2023-048 Cannabis Business Licensing

Inadequate Oversight and Inappropriate Expenditures Weaken the Local Jurisdiction Assistance Grant Program

Published: August 29, 2024Report Number: 2023-048

August 29, 2024

2023‑048

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

State law requires my office to conduct a performance audit of the local jurisdictions that received funds as part of the Local Jurisdiction Assistance Grant Program (Grant Program). State law also requires the Department of Cannabis Control (DCC) to administer the Grant Program, which we also audited. In general, we determined that DCC’s inadequate oversight and the local jurisdictions’ inappropriate expenditures during the first year of the Grant Program have weakened the program’s ability to achieve its purpose, which is to assist certain local jurisdictions needing assistance in transitioning cannabis businesses that hold provisional licenses to obtain annual state licenses.

Although the 17 local jurisdictions that received grant funds (grantees) were able to transition about 530 provisional licenses to annual state licenses, the grantees still had more than 4,600 provisional licenses that needed to transition as of January 1, 2023. Several factors contributed to the grantees’ slow progress, including their limited spending of grant funds in the program’s first year and DCC’s continued issuance of provisional licenses through September 2022. Moreover, DCC has not tracked key steps in its licensing process that would have allowed it to identify and address whether delays resulted from applicants, local jurisdictions, or its own processes.

Although DCC took steps to improve its administration of the Grant Program after we communicated concerns to its leadership in July 2023, some shortcomings in DCC’s grant management practices remain unresolved. For example, DCC cannot accurately measure whether the 17 grantees are on track to accomplish the purpose of the Grant Program because DCC did not ensure that they provided clear goals or measurable benchmarks. DCC also did not obtain documents from grantees that would have revealed problems with their expenditures. As a result, two grantees reported to DCC $26,000 in costs that we questioned because they could not substantiate that all of their grant fund spending was appropriate.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CEQA | California Environmental Quality Act |

| DCC | Department of Cannabis Control |

| GFOA | Government Finance Officers Association |

| OGM | Office of Grant Management |

Summary

Results in Brief

California voters in November 2016 legalized the nonmedical personal use of cannabis for adults 21 years of age or older.1 Under California law, cannabis businesses must generally obtain an annual state license to operate legally. The State initially issued provisional licenses to encourage cannabis businesses to transition into the newly state-regulated market. However, most provisional licenses will no longer be effective after January 2026.2 To continue operating legally under California law after that date, provisional license holders must obtain an annual state license. The 2021 Budget Act appropriated $100 million for the Local Jurisdiction Assistance Grant Program (Grant Program) to assist 17 selected local jurisdictions (grantees) in helping provisional license holders that need the greatest assistance in obtaining an annual state license. Grantees must expend or encumber the grant funds before June 30, 2025. The Department of Cannabis Control (DCC) administers the Grant Program and issues provisional and annual state licenses.

DCC Did Not Appropriately Oversee the Grant Program

DCC’s management of the Grant Program did not follow certain best practices in grant administration. For example, it did not ensure that grantees provide measurable benchmarks for each goal in their grant agreements. As a result, DCC could not measure grantees’ progress toward their goals, and in four instances, the grant agreements that DCC approved did not include goals against which to measure progress. DCC also did not establish sufficient monitoring of grantees’ expenditures or request documentation for those expenditures. Consequently, DCC has not obtained documentation that would have revealed problems with the grantees’ expenditures, including unallowable and underreported costs.

DCC also did not establish benchmarks for the Grant Program itself, to accurately measure whether the Grant Program is on track to accomplish its purpose, and DCC did not initially establish a spending plan for its administrative funds. Consequently, DCC has spent just $350,000 of the $5 million it has to administer the program, has understaffed the program with staff who are underqualified to manage a program of this complexity, and has not responded to grantees’ amendment requests in a timely manner. After we informed DCC through a July 2023 management letter about its staffs’ inexperience and the other problems that we identified in its grant management and use of administrative funds, DCC took immediate action to address some of these issues. However, as of May 2024, other issues with DCC’s grant management practices remain unresolved.

Some Grantees Did Not Manage Their Grant Funds Properly

We determined that some grantees’ processes for managing the awarded funds did not align with best practices. We found that not all grantees adequately tracked their expenditures and documented whether staff time charged to the Grant Program was spent on tasks related to the program. By not adequately tracking expenditures, grantees hindered DCC’s ability to track their spending. We also identified $26,000 in costs we questioned because two grantees could not substantiate that the spending was appropriate.

The Grant Program May Not Achieve Its Goals, and DCC Cannot Determine the Causes of Delays in License Processing

As of January 1, 2023—the end of the Grant Program’s first year—more than 4,600 provisional license holders in the 17 grantees’ jurisdictions still needed to obtain annual state licenses. During the first year of the Grant Program, the average rate at which provisional license holders in the grantees’ jurisdictions were obtaining annual state licenses did not increase from the prior year’s rate. We selected six grantees for further review and identified several factors that contributed to the grantees’ slow progress in helping provisional license holders transition to annual state licenses. These factors include limited spending of grant funds in the first year and, in the case of one grantee, delays in changing the application process by which cannabis businesses could transition from provisional licenses to annual state licenses. In addition, despite experiencing license processing times that average two years, DCC did not track key steps in its licensing process. Such tracking would have allowed DCC to analyze those steps that contribute most to delays and identify solutions to mitigate delays in its process. The lack of data and documentation on when steps in the application process are completed prevented us from analyzing the potential causes for delays in processing times.

Agency Comments

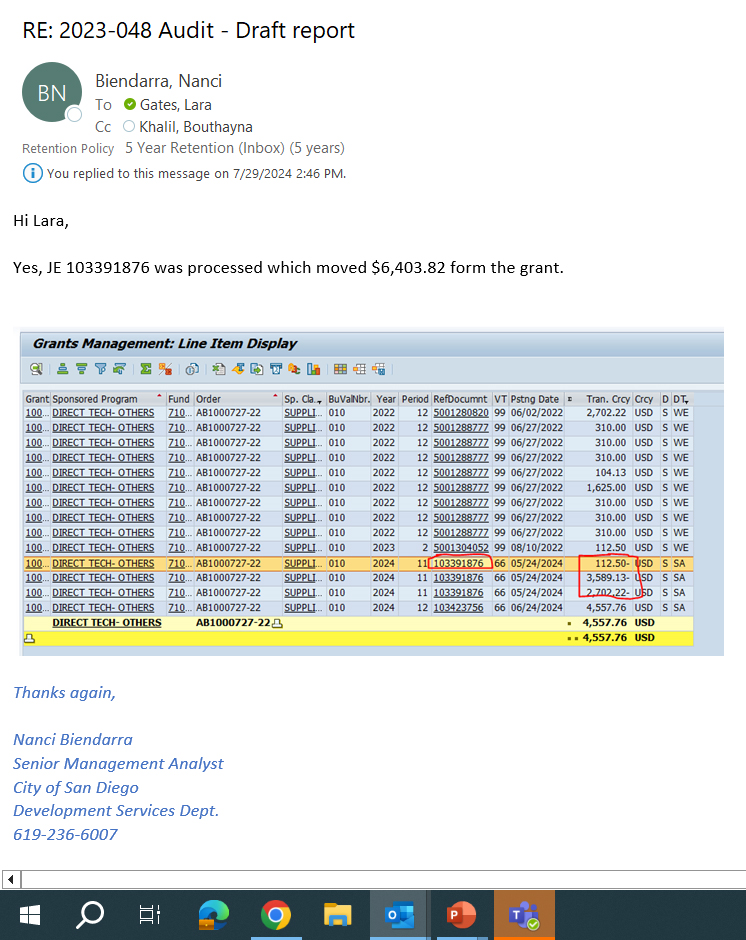

DCC agreed or partially agreed with most of the recommendations we made and stated concerns or offered additional perspective on several of our conclusions. However, DCC disagreed with our recommendation to give grantees more time to spend grant funds because it believes doing so would inhibit its ability to close out the Grant Program in a timely manner. Of the four local jurisdictions to which we made recommendations, the city of Long Beach agreed with our recommendation and the city of San Diego offered the perspective that it had repaid the $6,000 in misspent funds that we identified. The city of Commerce and the county of Humbolt chose not to submit a response.

Introduction

Background

In November 2016, California legalized the nonmedical personal use of marijuana (cannabis) for adults 21 years of age or older.3 During the 2022 calendar year, taxable sales of cannabis in California totaled $5.4 billion. Under California law, cannabis businesses must generally comply with local cannabis permitting processes and obtain a license from the State to operate legally. The State initially issued provisional licenses to encourage cannabis businesses to transition into the newly regulated market. Provisional licenses are only valid for up to 12 months, but DCC may renew a provisional license, subject to certain requirements, until DCC issues or denies an annual state license. As a condition for holding a provisional license, the licensee must actively apply for and pursue an annual state license.

The State continues to issue provisional licenses to a subset of cannabis businesses—local retail equity applicants—but no longer issues provisional licenses otherwise. To obtain a provisional license, applicants must generally meet certain requirements. First, they must comply with any local cannabis permitting processes in their respective jurisdictions or submit evidence that compliance is underway. Because state law grants local control to individual jurisdictions, the jurisdictions generally may choose the extent of their restrictions: for example, they may decide not to allow any type of cannabis businesses to operate, they may issue permits for only certain types of cannabis businesses, or they may set limits on the number of cannabis businesses that may operate within their boundaries.4 Local jurisdictions also assess and set fees for their permitting processes, annually renew permits, and may perform on-site inspections of cannabis businesses.

In addition to satisfying local jurisdiction requirements, applicants must pay DCC an application fee. To meet other requirements, such as compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), applicants for a provisional license need only provide evidence that their efforts to meet DCC’s requirements is underway. Thus, the provisional licensing process expedited the ability of applicants to operate legally in California as cannabis businesses.

However, most provisional licenses will no longer be effective after January 1, 2026. To continue operating legally under California law after this date, applicants must obtain an annual state license, which requires them to, among other things, finish completing any requirements for annual licensure that were underway at the time they obtained their provisional license. Until applicants obtain an annual state license, they may not be in full compliance with all requirements, including requirements related to environmental protection.

Three state entities each oversaw particular types of cannabis business licensure until the Department of Cannabis Control (DCC) was established in July 2021, as the text box details. These entities’ responsibilities were consolidated under DCC, which now issues annual state licenses for all cannabis businesses, including cultivation, retail, and manufacturing businesses. However, DCC stopped issuing most provisional licenses as of October 2022. DCC may continue issuing provisional licenses to local equity applicants for retail business until January 1, 2031.

Three State Agencies Regulated Cannabis Businesses Following Legalization of Nonmedical Marijuana Under California Law Until DCC Assumed These Responsibilities in July 2021

California Department of Food and Agriculture

- Cannabis Cultivation

California Department of Public Health

- Cannabis Manufacturing

Bureau of Cannabis Control*

- Cannabis Retailers

- Cannabis Distributors

- Cannabis Microbusinesses

- Cannabis Testing Laboratories

- Cannabis Event Organizers

Source: State law and California State Association of Counties’ Local Government Reference Guide to Proposition 64.

* Formerly known as the Bureau of Medical Cannabis Regulation and the Bureau of Medical Marijuana Regulation.

A local equity applicant is an individual applying for a commercial cannabis license who participates in a jurisdiction’s local equity program. These programs focus on the inclusion and support of individuals and communities in the State’s cannabis industry who are linked to populations or neighborhoods that have experienced negative or disproportionate impact from cannabis criminalization. According to DCC, cannabis business owners face many challenges to getting started, including difficulties gaining access to capital and obtaining technical support, which can be even harder for individuals who were affected by cannabis criminalization. Equity programs as described in state law may include such services as technical assistance for small businesses, fee waivers, and assistance in securing capital investments.

California Environmental Quality Act

State law allows an applicant to obtain a provisional license without completing certain requirements necessary for annual state licensure. One such requirement pertains to compliance with CEQA. The purposes of CEQA are, among other things, to inform governmental decision-makers and the public about potentially substantial environmental effects of proposed activities and to prevent significant, avoidable damage to the environment. CEQA is relevant to licensing because cannabis businesses may harm environmental quality. For example, cannabis cultivation can result in fertilizer runoff leaching into watersheds, with negative consequences for wildlife. All types of cannabis businesses, including retail and manufacturing businesses, must comply with CEQA or show that their business is exempt from the requirements. To obtain a provisional license, and then to renew a provisional license, an applicant must provide evidence to DCC that the business is in the process of complying with CEQA, if it has not yet done so. To then meet annual state licensing requirements, the applicant must complete the CEQA process and provide proof that the business is either exempt from or has complied with CEQA.

Establishing the Local Jurisdiction Assistance Grant Program

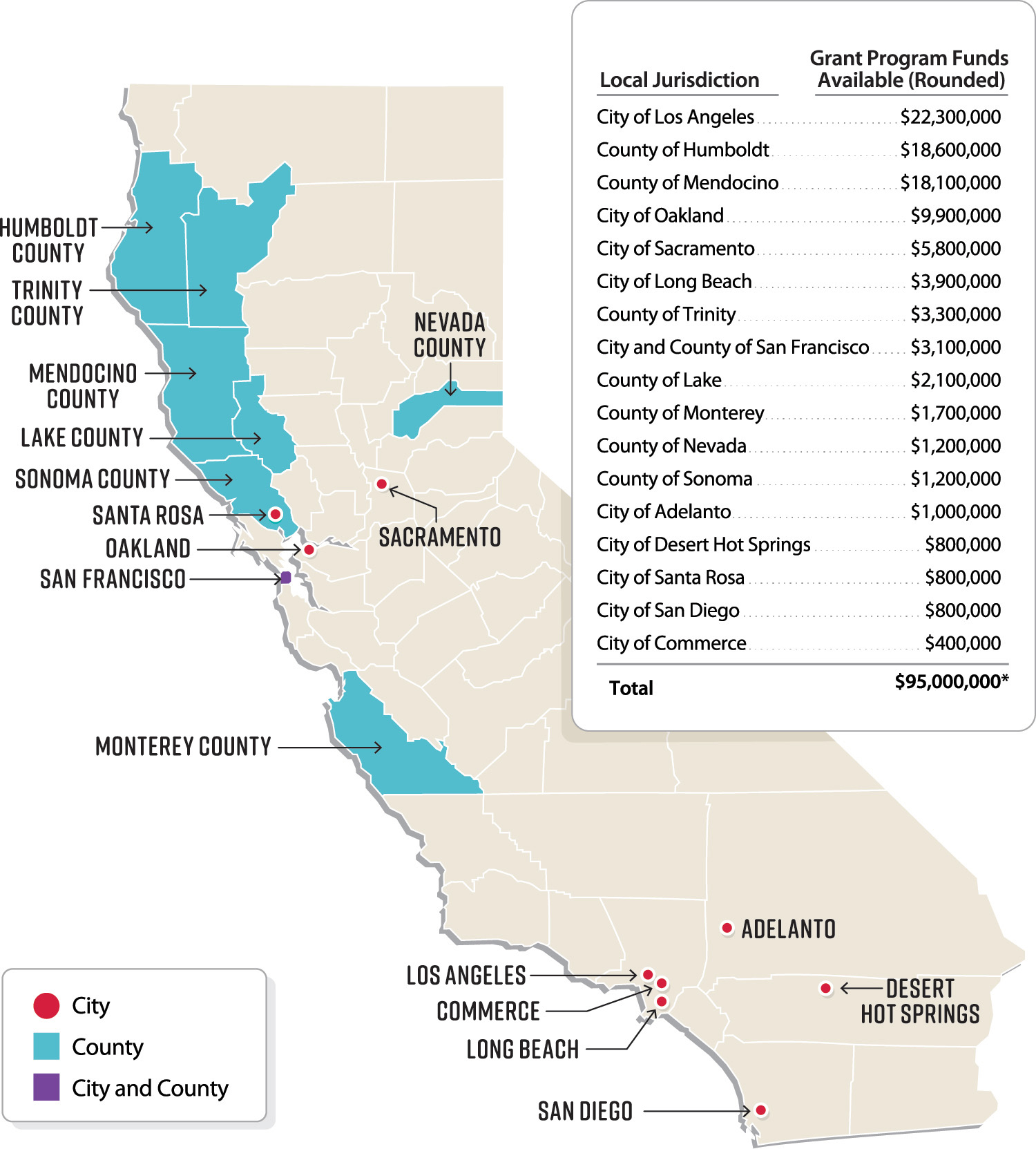

The Budget Act of 2021 appropriated $100 million to DCC for the Local Jurisdiction Assistance Grant Program (Grant Program). The Grant Program was created in July 2021—the same month that DCC was established as an agency—to assist 17 selected local government jurisdictions of cities and counties (grantees) in helping commercial cannabis license holders who need the greatest assistance to transition from a provisional license to an annual state license. Figure 1 identifies these grantees and the maximum amounts the Legislature designated for each. According to the Budget Act, these 17 grantees had in their jurisdictions significant numbers of provisional licensees as well as provisional license holders with greater CEQA compliance requirements. The Budget Act established certain allowable uses for the grant funds, such as the preparation of environmental documents to achieve CEQA compliance, and other uses that further the intent of the Grant Program, which is to assist provisional license holders’ transition to annual state licenses issued by DCC.

The Budget Act also designated $5 million of the $100 million for DCC to administer the Grant Program, and it established a deadline of June 30, 2025, for the grantees to expend or encumber the grant funds. All funds disbursed to the grantees that are not spent by that deadline will revert to the State’s General Fund. Finally, the Budget Act required the California State Auditor, beginning in 2023, to conduct three annual performance audits of the grantees receiving funds from the Grant Program.

Figure 1

Seventeen Local Jurisdictions Were Eligible to Receive Grant Funding

Source: State law.

* The total does not include the $5 million appropriated to DCC for administering the Grant Program.

The map of California shows counties highlighted if they received grant program funds and cities are represented with red dots where they are located. Many of the highlighted counties are located in the northern, coastal area of the State, including Humboldt County, Trinity County, Mendocino County, Lake County, Sonoma County, and Monterey County.

Local jurisdictions had available to them grant funds in the following amounts: city of Los Angeles, $22.3 million; county of Humboldt, $18.6 million; county of Mendocino, $18.1 million; city of Oakland, $9.9 million; city of Sacramento, $5.8 million; city of Long Beach, $3.9 million; county of Trinity, $3.3 million; city and county of San Francisco, $3.1 million; county of Lake, $2.1 million; county of Monterey, $1.7 million; county of Nevada, $1.2 million; county of Sonoma, $1.2 million; city of Adelanto, $1 million; city of Desert Hot Springs, $800,000; city of Santa Rosa, $800,000; city of San Diego, $800,000; city of Commerce, $400,000. Total grant program funds available, $95 million. We note at the bottom of the graphic that the total amount does not include the $5 million appropriated to the Department of Cannabis Control for administering the Grant Program.

The work we conducted for this audit report generally pertains to the first year of the Grant Program, from January 2022 through December 2022. In addition to reviewing grant-related expenditures at all 17 grantees, we selected six of these grantees for further review: the counties of Humboldt, Lake, and Trinity, and the cities of Commerce, Los Angeles, and Santa Rosa. We based this selection in part on the amount of grant funds these grantees reported spending and the percentage of provisional license holders in their jurisdictions to whom DCC stated it had issued annual state licenses.

As part of its process for awarding the grant funds, DCC required each of the grantees to submit an application containing an annual plan that described how the jurisdiction intended to use those funds to help provisional license holders’ transition to annual state licenses. In its grant guidelines and application instructions, DCC stated that its application review would include assessing the jurisdiction’s proposed budget and the jurisdiction’s objectives and goals for helping provisional license holders obtain annual state licenses. The annual plan that a jurisdiction submitted as part of its grant application then became part of the scope of work for the grant agreement.

By January 2022, DCC had approved agreements with all of the grantees, and it began disbursing grant funds in February 2022. DCC had disbursed 80 percent of the amount awarded to each grantee by the end of April 2022. It withheld the remaining 20 percent until grantees had substantially met the goals and intended outcomes of their annual plans. As part of the initial agreements, DCC also required grantees to provide biannual progress reports. DCC’s grant guidelines stated that in these reports, grantees must be able to demonstrate that grant funds were spent for eligible uses and were consistent with the activities detailed in their applications. DCC required grantees to submit the first biannual report in August 2022 and the second in February 2023.

DCC’s Office of Grants Management (OGM) administers the Grant Program. According to its operations branch chief, OGM generally had two staff members during the period we reviewed, a grants manager and a grants management analyst. OGM also administered other grants during this time, including the Local Jurisdiction Retail Access Grant, which provides funding to local governments to develop and implement cannabis retail licensing programs.

July 2023 Management Letter From the State Auditor to DCC

The Grant Program has a relatively short lifespan of four years. Because of the severity and pervasiveness of the issues we identified in DCC’s management of the Grant Program, we sent a letter to DCC’s director in July 2023 (management letter) describing our concerns in advance of our completion of this audit, so that DCC could begin taking corrective action. The text box lists the concerns we described in the letter. We discuss these issues and DCC’s actions in response in more detail. However, not all of DCC’s actions have fully addressed our concerns, and we subsequently identified some additional concerns about other aspects of DCC’s management of the Grant Program.

Concerns Described in Management Letter to DCC

- Approval of questionable grantee spending plans.

- Advances of grant funds to grantees not prepared to receive them.

- Lack of scrutiny over grantee spending and progress.

- Misspending of administrative funds.

- Lack of staff with necessary expertise to oversee the Grant Program.

Source: July 2023 Management Letter to DCC.

Chapter 1

DCC Did Not Appropriately Oversee the Grant Program

- DCC has not effectively overseen the Grant Program or effectively used its administrative funds, causing delays in some grantees’ spending of grant funds and creating risks that the Grant Program will not accomplish its primary purpose.

- DCC’s oversight lapses include approving grantees’ uses of the funds unrelated to the program’s purpose; not following grant management best practices in multiple areas, including in the way DCC disbursed funds and monitored expenditures; and not approving some grant amendment requests in a timely manner.

- These lapses result from DCC not employing sufficient staff to manage the Grant Program, and the staff that it did hire or transfer to this program did not possess prior experience managing a grant program.

One Grant Agreement DCC Approved Included Plans That Did Not Align With the Grant Program’s Purpose

The Grant Program’s purpose is to support local jurisdictions in aiding provisional license holders meet those requirements that are necessary to attain an annual state license. However, DCC approved an $18 million grant agreement—the second largest grant in the entire program—for the county of Humboldt that allows the jurisdiction to use as much as $15 million of the funds for purposes unrelated to the Grant Program’s intent. DCC’s review of this grant agreement merited additional attention, considering that the county’s grant was nearly 20 percent of the Grant Program’s total grant funds.

The county of Humboldt proposed using up to $15 million to provide sub-grants to commercial cannabis license holders, including both provisional license holders and those that had already obtained annual state licenses. The county intended these sub‑grants to help offset the costs license holders incurred in reducing their businesses’ environmental impact. For example, the businesses could use the funds to transition from using gas-powered generators to using renewable energy sources. Although provisional licensees were the priority for these sub-grants, the county’s director of planning and building acknowledged that the county’s use of grant funds was never intended for the transition of provisional licenses to annual state licenses. He explained that most of Humboldt’s cannabis businesses were making progress toward obtaining annual state licenses and that the county’s goal for using these funds was to ensure environmental protection and to address roadblocks to obtaining local permits.

Although that goal may benefit the county of Humboldt and its residents, providing sub-grants to cannabis businesses that have already obtained an annual state license does not align with the purpose for which the Legislature appropriated these funds. In February 2023, the county Board of Supervisors passed a resolution that approved 259 applications for sub-grants that totaled more than $12 million. Documentation that the county presented to its Board of Supervisors showed that about 50 of those applications—totaling about $3 million—were from annual state license holders, and the remaining applications were from provisional license holders. As the oversight agency for the Grant Program, DCC was responsible for assessing the county’s grant application and the purpose for which it intended to use the funds. When we raised this issue with DCC, its staff responded that DCC understood the county’s sub‑grants to commercial cannabis license holders were intended to aid license holders that held provisional permits to meet the county’s conditions for approval. However, the county’s grant agreement clearly states that some applicants for these sub-grants already held an annual state license, and the Grant Program funds were to support local jurisdictions in aiding provisional license holders with meeting the requirements to attain an annual state license.

DCC’s Management of the Grant Program Has Not Aligned With Best Practices

Several different entities, including the Federal Office of Management and Budget and the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA)—an organization whose mission is to advance excellence in public finance—have established guidance that DCC could have used to inform its implementation and oversight of the Grant Program. As Table 1 illustrates, DCC did not follow certain grant management best practices, such as limiting advance payments to the minimum amounts grantees needed and timing those payments to the grantees’ actual, immediate cash requirements.

By not following established guidance and best practices, DCC has limited its ability to effectively administer the Grant Program and measure grantees’ progress in assisting provisional license holders with obtaining annual state licenses. After we brought the issues in Table 1 to DCC’s attention in July 2023, DCC stated that it intended to address many of them. For example, DCC developed an assessment questionnaire to use for future grant programs to determine applicants’ readiness to manage grant funds. DCC said that if applicants score poorly on the assessment, it would institute additional safeguards in the grant agreement or require applicants to correct deficiencies. In addition, DCC’s director provided context on why DCC chose to disburse 80 percent of the funds up front, stating DCC’s belief that the Legislature intended it to promptly distribute the grant funds to allow local jurisdictions to meet the deadlines in state law. We acknowledge that the Legislature did use this language in a trailer bill to the Budget Act of 2021. DCC’s chief deputy director added that grantees planned to use the funds for activities that would require lots of lead time, such as hiring staff or contractors, and thus DCC decided that the jurisdictions would need the funds quickly. Although we appreciate that DCC may have acted with the best interest of the grantees in mind, immediately advancing them nearly all of the grant funds increased the risk that the grantees would use the funds inappropriately.

DCC did not initially issue guidance to the grantees on how to apply for the remaining 20 percent of the grant funds. The grant guidelines from October 2021 state that DCC would distribute the remaining 20 percent of the grant funds awarded to grantees, an amount totaling approximately $19 million, after grantees had substantially met the goals and intended outcomes in their annual plans. However, DCC did not define this term in the guidelines, leaving the grantees without a metric for demonstrating that they have met the benchmark and leaving DCC without a metric for evaluating whether grantees have met the benchmark.

DCC’s former grants manager explained that DCC would begin considering the issue after the August 2023 biannual reports were submitted.5 In November 2023, the operations branch chief explained that DCC was preparing instructions for grantees on how to submit a request for the remaining funds. DCC sent those instructions to grantees in April 2024.

DCC has not yet addressed all of the issues we identified. Specifically, DCC still needs to improve its monitoring of grantees’ expenditures. DCC’s decision to advance 80 percent of the grant funds to grantees increased the importance of its monitoring of that spending. However, the former grants manager stated that because of insufficient staffing, she did not verify grantees’ reported expenditures, nor did she request additional documentation to ensure that grantees spent the funds as they reported in their biannual reports. Instead, she used the grantees’ biannual reports to assess whether they were spending funds appropriately. However, she did not articulate the criteria or measures she used to do so.

DCC’s chief deputy director said DCC intended to leverage our office’s statutorily required audit to support its oversight. She also stated that the OGM requested documentation to investigate certain expenditures. Nevertheless, DCC is responsible for administering the Grant Program, and state law establishes our role as auditing the performance of the program—not performing administrative functions, such as overseeing the grantees and their expenditures.

Because DCC has not conducted sufficient monitoring, including verifying that grantees have used grant funds for the purpose the Legislature appropriated those funds, DCC had not identified problems with grantee spending that our audit identified. For example, we determined that the city of San Diego inappropriately spent $6,000 during 2022 to develop its equity program. The use of these funds that the deputy director of San Diego’s Cannabis Business Division described, which involved establishing and promoting a new local equity program in the city, did not align with the requirement in state law that funds could be used for an existing equity program. When we described this issue to DCC’s chief deputy director, she agreed that a grantee could not use the grant funds to develop an equity program. However, DCC did not identify these expenditures as potentially inappropriate even after San Diego reported them in its February 2023 biannual report.

During the course of our audit work, several of the grantees stated that their use of the funds did not focus solely on assisting provisional license holders. In some cases, grantees were instead using the funds for conducting work related to new applicants. For example, the city of Santa Rosa’s senior planner explained that when a new local commercial cannabis business submits an application, she charges her time to the Grant Program for assisting these new applicants. The city of Sacramento, which used about $100,000 during 2022 on sub-grants to commercial cannabis businesses for making security system improvements, stated that it did not confirm whether applicants had a valid state license. This means that some of Sacramento’s grant recipients may have already held an annual state license, and others may have been new applicants who did not hold a provisional license. In either scenario, the grant funds would not have been used to help a provisional license holder obtain an annual state license. Moreover, staff at the city of San Diego stated that the city does not believe it has any involvement in the process of transitioning provisional licenses to annual state licenses because that process is a DCC responsibility. However, assisting provisional license holders with obtaining an annual state license is the very purpose for which the grantees were awarded these funds.

DCC’s chief deputy director explained that grantees can use the funds for new retail equity applicants but that using the funds on any other type of new applicants is unallowable. She also stated that DCC would clarify the allowable uses of the funds in new guidance to the grantees. Although we did not review supporting documentation for all grant expenditures made by each grantee to date, the information that came to our attention suggests that DCC should be closely monitoring the grantees’ expenditures to ensure that they are related to the purpose for which these funds were appropriated.

If DCC had issued the funds to grantees on a reimbursement basis, it would have been able to request supporting documentation and review the nature of the expenditures before it issued grant funds to grantees for those expenditures. It is unclear why grantees would need the funds immediately if their planned activities required significant lead time, and the chief deputy director confirmed that DCC did not verify whether grantees actually needed the funds so quickly. In fact, many grantees have been slow to spend their funds. As Table 2 shows, the majority of the grantees made minimal expenditures in the first year of the Grant Program, spending only $2 million of the $95 million that DCC awarded, or only 2 percent. In part, some of the delayed spending occurred because DCC was not processing grant amendment requests in a timely manner. However, had DCC retained the funds and paid grantees only when they were able to demonstrate that they had incurred allowed costs, it would have safeguarded against disallowed expenditures.

Some Grantees’ Spending Was Delayed by DCC’s Protracted Responses to Their Amendment Requests

Best practices for federal grant requirements suggest that if a grantee requests an amendment to the grant agreement and the awarding agency takes more than 30 calendar days to consider the request, the awarding agency should inform the grantee in writing of the expected decision date. The agreements that DCC made with the grantees specified a more stringent goal: if a grantee requests a change to the scope of work, budget, or project term, DCC would respond in writing within 10 business days to inform the grantee of whether the proposed changes are accepted. In at least five instances, however, DCC did not adhere to this time frame nor communicate expected decision dates as best practices suggest. Consequently, some grantees did not spend their funds because they were waiting for DCC to determine whether their new proposed use of the funds was allowable. As of April 2023, seven grantees had submitted amendment requests, and DCC had not processed the majority of these amendments promptly, with three grantees each waiting more than 100 days for a decision, as Figure 2 shows.6 These amendment requests include reallocating funds for additional staff, budget modifications, and new consulting contracts.

Figure 2

DCC’s Slow Review of Grant Amendments Has Inhibited Some Grantees’ Ability to Adjust Spending Plans

Source: DCC grant agreements, amendment requests, and email communication.

Note: This figure presents the status of these seven amendment requests as of November 2023, which was the end of our fieldwork.

* In January 2023, DCC sent Monterey an email stating that the amendment request was approved, but DCC indicated to us that it sent the email in error and the request was still under review. As of November 2023, DCC had not yet informed Monterey that the email had been sent in error.

† DCC rejected San Diego’s amendment request after determining that the proposed changes to its expenditures would not go toward transitioning provisional license holders to annual state licenses.

The figure shows a timeline for each of seven local jurisdictions’ (also known as grantees) grant amendment requests and the total number of days it took the Department of Cannabis Control to process those requests, including the number of days the Department of Cannabis Control took to request additional information, the number of days the grantee took to provide the Department of Cannabis Control with additional information, and the number of days the Department of Cannabis Control took to finalize the amendment requests. Across all timelines, we point out two deadlines: a 10-business-day deadline described in the grant agreement for the Department of Cannabis Control to respond to grantees as to whether the proposed scope of work and budget changes are accepted, and a 30-day deadline that we found in federal best practices.

The timelines for five grantees—Sonoma County, Humboldt County, Monterey County, city of San Diego, and Nevada County—show that it generally took the Department of Cannabis Control less than 10 days to request additional information. Similarly, four of the five grantees—Sonoma County, Humboldt County, Monterey County, and city of San Diego—responded to the Department of Cannabis Control’s request within an additional 10 days. However, Nevada County took about 50 days to respond to the Department of Cannabis Control’s request for additional information.

For three grantees—Sonoma County, Humboldt County, and Nevada County—the Department of Cannabis Control approved the amendment requests at about 35 days, 41 days, and 125 days, respectively. The Department of Cannabis Control rejected one grantee’s—city of San Diego—request after a total of about 100 days. We note at the bottom of the figure that the Department of Cannabis Control rejected San Diego’s amendment request after determining that the proposed changes to its expenditures would not go toward transitioning provisional license holders to annual state licenses.

The Monterey County timeline indicates that the Department of Cannabis Control had not finalized its decision as of November 2023. At the bottom of the figure, we indicate that in January 2023, the Department of Cannabis Control sent Monterey County an email stating that the amendment request was approved, but the Department of Cannabis Control indicated to us that it sent the email in error and the request was still under review. As of November 2023, the Department of Cannabis Control had not yet informed Monterey that the email had been sent in error.

For the final two grantee timelines—Trinity County and city of Adelanto—the timelines show that the Department of Cannabis Control received the request in November 2022 but had not processed it as of November 2023. We note at the bottom of the figure that it presents the status of these seven amendment requests as of November 2023, which was the end of our fieldwork.

Several circumstances, including insufficient staffing, have contributed to DCC’s lengthy amendment processing times. In some instances, grantees took weeks or months to provide requested information to DCC. For example, the county of Nevada took 53 business days to provide the information that DCC requested. However, DCC subsequently took another 68 days to review that information.

DCC’s former grants manager attributed such delays to various factors, such as staff turnover, grantees’ struggles to properly address grant agreements, an inefficient process for gathering requested information, a lack of DCC and grantee staff, and her need to prioritize other tasks. She also stated that the exhibit that set forth the 10-business‑day deadline had been included in the agreements in error and would be removed in subsequent amendments to the agreements, and she contended that having deadlines for amendment determinations was not feasible because of insufficient staffing.

The long amendment processing times have had negative consequences for some grantees. For example, although DCC ultimately approved the county of Nevada’s amendment request, it took DCC more than three months to do so after it received additional information from the county, and a senior technician in the county’s Cannabis and Code Compliance Divisions stated that the delay prevented the county from progressing toward its Grant Program goals.

Similarly, the county of Trinity, which submitted an amendment request in late November 2022, had not received a decision from DCC a year later, as of November 2023. The director of the county’s Cannabis Division stated that the uncertainty around its amendment was limiting the county’s ability to pursue opportunities for using its remaining grant funds, such as for acquiring new software to streamline its permitting processes.

After we discussed the amendment process with DCC in May 2023, DCC created a flowchart of the process it established for reviewing amendment requests. However, the documentation DCC provided does not establish any time frames for the steps in the process or for the total review process. Considering the short lifetime of the Grant Program, it is imperative that DCC establish, communicate, and uphold reasonable time frames for processing amendment requests.

To Improve Its Management of the Grant Program, DCC Could Have More Effectively Used the Administrative Funds It Was Appropriated for the Program

The Budget Act of 2021 authorized DCC to use up to 5 percent of the total amount appropriated for the Grant Program, or up to $5 million, for administrating the program during the approximately four years of the grant’s lifespan. Although the Budget Act took effect in July 2021, DCC’s deputy director of administration explained that DCC did not establish its OGM until January 2022. More than a year later, OGM was staffed in May 2023 with only a single grants manager to handle all 17 jurisdictions. It had previously also employed a grant management analyst. Both the grants manager and the grant management analyst were also responsible for managing at least one other grant program. Thus, just two people were tasked with administering the $100 million Grant Program, and on a part-time basis.

Notwithstanding the $5 million it was appropriated to administer the Grant Program, DCC’s limited number of grant management staff resulted in insufficient oversight of the grantees. As of February 2023, DCC had used only $350,000 of the $5 million appropriated to it for program administration, or about 7 percent. DCC was on track to spend only 25 percent of the $5 million in administrative funds in the remaining two-and-a-half years before the Grant Program ends. However, the consequences of understaffing were evident in the oversight tasks DCC had not performed, such as assessing whether costs were allowable and processing grant agreement amendment requests in a timely manner. When we discussed these neglected oversight tasks with DCC’s former grants manager, she stated that she did not have the time or resources to implement best practices or perform expected administrative tasks. Thus, there was an evident need for additional staff to provide oversight of the Grant Program.

Even though DCC experienced an increasing backlog of tasks that were not being completed, it had not developed a plan for how it would use the administrative funds it was appropriated to administer the grant. As of July 2023, despite our repeated requests, DCC had not provided a budget for how it initially planned to use the $5 million appropriated to it to administer the grant. Our interviews with DCC management suggest that there was a lack of effective internal communication about the insufficient resources and no plan in place to evaluate staffing needs. The chief deputy director told us in May 2023 that she was not aware of any problems with administering or overseeing the grant or grantees because of insufficient staff.

In contrast, the deputy director of administration stated around the same time in May 2023 that she had requested staff to perform a workload analysis to determine the appropriate number of staff for the OGM now that its duties were better known. However, at that time, DCC was not tracking the amount of time that any of the staff paid with grant funds spent on the Grant Program. It did not begin to do so until July 2023, after we had shared our concerns.

Further illustrating DCC’s inadequate communication involving staffing, the operations branch chief explained in May 2023 that she had held informal conversations with her supervisors about the lack of staff but had not formally presented her concerns to executive management because she first wanted to collect information demonstrating the amount of time and work the Grant Program required. By then, additional problems had emerged, including delays in processing amendment requests, and DCC not defining the term substantial progress so that grantees would know what they needed to accomplish to receive the remaining 20 percent of funds. The operations branch chief stated at the end of May 2023 that she had begun using staff from other areas to assist with the administration of the Grant Program.

After DCC received our July 2023 management letter outlining our concerns about insufficient staffing, it hired additional staff. By February 2024, the OGM included four staff with Grant Program responsibilities: a grants manager, two grants management analysts, and a retired annuitant. In November 2023, the deputy director of administration provided us with a spending plan for $3.3 million of the administrative funds.

Some of the administrative funds DCC did spend were used for unallowable costs: those funds paid the salaries of staff whose tasks sometimes involved work not related to managing the Grant Program and sometimes involved completely different grants. The $350,000 that DCC had used as of February 2023 was spent on the salaries of the grants manager, a grants management analyst, and four environmental scientist positions. However, the four environmental scientists were tasked with processing license applications, which was not an activity directly related to managing the Grant Program. According to a DCC supervisor who manages two of the environmental scientists, his team does not work on assisting provisional license holders with obtaining an annual state license. In addition, although the grants manager and grant management analyst worked on multiple grant programs, their entire salaries were paid for by this Grant Program.

When we informed DCC in July 2023 of our concerns about these expenditures, it took steps to address them. The chief deputy director agreed that the routine processing of license applications—the work the environmental scientists were completing—was not an activity that should be charged to the administration of the grant. She stated that she assumed the environmental scientist staff were dedicated to Grant Program activities. To address this issue, DCC identified those staff that it allowed to charge time to the Grant Program and in October 2023 made corrections to move the related expenditures from the Grant Program to another fund. Further, in July 2023, DCC began tracking the time staff reported spending on activities related to the Grant Program.

The results of the first month of tracking time in this way show that the staff in the licensing division who worked on the program spent between 0 percent and 8 percent of their time on grant-related activities and that the former grants manager spent about 64 percent of her time on the program. The deputy director of administration stated in November 2023 that DCC estimated the amounts that were incorrectly spent in the past and that its accounting staff had completed the expenditure corrections to reimburse the Cannabis Control fund for the misspent administrative funds.

DCC’s Grant Management Staff Did Not Have Sufficient Expertise to Manage a Program of This Complexity

State law authorizes DCC to undertake certain duties in administering the Grant Program, including—but not limited to—promulgating grant rules and recapturing disbursed funds if grantees fail to demonstrate progress. However, DCC staff did not have the expertise necessary to manage a program of this size. As a result, DCC staff have made a number of decisions that do not align with best practices.

DCC staff themselves attributed some grant management mistakes to their own lack of experience. For example, the former grants manager attributed the erroneous inclusion of exhibits in the grant agreements—such as the 10-business‑day deadline—to her lack of experience preparing these type of documents. Therefore, we would have expected DCC to conduct a thorough review to ensure that the agreements were appropriate. However, the operations branch chief, the person who signed the grant agreements for DCC, stated that she did not review the agreements and that the deputy director for administration had reviewed them instead. She believed that dividing the review and signature of the agreements was intended to maintain a separation of duties that she claimed was required by the State Administrative Manual. However, we were unable to identify any such requirement or rationale for such a requirement. The deputy director for administration who reviewed the agreements was unable to explain why her review did not identify the erroneous exhibits, and she attributed their inclusion in the grant agreements to human error.

DCC staff also did not clearly delineate certain responsibilities regarding program oversight, creating gaps in processes and accountability. For example, the former grants manager stated that the grantees’ progress is reviewed by DCC’s licensing division. However, a supervisor in the licensing division explained that her division does not set benchmarks or metrics to track a grantee’s progress. Thus, it was not clear who was responsible for determining whether the Grant Program was on track to accomplish its purpose. Although the licensing division supervisor provided a spreadsheet showing the number of provisional licenses that were still active in each month, DCC did not establish any expectations for grantees’ progress or determine at what rate licenses needed to be transitioned to ensure that the Grant Program would achieve its primary goal of helping provisional license holders obtain annual state licenses.

Similarly, the information DCC asked grantees to provide in their biannual reports was not always necessary or useful. For example, the template DCC provided to the grantees for the initial biannual report due in August 2022 did not direct the grantees to report their actual expenditures. Instead, it directed grantees to provide their budgeted expenditures, information they had already provided in their original grant application. Thus, DCC was not able to determine how much the grantees had spent during the first six months of the program. DCC modified the biannual report template for the February 2023 reports to request grantees to report actual expenditures. However, grantees collectively spent only 2 percent of the funding that DCC awarded.

DCC also required grantees in the February 2023 and August 2023 reports to provide the numbers and status of provisional and annual state licenses issued to applicants in their jurisdictions. However, because DCC already maintains these licensing data, it is unclear why DCC would ask grantees to report the same licensing data. In response to our questions, DCC eliminated the requirement to submit state license data for the February 2024 biannual report.

DCC also did not provide grantees with guidance on how to manage the grant funds they received. In particular, DCC did not specify whether grantees should put the funds in interest-bearing accounts or what they were to do with accumulated interest. State law directs all money belonging to or in the custody of a local agency to be deposited with certain types of financial entities or to be invested in specified investments authorized by law. Case law also establishes that interest generally must be used for the same purpose as the principal from which it was earned, meaning that grantees must use this interest for the Grant Program. Grant agreements commonly define whether funds are to be kept in an interest-bearing account and how the interest is to be used. However, DCC’s grant agreements with the 17 grantees did not include these provisions. As we note in Table 2, many grantees have received but not spent significant amounts, so interest earned on these funds should be used for the grant’s intended purpose.

The former grants manager stated that DCC did not provide guidance on how to manage any interest earnings because it did not occur to staff that the interest from the funds would be an issue or that it was DCC’s responsibility to provide such guidance, highlighting a lack of experience in managing a grant program. Moreover, we found that 10 grantees were not dedicating interest earned on the funds to the purpose of the Grant Program. For instance, the city and county of San Francisco did not dedicate to the Grant Program the $20,000 in interest that it earned as of December 2022 on its $3.1 million in Grant Program funds. In contrast, the city of San Diego had earned more than $4,800 in interest as of March 2023 on the $611,000 in Grant Program funds that DCC advanced the city—interest that San Diego credited to the grant.

Because DCC chose to advance 80 percent of the funds instead of issuing them on a reimbursement basis, communicating with grantees about how to deal with interest should have been a priority for this Grant Program as it is for federal grant programs. In November 2023, DCC developed guidance related to interest earned on grant funds, although the guidance did not explicitly recommend that the grantees place the funds in interest-bearing accounts or clarify that the accrued interest on those funds must be used for the purpose of the Grant Program. In addition, DCC stated in March 2024 that it only provides the guidance to grantees upon request, and only the city and county of San Francisco had requested the information.

The chief deputy director explained that at the time the Grant Program was established, no one at DCC had much experience with grant management. In particular, she said that no one anticipated the complexity and workload that would be involved in administering the program. The former grants manager explained that her experience with grant programs was confined to the application process and that she had not previously performed any post-award administrative work. She also explained that she had cross-trained with the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s grants program when she became the grants manager at DCC, but that those grants differed greatly from the Grant Program. Moreover, the operations branch chief and deputy director of administration stated that although they had some experience with federal grants, they had not found their past experience particularly applicable to the Grant Program.

After we raised in our July 2023 management letter our concerns about staff’s inexperience, DCC indicated in October 2023 that it was enrolling its OGM staff in several training classes, including a class on federal grants. As of March 2024, the OGM staff had taken these grant-related training classes, and DCC had a contract in place to provide staff with recurring annual training on grant management practices. These are useful steps that may result in stronger grant management practices at DCC in the long run. However, time is short since the Grant Program’s funds revert to the State’s General Fund if not expended or encumbered by June 30, 2025.

Recommendations

DCC

To better align its management of grant programs with best practices, by February 2025, DCC should institute a grants management policy. This policy should accomplish the following actions at a minimum:

- Designate the DCC staff member responsible for determining that proposed activities and costs are allowable during the grant review process.

- Establish a process to ensure that each element of the policy has been reviewed, such as reviewing costs for allowability.

- Establish benchmarks or other criteria in grant agreements for measuring grantee progress toward a grant program’s goals.

- Specify the preferred method for disbursing grant funds, taking into account common grant management best practices.

- Establish an amendment review process that includes internal and external deadlines to ensure DCC processes amendments in a timelier manner.

- Establish procedures for monitoring expenditures and determining their allowability.

- Establish a method to track the time that DCC staff spend working on grant‑related activities.

To provide grantees with timely feedback about whether their spending is allowable or whether they will be required to return funds, DCC should immediately begin reviewing grantees’ expenditures to determine whether their expenditures are appropriate and begin communicating those determinations to the grantees.

To help ensure that state grant funds and related interest benefit only the Grant Program, DCC should immediately recommend that all grantees place any unspent grant funds in interest-bearing accounts. Further, DCC should direct grantees to track and report to DCC any interest accrued from those funds, and clarify that the accrued interest be used only for the purpose of the Grant Program.

Chapter 2

Some Grantees Did Not Manage Their Grant Funds Properly

- We found that four of the 17 grantees did not adequately track their grant funds, two grantees did not track and document whether staff time was spent on tasks related to the grant, and two grantees charged expenditures to the Grant Program that were unrelated to its purpose.

- Noncompliance with the Grant Program’s requirements risks DCC disallowing expenditures that the grantees intended to pay for with grant funds.

DCC’s Ability to Accurately Track Spending Is Hindered by Four Grantees That Did Not Properly Account for All Grant-Related Financial Transactions

Many of the grantees tracked their expenditures, but four of 17 did not do so. As part of our review of grantees’ expenditures, we obtained financial data from each grantee and determined whether the grantee’s receipt of grant funds—as well as its expenditure of grant funds, if any—had been properly assigned to the Grant Program. The GFOA suggests that grantees establish a grant fund, or unique project identifier, to account for the relevant financial transactions. This guidance can help ensure that grantees properly attribute expenditures to the grant.

The agreements between DCC and the grantees also require grantees to maintain adequate documentation of transactions so that DCC can evaluate whether the expenditures are allowable. We found that four of the 17 grantees we reviewed did not adequately track their grant funds. Two grantees—the city of Commerce and the county of Trinity—did not establish a unique identifier for their grant funds, as Table 3 shows, and the city of Long Beach underreported its expenditures because it did not attribute them to the grant in its financial system in a timely manner.

Not properly tracking expenditures of grant funds can cause several problems. A grantee that does not properly track grant funds might commingle Grant Program funds with other grants and revenues, making it unclear to what program the funds or associated expenditures belong and risking that the grantee will spend the funds on unallowable activities. Further, when grantees do not accurately track expenditures, they limit their own ability to appropriately budget their remaining grant funds as well as limit DCC’s ability to determine how much and how quickly they are spending the funds. Finally, grantees increase the risk that they will use their own funds to pay for grant-related expenditures if the grantees are not properly recording them as grant expenditures in their accounting systems. For example, as we describe in Table 3, the county of Humboldt used its general fund to pay for approximately $1,700 in grant-related expenditures because it did not accurately record expenditures in its financial system. After we brought these issues to the grantees’ attention, they resolved some problems, as Table 3 shows. Nevertheless, we still make recommendations to three grantees to ensure that they appropriately track and record their grant expenditures.

Some Grantees Could Not Justify Staff Costs Charged to the Grant Program

Federal regulations establish standards for the accounting of personnel costs paid with grants, as the text box describes, which we considered to be best practices. Further, DCC’s Grant Program guidelines from October 2021 specify that salary and wage amounts charged to the grant must be based on an adequate payroll system. As part of our review, we evaluated a selection of expenditures for each grantee, such as staff costs and contractor invoices, for compliance with key grant agreement terms. Two grantees, whose actions we describe in Table 4, did not track and document the time employees spent working on grant-related projects. The city of Commerce simply estimated the hours that staff would spend on projects related to the Grant Program and then allocated a fixed percentage of their salaries to the grant. The county of Mendocino retroactively estimated the hours at some point after the work was performed. Neither grantee maintained contemporaneous information to support its determination of personnel costs. Thus, neither grantee could demonstrate that it had complied with the DCC requirement that employee compensation be based on an adequate payroll system and be supported with adequate documentation. When we informed DCC of these issues in late November 2023, its operations branch chief stated that DCC would need to review the expenditures itself before determining the appropriate course of action. Nevertheless, DCC began providing guidance to grantees in December 2023 about how to document staff time for grant-related projects.

Federal Standards for Accounting for Staff Time Charged to a Grant

- Charges for salaries and wages must be based on records that accurately reflect the work performed.

- Charges must be supported by a system of internal controls that provide reasonable assurance that those charges are accurate, allowable, and properly allocated.

- Records must comply with the established accounting policies and practices of the entity.

- Records must reasonably reflect the total activity for which employees are compensated by the entity.

- Budget estimates alone do not qualify as support for charges to grant awards.

Source: 2 Code of Federal Regulations part 200.430.

Without documentation to support these expenditures, the two grantees were not able to provide us with adequate assurance that the charges to the Grant Program were allowable under the terms of their grant agreements. Thus, it is unclear whether these expenditures contributed to achieving the Grant Program’s goals or whether DCC will require the funds to be returned.

Two Grantees Spent Grant Funds Inappropriately, Totaling $26,000 in Questioned Costs

Of the 17 grantees we reviewed, two grantees spent grant funds totaling $26,000 on purposes unrelated to the Grant Program or were unable to substantiate that their spending was for allowable costs. DCC’s Grant Program guidelines require that all Grant Program expenditures must be for activities, products, and costs that have been included in an approved grant application proposal and budget. Additionally, state law specifically prohibits using the Grant Program funds to supplant existing cannabis-related funding. Supplanting occurs when a grantee reduces its existing spending for an activity because it is using grant funds or expects to use grant funds to fund that same activity. Supplanting may constitute a material breach of the grant agreement, is a violation of state law, and could result in DCC recapturing the grant funds. Federal best practices indicate that if a question of supplanting arises, it is the grantee’s responsibility to substantiate that the reduction in local spending occurred for reasons other than the receipt or expected receipt of grant funds.

Through our review of a selection of expenditures among the grantees, we identified two grantees that had charged unallowable costs to the Grant Program. Table 5 describes these instances. Although the purposes for which one grantee used the funds were allowable, the grantee was unable to demonstrate that it did not use the funds to supplant its existing cannabis-related funding. In the other instance, the grantee used the funds for purposes other than helping provisional licensees obtain annual state licenses. Although neither of the grantees spent a significant portion of their total funds on these inappropriate expenditures, the occurrence of these expenditures indicates that the grantees were not adequately assessing whether the expenditures should be charged to the grant. If the rate at which the grantees spend grant funds increases in order to spend all of the funds by March 2025, their failure to determine whether spending is appropriate could lead to significant misspending. Such misspending could reduce the likelihood that the Grant Program will achieve its intended results.

Recommendations

City of Commerce

To reduce the risk that DCC will require it to repay grant funds, the city of Commerce should immediately cease using grant funds in a manner that may supplant existing funding for its staff and contractors, review all expenditures it has paid for with grant funds, and reimburse Grant Program funds from its general fund for any unallowable or supplanted expenditures.

County of Humboldt

To ensure that it pays for all grant-related costs from the grant funds it has received, by February 2025, the county of Humboldt should accurately reconcile its grant expenditures before its fiscal year-end close.

City of Long Beach

To improve its ability to appropriately budget its grant funds and DCC’s ability to determine how much of those funds the city is spending and how quickly it is spending them, by October 2024, the city of Long Beach should develop grant management procedures that establish a method for the accurate and timely accounting and reporting of grant-related expenditures.

City of San Diego

To reduce the risk that DCC will require it to repay grant funds, by October 2024, the city of San Diego should review all expenditures it has paid for with grant funds, clarify with DCC whether the expenditures are allowable, and reimburse the grant funds from its general fund for any unallowable expenditures.

Chapter 3

The Grant Program May Not Achieve Its Goals, and DCC Cannot Determine the Causes of Delays in License Processing

- After the Grant Program’s first year, a relatively small number of provisional license holders in the grantees’ jurisdictions obtained an annual state license. The slow rate at which grantees spent their funds likely contributed to the lack of progress.

- On average, provisional licensees spent nearly two years to obtain annual state licenses in 2022. DCC did not consistently track a sufficient amount of data about the timeliness of its licensing process to thoroughly analyze the causes of lengthy processing times.

The Rate of Progress During the Program’s First Year Raises Concerns About Whether the Grant Program Can Achieve Its Purpose

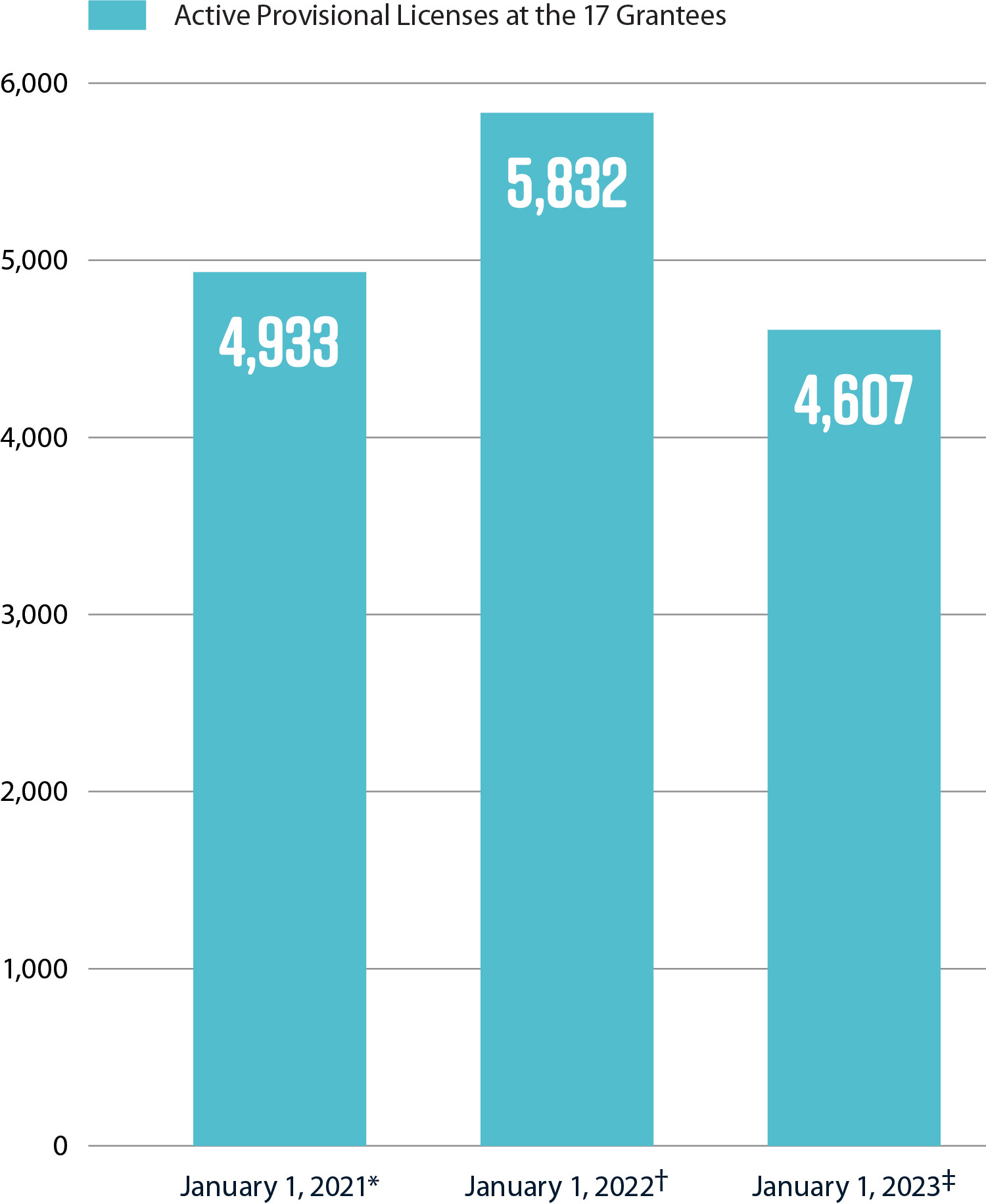

During the first year of the Grant Program’s four-year lifespan, grantees made limited progress toward the program’s primary purpose of assisting provisional license holders to obtain an annual state license. State law requires grantees to expend or encumber grant funds by June 30, 2025, and provisional licenses issued by DCC will no longer be effective after January 2026, with limited exceptions. However, grantees are not on track to transition all of their licenses before they expire. During 2022—the first year of the Grant Program—only 535 provisional license holders obtained an annual state license.

Figure 3 shows that more than 4,600 provisional licenses still needed to transition to annual state licenses as of January 1, 2023. State law enabled DCC to continue issuing provisional licenses during 2022, and DCC can continue issuing provisional licenses to qualified equity retail applicants until 2031. Newly issued provisional licenses thus increased the number of provisional license holders between 2021 and 2023 that must obtain an annual state license. If DCC continues to issue the same number of annual state licenses to provisional license holders that it did during 2022, more than half of the provisional license holders in the grantees’ jurisdictions will still not have obtained an annual state license by 2026.

It is not clear whether the grantees resolved the problems that prevent provisional license holders from obtaining annual state licenses in a timely manner. DCC directed jurisdictions to identify in their grant applications the permitting process challenges that impeded provisional license holders’ transition to annual state licenses, and DCC required those jurisdictions to specify their goals and intended outcomes. Each jurisdiction described goals or actions associated with its use of the funds, such as hiring staff or contractors to decrease applicants’ wait time for CEQA environmental reviews. The jurisdictions’ use of their grant funds varied. However, DCC did not ensure that the grant agreements contained measurable benchmarks or metrics. In fact, DCC approved four grantees’ grant agreements even though they did not provide goals. It is therefore difficult to assess the grantees’ progress toward addressing the challenges they had identified. The relatively small number of provisional licenses transitioned to annual state licenses in the first year of the four‑year program is not promising, although certain factors likely impeded progress during the Grant Program’s first year.

Figure 3

A Significant Number of Provisional Licenses at the 17 Grantees Remained Active in January 2023

Source: Analysis of DCC’s manufacturing, cultivation, and retail and distribution licensing systems.

*Because of limitations in the manufacturing licensing system, manufacturing licenses are excluded from the count of provisional licenses that were active as of January 1, 2021.

† The issuance of new provisional licenses contributed to the increase in provisional licenses between 2021 and 2022. Further, the inclusion of manufacturing licensing data, which are not present in the analysis for 2021, adds approximately 400 active provisional licenses to the count for 2022. Appendix A presents further details on the numbers of provisional and annual state licenses at all 17 grantees.

‡ Because of inconsistent information contained in the manufacturing licensing system and printed on the license certificates, we were unable to discern whether eight licenses that were active as of January 2022 or January 2023 were in provisional or annual status. We counted them as provisional for the purpose of this figure.

The first bar on the graph shows 4,933 active provisional licenses at the 17 grantees as of January 1, 2021. We note at the bottom of the graphic that because of limitations in the manufacturing licensing system, manufacturing licenses are excluded from the count of provisional licenses that were active as of January 1, 2021.

The second bar on the graph shows 5,832 active provisional licenses at the 17 grantees as of January 1, 2022. We note at the bottom of the graphic that the issuance of new provisional licenses contributed to the increase in provisional licenses between 2021 and 2022. Further, the inclusion of manufacturing licensing data, which are not present in the analysis for 2021, adds approximately 400 active provisional licenses to the count for 2022. Appendix A presents further details on the numbers of provisional and annual state licenses at all 17 grantees.

The third bar on the graph shows 4,607 active provisional licenses at the 17 grantees as of January 1, 2023. We note at the bottom of the graphic that because of inconsistent information contained in the manufacturing licensing system and printed on the license certificates, we were unable to discern whether eight licenses that were active as of January 2022 or January 2023 were in provisional or annual status. We counted them as provisional for the purpose of this figure.

We found that on average, provisional license holders in the 17 Grant Program jurisdictions obtained annual state licenses during 2022 at approximately the same rate they had during the year before the jurisdictions received the grant funds. Grantees expended a limited amount of grant funds during that first year, which may have contributed to the relatively small number of provisional license holders that obtained annual state licenses. The grantees’ overall slow pace in spending their grant funds is understandable in some cases because, for example, it can take time to recruit new staff or to execute contracts. Nevertheless, grantees’ minimal grant fund expenditures during the program’s first year likely resulted in the Grant Program’s minimal initial impact.

We selected six of the 17 grantees for additional review, basing our selection in part on the rate at which provisional license holders in their jurisdictions had obtained annual state licenses. Table 6 identifies the six grantees, describes their use of the grant funds during 2022, and quantifies their progress toward helping provisional license holders transition to annual state licenses. As the table shows, grantees encountered some barriers to progress, such as a delay in hiring new staff, or in the case of one grantee, delayed city council action that held up until June 2023 changes to its application process that would facilitate provisional license holders transition to annual state licenses.

Moreover, the progress one grantee made does not appear to be attributable to its use of the grant funds. Even though provisional license holders in the county of Humboldt have obtained annual state licenses at a higher rate than those at many other grantees, the county’s grant agreement indicates that it plans to use a portion of its funds for purposes unrelated to the intent of the Grant Program. The county’s director of planning and building stated that the county’s progress could be credited to the county’s development of regulations that, when complied with, meant that local cannabis businesses were prepared to meet the state requirements.

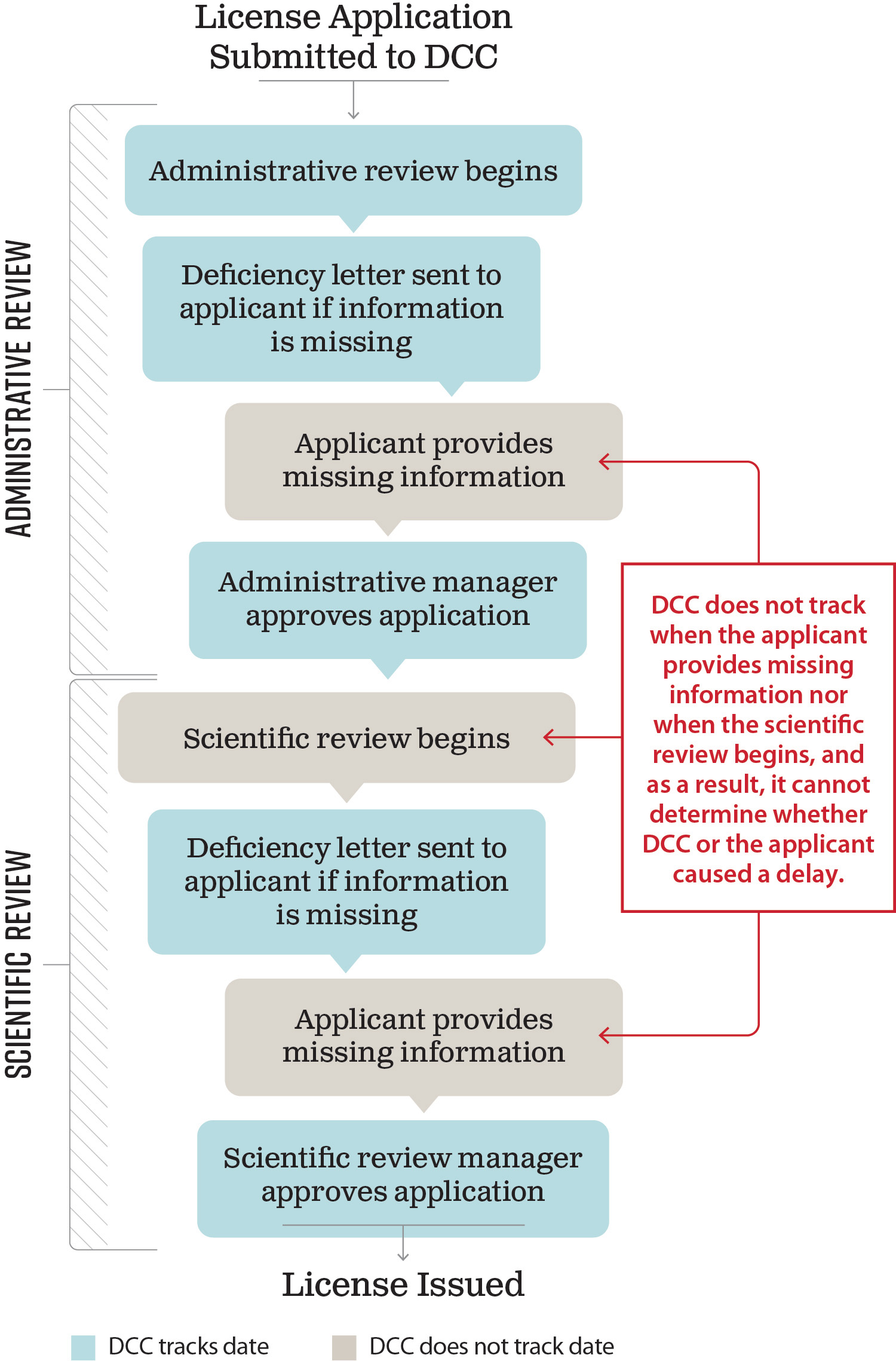

DCC Does Not Track the Timeliness of Its Licensing Process

The process for a provisional license holder to obtain an annual state license takes an average of nearly two years. Local permitting plays a significant role in the process of obtaining an annual state license, but it is ultimately DCC’s responsibility to issue those licenses. We reviewed DCC’s licensing data for each license type, and we determined the average processing times for annual state license applications in each grantee’s jurisdiction. We found that on average, it took nearly two years for provisional license holders to obtain an annual state license, regardless of license type. In some cases though, provisional license holders had already held a provisional license for more than three years and were still actively in the process of obtaining an annual state license. However, DCC lacks the needed data to evaluate the timeliness of its license review process.

The process takes significantly longer in some grantees’ jurisdictions. For example, it took provisional cultivation license holders in the county of Monterey more than three years on average to obtain an annual state license, whereas the same process took only a little more than a year on average in the county of Lake. Appendix B presents additional information on the time it took DCC to process annual state license applications for each license type for applicants in each grantee’s jurisdiction.

We attempted to review DCC’s licensing data to determine why it takes so long to process these applications. During the period of our review, DCC used three different data systems—the systems it inherited from the three agencies that previously regulated cannabis businesses—to manage the licensing for specific categories of cannabis businesses. DCC uses a cultivation licensing system, a manufacturing licensing system, and a system for retail, distribution, and other types of cannabis licensing (retail license system).

We expected that the three licensing data systems would each contain the information necessary to evaluate DCC’s license review process. Although we found that the systems do track some information about the process, they lack key data necessary to determine why the process takes as long as it does. As an example, Figure 4 shows that the cultivation licensing system does not track all of the information necessary to determine whether long application processing times are attributable to DCC or to the applicant. For instance, it was not possible to determine from the data how long it took DCC to complete the scientific review phase, during which DCC verifies that the applicant has completed the CEQA process.

A DCC environmental supervisor described other data limitations. For instance, in the retail licensing system, when a provisional retail license changes to an annual state license, DCC staff must enter new approvals in the application’s records to verify that all requirements have been met for issuing the annual state license. This action results in the environmental supervisor no longer having access to the original dates an application entered certain phases. Further, according to a supervisor in DCC’s licensing division, DCC does not create or store hard copy files documenting all the relevant steps in the application process for each of the three licensing systems because all information is filed electronically.

DCC has also not completely tracked the deficiency letter process—the initial sending of the letter to an applicant outlining the information the applicant still needs to provide and the subsequent receipt of the requested documents. Figure 4 shows that although the cultivation licensing system tracks when DCC sends a deficiency letter to applicants, it does not record when applicants provide the missing information. The deputy director of DCC’s licensing division confirmed that for the other two systems, DCC has either not tracked the deficiency letter process in the system or only began doing so recently.

DCC does not currently have a plan for better tracking the data necessary to evaluate the timeliness of the licensing process. However, DCC is making other changes to improve its licensing data management. DCC completed migrating the manufacturing licensing system onto the software platform used by the other cannabis licensing systems in April 2024. The deputy director of licensing said DCC also plans to modify the cultivation and retail licensing systems in spring 2024 to provide the opportunity for the two systems to more easily communicate with each other.