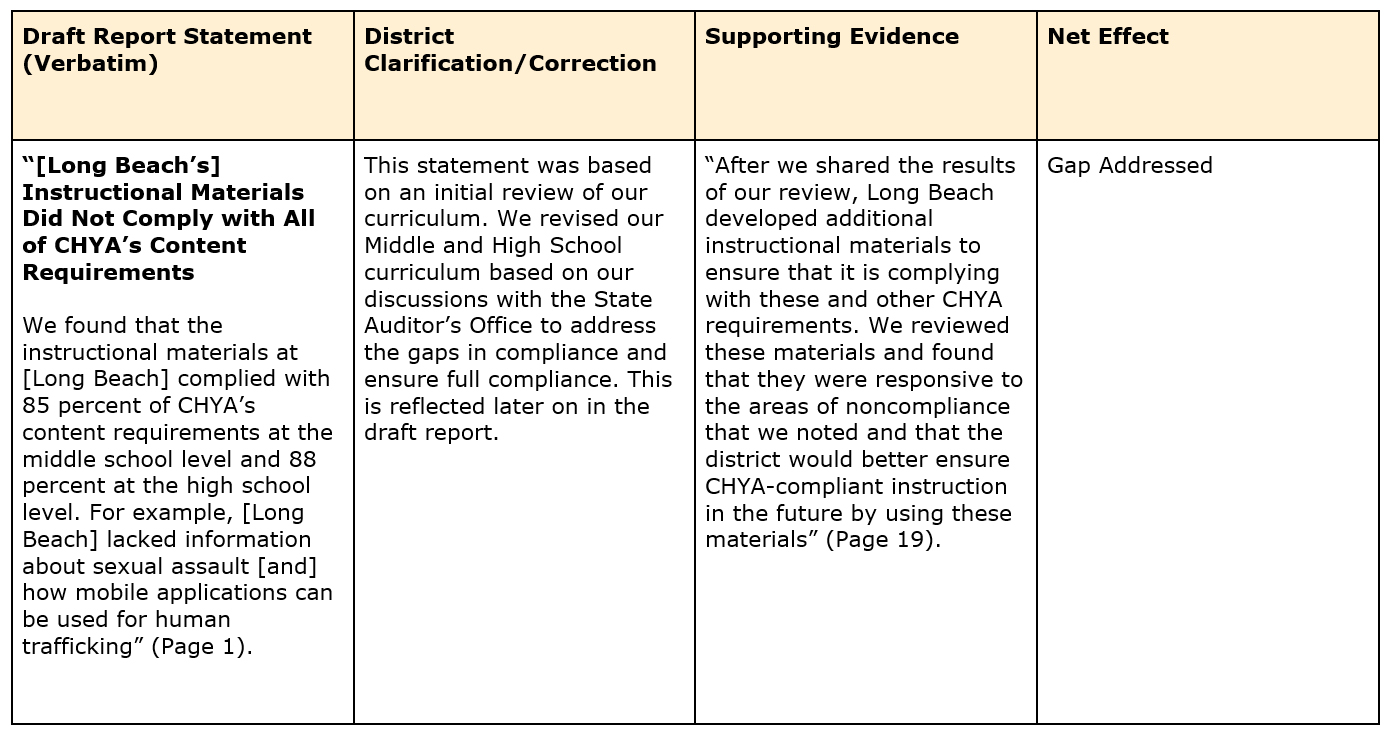

Rocklin generally agreed with our compliance determinations, whereas Long Beach and Tulare indicated that they disagreed with our analysis of their compliance. In response to our request for the district’s perspective, Sonoma did not comment on our compliance determinations. At Long Beach, we neither identified information about sexual abuse in middle school instructional materials nor found information about sexual assault in either the middle school or high school materials. In response to our finding, a Long Beach district administrator highlighted that the district provides resources for how to access services related to sexual assault and abuse as part of its CHYA instruction. Despite the importance of sharing information about these resources, we do not agree that this effort alone satisfies CHYA’s requirement to provide “information about” sexual abuse and sexual assault. We think such instruction would reasonably include a definition of these concepts, which Long Beach’s instructional materials did not provide. After we shared the results of our review, Long Beach developed additional instructional materials to ensure that it complies with these and other CHYA requirements. We reviewed these materials and found that they were responsive to the areas of noncompliance that we noted and that the district would better ensure CHYA‑compliant instruction in the future by using these materials.

Tulare told us that certain lessons in its textbook addressed multiple CHYA‑required topics. However, for most of these topics we either did not find information on the topics in the lessons the district indicated, or we disagreed that the information was sufficient to address the topic. For example, the district told us that it teaches in two specific lessons about the nature and prevalence of human trafficking, how to safely seek assistance, and how social media and mobile applications are used for human trafficking. However, when we reviewed the materials, we found that they focused on violence in families, including spousal abuse and child abuse, or they discussed interpersonal conflicts and types of violence and abuse. We did not find any reference to human trafficking in these materials.

Because of staff turnover, the administrators we spoke with were generally unable to explain why their materials were not fully compliant with CHYA. An administrator at Long Beach said that, although she was not working for the district at the time it selected Positive Prevention Plus (PPP) as instructional material, her understanding was that the district had considered that the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) recommended PPP. At Rocklin, an administrator said he believed the district chose PPP because it perceived PPP as one of the only state‑approved curricula at the time of adoption.3 A Sonoma administrator said that in other cases, their district typically will try to choose curricula that the State has officially adopted. However, the State does not have an approved list of materials. The Sonoma administrator also believed that the district’s curriculum, Teen Talk, is advertised as compliant.

Administrators at the four districts we audited said they typically had not experienced significant barriers when implementing CHYA instruction. Teachers at three of the four districts told us they had difficulty covering all CHYA topics in class given the time allotted to this instruction. Because the scope of our audit did not direct us to review the comparative value of time spent on instructing in one required subject compared to another, we do not reach any determinations in this report about whether the time spent on CHYA instruction should be required to be a specific duration. We similarly asked school districts about challenges to implementing CHYA instruction in our statewide survey. Fifty‑one percent of the respondents reported that they had not encountered barriers to implementation. However, 26 percent of respondents reported negative feedback from the community and parents regarding CHYA instruction as a barrier, and 14 percent listed the cost of developing and purchasing curricula as a barrier, among other challenges.

Districts could improve the accuracy and thoroughness of resources they provide to teachers to support further compliance, as Long Beach recently did. Because CHYA‑required topics were missing from the instructional materials, districts were accepting a higher level of risk that their teachers did not address required content when teaching their class. If districts do not improve their CHYA instructional resources, they will have less assurance that their students are receiving the valuable instruction CHYA requires.

Districts Varied in Their Inclusion of Content Related to LGBTQ+ Bodies and Relationships

As part of this audit, the Legislature asked us to review whether selected school districts’ CHYA instruction includes information about LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. LGBTQ+ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning, and the plus symbol represents inclusivity of other sexual orientations and gender identities. California formally recognizes same‑sex relationships through marriage and domestic partnerships and allows individuals to change birth and marriage records, as well as state‑issued identification cards, to include either the female, male, or nonbinary gender. However, CHYA does not require districts to provide instruction on many topics related to “LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships.” Therefore, to fulfill this audit objective, we consulted other resources, such as those published by public health departments and advocacy groups to identify topics that are related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. As Table 2 shows, CHYA does require that instruction include some content related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships, but there are several other related topics that districts are not required to address.

The topics in Table 2 that CHYA does not require generally align with CHYA’s overall purposes. For example, learning about these topics could help students with LGBTQ+ bodies or who are in LGBTQ+ relationships have the knowledge and skills to have safe and healthy relationships, which is one of CHYA’s purposes. Additionally, such information could provide all participating students with the knowledge and skills they need to develop healthy attitudes regarding adolescent growth and development, body image, gender, sexual orientation, relationships, marriage, and family.

We performed two different reviews of the four districts’ instructional materials to determine how the districts addressed topics related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships—both those that CHYA requires and those we identified in Table 2 as topics not required by CHYA. First, we examined the type and range of topics related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships the districts’ instructional materials covered. Second, we examined the integration of topics related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships throughout the instructional material. We determined whether the materials were addressing topics not only in the sections dedicated to gender identity and sexual orientation but also in sections on puberty and anatomy, family planning and relationships, violence and abuse, reproductive health, and other topics.

Related to the type and range of topics, we determined that the four districts generally covered a common set of topics related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships. When discussing LGBTQ+ bodies, all instructional materials discussed information about intersex bodies and most discussed how LGBTQ+ youth report increased experiences of trauma and related events compared to their straight, cisgender peers, and the materials included examples of LGBTQ+ bodies in relation to common health concerns, such as STIs and unintended pregnancy. Furthermore, most districts’ materials contained definitions and examples of types of LGBTQ+ relationships and included examples of families with LGBTQ+ members.

Conversely, there were several topics that only some of the districts’ materials addressed. For example, only Long Beach’s and Rocklin’s materials included statements about how HIV disproportionately affects gay, bisexual, and other men who reported male‑to‑male sexual contact—which these materials discuss in their units on HIV. In addition, even though the instructional materials at Rocklin defined the term transgender and those at Long Beach explained how transgender individuals may face discrimination, only the high school materials for Sonoma and Tulare contained information about gender transitioning. These details were included in units about gender identity. Nevertheless, we identified the fewest examples of LGBTQ+ content overall in the high school materials for Sonoma and Tulare.

Related to the second factor we considered—the integration of these topics throughout the instructional materials—most of the districts’ instructional materials concentrated the discussion of LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships into units that discussed gender identity and sexual orientation. Tulare’s materials almost exclusively discussed these topics in those units. Long Beach and Rocklin also concentrated most of their discussion of LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships in just one unit of the instructional materials but spread the remaining content across units that covered subjects such as family planning, violence and abuse, and reproductive health. Finally, Sonoma’s middle school materials were the only ones that included a discussion of LGBTQ+ bodies in a unit dedicated to discussing puberty and anatomy.

In addition to the four districts we audited, we reviewed instructional materials from 11 school districts that responded to our statewide survey and determined whether these districts’ materials affirmatively recognized that individuals have different sexual orientations and whether, when providing examples of relationships, the materials provided examples of same‑sex relationships.4 We found that eight of the 11 districts’ instructional materials affirmatively recognized that people have different sexual orientations. Furthermore, we found that seven of the 11 were inclusive of same‑sex couples when discussing or providing examples of relationships.

As we indicate above, the inclusion of more information related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships would support CHYA’s purposes by providing students with further knowledge about how to develop healthy attitudes toward individuals with varied gender identities or sexual orientations and how to develop healthy relationships. Additionally, the results of a recently published study indicate that carefully designed, inclusive comprehensive sexual health education programs reduce beliefs that may lead to bullying, violence, and victimization, and may improve the mental, physical, and sexual health of students by decreasing internalized homophobia and transphobia.5 If the Legislature wants to ensure more comprehensive instruction in information about LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships as part of CHYA, it would likely need to amend CHYA to require districts to cover more specific information and sufficiently integrate the information into the instruction.

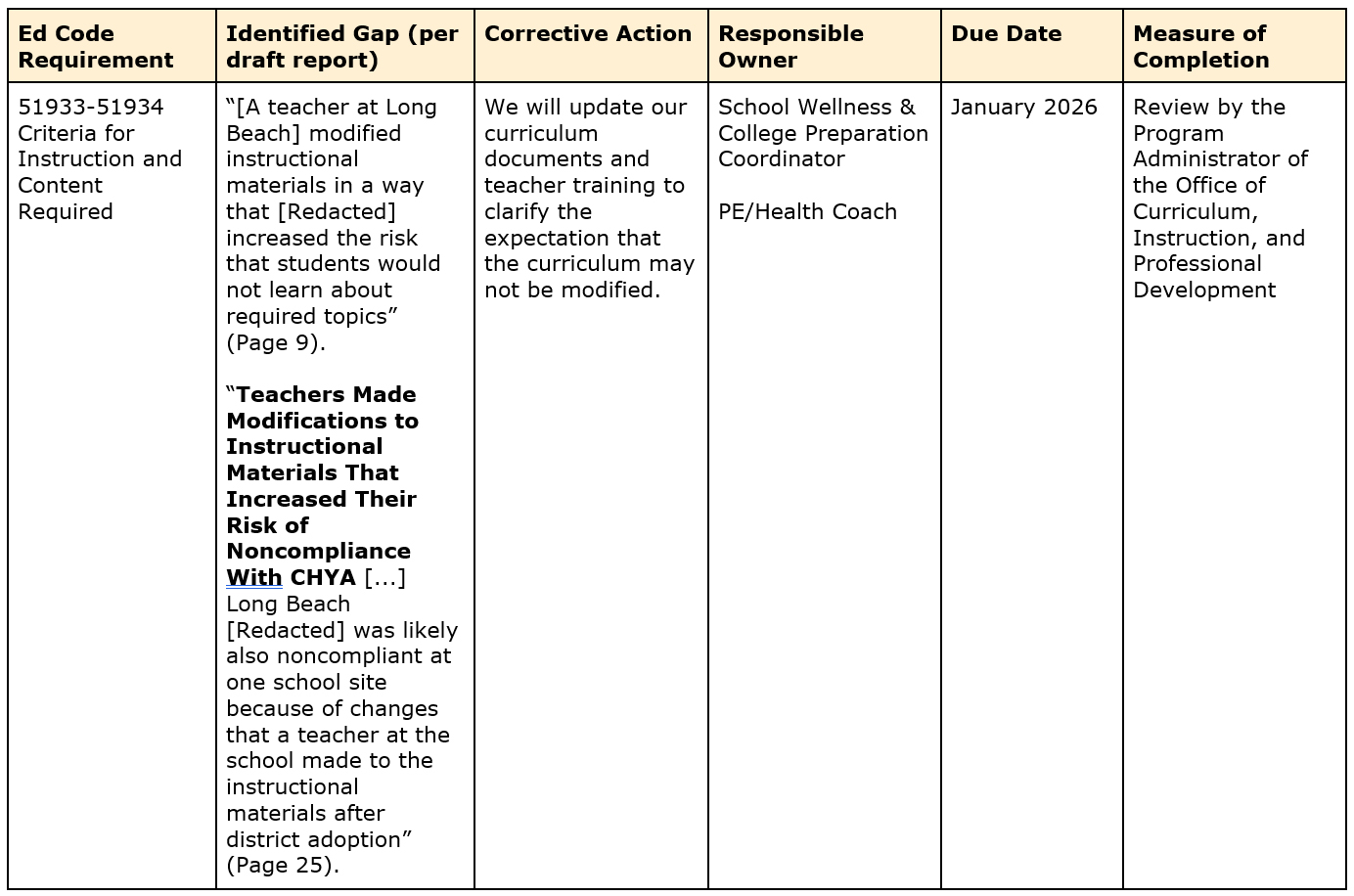

Teachers at Three Districts Made Modifications to Instructional Materials That Increased Their Risk of Noncompliance With CHYA

Beyond the noncompliance in the instructional materials we discuss earlier, the instruction at certain school sites in Long Beach, Rocklin, and Sonoma was likely also noncompliant because of changes that individual teachers made to the instructional materials after district adoption.6 These changes included removing presentation slides, replacing some of the district’s approved materials with other content, or, in some cases, completely omitting lessons from instruction. Only Tulare’s teachers did not make modifications to its materials that affected the district’s compliance with CHYA. Table 3 summarizes the modifications we found and their effects on CHYA compliance.

Districts could reduce the risk that their teachers make modifications to their instruction that negatively affect their compliance by training their teachers about the law’s requirements. CHYA includes training requirements that address how well‑informed teachers are about specific subjects they will teach. For example, CHYA requires districts to provide periodic training to enable school district personnel to learn about new developments in the scientific understanding of HIV, and CHYA also requires teachers to provide instruction about HIV. However, these trainings related to background knowledge would not necessarily educate teachers about the legal requirements for instruction. In other words, teachers can learn about new developments in the scientific understanding of HIV without being informed about the HIV‑related topics the law requires them to teach. Without regular instruction on the law’s requirements, teachers are at a greater risk of altering their instruction in a way that results in noncompliance with CHYA. None of the four districts we audited could demonstrate that they provided training to their teachers regarding CHYA’s requirements before 2025. In 2025, Long Beach began providing training that included content on the requirements of CHYA, although it was unclear from the training materials how all of CHYA’s requirements were explicitly covered in the training. As the results of our audit show, there may be a need for this type of training throughout the State.

Of the districts we reviewed, only Rocklin told us that it had made substantive changes at the district level, meaning that the changes applied to all schools within the district. None of those changes negatively affected the district’s compliance with CHYA. An administrator at Rocklin stated that after adopting the 2016 edition of PPP, Rocklin incorporated an additional lesson on human trafficking. At Rocklin’s high school level, the instructional materials we reviewed included this lesson, which helped the district comply with an update the State made to CHYA, effective January 2018, requiring districts to include information about human trafficking in their instruction. Although the district attested to providing the same human trafficking lesson to the middle schools, we found that the middle schools did not include the lesson in their instructional materials, and therefore the materials did not fully comply with CHYA’s requirement.

Additionally, Rocklin removed two exercises from its instructional materials, one of which asked students to imagine what it would be like to be a different gender, and the other was a live demonstration of proper condom use in the high school materials. Rocklin explained that because of the conservative nature of the district, a previous administrator had decided to remove these exercises in consultation with school staff. We determined that by removing these two exercises, Rocklin did not negatively affect its CHYA compliance because the remaining content in the instructional materials was sufficient to meet CHYA’s gender‑related requirements. Furthermore, CHYA does not require a live condom demonstration, and the materials still covered condom use.

However, an additional change to the instructional materials at one of Rocklin’s middle schools likely reduced compliance with CHYA’s requirements that instruction and materials address specific gender‑related topics. The school’s instructional materials either omitted or included modified versions of several presentation slides from the original materials. These included slides that defined various terms related to gender, such as transgender, as well as images that illustrated the differences between gender expression, gender identity, how these concepts relate to sexual or romantic attraction, and the gender spectrum. As a result of these alterations, the school’s compliance with CHYA requirements about gender expression depended entirely on whether the teacher at the time had provided the correct context to students, either through printed handouts or verbal discussions. A teacher from one of Rocklin’s schools acknowledged making these changes but did not provide a reason why he did so. Rocklin’s associate superintendent informed us that the district was unaware that the school had made these changes. The associate superintendent also acknowledged that the district’s risk of noncompliance with CHYA increases when teachers modify instruction without the district’s approval or knowledge.

Sonoma’s schools made the broadest modifications to the district’s approved materials among the four districts we reviewed. At the district’s only comprehensive high school, the teacher responsible for CHYA instruction used only four of the 26 lessons included in the district’s approved instructional materials. Instead, the teacher relied primarily on materials they selected from a variety of alternative sources because they believe it is important to keep the instruction up to date and that a prepackaged set of instructional materials may become outdated quickly. Because this one teacher taught all high school students receiving CHYA instruction in the district, and because their independently selected content is what students receive in the classroom, we evaluated their materials in the district‑level compliance review we discuss earlier.

This teacher’s instruction would likely have been more compliant had they used the materials the district approved. We found that the district’s approved instructional materials included multiple required topics that the teacher’s materials did not include. For example, we found that Sonoma’s approved materials included information about sexual abuse and provided examples of same‑sex relationships, whereas the teacher’s materials did not include such detail. A district administrator explained that the district allows some flexibility in supplementing instructional materials, but in this instance there was an over‑emphasis on supplemental material, and the district expected its approved materials to be the primary instructional materials. The district informed us that it intends to review our report with the high school teacher and to create a plan to ensure that the noncompliance we found is corrected.

At the Sonoma middle school we reviewed, one teacher supplemented the district’s instructional materials. The district’s copy of its middle school instructional materials did not include content related to adolescent relationship abuse, intimate partner violence, or the warning signs thereof, which are all topics CHYA requires districts to include in their instruction.7 Accordingly, when we evaluated the district’s compliance, we noted that the district did not address these topics. The district’s materials also only partially included instruction on the knowledge and skills students need to form healthy relationships based on mutual respect and affection, which CHYA also requires. However, we did note that, as part of their instruction, this middle school teacher used informational videos about healthy and toxic relationships and consent. Because the teacher used videos that at least partially covered required topics, they increased the school’s compliance with CHYA.

However, that same teacher also informed us that because of time constraints, they did not teach three lessons from the district’s approved instructional materials. These omitted lessons included instruction on legally available pregnancy options and sexual assault, both of which are topics CHYA requires districts to include in their instruction. Because the teacher excluded these topics from instruction, their instruction did not comply with CHYA’s requirements in these areas, resulting in additional noncompliance to the already existing ways in which the district’s materials did not comply with CHYA. As a result, students did not receive information about two important topics and therefore may be less prepared to navigate related real‑life situations in which they may find themselves. When we asked the district about this teacher’s modified approach, a district administrator told us that the district expected teachers to use the district’s approved instructional materials to teach required topics.

We identified a modification at a high school in Long Beach that may have affected compliance. At this high school, a teacher said that she understood two lessons in the district’s approved curriculum to be optional. She did not teach those two lessons and described that she experiences time constraints when teaching the curriculum. One of these lessons emphasized that the only way to know whether someone is infected with HIV is to get tested—a required CHYA topic. Teaching that same lesson would also have prompted the teacher to provide local health clinic information and thereby fulfill a separate CHYA requirement to provide students with information about accessing local resources for sexual and reproductive health care. Because the teacher excluded this lesson, her instruction may not have complied with these two specific CHYA requirements. When we asked the district about this exclusion, a district administrator stated that it is the district’s expectation that teachers cover this lesson, that the district plans to reiterate that expectation in upcoming training, and that it has provided teachers with a list of community resources meant to support this lesson.

Further, at a Long Beach middle school, we identified a modification that reduced the number of examples of same‑sex relationships the instruction featured. When discussing or providing examples of relationships and couples, CHYA requires districts’ instruction and materials to include same‑sex relationships. A teacher at one of the district’s middle schools reported not showing several of the videos included in the district‑approved materials because she believed the style of the videos was ineffective at connecting with students. One of the videos she omitted contained an example of a same‑sex relationship. However, the instructional materials also contained other examples of same‑sex relationships and therefore the instructional materials overall were compliant with CHYA’s requirement.

As we describe throughout this section, the changes Long Beach, Rocklin, and Sonoma made to their instructional materials were not the result of formal processes we could review, but were instead the result of ad-hoc decisions to make adjustments. Although teachers in Tulare also made modifications to their materials, such as using additional instructional slides with students, those changes did not negatively affect compliance because the slides were supplementary to the district’s approved materials. Regardless, these changes were also not the result of a formal process we could review. As we previously discuss, training teachers about the law’s requirements would improve their awareness about what topics they must cover and reduce the risk that their students may not receive all of the knowledge CHYA is designed to deliver.

Recommendations

Legislature

If the Legislature wants greater consistency in CHYA instruction related to LGBTQ+ bodies and relationships, it should amend CHYA to require districts to include more specific information and to integrate the information throughout instruction and materials.

To increase the likelihood that teachers provide instruction that complies with CHYA, the Legislature should amend CHYA to require teachers to receive regular training on CHYA’s requirements and the scope of what must be covered.

Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare

To improve compliance with CHYA, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare should perform a detailed review of CHYA’s requirements and amend or supplement their instructional materials so that they address all required topics. Further, Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare should each annually review the information in their instructional materials to ensure that it is accurate, up‑to‑date, and complies with any changes to state law.

Districts Did Not Ensure That Teachers Received Training as the Law Requires, but Districts Did Comply With Parental

Notification Requirements

Key Points

- None of the districts we audited could demonstrate that they trained teachers in accordance with CHYA’s requirements. Long Beach provides training but could not show that the training materials aligned with CHYA’s requirements. Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare have not established regular CHYA training. Because the districts have not established processes to adequately train their teachers, the quality of instruction those teachers provide to students may be lower than it otherwise would have been.

- Each of the four districts we reviewed notified parents about upcoming CHYA instruction, the parents’ ability to preview instructional materials, and their right to opt their students out of the instruction. The Legislature asked us to calculate various statistics regarding participation in CHYA instruction, but CHYA does not require districts to maintain such records, and districts generally did not track the information that would allow us to address these questions.

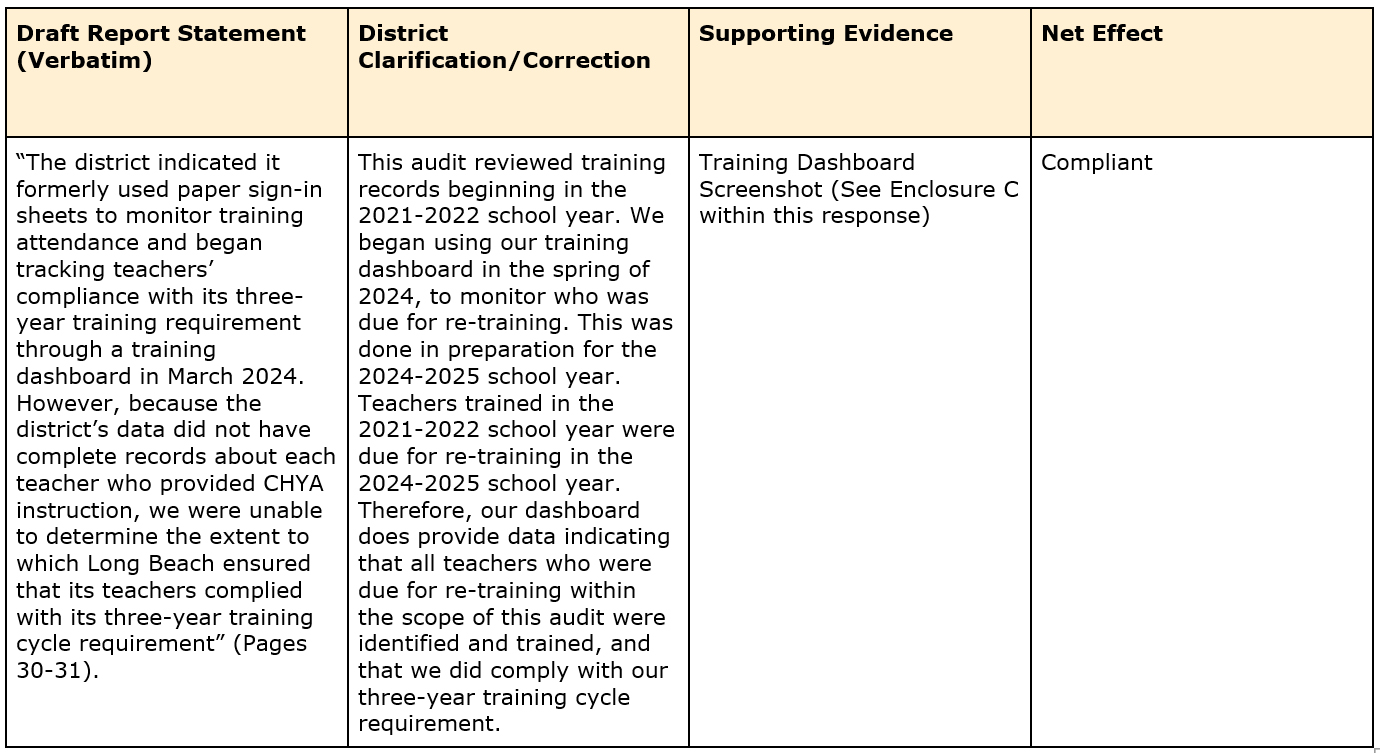

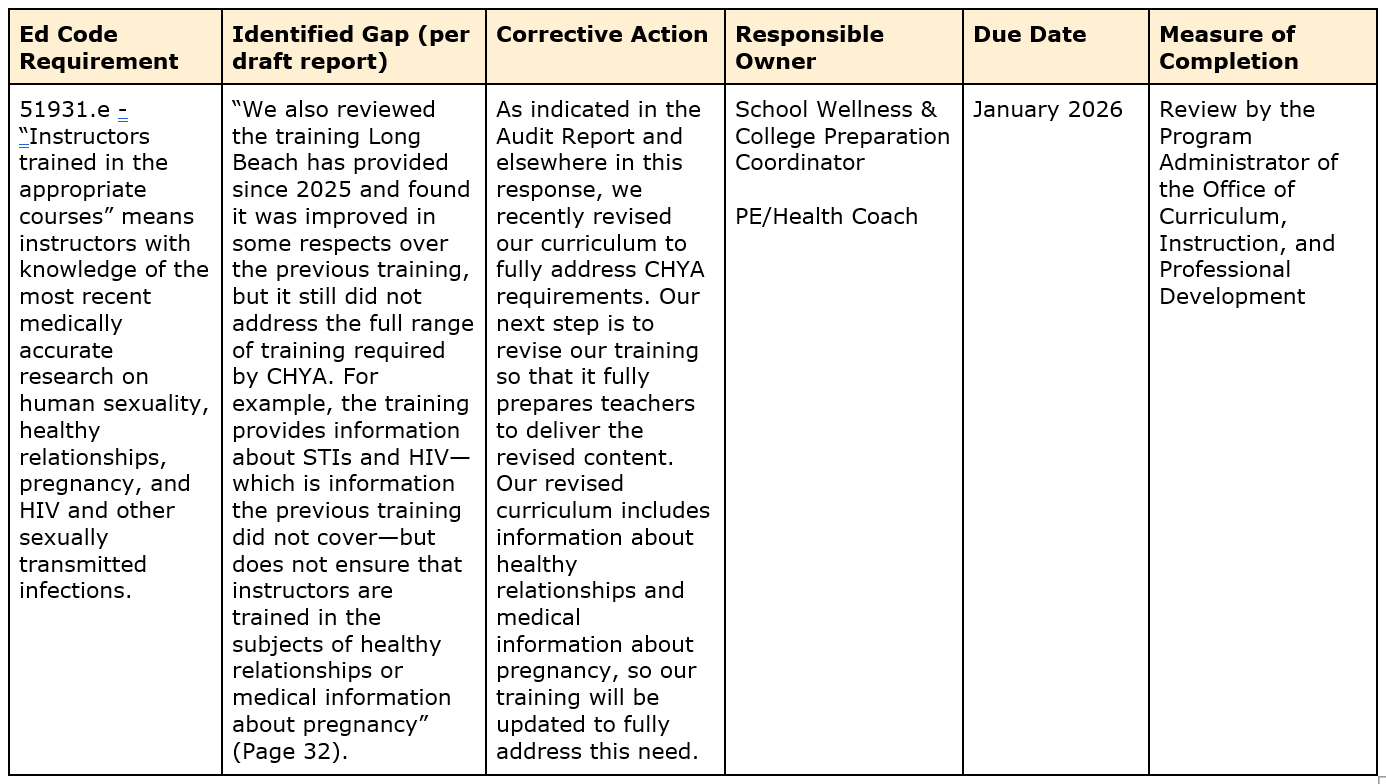

None of the Districts We Audited Could Demonstrate That They Trained Teachers in Accordance With CHYA’s Requirements

To comply with CHYA, districts must ensure that the individuals providing instruction have up‑to‑date information on specific topics about which they will teach. CHYA establishes two training requirements. First, CHYA requires districts to ensure that students receive instruction from teachers trained in the appropriate courses, which it defines as those with knowledge of the most recent medically accurate research on specified topics that the text box shows. To satisfy this CHYA requirement, districts must also periodically provide teachers with training about new developments in the understanding of abuse—including sexual abuse—and human trafficking, as well as current prevention efforts and methods. CHYA does not define how often teachers should receive training to meet this requirement. Second, CHYA requires districts to provide periodic training to enable school district personnel to learn about new developments in the scientific understanding of HIV. However, the law does not set specific intervals for this periodic training. Because both requirements aim to ensure that teachers are aware of new or updated information, we determined that to meet CHYA’s requirements, districts would need to ensure that teachers receive training at some regular frequency. Therefore, we refer to these two requirements as regular training.

Training for CHYA Teachers

CHYA‑compliant teachers are knowledgeable about the most recent, medically accurate research on the following topics:

- Human sexuality

- Healthy relationships

- Pregnancy

- HIV and other STIs

Source: CHYA.

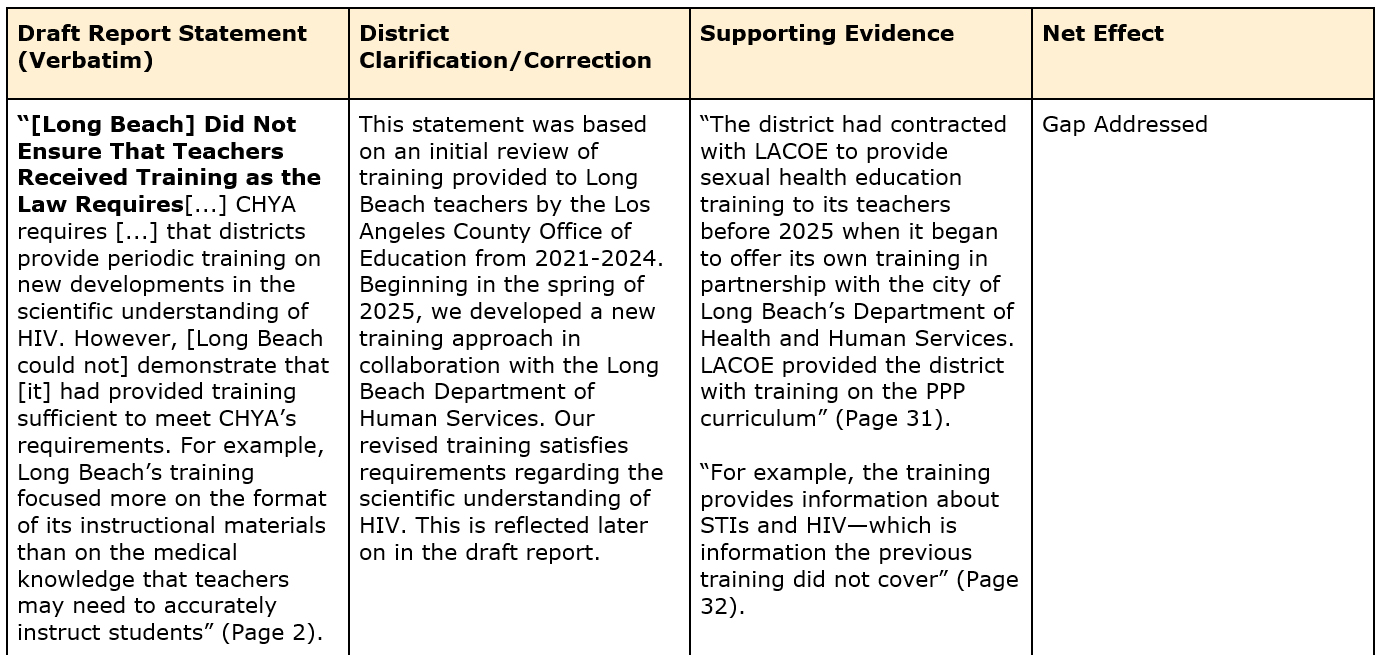

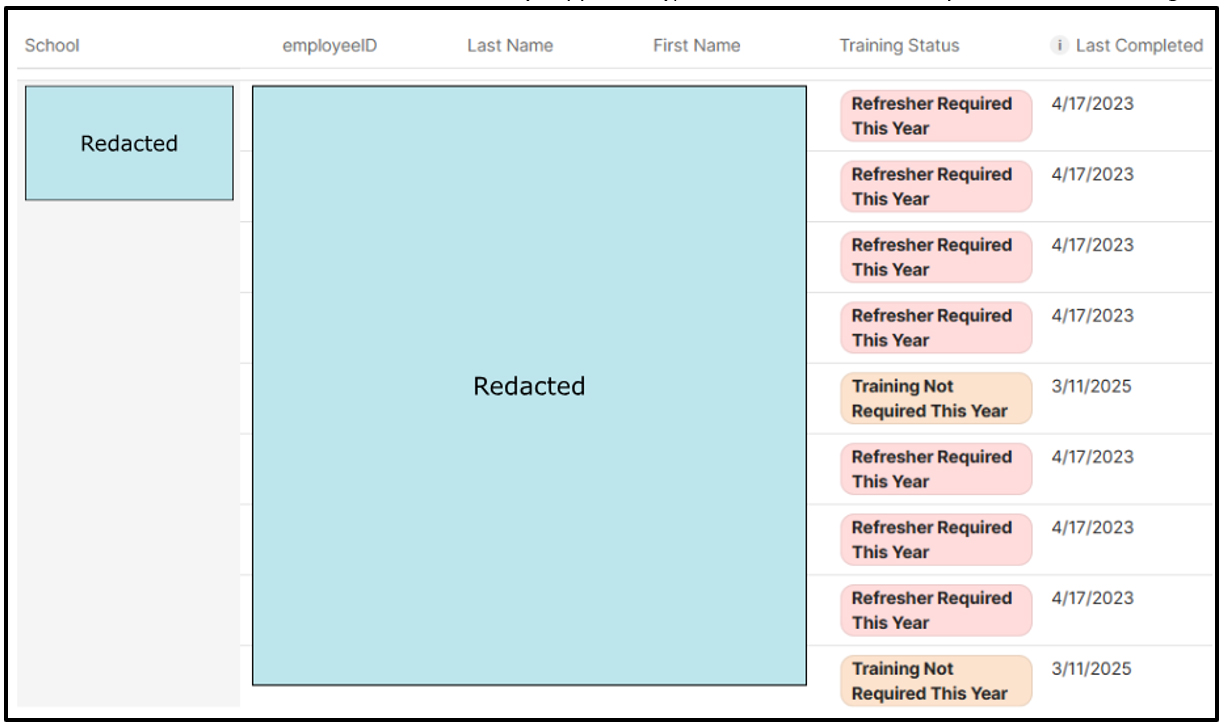

Despite these requirements, of the four districts we audited, only Long Beach has an established process to train its teachers. Long Beach determined that the requirements for regular training meant that teachers needed training every three years. The district requires its teachers to receive training in providing sexual health education instruction to students before teachers deliver that material as well as every three years thereafter, in accordance with Long Beach’s interpretation of CHYA’s requirements. The district had contracted with LACOE to provide sexual health education training to its teachers until 2025 when it began to offer its own training in partnership with the city of Long Beach’s Department of Health and Human Services. The district indicated that it formerly used paper sign‑in sheets to monitor training attendance and began tracking teachers’ compliance with its three‑year training requirement through a training dashboard in March 2024. However, because the district’s data did not have complete records about each teacher who provided CHYA instruction, we were unable to determine the extent to which Long Beach ensured that its teachers complied with its three‑year training cycle requirement.

Further, it was not apparent from the training content that Long Beach shared with us that the training the district provided to its teachers through LACOE was sufficient to meet CHYA’s requirements for regular training. LACOE provided the district with training on the PPP curriculum. Specifically, instead of addressing medical research or updates on the understanding of HIV, the training slides focused primarily on the format and content of the instructional materials, approaches for remaining neutral when teaching about potentially sensitive issues, and suggestions for dealing with difficult questions from students. According to Long Beach’s science curriculum leader, the district believes that the publisher for its instructional materials keeps those materials up to date and medically accurate and, therefore, by requiring its teachers to attend the training on the instructional materials, the district was ensuring that the teachers were trained as required. However, because the 2022 training materials we reviewed did not clearly demonstrate that the training covered updated information on required topics, we could not verify that assertion. Consequently, we could not determine whether the training Long Beach used before 2025 met the requirements in CHYA. We also reviewed the training Long Beach has provided since 2025 and found that it was improved in some respects compared to the previous training, but it still did not address the full range of training required by CHYA. For example, the training provides information about STIs and HIV—information the previous training did not cover—but does not ensure that instructors are trained in the subjects of healthy relationships or medical information about pregnancy.

The other three districts have not established processes to ensure that their teachers receive the necessary training. District administrators at Sonoma explained that they rely on school administration to inform them when new teachers may need training. Rocklin and Tulare both described how, in general, experienced teachers at each school train new teachers on sexual health education materials. However, none of these districts had established requirements for regular training or tracked the frequency of teacher training. Rocklin said that its teachers obtained training when the district adopted PPP in 2017. Sonoma said that it believed the teachers who provide instruction had been trained in previous years, and Tulare said that turnover in its administrative staff prevented it from demonstrating whether or when teacher training had occurred, although an administrator at the district believed that some teachers had been trained by a local health care provider.

The districts gave varying reasons for not establishing ongoing teacher training. Both Sonoma and Tulare indicated that they were unaware of the requirement for regular training. Rocklin indicated that it trains its teachers on new curriculum when it updates that curriculum. Its associate superintendent stated that the district follows CDE’s recommendation of updating curricula every eight to 10 years. Notwithstanding Rocklin’s understanding of the guidance it said CDE provided, we find that conducting training at that interval is not sufficiently frequent to meet the law’s training requirements. The lack of timely training for teachers in these three districts may result in teachers not being knowledgeable about the most recent medically accurate research on human sexuality, healthy relationships, pregnancy, HIV, and other STIs, which could affect the quality of the instruction they provide to students.

The districts were generally open to the idea of adopting more robust and regular training. Sonoma did not identify anything that would prevent it from defining a reasonable frequency for providing training and establishing a process to ensure that teachers receive such training on CHYA‑related topics at that frequency. Rocklin indicated that implementing more frequent periodic teacher training as CHYA requires was achievable, and Tulare similarly agreed that establishing a more robust training program was achievable and indicated that it had begun working with its county office of education to organize training.

CHYA allows districts to use contractors to provide sexual health education instruction and HIV prevention education to students, and the Legislature asked us to determine whether districts used contractors in this manner. We found that none of the districts we reviewed relied on contractors to provide instruction to students. Instead, the districts told us that their teachers provided the instruction during the period we reviewed—school years 2021–22 through 2023–24.8 Further, about 24 percent of districts that responded to our survey reported using the services of contractors, including in-person classroom instruction and video-based instruction, as the primary method for delivering CHYA instruction.

Districts Appropriately Notified Parents About Sexual Health Education, but They Did Not Track Cases in Which Parents Opted Students Out of the Instruction

CHYA contains three key requirements that enable parents and guardians (parents) to make decisions about their students’ participation in comprehensive sexual health education and HIV prevention education. First, districts must notify parents about the planned comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention instruction that will occur in the upcoming school year. We refer to this as the parental notice. CHYA requires districts to provide the parental notice at the beginning of the school year or at the time parents enroll their students in the district. Second, districts must include in the parental notice an advisory that the written and audiovisual educational materials used in this instruction are available to parents for inspection. Third, districts must notify parents of their right to excuse their students from all or part of this instruction by notifying the district in writing of their request to opt their students out of the instruction. CHYA does not require parents to justify a decision to opt their student out of instruction, and it requires that alternative educational activities be made available to students whose parents have opted them out of this instruction.

Long Beach, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare all notified parents about upcoming instruction, parents’ ability to preview instructional materials, and parents’ ability to opt their student out of instruction in academic years 2021–22 through 2023–24. For example, Long Beach posts guidance for parents and students on its district website, and it notifies parents about that website content. The guidance contains information about CHYA instruction and discusses parents’ rights for previewing the instructional materials and for opting students out of that instruction. Further, Sonoma has an online registration process through which it provides parents with an annual parent’s rights notification. This parental notice, which the district also posts on its district website, includes information about CHYA instruction and parents’ ability to preview the instructional materials and opt students out of CHYA instruction. We also found that teachers we interviewed generally described sending notifications to parents weeks in advance of beginning instruction.

The four districts also notified parents that the instructional materials were available for review. Sonoma sent paper and electronic notices to parents telling them they could examine instructional materials, and Tulare sent an electronic notice to parents before the start of instruction, specifying that instructional materials were available for review at their school’s main office. Long Beach and Rocklin provided parents with web links that allowed them to preview electronic versions of the instructional materials. However, despite the availability of material, the districts said that they had very few instances of parents requesting to preview the materials or attending open house events for that purpose. Each district indicated that it did not formally track requests to review the instructional materials or that it had not maintained records of those requests, and CHYA does not require districts to do so. Consequently, we could not determine the actual number of such parental requests or previews.

Each of the districts we audited acknowledged the parental right to opt students out of the required instruction and attested to facilitating those requests. Teachers and administrators from these districts also spoke about how rare these opt‑out requests are. For example, one 9th grade teacher from Long Beach said that only two students had been opted out of her class during the years we reviewed. A 9th grade teacher from Sonoma indicated that they had not had an opt out in the last four years. At the two Tulare schools we reviewed, teachers reported one or two opt outs per year. The districts we reviewed described opt‑out levels that aligned with the rates districts reported in our survey. Specifically, survey respondents that provided opt‑out information generally reported few to no opt‑outs each school year.

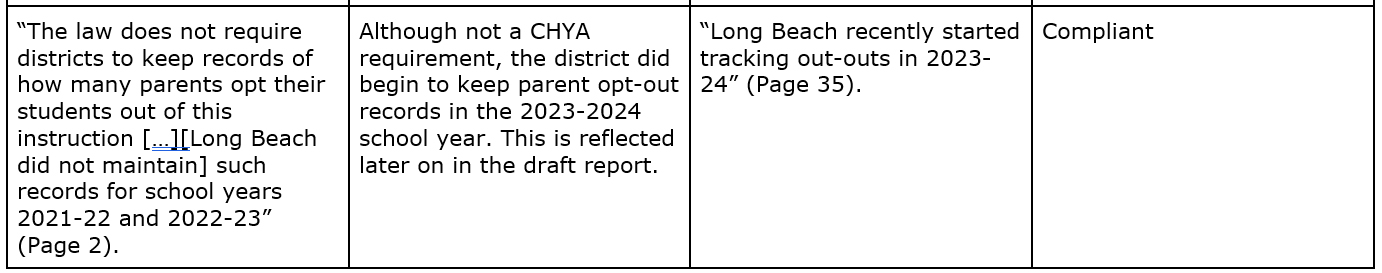

CHYA does not require districts to keep records of how many parents opt their students out of this instruction. The Legislature asked us to determine the number of students whose parents opted them out of CHYA instruction in school years 2021–22 and 2022–23 and the percentage of students who received CHYA instruction. None of the four districts we reviewed tracked opt‑outs in those years, and the absence of opt‑out records prevents us from reporting answers to these two questions. Only Long Beach recently started tracking opt‑outs in 2023–24. Long Beach’s records show that in that year, parents opted out of instruction a total of only eight middle school students and 11 high school students. The district’s course enrollment data did not provide sufficient detail for us to calculate a percentage of students who received instruction in the 2023–24 school year.

Recommendations

Long Beach

To ensure that it complies with the training requirements in CHYA, Long Beach should review its teacher training program and modify the program as necessary to align with CHYA’s requirements.

Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare

To ensure that districts periodically train all school district personnel who provide CHYA instruction, Rocklin, Sonoma, and Tulare should adopt policies and procedures that do the following:

- Define the frequency and content of training for teachers who provide CHYA instruction. The defined frequency should ensure that teachers receive timely training on the most recent, medically accurate information and that no teacher provides CHYA instruction without having first received that training.

- Track compliance with the required training.

Increased Guidance and Accountability Measures Would Better Ensure CHYA Compliance Statewide

Key Points

- Our survey suggests that many districts use instructional materials that may not comply with CHYA. The large number of districts that use materials from the same publishers as the districts we audited, as well as districts’ own reports of noncompliance, indicates an elevated risk of noncompliant instruction throughout the State.

- Because state law assigns the selection of instructional materials to local districts, CDE cannot require the use of preapproved materials. However, it could publish reviews of instructional materials to identify those that are more compliant and how to improve the compliance of published materials.

- Regular statewide monitoring of compliance would also likely help increase compliance. CDE is planning such an effort, but because it is not mandated, this monitoring could be deprioritized or discontinued.

If CHYA Required Regular Compliance Reviews and Instructional Material Reviews, District Compliance Would Likely Increase