2023-105 Middle Class Tax Refund Payments

The State Could Improve Its Approach to Future Financial Relief Payments by Addressing Weaknesses From This Program (Release Date: March 2024)

Published: March 7, 2024Report Number: 2023-105

March 7, 2024

2023‑105

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of Middle Class Tax Refund (MCTR) payments. Our assessment focused on the Franchise Tax Board’s (FTB) administration of MCTR payments, and the following report details the audit’s findings and conclusions. In response to high inflation rates and energy prices in 2022, the Legislature and Governor authorized FTB to issue MCTR payments to qualifying recipients. Although FTB planned to make some payments through direct deposit, it also planned to make many payments through prepaid debit cards (debit cards). To facilitate these payments, FTB entered into an agreement with Money Network Financial, LLC (Money Network) that required Money Network to produce and distribute debit cards, provide customer service, and prevent fraud. In general, we determined that the State could improve its approach to issuing future financial relief payments by addressing the weaknesses we identified in the MCTR program.

Although FTB issued MCTR payments relatively quickly compared to similar payment programs in California and other states, FTB’s agreement with Money Network created difficulties related to the administration of the payments. For example, FTB did not ensure that Money Network provided the required level of customer service, because FTB’s agreement with Money Network had no accountability measures for contractor underperformance, short of terminating the agreement. Additionally, the agreement does not define fraud, and Money Network has not tracked fraud in the program adequately enough for the State to know the true rate of fraud.

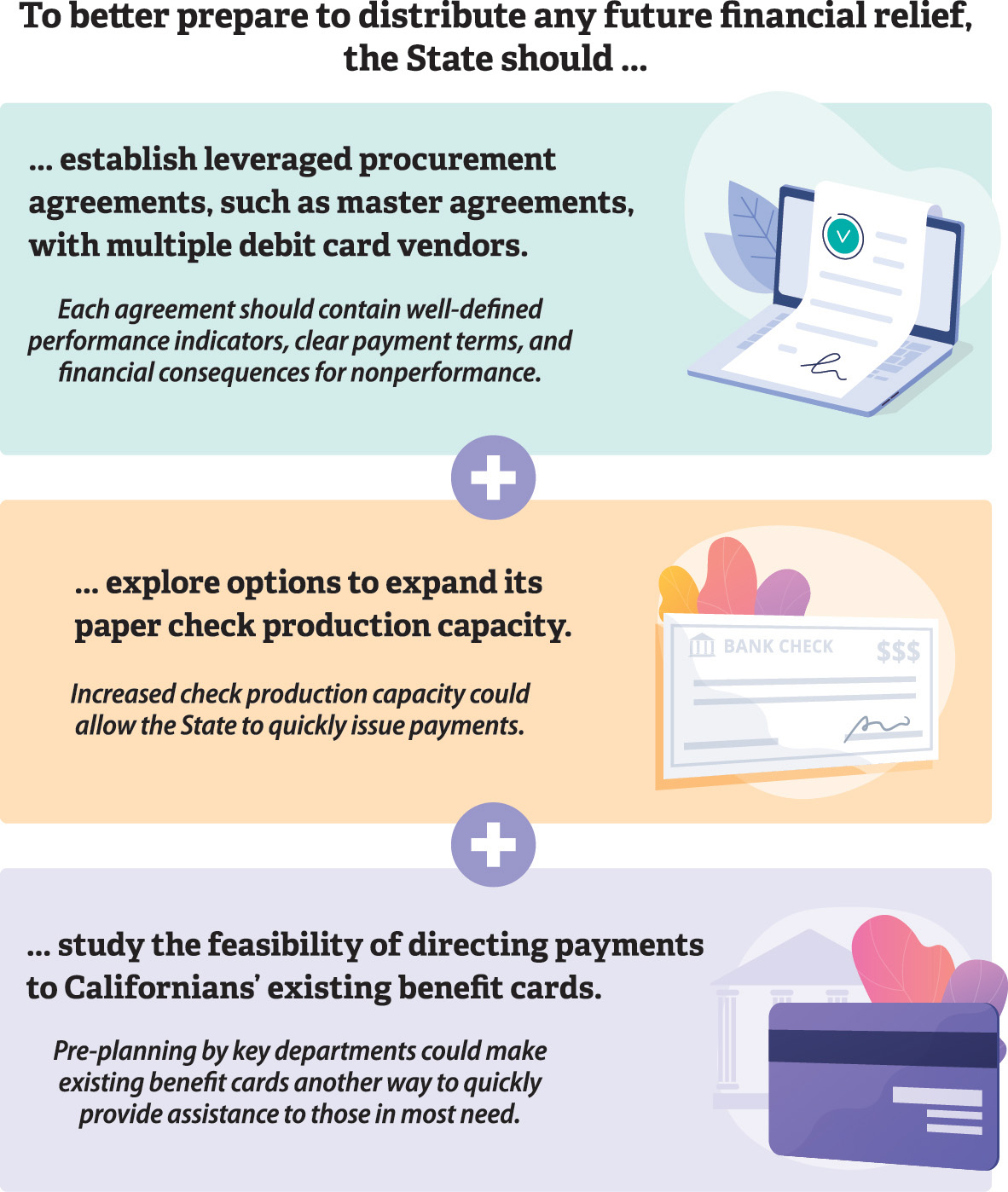

In an effort to distribute financial assistance as quickly as possible, the State selected its vendor and negotiated the agreement with Money Network at a greatly accelerated pace. However, the speed of the procurement likely contributed to the problems we found with the agreement. To avoid similar difficulties when providing financial relief payments in the future, the State should prepare now by establishing master agreements with debit card vendors that include provisions to address the weaknesses in the MCTR agreement. The State should also consider how it could increase its capacity to deliver financial relief payments through using multiple payment methods, including checks and debit cards that already exist for other benefit programs.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ATM | automated teller machine |

| CHHS | California Health and Human Services Agency |

| EDD | Employment Development Department |

| EMV | Europay, Mastercard, Visa |

| FTB | Franchise Tax Board |

| ITN | Invitation to Negotiate |

| IVR | interactive voice response |

| MCTR | Middle Class Tax Refund |

| SCM | State Contracting Manual |

| SCO | State Controller’s Office |

| TTY | teletypewriter or text telephone device |

Summary of

Key Findings and Recommendations

When Californians faced historically high inflation rates and energy prices in 2022, the Legislature and Governor authorized the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) to issue financial relief payments—known as Middle Class Tax Refund (MCTR) payments—to qualifying recipients. To help facilitate these payments, FTB executed a $25 million agreement with Money Network Financial, LLC (Money Network), a vendor that provides financial services. Under the agreement, Money Network is responsible for producing and distributing debit cards and for providing customer service and fraud-prevention services to cardholders. Although FTB issued MCTR payments relatively quickly compared to similar payment programs in California and other states, the provisions of FTB’s agreement with Money Network created certain difficulties related to the administration of the payments. By taking action now, the State could better position itself to avoid similar difficulties when providing financial relief payments in the future.

- FTB did not ensure that Money Network consistently provided the required level of customer service to cardholders. Although Money Network received more than 29 million calls—the vast majority of which were handled by its automated system—Money Network did not answer nearly 900,000 of the roughly two million phone calls from callers seeking to speak with an agent about the MCTR program or issues with their debit cards. Weaknesses in FTB’s agreement with Money Network made holding Money Network accountable for its lack of customer service difficult.

- Although Money Network reported a fraud rate to FTB of less than 1 percent of the amount distributed through debit cards, the State cannot determine the precise level of fraud in the MCTR program because Money Network did not answer a substantial portion of cardholder calls and has not specifically tracked fraud in the program.

- Because the agreement’s payment structure bundles most services into a single per-card rate, FTB paid to Money Network nearly 90 percent of the agreement’s total cost in the first 15 months of the 49-month agreement period. This front‑loaded payment structure does not fully safeguard the best interests of the State. In addition, the agreement with Money Network does not include provisions that would allow FTB to assess agreed-upon liquidated damages if Money Network does not comply with agreement terms—provisions we found in other state agreements for similar services.

- Drawing on this experience, the State should prepare now for future statewide financial relief payments by establishing master agreements with debit-card vendors. Additionally, the State should consider how it can build a stronger capacity to deliver financial relief payments through a variety of payment methods, including checks, direct deposit, and debit cards.

Recommendations

We make several recommendations to better prepare the State for administering future financial relief payments. These recommendations are located on page 39.

Agency Comments

General Services generally agreed with our recommendation to institute master agreements with specific elements and indicated its willingness to incorporate each of the recommendation’s elements if feasible. Although we did not make recommendations to FTB, it disagreed with some of our findings and conclusions.

Audit Results

To Help Alleviate Financial Pressure on Californians, the State Authorized MCTR Payments

Source: State law; FTB’s agreement with Money Network; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index data; U.S. Energy Information Administration retail gasoline price data; U.S. Department of Energy historical gasoline price information; interviews with FTB staff.

SB Figure A Description:

A timeline with three key points shows the early development of the Middle Class Tax Refund program.

First, in early 2022, Californians faced increased financial pressure due to historically high inflation and record-breaking average gas prices.

Next, in June 2022, the Legislature and the Governor authorized financial relief payments to qualified recipients. The figure states that the Franchise Tax Board planned to use direct deposit information from electronically filed tax returns for tax year 2020 to make Middle Class Tax Refund payments via direct deposits. The Franchise Tax Board needed a vendor to distribute payments via debit card to Californians for whom it did not have direct deposit information.

The last portion of the timeline, in July 2022, shows that the Franchise Tax Board signed an agreement with Money Network to provide debit card production and distribution, customer service, and fraud prevention.

By the summer of 2022, the inflation rates for both the U.S. and California had been rising for months, with the national rate having reached a four-decade high. The resulting economic conditions placed pressure on Californians in many ways. Inflation rates for food costs in urban areas of the U.S. at that time were higher than both the national and state inflation rates. Similarly, gas prices in California peaked in June 2022, reaching a record-breaking average of $6.29 per gallon. In response to these financial pressures, the Legislature and Governor enacted the Better for Families Act that same month, authorizing one-time financial relief payments to California taxpayers—commonly referred to as MCTR payments.

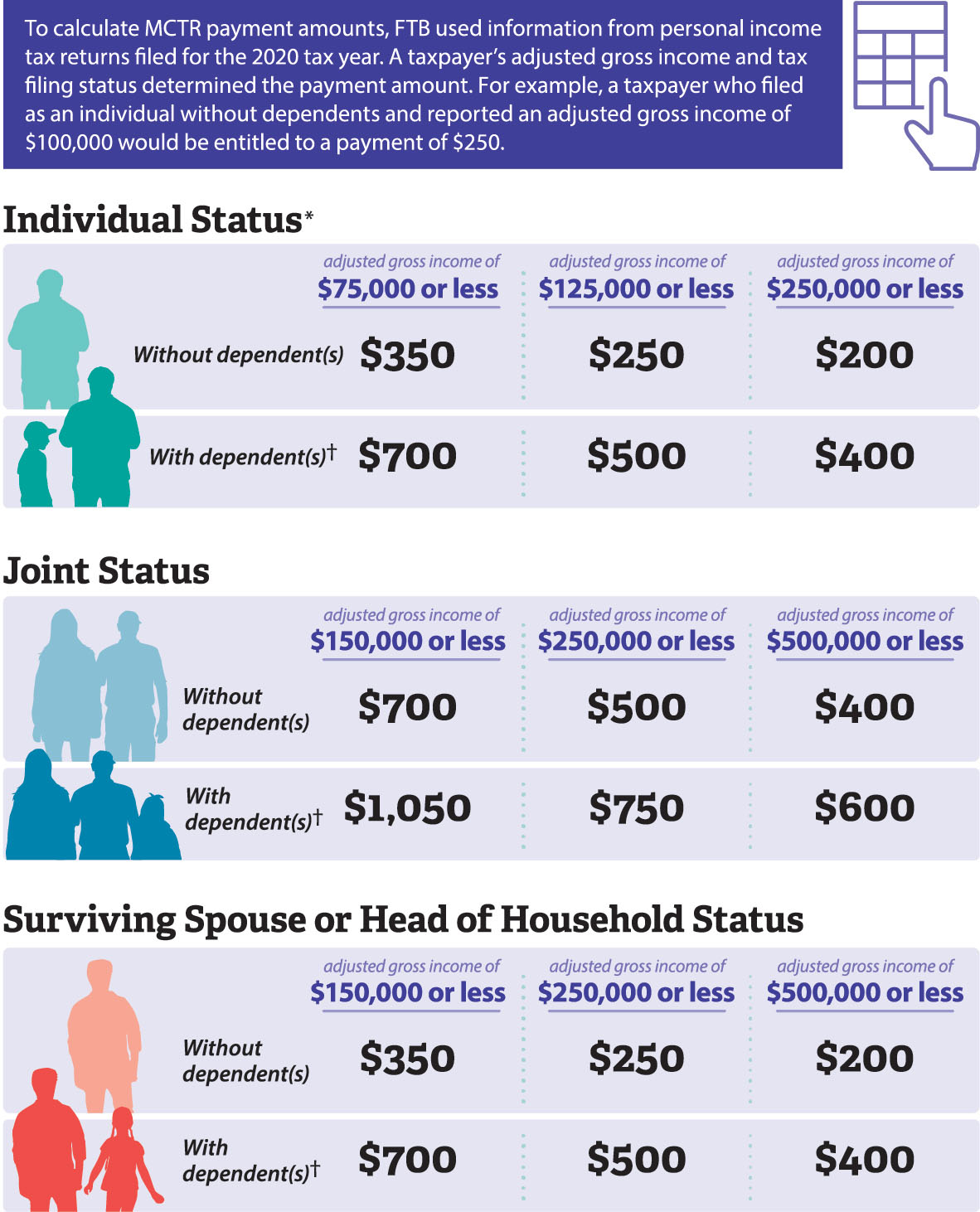

Under the Better for Families Act, FTB is responsible for administering the MCTR program and making payments to eligible recipients. The law specified that FTB must base payment amounts on information from taxpayers’ 2020 personal income tax returns, including their adjusted gross income, their filing status, and whether the taxpayers claimed a dependent. Figure 1 shows the statutory payment amount parameters. The law made FTB responsible for determining the form and manner in which it would provide the payments.

FTB was already responsible for issuing personal income tax refunds, some of which it issues directly to bank accounts through direct deposits. Therefore, when it received responsibility for distributing MCTR payments, FTB already had bank account information for certain taxpayers. According to FTB, this information generally allowed it to issue MCTR payments directly to Californians who had electronically filed their 2020 state tax returns and had received a tax refund for that year by direct deposit.1 Direct deposit recipients represented nearly half of the total MCTR payments, a significant proportion of the overall eligible population.

For the vast majority of the remaining eligible Californians, FTB provided MCTR payments through prepaid debit cards (debit cards) issued by a vendor. FTB and the Department of General Services (General Services) collaborated to procure this vendor. Citing volatile market conditions, General Services began the process by using its statutory authority to procure a vendor through negotiation—a competitive procurement process that state law authorizes General Services to use in circumstances the text box describes. Although General Services advertised the State’s desire to procure a debit-card vendor, FTB selected the vendor. FTB signed an agreement with Money Network—a company that provides financial services—to distribute debit cards, provide customer service, and protect against fraud. The term of this agreement lasts from July 2022 through July 2026, and its maximum value is about $25 million.

Statutory Conditions That Allow General Services to Procure Goods and Services Through Negotiation

General Services may use a negotiation process to enter into an agreement for goods and services under the following conditions:

- The negotiation process can further define the business need or purpose for the agreement.

- Bidders may experience extremely high costs to prepare a solicitation response because of the complexity of the business need or the purpose for the agreement.

- The State knows the business need or purpose for the agreement, but a negotiation process may identify different types of solutions to fulfill the need or purpose.

- The State knows the business need or purpose for the agreement, but a negotiation is necessary to ensure that the State receives the best value or the most cost‑effective goods or services.

General Services cited the last two conditions above as the rationale for using a negotiation process for the MCTR procurement.

Source: State law and an interview with General Services.

Figure 1

MCTR Payment Amounts Varied by Filing Status and Income

Source: State law.

* This category includes individuals who are married and file separately.

† Households with at least one dependent were eligible for a single supplement to their payment, regardless of the number of dependents in the household.

Figure 1 Description:

A heading above the chart explains how the Franchise Tax Board used taxpayers’ adjusted gross income and tax filing status from personal income tax returns filed for the 2020 tax year to determine Middle Class Tax Refund payment amounts. Below that heading, the chart is divided into three categories, including individual status, joint status, and surviving spouse or head of household status. Each category is further broken down by whether or not the household contains dependents. The chart lists payment amounts according to three eligible income levels in each status. Silhouettes on the left-hand side of the chart demonstrate hypothetical household arrangements that correspond to each status.

Specifically, individual status with an adjusted gross income of $75,000 or less may be eligible for a payment amount of $350 if they did not claim a dependent or $700 if they claimed a dependent. Individual status with an adjusted gross income between $75,000 and $125,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $250 without a dependent or $500 with a dependent. Individual status with an adjusted gross income between $125,000 and $250,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $200 if they did not claim a dependent or $400 if they claimed a dependent.

Joint status with an adjusted gross income of $150,000 or less may be eligible for a payment amount of $700 if they did not claim a dependent or $1,050 if they claimed a dependent. Joint status with an adjusted gross income between $150,000 and $250,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $500 if they did not claim a dependent or $750 if they claimed a dependent. Joint status with an adjusted gross income between $250,000 and $500,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $400 if they did not claim a dependent or $600 if they claimed a dependent.

Surviving spouse or head of household filers with an adjusted gross income of $150,000 or less may be eligible for a payment amount of $350 if they did not claim a dependent or $700 if they claimed a dependent; with an adjusted gross income between $150,000 and $250,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $250 if they did not claim a dependent or $500 if they claimed a dependent; with an adjusted gross income between $250,000 and $500,000 may be eligible for a payment amount of $200 if they did not claim a dependent or $400 if they claimed a dependent.

Lastly, the graphic notes that households with at least one dependent were eligible for a single supplement to their payment, regardless of the number of dependents in the household. The graphic also notes that the single status includes individuals who are married and file separately.

FTB Distributed Accurate Payments to Eligible Californians Relatively Quickly

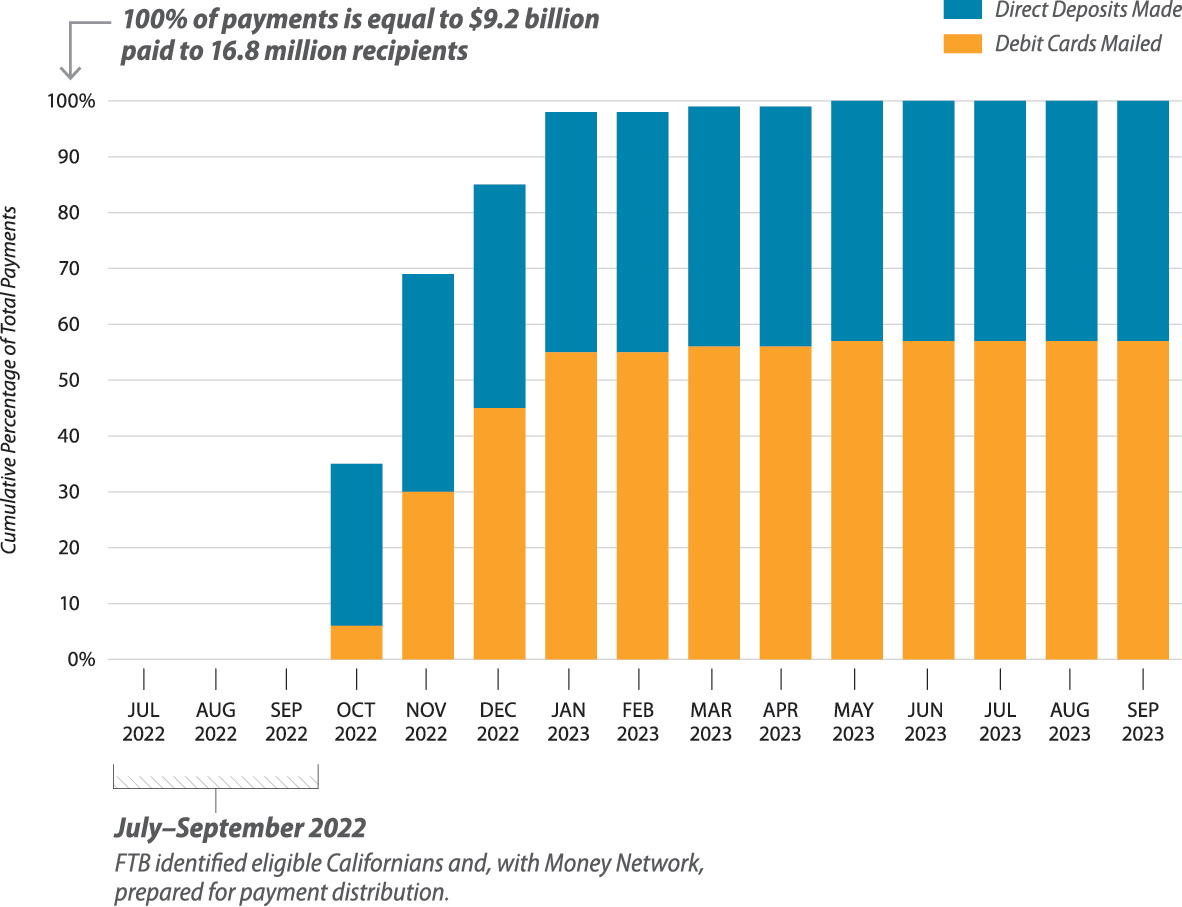

Source: FTB payment data.

Note: This figure does not include the small percentage of payments that FTB issued by paper check. Table A in Appendix A provides a more detailed presentation of payment data.

SB Figure B Description:

The figure is a bar graph that shows the percentage of the total payments made each month from July 2022 through September 2023, broken down further into payment types: debit cards mailed and direct deposit made. The graphic notes that 100 percent of the payments is equal to $9.2 billion dollars paid to 16.8 million recipients.

The graphic shows that the Franchise Tax Board made no payments during the months of July, August, and September 2022. During these months, the Franchise Tax Board identified eligible Californians and, with Money Network, prepared for payment distribution.

In October 2022, the Franchise Tax Board distributed about 35 percent of the total payments with about 30 percent made using direct deposits and 5 percent made using debit cards. In November 2022, the number of payments distributed rises to almost 70 percent with about 30 percent of payments made using debit cards and 40 percent made using direct deposits. In December 2022, about 85 percent of total payments were distributed. Of that 85 percent, about 45 percent of the payments were distributed using debit cards and the remaining 40 percent made through direct deposits. The Franchise Tax Board distributed almost 100 percent of payments by the end of January 2023. After January 2023, the number of direct deposits shows no significant growth and the number of debit card payments grew by less than 5 percent. Overall, about 55 percent of payments were distributed on debit cards, while about 45 percent of payments were distributed through direct deposits.

The figure notes that the graph does not include the small percentage of payments the Franchise tax Board issued by paper check, and that Table A in Appendix A provides a more detailed presentation of the payment data.

FTB generally calculated MCTR payment amounts in compliance with the requirements of the Better for Families Act and generally paid all eligible recipients. To identify eligible recipients, FTB used taxpayer information from personal income tax returns filed for the 2020 tax year to generate a list of filers whose adjusted gross incomes were under the $500,000 threshold for the program. Then FTB verified that these taxpayers met the other MCTR eligibility requirements, including residing in California. Although we found that FTB generally made correct eligibility determinations, we also found that it paid a relatively small number of individuals—108,000 of 16.8 million (less than 1 percent)—who both filed taxes and were claimed as dependents on another tax return. These individuals were ineligible under the terms of the Better for Families Act. We describe this issue in detail in the Other Areas We Reviewed section of this report.

After identifying eligible recipients, FTB calculated the recipients’ MCTR payment amounts using their filing status, adjusted gross incomes, and any dependents they reported on their 2020 tax returns. We used the same taxpayer information—filing status, adjusted gross income, and claimed dependents—and independently calculated the amounts owed to those eligible for MCTR. After comparing the amounts we calculated to those FTB calculated, we determined that FTB had generally calculated accurate amounts for the eligible recipients.

Shortly after FTB signed the agreement with Money Network in July 2022 and before issuing any payments, FTB and Money Network began planning how they would work together to issue MCTR payments by debit card. They included in these planning efforts the design and testing of data formatting to enable FTB to transfer data to Money Network. They completed this process in October 2022, allowing FTB to issue the first payments in that month. The majority of payments that FTB distributed in October 2022 occurred through direct deposits. After that month, however, FTB cumulatively issued about 57 percent of its payments using debit cards. Recipients also had the option to decline the receipt of a debit card and instead receive their MCTR payment through a state-issued paper check. However, these check payments were a small fraction of the overall payments FTB made. By January 2023, four months into payment distribution, FTB had distributed MCTR payments to nearly all eligible recipients. Table A in Appendix A shows the number and amount of MCTR payments that FTB distributed, by month and payment type.

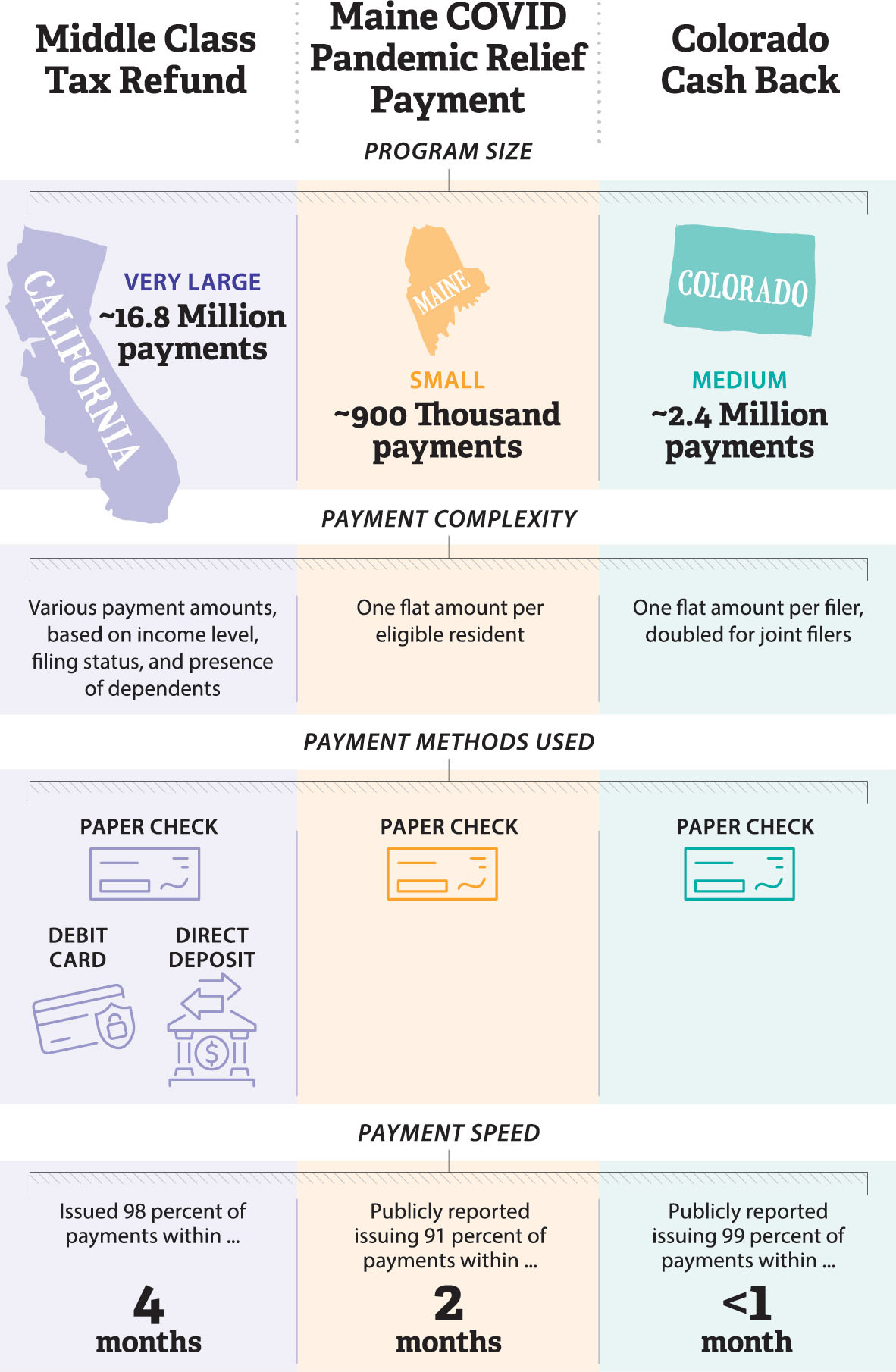

As initially enacted, the Better for Families Act contained no direct payment deadlines, but the Act did require payments to be made as soon as possible. We determined that FTB distributed MCTR payments relatively quickly compared to similar programs throughout the country, after accounting for the complexity of each program. The text box lists the programs against which we compared the MCTR program. These programs are similar to the MCTR program in that they provided financial relief payments sometime in 2021 or 2022. MCTR was more complex than most of these programs because of its large group of recipients, its distribution through three different payment methods, and the variety of its payment amounts. Although the Colorado and Maine programs had faster distribution timelines than did MCTR, they had fewer recipients and fewer payment methods. Figure 2 compares MCTR and those two programs, including the size and payment methods of each program.

Programs to Which We Compared MCTR

- California Golden State Stimulus I and II (two programs)

- Colorado Cash Back Program

- Maine COVID Pandemic Relief Payment Program

- New Mexico 2021 Income Tax Rebate Program

Source: Auditor analysis.

FTB was able to distribute payments as quickly as it did because it avoided technological problems that could have caused delays. When we compared the planned timeline for MCTR payments against system outage reports from FTB, we found that no system outages interfered with the distribution of payments. Further, Money Network stated that it experienced no technological delays in issuing debit cards, and we confirmed that it generally adhered to the distribution schedule from the outset of the MCTR program. FTB explained that during critical times when it was transmitting large volumes of payment-related data to Money Network, the two entities coordinated their efforts and monitored the transfers in real time to ensure that they could troubleshoot any difficulties they faced. Finally, when we reviewed the reasons for delayed payments, we did not identify any payments delayed by technological problems.

Figure 2

A Comparison to Other Relief Programs Shows That FTB Distributed Most MCTR Payments Reasonably Quickly

Source: FTB data; unaudited information from the governor of Maine; unaudited information from Colorado’s governor, legislature, and Department of Revenue.

Although FTB distributed payments relatively quickly to nearly all eligible recipients, it has taken longer to issue payments to some recipients. To determine some of the reasons that FTB paid some individuals later, we selected and reviewed 17 cases in which FTB issued its latest payment in or after June 2023. FTB’s records of these payments show that the two most common causes of the delays were incorrect mailing addresses for some recipients and the time that FTB took to manually review certain payments to ensure recipient eligibility and review for possible fraud.

Nine of the 17 payments we reviewed were delayed by problems with the recipients’ addresses. In some of these nine cases, the debit cards that Money Network sent to the recipients were returned as having been unsuccessfully delivered. To correct incorrect addresses, FTB obtained updated addresses through tax filing documents or the U.S. Postal Service. It also waited for some recipients to update their addresses by contacting FTB. State law generally places responsibility for maintaining up‑to‑date address information on taxpayers, not on FTB. Further, if FTB had attempted to correct these problems by reaching out to taxpayers, it would have faced the logistical challenge of contacting individuals for whom it did not have correct contact information. Therefore, we believe that FTB’s approach to the incorrect address issue was reasonable.

Seven payments in our selection were delayed because of the time FTB spent reviewing the cases for eligibility or possible fraud. The time that FTB took to complete these reviews ranged from about one month to nearly eight months, with most reviews taking about three to four months. According to FTB, it typically needs one month to conduct these reviews. However, FTB also explained that from late April 2023 through early August 2023, it was slower to conduct these reviews because this time frame spanned the typical peak of tax filing season as well as that year’s extended tax filing season. Accordingly, FTB prioritized reviewing tax returns during these months before conducting manual reviews of MCTR payments.

Our work indicates that FTB has made payments to virtually all eligible individuals. Obtaining complete assurance that FTB paid every single eligible individual would have been cost‑prohibitive. Nonetheless, our analysis indicates that the upper limit of the amount of remaining payments is likely approximately $20 million—or 0.2 percent of the total program size—which is attributable to about 40,000 individuals. The predominant reason FTB had not made payments to these individuals is that FTB did not have valid addresses to which to send payments. In some cases, FTB determined—based on earlier attempts to contact the taxpayer—that the address it had on file was incorrect before it attempted to pay an eligible individual. In other cases, FTB made one or more unsuccessful payment attempts and subsequently determined that it had an incorrect address. In July 2023, the Legislature amended state law to require FTB to issue all payments no later than September 30, 2023. However, state law makes an exception to this payment deadline that allows FTB to issue replacement payments after this date. As a result, the individuals with incorrect addresses to whom FTB made at least one unsuccessful payment attempt prior to this deadline may still receive a payment.

FTB informed us that to the extent it receives updated address information from these individuals, it will continue to issue payments, but it will issue those payments by paper check. However, FTB also conveyed its perspective that on or after June 1, 2024, it will no longer be able to make MCTR payments from the Better for Families Tax Refund Fund because of language in state law that redirects any funds in that fund to the General Fund as of June 1, 2024.

Finally, there remain a significant number of debit-card recipients who have yet to activate their debit cards. According to information that Money Network provided to FTB, more than one million debit cards—worth approximately $611 million in payments—had not yet been activated by their recipients as of January 2024. To address this issue, FTB plans to send reminder letters to these cardholders encouraging them to activate their cards. FTB will then assess the impact of these letters on the total number of cards still inactivated.

FTB Did Not Ensure That Money Network Provided the Required Level of Customer Service

Source: FTB’s agreement with Money Network; contact center data that Money Network provided to FTB; Money Network contact center staffing information.

* FTB’s agreement defines level of access as the number of contacts answered out of the total number of contacts offered. In practice, both FTB and Money Network applied this metric only to calls involving callers attempting to speak to a live contact center agent.

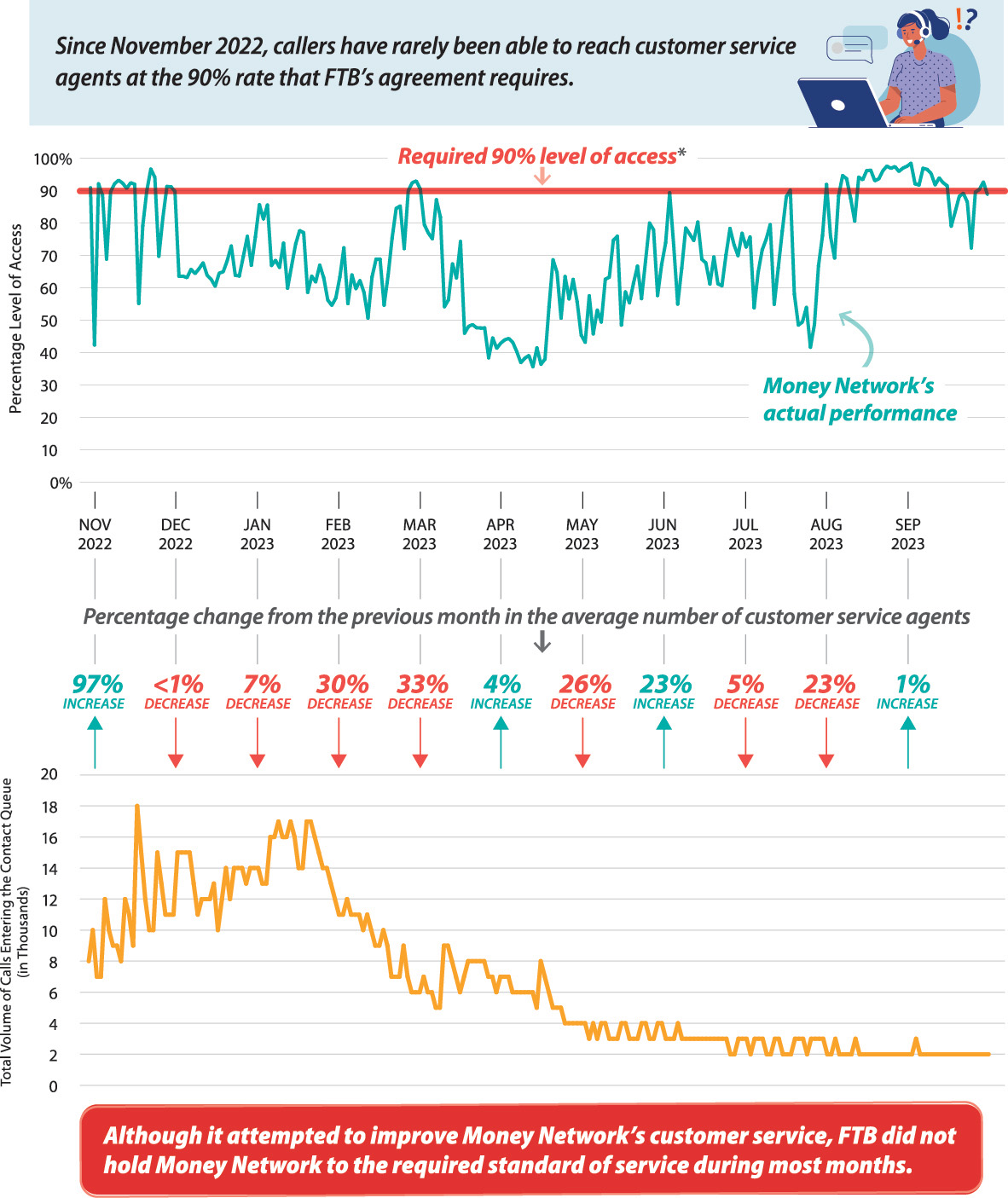

FTB’s agreement with Money Network requires Money Network to provide customer service and support, including self-service and live‑service options such as phone calls and live chat. The agreement refers to these options as contacts and requires Money Network to operate a contact center. Further, the agreement requires Money Network to provide sufficient staff at the contact center to answer at least 90 percent of the contacts offered (i.e. phone calls, live chat)—a metric that the agreement calls the level of access that Money Network provides. In practice, both FTB and Money Network have applied the level-of-access metric only to phone calls coming into the contact center that are directed to a live customer service agent. They have not applied this metric to the other contact options by which MCTR payment recipients may try to communicate with Money Network.

In August 2022, before it distributed any debit cards, Money Network began operating a phone line dedicated to callers who were seeking information about the MCTR program (general inquiry phone line). Coinciding with when it began issuing debit cards in October 2022, Money Network introduced a second phone line meant to assist callers who had issues with their debit cards (debit-card phone line). On both phone lines, a caller initially accessed information or handled tasks—such as activating a debit card, reporting a debit card as lost or stolen, or requesting a replacement debit card—through self-service options on Money Network’s interactive voice response (IVR) system. If callers could not satisfactorily resolve the reason for calls through the IVR, they could choose to transfer to a queue where they would wait to speak with a live customer service agent (contact center queue). Money Network reported to FTB that the two phone lines had received a total of 29.2 million calls from August 2022 through September 2023 and that its IVR system had handled 26.9 million of these calls.

Money Network placed only 1.3 million of the remaining 2.3 million calls in the contact center queue, leaving about one million calls unconnected to the queue. There are three reasons for unconnected calls. One reason is that Money Network received the calls during a time when the contact center was closed. The agreement between FTB and Money Network specifies that the contact center should operate on weekdays from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., with the exception of state holidays. The second reason is that the queue was at times too full to accept additional calls—a circumstance known as deflection. In these cases, a caller would attempt to transfer the call to the contact center queue and then receive a message explaining that due to high call volumes, Money Network could not assist the caller at that time, and encouraging the caller to call back later. Finally, callers may have disconnected from the call in the time between transferring from the IVR and joining the contact center queue.

Due to limitations in the contact center data that Money Network provided to FTB, we could not determine the precise breakdown of calls among each of these three conditions. However, Money Network provided data to us during the audit that indicates from August 2022 through September 2023, 363,000 of the one million calls disconnected during the time between being transferred from the IVR and being placed in the contact center queue. Additionally, those data showed that about 230,000 calls occurred when the contact center was closed. The remaining roughly 360,000 calls were deflected by Money Network’s phone system.2 Because these calls were never placed in the contact center queue, they are not included when calculating the level of access that Money Network provided. Nonetheless, the deflected calls represent a significant gap in Money Network’s ability to handle the volume of calls that it received.

Ultimately, Money Network accepted about 1.6 million calls into the contact center queue. These include the 1.3 million that entered the queue from the IVR and an additional 280,000 teletypewriter (TTY) calls that bypassed Money Network’s IVR system.3 From August 2022 to November 2022, contact center service agents answered 93 percent of the 57,000 calls referred on the general inquiry phone line. However, Money Network’s performance on this phone line declined below the required 90‑percent level after it began distributing debit cards. From November 2022 through April 2023, Money Network answered only 81 percent of the 392,000 calls it placed in the contact center agent queue from the general inquiry phone line.4 More concerning is Money Network’s performance on the debit‑card phone line. From November 2022 through September 2023, Money Network answered only 64 percent—about 720,000—of the 1.1 million calls it received on that phone line. The remaining 405,000 calls disconnected before Money Network could answer the call, presumably because callers abandoned the calls.

During certain periods of the MCTR program, callers experienced long wait times that could have caused them to abandon their calls. Average daily wait times were about 12 minutes from November 2022 through September 2023, but they reached nearly an hour at their peak in April 2023. Money Network explained that many unanswered calls were made by callers who did not wait on hold for long enough to provide a reasonable opportunity for Money Network to answer the call. Specifically, as many as 195,000 calls from October 2022 through June 2023 were disconnected within 60 seconds of being referred to the contact center queue. Money Network indicated that it was common in the call center industry to measure performance using such thresholds. Using the data Money Network reported to FTB, we could not verify Money Network’s assertion about the number of calls abandoned within a 60-second timeframe. However, even after adjusting for these calls, we found that Money Network did not provide a 90-percent level of access, as required by its agreement with FTB.

FTB confirmed that it did not conduct any customer surveys to learn about customers’ experiences with Money Network’s contact center. It indicated that it learned about customer service issues instead through the contact center metrics it received from Money Network and through extensive outreach from stakeholders such as the Legislature, callers to FTB’s taxpayer call center, and the media. This approach is reasonable given the potential costs of a customer survey and the existence of other mechanisms to reveal problems.

In January 2023, FTB took steps to push Money Network to improve its customer service. In that month, FTB agreed to pay Money Network nearly $1.3 million through two work orders with the goal of improving customer service through April 2023. One of these work orders expanded to 10 p.m. the hours the contact center’s phone lines were open, and the two work orders collectively required Money Network to add 36 staff for about a four-month period to those working in the contact center. Additionally, one of the work orders directed Money Network to make adjustments to the IVR to account for questions that recipients may have had about how their MCTR payment related to their taxable income.5

However, these work orders are problematic because, in effect, FTB agreed to pay Money Network additional funds for services that were already assigned a cost in the original agreement. FTB’s agreement with Money Network specifies that staffing for the contact center is included as part of a $1.35-per-card cost that FTB agreed to pay. The agreement requires Money Network to staff the contact center with a sufficient number of staff to achieve the 90‑percent level of access. It also states that Money Network may need to operate the contact center during modified hours if required to do so by FTB, and it does not indicate that the expanded operating hours would necessitate additional payments to Money Network. At the time FTB issued the work orders, it already had an agreement on a cost for services and the expected performance it was supposed to receive for that cost. This raises questions about why the State would agree to pay its vendor more when it was not even meeting its obligations at the original price. According to FTB’s chief financial officer, FTB issued the work orders because it was making every effort to make the best decision, based on available information, for taxpayers, FTB, and the State. As we describe later, FTB’s agreement with Money Network does not contain any direct consequences—short of termination of the agreement—for underperformance in the area of customer service. Accordingly, when FTB needed to prompt Money Network to improve its performance, FTB’s options for doing so were limited by the weaknesses in the agreement. Nonetheless, we are concerned that FTB agreed to spend additional state resources to address poor performance by a vendor that was already obligated to provide a specified level of service.

Moreover, the work orders were not effective at improving Money Network’s performance. Money Network’s level of access did not reach the level required by the agreement, and the average number of staff assigned to the MCTR phone lines began decreasing in January 2023, the same month that Money Network agreed to increase staff levels. The average contact center staffing level generally decreased until June 2023. According to Money Network, staff turnover was the main driver in the declining number of contact center staff. Money Network asserted that it hired more than 140 staff specifically for the MCTR contact center between April 2023 and September 2023, yet the net effect was a decline in the total number of staff because of attrition. However, Money Network’s explanation covers a period primarily after the expiration of the work orders. The level of access Money Network provided from January 2023 through April 2023 averaged just 62 percent, well below the required 90‑percent level.

Ultimately, FTB did not pay Money Network the full $1.3 million pertaining to these work orders. According to FTB’s chief financial officer, FTB observed in Money Network’s reported data that the level of access was not improving, despite FTB’s order for it to dedicate more resources. Invoice and payment records show that Money Network invoiced FTB for the full $1.3 million, and FTB paid only $873,000. FTB’s chief financial officer explained that FTB arrived at its payment amount by reviewing the call statistics during the four-month period covered by the work orders and comparing those statistics to prior months’ call center statistics. When we asked FTB why it did not base its conclusions about Money Network’s contact center on staffing data, FTB stated that it had attempted multiple times to obtain staffing data from Money Network but that Money Network did not provide this information. Although the agreement allows FTB to review any of Money Network’s records directly pertaining to its performance of the agreement, it does not specifically require Money Network to provide FTB with data about the number of contact center agents working in the contact center at a particular point in time.

In August and September 2023, Money Network more consistently achieved a 90‑percent level of access. However, these months overlap with the lowest daily call volumes in the contact center queue since Money Network began operating the debit-card phone line. Call volumes averaged around 2,100 calls per day during these months, compared to the average of 9,200 calls per day that entered the queue on the same phone line during January and February 2023, when Money Network was issuing the last large distribution of debit cards.

The Level of Fraud in the MCTR Program Is Unclear Because of Money Network’s Poor Customer Service and Inadequate Fraud Tracking

Source: FTB’s agreement with Money Network; fraud information that Money Network provided; contact center reports that Money Network provided to FTB for the period from August 2022 through September 2023.

In its activities related to the MCTR program, FTB generally incorporated and followed best practices that the Fraud Risk Management Guide outlines for fraud risk management and mitigation.6 These best practices include performing comprehensive fraud risk assessments to identify fraud schemes and implementing activities to mitigate risk. We observed that FTB monitors tax return activity on an ongoing basis in an effort to identify emerging fraud schemes and possible fraud. Because FTB used information from 2020 tax returns to identify eligible MCTR recipients, it was using information that it had already screened for fraudulent activity. FTB indicated that these reviews included screening for identity theft, which FTB defines as someone else using an individual’s information for an unlawful purpose. Moreover, while identifying the population of eligible recipients, FTB performed additional checks to flag possible fraud for further review and to ensure that only eligible recipients would receive MCTR payments.

Money Network also provided evidence that it generally followed certain best practices for fraud risk management. Best practices for financial institutions’ fraud risk management include deploying and evaluating fraud control activities and using metrics to measure and monitor fraud risk. Money Network deploys and evaluates controls intended to prevent and detect fraud. For example, Money Network designed risk rules that send alerts to staff when suspicious activity is detected on debit cards.7 According to Money Network, it periodically revises these risk rules based on a review of data analytics and metrics to ensure that the rules are effective at identifying possible fraud.

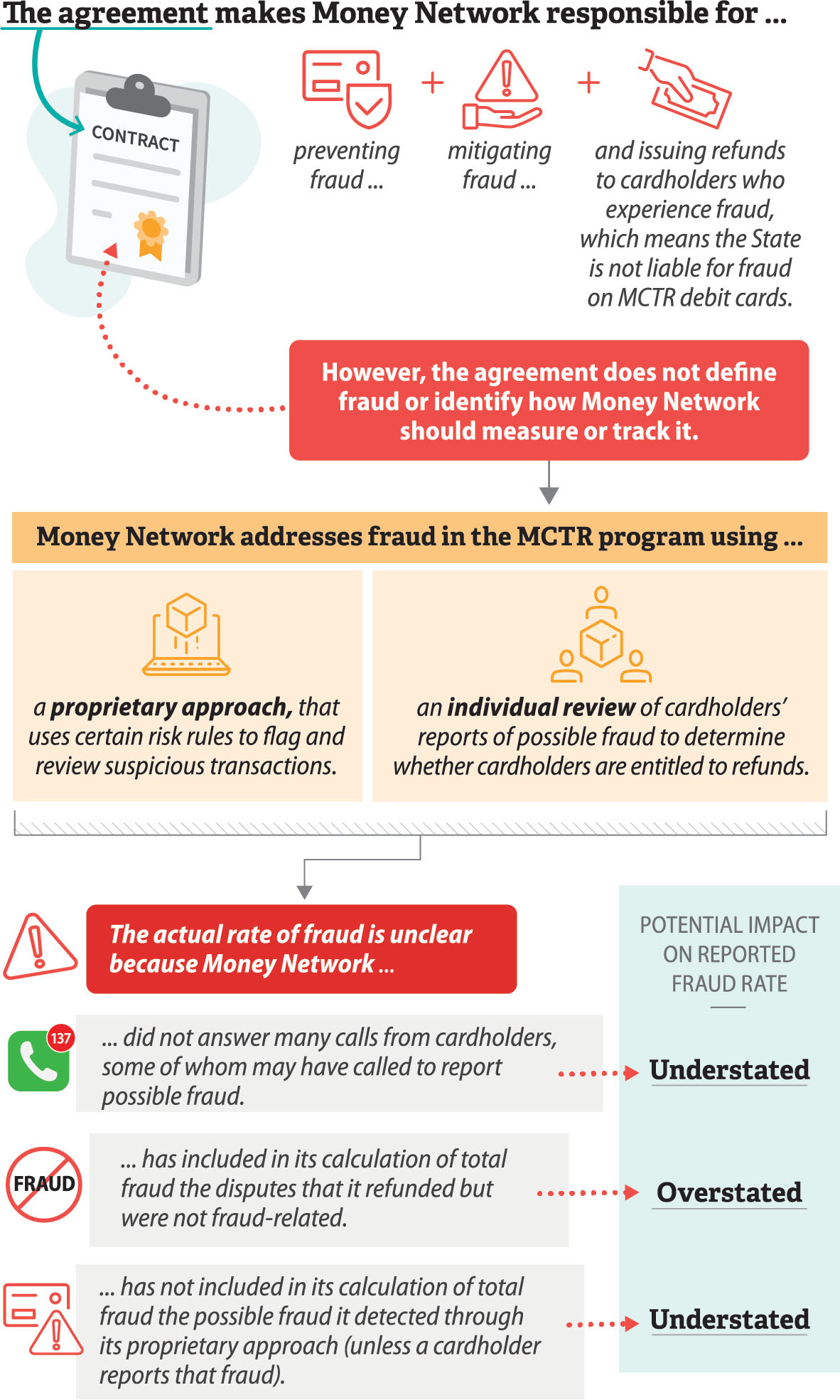

FTB’s agreement makes Money Network, not FTB, responsible for reimbursing cardholders for fraudulent transactions. However, two deficiencies in Money Network’s approach to fraud have hindered the State’s ability to know the true rate of fraud in the program. The first of these deficiencies is the rate of unanswered calls to the contact center. One way that Money Network can learn of possible fraud is through cardholders calling its contact center to report suspicious transactions. These reports are known as disputes. FTB and Money Network have focused on disputes as a measurement of fraud in the MCTR program. However, Money Network did not answer hundreds of thousands of calls from November 2022 through September 2023, and the level of access that Money Network provided to callers was significantly below the required level of 90 percent. Therefore, cardholders who may have experienced possibly fraudulent transactions may have been hindered from reporting them to Money Network, meaning that the total number of reported disputes could underrepresent the true number of suspicious transactions.

Both FTB and Money Network disagreed with our assessment that the rate of unanswered calls affects the measurement of fraud. Each entity asserted that callers who had experienced fraud would continue to call the contact center until they reached a call center agent because they would be motivated to obtain a refund of the money that had been stolen from them. We acknowledge that some callers might persist in calling until they could submit a dispute to Money Network. However, the contact center data indicate that successfully reaching a contact center agent was difficult for a prolonged period following the distribution of the vast majority of debit cards in January 2023. The contact center’s poor performance over this period is reason to doubt that all cardholders with possibly fraudulent transactions reported their problems to Money Network.

The second deficiency is that Money Network has not documented fraud specifically within the dispute records it maintains. Money Network can receive disputes that are not related to fraud. Fraud-related disputes include those that cardholders report when they did not authorize a transaction, while disputes that do not relate to fraud can include cardholder disagreements with merchants over authorized transactions, such as cardholders not receiving items they purchased. The data that Money Network has maintained about MCTR program disputes do not differentiate between these two types of disputes. Money Network stated that it did not separately track fraud-related disputes because the MCTR program is not regulated the same way that other banking activity is regulated. Although Money Network’s agreement requires it to report all fraudulent activity to FTB, the agreement also lacks terms that describe specific financial consequences if Money Network does not provide FTB with this information.

FTB’s agreement with Money Network further complicates any attempts to seek an accurate measurement of fraud. The agreement requires Money Network to prevent fraud at least at a 99‑percent success rate. However, the agreement does not define fraud. In the absence of a definition in the agreement, Money Network defines fraud as the total value of the disputed transactions it has refunded, which overstates the amount of fraud because it includes disputes that are not related to fraud, as we discuss above. Further, that definition excludes fraud that Money Network identifies through its automatic alerts related to suspicious debit-card activity. For example, through its fraud monitoring program, Money Network identified fraud schemes against MCTR cardholders and reported to FTB that it took action to prevent further losses to those cardholders. However, it did not include these cases in its calculations of the total amount of fraud in the program unless the affected cardholders called to report related disputes, which would then prompt Money Network to investigate the disputes. In any future agreements with debit-card vendors, the State should establish a definition of fraud that includes all identified instances of fraud—regardless of how the vendor detected those instances—and excludes any transactions or disputes that the vendor deems are unrelated to fraud.

Notwithstanding the challenges in measuring fraud in the MCTR program, we used the data that Money Network provided on disputes to address the questions we were asked to address as a part of this audit. As of August 2023, Money Network had recorded disputes from about 65,000 cardholders—a small percentage of the total cardholder population of 9.5 million. Table B2 in Appendix B provides income‑related information about these cardholders. We obtained the fraud rate that Money Network reported to FTB in June 2023 and observed that it was less than $51.4 million, or 1 percent of the amount distributed through debit cards at that time, which is below the level that the agreement requires Money Network to keep fraud. Because of the concerns about measuring fraud that we describe earlier, and because both FTB and Money Network asserted that more precise information about the amount of reported fraud is confidential, we do not disclose the exact amount of fraud that Money Network reported to FTB.

Money Network informs cardholders that it may take up to 90 days to resolve a dispute. Using data that Money Network provided on disputes, we found that Money Network resolved within this time frame 93 percent of the disputes that it either reimbursed or closed without reimbursing. Table 1 shows the length of time Money Network took to reach conclusions about the disputes that it had resolved, through the beginning of August 2023. In addition, Money Network had about 13,500 disputes that it had not yet resolved as of that time.

The MCTR Agreement Does Not Adequately Safeguard the Best Interests of the State

Source: FTB’s agreement with Money Network and card distribution data.

*EMV stands for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa. EMV chip cards are credit, debit, or prepaid cards that have an embedded microchip that securely stores data and provides an additional layer of security when the user inserts the chip card to complete a transaction.

SB Figure E description:

The figure shows a clipboard with a paper on it titled “Agreement Cost Terms” and below that are two columns: one for items and one for costs. The list of items includes program management, EMV chip surcharge, reminder letter with postage, tax form with postage, and priority replacement for lost or stolen cards. Associated costs for each item, respectively, are $1.35 per debit card for program management, $0.50 per EMV chip for EMV chip surcharge, $0.68 for reminder letter with postage, $0.68 for tax form with postage, and $8 per reissuance (if requested by Franchise Tax Board) for priority replacement for lost or stolen card. At the bottom of the clipboard is an image of two people shaking hands.

The graphic calls out program management, which includes services such as card production and distribution, customer service, and fraud prevention. We note that Franchise Tax Board generally paid Money Network the full program management cost up front after Money Network’s distribution of debit cards, despite Money Network’s ongoing responsibility to provide program management services.

At the bottom of the figure, the graphic indicates that the total agreement value is $25.3 million. Then, pursuant to the agreement, Money Network issued debit cards relatively early in the agreement period. As a result, Franchise Tax Board had paid 89 percent of the total agreement value as of October 2023—$22.5 million—limiting its ability to hold Money Network financially accountable for services that Money Network must provide through July 2026.

We note that EMV stands for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa, and that EMV chip cards are credit, debit, or prepaid cards that have an embedded microchip that securely stores data and provides an additional layer of security when the user inserts the chip card to complete a transaction.

In keeping with the general guidance in the State Contracting Manual (SCM), FTB’s agreement with Money Network contains specific information about the duration of the agreement, the maximum amount payable to Money Network, and the services that Money Network agreed to provide. The agreement also generally contains the standard provisions that General Services advises all state contracts include. Nonetheless, to the detriment of the State and MCTR recipients, the agreement is marked by two issues that have hindered and will likely continue to hinder FTB’s ability to hold Money Network accountable for its performance.

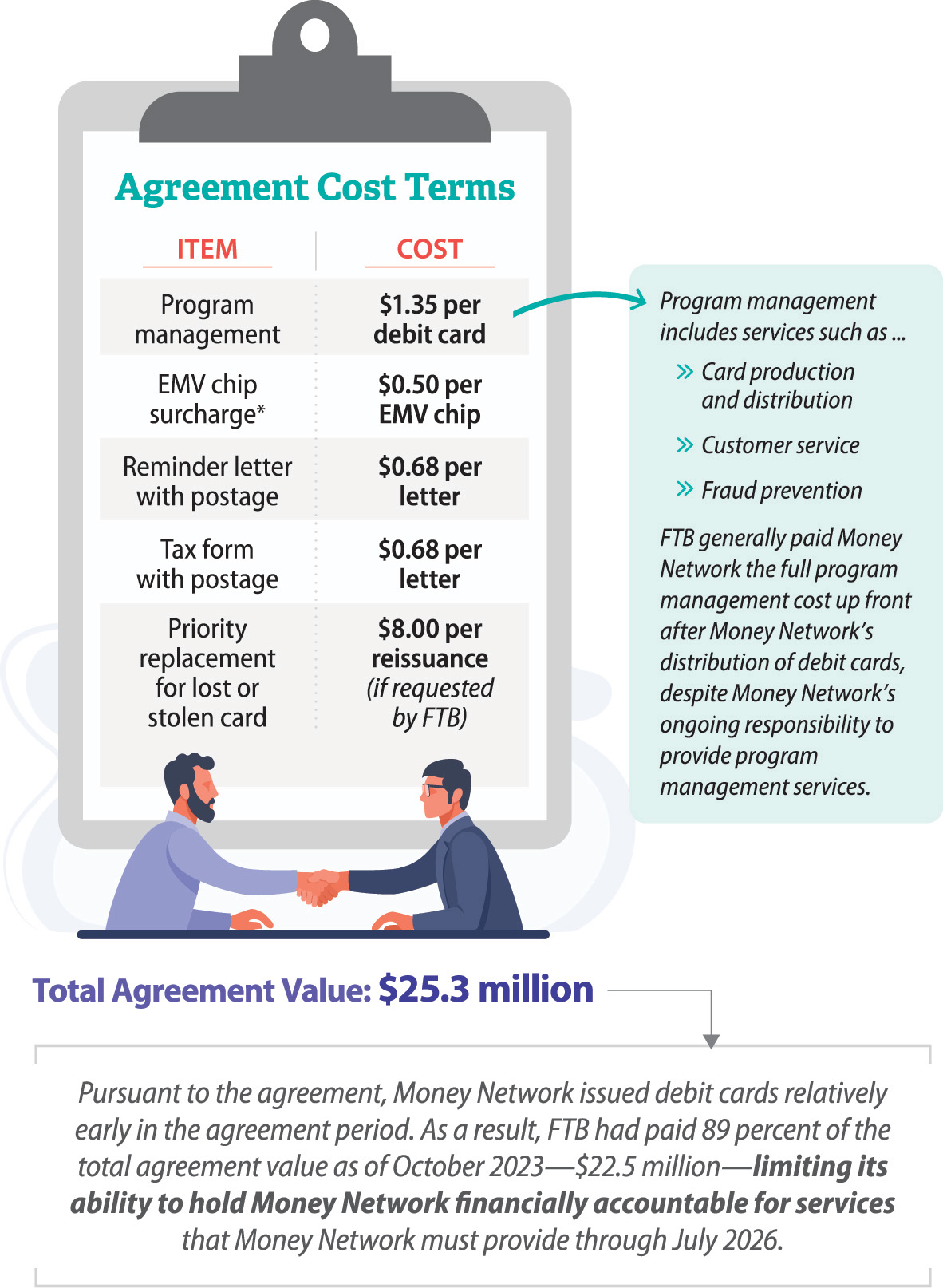

The first issue hindering accountability is the agreement’s payment structure. The agreement combines payment for most services that Money Network agreed to provide into a single, per-debit-card rate. Specifically, FTB agreed to pay Money Network $1.35 per card in exchange for program management services, which includes card production, card distribution, customer service, and fraud-prevention services, among others. About 59 percent of the total $25.3 million agreement is attributable to this per-card rate. The remaining agreement value is for other goods and services.

Because the majority of debit-card production and distribution occurred quite early in the agreement period, the payment structure led FTB to pay Money Network a significant amount of money in the early portions of the period. As of October 2023—15 months into the 49-month agreement period—FTB had paid Money Network $22.5 million of the $25.3 million total agreement amount, or about 89 percent. Of that $22.5 million, $14.1 million related to program management costs, while the other $8.4 million related to the following: the January 2023 work orders; the production and distribution of tax forms (Form 1099-MISC) and reminder letters; a surcharge for debit cards with EMV chips; and sales tax. The distribution of nearly all debit cards early in the agreement period occurred by design: the agreement required Money Network to produce a plan to mail approximately 95 percent of debit cards within a period of 8 to 10 weeks beginning in late October 2022.

However, FTB made these payments before important ongoing services—such as fraud prevention and customer service—had been substantially provided by Money Network, because the agreement bundled these services rather than itemizing the costs and making payment contingent on Money Network demonstrating that it had provided the services. In other words, FTB paid Money Network before Money Network had provided all of the services included in the program management cost of $1.35 per card. As we describe later, the MCTR agreement is exempt from state contracting law and General Services’ oversight. However, as a best practice, the SCM warns against advance payments, stating that departments shall not make payment in advance of receiving goods or the performance of services. Therefore, the payment structure in FTB’s agreement represents a significant limitation in FTB’s ability to protect the State’s interests.

Both General Services and FTB indicated that had FTB sought a different payment structure, it could have risked not attracting a vendor. FTB’s chief financial officer also indicated that doing so could have risked raising the overall cost of the agreement. The filing division chief similarly explained that FTB believed that the bundled payment structure in the agreement is typical of the payment models that debit-card vendors generally use and that asking vendors to adopt a payment model that required them to disclose costs instead of bundling could have increased the price of the services. We acknowledge that each of the other four proposals that the State received in response to its solicitation contained a pricing structure similar to the one included in the Money Network agreement in that none of those proposals separately charged the State for fraud-prevention services. However, each of these four proposals offered to provide customer service—such as call center support—without bundling, demonstrating that the vendor market was not uniform in this regard and that the State had other options available for its consideration.

Further, bundling services together under a single price (e.g., $1.35 per debit card) eliminates transparency around how much each service costs, limiting a department’s knowledge of the costs for each service individually. The lack of clarity especially hindered FTB when Money Network submitted an invoice for debit cards that it had not mailed. The payment provisions of FTB’s agreement assume that FTB will pay Money Network for at least 11 million debit cards. Despite having issued cards for only about 9.5 million accounts through May 2023, Money Network invoiced FTB for $1.2 million in early June 2023 for the cost of producing 1.4 million unissued debit cards. FTB’s chief financial officer stated that FTB chose to pay Money Network for these unissued cards in part because the agreement does not contain terms that clearly prohibit this payment.

However, we found the agreement’s payment terms do not clearly indicate how much of the $1.35 per-card program management cost FTB should pay Money Network for unissued cards. In the absence of clear cost information, FTB processed payment using Money Network’s determination that the cost for an unissued card was $0.84 per card. Had the agreement included itemized costs for the goods and services included in the $1.35 per-card cost, FTB could have used the agreement—rather than a determination by its contractor—to determine how much it should have paid Money Network for unissued cards.

When we discussed our conclusions about the $1.35 per-card cost with FTB, it explained its belief that this cost did not include certain services, such as customer service, and that Money Network provided these services at no cost to the State. FTB believed that the per-card cost was limited to the production and distribution of debit cards. Accordingly, FTB believed that our conclusions about advanced payment and payment for undistributed cards were incorrect and lacking context. We do not agree with FTB’s perspective. FTB said that it only began viewing the agreement’s payment terms in this manner more than a year into the agreement term. Before that, FTB explained that it understood, since the agreement’s inception, that the $1.35 per-card cost covered program management costs, including customer service. In addition, the plain language of the agreement makes it clear that FTB agreed to pay for program management services—including customer service and fraud prevention—as part of the $1.35 per-card cost.

The second issue hindering accountability is the absence in the agreement of any direct consequences—short of termination of the agreement—if Money Network failed to provide the required services. We compared FTB’s agreement with Money Network to two other state agreements for debit cards: an agreement between the Employment Development Department (EDD) and Bank of America and an agreement between the California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHS)’ Office of Systems Integration, and Fidelity Information Services.8 Both of these agreements allow the State to address deficiencies in vendors’ performance by assessing liquidated damages in cases in which the vendor did not meet requirements in the agreements. For example, EDD’s agreement with Bank of America set forth a process that allowed EDD to assess Bank of America damages of $12,000 per day if the bank fails to meet required customer service levels.

Although we found that FTB’s agreement was comparable to the EDD and CHHS agreements in some areas—such as handling expired debit cards and security requirements for contractors—FTB’s agreement lacks explicit provisions for liquidated damages or similar provisions that FTB could use in cases where Money Network does not perform according to the agreement terms. In fact, Money Network has not met the required customer service levels over the course of the agreement. However, the agreement does not include terms that enable FTB to readily withhold payment or to request payment back from Money Network. The lack of such provisions inhibits FTB’s ability to improve the vendor’s performance.

FTB’s filing division chief explained that FTB did not include in the agreement a liquidated damages provision related to customer service because it believed the provisions in the agreement sufficiently protected FTB’s interests in the case of a breach of the agreement. However, he also stated that FTB has learned many lessons while it has managed the Money Network agreement and that, in the future, FTB will give more consideration to whether a liquidated damages provision should be included to further protect FTB’s interests. The filing division chief emphasized that the agreement provides FTB with the right to terminate it in the case of a material breach. Under this provision, the State would be entitled to recover from Money Network any excess costs for acquiring the deliverables and services that Money Network failed to perform. However, terminating the agreement with Money Network is an extreme remedy to underperformance that would leave the State, at least temporarily, without a vendor to provide support to MCTR recipients. Further, in contrast with the liquidated damages provisions that we observed in the other agreements we reviewed, FTB’s agreement contains little detail regarding what constitutes a material breach relative to the specific goods and services that Money Network must provide.

Fast Procurement and Negotiations Likely Contributed to Inadequate Agreement Terms

General Services and FTB were both part of the process of procuring the MCTR agreement. As we described earlier, state law authorizes General Services, under certain circumstances, to use a negotiation process to enter into agreements rather than use other procurement approaches, such as a request for proposals. General Services has greater flexibility under this negotiation authority than state departments would normally have when procuring a vendor. In planning for the MCTR procurement, General Services expected that it would use its authority to negotiate agreements to secure a debit-card vendor. In addition to General Services’ authority to negotiate, the Legislature and the Governor provided FTB with a limited exemption from all state contracting law and from General Services’ oversight when they adopted the 2022 Budget Act on June 27, 2022.

These procurement allowances created a situation in which the MCTR procurement was not subject to the same requirements to which it would otherwise have been subject and in which General Services and FTB had the authority to follow the procurement approach that they determined would best align with the State’s needs. Nonetheless, General Services and FTB took steps that aligned with many of the practices that would normally be part of a competitive procurement for services. For example, General Services announced the opportunity for vendors to express interest in bidding on the MCTR agreement in the California State Contracts Register, received responses from interested bidders, and produced a report summarizing the vendor selection process. In addition, FTB evaluated the proposals using the six scoring criteria it had developed for the procurement, which the text box lists. FTB ranked Money Network’s proposal the highest among the five bidders’ proposals in all but one of these six areas—Money Network’s proposal related to the implementation timeline was ranked second‑highest.

MCTR Procurement Evaluation Criteria

FTB developed the following six criteria to evaluate and score the proposals that vendors submitted for the MCTR agreement:

- Implementation timeline

- Fraud and security

- Debit card and customer service solution

- System integration

- Company experience

- Preliminary cost estimates

Source: FTB procurement documents.

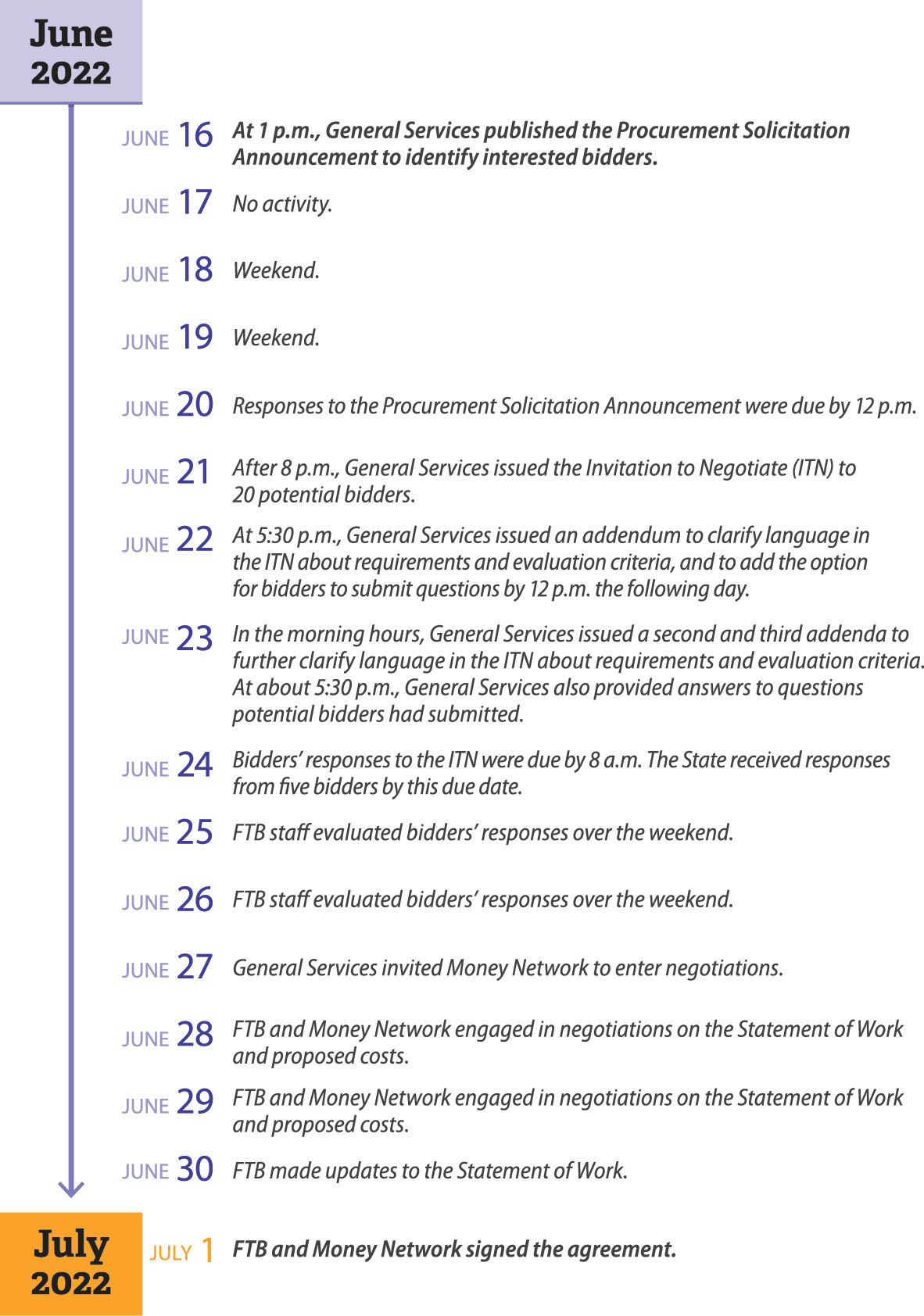

To expedite the issuance of MCTR payments, General Services and FTB significantly departed from standard procurement practices in one area: the time they took to complete the procurement. As Figure 3 shows, General Services and FTB completed the procurement process in fewer than three weeks. In doing so, they may have limited the competitiveness of the MCTR procurement and narrowed the options that FTB had to choose from when it selected its vendor. Under normal circumstances, state law and SCM prescribe a minimum length of time that certain steps in a competitive procurement must last. For example, state departments must advertise bid opportunities in the California State Contracts Register for at least 10 working days to give potential bidders notice, which would give potential bidders time to consider and submit their proposals. In contrast, General Services advertised the opportunity for interested vendors to receive the solicitation document for the MCTR agreement for only a two‑working-day period before sending the Invitation to Negotiate (ITN)—which in this instance served as the solicitation document—to the 20 vendors that expressed interest in receiving the solicitation and possibly participating in the procurement. In other words, General Services reduced by 80 percent the length of time that an advertisement about a state contracting opportunity would normally have been required to be posted.

Figure 3

The State Procured a Vendor for the MCTR Program in Only 15 Days

Source: General Services’ and FTB’s procurement documents.

Figure 3 Description:

The timeline began on June 16, 2022, at 1 p.m., when General Services published the Procurement Solicitation Announcement to identify interested bidders. The timeline then shows that no activity occurred on June 17 or over the weekend of June 18 through 19. On June 20, responses to the Procurement Solicitation Announcement were due by 12 p.m. On June 21, after 8 p.m., General Services issued the Invitation to Negotiate to 20 potential bidders. On June 22, at 5:30 p.m., General Services issued an addendum to clarify language in the invitation to negotiate about requirements and evaluation criteria, and to add the option for bidders to submit questions by 12 p.m. the following day. On June 23, in the morning hours, General Services issued a second and third addenda to further clarify language in the invitation to negotiate about requirements and evaluation criteria. At about 5:30 p.m. on that same day, General Services also provided answers to questions potential bidders had submitted. On June 24, bidders’ responses to the Invitation to Negotiate were due by 8 a.m. The State received responses from five bidders by this due date. Over the weekend of June 25 through 26, Franchise Tax Board staff evaluated bidders’ responses. On June 27, General Services invited Money Network to enter negotiations. On both June 28 and 29, the Franchise Tax Board and Money Network engaged in negotiations on the Statement of Work and proposed costs. On June 30, the Franchise Tax Board made updates to the Statement of Work. The last entry in the timeline shows that on July 1, 2022, the Franchise Tax Board and Money Network signed the agreement.

SCM also states that departments must document all changes to solicitations in addenda that they must issue at least five days before the final bid due date. General Services significantly departed from this requirement by issuing two of its three addenda to the ITN the day before the bid due date. These two addenda modified the ITN’s evaluation criteria. In particular, one of these addenda notified bidders that they would be assessed on a new evaluation criterion: preliminary cost estimates. Such brief turnarounds limited the time that potential bidders had to adjust their responses to remain competitive for the State’s consideration.

FTB’s chief financial officer stated in an email before the procurement announcement that the State would need to begin working with a vendor by the first or second week in July 2022 to implement the infrastructure necessary to issue debit-card payments by December 2022. We acknowledge that the State was trying to expedite financial relief to Californians and that General Services and FTB had the authority to accelerate the procurement. Nonetheless, providing appropriate time for potential bidders to consider opportunities and tailor their responses to meet the State’s needs is a sound practice and can foster competition. In fact, federal acquisition guidance indicates that time constraints can limit a government’s bargaining power during negotiations, particularly if a vendor has substantial business alternatives. Additionally, governments may improve competition and thus gain bargaining strength by postponing the award of an agreement to seek other sources that can provide the necessary goods or services. Therefore, shortening the time provided for vendors to respond to the initial advertisement and to react to changes to the ITN may have disadvantaged the State.

When we discussed our concerns about the procurement’s speed with General Services, the State’s chief procurement officer stated that the procurement’s speed reflected the urgency of the matter, and that General Services merely accelerated, but did not eliminate, any required steps in the procurement process. She also asserted that the five vendors who submitted on-time proposals represent a relatively high number of bidders to establish competition, and she noted that general state contracting laws and policies for awarding state department contracts require a minimum of three bidders to establish competition. Nonetheless, as we note above, the acceleration of certain procurement steps limited the time that potential bidders had to adjust their responses, which may have impacted the quality of their responses. Further, by accelerating the procurement, the State may have discouraged additional bidders from submitting proposals that could have strengthened the choices available to the State.

After determining that Money Network was the highest-rated bidder, FTB negotiated the agreement with Money Network in only two days, providing only a short window of time to ensure that the State obtained optimal agreement terms. The inclusion of a provision in the agreement allowing fees illustrates a consequence of this time constraint. When the procurement was advertised, the statement of work included a complete prohibition against the vendor’s charging MCTR recipients fees for card activation or transactions. Money Network did not propose any changes to that section of the statement of work in its original bid. However, according to FTB’s chief financial officer, Money Network informed FTB during contract negotiations that it wanted to collect fees for certain types of transactions. FTB’s chief financial officer indicated that FTB changed the proposed agreement language to allow Money Network to charge these fees because there was not enough time to fully understand the issue. By doing so, FTB forwent the opportunity to negotiate with Money Network about fees or engage with other bidders to see whether they could provide services without fees—something that three of the other bidders had indicated that they could do. As a result, cardholders were subject to fees that they may not have been otherwise.

Another issue with FTB’s agreement is also likely the result of the expedited procurement. Money Network is required under the agreement to prevent fraud at a success rate of at least 99 percent. However, during negotiations with Money Network, FTB added language to the fraud-prevention section of the agreement that conflicts with the 1 percent fraud rate also in the agreement. This additional language states that Money Network’s “basis points for fraud shall be two basis points or less.”9 This language indicates that the fraud rate shall be no higher than 0.02 percent, which is a far more stringent requirement than 1 percent. The chief of FTB’s filing division stated that FTB added this language to the agreement in error. We confirmed with both FTB and Money Network that they have used the 99 percent fraud-prevention metric when evaluating the amount of fraud related to MCTR debit cards.

Our review of other agreements for similar services demonstrates that FTB’s agreement also lacks strong terms regarding customer service. Specifically, the EDD and CHHS agreements we reviewed include explicit requirements that limit how long customers may wait on hold before a customer service agent answers their calls, and the EDD agreement also includes the requirement that no customer may be automatically disconnected from the call queue. By including more clearly defined terms in the agreement related to the provision of these services, FTB could have better communicated its expectations to Money Network and positioned itself to hold Money Network accountable in the event that the vendor could not meet those expectations.

MCTR Debit-Card Fee Amounts Are Reasonable, but the State Should Consider the Equity of Charging Fees in Future Payment Programs

Source: MCTR debit card fee schedule; fee schedules of five other debit card programs; Money Network fee data; FTB taxpayer data; reports from the following entities: HR&A Advisors Inc., an economic development, public policy, and real estate consulting firm; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; the Legislative Analyst’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Commerce; and the Pew Research Center.

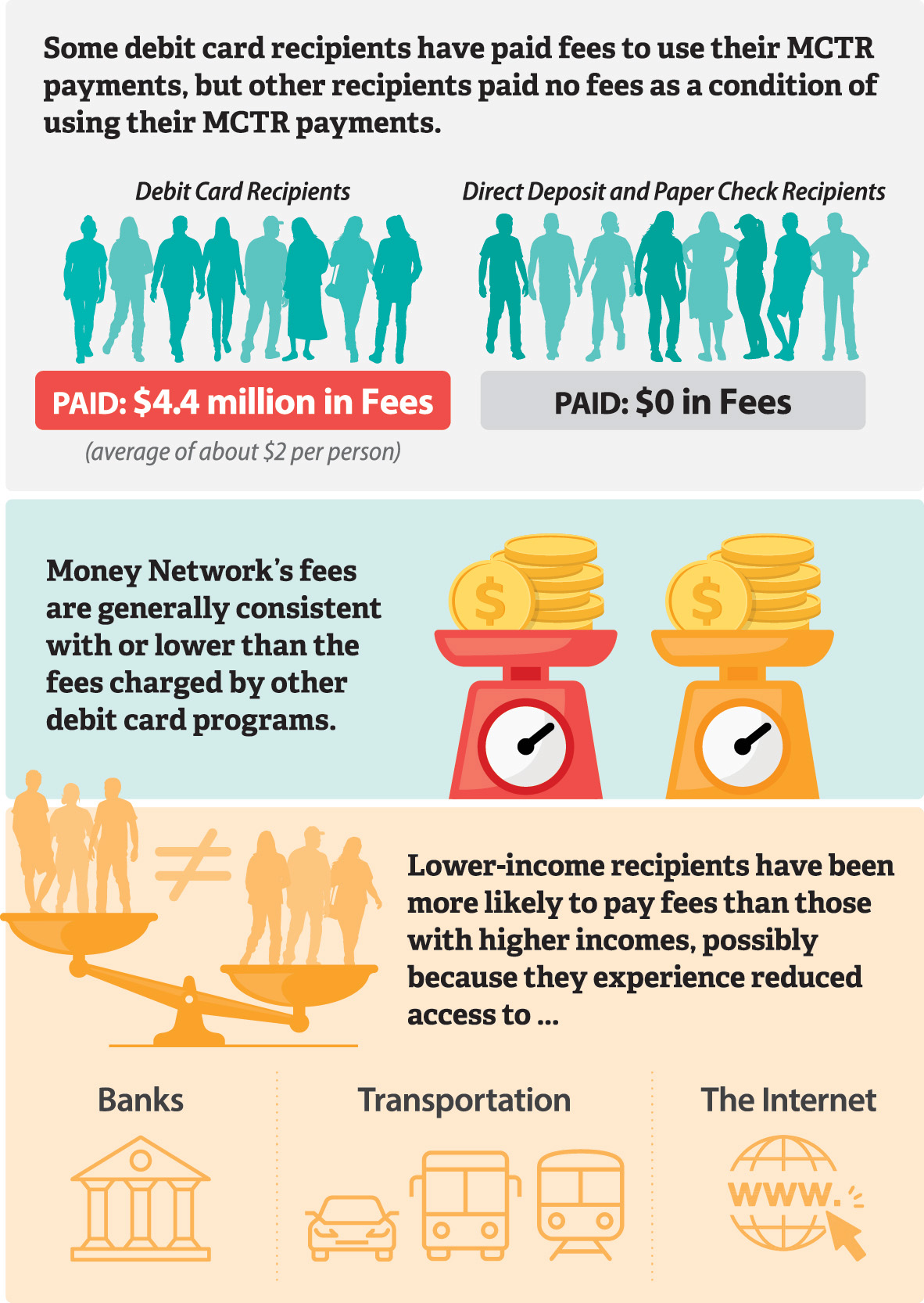

SB Figure F Description:

The graphic first states that debit card recipients have paid fees to use their Middle Class Tax Refund payments, but other recipients paid no fees as a condition of using their Middle Class Tax Refund payments. Two groups of people are depicted: The group on the left is labeled debit card recipients and states that this group paid $4.4 million in fees, or an average of about $2 per person. The group on the right is labeled direct deposit and paper check recipients. This group paid no fees.

The graphic then shows an image of two equally balanced scales, each holding the same number of coins. Next to the scales, the graphic states that Money Network’s fees are generally consistent with or lower than the fees charged by other debit card programs.

Lastly, the graphic shows an unbalanced scale with two groups of people on it. One group of people is raised higher on the scale than the other group, with a “does not equal” sign between them. The graphic states that lower-income recipients have been more likely to pay fees that those with higher incomes, possibly because they experienced reduced access to banks, transportation, and the internet, with icons depicting these three items.

As of mid-July 2023, recipients of MCTR debit cards had collectively paid more than $4 million in fees to Money Network for specific transaction types, such as out-of-network automated teller machine (ATM) transactions and international transactions. The Better for Families Act does not prohibit fees from being charged to MCTR recipients, and FTB’s agreement with Money Network allows Money Network to charge certain types of fees. Table 2 shows the number of accounts affected by fees and the total amount of fees that MCTR recipients paid, by fee type.

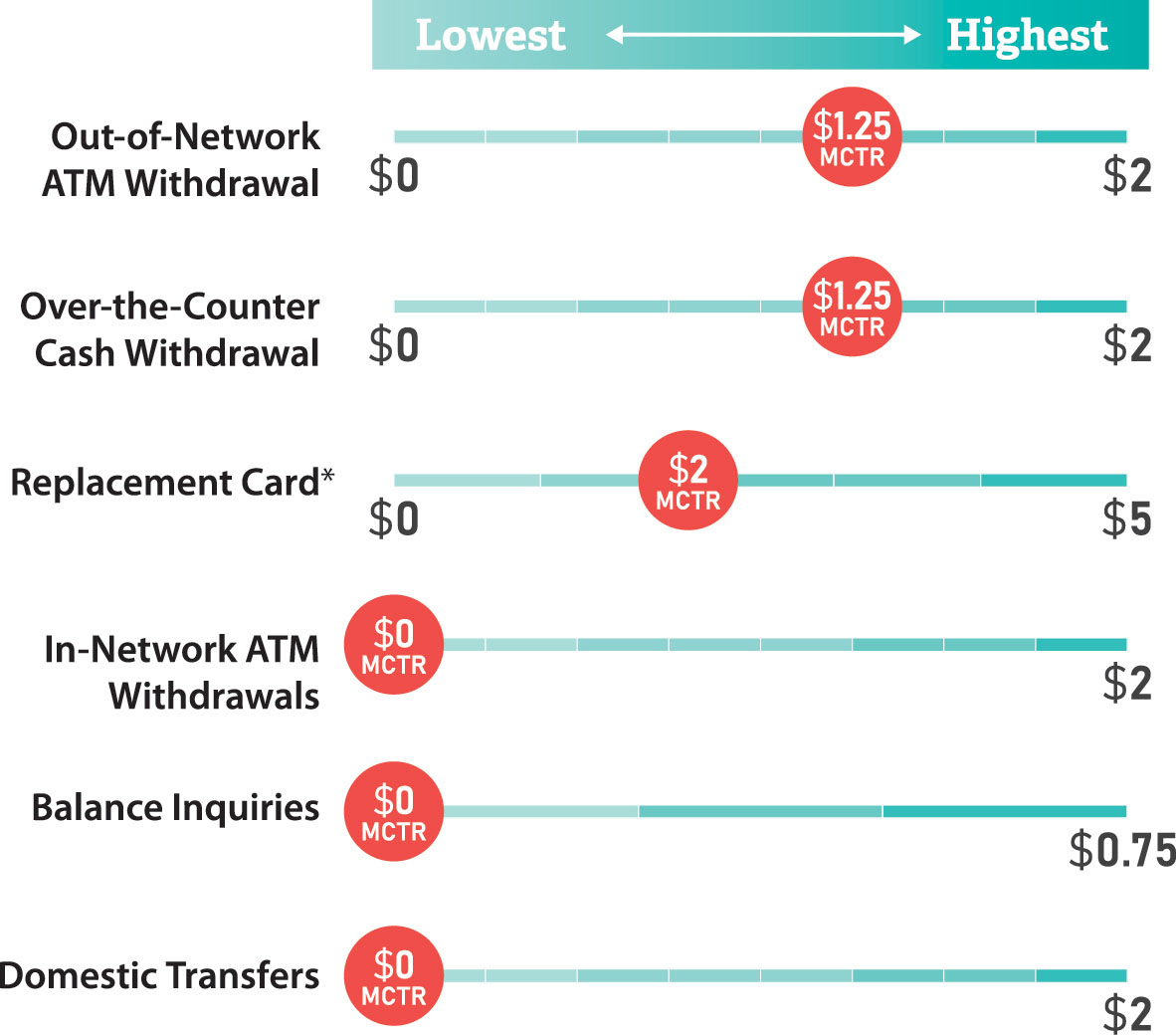

The debit-card fees that Money Network charges MCTR cardholders are reasonable. We compared the fees Money Network charged MCTR debit-card recipients to the fees charged in other debit-card programs, as the text box shows. Money Network charged transaction fees that were generally consistent with fees charged by other debit-card programs. Figure 4 shows the comparison of some of Money Network’s MCTR debit-card fees to fees charged by other card providers.10 Further, individual fee amounts were relatively small. The majority of the fees were associated with out-of-network ATM and over-the-counter cash withdrawals and were typically charged in increments of $1.25 per transaction, which is less than 1 percent of even the smallest MCTR payment amount ($200). The total amount of fees that Money Network charged to MCTR recipients represents less than 0.1 percent of the total MCTR funds distributed using debit cards.

Other Cards and Programs That We Used to Assess the Reasonableness of MCTR Fees

- Citizens Bank of West Virginia MOCA Cash card

- Mississippi Unemployment Benefits

- Akimbo Now Mastercard

- U.S. Bank Reliacard, Pennsylvania State Workers’ Insurance Fund

- U.S. Treasury Department Direct Express Mastercard

Source: Fee schedules and related documentation for each program.

Cardholders had several options to avoid Money Network’s fees. For example, they could make purchases and request cash back without paying fees at participating merchants who accepted Visa debit cards. Similarly, they could use in-network ATMs to avoid ATM fees. Money Network established a MCTR website that provides information about how to activate and use the debit card, including an in-network ATM locator that allows cardholders to search near their location and find surcharge‑free ATMs. Cardholders could also transfer funds to a bank account of their choice after activating their cards.

Regardless of the reasonableness of the specific fees that Money Network charges, the State should consider the equity of cardholder fees when deciding how to operate future debit‑card-based financial relief programs. Only MCTR recipients who received debit cards were required to pay fees as a precondition of using their MCTR payment in certain ways. Although recipients of direct deposits and paper checks may have paid fees when trying to use their payments, those fees were charged by a financial institution of their own choice, rather than by the State’s vendor.

In addition, of those MCTR recipients who received debit cards, a significantly higher percentage of recipients with low incomes paid fees than did recipients with higher incomes. Understanding precisely why this pattern occurred is difficult, given the many ways that recipients could choose to use their MCTR payments. However, we identified a few factors that may have contributed to lower-income recipients’ being more likely to pay fees. First, lower-income recipients are more likely not to have bank accounts, limiting their options for free transfers of their MCTR payment. Additionally, transportation to fee-free ATMs may have been more difficult for lower-income individuals. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, individuals who do not own a vehicle represent 7 percent of households in the State and tend to have lower incomes. Finally, the specific locations of fee-free ATMs were primarily available online, and information from the federal government and the Pew Research Center suggests that lower-income households have less access to the Internet. When considering future economic relief payments, the State should consider the likelihood that those in the greatest need of financial relief may be the people most affected by fees associated with debit cards.

Figure 4

Money Network MCTR Debit‑Card Fees Are Generally Reasonable Compared to the Fees That Five Other Card Providers Charged

Source: Fee schedules for Money Network’s MCTR program; Mississippi Unemployment Benefits card; Pennsylvania State Workers’ Insurance Fund card; U.S. Treasury Department Direct Express Mastercard; Akimbo Now Mastercard; and Citizens Bank of West Virginia MOCA Cash card.

*Money Network waives the fee for a MCTR recipient’s first two replacement cards.

Figure 4 Description:

We note that EMV stands for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa, and that EMV chip cards are credit, debit, or prepaid cards that have an embedded microchip that securely stores data and provides an additional layer of security when the user inserts the chip card to complete a transaction.

The first bar represents out-of-network ATM withdrawal fees. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $2. The Middle Class Tax Refund program fee was $1.25.

The second bar represents over-the-counter cash withdrawals. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $2. The Middle Class Tax Refund program fee was $1.25.

The third bar represents replacement card fees. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $5. The Middle Class Tax Refund program fee was $2. A footnote explains that Money Network waves replacement card fees for the recipient’s first two replacement cards.

The fourth bar represents in-network ATM withdrawals. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0, which is also the fee charged in the Middle Class Tax Refund program. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $2.

The fifth bar represents balance inquiries. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0, which is also the fee charged in the Middle Class Tax Refund program. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0.75.

The sixth bar represents domestic transfers. The lowest amount charged by any program for this fee was $0, which is consistent with the Middle Class Tax Refund program. The highest amount charged by any program for this fee was $2.

Figure 4 Description:

The graphic includes six separate bars. Each bar corresponds to a different fee. The left side of each bar identifies the lowest cost for that fee charged by any of the six programs we reviewed. The right side of each bar identifies the highest cost for that fee. A red circle displaying the fee amount for Middle Class Tax Refund debit cards is placed on each bar, showing how high or low the fee is in relation to fees in the other programs.