2023-102.1 Homelessness in California

The State Must Do More to Assess the Cost‑Effectiveness of Its Homelessness Programs

Published: April 9, 2024

April 9, 2024

2023-102.1

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested an audit of the State’s homelessness funding, including an evaluation of the efforts undertaken by the State and two cities to monitor the cost‑effectiveness of such spending. The following report (2023‑102.1) focuses primarily on the State’s activities, in particular the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH)—while a separate report (2023‑102.2) details our findings and conclusions for the two cities we reviewed—San José and San Diego. In general, this report concludes that the State must do more to assess the cost-effectiveness of its homelessness programs.

The State lacks current information on the ongoing costs and outcomes of its homelessness programs, because Cal ICH has not consistently tracked and evaluated the State’s efforts to prevent and end homelessness. Although Cal ICH reported in 2023 financial information covering fiscal years 2018–19 through 2020–21 related to all state-funded homelessness programs, it has not continued to track and report this data since that time, despite the significant amount of additional funding the State awarded to these efforts in the past two years. Cal ICH has also not aligned its action plan to end homelessness with its statutory goals to collect financial information and ensure accountability and results. Thus, it lacks assurance that the actions it takes will effectively enable it to achieve those goals. Another significant gap in the State’s ability to assess programs’ effectiveness is that it does not have a consistent method for gathering information on the costs and outcomes for individual programs.

We also reviewed five state-funded homelessness programs to assess their cost-effectiveness. After comparing reported costs and outcomes to alternative possible courses of action, we determined that the Department of Housing and Community Development’s Homekey program and the California Department of Social Services’ CalWORKs Housing Support Program appear to be cost‑effective. However, we were unable to assess the cost‑effectiveness of three other programs we reviewed because the State has not collected sufficient data on the outcomes of these programs. Among the recommendations we make is that the Legislature mandate reporting by state agencies on the costs and outcomes of their homelessness programs and that it require Cal ICH to compile and publicly report this information.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| Cal ICH | California Interagency Council on Homelessness |

| CoC | Continuum of Care |

| CDSS | California Department of Social Services |

| ERF | Encampment Resolution Funding |

| HCD | California Department of Housing and Community Development |

| HHAP | Homeless Housing Assistance, and Prevention |

| HMIS | Homeless Management Information System |

| HUD | U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| PIT count | point-in-time count |

| SRAP | State Rental Assistance Program |

SUMMARY

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested an audit of the State’s homelessness funding, including an evaluation of the efforts undertaken by the State and two cities to monitor the cost‑effectiveness of such spending. This report (2023‑102.1) focuses primarily on the State’s activities—in particular, the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH)—and a separate report (2023‑102.2) details our findings and conclusions about homelessness spending by the cities of San José and San Diego.

More than 180,000 Californians experienced homelessness in 2023—a 53 percent increase from 2013. To address this ongoing crisis, nine state agencies have collectively spent billions of dollars in state funding over the past five years administering at least 30 programs dedicated to preventing and ending homelessness. Cal ICH is responsible for coordinating, developing, and evaluating the efforts of these nine agencies. In this audit, we reviewed the State’s efforts to track and evaluate the effectiveness of the homelessness programs that it funds, and we drew the following conclusions:

Cal ICH Has Not Consistently Tracked and Evaluated the State’s Efforts to End Homelessness

In February 2021, we reported that the lack of coordination among the State’s homelessness programs had hampered the effectiveness of the State’s efforts to end homelessness.1 Subsequently, the Legislature required Cal ICH to evaluate and report financial information related to all state‑funded homelessness programs. Cal ICH published this assessment in 2023 and it covered fiscal years 2018–19 through 2020–21; however, it has not continued to track and report on this information since that time. Further, it has not aligned its action plan for addressing homelessness with its statutory goals, nor has it ensured that it collects accurate, complete, and comparable financial and outcome information from homelessness programs. Until Cal ICH takes these critical steps, the State will lack up‑to‑date information that it can use to make data‑driven policy decisions on how to effectively reduce homelessness.

Two of the Five State‑Funded Programs We Reviewed Are Likely Cost‑Effective, but the State Lacks Outcome Data for the Remaining Three

When we selected five of the State’s homelessness programs to review, we found that two were likely cost‑effective: Homekey and the CalWORKs Housing Support Program (housing support program). Specifically, Homekey refurbishes existing buildings to provide housing units to individuals experiencing homelessness for hundreds of thousands of dollars less than the cost of newly built units. Similarly, the Housing Support Program’s provision of financial support to families who were at risk of or experiencing homelessness has cost the State less than it would have spent had these families remained or become homeless. However, we were unable to fully assess the other three programs we reviewed—the State Rental Assistance Program, the Encampment Resolution Funding Program, and the Homeless Housing, Assistance and prevention grant program—because the State has not collected sufficient data on the programs’ outcomes. In the absence of this information, the State cannot determine whether these programs represent the best use of its funds.

Agency Comments

Cal ICH agreed with our recommendations and identified actions it plans to take to implement them.

Although we did not make recommendations to the California Department of Social Services (CDSS), it indicated that it reviewed the draft report for factual inaccuracies and found none.

INTRODUCTION

Background

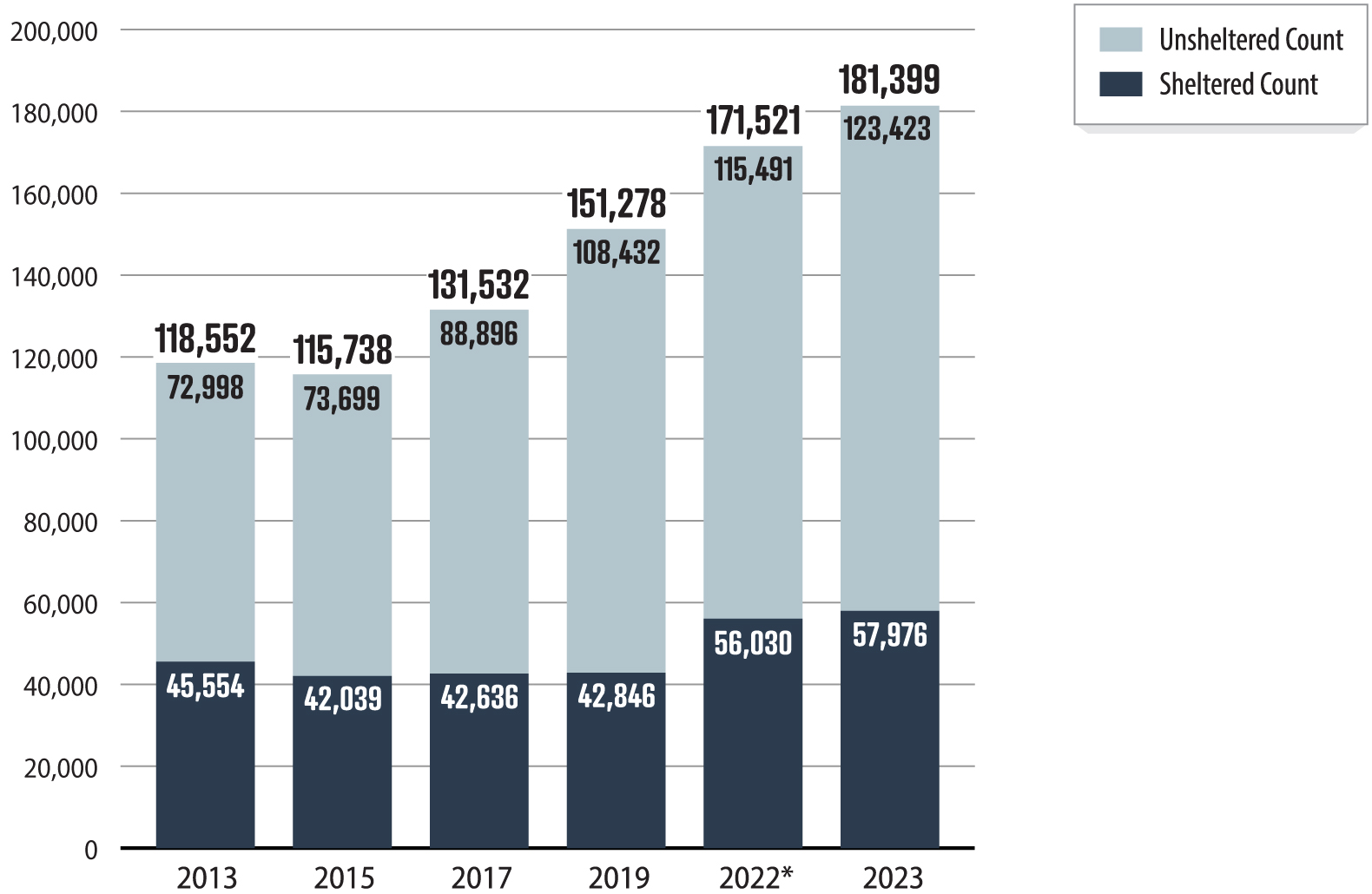

The number of people experiencing homelessness in the State has increased significantly during the last 10 years. According to federal regulations, any individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence is experiencing homelessness. When people primarily spend their nights in public or private locations not normally used for sleeping, it is considered unsheltered homelessness. When people stay in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe havens, it is considered sheltered homelessness. People experiencing homelessness face devastating challenges to their health and well‑being. For example, a study by the University of California, San Francisco from June 2023 found that two‑thirds of participants reported current mental health symptoms and that homelessness worsened participants’ mental health symptoms.2 Figure 1 shows that although the number of people experiencing homelessness in California decreased slightly from 2013 through 2015 to fewer than 116,000 individuals, it had increased to more than 181,000 individuals as of 2023.

Figure 1

California’s Population of People Experiencing Homelessness Has Increased Since 2013

Source: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) point-in-time (PIT) counts, Annual Homeless Assessment Report, and HUD memorandum.

Note: HUD requires Continuums of Care (CoCs) to conduct a PIT count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness annually and a count of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness at least biennially. To present the total number of people experiencing homelessness, we therefore used the year in which both categories of PIT counts were conducted.

* HUD waived the PIT count requirement for unsheltered homelessness in 2021 because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but it required the count again in 2022.

Figure 1 description:

Figure 1 is a bar graph that depicts the number of people experiencing homelessness in California generally increasing since 2013 through to 2023. The bar graph is a stacked bar which depicts the total count of people experiencing homelessness with two different colors in the bars. The blue-gray colored section of the bars represent the counts of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in a given year and dark blue colored sections of the bars represent the count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness in the same year. Each bar also lists the actual count within each category of homelessness culminating with the total count for that year presented on top of the bar. For example, in the bar for year 2013, the dark blue section has a count of 45,554 and the blue-gray section has a count of 72,998, and therefore the total count for that whole 2013 bar is 118,552. The years represented in the bar graph include 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022, and 2023. There was a slight decrease in the total count of people experiencing homelessness from 2013 to 2015, but the count has since continued to grow. Below the bar graph is a list of sources used and some notes further explaining where the count data originated and how we calculated total counts.

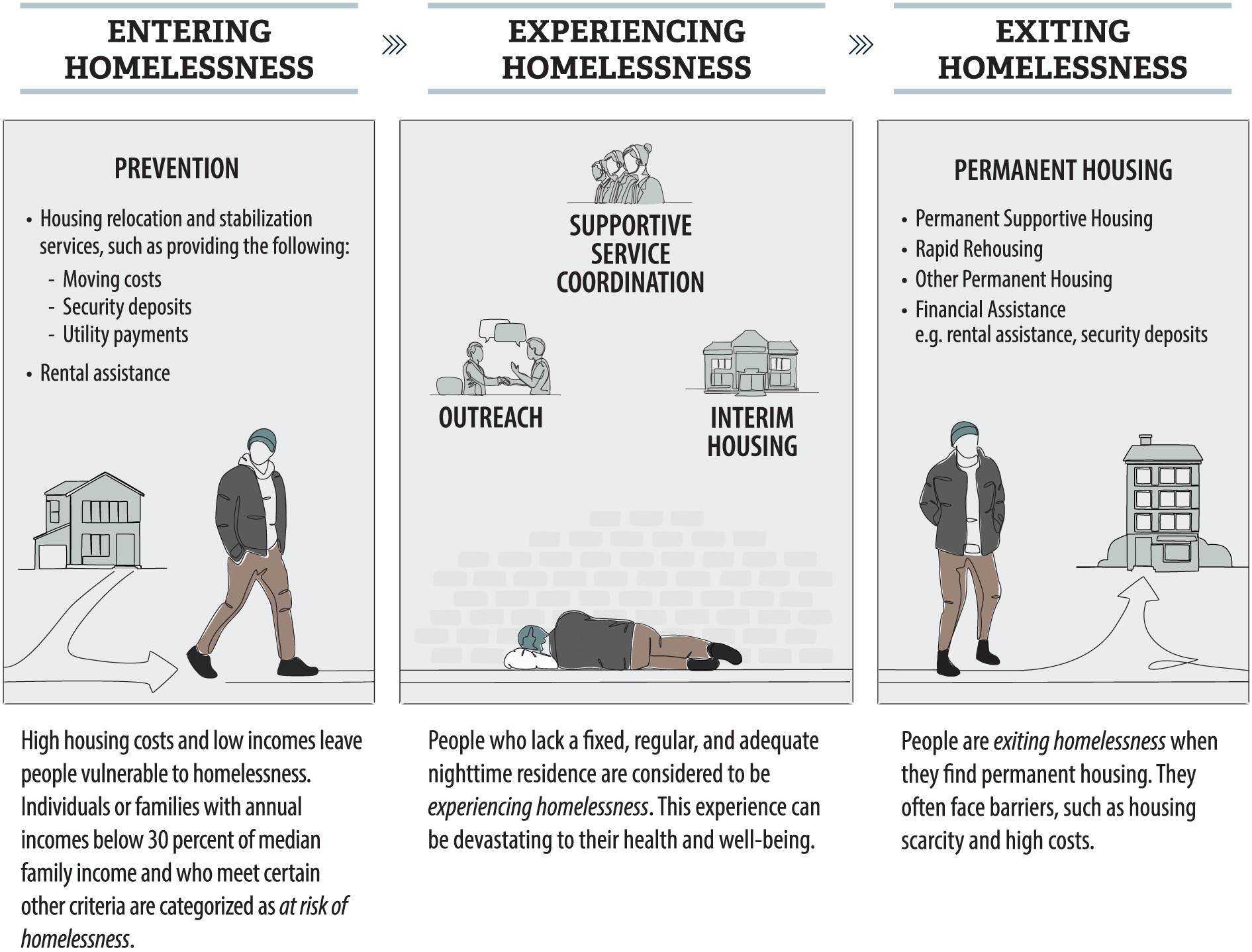

Figure 2 shows the three main phases of homelessness: entering homelessness, experiencing homelessness, and exiting homelessness. The University of California, San Francisco’s June 2023 study of people experiencing homelessness describes economic, social, and health factors that can lead to homelessness. The study found that high housing costs and low incomes had left participants vulnerable to homelessness and that the most frequently reported economic reason for entering homelessness was loss of income. Resolutions to this situation include preventing people from entering homelessness and helping people exit homelessness to live in permanent housing. Factors such as scarcity of housing, high cost of housing, lack of rental subsidies, and lack of assistance in identifying housing, create barriers to accessing housing.

Figure 2

The Three Phases of Homelessness Each Have Mitigating Solutions

Source: Federal regulations, Federal Strategic Plan, Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency documentation, and Toward a New Understanding: The California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness, a study published by the UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative in June 2023.

Figure 2 description:

Figure 2 is an image depicting how one person experiences the three phases of homelessness. In the first third of the figure, a person is depicted as losing their housing and entering homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods by which this could have been prevented. The middle part of the figure depicts the same person sleeping on the ground outside and experiencing homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods that programs can employ to mitigate the impacts of experiencing this unsheltered homelessness. The last part of the figure shows the same person finding permanent housing and exiting homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods that programs could use to help achieve this outcome.

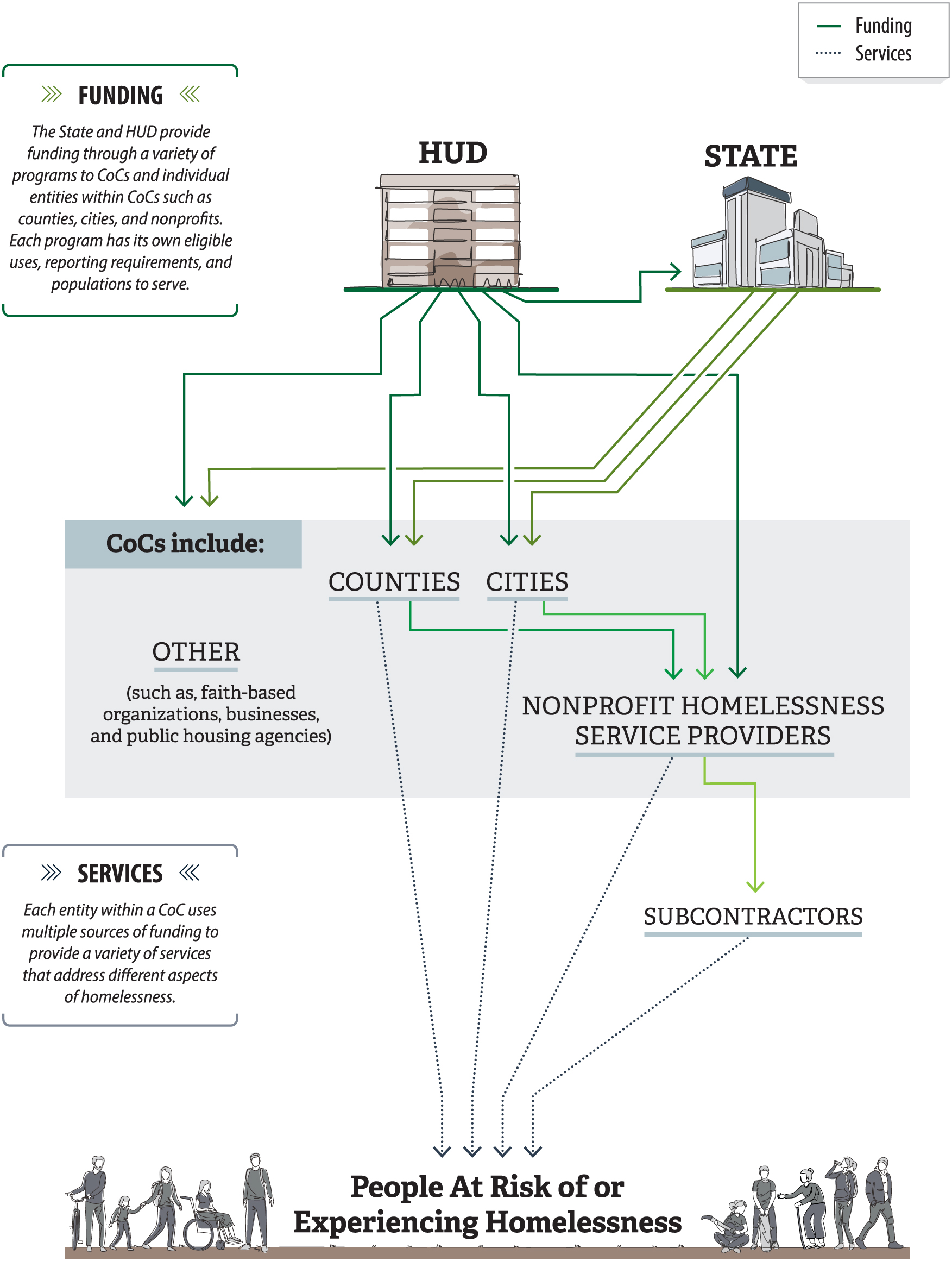

Numerous Entities Have Roles in Funding Homelessness Services in California

Numerous entities are involved in funding homelessness prevention and support services, and permanent housing in California. Federal, state, and local governments all issue funding that flows through other entities before reaching people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Most notably, the State recently increased its financial role in addressing housing affordability and homelessness. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, the State allocated nearly $24 billion for homelessness and housing during the last five fiscal years, or from 2018–19 through 2022–23.

Description of the Five Programs We Reviewed

Homekey: Created as an opportunity for local public agencies to purchase motels and other housing types to increase their communities’ capacity to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The target population was individuals and families who are experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness.

Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention (HHAP): Provides local jurisdictions with funds to support regional coordination and expand or develop local capacity to address their immediate homelessness challenges.

State Rental Assistance Program (SRAP): Provides funds for rental arrears, prospective rental payments, utility and home energy cost arrears, utility and home energy costs, and other expenses related to housing incurred during or due, directly or indirectly, to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eligible households must demonstrate a risk of homelessness or housing instability.

Encampment Resolution Funding (ERF): Provides competitive grants to assist local jurisdictions in ensuring the wellness and safety of people experiencing homelessness in encampments by providing services and supports that address their immediate physical and mental wellness and result in meaningful paths to safe and stable housing.

CalWORKs Housing Support Program (housing support program): Offers financial assistance and housing‑related wraparound supportive services, including rental assistance and case management. The program serves families with children enrolled in CalWORKs who are at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

Source: State law and program documentation.

Nine different state agencies funded and administered over 30 programs geared toward preventing and ending homelessness.3 These programs deliver a wide range of services, including creating temporary shelters, providing mental health treatment, and addressing encampments of those experiencing homelessness.4 As part of this audit, we reviewed the five state programs that the text box describes. We selected these programs based on multiple factors, including program funding amounts and services offered. Some of these programs initially received one‑time funding. If the Legislature provided a program with subsequent appropriations of one‑time funding, then this is referred to as a round. For example, the Legislature originally appropriated $650 million in one‑time funding in 2019 for the HHAP program, which was called HHAP Round 1. The Legislature has since approved more than $3 billion in additional funds through four subsequent rounds.

CoCs Are Central to California’s Provision of Homelessness Services

As Figure 3 shows, CoCs are central to the provision of homelessness services in California. In 1993 HUD established the CoC system. A CoC is a group composed of individuals and organizations, such as homeless service providers, cities, and counties, formed pursuant to federal regulations and recognized by the federal government to achieve the goal of ending homelessness within a geographic area. Congress codified the CoC system into law to promote communitywide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness by providing funding for the efforts of states, local governments, and nonprofit service providers to quickly re‑house people experiencing homelessness. The 44 CoCs that cover California’s 58 counties provide regional collaboration among member entities, including cities, but do not direct the actions of those member entities. The State and HUD provide funding through a variety of programs to CoCs and to the entities within CoCs, such as counties, cites, and nonprofits. Those entities are responsible for following the eligible uses and reporting requirements of the funding they receive.

Figure 3

There Are Many Layers to Homelessness Funding and Services

Source: State law; grant agreements; documentation from Cal ICH, HUD, CDSS, HCD, cities, and counties; and a service provider’s website.

Figure 3 description:

Figure 3 is an organizational chart that depicts the many agencies involved in homelessness funding and services and how the funding flows through these agencies to eventually reach people experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness through the provision of services. There are arrows connecting all the layers which depict either the flow of funding through solid green colored arrows or the flow of services through dotted arrows. At the top layer of the figure are images representing the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the government of the State of California. As shown through solid green colored arrows, HUD provides funding to the State as well as directly to Continuums of Care (CoCs) and entities within CoCs. The State also provides funding to CoCs and entities within CoCs, also shown through the directions of solid green arrows. The middle layer of the chart depicts CoCs and entities within CoCs, specifically Counties and Cities, receiving funding from HUD and the State. The middle layer of the chart also depicts Nonprofit Homelessness Service Providers within CoCs receiving funding from HUD, Counties, and Cities, also shown through the directions of solid green arrows. The last layer of the figure depicts Nonprofit Homelessness Service Providers giving funding to subcontractors shown by the direction of a solid green arrow as well as providing services directly to people at risk of or experiencing homelessness shown by the direction of a dotted arrow. The last layer also shows people at risk of or experiencing homelessness receiving services from the cities and counties directly as well, which are again shown by the directions of dotted arrows.

Local jurisdictions and nonprofit service providers deliver various services that include identifying the needs of people experiencing homelessness, placing them into temporary shelters, providing them with supportive services, and funding housing for them. Data show that nearly 316,000 individuals experiencing homelessness accessed housing and services in California’s 44 CoCs in 2022.5 The COVID‑19 pandemic, which occurred during the period we reviewed, had significant effects on homelessness and resulted in substantial funding being made available to address the crisis.

The CoCs are also responsible for counting individuals who are experiencing homelessness. Specifically, to identify the number of people experiencing homelessness, HUD requires annual PIT counts of those experiencing sheltered homelessness and biennial counts of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness. On a single night in January, CoCs attempt to count the number of people, sheltered and unsheltered, experiencing homelessness. The information collected during the PIT count is critical. Specifically, it is the main source of data used by the federal government to track the number of people experiencing homelessness and to determine federal funding allocations to address homelessness. Additionally, states and local jurisdictions rely on PIT count data to inform their strategic planning efforts, funding allocations, and the effectiveness of homeless programs.

Cal ICH Coordinates, Evaluates, and Develops the State’s Efforts to Prevent and End Homelessness

The Legislature created Cal ICH by statute in 2017 to coordinate the State’s efforts to prevent and end homelessness. As the top text box describes, Cal ICH (originally named the Homeless Coordinating and Financing Council) is composed of representatives from 18 different state entities as well as two members appointed by the Legislature from stakeholder organizations. Cal ICH’s responsibilities are in the 19 statutory goals that the Legislature has established. Some of these statutory goals include making policy and procedural recommendations to the Legislature, and collecting, compiling, and making available to the public financial data provided to Cal ICH from all state funded homelessness programs. Cal ICH is led by an executive officer and staffed by more than 40 employees.

Cal ICH Includes Leaders or Representatives From 18 State Entities and Two Appointed Members

- Business, Consumer Services and Housing Agency

- California Health and Human Services Agency

- California Department of Transportation

- California Department of Housing and Community Development

- California Department of Social Services

- California Housing Finance Agency (CalHFA)

- Department of Health Care Services (DHCS)

- California Department of Veterans Affairs

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR)

- California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC)

- California Department of Public Health

- California Department of Aging

- Department of Rehabilitation

- Department of State Hospitals

- California Workforce Development Board

- California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES)

- California Department of Education

- California Community Colleges (CCCCO), University of California, or California State University

- Two appointments from stakeholder organizations

Source: State law.

In 2021 Cal ICH adopted an Action Plan for Preventing and Ending Homelessness in California (action plan) to orient the State’s efforts and updated it in 2022 and again in 2023. The action plan details five action areas, which the text box lists. These action areas are divided into objectives, which are further divided into activities. Cal ICH also published a Statewide Homelessness Assessment (homelessness assessment) in 2023 for the Legislature. The Legislature’s intent in requesting this assessment was to obtain trustworthy information to connect funding allocated to prevent and end homelessness with established sheltering and housing resources, and to provide state agencies with accurate information for more precise forecasting to target future investments. The homelessness assessment covered fiscal years 2018–19 through 2020–21 and reported how State funds were used to provide housing and services to people experiencing homelessness, demographic information about the population served by these programs, the types of services provided, and the outcomes of the programs. The report found that the State has expanded its role in addressing homelessness by investing in new programs—increasing its investment in homelessness‑focused programs by more than $1.5 billion, from $2.3 billion in fiscal year 2018–19 to $3.8 billion in 2020–21. Appendix A presents information about the programs and funding identified in the homelessness assessment.

Action Plan’s Five Action Areas

- Strengthening our systems to better prevent and end homelessness in California.

- Equitably addressing the health, safety, and service needs of Californians experiencing unsheltered homelessness.

- Expanding communities’ capacity to provide safe and effective shelter and temporary housing.

- Expanding and ensuring equitable access to permanent housing in our communities.

- Preventing Californians from experiencing the crisis of homelessness.

Source: Cal ICH’s 2021 action plan and 2022 and 2023 updates.

In addition, Cal ICH administers several grant programs intended to prevent and end homelessness, such as HHAP and the ERF program. However, the Legislature intends to transfer all grant programs administered by Cal ICH to the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) by July 2024. This transfer is intended to allow Cal ICH to better focus its efforts on providing statewide policy development and coordination.

CoCs Collect Data About Homelessness in Local Information Systems

Federal regulations require each CoC to use a Homeless Management Information System (HMIS)—a local information technology system in which recipients and subrecipients of federal funding record and analyze client, service, and housing data for individuals and families at risk of or experiencing homelessness. The CoCs must designate a lead agency to operate the HMIS, and that lead agency must comply with HUD’s requirements for data collection, management, and reporting. In alignment with HUD’s requirements, the text box shows that CoCs collect certain data from entities that provide services to people experiencing homelessness. These services include the project types of homelessness prevention, street outreach, emergency shelter, and rapid re‑housing. The CoCs also collect demographic data about the people who access these services.

Examples of Data Collected

- Project Type

- Participant Demographics

- Participant Living Situation

- Project Funding Source

- Project Start and Exit Date

- Project Location

Source: 2024 HMIS Data Standards Manual.

In 2021 Cal ICH launched the State’s Homeless Data Integration System (state data system). This Cal ICH data system securely collects data from each local HMIS. Cal ICH intended to provide the State with data that it can analyze to make data‑driven policy decisions to prevent and end homelessness in California. Individual CoCs send data from their local HMIS to the state data system quarterly. Cal ICH’s data system aggregates data from HMISs, including client‑level data.

ISSUES

Cal ICH Has Not Consistently Tracked and Evaluated the State’s Efforts to End Homelessness

Key Points

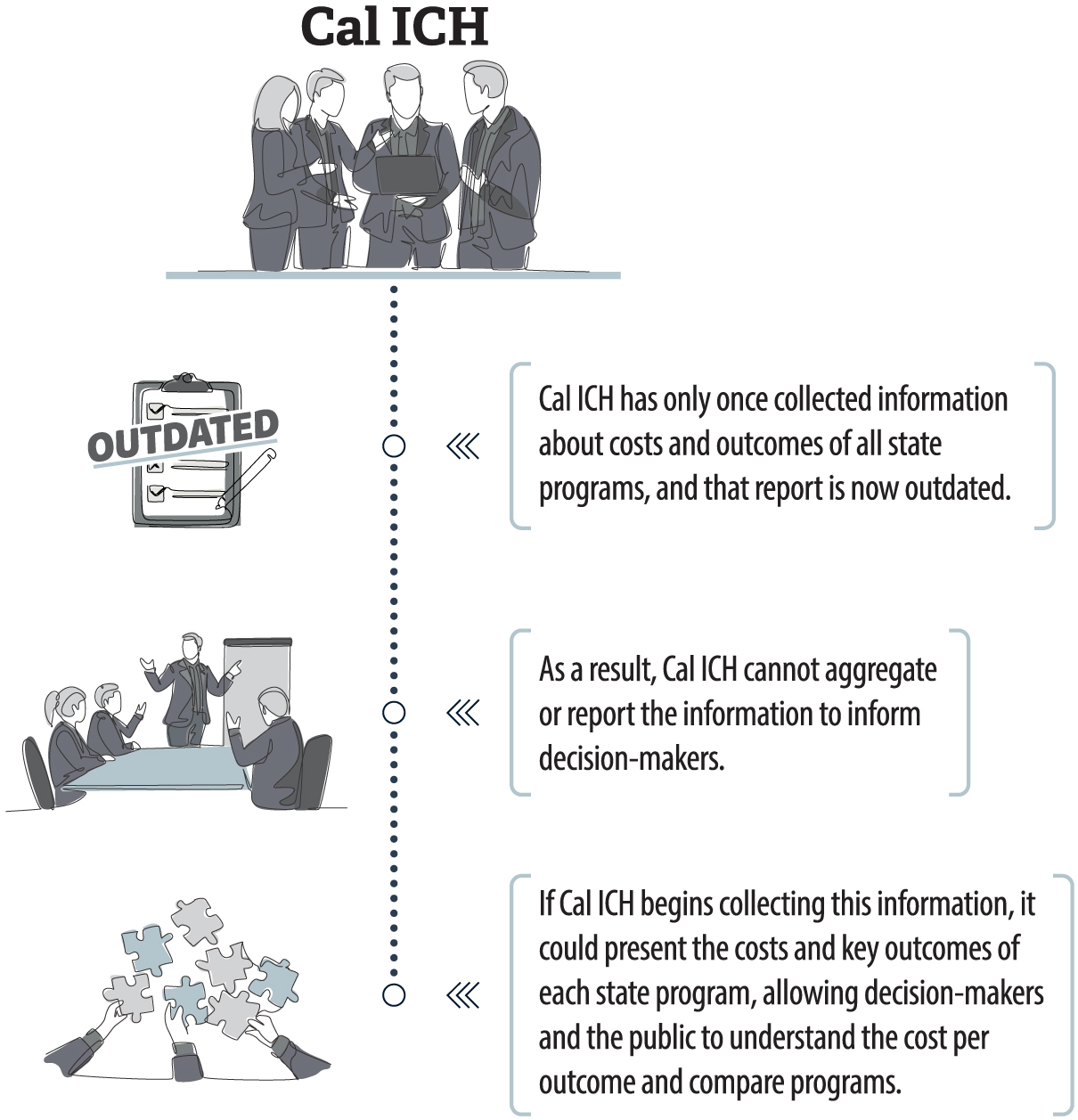

- Cal ICH has not tracked and reported on the State’s funding for homelessness programs statewide since its 2023 assessment covering fiscal years 2018–19 through 2020–21. Currently, it has no plans to perform a similar assessment in the future. In the absence of an up‑to‑date assessment, the State and its policymakers are likely to struggle to understand homelessness programs’ ongoing costs and achieved outcomes.

- Cal ICH has not aligned its action plan with its statutory goals. Consequently, it lacks assurance that the actions it takes will effectively enable it to reach those goals.

- Cal ICH has not established a consistent method for gathering information on homelessness programs’ costs and outcomes. As a result, the State lacks information that would allow it to make data‑driven policy decisions and identify gaps in services.

- Cal ICH has neither ensured the accuracy of the information in the state data system, nor has it used this information to evaluate homelessness programs’ success.

Cal ICH Has Not Regularly Tracked Statewide Homelessness Funding

From July 2018 through June 2021, the State allocated billions of dollars in public funds to address homelessness. Given the financial resources the State has dedicated to reducing homelessness, transparency and accountability regarding its efforts are crucial. Nonetheless, in February 2021, we reported that the lack of coordination among the State’s homelessness programs had hampered the effectiveness of the State’s efforts to end homelessness.6 We recommended at that time that Cal ICH collect and track funding data on all state homelessness programs. Subsequently, the Legislature set a goal in September 2021 for Cal ICH to report to the public the financial information of the State’s homelessness programs. Cal ICH’s goal to collect, compile, and make available to the public financial data from all state‑funded homelessness programs is the most recent of 19 statutory goals that the Legislature has established for Cal ICH since it was created in 2017.

Collecting and reporting all state homelessness programs’ financial data allows for more complete and timely information about the State’s overall spending on homelessness. It also makes possible greater coordination of homelessness programs’ funding and may enable cost‑effectiveness comparisons. However, the law does not specify when or how often Cal ICH should report these data. In the absence of such requirements, Cal ICH has only done so once, as Figure 4 shows. Specifically, in response to separate legislation, Cal ICH conducted a one‑time statewide assessment of state‑administered programs and funding (homelessness assessment), covering the period of July 2018 through June 2021.

Figure 4

Cal ICH Does Not Regularly Collect Cost and Outcome Information, Limiting Its Evaluation of Effectiveness

Source: Analysis of state law and Cal ICH documentation.

Figure 4 description:

Figure 4 is a figure with images and text that describes Cal ICH’s actions that have limited its evaluation of the effectiveness of state programs meant to address homelessness. At the top of figure is an image of a group of people meant to represent those that makeup the Cal ICH. The next part of the figure is an image that shows that Cal ICH’s only report on the costs and outcomes of state programs is outdated. The next part of the figure is an image of Cal ICH personnel depicting them as being inhibited from aggregating and evaluating program data to provide to decision-makers across the state. The final part of the figure is an image of puzzle pieces being put together that is meant to represent the benefits of Cal ICH collecting program data, specifically the cost per program outcome which could be used to compare programs on an ongoing basis.

Cal ICH believes the homelessness assessment fulfills the statutory goal. However, those results are now nearly three years old and out of date. Since the homelessness assessment, the State has awarded a significant amount of additional funding and created new homelessness programs that the assessment does not address.

If Cal ICH does not conduct these types of assessments on a periodic basis, the State will continue to lack complete and timely information about the ongoing costs and associated outcomes of its homelessness programs. We believe that the State’s policymakers and the public need up‑to‑date information to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of billions of dollars in state spending. Appendix A lists the State’s programs and funding amounts in the homelessness assessment.

Cal ICH Did Not Address Certain Statutory Goals in Its Action Plan

Cal ICH adopted an action plan in 2021 for achieving its statutory goals, and it updated that plan in 2022. Cal ICH’s plan outlines five action areas—shown previously in the text box—and presents objectives and specific activities for preventing and ending homelessness. However, the action plan does not define the efforts Cal ICH will take toward specific statutory goals, including those involving funding and outcomes. For example, none of the action plan’s listed objectives addresses Cal ICH’s statutory goals to collect financial information or ensure accountability and results. As a result of this misalignment, Cal ICH may achieve the plan’s objectives yet still not consistently deliver on the Legislature’s goals.

The action plan’s key performance measures—which the text box lists—are similarly misaligned. Although these performance measures could be useful, they do not provide insight on specific program outcomes. Without such insight, Cal ICH again cannot fully achieve its statutory goal of ensuring accountability and results. Measuring program‑specific outcomes would allow Cal ICH to identify successful programs worthy of replicating and help policymakers prioritize investment.

Key Performance Measures From Cal ICH’s Action Plan

- The number of Californians experiencing sheltered and unsheltered homelessness at a point in time, including veterans, people experiencing chronic homelessness, families with children, adults, and unaccompanied youth.

- The number of Continuums of Care in California reporting increases versus decreases in the number of people experiencing sheltered and unsheltered homelessness within annual PIT counts.

- The number of people spending time in emergency shelter and transitional housing in California annually, including veterans, people experiencing chronic homelessness, families with children, adults, and unaccompanied youth.

- The number of Californians experiencing homelessness for the first time each year.

- The number of Californians successfully exiting homelessness each year.

- The number of Californians returning to homelessness each year.

- The number of children and youth experiencing homelessness at some point during the school year in California, including students in families and unaccompanied students.

- Comparison of California’s performance across these measures and data points to national and regional trends.

Source: Cal ICH’s Action Plan update 2022.

Cal ICH’s executive officer explained that the council recognizes that it needs to be led by its statutory goals. However, she also explained that its next updated plan may not include the statutory goals. Until Cal ICH aligns its action plan with its statutory goals, it may struggle to ensure that it meets those goals. To improve transparency and accountability for state spending, we recommend that the Legislature direct Cal ICH to require state agencies to report to it annually about homelessness spending and associated outcomes.

Cal ICH Has Not Established a Consistent Methodology for Gathering Information on Programs’ Costs and Outcomes

Cal ICH has not established a central reporting method that is consistent across all of the State’s homelessness programs and provides uniform specifications for the data they report. The law that established Cal ICH does not require state agencies to report to it the funding and outcome information on all state homelessness programs they administer. Consequently, state agencies report their program costs and outcomes using a variety of methods that cannot be readily compared, including online dashboards and written reports to the Legislature.

Programs also collect different types of data. For example, Homekey is a program that is focused on building housing for people experiencing homelessness. The program required Homekey Round 1 grantees to report on the number of properties they produced and the location of these properties. HHAP—a different program than Homekey—also provides funding to grantees that could be used to develop housing, but the law that established that program did not require Round 1 grantees to report on the location of properties built with HHAP funds.

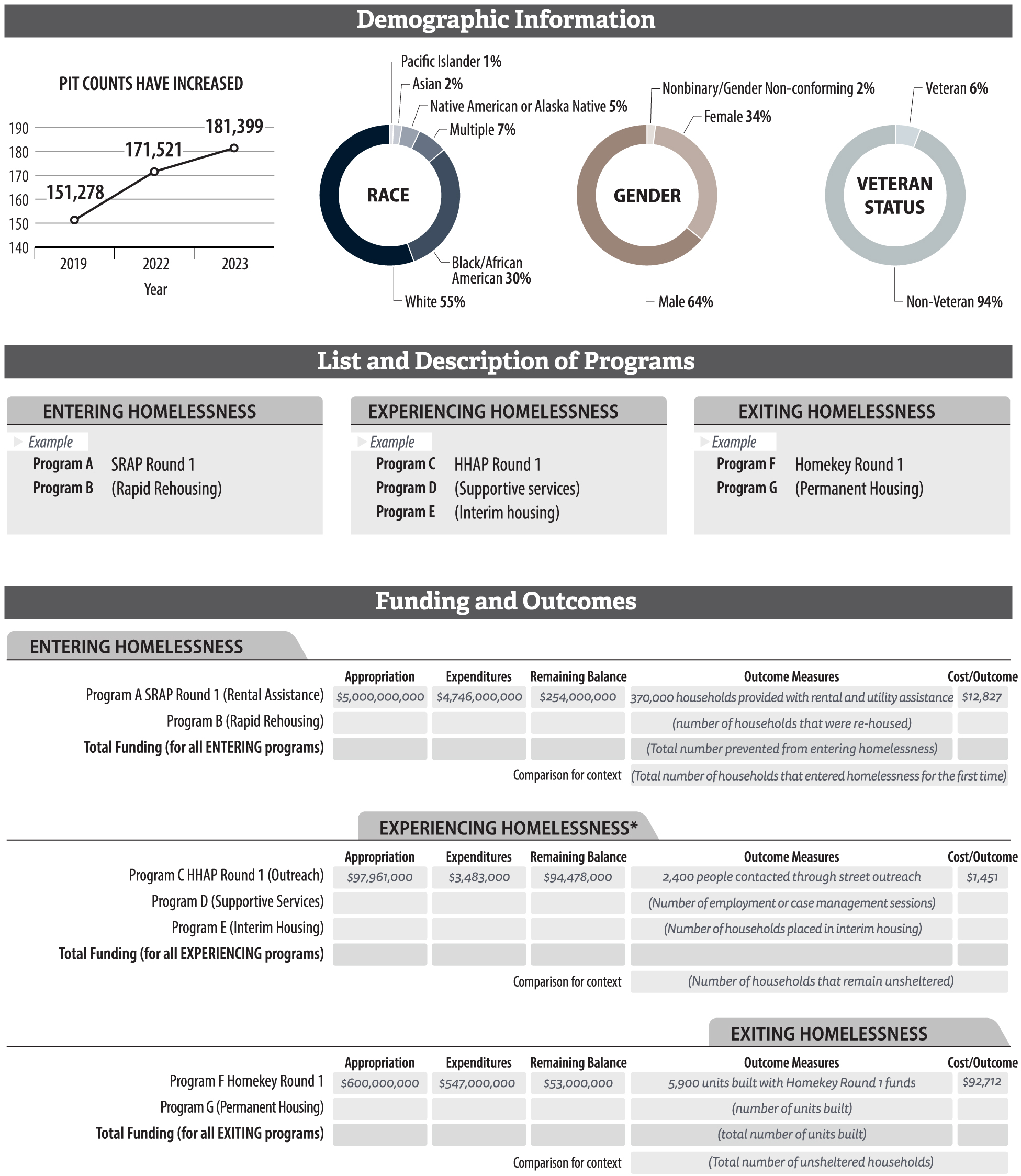

State law requires state agencies to provide any relevant information about state homelessness programs upon request of Cal ICH, positioning Cal ICH to collect these data. To more usefully gather and report program costs and outcomes and to better facilitate policy discussions, Cal ICH could develop a scorecard similar to the one we present in Figure 5. Agencies could use it to report their program funding and performance outcome information to Cal ICH. For example, a program that provides interim housing could report the number of people experiencing homelessness whom the program placed in housing and the number who received case management services.

Figure 5

Cal ICH Could Use This Hypothetical Example of a State Homelessness Program Scorecard

Source: Analysis of Cal ICH data and HCD data.

Note: Data in the example scorecard is included only for illustrative purposes and does not represent actual program data.

* In this category, the services are more distinct and could be totaled individually: if there are four programs for interim housing there could be a different total specific to interim housing.

Figure 5 description:

Figure 5 is a depiction of a hypothetical example of a state homelessness program scorecard separated by the three phases of homelessness and includes categories that would allow the user to organize and determine the cost per outcome of a specific state homelessness program. The top part of the scorecard figure shows hypothetical demographic information and includes a line graph being used to show a trend in PIT counts increasing and also three pie charts to show the hypothetical breakdown of certain demographic characteristics of the hypothetical population experiencing homelessness. There is one pie chart for racial distribution, one pie chart for gender distribution, and one pie chart for the distribution of veteran status in the hypothetical population. The middle part of the figure is for a list and description of programs being evaluated. The hypothetical programs that mitigate the impacts of homelessness are divided by their categorization into one of the three phases of homelessness. The three phases of homelessness are entering homelessness, experiencing homelessness, and exiting homelessness. The last part of the scorecard figure again lists the hypothetical programs under their specific phase of homelessness, but now also includes the programs’ hypothetical funding and outcomes. Each program has spaces for the entry of information on how much funding was appropriated to the program, how much was spent on the program, and how much funding remains to be spent. Each program also has spaces for the entry of information on the outcomes of each program. Lastly, each program has space for the calculation of the cost per program outcome based on the information organized in the previous spaces. Once all the programs that fall under one specific phase of homelessness have been individually assessed, the programs in that category can be compared as a whole against a trend or amount relevant to that phase of homelessness. For example, once the overall effect of all programs meant to prevent people from entering homelessness has been calculated, then that amount can be compared to the number of people who nonetheless entered homelessness for the first time in that same time period.

To enable comparisons among similar types of programs, Cal ICH could categorize programs according to the phase of homelessness that the programs address: entering, experiencing, or exiting homelessness. This categorization would allow the State to identify gaps in its efforts or funding to address these three phases. The Legislature could then use the scorecard to make data‑driven policy decisions and to more easily make inquiries about why funding appropriated for certain programs is not fully spent and the anticipated timing of such spending.

Cal ICH Has Not Ensured the Accuracy of the Data in the State Data System

As we previously discuss, Cal ICH has not established a statewide methodology for state‑funded homelessness programs to report their outcomes. However, Cal ICH has access to some program data through the state data system, which collects records from local CoC’s HMIS. State law requires that, beginning in January 2023, grantees or entities operating any of 10 specific homelessness programs existing as of 2021 to report to HMIS information about the services individuals receive, such as start dates, end dates, and exit destinations—grantees are not required to report cost information to HMIS. The 10 programs include Homekey, HHAP, and the CalWORKs Housing Support Program—three of the five programs we reviewed and describe in the next section of this report. All programs that began after July 1, 2021, are also required to report this information; thus, Cal ICH now generally collects some data related to several homelessness programs using the state data system.

Nonetheless, Cal ICH has not used the reporting programs’ data to evaluate the programs’ success in reducing homelessness. Although it has performed some research about the types of services received by various populations among those experiencing homelessness, it has not used the data to determine the effectiveness of any particular program. Instead, Cal ICH uses the data to populate a public-facing dashboard. The dashboard displays the number of people experiencing homelessness that each CoC served, provides information about services provided, and displays the age, race and ethnicity, gender, and veteran status of those who received the services.

Because Cal ICH does not analyze the available data to determine program effectiveness, it cannot provide critical information that state policymakers could use when prioritizing funding decisions for the myriad state homelessness programs. The executive officer of Cal ICH explained that the council intends to assess the effectiveness of state homelessness programs, but she did not provide us with any tangible plans or evidence of efforts to initiate such an assessment.

If Cal ICH begins using the available data in more meaningful ways, it will need to take steps to ensure those data are reliable. In fact, we identified a number of problems with the data in the state data system. For example, the CoC for Santa Clara County, which includes San José, provided all records from its HMIS to Cal ICH, including those that the CoC had marked as deleted. The CoC explained that some records were deleted because they were created in error. However, Cal ICH asserted that it treated at least some of the deleted records as valid and included them in publicly reported information. Similarly, in multiple CoCs statewide we found a small number of likely fictitious clients. For example, we identified more than 100 enrollment records with client names such as “Mickey Mouse,” “Super Woman,” or a name indicating it was a test client, such as “Test Participant.” While this is a small number of entries that are likely system test entries or erroneous records that were never removed, the true magnitude of such records is unknown because a CoC could enter similar records using any name. Nonetheless, Cal ICH was unaware of any test records in the data.

We also identified questionable entries in the state data system’s bed inventory and enrollment data, with some shelters showing enrollment numbers significantly over their bed capacity. In one example, a shelter reported nearly 1,100 people enrolled in fewer than 300 beds. When we asked about these entries, Cal ICH staff explained that enrollment records do not always show when individuals stopped receiving services. As a result of these errors, some of the enrollment numbers we present in this report may be overstated.

Although Cal ICH takes steps to adjust the data to improve the data quality when reporting certain metrics, such as excluding records with known illogical values, and these steps result in what Cal ICH believes is the correct data, the corrections do not necessarily result in a reflection of what actually occurred. In fact, Cal ICH did not correct for all of the errors we identified. Cal ICH staff recognize that the accuracy and completeness of the data depends on the information that each CoC records and submits to Cal ICH. Therefore, Cal ICH should work with the CoCs to ensure that they submit appropriate data.

Cal ICH’s statutory goals give it specific responsibilities as the State’s primary resource for homelessness policy coordination and accountability. However, it has also been directly managing multiple large grant programs as mandated by statute, including the multibillion‑dollar HHAP program and the more‑than‑$700 million ERF program. The Legislature appeared to recognize this focus in 2023 when it passed legislation transferring responsibility for the grant programs from Cal ICH to HCD, effective July 2024, which will likely allow Cal ICH to focus its efforts on meeting its statutory goals. Cal ICH’s executive officer acknowledged that changes in key leadership roles and in programmatic statutory language have hindered the council’s ability to meet its statutory goals.

Two of the Five State‑Funded Programs We Reviewed Are Likely Cost‑Effective, but the State Lacks Clear Outcome Data for the Other Three

Key Points

- Data indicate that two of the five programs we reviewed—Homekey and the Housing Support Program—are likely cost‑effective. Homekey allows the State to provide individuals with housing that is less expensive than newly built units. The Housing Support Program helps house families who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and costs less than the State would spend if these families were homeless.

- The State has not collected adequate outcome data to assess the cost‑effectiveness of the remaining three programs. Without such data, it will lack assurance that these programs represent the best use of state funding.

Both Homekey and the Housing Support Program Are Likely Cost‑Effective Approaches to Addressing Homelessness

When considering how best to spend the public’s money, the State’s policymakers should have the information necessary to compare program costs and outcomes. To determine the cost‑effectiveness of the state‑funded efforts to address homelessness, we reviewed the five programs we described in the Introduction. We selected these programs by considering the amount of funding provided, and the types of assistance the programs offered. We found that two of the five—Homekey and the Housing Support Program—were likely cost‑effective.

We reached this conclusion by reviewing the reported outcomes and costs of a selection of projects and services funded by each program. We then identified alternative possible courses of action to compare for cost‑effectiveness. As we discuss in the next section, we did not have the data necessary to fully assess the other three, either because the programs were recently implemented or because program staff had not collected sufficient information on program outcomes.

Homekey

Department: California Department of Housing and Community Development

Year established: 2020

Funding: Round 1–$846 million; Round 2–$1.95 billion; Round 3–$817.3 million

Number of Recipients: Round 1–94; Round 2–116

Eligible uses: To convert existing buildings into housing for people experiencing homelessness.

- Acquisition or rehabilitation of motels, hotels, or hostels.

- Master leasing of properties.

- Acquisition of other sites and assets with existing residential uses, such as care facilities.

- Conversion of units from nonresidential to residential.

- Purchase of affordability covenants and restrictions for units.

- Relocation costs for individuals who are being displaced as a result of rehabilitation of existing units.

- Capitalized operating subsidies.

Source: State law and Homekey funding notices.

As we previously explain, Homekey—which focuses on converting existing buildings into housing units for people at risk of or experiencing homelessness—appears cost‑effective when compared to the cost of building new affordable housing units. This saves time and money and allows Homekey to create more units and house more people. Table 1 shows the cost‑effectiveness comparison for Homekey.

We reviewed eight Homekey projects that received funding from Round 1 of the program. To calculate the average cost to produce a Homekey unit, we divided the amount of funds spent by the number of units the project was expected to produce. The average cost per unit for the eight projects we reviewed was about $144,000. A project in San Francisco had the highest per‑unit cost of about $200,000, whereas a project in Fresno had the lowest per‑unit cost of about $90,000 per unit.

These costs are significantly lower than the costs of building other affordable housing in the State. HCD compared the cost of Homekey housing to other affordable housing, reporting to the Legislature in 2021 that the average cost of one unit of newly built affordable housing in California in 2019 ranged from about $380,000 to $570,000, while the average cost of a Homekey unit in HCD’s analysis was $129,000. This information aligns with the average we calculated for the eight projects we reviewed. In some parts of the State, such as the Bay Area, a newly built affordable housing unit can reportedly cost up to $1 million.

HCD’s assistant deputy director explained that the program was more cost‑effective and faster than building new construction units, and that data from Round 1 Homekey projects informed HCD’s decisions in the program’s subsequent funding rounds. For example, the State increased the time it allowed Round 2 projects to rehabilitate acquired units and ensure they were substantially occupied from three months to 15 months.

Although Homekey Rounds 2 and 3 have the potential to be as cost‑effective as Round 1, those rounds are still in progress. Until the data are available on units built and people housed, we cannot fully determine the cost‑effectiveness of these rounds.

CalWORKs Housing Support Program (housing support program)

Department: California Department of Social Services

Year Established: 2014

Funding: FY 2019–20: $95 million; FY 2020–21: $95 million; FY 2021–22: $285 million; FY 2022–23: $285 million

Recipients: As of fiscal year 2021–22, 55 counties operated the Housing Support Program.

Eligible uses: The program offers financial assistance and housing‑related wraparound supportive services, including rental assistance, housing navigation, case management, security deposits, utility payments, moving costs, interim shelter assistance, legal services, and credit repair. The program serves families with children enrolled in CalWORKs who are experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness.

Source: State law and CDSS Website.

The Housing Support Program, which provides financial assistance to families at risk of or experiencing homelessness, is also likely cost‑effective. Table 2 shows our cost‑effectiveness comparison for the Housing Support Program. When we reviewed expenditure and outcome data for 10 counties in the Housing Support Program during the past four fiscal years, we found that those counties spent an average of $12,000 to $22,000 per fiscal year on families that received housing support through the program during this period. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness noted that studies have found that a single chronically homeless person costs taxpayers as much as $30,000 to $50,000 per year. The National Alliance to End Homelessness reported a per‑person cost to taxpayers of $35,578 per year, and in the legislation creating Cal ICH, the Legislature cited a cost of $2,897 per month—or approximately $35,000 annually—in crisis response services for a person experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County. Thus, the Housing Support Program spent less to house or keep housed a family than taxpayers might otherwise expect to pay for an individual to be homeless. During the past four fiscal years, the 10 counties housed nearly 6,000 families. According to California Department of Social Services (CDSS) staff, comparing the cost of the Housing Support Program to the cost of a person’s homelessness is a reasonable method of assessing the program’s cost‑effectiveness.

The data that CDSS collected from the counties related to the Housing Support Program contained sufficient outcome and expenditure information for us to assess cost‑effectiveness. To track program performance and outcomes throughout the year, the department uses targets set by the counties for the number of families they intend to house. It also tracks monthly how many families continue to receive housing. We saw evidence it evaluated and monitored counties’ activities to ensure that the counties adhered to evidence‑based interventions, such as Housing First and Rapid Rehousing best practices, including not making housing contingent on participation in services. Cal ICH could consider CDSS’s example when it creates its own approach to collecting and reporting data on state‑funded homelessness programs, as we previously discuss.

The State Has Not Collected Sufficient Data to Assess the Cost‑Effectiveness of the Other Three Programs We Reviewed

We were unable to fully assess the cost‑effectiveness of three of the programs we reviewed—SRAP, HHAP, and ERF—because of limitations with the data the State has collected. Collectively, these programs received more than $9.4 billion in funding since 2020.

State Rental Assistance Program (SRAP)

Department: California Department of Housing and Community Development

Year Established: 2021

Funding: The federal government provided $4.8 billion to cities and counties in California.

Recipients: 67 cities and counties.

Eligible uses:

- Rental arrears.

- Prospective rent payments.

- Utilities, including arrears and prospective payments.

- Any other expenses related to housing.

- Any additional use authorized by federal law.

Source: Federal and state law, SRAP funding notices.

For example, we could not determine the long‑term cost‑effectiveness of SRAP, which provided financial assistance in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic to help renters facing eviction, because HCD did not collect clear eviction outcome data. According to the online dashboard for the program as of January 2024, SRAP has served more than 370,000 households since its inception, averaging nearly $12,000 per household. HCD staff asserted that SRAP was effective because the program awarded the funding within statutory deadlines and assisted nearly 400,000 households, which staff believe prevented them from becoming homeless. According to state law, it was the Legislature’s intent that the state monitor the usage of funding to ensure that the program stabilized households and prevented evictions; however, the law did not specifically require HCD to track evictions for those receiving SRAP funding. Although it is likely that the rental assistance provided by the program helped some avoid evictions, HCD did not collect eviction data that would enable it to determine whether and how many SRAP beneficiaries might have fallen back into homelessness. The program has now essentially ended because it is no longer accepting applications, and the State is left without an understanding of what percentage of SRAP recipients were unable to avoid eviction, or whether the amounts provided to households were sufficient.

Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program (HHAP)

Department: California Interagency Council on Homelessness

Year Established: 2019

Funding: Round 1–$650 million; Round 2–$300 million; Round 3–$1 billion; Round 4–$1 billion; Round 5–$1 billion

Recipients: CoCs, counties, large cities.

Eligible Uses:

- Rental assistance and rapid re‑housing.

- Operating subsidies in new and existing units.

- Landlord incentives.

- Outreach and coordination.

- Support for homelessness services and housing delivery systems.

- Delivery of permanent housing and innovative housing solutions.

- Prevention and shelter diversion to permanent housing.

- New navigation centers and emergency shelters.

Source: State law and HHAP funding notices.

We were similarly unable to determine the cost‑effectiveness of HHAP Round 1 because of the lack of clear data about outcomes for people who received HHAP‑funded services. The HHAP program provides funding for a variety of services that address multiple aspects of homelessness, including providing interim housing. Cal ICH tracks the spending of HHAP funds by individual eligible use categories. Such tracking shows that, as of December 2022, about half of the HHAP Round 1 funding had been used for emergency shelters and operating subsidies. The amount used for each other eligible use was less than 15 percent.

Determining HHAP’s cost‑effectiveness would require data on the outcomes of each of the HHAP‑funded services and a comparison for each service. Although Cal ICH collects some data when a person exits an HHAP‑funded service, those data are insufficient for evaluating the program’s cost‑effectiveness. For example, CoCs’ exit survey data for people served by HHAP Round 1 funds document people’s intended destinations following their participation in a program. The survey options include permanent housing, a return to homelessness, or an unknown destination. The data we analyzed from four CoCs (Los Angeles, San Diego, San José/Santa Clara, and San Francisco) showed that nearly one‑third of the exits from HHAP Round 1‑funded services left those services for unknown destinations. Because an unknown destination can indicate that the person did not know the destination, that the person refused to answer, that the data was not collected, or that the exit interview was not conducted, we cannot determine whether these people actually exited homelessness. These ambiguous data for nearly one‑third of the exits inhibits any comparison of program costs and outcomes, demonstrating the need for Cal ICH to establish more specific parameters for the data that programs are required to collect and report.

Despite not conducting an analysis of the cost‑effectiveness of HHAP Round 1, the State authorized billions of dollars in funding for four additional rounds. The Legislature made significant changes to the program that began with Round 3, requiring that applicants establish measureable outcome goals, such as reducing the number of people experiencing homelessness and reducing the length of time that people remain homeless. To the extent CoCs establish meaningful outcome goals, the goals should provide better benchmarks against which the State can measure spending and evaluate cost‑effectiveness.

Grantees have until June 2026 to spend the funds from HHAP Rounds 2 and 3, and until June 2027 for Round 4. Consequently, the State will likely be unable to fully assess the effects of that $2.3 billion in funding for years. The HHAP Round 5 application period opened in September 2023; however, the State has not yet awarded $1 billion of funding. The Legislature intends to transfer all grant programs that Cal ICH administers to HCD on or before July 1, 2024, so HCD will likely be the entity that can perform future assessments of HHAP cost‑effectiveness.

Encampment Resolution Funding (ERF)

Department: California Interagency Council on Homelessness

Year Established: 2021

Funding: $750 million ($50 million for round one; $300 million for round two, and $400 million for round 3).

Recipients: Cities, Counties, CoCs.

Round 1 Eligible Uses:

- Direct Services and Housing Options.

- Capacity Building.

- Sustainable Outcomes.

- Administration.

Source: State law, State Budget, and Cal ICH Funding Notice.

We also could not determine the cost‑effectiveness of the ERF program—which transitions people from encampments into safe and stable housing. Cal ICH has not collected complete outcome data for this program, and the expenditure data it has collected may be unreliable. As a condition of its grant agreement, Cal ICH requires that grantees use a template that it created to submit program outcome data about the people the grantees served. Despite this requirement, four of the 10 grantees we reviewed had submitted incomplete or unusable outcome data as of July 2023. Moreover, two of the four grantees did not use the required template. For the template fields for gathering information about people served, including those necessary to determine the number of people permanently housed, multiple grantees entered the words “data not collected” or simply left the fields blank. Cal ICH relies on self‑certified data from grantees and does not attempt to verify the completeness or accuracy of the data submitted. Therefore, the number of people reported as permanently housed through the program is likely incomplete or inaccurate.

Further, Cal ICH does not appear to enforce the reporting requirement. Cal ICH staff explained that the agency started with a small staff. They indicated that as the programs it administered grew in funding and new programs were added, it attempted to hire additional staff to monitor grantee reports. When we asked Cal ICH how it responded to incomplete or unusable outcome data, staff asserted that they contacted grantees to ensure that the outcome data was complete and in the required format. However, when we asked for documentation, staff could provide only emails they sent to three grantees after we brought the issue to Cal ICH’s attention. In these emails, they requested the grantees to use the required template.

State law requires ERF Round 1 grantees to spend 50 percent of grant funds by June 30, 2023, and Cal ICH provided documentation of its efforts to ensure that grantees met the expenditure deadline. It sent multiple emails to grantees reminding them of the deadline, held support meetings with grantees to determine how they would meet the deadline, and provided technical assistance. All 10 grantees we reviewed appear to have met the 50 percent expenditure deadline. However, Cal ICH relies on grantees’ self‑certifying the accuracy of the expenditure amounts.

The State awarded ERF Rounds 2 and 3 to grantees beginning in June 2023, and at the time of our review, the grantees were not yet required to spend the funds. The earliest deadline requires Round 2 grantees to spend half of their allocation by June 30, 2024. As a result, there were not enough data available at the time of our review to assess the cost‑effectiveness of these grants.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following are the recommendations we made as a result of our audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these recommendations can be found in the sections of this report.

Legislature

To promote transparency, accountability, and effective decision‑making related to the State’s efforts to address homelessness, the Legislature should amend state law to require Cal ICH, by March 2025, to mandate reporting by state agencies of costs and outcomes of state homelessness programs. To implement such reporting, the Legislature should require Cal ICH to develop guidance establishing specifics on uniformity of data to be collected and how it is to be presented. The Legislature should require Cal ICH to annually compile and report this cost and outcome information publicly beginning in September 2025 and should provide resources for this effort, as necessary.

Cal ICH

To ensure that its 2024 update to its action plan aligns with the statutory goals that the Legislature has established, Cal ICH should clearly identify in that update the statutory goal or goals that each of the action plan’s objectives addresses.

To promote transparency, accountability, and effective decision‑making related to the State’s efforts to address homelessness, Cal ICH should request that state agencies responsible for administering state‑funded homelessness programs provide spending‑ and outcome‑related information for people entering, experiencing, and exiting homelessness. By March 2025, Cal ICH should develop and publish on its website a scorecard—or similar instrument—on the homelessness programs that would enable the Legislature and other policymakers to better understand each program’s specific costs and outcomes. Cal ICH should determine and request from the Legislature any necessary resources required for this effort.

To ensure that the State has consistent, accurate, and comparable data for all state‑funded homelessness programs, by March 2025, Cal ICH should work with CoCs to implement standardized data requirements that programs must follow when entering information into HMIS. The requirements should establish expectations defining CoCs’ responsibilities for ensuring data accuracy and reliability.

OTHER AREAS WE REVIEWED

To address the audit objectives approved by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee), we also reviewed housing placements and the sharing of homelessness data.

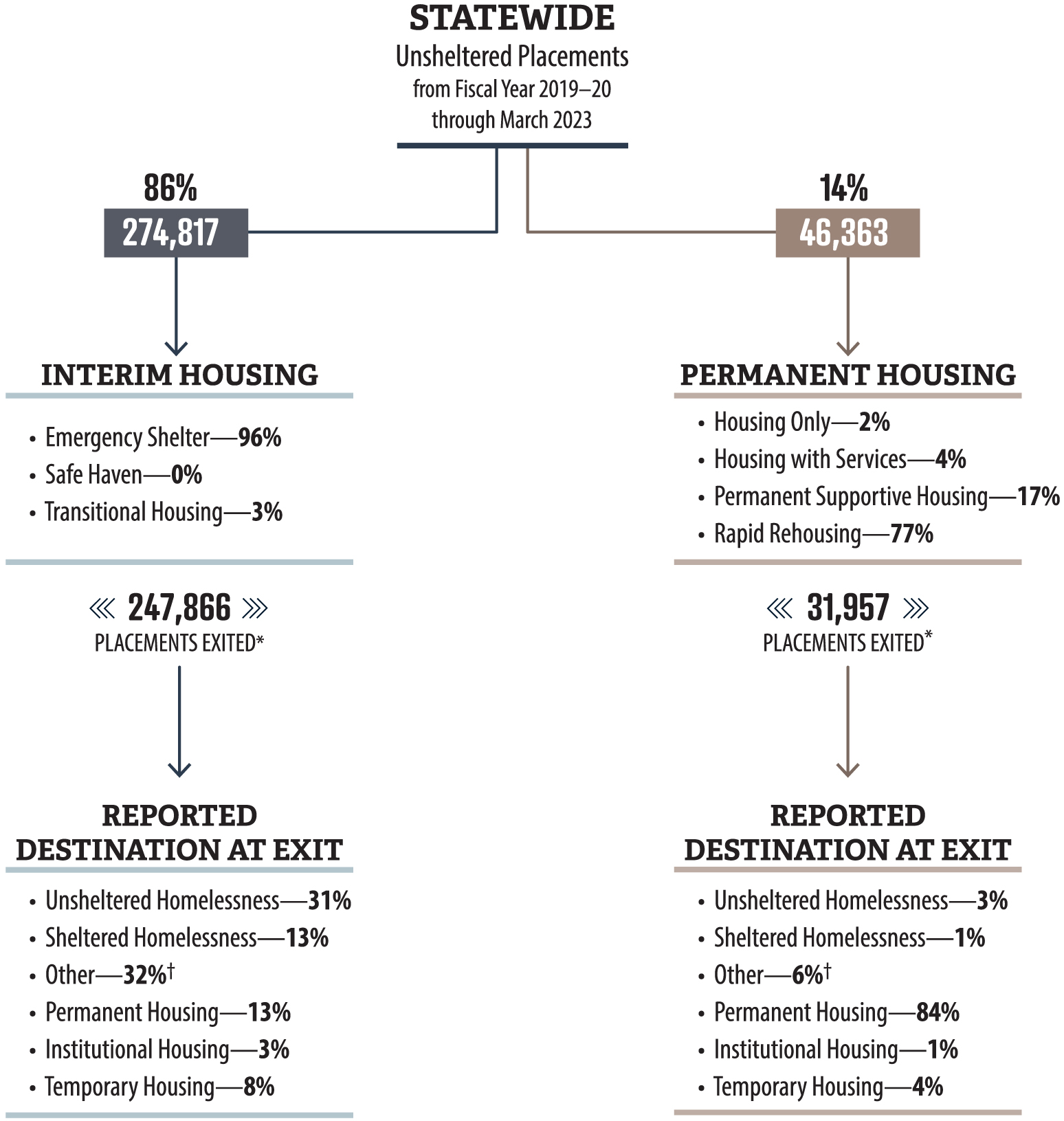

Most Placements of Unsheltered People Into Interim Housing Do Not End Up in Permanent Housing

The vast majority of housing placements for Californians experiencing unsheltered homelessness involve interim housing. The text box describes the types of interim and the types of permanent housing. Interim housing is a critical service that protects people from many of the impacts of unsheltered homelessness, including health and safety risks. Using information in the state data system, we identified placements of unsheltered people into housing from July 2019 through March 2023. As Figure 6 shows, 86 percent of placements statewide moved people into interim housing rather than into permanent housing. Appendix B shows additional details about placements. The placement of individuals into interim housing likely occurs in part because of the lack of available permanent housing in the State.

Types of Interim Housing

Emergency Shelter: Any facility with the primary purpose of providing a temporary shelter for the homeless in general or for specific populations of the homeless and which does not require occupants to sign leases or occupancy agreements.

Transitional Housing: Housing that facilitates the movement of homeless individuals and families into permanent housing within 24 months or longer, as determined necessary.

Safe Haven: Supportive housing that serves hard‑to‑reach homeless persons with severe mental illness who came from the streets and have been unwilling or unable to participate in supportive services.

Types of Permanent Housing

Rapid Rehousing: Housing relocation and stabilization services and short‑term and medium‑term rental assistance as necessary to help a homeless individual or family move as quickly as possible into permanent housing and achieve stability in that housing.

Permanent Supportive Housing: Permanent housing in which supportive services are provided to assist homeless persons with a disability to live independently.

Other Permanent Housing: This includes permanent housing with supportive services for persons experiencing homelessness who do not have a disability and long‑term housing without supportive services.

Source: Federal Law.

Nonetheless, the final phase of homelessness—exiting homelessness—should ideally culminate with individuals living in permanent housing. People experiencing unsheltered homelessness who were placed into interim housing had worse outcomes when exiting the placement than those placed into permanent housing. Specifically, the data show that only 13 percent of the exits from interim housing placements reported individuals moving into permanent housing. In contrast, the data show that 84 percent of exits from permanent housing placements reported individuals moving into other permanent housing.7 The data further show that 44 percent of the exits from interim housing reported individuals returning to homelessness, as opposed to 4 percent of exits from permanent housing placements.

Figure 6

Unsheltered Placements and Outcomes

Source: Homeless Data Integration System.

Note: Rounding of numbers may prevent percentages from totaling 100.

* Some placements of individuals showed that the person had not yet exited the program and was still enrolled and receiving shelter or housing services as of the date we obtained the data; therefore, the number of placements is higher than the number of those who exited the program.

† Category Other can include the following: worker unable to determine, client doesn’t know, client prefers not to answer, data not collected, or other.

Figure 6 description:

Figure 6 is a tree diagram that depicts the total placements statewide of individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness into interim and/or permanent housing types from the fiscal year 2019-20 through March 2023. At the top of the figure, the diagram bifurcates into two main branches, one branch for interim housing and the other branch for permanent housing. Both of these branches then list and describe the percentages of people who were placed in their specific types of housing. Both the interim and permanent branches then continue to how many total individuals exited the interim or permanent housing placement or placements they received. Finally, the branches culminate in listing the types of destinations individuals could have exited to and the percentages for each exit destination. For example of the 247,866 placements that exited interim housing, 31% of those placements returned to experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Of the 31,957 placements that exited a type of permanent housing, 3% returned to experiencing unsheltered homelessness. The text at the bottom of the figure provides more context on the data presented in the tree diagram.

Permanent housing outcomes for people in federally‑funded programs are shown in the text box at right and generally align with the outcomes of programs that were not federally‑funded. However, we were unable to separate out the permanent housing outcomes for the subcategory of state‑funded programs from the overall permanent housing outcomes because of inconsistent data. Each federal program has a code that a service provider selects when entering information about projects into HMIS. Using this code, we could determine the outcomes for federally funded programs. Until July 2023, state programs did not have similar program codes; instead, the service provider who entered the data typed the program name into a text field. This practice led to inconsistent entries for state programs, because each service provider might type something different for the same program. For example, the HHAP program has been entered as “CA‑HCFC‑HHAP 1,” ”HHAP,” ”State HHAP,” “County HHAP‑1,” as well as other variations. These inconsistencies make the data unreliable for identifying programs to determine permanent housing outcomes.

Outcomes for People Exiting Placements in Permanent Housing Funded by Federal Programs

STATEWIDE

- 82 percent left to some type of permanent housing

- 4 percent left to homelessness

Source: State data system data for placements from July 2019 through March 2023.

Since July 2023, providers that receive state funding are required to provide state funding information according to Cal ICH instructions that include state‑specific codes. Thus, going forward, the state data should have more complete funding source information. This will allow the State to better determine the outcomes associated with state programs such as HHAP.

Cal ICH Has Recently Begun Facilitating the Sharing of Certain Data Related to Homelessness Programs

Several federal and state laws and regulations may impede the ability of the State or local jurisdictions to accurately assess and track certain information about people who are experiencing homelessness. The text box lists some of these laws. Generally, the laws and regulations protect the confidentiality of personal information. However, in doing so, they also could limit the collecting and sharing of data to evaluate homelessness efforts and may also affect access to supportive services.

Federal and state laws limit the data that can be shared without consent.

FEDERAL

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act: Applies to health plans and certain health care providers. Some protected health information data may be disclosed without consent if the data will only be used for limited purposes.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act: Applies to educational agencies or institutions that receive federal funding. Personally identifiable information from educational records can be disclosed without consent as long as it is used for purposes related to that person’s education.

Violence Against Women Act: Applies to covered housing providers who serve victims of domestic or dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking. The providers cannot share a victim’s information without consent of the victim.

HMIS Standards: Client consent is required to share data, but not to enter data into HMIS.

Substance Abuse Records: Some records can be disclosed without consent in case of medical emergency, research, or audit purposes. Consent form must outline exactly what can be disclosed; can be revoked at any time.

STATE

Confidentiality of Medical Information Act: Individual must consent to disclosure of medical information by a healthcare plan or provider unless there is a court order, search warrant, death investigation, or need for diagnosis or treatment.

Information Privacy Act of 1977: Individual must consent to disclosure of personal information by a State agency unless there is a legal requirement or a medical necessity.

Juvenile Case Records: Files may only be accessed by someone who is related to, works with, or represents the child.

Source: Federal and state law.

The main source of data about people experiencing homelessness is local HMISs. As we previously discuss, the CoCs are responsible for collecting data in an HMIS from entities that provide services to people experiencing homelessness. When doing so, they must ensure compliance with federal privacy and security standards. These standards allow for certain uses of people’s protected personal information (protected information), including for the provision and coordination of services, service payment and reimbursement, administrative functions such as audits, and the removal of duplicate data. CoCs use signed consent forms to allow them to share the data provided by people who access homelessness services.

Although local governments generally have access to the data they input into their HMIS, they might not have access to personal information added by other entities. However, effective January 2018, state law began allowing agencies that provide services to people experiencing homelessness, including cities, to establish multidisciplinary teams to share information that is confidential under state law with one another under certain circumstances. Each county that establishes a multidisciplinary team must have protocols for sharing data within these teams. Further, they must provide these protocols to CDSS, which is a member agency of Cal ICH. However, we recognize that federal law might still present barriers to sharing data.

In addition, Cal ICH has begun to facilitate some data‑sharing with CoCs by making available a dashboard with anonymized aggregate data—such as the number of people accessing particular services—that it receives from each of the CoCs. Doing so may enable local jurisdictions to analyze the data and to better identify and understand the services that are being provided and outcomes of those services.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code section 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

April 9, 2024

Staff:

Nicholas Kolitsos, CPA, Principal Auditor

Jordan Wright, CFE, Principal Auditor

Chris Paparian, Senior Auditor

Nicole Menas

Eduardo Moncada

Data Analytics:

Ryan Coe, MBA, CISA

Brandon Clift, CPA

Legal Counsel:

Joe Porche

APPENDICES

Appendix A

Statewide Homelessness Assessment: Programs and Funding

Fiscal Years 2018–19 Through 2020–21

Cal ICH published a Statewide Homelessness Assessment (homelessness assessment) in 2023 for the Legislature. The Legislature’s intent in requesting the assessment was to obtain trustworthy information to connect funding allocated to prevent and end homelessness with established sheltering and housing resources and to provide state agencies with accurate information for more accurate forecasting to target future investments. The homelessness assessment covered fiscal years 2018–19 through 2020–21. Table A shows the list of state programs and funding that Cal ICH identified in the homelessness assessment. Because the State has awarded a significant amount of additional funding and created new homelessness programs, we believe that the State’s policymakers and the public need regular updates of this information to evaluate the effectiveness of state spending to prevent and end homelessness.

Appendix B

Placements Into Interim and Permanent Housing

From Fiscal Year 2019–20 through March 2023

We used the state data system to identify the number of times a reporting entity placed people into different types of housing. Table B shows the number of placements into both permanent and interim housing. Statewide, the table shows how many placements of people were in each category of housing, with the majority placed into interim housing—emergency shelter, in particular.

Appendix C

Scope and Methodology

The Audit Committee directed the California State Auditor to conduct an audit to assess the effectiveness of the State’s spending on homelessness. Specifically, the Audit Committee asked us to review the State’s structure and efforts for funding and addressing homelessness and the cost‑effectiveness of a selection of five state homelessness programs. Table C lists the objectives that the Audit Committee approved and the methods we used to address them. The Audit Committee also requested that we review the outcomes that the city of San José and another city achieved with federal, state, and local homelessness funding. The results of our review of these two cities is included in a separate report (2023‑102.2). Unless otherwise stated in the table or elsewhere in the report, statements and conclusions about items selected for review should not be projected to the population.

Assessment of Data Reliability