2023-116: Local Cannabis Permitting

Cities and Counties Can Improve Their Permitting Practices to Bolster Public Confidence

Published: March 28, 2024Report Number: 2023-116

March 28, 2024

2023‑116

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the cannabis‑permitting processes at the counties of Monterey and Santa Barbara and the cities of Fresno, Sacramento, San Diego, and South Lake Tahoe. In general, we determined that cities and counties (local jurisdictions) could improve their cannabis‑permitting processes to increase public confidence and mitigate the risks of corruption.

Our review found that the local jurisdictions we reviewed did not always include several best practices in their permitting policies that help to ensure fairness and prevent conflicts of interest, abuse, and favoritism. Only two of the local jurisdictions we reviewed used blind scoring of applications, wherein the identities of the applicants are kept from those reviewing and scoring applications, and four of the local jurisdictions we reviewed did not require that all individuals involved in reviewing applications agree to impartiality statements. My office also found that all six of the local jurisdictions we reviewed were inconsistent in following key steps that their permitting policies required. For example, records at each of the six jurisdictions lacked documentation to demonstrate that all applicants had passed their required background checks.

Through Proposition 64, California’s voters legalized the nonmedical use of cannabis by adults age 21 and older. Because the resulting state law ensures that local jurisdictions retain significant control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses within their jurisdiction, we have made recommendations generally and identified best practices for all local jurisdictions that may permit cannabis businesses. Such best practices may help local jurisdictions bolster the public’s confidence in the fairness and transparency of their permitting processes.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Summary of Key Findings and Recommendations

Of the more than 240 local jurisdictions throughout the State that allowed cannabis businesses to operate as of December 2023, our audit reviewed the permitting processes of six—the cities of Fresno, Sacramento, San Diego, and South Lake Tahoe and the counties of Monterey and Santa Barbara. During our review of these six local jurisdictions, we found the following:

- As Table 1 shows, all of the local jurisdictions we reviewed did not always take reasonable steps to ensure fairness and prevent conflicts of interest, abuse, and favoritism, such as by having an administrative appeals process (appeals process) or using blind scoring. For example, Fresno lacked an appeals process for denied applications. An appeals process is critical because it helps ensure that applicants have the opportunity to contest the decision if they are denied improperly, and it can help reduce the risk of corruption.

- The local jurisdictions we reviewed inconsistently documented whether they followed their policies and procedures that require background checks for key individuals and to ensure that permit applications are complete. For example, although all local jurisdictions’ ordinances that we reviewed require applicants or certain individuals associated with an applicant to undergo a criminal background check, none of the six was able to demonstrate that it consistently reviewed or documented the results of the background checks. Inconsistently following a local jurisdiction’s policy can erode public trust in that local jurisdiction’s permitting processes.

- The local jurisdictions created policies and procedures that aligned with local ordinances, and they posted information about ordinances and permit applications to their public websites.

Proposition 64, by which California’s voters legalized under state law the nonmedical use of cannabis by adults age 21 and older, ensures that local jurisdictions retain significant control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses within their jurisdiction. Therefore, we have made recommendations generally to all local jurisdictions that may permit cannabis businesses. For example, all local jurisdictions could benefit from implementing an appeals process for denied applicants and requiring that all individuals involved in reviewing cannabis applications sign impartiality statements asserting that they do not have personal or financial interests that may affect their decisions.

Agency Comments

This audit report does not contain recommendations specific to the six local jurisdictions we reviewed, and as a result, we did not expect responses from the jurisdictions. However, three local jurisdictions—the cities of Fresno and Sacramento, and Santa Barbara County—provided responses to our audit report. Fresno disagreed with how we characterized its handling of background checks, whereas Sacramento appreciated our review and work in highlighting statewide best practices. Santa Barbara County acknowledged the value in considering some best practices as it assesses and enhances its permitting processes.

Introduction

Background

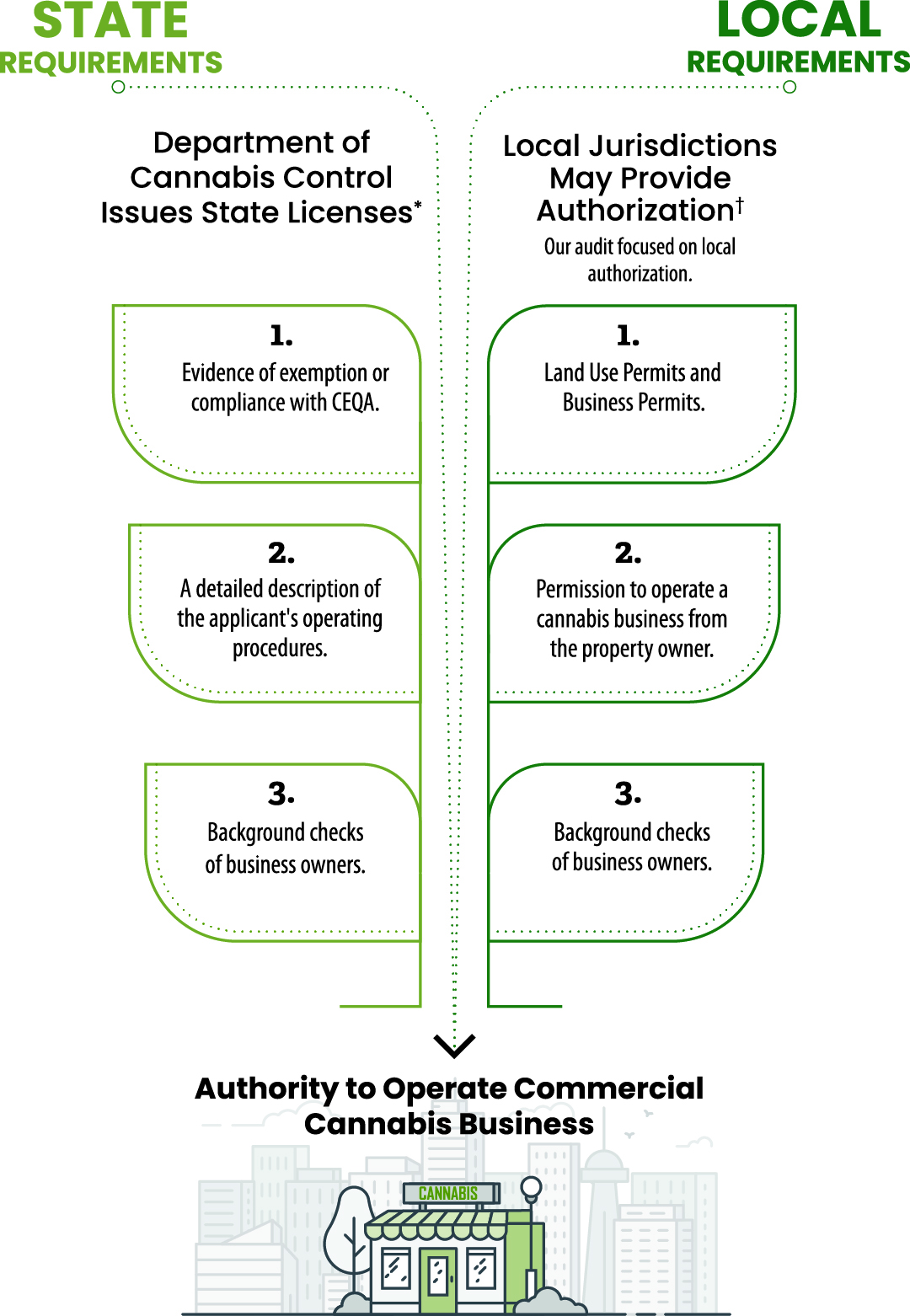

California’s voters legalized under state law the nonmedical use of cannabis by adults age 21 and older by approving Proposition 64 in 2016. State law, known as the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act, allows California cities and counties (local jurisdictions) to decide whether to allow cannabis businesses to operate within their jurisdiction and to adopt local ordinances to regulate cannabis businesses at the local level. As shown in Figure 1, for an applicant to enter the cannabis market and begin operation, that applicant must both obtain a state license and satisfy any requirements for operation imposed by the local jurisdiction in which the applicant intends to operate, such as by obtaining a permit. The State oversees the statewide licensing of cannabis businesses through a process overseen by the Department of Cannabis Control (DCC). State law requires applicants seeking a state license to provide certain information with their application, such as a list of every person with a financial interest in the applicant and a copy of the owner’s application for a background check. DCC reported in 2023 that it had issued nearly 3,800 licenses for cannabis businesses and processed more than 8,800 license renewals.1 As of December 2023, nearly 240 local jurisdictions were allowing at least one type of cannabis business to operate in their jurisdictions. Table 2 lists the key types of cannabis businesses that DCC licenses. In 2023 licensed cannabis businesses produced $5.1 billion in total cannabis sales.

In addition to needing licensure from the State, each cannabis business must comply with any requirements imposed on cannabis businesses by the local jurisdictions in which they operate. With the significant local control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses that those jurisdictions retain under state law, local jurisdictions generally may decide not to allow any types of cannabis businesses to operate, may issue permits for only certain types of cannabis businesses, or may set limits on the number of cannabis businesses that may operate in their jurisdiction. Local jurisdictions may also assess and set fees for their permitting processes, annually renew permits, and perform on-site inspections of cannabis businesses. This audit focuses on the local jurisdictions and their processes for issuing permits required to operate cannabis businesses. We refer to these permits as cannabis-related permits.

Figure 1

Cannabis Businesses Require Both State Licenses and Local Authorization Prior to Commercial Operation

Source: State law and ordinances of local jurisdictions we reviewed.

*We present a selection of requirements to obtain a state license.

† Proposition 64 safeguards local control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses. Therefore, local jurisdictions’ processes for authorizing and regulating cannabis businesses may vary. We present several examples of requirements to obtain local authorization from the jurisdictions we reviewed.

Figure 1 Description:

This figure is a flowchart with two columns that illustrate the two types of approval an applicant must obtain prior to operating a commercial cannabis business.

The left column details a selection of requirements necessary to obtain a state license from the Department of Cannabis Control. The first requirement in that column is evidence of exemption or compliance with CEQA, the second is a detailed description of the applicant’s operating procedures, and the third is background checks of owners. The right column presents examples of local jurisdictions’ requirements that may be required to obtain authorization in order to operate a commercial cannabis business. There is a footnote at the top of this column which indicates that Proposition 64 safeguards local control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses, and therefore local jurisdictions’ processes may vary. Given this, the following requirements are examples from jurisdictions that were reviewed. The first requirement shown in this column is land use and business permits, the second is permission to operate a cannabis business from the property owner, and the third is background checks of owners. This figure also reminds the reader that this audit focuses on local authorization to operate, and not state requirements.

Audit Results

Audit Objective 1:

Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives.

KEY POINT

- Under state law, local jurisdictions have the ability to decide whether to allow cannabis businesses to operate in their jurisdictions, and local jurisdictions have autonomy in creating and implementing their own policies and procedures for any permitting process they choose to adopt.

Proposition 64 safeguards local control over the regulation of cannabis businesses, allowing local jurisdictions to regulate cannabis businesses, to subject cannabis businesses to zoning and permitting requirements, and alternatively, to ban the operation of cannabis businesses altogether. In fact, as of December 2023, the Department of Cannabis Control (DCC) reported that 56 percent of the jurisdictions in the State do not allow any type of cannabis businesses to operate within their boundaries.

Although Proposition 64 allows local jurisdictions to regulate cannabis businesses at the local level, former federal guidance, which has since been rescinded, set forth the federal government’s expectations for local jurisdictions that allow cannabis-related conduct. Certain cannabis‑related activities, however, including the possession and distribution of cannabis, remain illegal under federal law and therefore can be prosecuted by federal authorities even if it those activities are legal according to a state’s laws. In August 2013, a U.S. deputy attorney general authored a memorandum for all U.S. attorneys providing guidance on when to enforce federal cannabis laws. As the text box shows, the memorandum states the expectation that states and local governments that have enacted laws authorizing cannabis‑related activity will establish strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems for cannabis‑related activity.

Former Federal Guidance on Cannabis Enforcement

… [it is the] expectation that states and local governments that have enacted laws authorizing marijuana-related conduct will implement strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems that will address the threat those state laws could pose to public safety, public health, and other law enforcement interests. A system adequate to that task must not only contain robust controls and procedures on paper; it must also be effective in practice.

Source: August 2013 Memorandum from U.S. Deputy Attorney General relating to cannabis enforcement.

Although the U.S. attorney general rescinded the 2013 federal guidance memorandum in 2018, the memorandum was in effect when California legalized the nonmedical use of cannabis by adults 21 years and older. Therefore, this guidance represents a reasonable best practice for how local jurisdictions should regulate cannabis businesses and address any threats to public safety and public health. In fact, one local jurisdiction we reviewed—Monterey County—referenced this federal guidance and used some of its language in the ordinance it adopted authorizing the operation of commercial cannabis businesses.

Each of the six local jurisdictions we reviewed adopted ordinances establishing a permitting process for cannabis businesses, but the specificity of these ordinances varied. For example, South Lake Tahoe’s ordinance and the application guidelines adopted by city council resolution specified important elements of the permitting process, such as the required application materials and other criteria for issuance of a cannabis-related permit. Conversely, Fresno’s ordinance does not specify the requirements for its cannabis permitting process. Instead, Fresno’s ordinance gives the city manager discretion to design evaluation criteria and permitting processes for issuing commercial cannabis business permits, which Fresno developed using policies and procedures.

Under the framework created by Proposition 64, local jurisdictions retain significant control to authorize and regulate cannabis businesses. Therefore, we used best practices and comparative criteria from other local jurisdictions and governments to establish the criteria we use to evaluate each local jurisdictions’ cannabis permitting processes.

Audit Objective 3c:

Determine whether local jurisdictions took reasonable steps to ensure fairness and prevent conflicts of interest, abuse, and favoritism.

KEY POINTS

- Only two of the local jurisdictions we reviewed require blind scoring of applications—a process in which the identities of the applicants are kept from the evaluators reviewing and scoring applications, which can reduce the opportunity that they will provide certain applicants with preferential treatment.

- Fresno was the only local jurisdiction we reviewed that lacked an administrative appeals process (appeals process) for applicants to contest the jurisdiction’s decision to deny their applications. An appeals process is critical because it helps ensure that applicants have the opportunity to contest the decision if they are denied improperly.

- Four of the local jurisdictions we reviewed did not require that individuals involved in reviewing applications agree to impartiality statements. Requiring such impartiality statements is a best practice to help reduce the risk of any conflicts of interest evaluators might have with the applicants.

Blind Scoring and an Appeals Process Could Help Local Jurisdictions Ensure Fairness

Local jurisdictions can use blind scoring and an appeals process to help ensure fairness and prevent favoritism. The blind scoring of permit applications reduces opportunities for those reviewing or scoring applications to improperly influence outcomes by providing preferential treatment for certain applicants. An appeals process helps ensure that applicants have an opportunity to contest the decision if they are denied improperly. Processes such as these help build public trust and are more likely to lead people to accept a decision or outcome, even when they do not agree with the decision itself. A fair process also requires an impartial decision‑maker, clearly understood rules, as well as information about any available review or appeals processes.

Of the six local jurisdictions we reviewed, four—the cities of Fresno, Sacramento, South Lake Tahoe and the county of Santa Barbara—have chosen to require a competitive process that requires scoring of permit applications for either all or some permit types. The remaining two local jurisdictions—Monterey County and the city of San Diego—have chosen not to require a competitive process that scores applications. Of the four local jurisdictions that require scoring, Table 3 shows that the city of Fresno and Santa Barbara County could benefit from implementing blind scoring of applications. In blind scoring, staff redact any identifying information about applicants, such as the business owner name, business name, or business address, from the application materials that evaluators review so the evaluators cannot identify the applicant whose materials they are scoring. Blind scoring can help prevent personal or financial affiliations between applicants and evaluators from influencing the scores. Blind scoring may also make it more difficult for elected officials to improperly influence government workers who review applications, since blind scoring would make it difficult for the evaluators to know which application the elected official wanted them to focus on. Research on fair and efficient hiring practices shows that identity-blind hiring prioritizes applicant qualifications and removes bias.2 To identify whether a local jurisdiction required blind scoring, we reviewed the local jurisdictions’ ordinances, policies and procedures, and a selection of applications and related documentation, such as application scoring records.

South Lake Tahoe’s application guidelines require it to employ blind scoring, whereby the identity of the applicant or owner will not be revealed when written proposals are scored by the reviewers. However, we found the jurisdiction did not adhere to these guidelines. Specifically, South Lake Tahoe did not fully redact the names of the business or owner on all of the applications it received before sending the applications to its evaluators. The city attorney explained that a former employee performed the redactions manually and did not involve other city staff in performing the redactions. The city attorney agreed that to avoid these same errors in the future, a better practice would be to involve the city attorney’s office in the redaction process. In fact, one applicant filed an appeal stating that the city did not follow its selection process because it did not fully redact their application, which precluded the blind scoring as required by the application guidelines. Although the hearing officer—an independent contractor who evaluated the appeal—verified that the city did not completely redact the identity of the applicant in all of the applications, he found no evidence of bias, prejudice, or favoritism by any reviewer that would have affected the results of the scoring. Nevertheless, by not following its procedures, the local jurisdiction undermined applicants’ confidence that its evaluation process was fair.

Santa Barbara County’s and the city of Fresno’s cannabis‑permitting ordinances and procedures did not require blind scoring for evaluating permit applications. Both local jurisdictions explained why they had not implemented blind scoring. Santa Barbara County explained that parts of their process could not have been scored blindly, such as those parts that relied on site visits with the applicants. However, county departments also performed portions of the initial scoring—such as evaluating premise diagrams—and blind scoring would have helped ensure impartiality in those steps. Nonetheless, in our view, nothing would have precluded performing site visits after the blind scoring of applications since the local jurisdiction has discretion in the design of the application process. Fresno’s deputy city manager indicated that incorporating blind scoring would require additional resources and would significantly delay the process. She further noted that the evaluators consisted of a panel rather than just one individual and that each evaluator was required to sign impartiality statements for each application. Having evaluators sign impartiality statements is a good practice, as we discuss later. However, we also note that although incorporating blind scoring may require additional resources, redacting applications before they are reviewed and ranked is an important additional safeguard for limiting the influence of potential biases.

Following blind scoring during the permit application stage, implementing an appeals process can also help local jurisdictions ensure fairness in the permitting process. In fact, as Table 4 shows, five of the six local jurisdictions we reviewed established a process for denied applicants to appeal the denial, and those local jurisdictions’ ordinances detailed the appeals process. At some of the local jurisdictions we reviewed, applicants have the option to appeal a denied application by submitting an appeal within a certain time frame. The person designated to hear the appeal may then receive evidence relevant to the matter and decide the appeal. The designated person may overturn a decision in certain specified circumstances. At one of these local jurisdictions, we found that this designated person is required to be an impartial decision-maker selected by a process that eliminates the risk of bias, which we believe to be a best practice. We identified evidence of appeals made during our review of a selection of applications at the local jurisdictions. An appeals process for applicants who are denied cannabis business permits is an important mechanism that allows such applicants an opportunity for a different individual to review the appeal and identify any potential errors in the original decision. Two of the local jurisdictions had appeals among the applications we reviewed and one of the five appeals we reviewed resulted in the approval of a formerly denied application. Specifically, one applicant from Santa Barbara County was denied a permit for knowingly, willfully, or negligently making a false statement of a material fact or omitting a material fact. This denial led the applicant to appeal this decision. As a result of the appeal, an administrative law judge conducted a hearing and then reversed the decision after finding that Santa Barbara County’s grounds for denial were flawed. This appeal and overturned decision shows the positive effect an appeals process has for applicants, allowing those applicants who were inappropriately denied a permit the ability to have the reason for denial reviewed.

Fresno was the only local jurisdiction that we reviewed that lacked an appeals process for denied applications. Fresno’s ordinance allows appeals only of approved permits and allows such appeals to be brought only by certain individuals, including the mayor or councilmember in whose district the cannabis business would be located. However, this process does not allow an applicant who has been denied a permit to appeal the decision. Fresno’s deputy city manager indicated that the city has followed its ordinance, which does not include an appeals process for denied applicants. She further explained that the city believes there would be a significant number of appeals that would delay the process if appealing denied applications were an option. However, the five other local jurisdictions we reviewed had appeals processes for denied applicants. Specifically, an appeal in another local jurisdiction led them to reverse the decision to deny an application because the grounds for the denial were flawed, showing the value of such an appeals process. Moreover, a lack of an appeals process can also increase the risk of unfairness in the permitting process. Appeals processes are used in different levels of government such as the federal government, including the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the state government, including the Employment Development Department, to ensure that disputes are resolved in a fair way. An appeals process is a best practice to help ensure a fair and transparent process and to reduce the risk of favoritism and abuse.

Local Jurisdictions Can Take Additional Steps to Prevent Conflicts of Interest

All six of the local jurisdictions we reviewed adopted and promulgated conflict‑of‑interest codes, as required by the State’s Political Reform Act.3 However, we found examples in each jurisdiction we reviewed in which at least one individual involved in reviewing permit applications was not required to disclose certain financial interests under the local jurisdiction’s conflict-of-interest code. To address this weakness, the local jurisdictions could implement an additional best practice whereby local jurisdictions require all individuals reviewing permit applications to sign impartiality statements, which would include whether the individual has any personal or financial interests. Disclosing non-financial conflicts of interest, such as familial or other personal relationships, goes beyond what is required under state law for financial disclosures. However, this practice would allow local jurisdictions to mitigate the risk of conflicts of interest or even the perception of such a risk in the cannabis permitting process. In particular, local jurisdictions should require all application reviewers to sign impartiality statements and, in the interest of transparency, make the signed statements or the language used for the statements available to the public, as Table 5 shows.

Each local jurisdiction we reviewed adopted and promulgated a conflict-of-interest code that requires designated positions to disclose certain financial information, such as investments, business positions, interests in real property, and sources of income, including gifts, and outstanding loans.4 Among other things, a conflict‑of‑interest code designates the positions within a local jurisdiction that are involved in making or participating in making decisions that may foreseeably have a material effect on any financial interest and requires that individuals in those designated positions make those financial disclosures. For example, someone who is a partial owner of a cannabis business, who also works as a housing and development project manager and is involved in reviewing cannabis business applications, should disclose any interest in the business if that individual’s position with the local jurisdiction is required to file financial disclosure statements. However, a weakness we found during our review of the local jurisdictions was that at least one individual involved in reviewing cannabis business applications from each jurisdiction was not employed in a designated position that required filing financial disclosure statements under the jurisdictions’ conflict-of-interest codes. Individuals involved in reviewing a permit application who are not required to complete the financial disclosures or sign impartiality statements are at a greater risk of not disclosing a conflict of interest.

All local jurisdictions should require impartiality statements from all individuals in the cannabis-permitting process to further mitigate conflicts of interest. We also believe that in the interest of transparency, it is a best practice for local jurisdictions to make these signed statements or the language used in the statements available to the public by posting them to their website. However, none of the jurisdictions we reviewed published those signed statements.

Despite not publishing such disclosures, Fresno and Sacramento have implemented the use of impartiality statements, a practice that requires staff responsible for evaluating cannabis business applications to sign a statement attesting to their not having personal relationships, affiliations, biases, or financial interests related to individuals participating in the application process. This practice goes beyond what a designated person is required to include in their financial disclosures under state law. Fresno’s deputy city manager said that the city asks all individuals who are responsible for reviewing cannabis business applications to sign impartiality statements related to each applicant. The text box shows the language Fresno uses in its impartiality statements. In Sacramento, only reviewers of equity program applications for retail business permits, which included one of the 20 cannabis business applications we reviewed, must agree to impartiality agreements.5

Both Fresno and Sacramento explained that their conflict‑of-interest policies, including the use of impartiality statements, are crucial checks to ensure a fair process and instill public confidence. Additionally, both jurisdictions explained that they reviewed these signed impartiality statements to ensure that there were no conflicts of interest, which is an important step to ensure that a designated person is verifying that the reviewers do not have conflicts of interest. In other jurisdictions, implementing a similar process in which the individuals responsible for reviewing applications sign an impartiality statement could help prevent those individuals from not disclosing conflicts of interest.

Excerpt From Fresno’s Impartiality Statement

I, _______________, a City of Fresno employee and commercial cannabis business permit application reviewer, certify that I have no personal relationship or affiliation with this applicant and have no bias based on a favorable or unfavorable relationship with this applicant. Further, I have no financial interest of any sort with this applicant.

Source: Fresno application files.

The other four local jurisdictions did not require individuals involved in reviewing cannabis business applications to sign impartiality statements. Monterey County explained that it had not considered implementing a specific policy related to individuals reviewing cannabis business applications. Santa Barbara County contracted with a third party for the initial review of applications. It included in its contract a conflict-of-interest clause that states that the contractor agrees that it presently has no employment or interest and shall not acquire any employment or interest, direct or indirect, including any interest in business, property, or sources of income that would conflict with the performance of services. In addition, Santa Barbara County indicated that local jurisdiction staff who were responsible for ranking the final application and performing site inspections had discussed the importance of impartiality with the county’s legal counsel, after which the staff verbally affirmed their impartiality. Therefore, the local jurisdiction had not considered further requiring the staff to sign an impartiality statement. Nevertheless, in any process that requires impartiality or that may be susceptible to bias, it is important to consider and implement safeguards, such as using impartiality statements, to prevent undue influence and strengthen confidence in the integrity of the process.

Audit Objective 5:

Assess the benefits and challenges of different processes for awarding local licenses, and evaluate whether some selection processes are structurally more susceptible to corruption.

KEY POINTS

- Local jurisdictions that limit or cap the number of cannabis-related permits they will issue potentially increase the value of those permits because of scarcity, leading to greater incentives for corruption committed by government officials.

- Local jurisdictions that place decision-making authority with one person so that the decisions can be based on one person’s judgment instead of clearly understood criteria increase the risk of corruption.

- Local jurisdictions would benefit from implementing best practices, such as blind scoring and an appeals process, to reduce the risk of corruption.

Proposition 64 gives local jurisdictions significant control over any cannabis permitting process they choose to implement, and the six local jurisdictions we reviewed created different ways to permit cannabis businesses. Some local jurisdictions adopted permitting processes that competitively score applications and issue a limited number of permits based on applicants’ scores. For example, South Lake Tahoe determined that it would issue cannabis-related permits to no more than four retail businesses and awarded permits to only those applicants whose applications received the highest scores. Other jurisdictions, such as Monterey County, adopted permitting processes that do not set such strict limits on the number of retail permits and instead issue retail permits to applicants whose applications comply with all the requirements in ordinance. Because this audit objective directed us to identify whether different processes are structurally more susceptible to corruption, we focused on those processes and the risks that they could be susceptible to corruption.

Corruption is dishonest or illegal behavior involving a person in a position of power, such as an elected official accepting money for doing something illegal. The U.S. Attorney’s Office recently detailed three different bribery schemes involving government officials helping to pass laws allowing commercial cannabis activity or issuing permits to certain cannabis businesses in exchange for money in California. For example, two individuals were involved in bribery and funneling bribes in exchange for influence over Baldwin Park, California’s cannabis permitting process, such as helping certain businesses obtain cannabis permits.6 Specifically, a city councilmember solicited bribe payments from businesses seeking cannabis-related permits in the city, which it had set to a limit of 25 permits. In exchange for the illicit payments, the councilmember agreed to use his position in city government to assist the companies with obtaining those permits by voting to approve the applications for those business and securing votes from other councilmembers. A former county planning commissioner agreed to act as an intermediary to funnel those bribes to the councilmember by using his internet marketing company and keeping a portion of those bribes for himself. Nevertheless, the Institute for Local Government’s publication about protecting a community against corruption indicates the importance of a robust culture of ethics and that decision-making criteria include values such as fairness. It further indicates that processes promoting transparency and limiting the risk of corruption serve to increase public confidence.

Local jurisdictions increase their susceptibility to corruption when they create scarcity by limiting the number of permits issued—thus increasing their value—without implementing additional safeguards. Capping the number of permits also increases the risk that someone would use their influence to preferentially select the applicants who will receive permits. Although South Lake Tahoe’s ordinance limited the number of retail cannabis businesses permitted in the city, it took steps that help mitigate the risk of corruption and increased its transparency and fair decision-making criteria by requiring blind scoring and providing an appeals process that allowed applicants to challenge their denied applications. This limitation on retail permits required South Lake Tahoe to approve no more than four retailers of all 21 applications it received. We identified two key best practices, such as those at South Lake Tahoe, in the text box.

Best Practices to Reduce the Risk of Corruption in Cannabis Permitting

- Blind scoring of applications to ensure that the identity of the applicants does not bias the reviewer’s/decision-makers’ score.

- Appeals processes that include a review of denied applications by an impartial decision-maker to increase transparency and public confidence in the outcomes of the permitting process.

Source: Local jurisdictions’ permitting ordinances and polices.

One appeal that we reviewed alleged that two of the individuals who were owners of two cannabis businesses, which were ultimately awarded permits, were part of a subcommittee that wrote South Lake Tahoe’s ordinances and scoring criteria for the local jurisdiction’s cannabis-permitting process. The appeal further alleged that the subcommittee possessed decision-making authority and established the cannabis program, thereby providing those two owners with an unfair advantage in completing their applications. However, after reviewing the cannabis business application guidelines, written appeal, and responses by and information from the local jurisdiction and from the businesses involved in the appeal, the hearing officer—an independent contractor—denied the appeal. The hearing officer, appointed to review, investigate, and decide South Lake Tahoe’s cannabis appeals, found that there was no evidence that the subcommittee developed the scoring criteria for the applications and no facts to suggest that the subcommittee had any influence over the content of the ordinances. Further, the hearing officer stated that the subcommittee was a citizen’s advisory committee that only provided background information to the city council. Nevertheless, having an independent appeals process to promote transparency and resolve disputes is important to better ensure that applicants have recourse if they are evaluated unfairly by the local jurisdiction.

Our review of applications at Fresno identified policies that may make its cannabis-permitting process more susceptible to corruption. Specifically, the city manager is responsible for making the decision to award or deny a permit, and the city limits the number of cannabis‑related permits it can approve—such as limiting permits to no more than 14 cannabis retail businesses. The text box includes an excerpt from Fresno’s application procedures and guidelines, which discusses the city manager’s authority to make a final determination on which applicants to award a permit. In our view, such a process lacks transparency for how potentially lucrative cannabis-related permits are being issued by the city manager, possibly eroding public trust in the process. In an environment where a city sets a cap on cannabis-related permits, it is even more important that the public fully understand the permitting process and decision-making criteria.

Excerpt From Fresno’s Application Procedures and Guidelines

“The city manager will make a final determination regarding the applicants to be awarded a permit and the decision is not necessarily determined by the application score alone. If requested by the city manager, the applicants may be requested to provide additional information or respond to further questions before the city manager makes the final decision on the awarding of a permit(s). The city manager may also take into consideration the quantities of applications for different permit types.”

Source: Fresno’s 2021 Commercial Cannabis Business Application Permit Procedures and Guidelines. Emphasis added.

Even though such authority can be used for laudable purposes—as in Fresno’s case with equity applicants—the integrity of the city’s process significantly relies on one person who can effectively ignore an application’s score under the current permit procedures and guidelines. In the case of using this authority in a positive manner, the deputy city manager indicated that the city manager gave preference to the highest ranked equity applicants over non-equity applicants by approving the top three ranking equity applicants before approving any non-equity applicants. Specifically, the city manager selected an equity applicant to obtain cannabis-related permits in place of a non-equity applicant. The non‑equity applicant scored high enough to obtain the cannabis-related permit, but after the city manager selected the equity applicant, the non-equity applicant was no longer eligible for a cannabis permit due to proximity location requirements in city ordinance. Because equity applicants were not scored using the same metric that applied to non-equity applicants, we could not compare the two to see whether an equity applicant scored higher than a non-equity applicant. Nevertheless, this shows that the city manager used his authority by prioritizing equity, which is a priority of the State.

Although the city manager deserves credit for prioritizing equity and awarding the established minimum number of equity permits, there are no limitations in ordinance or in the policy restricting the city manager’s discretion and decision‑making authority. This type of permitting structure can increase the risk of corruption since only one individual decides who should get a permit, and that individual can deviate from the scoring even though that scoring is ostensibly the basis for awarding a permit.

Fresno also had a control that may reduce the risk of corruption—a process to appeal the city manager’s decision—but we identified two concerns with the process. Our first concern is that the process does not allow applicants to appeal denied applications. Fresno’s appeals process allows certain individuals, including the mayor, or the councilmember in whose district the cannabis business would be located to appeal the decision of an approved permit, but it does not allow applicants who are denied a permit to appeal the decision. In fact, we saw several cases in which a councilmember appealed the city manager’s decision to approve a cannabis business permit, leading to one applicant being denied, and another applicant who scored lower to be approved. The applicant whose application was originally approved would not have any opportunity to appeal this denial since the application was now denied, which threatens fairness of the process. Our second concern is that the appeals process allows councilmembers who file an appeal to also vote on the appeal decision. For example, a councilmember from one district appealed one application that the city manager had approved. During a city council meeting, the councilmember voted for the denial of that application after the discussion in the meeting. By allowing councilmembers to appeal the decision to award a permit and also vote on the appeal, the process provides an opportunity for a single councilmember to exercise significant influence over which applicants ultimately obtain cannabis-related permits. Having separation of duties or an impartial decision-maker to decide the appeal could help reduce the risk of corruption in the cannabis-permitting process.

Fresno’s deputy city manager stated that the city followed its ordinance, which does not include an appeals process for denied applicants. Further, she indicated that if Fresno were to create an appeals process for denied applicants there would be a significant number of appeals, thereby delaying the permitting process. Regardless, because Fresno does not have a process for applicants to appeal denied applications, it denies those applicants an opportunity to have their concerns heard. Further, Fresno’s existing process that allows a council member who raised an appeal of an approved application to vote on the outcome of that appeal could raise questions about integrity of the process and undermine the public’s trust in the process.

To mitigate corruption in the permitting process, local jurisdictions can implement certain best practices. In particular, implementing blind scoring of applications so that the identity of the applicants is not shared with the reviewers can help ensure that an evaluator does not give preferential treatment to certain applicants. Further, ensuring that there is more than one person responsible for approving or denying permits increases public confidence in the fairness of the permitting process. Finally, instituting an appeals process for denied applications, in which an impartial decision-maker reviews the appeal, increases transparency by providing applicants with an opportunity to contest the decision to deny their application if it was not made in accordance with the local jurisdiction’s established permitting process.

Audit Objective 4:

For a selection of permits at each of the six local jurisdictions, determine whether the local jurisdiction followed its policies and procedures when issuing the local licenses.

KEY POINT

- Local jurisdictions have inconsistently documented whether they followed their policies and procedures when ensuring that background checks occurred and that permit applications were complete.

We Selected Applications From Each Local Jurisdiction to Determine Whether the Jurisdictions Followed Their Policies and Procedures

As Table 6 demonstrates, we judgmentally selected 20 applications for review from five of the six local jurisdictions, and we reviewed 21 applications from South Lake Tahoe because it had received only a total of 21 applications. Some of our six local jurisdictions had additional information available that assisted us in making our selection. For example, Fresno’s list of applications documented the reason an application was denied, allowing us to select applications that had different reasons for denial. Where possible, we selected some applications that a jurisdiction had denied and the applicant had subsequently appealed. We also considered, where possible, the cannabis business category, such as retail, cultivation, or microbusiness, to ensure that we included a variety of business types in our selection.

To determine which processes to test, we reviewed each local jurisdictions’ ordinances, policies, and procedures and identified key controls that would help ensure public health and safety and fairness in the process. Two of the key controls we identified were performing background checks and ensuring that applications were complete. To test the applications at each local jurisdiction, we reviewed applications, including business plans, site diagrams, and land ownership information; we also reviewed the local jurisdictions’ evidence of reviewing the applications; and we interviewed local jurisdiction staff knowledgeable about the applications.

The Six Local Jurisdictions We Reviewed Were Inconsistent in Documenting Required Criminal Background Checks

Although the ordinances of all six local jurisdictions’ we reviewed require that applicants, or certain individuals associated with an applicant, undergo a criminal background check, we found that none of the six was able to demonstrate that they consistently reviewed or documented the results. A criminal background check is the process of screening a person’s criminal history to determine whether that individual has been convicted of any disqualifying misdemeanors or felonies. The Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act does not mandate that local jurisdictions require applicants of cannabis-related permits to undergo background checks. However, each of the local jurisdictions have recognized the importance of requiring background checks and have reflected this in their ordinances. For example, Sacramento’s ordinance generally prohibits involvement with a cannabis business of any individuals who have been convicted of an offense that is substantially related to the qualifications, functions, and duties of a cannabis business; such offenses include a violent felony, a serious felony, or a felony involving fraud, deceit, or embezzlement. The text box provides further examples of disqualifying convictions from several of the local jurisdictions we reviewed. As Table 7 shows, all local jurisdictions we reviewed inconsistently documented whether they followed their policies requiring background checks. When a local jurisdiction does not document the results of all background checks during the permitting process, it calls into question whether that local jurisdiction adequately addressed public safety concerns. Further, inconsistently following a local jurisdiction’s policy can erode public trust in that local jurisdiction’s permitting processes.

Examples of Disqualifying Convictions

- Felonies involving fraud, deceit, or embezzlement.

- Felonies for using a minor in activities involving controlled substances, such as transporting or selling.

- Crimes of moral turpitude.

- Felonies for certain drug trafficking offenses.

- Extortion.

Source: Ordinances of local jurisdictions we reviewed.

Of the 16 applications requiring background checks in Sacramento that we reviewed, we found shortcomings for 10 applications.7 Specifically, we found that Sacramento lacked clear documentation demonstrating that eight applicants had passed background checks. Sacramento cannabis program staff explained that before 2020, another department provided the cannabis department with a listing of individuals who had passed the background check, which the program staff would input into a spreadsheet. When we reviewed the spreadsheet, we found that it only contained the names of individuals and, generally, their birthdates, but lacked any other information, including the dates of the results or whether the individuals had passed the background checks. Beginning in mid-to-late 2020, Sacramento updated its process by having the cannabis program staff check the spreadsheet maintained by the other department performing the background check, which indicates the applicant’s or owner’s name, the results of the background check, and the date of the results.

In the remaining two applications in which we identified problems and for which the applicants ultimately received their cannabis-related permits, Sacramento had not ensured that background checks had been completed. The cannabis program manager informed us that neither applicant had submitted all of the documents necessary to complete the background checks. She explained that it had issued the permits on the condition that the applicants successfully pass their criminal background checks. However, the applicants had submitted their documentation to the wrong city department, and the cannabis program did not follow up. After we brought this concern to Sacramento’s attention, staff contacted the individuals and have since received verification that they passed the background checks. Nevertheless, the cannabis program manager explained that Sacramento recently amended its permitting process so that it no longer issues any permits until it has received the results of required background checks.

Santa Barbara County’s executive office, which oversees cannabis permitting, issued permits to 11 of the 13 applicants we reviewed without receiving documentation from the sheriff’s office that each owner had passed a background check. According to Santa Barbara County’s deputy county executive officer, permitting staff receive notification from the sheriff’s office only when individuals have a potentially disqualifying conviction, but permitting staff do not receive any other information pertaining to the background check, including information confirming that an applicant has passed. Although the deputy county executive officer indicated that all of the individuals required to undergo background checks passed their background checks, she agreed that the county executive office should document for all required individuals whether they had passed criminal background checks.

An example from Monterey County shows a best practice that other local jurisdictions should implement. Information from background checks is confidential and includes personal information, such as names and dates of birth. State law makes it a crime to improperly access or disseminate this confidential information. Monterey County’s process is to document the results of its background checks in a way that maintains the confidentiality of the information and provides the results necessary to document whether an individual passed or failed. Monterey County Sheriff’s Office provides notifications to the cannabis program reporting the results of background checks. On these notifications, the sheriff’s office only indicates the name of the individual whose criminal record was reviewed, and the results of that review; this reporting is a best practice. We did not see these types of notifications at Santa Barbara County, for example, which instead received no notification unless someone did not pass the background check.

One Local Jurisdiction Did Not Demonstrate That It Followed Its Process for Verifying Completeness

Although the six local jurisdictions we reviewed required applicants to submit complete applications, one local jurisdiction did not consistently determine whether applications were complete. Verifying that an application is complete ensures that applicants have demonstrated that they meet the qualifications necessary for operating as a cannabis business. Similarly, accurately tracking the completeness of applications helps jurisdictions combat inconsistencies that may decrease public confidence in the cannabis-permitting process. As Table 8 shows, before December 2021 San Diego could not demonstrate that it followed its documented process for ensuring that applications were complete.

To ensure that all applicants meet the requirements to operate a cannabis business, the local jurisdictions must verify that all required elements of an application are complete. For example, a South Lake Tahoe ordinance requires that certain city staff review all applications for completeness, and the jurisdiction’s application guidelines require that it notify applicants of missing items or that the applications are complete. To notify applicants, South Lake Tahoe sends a letter to the applicant with a checklist of outstanding items that the local jurisdiction needs to consider an application complete. South Lake Tahoe followed its process by sending letters to all 21 applicants, informing them that the applications were complete.

In contrast, San Diego could not demonstrate before December 2021 that it followed its documented process for ensuring that applications were complete. San Diego’s policy states that its minimum submittal requirements checklist establishes the minimum details that must be included in all plans and documents required to be included in the application and that staff will review applicants’ documents against this checklist. For applications submitted before December 2021, San Diego simply entered into its tracking database the date the application was deemed complete. However, for 13 of the applications we reviewed, San Diego could not provide evidence that it followed its policy to compare the applications to the checklist, all of which were submitted before December 2021. San Diego’s project manager stated that the local jurisdiction’s adoption of an online permitting process in December 2021 has improved its documentation and record retention. In fact, we reviewed seven applications that San Diego received after December 2021 and verified that city staff had performed appropriate checks for completeness using the online system.

Audit Objective 3b:

Determine whether local jurisdictions’ policies and procedures comply with relevant state and local laws and regulations.

KEY POINT

- Proposition 64 does not set specific conditions with which local jurisdictions must comply when creating any permitting processes they choose to implement. The local jurisdictions we reviewed aligned their policies and procedures, as applicable, with their local ordinances for cannabis‑permitting processes.

When approving Proposition 64, the voters found and declared that Proposition 64 safeguards local control over adult-use cannabis businesses. The California Constitution gives local jurisdictions the power to make and enforce certain ordinances within their limits. Under the framework for legalizing nonmedical adult‑use cannabis created by Proposition 64, local jurisdictions may establish their own permitting processes to regulate cannabis businesses. Further, the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act does not set specific requirements for, or establish oversight of, local cannabis-permitting processes, and local jurisdictions may include the details of any permitting process they choose to adopt in ordinance, policies and procedures, or both. Because of this significant local control, we make our recommendations generally to all local jurisdictions that permit cannabis businesses rather than make recommendations directly to the Legislature.

We reviewed the six local jurisdictions’ laws and found that all six adopted ordinances that either established or authorized the establishment of a permitting process. These ordinances varied in specificity: some local jurisdictions specified the permitting process in the ordinances while others adopted ordinances directing staff in the jurisdiction to develop more detailed or specific permitting policies outside of the ordinances. Whether prescribed in ordinance or detailed in separate policies and procedures, all six local jurisdictions created and documented the details of their cannabis-permitting process. We also reviewed the cannabis-permitting policies and procedures at each of the six selected local jurisdictions, as applicable, and verified that they complied with key requirements in applicable local ordinance. We did not identify any problems in this area.

Audit Objective 3a:

Determine whether cannabis business licensing and permitting policies and procedures are in place and clearly communicated to the public and potential licensees.

KEY POINTS

- All local jurisdictions we reviewed made their ordinances and permit application forms available on their websites for access by the public, including potential permittees.

- Several local jurisdictions provided additional information on their websites, such as frequently asked questions, application instructions, and fee information.

Publicly available information is critical for ensuring the transparency of local jurisdictions’ operations and decisions. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, transparency promotes accountability by providing the public with information about what their government is doing. The Institute for Local Government recommends that local agencies post regulations, permit information, and permit application forms on their websites to potentially enhance public trust and confidence. To evaluate the transparency of the local jurisdictions’ permitting processes, we reviewed the local jurisdictions’ public-facing websites for information on the permitting process. In doing so, we verified whether the cannabis-related ordinances, policies and procedures, and application forms were clearly posted to the jurisdictions’ websites for access by the public. Each jurisdiction we reviewed made the information recommended by the Institute for Local Government available to the public through their websites, as Table 9 shows. For example, Sacramento has a webpage for the Office of Cannabis Management, with links to information on the equity program, cannabis business operating permits, and cannabis-related regulations. The webpage for the cannabis business operating permits also links to the application form, which the applicant can complete and submit online.

In our review of the local jurisdictions’ public websites, we also found that some local jurisdictions provided additional information on the permitting process, including step-by-step guidelines on navigating the permitting process, which we considered a best practice. Providing this additional information increases the transparency of the permitting process for potential applicants and the public. Four of the six local jurisdictions followed all of the best practices outlined in Table 9. For example, Santa Barbara County created supplemental information for the public that includes a flow chart that illustrates the online application process and the steps taken by county staff to review applications.

All of the local jurisdictions included cannabis-related permit fees on their public websites, including South Lake Tahoe, which included amounts for permit and license fees, annual inspection fees, and renewal fees, among other fees. By clearly communicating information about fees, local jurisdictions increase their transparency and accountability to the public and to potential applicants.

Audit Objective 6:

Review and assess any other issues not covered in the audit objectives that are significant to the audit.

KEY POINTS

- It took local jurisdictions, on average, more than 2.5 years to approve the applications reviewed in this audit.

- Some local jurisdictions have created programs to assist applicants from populations negatively impacted by cannabis criminalization (equity programs), but most of these programs that we reviewed were still relatively new, with few equity applicants having received cannabis-related permits.

- Local jurisdictions charge applicants fees—that varied widely in amount for the six jurisdictions we reviewed—to apply for and complete the cannabis‑permitting process.

In conducting our audit, we identified certain other issue areas not covered in the audit objectives and on which we present information in the following sections. These areas include the length of time it took the six local jurisdictions to process permit applications, the local jurisdictions’ equity programs, and the fee amounts the local jurisdictions charge applicants to complete the cannabis-permitting process. We present these issue areas in the audit for the sole purpose of increasing awareness about them, including awareness of the potential barriers to entry some of these issue areas may cause for applicants. However, the scope of the audit request did not ask us to evaluate the length of time it took jurisdictions to process applications, to assess their equity programs, or to review each local jurisdiction’s fees relative to the actual costs of administering cannabis-permitting programs.

Local Jurisdictions Took an Average of Two and a Half Years to Process the Applications We Reviewed

The local jurisdictions we reviewed took more than two and a half years, on average, to process and approve the applications that we selected for review.8 Generally, the local jurisdictions we reviewed required each applicant to obtain one or more permits in order to begin operation. For the applications we reviewed at each local jurisdiction that were approved or still in progress, we identified the date the applicant submitted the application to the jurisdiction and the date the jurisdiction approved the final cannabis-related permit or the date we obtained the data from the jurisdiction, respectively. Table 10 shows the average length of time each local jurisdiction took to process the applications and approve the required permits. Of the applications we reviewed, the local jurisdictions took an average of 1.6 years in Fresno to 3.9 years in San Diego, to approve cannabis-related permits after an applicant submitted the initial application. Overall, the applications still in progress as of the date of our review had been pending for three years on average.

Some local jurisdictions cited several reasons for the lengthy process, such as the time it takes applicants to submit all of the required application information. Monterey County and Santa Barbara County noted that it takes a long time for applicants to satisfy all requirements for environmental reviews. Monterey County also said that contributing factors include, for example, the time it takes for applicants to submit the information needed to perform background checks. Sacramento and San Diego similarly indicated that it can take additional time for applicants to submit all required documents. Required documents can include, for example, verification that property owners have consented to the use of the proposed business property to operate a cannabis business and proposed business plans. Moreover, Monterey County’s equity assessment indicated that lengthy processing times may result in unintended barriers to obtaining permits. Because applicants may incur some operating expenses, such as rent, during the time they are waiting for permit approval and before they can begin to generate revenue, such expenses over months or years could represent a hardship to some applicants.

Although Santa Barbara County included in its ordinance a required time frame for processing applications, that jurisdiction had some of the longest application‑processing times among the applications we reviewed. Santa Barbara County amended its ordinance in November 2021 to require applicants to submit a business permit application within 30 days of receiving approval of their land‑use permit. Of the seven applications we evaluated that received land-use approval after November 2021, the local jurisdiction allowed four applicants to apply for their business licenses after the 30-day window had closed, and it allowed one applicant to submit a business license application after 183 days. As Table 10 shows, Santa Barbara County issued 10 permits that we reviewed, the processing time of which averaged 3.4 years, the second longest of the six local jurisdictions we reviewed. Santa Barbara County’s deputy executive officer explained that the jurisdiction does not enforce this processing-time requirement because it is primarily concerned with the applicants beginning to prepare the necessary documents for the next step of the application process. Nevertheless, required time frames in local ordinances may not shorten the amount of time taken to process applications if local jurisdictions do not consistently enforce these requirements.

Although Not Required to Do So, Some Local Jurisdictions Have Created Equity Programs to Assist Applicants From Populations Negatively Impacted by Cannabis Criminalization

Under the California Cannabis Equity Act, local equity programs adopted or operated by a local jurisdiction focus on the inclusion and support of individuals and communities in the cannabis industry who are linked to populations or neighborhoods that were negatively or disproportionately impacted by cannabis criminalization (populations negatively impacted by cannabis criminalization). Although the California Cannabis Equity Act defines what constitutes a local equity program for its purposes, it does not require that local jurisdictions conduct an equity assessment or develop an equity program. Multiple equity assessments, including those from Sacramento and the county of Monterey, have found that historical cannabis criminalization has disproportionally affected some demographics in local jurisdictions’ areas within California, including African American and Hispanic populations. Furthermore, according to the DCC’s website, the long-term consequences of cannabis criminalization continue to affect people convicted of cannabis offenses, their families, and the communities in which they live. To counter these consequences, the State provides state license fee waivers and technical support to equity business owners, and some local jurisdictions have developed equity programs, though the California Cannabis Equity Act does not require local jurisdictions to do so.9 DCC has identified several challenges for people seeking to enter the cannabis industry, as the text box shows. DCC provides support to equity business owners in various ways, such as waiving or deferring state licensing fees and providing technical support to navigate the state licensing process. Further, the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development administers the Cannabis Equity Grants Program to provide grant funding to assist local jurisdictions with their equity programs. Specifically, the program is intended to advance economic justice for individuals most harmed by cannabis criminalization and poverty by providing support to local jurisdictions as they promote equity and eliminate barriers to entering the newly regulated cannabis industry for equity program applicants and licensees. In fiscal year 2023–24, $15 million was available to be awarded. Local jurisdictions’ equity programs may provide support such as priority application processing, assistance securing capital and business locations, reduced or waived local permit fees, assistance in paying state licensing fees, and technical training and support. By providing equity assistance to those from populations negatively impacted by cannabis criminalization, both the State and local jurisdictions can help lower some of the barriers to entry into the cannabis industry.

DCC Has Identified Many Challenges for Potential Cannabis Business Owners

- Getting access to capital.

- Understanding complex regulatory requirements.

- Finding locations where cannabis businesses can operate.

- Developing business relationships.

- Getting technical support.

Source: DCC’s website.

Of the six local jurisdictions we reviewed, only Sacramento had an operational program that issued permits to equity applicants. In May 2018, Sacramento completed a cannabis equity study, which found that certain demographics and certain areas of the city were disproportionately affected by past enforcement of cannabis laws.10 The study recommended two general categories of equity participants: those who live in low-income households and have lived in one of the identified areas for five or more consecutive years from 1990 through 2011, or those who live in low‑income households and were, or are an immediate family member of someone who was, convicted of a cannabis-related crime from 1990 through 2011. In response to the study’s findings, the city council adopted a resolution in August 2018 establishing the Cannabis Opportunity Reinvestment and Equity (CORE) program. The CORE program seeks to reduce the barriers of entry and participation for communities that have been negatively affected by the disproportionate enforcement of cannabis‑related crimes by providing program participants with benefits such as business management training, priority processing of cannabis-related permits, and waived city fees—$23,610 for retail applicants. Since the city council approved the CORE program in 2018, Sacramento has issued permits to 34 CORE applicants, and the city expanded its limit on the number of cannabis-related retail storefront permits, adding the possibility for 10 additional permits that are available only to CORE participants.

As for the remaining five local jurisdictions, Santa Barbara County and the city of South Lake Tahoe do not have equity programs, and the county of Monterey and the cities of San Diego and Fresno have nascent or early-stage equity programs. Santa Barbara County’s deputy county executive officer told us that the county does not currently plan to develop an equity program and the public has not voiced a specific concern about it. South Lake Tahoe’s city attorney explained that the jurisdiction’s process did not have considerations for equity applicants and it does not currently plan to issue any more cannabis-related permits to new businesses. San Diego adopted its equity assessment report in October 2022; the jurisdiction conducted the assessment to create the foundation for a cannabis equity program. San Diego’s development project manager indicated that the city is in the process of developing an equity program. The city of Fresno and the county of Monterey have both implemented equity programs, but neither jurisdiction has yet issued permits to equity applicants to allow them to start operating. Fresno’s equity program serves to address the historical impact of federal and state drug enforcement policies on low‑income communities, and the jurisdiction set aside a minimum of one out of every seven commercial cannabis retail permits for equity applicants, among other things. Monterey County’s equity program includes benefits such as technical and legal assistance, access to low or no interest loans, and application and permit fee waivers.

Fees Related to Cannabis Permitting Varied

State law allows local jurisdictions to impose fees to cover the reasonable cost of any permitting process. Each jurisdiction we reviewed provided us with documentation of its calculated costs used to support setting its fees—which can vary for several reasons, including the type of cannabis business and business location—related to administering the local jurisdiction’s cannabis-permitting program. The fees that applicants must pay typically include those for land-use permits and local business permits. Table 11 shows the fees for the local jurisdictions we reviewed for cannabis‑related permits. For example, the land-use permit fees we reviewed varied from $4,330 in Sacramento to $13,390 in Fresno. Local jurisdictions charge fees to recoup the costs of administering a permitting process, though such fees can present a barrier to entry if costs are high. The fees for cannabis-related business applicants to obtain land-use permits were generally similar to the fees for obtaining land-use permits for other types of businesses. However, there are few types of processes or fees available against which we can compare the cannabis-related business permit fees.

Because these permitting fees can present a barrier to entry into the cannabis market for some applicants, particularly those from populations negatively impacted by cannabis criminalization, some jurisdictions have sought to address high fees through their equity programs. The cities of Fresno and Sacramento, and the county of Monterey have all determined that high costs are a significant barrier to entry, and their equity programs waive some costs, such as permit fees, for approved applicants. For example, Monterey County’s equity program offers waivers for various fees, including the business permit and land-use permit.

Audit Objective 2:

Using available information regarding permitted commercial cannabis activity in cities and counties throughout the State, as well as other relevant criteria, select six local governments for review.

KEY POINT

- Using information about size, geography, permitting process, and number of permits, we selected the counties of Monterey and Santa Barbara and the cities of Fresno, Sacramento, San Diego, and South Lake Tahoe.

We selected six local jurisdictions for this audit: the cities of Fresno, Sacramento, San Diego, and South Lake Tahoe, and the counties of Monterey and Santa Barbara. We ensured that our selection included geographical diversity, local jurisdictions with large and with small populations, local jurisdictions with a high number of state licenses and those with few state licenses, and a variety of permitting processes. Using DCC’s publicly available data of local jurisdictions, we considered only those local jurisdictions that allowed at least one type of cannabis business, such as retail, distribution, manufacturing, cultivation, or testing, to operate within its jurisdiction. We further determined the size of the local jurisdictions allowing cannabis businesses using population census data from the U.S. Census Bureau. We used cannabis sales data from the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration and a DCC supplemental budget report on the total number of active annual and provisional state licenses, by jurisdiction, to identify the local jurisdictions with cannabis sales in quarter four of 2022 and active permits as of March 2023. We gained assurance that the list of local jurisdictions from which we made our selection was complete by using multiple sources of data, such as those referenced above, to verify that those local jurisdictions had cannabis activity and should be considered in the selection.

See relevant information about each jurisdiction and the factors for selection at Table 12.

Recommendations

Under state law, the Legislature may only amend or repeal an initiative statute without voter approval if the initiative statute permits the Legislature to do so. Proposition 64 allows the Legislature to amend certain provisions of the act—including those that protect local jurisdictions’ ability to exercise local control over the authorization and regulation of cannabis businesses—by majority vote as long as the amendments are consistent with and further the stated purposes and intent of the act. As the text box shows, the purposes and intent of the act include ensuring that local jurisdictions have the ability to regulate cannabis businesses. Because of this significant local control, we make our recommendations generally to all local jurisdictions that permit cannabis businesses rather than making recommendations directly to the Legislature.

The Stated Purposes and Intent of Proposition 64 Include the Purpose and Intent to Allow Local Jurisdictions To Do the Following:

- Enforce state laws and regulations for nonmedical cannabis businesses and enact additional local requirements for nonmedical cannabis businesses, but not require that they do so for a nonmedical cannabis business to be issued a state license and be legal under state law.

- Ban nonmedical cannabis businesses.

- Reasonably regulate the cultivation of nonmedical cannabis for personal use by adults 21 years and older through zoning and other local laws.

Source: State law.

All Local Jurisdictions

To prevent favoritism, ensure fairness, and reduce the risk of corruption, all local jurisdictions that permit or plan to permit cannabis businesses should adopt or amend ordinances or policies and procedures to implement the following processes:

- Consider requiring blind scoring as an additional safeguard for competitive permitting processes. Blind scoring involves removing any identifying information about an applicant from application materials before a review.

- Create an appeals process to allow applicants to appeal the denial of their permit application to an impartial decision-maker.

- Require that all individuals involved in reviewing cannabis applications sign impartiality statements or similar documents, asserting that they do not have personal or financial interests that may affect their decisions. In the interest of transparency, consider making the signed impartiality statements or the language used in the impartiality statements available to the public by potentially posting it to the jurisdictions’ websites.

- Require that designated staff at the local jurisdictions review impartiality statements to ensure that staff who review applications do not have personal or business interests that may affect their decisions.

- Require separation of duties or another layer of approval in the permitting process that prevent one person from exercising control over the decision to award a permit.