2023-103 The Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program

The Lack of Usage Data Prevents the State From Knowing How Often Medi‑Cal Members Receive Perinatal Care

Published: February 15, 2024Report Number: 2023-103

February 15, 2024

2023‑103

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (perinatal program), which is dedicated to reducing the number of children born at low birthweights. Our assessment focused on the oversight of the program conducted by the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services) and the Department of Public Health (Public Health), and the following report details the audit’s findings and conclusions. In general, we determined that the State has provided limited oversight of the perinatal program and has not significantly improved it.

In California, the percentage of infants born at low birthweights—below 5 pounds, 8 ounces—increased from 6.7 percent in 2014 to 7.3 percent in 2021. Infants born at a low birthweight are 20 times more likely to die than infants born at a healthy weight and are more likely to face other health challenges. In 2021 there were about 30,000 infants born in California at low birthweights who face such increased risk.

We found that neither Health Care Services nor Public Health provide the perinatal program with sufficient oversight. Specifically, although Health Care Services requires the managed care plans it contracts with to conduct reviews of each of their primary care providers at least every three years, in 2022 only 45 of the approximately 2,600 providers’ reviews included an assessment of the perinatal program’s services. Public Health delegated its oversight of the perinatal program to local health jurisdictions, but it did not require that those jurisdictions complete the quality assurance chart reviews that would have provided insight into service quality. Our survey of the State’s 61 local health jurisdictions found that 22 jurisdictions did not complete the chart reviews.

In addition to these oversight issues, the State lacks data on the perinatal program’s utilization necessary for its improvement. The data limitations we faced were so significant that we were only able to assess the program’s usage for 14 percent of Medi-Cal members in 2022. Without data and increased oversight, the perinatal program is unlikely to improve.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| CalAIM | California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal |

| CPSP | Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program |

SUMMARY

Results in Brief

The Legislature established the Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (perinatal program) in 1984, which provides enhanced medical services to pregnant and post‑partum Medi‑Cal members. These services include health education, nutrition education, and mental health assessments and interventions. The program’s purpose is to reduce maternal and infant illness and death. State law vests authority for the perinatal program with the Department of Public Health (Public Health). However, a different state department—the California Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services)—is responsible for Medi‑Cal and contracts with managed care plans, requiring them to provide perinatal services comparable to the perinatal program’s care. Public Health administers the perinatal program as offered through fee‑for‑service plans. Neither department provides sufficient oversight to ensure that Medi‑Cal members receive program services or that providers and Medi‑Cal members are educated about the program.

The Perinatal Program Can Improve Low Birthweights

A primary indicator of infant mortality is low birthweight—weights under 5 pounds, 8 ounces. In California, the percentage of infants delivered with a low birthweight is rising, from 6.7 percent of infants born in 2014 to 7.3 percent—about 30,000 infants—born in 2021. The World Health Organization reports that infants with low birthweights are 20 times more likely to die than infants born at a healthy weight. Further, such infants are more likely to face health challenges including respiratory ailments, heart conditions, diabetes, and high blood pressure. The perinatal program offers services that, if used by Medi‑Cal members, can be critical in improving birthweights.

The State Lacks Data to Track the Provision of Perinatal Program Services

The perinatal program has significant data limitations that prevented us from determining how often services are provided. Managed care plans are not required to use billing codes specific to the perinatal program when reporting to Health Care Services the services provided to Medi-Cal members. Although similar codes exist, such codes are not exclusive to pregnancy related services. For example, 39 of the 55 billing codes Health Care Services identified as similar to codes that some perinatal program providers use could also be used for any member and therefore could indicate non‑perinatal program services, such as an initial health assessment for pregnant or non-pregnant Medi‑Cal members. The fee‑for‑service component of the program—which makes up approximately 1 percent of Medi‑Cal members as of 2024—also lacked sufficient data, in part because Public Health did not collect reviews of medical charts performed by Perinatal Service Coordinators (local coordinators). Although the data limitations are significant in terms of identifying the number of Medi‑Cal members who use services provided by the perinatal program, we identified steps—such as conducting reviews of the providers who render program services and beginning to collect information mandated by state law—that the departments and managed care plans can take to improve data related to perinatal services.

The State Lacks Data for Evaluating the Perinatal Program Services Provided

In addition to a lack of data collection, Health Care Services and the managed care plans it oversees also perform inadequate review and oversight of perinatal services. Health Care Services requires managed care plans to conduct a quality assurance review of each of their primary care providers (provider review) at least every three years to ensure that the providers are delivering care in the manner required. However, because Health Care Services’ provider reviews are limited to primary care providers, perinatal service providers who do not serve as primary care providers, which may include Obstetrician/gynecologists (OB-GYN), are often omitted from these reviews. As a result, many providers of perinatal services in managed care plans who do not serve as primary care providers do not undergo the provider reviews that are an important form of provider oversight. For example, only 45, or 1.7 percent, of the approximately 2,600 provider reviews that managed care plans performed in 2022 included any review of services provided through the perinatal program. Limited monitoring, coupled with a lack of program usage data, means that the State cannot determine whether Medi‑Cal members are receiving the program services as defined in state law nor can it evaluate the effectiveness of those services.

Similarly, Public Health does not exercise oversight of the perinatal program. Although state law tasked Public Health in 2007 with the overall oversight and monitoring of the perinatal program, the department has historically relied on local health jurisdictions’ voluntary oversight of fee‑for‑service providers.1 Public Health allows but does not require local health care jurisdictions to conduct chart reviews of perinatal fee‑for‑service providers. However, we found that few such reviews have occurred. Of California’s 61 local health jurisdictions, 22 reported that they did not perform any provider chart reviews from 2018 through 2022,2 and 17 of those 22 jurisdictions said they did not have any active providers during that time. However, we could not confirm whether their assertions were correct, because Public Health does not maintain a complete list of active fee‑for‑service providers. The remaining five jurisdictions reported that they had not performed chart reviews primarily because of staffing limitations and the effects of the pandemic. We also found that the number of completed chart reviews declined in the 38 jurisdictions that reported conducting them, from an average of 13 reviews performed in 2018 to an average of just five in 2022. Overall jurisdictions reported conducting 730 chart reviews in 2018, which decreased to a total of 290 in 2022. Public Health explained that it was aware of limited resources at the local level and therefore did not require that chart reviews occur; it also did not collect information from those reviews that did occur to conduct its own analysis. As a result, the fee‑for‑service component of the perinatal program was effectively left without State oversight during our audit period.3 In late 2023, Public Health decided that the fee‑for‑service component of the perinatal program would no longer receive local reviews because of its small size. Health Care Services estimates that the fee‑for‑service component of Medi‑Cal will represent about 1 percent of Medi‑Cal members during 2024. Public Health plans to replace local oversight with a provider-verified survey, a strategy that we note will decrease already minimal oversight and will rely on unverified self‑certifications.

The Perinatal Program Requires Additional Outreach to Members

Health Care Services should improve its outreach and communication to Medi‑Cal members about the services offered through the perinatal program. Federal regulations require managed care plans to provide their members with a handbook that must describe the benefits that the plan provides, and offer instructions on how to access services and benefits. We reviewed 10 managed care plans’ member handbooks and the template that Health Care Services provides to managed care plans and found that although the handbooks mentioned some services similar to perinatal program services, they did not describe the full range of enhanced services available through the perinatal program. For example, the handbooks note the availability of general mental health services but not the complete mental health assessment required by the perinatal program, which includes intervention and treatment directed toward helping the patient understand and deal effectively with the biological, emotional, and social stresses of pregnancy, with referrals where appropriate. By not informing Medi-Cal members of the comprehensive perinatal services available to them, those members may not have been sufficiently aware of the perinatal program to make use of its services effectively. Health Care Services has responded that the description of the perinatal program is an area that can be improved, adding that it has historically delegated promotion of the perinatal program as well as other public health initiatives to local health departments. However, Health Care Services also agrees that as the role of managed care plans has expanded, the role of member handbooks in communicating benefits to members is now more critical.

See our recommendations for improving the perinatal program in these areas.

Agency Comments

Public Health generally agreed with our recommendations and indicated actions it would take to implement them. Although Health Care Services did not clearly state whether it agreed with all of our recommendations, it indicated that it will take appropriate actions to implement them.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Comprehensive perinatal services are critical to increasing positive maternal and infant health outcomes. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that environmental conditions—such as a person’s birthplace, financial resources, and access to health care—affect rates of preterm birth and maternal mortality. ACOG recommends that providers of perinatal services assess the sufficiency of housing, nutrition, and employment and make referrals to social services to help improve patients’ abilities to meet these basic health needs. For example, ordering tests for or discussing the importance of good nutrition with a person experiencing poor weight gain during pregnancy would provide limited benefit if the underlying condition of food insecurity were not addressed. Similarly, when providers identify a lack of stable housing, ACOG recommends that the providers make appropriate referrals to social services to remedy the condition.

A primary indictor of infant mortality is low birthweight—weights under 5 pounds, 8 ounces. In California, the percentage of infants delivered at a low birthweight has risen from 6.7 percent of infants born in 2014 to 7.3 percent—about 30,000 infants—born in 2021, the most recent year for which we have data. The World Health Organization reports that infants born with a low birthweight are 20 times more likely to die than infants born at a higher weight. Further, infants born with a low birthweight are more likely to experience health challenges, such as respiratory ailments, heart conditions, and feeding difficulties, and they are more likely to live with chronic health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

The California Department of Health Services was the precursor agency to Health Care Services and Public Health. Between 1979 and 1982, that agency conducted a pilot project—the Obstetrical Access Project—in 13 California counties. The project found that the early provision of pregnancy-related nutrition, health education, and psychosocial services could reduce the incidence of low birthweight from 7 percent for the comparison group down to 4.7 percent, or a reduction of 2.3 percentage points.

The Perinatal Program

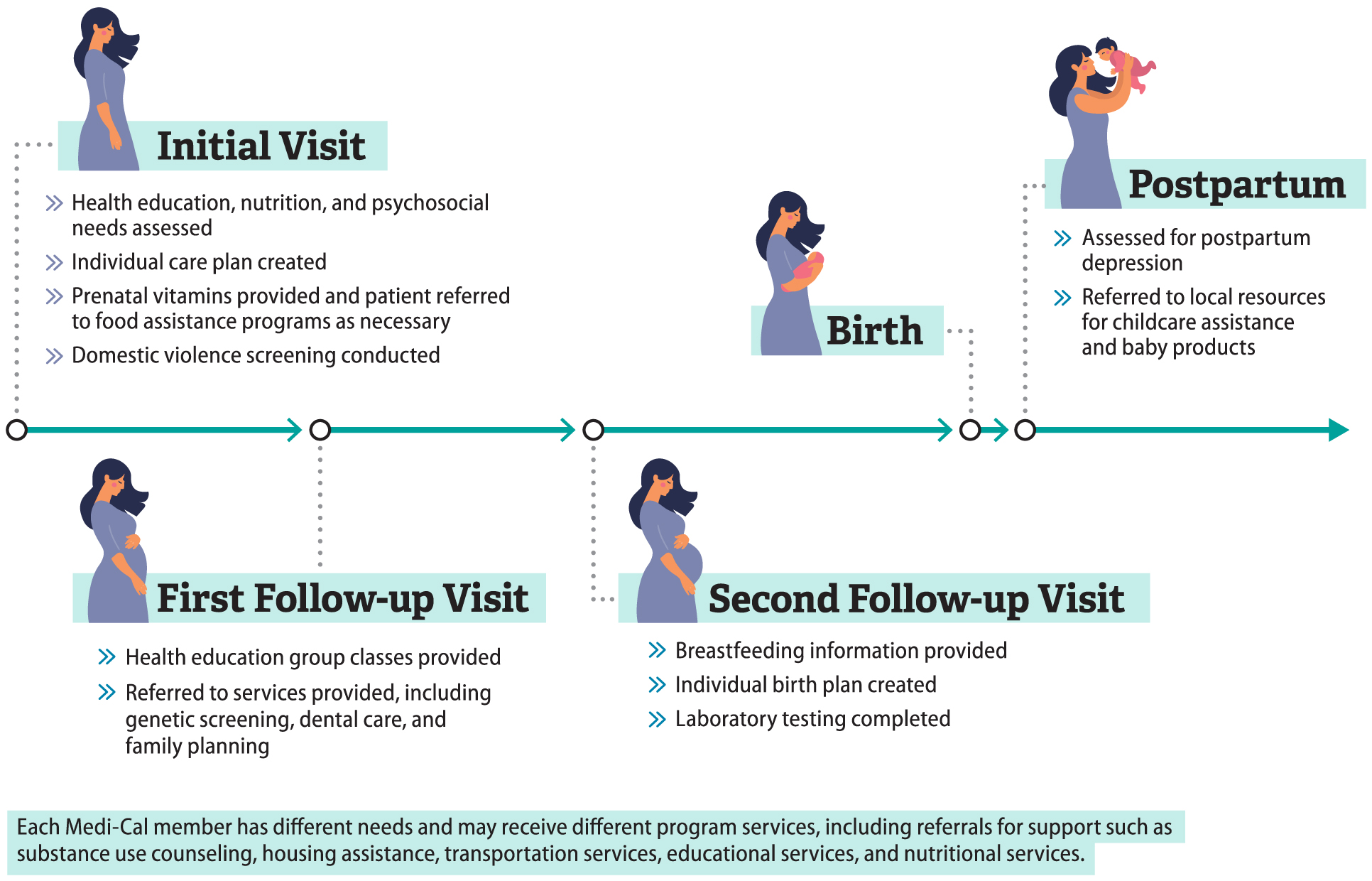

In 1984 the Legislature established the Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (perinatal program) to provide pregnant members of the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi‑Cal) with a comprehensive set of perinatal services. In addition to standard obstetrics care, the perinatal program includes enhanced services intended to reduce maternal and infant illness and death. These enhanced services include health education, nutrition counseling, and psychosocial services. State regulations require that perinatal program service providers (providers) assess Medi‑Cal members for perinatal program services, create individualized care plans, and then provide members with or refer members to appropriate services, such as those noted in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Some of the Critical Services a Medi‑Cal Member Might Receive Through the Perinatal Program

Source: Program guidance and provider protocols.

Figure 1 description:

Figure 1 is a timeline showing some of the critical services a member might receive under the perinatal program. The timeline events include initial visit, first follow-up visit, second follow-up visit, birth, and postpartum. The services described under the initial visit include: health education, nutrition, and psychosocial needs assessed, individual care plan created, prenatal vitamins provided and patient referred to food assistance programs as necessary, domestic violence screening conducted. The services described under the first follow-up visit include: health education group classes provided, referrals to services provided, including genetic screening, dental care, and family planning. The services described under the second follow-up visit include: breastfeeding information provided, individual birth plan created, laboratory testing completed. There are no services described under birth. The services described under postpartum include: assessed for postpartum depression, referred to local resources for childcare assistance and baby products. A note below the timeline states that each member has different needs and may receive different program services, including referrals for support such as substance use counseling, housing assistance, transportation services, educational services, and nutritional services.

Physicians and clinics may provide services through the perinatal program if the provider holds a valid Medi‑Cal provider number and is approved to provide perinatal care. Certain providers may also employ the services of perinatal practitioners (practitioners), as the text box notes. Providers conduct an initial assessment for each enhanced service and offer reassessments each trimester during pregnancy and as necessary after birth.

Practitioners who can provide perinatal program services:

- Physician

- Certified Nurse Midwife

- Registered Nurse

- Nurse Practitioner

- Physician’s Assistant

- Social Worker

- Health Educator

- Childbirth Educator

- Dietician

- Comprehensive Perinatal Health Worker

- Licensed Vocational Nurse

- Licensed Midwife

Source: State law.

A 1995 academic study specifically reviewing the success of the perinatal program compared it to both the Obstetrical Access Project that preceded it and to Medi‑Cal members who had not participated in the perinatal program. The study found that when women in the perinatal program received at least the minimum number of visits recommended by the California Department of Health and Human Services in 1989, rates of low birthweight declined by 1.2 percentage points. To provide context, Medi‑Cal provided services that supported more than 165,000 births in 2021. A 1.2 percentage point difference in the rate of low birthweights could translate to nearly 2,000 additional babies born annually at a healthy weight. The study showed that when women did not receive at least the minimum number of recommended visits, rates of low birthweight did not improve significantly.

Until 2007 the perinatal program was solely within the purview of the California Department of Health Services. In that year, the Legislature renamed the Department of Health Services the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services) and split the former Department of Health Services’ duties and responsibilities between Health Care Services and the California Department of Public Health (Public Health). The Legislature designated Health Care Services as the sole agency responsible for administering Medi‑Cal and delegated the duties, powers, and responsibilities the Department of Health Services previously had over the perinatal program to Public Health.

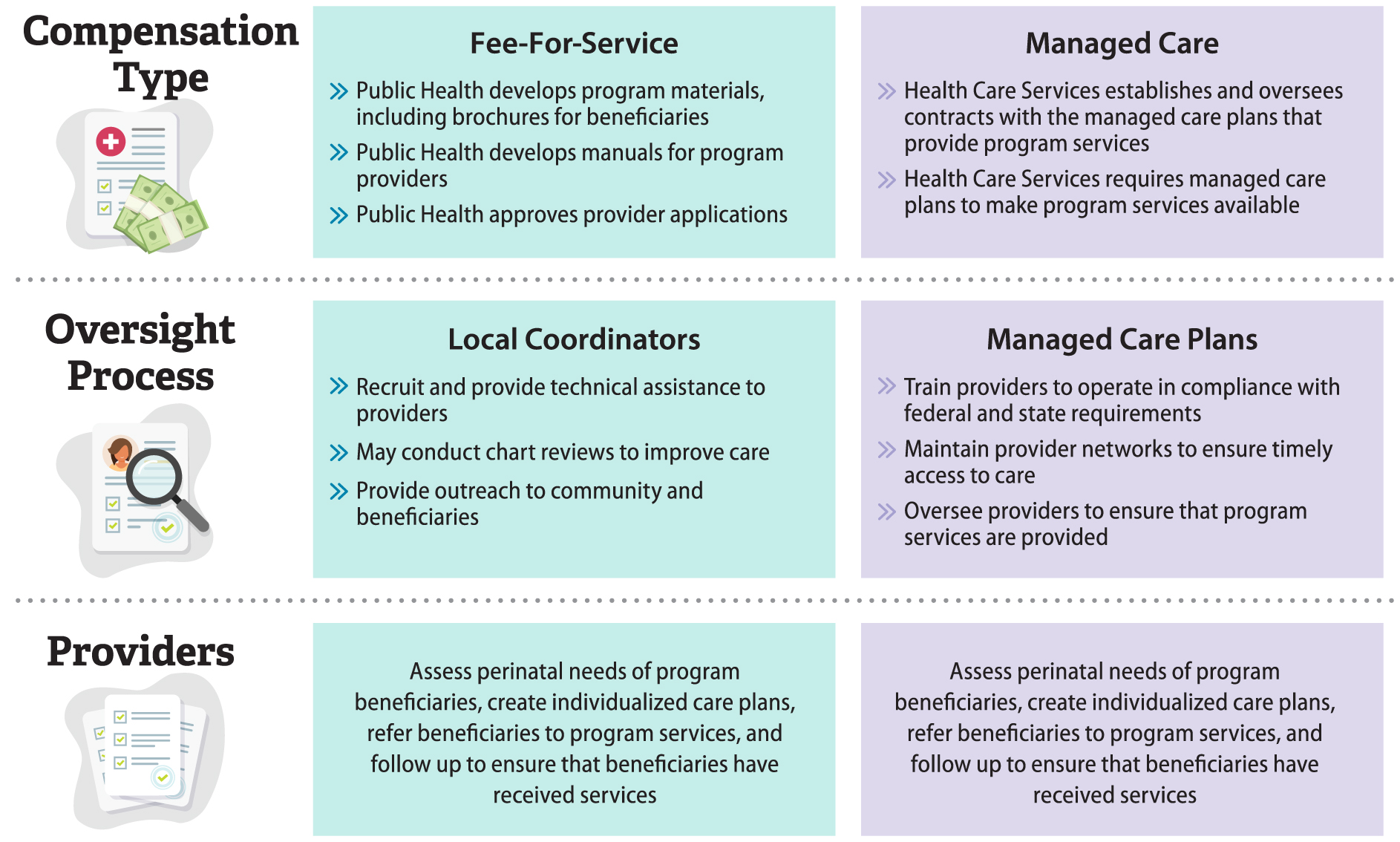

Two Models to Compensate Providers: Fee‑for‑Service and Managed Care

California provides Medi‑Cal benefits using two delivery systems: fee‑for‑service and managed care. Under the fee‑for‑service model, Health Care Services compensates providers per service delivered. For example, a perinatal program provider supplying a pregnant member with prenatal supplements or conducting a group perinatal education session would receive payment for those specific services. Public Health has interpreted its role in the perinatal program as focusing on fee‑for‑service providers. Although Public Health enrolls fee‑for‑service providers through local jurisdictions, it does not play a similar role for managed care providers.

Under the managed care model, managed care plans—such as Anthem Blue Cross or California Health and Wellness—rather than individual providers receive compensation through a monthly payment based on the number of people enrolled in a plan. This process is called capitation. When enrolling in managed care, Medi‑Cal members select a plan available in their geographical area. The plan in turn contracts with providers and practitioners to deliver health services to enrolled Medi‑Cal members. Providers contracted with managed care plans are required to submit patient encounter data to Health Care Services. Figure 2 summarizes the differences between state management and oversight of the fee‑for‑service and managed care models.

The Changing Landscape of Medi‑Cal and Perinatal Care

As part of its California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) initiative—a broad transformation intended to make Medi‑Cal more equitable, coordinated, and person-centered—Health Care Services has expanded the use of managed care plans and expects the vast majority of Medi‑Cal members to be enrolled in a managed care plan during 2024. According to Health Care Services, many of the remaining fee‑for‑service populations—about 1 percent of the current Medi‑Cal population—consist of new Medi‑Cal members with temporary eligibility, American Indian/Alaska Native Medi‑Cal members who live in non-COHS counties and choose to opt out of managed care enrollment, people with presumptive eligibility, and Medi‑Cal members who are foster youth, among others.4 Health Care Services’ assistant deputy director of health care delivery systems expects foster youth Medi‑Cal members to transition to managed care by 2025.

Figure 2

Public Health and Health Care Services Provide Perinatal Program Services Through Different Mechanisms

Source: State law, managed care contracts, department policies, and department guidance.

Figure 2 description:

Figure 2 is a chart comparing how Public Health and Health Care Services provide perinatal program services. The chart has three rows. The first row is titled Billing Type. In the Billing Type row, a blue box titled Fee-For-Service says that Public Health develops program materials including brochures for members, develops manuals for program providers, and approves provider applications. In the Billing Type row, a purple box titled Managed Care says that Health Care Services establishes and oversees contracts with the managed care plans that provide program services, and requires plans to make program services available. The second row is titled Oversight Process. In the Oversight Process row, a blue box titled Local Coordinators includes the activities: recruit and provide technical assistance to providers, may conduct chart reviews to improve care, and provide outreach to community and members. In the Oversight Process row, a purple box titled Managed Care Plans includes the activities: train providers to operate in compliance with federal and state requirements, maintain provider networks to ensure timely access to care, and oversee providers to ensure that program services are provided. The third row is titled Providers. In the Providers row, a blue box says that providers assess perinatal needs of program members, create individualized care plans, refer members to program services, and follow up to ensure that members have received services. In the Providers row, a purple box says that provider assess perinatal needs of program members, create individualized care plans, refer members to program services, and follow up to ensure that members have received services.

AUDIT RESULTS

The State Has Provided Limited Oversight and Has Not Exercised Its Authority to Make Program Improvements

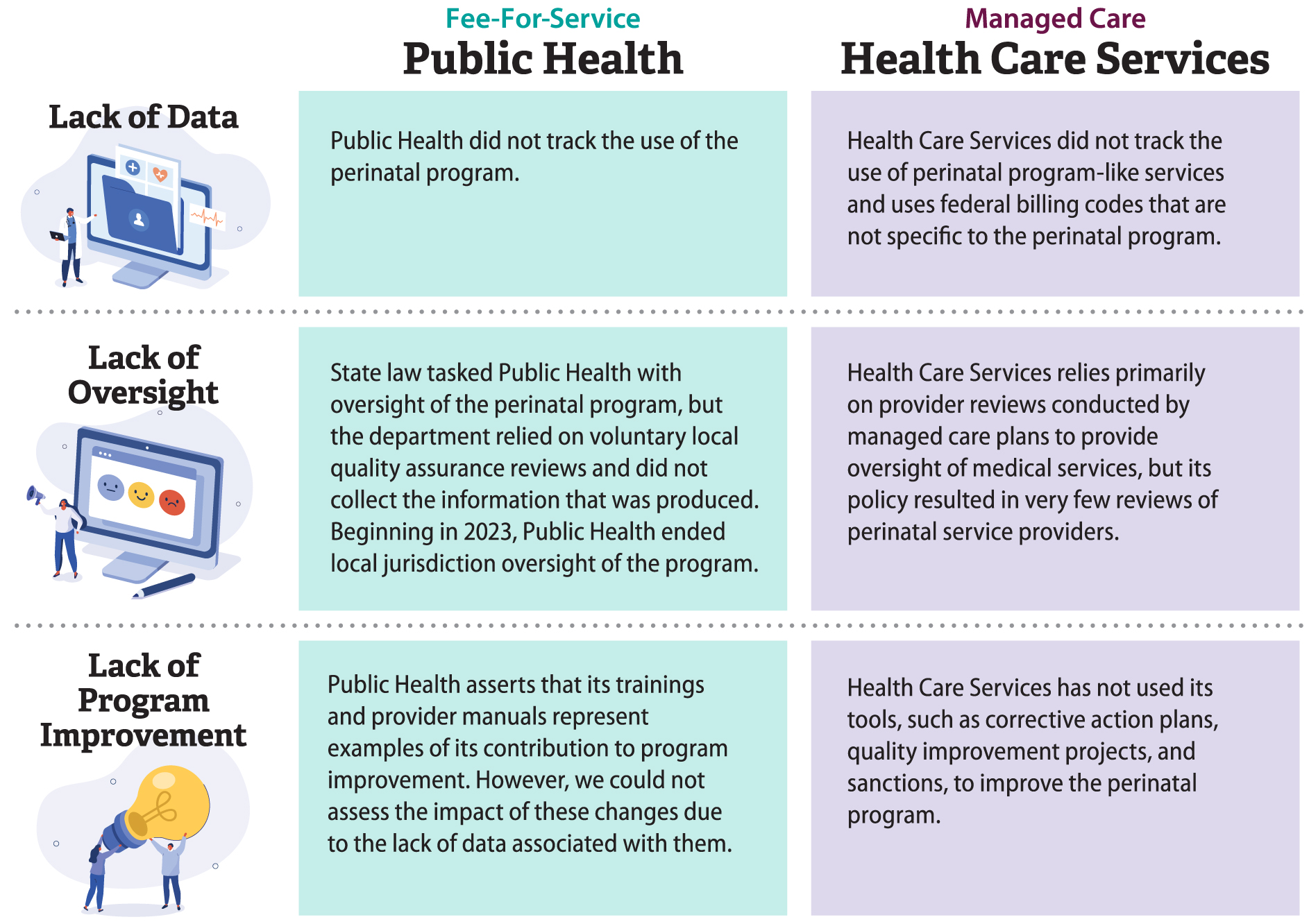

We found that Health Care Services and Public Health did not collect the data necessary for assessing whether Medi‑Cal members were using the perinatal program and that neither department conducted adequate oversight of the program or of the program’s providers. We also found that neither department has acted to significantly improve the perinatal program. We summarize our findings in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Health Care Services and Public Health Are Not Well Positioned to Oversee the Perinatal Program

Source: State law and findings contained in Report 2023-103.

Figure 3 description:

Figure 3 is a chart comparing how Public Health and Health Care Services lack data, oversight, and program improvement for the perinatal program. The chart has two columns. The first column is labeled Public Health, under a Fee-For-Service model. The second column is labeled Health Care Services, under a Managed Care model. The chart has three rows. The first row is titled Lack of Data. In the Lack of Data row under the Public Health column, a blue box says that Public Health did not track the use of the perinatal program. In the Lack of Data row under the Managed Care column, a purple box says that Health Care Services did not track the use of perinatal program-like services, and uses federally mandated billing codes that are not equivalent to the perinatal program. The second row is titled Lack of Oversight. In the Lack of Oversight row under the Public Health column, a blue box says that state law tasked Public Health with oversight of the perinatal program, but the department relied on voluntary local quality assurance reviews and did not collect the information that was produced, and that beginning in 2023, Public Health ended local jurisdiction oversight of the program. In the Lack of Oversight row under the Health Care Services column, a purple box says that Health Care Services relies primarily on provider reviews conducted by managed care plans to provide oversight of medical services, but its policy resulted in very few reviews of perinatal service providers. The third row is titled Lack of Program Improvement. In the Lack of Program Improvement row under the Public Health column, a blue box says that Public Health asserts that its trainings and provider materials represented examples of its contribution to program improvement, and says that, however, we could not assess the impact of these changes due to the lack of data. In the Lack of Program Improvement row under the Health Care Services column, a purple box says that Health Care Services has not used its tools, such as corrective action plans, quality improvement projects, and sanctions, to improve the perinatal program.

The State Lacks the Data Necessary to Evaluate Usage of the Perinatal Program

We attempted to calculate usage rates for perinatal program services, but there are significant limitations in the data. Specifically, managed care plans, which covered roughly 91 percent of Medi‑Cal members as of July 2023, track the services they provide using procedure codes that are not specific to the perinatal program. Although the perinatal program has specific procedure codes that exist for fee‑for‑service providers, managed care plans are not required to use these codes. Health Care Services identified a list of 55 procedure codes that managed care plans might use when providing services that are comparable to services provided in the perinatal program. However, 39 of the 55 procedure codes identified are not exclusive to pregnancy-related services. For example, Health Care Services identified a generic procedure code that it determined to be comparable to the perinatal program’s initial office visits; however, managed care providers may also use that code for general clinic visits unrelated to pregnancy. Because these generic codes are not exclusive to perinatal program-specific services, Health Care Services cannot use them to differentiate between a member’s use of these services and other health services. Thus, it is not possible to calculate the perinatal program’s utilization rate for managed care plans since these generic codes inflate the results. According to Health Care Services, the federal government is phasing out the use of state-specific codes, and it limits the number of codes a provider may use when reporting on an appointment with a Medi‑Cal member. Therefore, additional codes for tracking perinatal services, or requiring managed care providers to use the same codes that some fee‑for‑service providers use, are not likely solutions to tracking usage related to managed care providers.

Although we were able to determine the perinatal program’s utilization rates for fee‑for‑service Medi‑Cal members, as Table 1 shows, this information is not sufficient on its own to determine the effectiveness of the program. The number of fee‑for‑service Medi‑Cal members has diminished, from roughly 19 percent of eligible Medi‑Cal members in 2018 to about 14 percent at the end of 2022. In addition, according to Health Care Services reports, the percentage of fee‑for‑service members decreased even further in July 2023—comprising only 9 percent of eligible Medi‑Cal members. Because managed care plans do not use procedure codes specific to the perinatal program, we cannot use these data to compare the receipt of these specific services between fee‑for‑service and managed care Medi‑Cal members. However, we note that utilization rates for the fee-for-service component of the program have improved as Table 1 demonstrates.

Although the figures in Table 1 represent a small and shrinking population of Medi‑Cal members, they demonstrate a utilization rate within that population that has room for further improvement. In 2022 a little more than half of pregnant Medi‑Cal members in fee‑for‑service plans received perinatal program services during pregnancy. While these services are voluntary, all pregnant Medi‑Cal members are eligible for them; thus, it is possible that some who needed the services did not get them. Further, less than 16 percent received perinatal services within 60 days after birth. Because the providers serving this population have opted into the perinatal program, and thus should be more knowledgeable about and motivated to refer patients for perinatal services, we expected to see higher usage. According to Health Care Services, there is no established level of expected usage, and Public Health noted that Medi‑Cal members are not required to use these services and may reject them. Regardless, the numbers suggest the possibility that some who needed the services may not have received them.

Because Medi‑Cal billing data cannot give us a reasonable estimate of program usage, another method for collecting program data could help assess utilization. Specifically, state law requires that Public Health monitor and oversee the perinatal program using a perinatal data form. The law requiring this form was established in 1984 when the Department of Health Services was responsible for the program. However, Public Health’s perinatal program manager told us that data collection specific to the perinatal program is done at the local level, and the forms and templates Public Health has created are for use locally. Public Health does not collect data itself to produce a usage report or an evaluation report of the perinatal program. In addition, as we describe later in the report, such local reviews are completed inconsistently, and Public Health does not collect and analyze the results of the local reviews. We examined forms in use by local health care coordinators, and specifically the form used in medical record reviews, and based in part on that form, we provide an example of what a comprehensive perinatal data collection form might look like in Appendix A.

Given that Medi‑Cal billing data are not useful in assessing program usage, program‑specific data collection and analysis by Public Health would have been a useful tool for determining usage and ensuring that providers rendered quality perinatal care to Medi‑Cal members. In the absence of useful data, other methods of oversight become essential to ensure that Medi‑Cal members are receiving program‑related services. However, as the remainder of the report discusses, neither Public Health’s oversight nor Health Care Services’ oversight of the perinatal program or its services are sufficient in their current state.

Managed Care Plans and the Department of Health Care Services Conduct Little Review of the Perinatal Program

Although Health Care Services has a number of tools for evaluating managed care plans’ delivery of services, its evaluation of perinatal services specifically is minimal. Managed care plans’ contracts with the department require them to offer perinatal program services or services that are comparable to the perinatal program. As part of its overall oversight of Medi‑Cal managed care, Health Care Services requires managed care plans to conduct reviews of each primary care provider (provider reviews) at least once every three years. These reviews are sometimes called triennial plan reviews. Health Care Services has required provider reviews to include the components of the perinatal program since at least 2002, when it standardized the review process. Since that time, managed care plans have been required to use a standardized provider review tool to evaluate patients’ medical records for legal proof that the patients received quality, timely, and appropriate medical care. The Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program section (CPSP section) of that tool contains an evaluation of perinatal program services offered, including trimester and postpartum assessments, individualized care plans, and follow-up services. Providers receiving a score below 80 percent on one or more sections of the provider review must submit a corrective action plan to the managed care plan, and the managed care plans are responsible for ensuring that providers have implemented a process to make the corrections. Health Care Services requires managed care plans to submit the data from their provider reviews and to report on the progress of their providers’ corrective actions twice yearly.

However, Health Care Services’ existing policies and its contractual agreements with managed care plans limit reviews of perinatal services. Because Health Care Services’ provider reviews are limited to primary care providers, perinatal service providers who do not serve as primary care providers are omitted from these reviews. For example, state law and Health Care Services allow OB-GYNs—who may frequently provide or supervise the provision of perinatal services—to serve as primary care providers if that OB-GYN meets eligibility criteria for providing primary care. Therefore, OB-GYNs and other perinatal service providers who offer perinatal services, such as assessments and referrals, but who are not designated primary care providers, do not receive a provider review. As of January 2024, only 520 of the 3,140 OB-GYNs in the managed care system—or 17 percent—were designated as primary care providers.

Additionally, although Health Care Services requires that reviewers use the CPSP section to evaluate primary care providers who provide perinatal services, this does not always occur. For example, Health Care Services notes that primary care providers who offer pregnancy-related services as only a part of their practice may not maintain records related to these services at the site being reviewed. Therefore, both the perinatal services providers whose health care delivery is not subject to review and the providers whose reviews do not include an assessment of the perinatal program services they provide, present a missed opportunity for Health Care Services and managed care plans to evaluate perinatal program services.

As a result of these policies and practices, managed care plans rarely use the CPSP section in their provider reviews. In fact, statewide data on managed care plans’ provider reviews indicate that only 45 of about 2,600 provider reviews conducted in 2022 examined the provision of perinatal program services, and these 45 reviews examined perinatal services in only 18 of the State’s 58 counties. This means that Health Care Services cannot demonstrate that managed care plans are offering perinatal program services to their Medi‑Cal members as required, and it cannot draw conclusions or make recommendations that would improve providers’ services.

Health Care Services also performs its own review of providers and conducts spot checks of the data that managed care plans submit on the plans’ reviews; however, the scope of both of these activities is limited. Health Care Services’ provider reviews follow the same procedures and use the same tools that the managed care plans use. Department procedures direct staff to select a county and managed care plan at least once a month for a review of providers; however, Health Care Services only conducted 18 such reviews from 2018 through 2022. According to Health Care Services, travel was suspended in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic, thus preventing reviews. Nevertheless, for 2018, 2019, and 2022, we expected 36 reviews, but Health Care Services conducted half that number.

Like the managed care plans, Health Care Services rarely evaluates providers using the CPSP section of the review tool. Of the 1,256 individual medical records that Health Care Services evaluated during its provider reviews, only 19—about 2 percent—included perinatal services. Health Care Services asserts that its provider reviews ensure that the plans are holding their providers accountable to Medi‑Cal standards. However, Health Care Services does not use the results of its provider reviews to make recommendations to the managed care plans. Rather, it requires the managed care plans to conduct additional follow-up with the individual providers the department reviewed. Therefore, Health Care Services’ provider reviews do not offer suggestions for systemic improvement to managed care plans’ provision of Medi‑Cal services.

Further, Health Care Services claims it conducts spot checks of the managed care plan reviews, but these spot checks are also limited. Health Care Services’ procedures direct department staff to review the managed care plans’ provider review data for trends. However, the chief of Health Care Services’ Managed Care Quality and Monitoring division explained that compiling and comparing these data in a meaningful way is difficult and time-consuming under its current system; thus, the department’s spot checks are limited. As a result, the department is currently unable to draw conclusions about the perinatal program’s performance or identify areas where providers are deficient and may need additional training or support.

Health Care Services’ director of managed care quality and monitoring acknowledged that her division’s methods of providing oversight are not sufficient by themselves to monitor the perinatal program. She explained that Health Care Services is in the final stages of implementing a new data system—the Managed Care Site Review Portal—to collect results of provider reviews from managed care plans, in part, because it is concerned with the lack of efficiency in many of the department’s oversight processes. Health Care Services anticipated that it would have enough data for analysis in late January 2024, when managed care plans will complete uploading their provider review data from the second half of 2023 to the new data system. Health Care Services reported that the new data system will allow it to identify trends at a plan or regional level, sort and track patient demographics to determine potential disparities in care, and more easily monitor how the managed care plans conduct their provider reviews. Although this will be beneficial for Medi‑Cal managed care oversight as a whole, the new data system will be of limited use as an oversight tool for the perinatal program if Health Care Services does not also update its policies to ensure that the managed care plans review more providers who provide perinatal services, such as OB-GYNs who might not be primary care providers.

Public Health Does Not Provide Oversight of the Perinatal Program, and Local Oversight Has Historically Been Limited

Local reviews of fee‑for‑service providers in the perinatal program has been limited. Although state law tasked Public Health in 2007 with the overall oversight and monitoring of the perinatal program, the department has relied on voluntary local oversight, and as we note in the Introduction, Public Health has interpreted its role as focused on fee‑for‑service providers. Public Health has informed local health care jurisdictions (jurisdictions) that local coordinators may conduct quality assurance visits (chart reviews) to monitor the fee‑for‑service component of the perinatal program. However, Public Health neither requires these visits nor collects the information they may produce. We surveyed the 61 local health jurisdictions in California to determine the extent of local monitoring. Of the 60 jurisdictions that responded, 38 reported conducting chart reviews while 22 jurisdictions—or 37 percent of respondents—reported that they did not conduct chart reviews from 2018 through 2022. Thirty two jurisdictions cited the pandemic as a reason for a reduced number of reviews or for not conducting any reviews. Of the 22 jurisdictions that did not conduct any reviews, 17 reported that they did not have any fee‑for‑service providers during those years. However, we could not verify this assertion because Public Health does not maintain a complete list of active providers due to variations in reporting requirements.5 The remaining five jurisdictions reported that they did not conduct chart reviews primarily due to staffing limitations and the effects of the pandemic. In those jurisdictions that conducted chart reviews, such as Santa Clara and Alameda, the number of chart reviews declined from an average of 13 quality assurance reviews per jurisdiction in 2018 to an average of only five in 2022. Overall, jurisdictions reported conducting 730 chart reviews in 2018, which decreased to a total of 290 in 2022. According to Public Health, this reduction may also have been due to the pandemic. Public Health asserts that its role is approving providers, not monitoring them for compliance, an assertion we find to be at odds with its oversight and monitoring responsibilities under state law.

When they did occur, local coordinators’ chart reviews assessed key elements of the perinatal program. Local coordinators may conduct reviews and give technical assistance to providers during site visits where they review medical charts as well as administrative reviews and they may conduct interviews with provider staff. For example, chart reviews assessed whether providers offered expected services, created individual care plans to mitigate identified risks, and provided appropriate referrals; they also noted the extent to which follow-up assessments occurred. Two jurisdictions we reviewed, Sonoma and Fresno, conducted a total of 11 chart reviews between 2017 and 2023.6 We noted that completed chart reviews documented whether a provider had delivered specific perinatal program services, such as assessments and referrals. Those chart reviews also identified deficiencies, such as providers’ lower levels of compliance in completing individualized care plans and a lack of follow-up on the risks and issues identified in the care plans. If Public Health had made chart reviews mandatory and collected the resulting information, those reviews could have served as an important source for statewide information on the program, such as whether providers are offering services and where to target additional training.

Public Health explained that because it is aware of limited resources at the local level, it did not require that local health jurisdictions conduct chart reviews, nor did it collect completed reviews in order to conduct its own analysis. Public Health noted that it lacked sufficient resources to analyze the chart reviews even if it had collected them; however, it had not sought additional funding or staffing. Instead, Public Health has relied on anecdotal information it collected during its meetings with local coordinators. Although the chart reviews themselves were focused on quality assurance related to providers, because Public Health neither collected nor analyzed the resulting data, it lacked an important data source.

In May 2023, Public Health decreased oversight of fee‑for‑service providers. It informed local health jurisdictions that Health Care Services planned for 99 percent of Medi‑Cal members to be enrolled in managed care programs by January 2024, which meant that the number of fee‑for‑service providers enrolling in the perinatal program was expected to further decline. Public Health said it would therefore take over the local coordinators’ responsibilities, such as approving provider applications to the program, offering technical support, and reviewing protocols that providers are required to submit that describe how they will provide care. Public Health said that local health jurisdictions will continue to receive funding for local coordinators, but those coordinators’ duties will shift away from monitoring the delivery of services. Local coordinators will continue to perform outreach to the public and work with managed care plans and with other maternal and perinatal care providers to ensure accessibility and equity.

Rather than conduct chart reviews, Public Health plans to transition to an annual provider survey, which we note will be an insufficient monitoring tool because it lacks independent verification. This annual survey will require fee‑for‑service providers to self-certify that they have complied with perinatal program procedures and state regulations. However, Public Health does not currently plan to independently verify any of the responses it receives. This means that although there will be fewer fee‑for‑service providers to oversee, oversight of those providers will be further reduced. When we asked Public Health whether a survey of provider‑supplied responses can fulfill an oversight responsibility, the director of perinatal programs acknowledged the limitation of the lack of independent verification, but she asserted that as the department learns more about the perinatal program from the new oversight process, it plans to refine the survey. However, without some form of independent verification of the results of the survey, Public Health cannot be confident that providers are complying with the program’s rules or offering care that would improve perinatal health outcomes.

Health Care Services Has Tools, Such as Audits, to Monitor Perinatal Services, But It Does Not Focus on the Program Specifically

Health Care Services has not used its enforcement tools, such as corrective action plans resulting from regular medical audits, to prompt improvements specific to the perinatal program. State law authorizes Health Care Services to impose a plan of correction for findings of noncompliance or for other good cause on any entity under contract with it to deliver health services. Health Care Services conducts annual medical audits of managed care plans to evaluate their compliance with their contracts with the department and with applicable laws and regulations, and Health Care Services may require managed care plans to develop corrective action plans to address audit findings. Health Care Services says it conducts a risk assessment in preparation for each audit, but it does not have specific audit steps and procedures to examine the perinatal program.

Health Care Services’ medical audits from 2018 through 2022, which we reviewed in their entirety, did not mention the perinatal program specifically. However, 32 of the 90 audit reports mentioned perinatal care, pregnancy care, or both, and 14 had findings related to such care. For example, one audit found that the managed care plan did not guarantee timely prenatal appointments and recommended that the plan develop and implement policies to ensure that initial prenatal appointments are monitored for timely access. Four audits found that plans had incorrectly denied claims for family planning services and recommended corrections. While related to perinatal services broadly, the findings in these reports did not relate to the extended services offered through the perinatal program. Although such services may come up in an audit because the services are part of the universe of Medi‑Cal-covered health care, without specifically focusing on services offered through the perinatal program, Health Care Services is not ensuring that plans and providers are offering those services to members.

Further, the corrective action plans resulting from these audits are useful for identifying areas of improvement and thus could help improve perinatal services. For example, in a 2019 medical audit, Health Care Services found that a managed care plan lacked procedures to follow up on missed appointments, and Health Care Services required the managed care plan to respond to the identified problem. The managed care plan reported that it updated its procedures to include follow-up on missed appointments and implemented a monitoring system to ensure that its providers followed the new procedures.

Managed care plans’ mandatory performance and quality improvement projects (improvement projects) can be an effective tool in encouraging managed care plans to focus their quality improvement work on a particular topic or measure. Federal regulations require managed care plans to conduct improvement projects and report their results to Health Care Services at least once per year. Health Care Services directs managed care plans to choose the topics of one of their improvement projects in one of Health Care Services’ priority areas, and it encourages the plans to choose the topic of the other project to address a health disparity in which the managed care plan has a demonstrated need for improvement. Managed care plans set goals and define measures to improve care within their selected topics, identify potential interventions, test and evaluate these interventions, and interpret the results.

Although not specifically focused on the perinatal program, maternal health has been one of Health Care Services’ priority areas since at least 2015. From 2018 to 2022, five of the State’s 24 managed care plans active during that time selected a component of perinatal care—postpartum care—as one of their improvement project topics. All five of these managed care plans developed interventions to address low rates of postpartum care visits and tested the interventions to determine whether they were effective. For example, one managed care plan found that by providing additional education on the importance of postpartum care and assisting Medi‑Cal members with scheduling appointments, it successfully increased the rate of postpartum visits. Another managed care plan added a color-coded alert to its appointment scheduling system in order to assist staff with scheduling timely postpartum visits, and its rate of postpartum visits increased. These improvement projects can be an effective tool in improving managed care plans’ perinatal care.

Further, Health Care Services plans to increase communication among health plans. Health Care Services reports that it conducts follow-up quality improvement activities with managed care plans that continue to underperform at the end of an improvement project. Health Care Services has also drafted a policy, which, if implemented, will require managed care plans to participate in regional collaborative calls to improve the quality of care by sharing best practices and by increasing collaboration. Such collaboration, when focused on perinatal program services, could lead to improvements in care through sharing best practices arising from the corrective action plans or other sources. This in turn could increase the use of perinatal services and lead to more positive health outcomes.

Finally, Health Care Services has not identified concerns related to perinatal program services that required sanctions. State law authorizes Health Care Services to impose administrative and financial sanctions on managed care plans that violate laws related to Medi‑Cal or that violate the terms of their contracts with the department. Health Care Services may impose sanctions on a managed care plan together with or in lieu of a corrective action plan or when the managed care plan fails to complete a corrective action plan. For example, in 2018, the department imposed monetary sanctions on two managed care plans for failing to meet minimum performance levels set forth in corrective action plans. Health Care Services reports that sanctions can be an effective method of motivating improved performance in managed care plans that significantly underperform. From 2018 through 2022, Health Care Services issued a total of 21 sanctions to managed care plans. While none of the sanctions related to the perinatal program or comparable services, this is a tool Health Care Services can use, if necessary, to improve perinatal care.

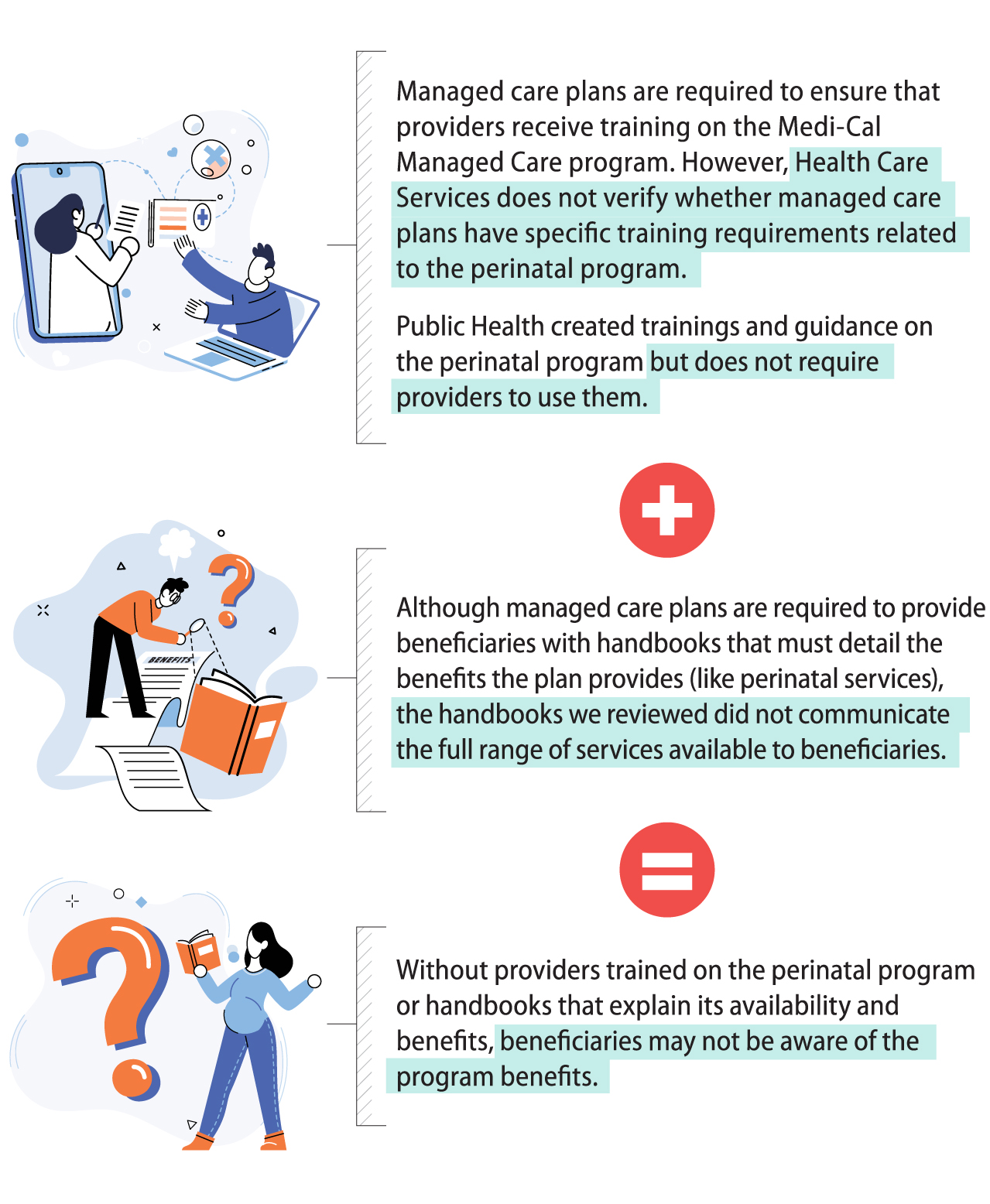

The State Does Not Sufficiently Communicate the Availability of the Perinatal Program to Providers or Members

We found that neither Health Care Services nor Public Health adequately trained providers on the perinatal program or provided Medi‑Cal members with adequate information about the importance and availability of the program’s services, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4

Health Care Services and Public Health Have Not Sufficiently Communicated Information on the Perinatal Program to Providers or Medi‑Cal Members

Source: State law and regulation; Public Health’s documents, website, and interviews with its staff; interviews with Health Care Services’ staff, and managed care plan handbooks.

Figure 4 description:

Figure 4 is a graphic demonstrating that the combination of a lack of provider training on program requirements and a lack of description of perinatal program services in member handbooks means that members may not be aware of the perinatal program benefits. At the top is an image of a telehealth visit between a doctor with long dark hair in a white lab coat and a patient with short dark hair in a blue shirt. The attached description reads: ‘Managed care plans are required to ensure their providers receive training on the Medi-Cal Managed Care Program. However, Health Care Services does not verify whether managed care plans have specific training requirements related to the perinatal program. Public Health created trainings and guidance on the perinatal program but does not require providers to use these.’ Beneath this text is a red circle containing a white plus sign. Beneath the red circle containing the white plus sign is another image and attached description. The image depicts a person with short dark curly hair in an orange shirt reading through written materials with a question mark above their head. The attached description reads: ‘Although managed care plans are required to provide beneficiaries with handbooks that must detail the benefits the plan provides (like perinatal services) the handbooks we reviewed did not communicate the full range of services available to members.’ Beneath this text is a red circle containing a white equals sign. Beneath the red circle containing the white equals sign is another image and attached description. The image depicts a pregnant person with long dark hair and a light blue shirt reading through written materials with a question mark beside them. The attached description reads: ‘Without provider trained on the perinatal program or handbooks that explain its availability and benefits, members may not be aware of the program benefits.

Neither Health Care Services nor Public Health Ensured That Managed Care Plans or Providers Were Sufficiently Educated on the Perinatal Program

Health Care Services’ Contract Oversight Division was unable to provide documentation demonstrating that the managed care plans conducted provider education on the perinatal program. The division explained that the contracts with managed care plans do not specifically contain requirements for provider education on the perinatal program, and the division does not verify whether plans have perinatal program‑specific education and training requirements. Although the contracts require the managed care plans to ensure that their providers receive training, according to Health Care Services, individual units within the department that oversee certain programs make decisions regarding training requirements in those areas. Nevertheless the State’s contracts with managed care plans require training as it relates to Medi‑Cal Managed Care services, policies, and procedures. If providers do not receive training on the services available through the perinatal program, it is possible that they will not know to refer patients for perinatal services for which they qualify.

Further, Public Health created manuals and training sessions to inform providers of perinatal program requirements, but the department does not require their use. Public Health’s provider training materials include information on how to implement the perinatal program, including benefits providers should offer and which providers may deliver services. Public Health also provides lists of questions that providers may ask Medi‑Cal members and of suggested actions based on potential responses. However, Public Health does not require that providers participate in this training. Although Public Health maintains records of individuals who attend live trainings or who have accessed training online, the materials are also now publicly available online, and Public Health cannot be sure that providers who do not attend the training have obtained information on their own. Public Health explained that it does not require provider training because its current regulations do not require training specific to the perinatal program. However, as Public Health is authorized to adopt and enforce regulations for the execution of its duties, it could have taken action to adjust its regulations to support more positive maternal health outcomes by ensuring that providers are informed of benefits and requirements.

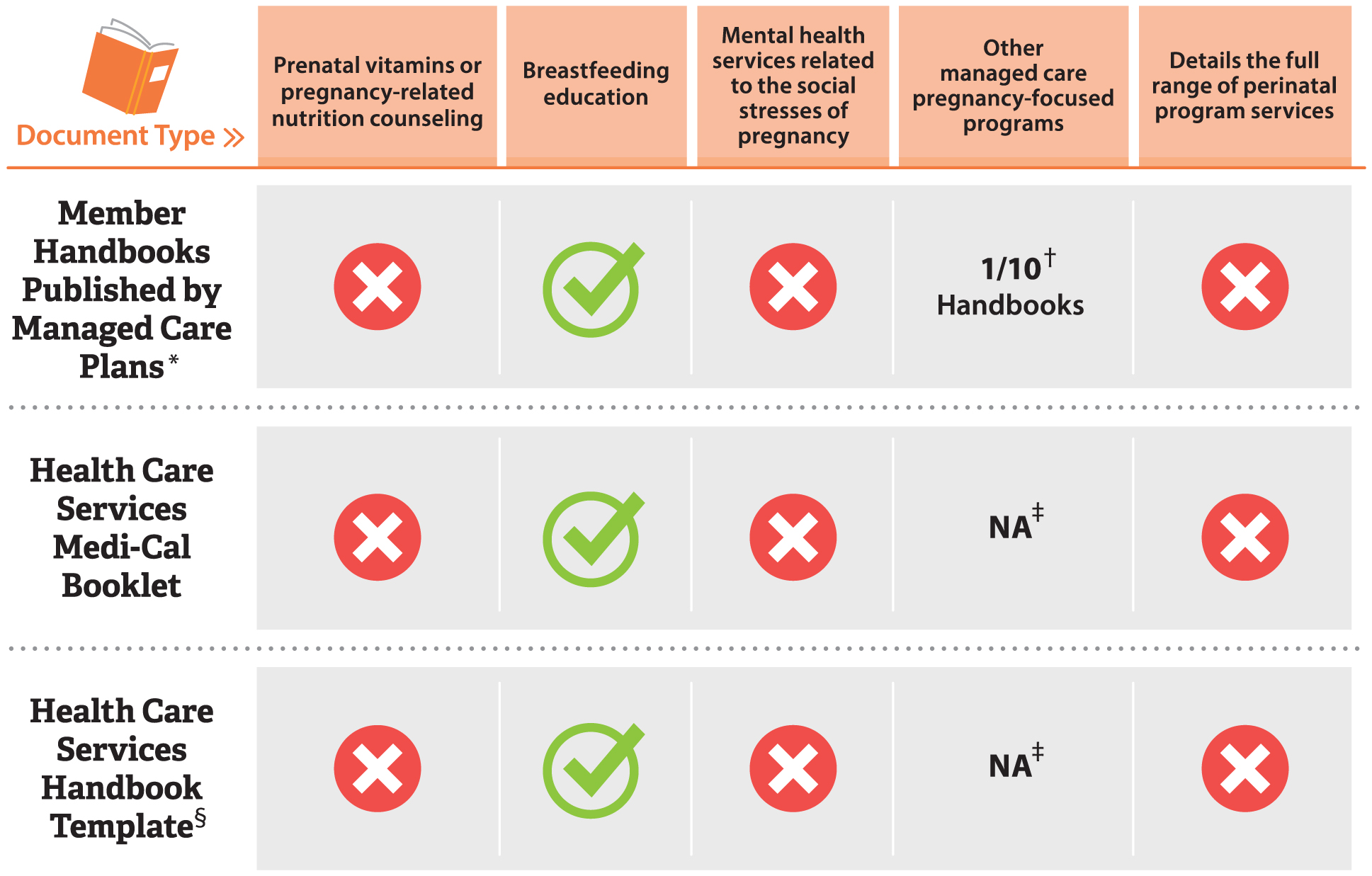

Medi‑Cal Member Handbooks Do Not Inform Members of Perinatal Program Benefits as Required

Health Care Services and the managed care plans give Medi‑Cal members member handbooks, but the handbooks do not fully describe perinatal services. Federal regulations require managed care plans to provide their members with a handbook, which must sufficiently describe the benefits that the plan provides so that members can understand what they are entitled to, and it must offer instructions on how to access these benefits. Because the perinatal program is one such benefit, managed care plans should include information on the program in their handbooks. We reviewed the 2018 and 2023 handbooks from the five managed care plans that provide services in our selected jurisdictions (10 handbooks total) to determine whether the handbooks describe the perinatal program and its services. We summarize our findings in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Health Care Services Does Not Ensure That Potential Beneficiaries of the Perinatal Program Are Informed of Its Services

Source: Managed care plan member handbooks, templates, and My Medi‑Cal booklet.

* We reviewed handbooks from the five managed care plans providing perinatal services in our selected local health jurisdictions—Fresno, Imperial, Plumas, and Sonoma—from 2018 and 2023.

† One handbook from California Health and Wellness in 2018 described the Smart Start for Baby program but did not describe the full range of program services.

‡ The Health Care Services Medi‑Cal Booklet is a document for all Medi-Cal members regardless of plan, and we would not expect it to have information on specific programs in managed care plans. The Health Care Services Handbook Template is a managed care plan facing document.

§ We reviewed the noted documentation produced by Health Care Services in 2018 and 2023.

Figure 5 description:

Figure 5 is a chart showing the inclusion or exclusion of information about various pregnancy-related services in three different types of documents. The chart has three rows, with each row representing a type of document. The first row is titled Member Handbooks Published by Managed Care Plans. The second row is titled Health Care Services Medi-Cal Booklet. The third row is titled Health Care Services Handbook Template. The chart has five columns, with each column representing information on benefits and services. The first column is labeled ‘Prenatal vitamins or pregnancy-related nutrition counseling,’ and three red circles, each containing a white X, indicate that this information is not included in any of the three types of documents. The second column is labeled ‘Breastfeeding education,’ and three green circles, each containing a green checkmark, indicate that this information is included in all three of the types of documents. The third column is labeled ‘Mental Health services related to the social stresses of pregnancy,’ and three red circles, each containing a white X, indicate that this information is not included in any of the three types of documents. The fourth column is labeled ‘Other Managed Care pregnancy-focused programs,’ and two of the rows in this column are labeled ‘N/A,’ indicating that this information is not applicable within the Health Care Services Medi-Cal Booklet or the Health Care Services Handbook Template. The first row contains a note indicating that one of the ten handbooks we reviewed contained information about another managed care pregnancy-focused program. The fifth column is labeled ‘Details the full range of perinatal program services,’ and three red circles, each containing a white X, indicate that this information is not included in any of the three types of documents.

The managed care plan handbooks we reviewed do not describe the enhanced services specific to the perinatal program, although they often describe services in general. For example, state law requires that a perinatal program member receive a complete psychosocial assessment that includes a review of the member’s personal adjustment to pregnancy, the patient’s goals in the pregnancy, and their general emotional status. However, all five of the handbooks we reviewed from 2018 only describe the availability of general mental health care, a service that is available to all Medi‑Cal members regardless of pregnancy. The five 2023 handbooks we reviewed do provide a general reference to maternal mental health but do not offer practical details and specific services. Because of this lack of information, a pregnant or postpartum member may not understand the availability of treatment for mental health issues specific to pregnancy. Likewise, the handbooks do not sufficiently describe other services, such as access to pregnancy-related nutrition counseling or health education. As Figure 5 shows, we generally expected to see benefits such as those described in the Introduction in Figure 1. Specifically, we expected to see benefits such as coverage for prenatal vitamins or services related to the social stress of pregnancy, but the handbooks do not describe these specific examples. Without this level of detail, Medi‑Cal members may not know that they have access to these services.

Health Care Services provides templates for managed care plans to use when developing their own member handbooks, but the templates contain limited information about perinatal program services. We found that the member handbooks we reviewed are substantially similar to the templates that Health Care Services provides to plans. Plans may make changes to the template in developing their handbooks, such as one handbook that described a health coaching benefit to help manage conditions such as asthma or back pain that is not described in the template. However, Health Care Services’ Contract Oversight Division told us that it reviews and approves all handbooks; thus, it is likely that plan handbooks will closely follow the provided templates.

Health Care Services’ templates do not describe perinatal benefits in a way that tells Medi‑Cal members that they are eligible for enhanced psychosocial, nutrition, or health education assessments. For example, both the templates and handbooks describe some maternity care services, such as delivery and postpartum care, but they do not describe the perinatal program or its enhanced care, such as perinatal health education or psychosocial care. Health Care Services acknowledges that maternity care services are generally described in the handbook, and those descriptions could include perinatal program services [emphasis ours]. However, without more specific information, Medi‑Cal members who are or who may become pregnant may not be aware of the perinatal program’s enhanced services and may not know to ask their health care providers.

Because the Future of the Perinatal Program Lies With Managed Care, Health Care Services Should Take Responsibility for the Program

Nearly all Medi‑Cal members will be enrolled in managed care plans during 2024, reducing the role that Public Health will play in future oversight of the perinatal program. As part of its CalAIM initiative—a broad transformation intended to make Medi‑Cal more equitable, coordinated, and person-centered—Health Care Services is expanding the use of managed care plans, and the department expects 99 percent of Medi‑Cal members to be enrolled in a managed care plan in 2024. Because of the transition away from large-scale use of the fee‑for‑service model in favor of managed care, Public Health has taken over the responsibilities local coordinators previously completed under fee‑for‑service. For example, Public Health, rather than the local coordinators, began offering technical assistance to fee‑for‑service program providers in July 2023. With such a small percentage of Medi‑Cal members in the fee‑for‑service program, Public Health’s role in overseeing the perinatal program will continue to diminish, and Health Care Services’ monitoring of its managed care plans will have increased importance.

Many of Health Care Services’ CalAIM initiatives—an ongoing process without a planned end date—if integrated into the perinatal program, could help managed care plans achieve program goals. For example, Health Care Services asserts that Medi‑Cal members with unmet social needs—such as housing and food insecurity—are at higher risk of poor health outcomes and may require higher-cost services. Accordingly, a component of CalAIM will include encouragement by Health Care Services for managed care plans to offer a variety of medically appropriate community supports to help Medi‑Cal members meet their health-related social needs, recover from illness, and avoid costlier health care in the future. For example, researchers identified living arrangements as a factor in health outcomes for mothers and infants in the original 1982 pilot project that prompted the creation of the perinatal program. ACOG also recommends that providers use referrals to social services to improve patients’ abilities to meet their basic health needs, including access to stable housing. Health Care Services suggests that managed care plans offer housing transition navigation services as a community support, which would help Medi‑Cal members with finding, applying for, and securing affordable housing. If managed care plans were to offer this community support, perinatal program providers could refer pregnant and post-partum Medi‑Cal members at risk of experiencing homelessness to these community support providers as a follow-up service. By successfully implementing CalAIM to include these community supports as currently planned, Health Care Services could increase the chances of positive perinatal outcomes. However, the success of this effort remains to be determined, and CalAIM will likely not be fully assessable for several years as it is a recent and ongoing initiative.

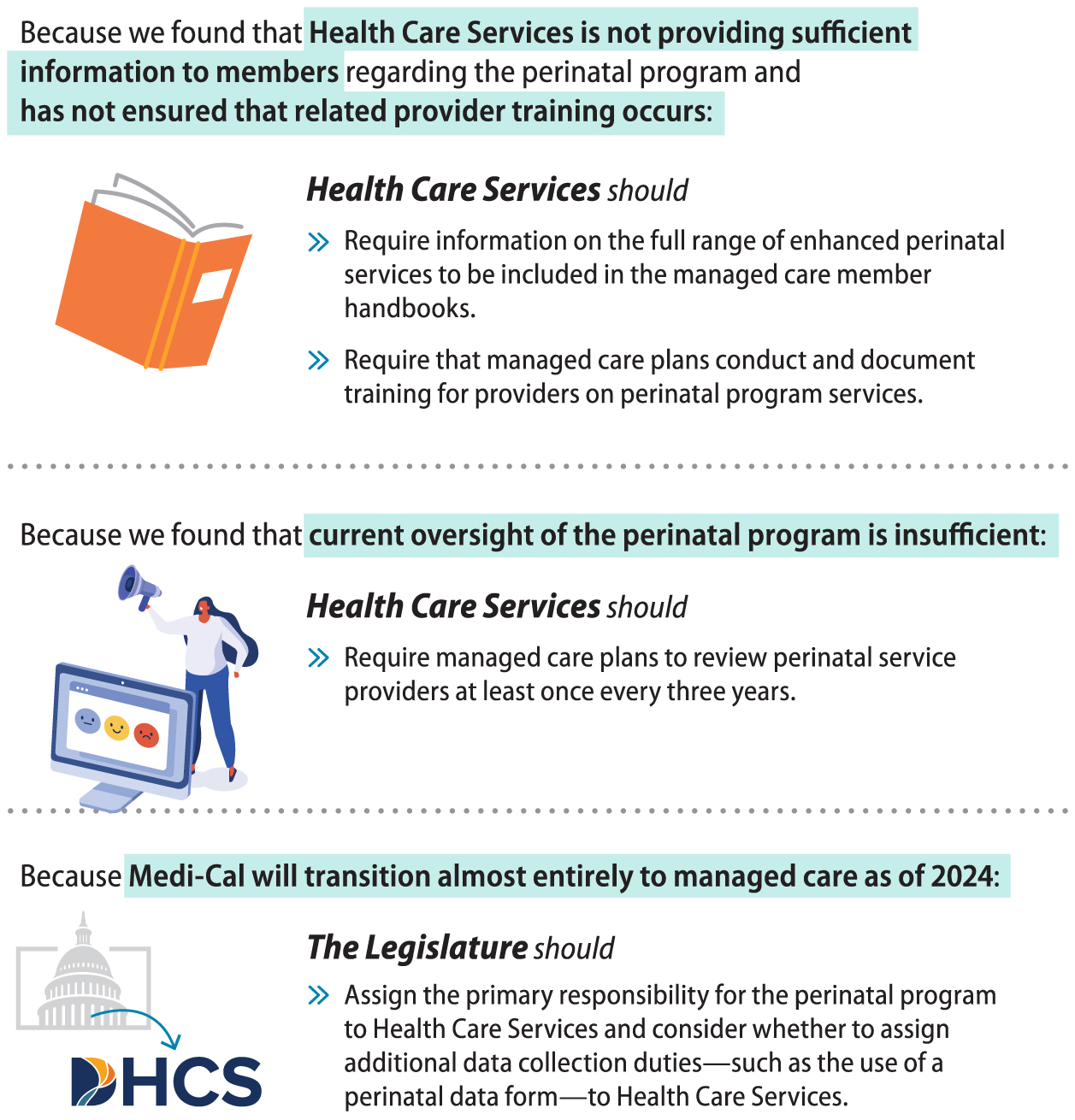

Alternatively, without more direct perinatal program administration through CalAIM or another approach such as updated regulations and requirements, the monitoring and oversight problems we have identified throughout this report are likely to continue. Neither Public Health nor Health Care Services has used their various oversight mechanisms—including provider reviews, chart reviews, and enforcement tools—to identify potential perinatal program weaknesses or ensure meaningful improvements to the program. Moreover, neither Public Health nor Health Care Services has ensured that actual and potential Medi‑Cal members entitled to the perinatal program have been sufficiently informed of its services. This increases the likelihood that Medi‑Cal members may not seek available services because they are unaware of the perinatal program, which, in turn, increases the likelihood of poor maternal and infant health outcomes. If the program is to improve, the oversight and administration of the perinatal program must change to ensure that its important benefits are effectively communicated, provided, and accurately tracked. We describe proposed improvements to the program in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Health Care Services Can Improve the Perinatal Program to Better Serve Medi‑Cal Members and Can Provide More Effective Oversight

Source: Findings and recommendations contained in Report 2023-103.

Figure 6 description:

Figure 6 is a graphic summarizing our recommendations to the Legislature and to Health Care Services, to better serve Medi-Cal members and provide more effective oversight. The graphic contains three sections. The first section includes an image of an orange booklet, and states that because we found that Health Care Services is not providing sufficient information to members concerning the perinatal program, and has not ensure that related provider training occurs, Health Care Services should require information on the full range of enhanced perinatal services to be included in the managed care member handbooks, and should require that managed care plans conduct and document training for providers on perinatal program services. The second section includes an image of a computer screen showing three smiley faces with varying emotions, and an individual with long hair holding a bullhorn. The second section states that because we found that current oversight of the perinatal program is insufficient, Health Care Services should require managed care plans to review perinatal service providers at least once every three years. The third section includes an image of the State Capitol dome with an arrow pointing to Health Care Services’ logo, and states that because Medi-Cal will transition almost entirely to managed care as of 2024, the Legislature should assign the primary responsibility for the perinatal program to Health Care Services and consider whether to assign additional data collection duties – such as the use of the perinatal data form – to Health Care Services.

OTHER AREAS WE REVIEWED

Perinatal Program Services Can Be Provided in Homes or Community Settings

Our review did not identify significant policy or regulatory restrictions that would impede perinatal program practitioners from providing program and equivalent services in homes or community settings. State law defines the practitioners who can provide most perinatal services, such as Comprehensive Perinatal Health Workers (program workers), who are provider staff with at least one year of full‑time paid practical experience in providing perinatal care. Although program workers are restricted from offering perinatal program services outside of clinics, Health Care Services generally allows perinatal services to be provided through telehealth. Additionally, Public Health also explained that program workers may conduct assessment services via telehealth. Other practitioners, as listed in the Introduction, do not have such restrictions and may provide services outside of clinics in homes and community settings. Thus, all perinatal practitioners can provide program services to Medi‑Cal members in homes and community settings, at a minimum through telehealth.

The State Specifies the Plans’ Roles and Responsibilities Related to Timely Access

It is the Legislature’s intent that Medi‑Cal managed care services are available and accessible in a timely manner. In order to meet access-to-care standards of timeliness, a plan must ensure that its network has adequate capacity and availability of providers, and the Department of Managed Health Care established regulations in this regard. In its contracts with managed care plans, we found that the State sufficiently communicates to the plans their responsibilities in providing timely access to care. To meet timely access standards for perinatal services generally, those services must be provided within either 10 or 15 business days of a request for an appointment, depending on whether the provider has elected to serve as a primary care provider.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following are the recommendations we made as a result of our audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these recommendations can be found in the Audit Results section of this report.

Legislature

To ensure the efficient and effective provision of perinatal services through Medi‑Cal, the Legislature should modify state law to assign the primary perinatal program administration and oversight responsibilities to Health Care Services, and direct Health Care Services to develop a system of oversight to ensure that providers are aware of and offer program services to all pregnant and postpartum Medi‑Cal members. As part of this update, the Legislature should consider whether to assign additional data collection duties to Health Care Services, for example by requiring the department to create and use a version of the perinatal services data form mandated by state law. Such a form could track data on perinatal services that would also make possible the department’s analysis of utilization rates. To the extent necessary, Health Care Services should then contract with Public Health to maintain any services or program oversight functions best conducted by Public Health.

Public Health and Health Care Services

To ensure effective program oversight and to acknowledge that nearly all Medi‑Cal members use managed care plans, Public Health and Health Care Services should, by January 2025, collaborate to update regulations related to the perinatal program. The regulations should include, at a minimum, a clarification of the roles and responsibilities of each department and adjustments to the current monitoring and oversight systems as described individually below to ensure that the departments provide sufficient oversight of the perinatal program.

Health Care Services

To improve its current Medi‑Cal monitoring and oversight systems, Health Care Services should do the following:

- Require managed care plans to conduct quality assurance reviews on perinatal service providers, such as OB-GYNs, at least once every three years, beginning by January 2025. If necessary, Health Care Services should seek resources to facilitate this change.

- Include the perinatal program in its risk assessment when determining where to target its annual medical audits.

To ensure that the State informs all Medi‑Cal members of the perinatal program and the enhanced services available to them, Health Care Services should, by June 2024, update its Medi‑Cal template and guidance to managed care plans to require that all member handbooks describe the enhanced perinatal program benefits. At a minimum, this language should include information on pregnancy‑related health education, nutrition counseling, and assessments and referrals for basic health needs and mental health care.

To ensure that providers are adequately trained on the requirements of the perinatal program, beginning in January 2025 Health Care Services should require that managed care plans ensure and document that providers have received training as appropriate. At a minimum, this training should include what services are available and how to document that providers offered those services.

Public Health

By December 2024, Public Health should develop and implement a system to sufficiently verify the survey responses provided by fee‑for‑service providers. For example, Public Health could conduct chart reviews annually on a selection of fee‑for‑service providers who have completed its survey to ensure the accuracy of responses. To the extent that such oversight could be provided through a partnership with Health Care Services, Public Health should seek such a collaboration.

To ensure that providers are knowledgeable about the services the perinatal program requires, by December 2024, Public Health should require that all fee‑for‑service perinatal program providers attend training on administering the perinatal program.

To comply with state law, Public Health should develop and implement a data form for use by providers to collect comprehensive information on perinatal services offered and used, the results of which should be sent to Health Care Services to gather necessary information on the program’s usage and effectiveness. At a minimum, this form should include whether providers are rendering perinatal services to Medi‑Cal members. Based in part on information collected by local health coordinators during their reviews, we developed a sample form to illustrate the type of information Public Health should collect, as shown in Appendix A.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code sections 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions, based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions, based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

February 15, 2024

Staff:

John Lewis, MPA, CIA, Audit Principal

Nick Phelps, JD, Senior Auditor

Arseniy A. Sotnikov

Emily Wilburn

Karen Wells

Mike Carri

Data Analytics:

Ryan P. Coe, MBA, CISA

Andrew Jun Lee

Legal Counsel:

David King

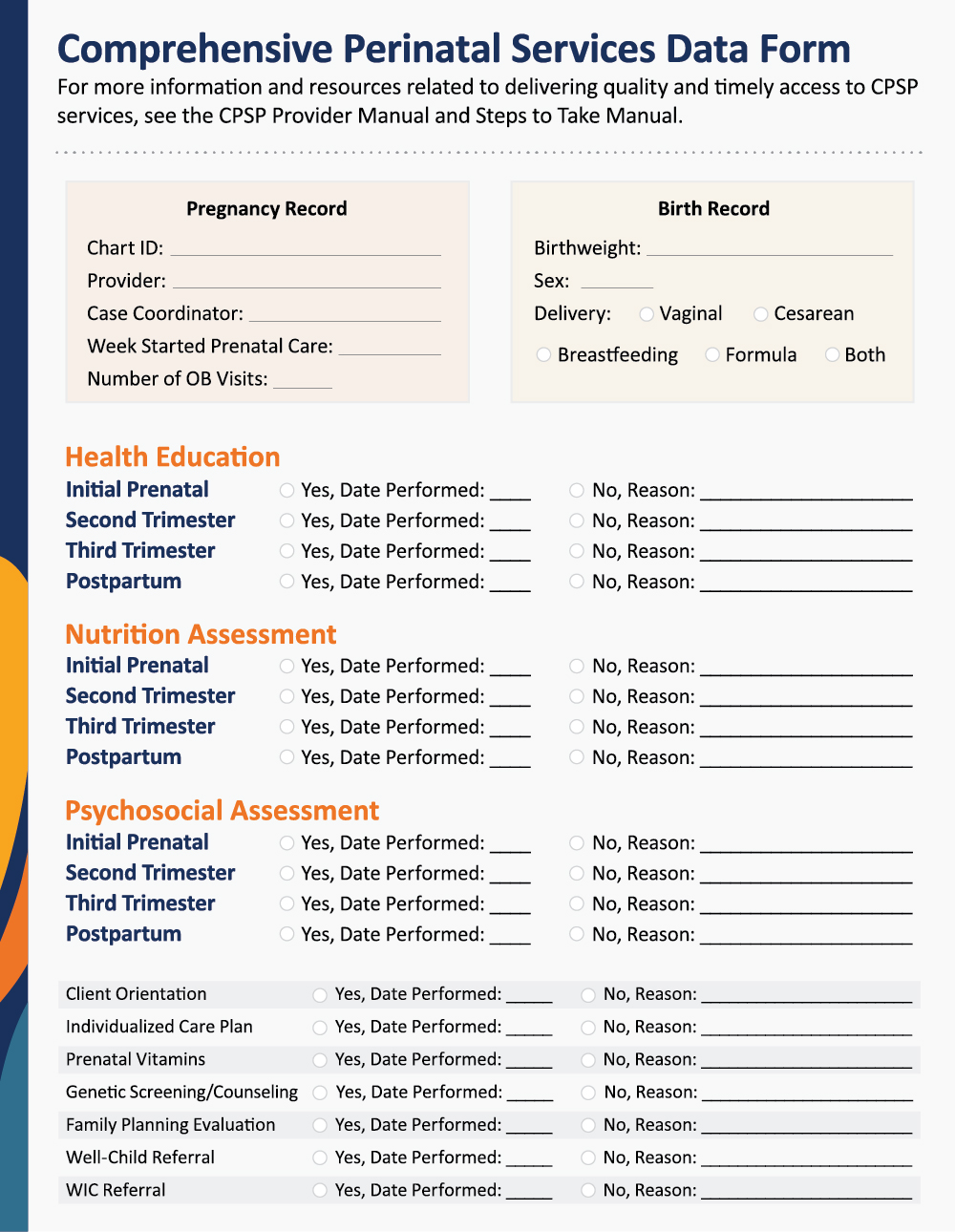

APPENDIX A

Comprehensive Perinatal Data Form

As discussed throughout the report, data related to the perinatal program are lacking. The sample perinatal form we provide on the following page, which we base in part on forms that local coordinators have used during medical record reviews, represents a method that could be used to comply with state law while simultaneously increasing the amount and usefulness of the data collected by the State. For example, the form would allow usage data to be tracked and would provide a method for communicating why any particular service was not provided. In the aggregate, this information could be used to improve the program and reduce the incidence of low birthweights.

Comprehensive Perinatal Data Form

Source: Auditor generated.

Figure A description: