2024-109 California Department of Housing and Community Development

Increased Support Is Critical for Local Jurisdictions to Complete Timely Housing Plans

Published: January 15, 2026Report Number: 2024-109

January 15, 2026

2024‑109

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to evaluate its oversight of cities’ and counties’ (local jurisdictions) submissions of housing elements and HCD’s procedures for reviewing housing elements. HCD interprets the housing element law and determines whether local jurisdictions’ housing elements substantially comply with it. HCD then issues findings letters to local jurisdictions to notify them of its compliance determination, but the law does not require these letters to provide prescriptive instruction for achieving compliance.

We found that HCD’s findings letters generally provide valuable feedback to local jurisdictions; however, jurisdictions that are struggling to develop compliant housing elements also require individualized assistance. The complexity of new legal requirements, increased housing allocations, and community resistance to new development, mean that most local jurisdictions required multiple submissions and significant time to achieve compliance during the sixth housing element cycle. HCD met legal deadlines for reviewing submissions for 10 selected local jurisdictions, but those jurisdictions told us that individualized assistance from HCD was important to help them understand and address the department’s findings. Although HCD offers detailed online guidance to help jurisdictions, it did not always release this guidance in a timely manner.

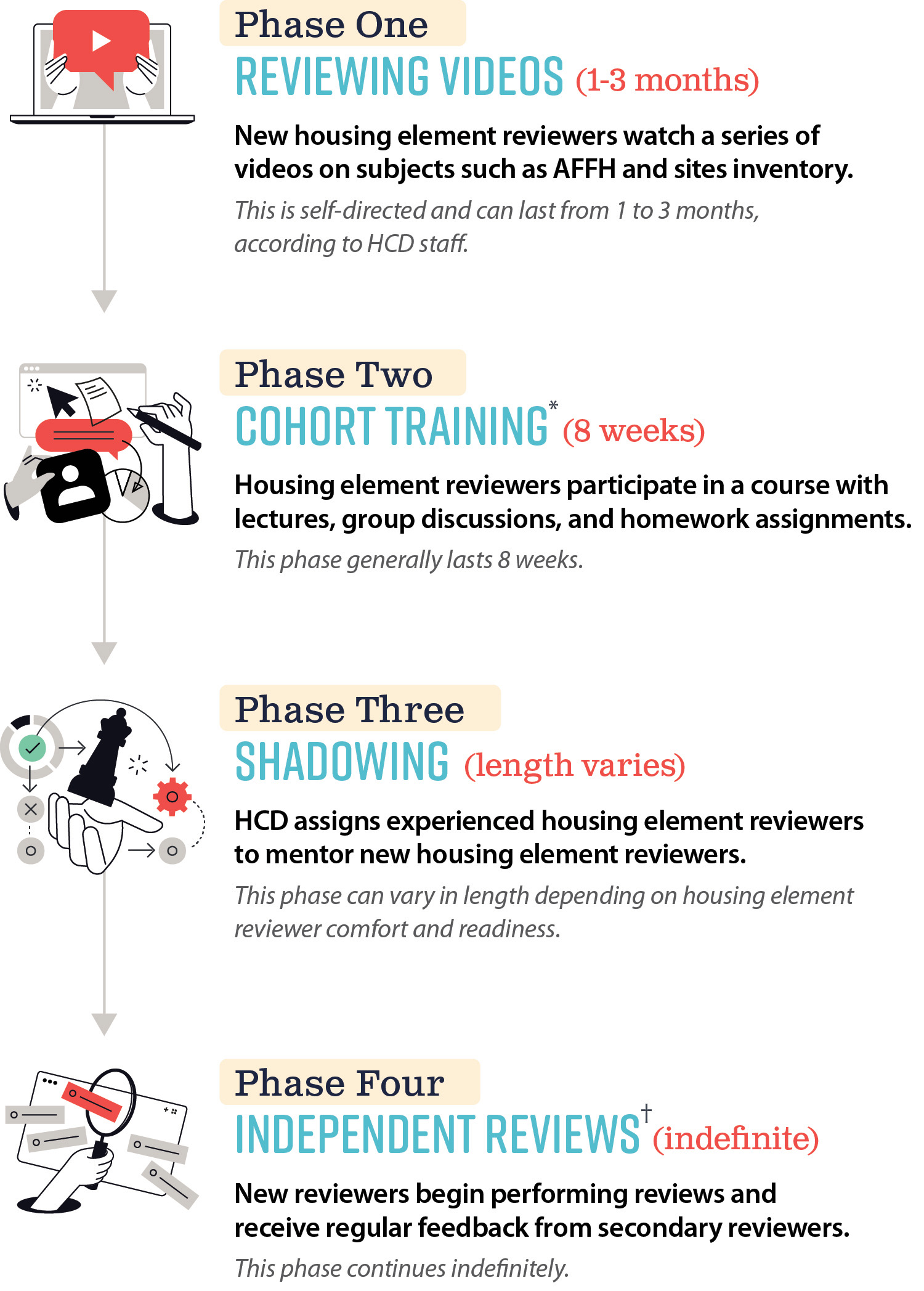

Staff availability during its peak workload constrained HCD’s ability to provide important individualized assistance to local jurisdictions. Even with HCD’s comprehensive training program for new reviewers and reliance on experienced secondary reviewers to ensure consistency, turnover and overlapping submission deadlines have strained its capacity. To improve the housing element review process, we recommended that HCD conduct a workforce analysis and implement more consistent communication practices, and the Legislature could consider staggering submission deadlines to reduce HCD’s workload surges.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ABAG | Association of Bay Area Governments |

| AFFH | Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing |

| COG | Councils of Governments |

| HCD | California Department of Housing and Community Development |

| PLHA | Permanent Local Housing Allocation |

| SCAG | Southern California Association of Governments |

Summary

Results in Brief

Over the course of the past decade, California has experienced a housing supply crisis. The consequences for the State’s residents have been significant: many are struggling with financial vulnerability and homelessness. Cities and counties—which this report refers to as local jurisdictions—play a critical role in responding to this crisis. Since 1969, state law has required local jurisdictions to develop and implement strategies to address their housing needs across all income levels through housing elements. These housing elements are a part of the jurisdictions’ general plans, which are blueprints for growth that also address issues such as transportation, noise, and safety. Housing element law provides broad requirements that accommodate all the diverse local jurisdictions throughout the State. The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) interprets, applies, and determines whether housing elements comply with the housing element law but cannot dictate to local jurisdictions how they specifically choose to achieve compliance. The broad requirements that maintain local discretion create a dynamic of power sharing between the State and local jurisdictions that necessitates a dialogue during the review process.

Most local jurisdictions must revise their housing elements at least every eight years—a length of time referred to as a cycle. Most local jurisdictions are currently either in the process of completing or recently completed their sixth-cycle update. During each cycle, HCD is responsible for reviewing the local jurisdictions’ revisions to determine whether they comply with state law requirements, which we discuss in the Introduction. Local jurisdictions that fail to adopt HCD-approved, revised housing elements can face significant consequences, such as legal challenges, condensed rezoning timelines, and ineligibility for some sources of funding.

Given the complexity of the process for housing development planning, most local jurisdictions must submit two or more drafts to HCD during each cycle before the department is able to determine that the drafts comply with state law and the local jurisdiction adopts its compliant housing element. This submission and approval process was particularly lengthy during the sixth cycle. During this cycle, the median time from which a jurisdiction submitted its initial draft housing element until it received HCD’s approval was more than one year, a 126 percent increase in duration compared to the fifth cycle. Nevertheless, we found that HCD met its statutory deadlines for reviewing and providing its determinations to the 10 jurisdictions we selected for review. Instead, the longer approval process was generally due to the time local jurisdictions needed to revise their housing elements because of factors such as new legal requirements, community opposition to building new housing, and the increase in new housing unit allocations from the State that local jurisdictions must plan for in their housing elements.

To help local jurisdictions develop compliant housing elements, HCD provides three types of assistance: formal letters in response to local jurisdictions’ draft housing elements that detail the department’s findings (findings letters); one-on-one meetings and correspondence directly with local jurisdictions (individualized assistance); and online guidance and resources. Although the housing element law requires HCD to report its findings to local jurisdictions in writing, it does not require these findings letters to provide local jurisdictions with guidance or prescriptive instruction on how to achieve compliance. HCD’s findings letters typically include a citation to the relevant section of state law, an explanation of the requirements of that section, and some additional examples and suggestions for how the local jurisdiction might meet the requirements. We determined that the HCD findings letters we reviewed are precise, measurable, and based on criteria—that is, supported by law or online guidance. However, we identified one instance in which HCD did not use consistent language to indicate to a local jurisdiction what was a requirement and what was a suggestion. Nevertheless, we found that HCD generally used consistent feedback between jurisdictions for similar findings. Although we determined that HCD’s findings letters provide meaningful, precise feedback that is supported in law or guidance, HCD should also provide individualized assistance to jurisdictions who are struggling to develop compliant housing elements. Specifically, eight of the 10 local jurisdictions expressed the sentiment that the letters alone were not sufficient to allow them to understand how to address HCD’s findings and develop a compliant housing element. Both HCD and many of the local jurisdictions emphasized the importance of individualized assistance. This assistance provides the opportunity for local jurisdictions to work with HCD to resolve complex findings. Nine of the local jurisdictions we interviewed indicated that individualized assistance, in combination with the findings letters, helped them address HCD’s findings. However, HCD’s high workload prevents it from always providing such support.

HCD also publicly provides detailed online guidance but did not always issue timely guidance. HCD currently provides many different forms of online help to local jurisdictions, including requirements for each section of the housing element, explanations of state law, sample analyses, templates, and checklists. However, HCD did not issue comprehensive guidance for two significant changes in law in a timely manner. In these cases, guidance was not issued until after some local jurisdictions had already passed their deadlines for addressing those changes. HCD management explained that the timelines for releasing guidance vary greatly depending on the significance and complexity of the changes in law.

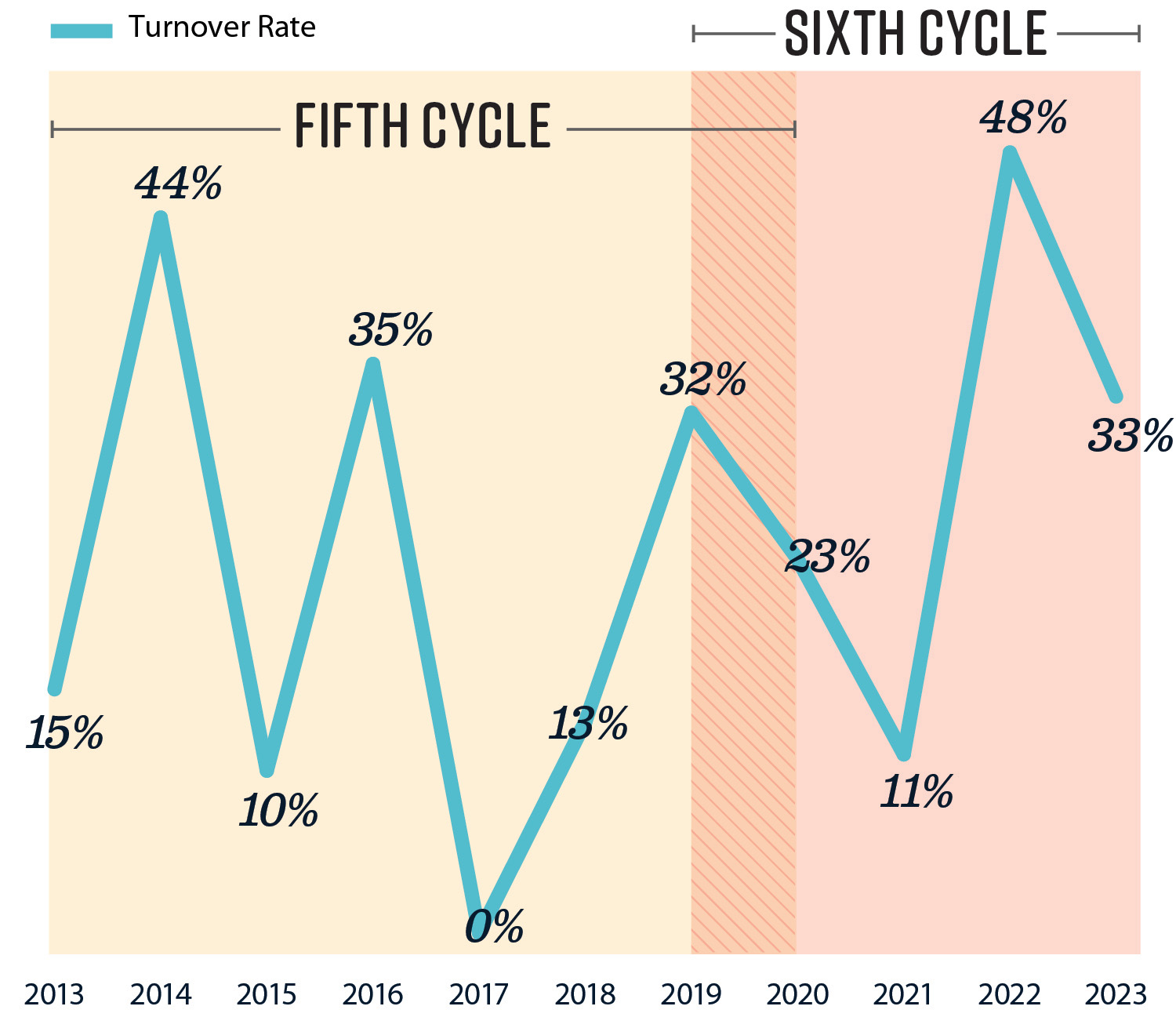

HCD’s data indicate that from 2021 through 2023—when local jurisdictions submitted the majority of their draft housing elements for the sixth cycle—HCD’s turnover rate for reviewers ranged from 11 percent to 48 percent. This inconsistent turnover, driven in part by increased workload and housing element complexity, can strain HCD’s ability to provide sufficient support to local jurisdictions.

Although it has developed a comprehensive, multiphase training program for new housing element reviewers, HCD relies heavily on experienced secondary reviewers to ensure consistent feedback. Although the five reviewers we interviewed reported having completed the initial training phase, four of them did not participate in the cohort training that HCD identifies as the second phase. HCD indicated that all new housing element reviewers are, at minimum, expected to watch the training videos—phase one of initial training—and to receive training with their supervisors before beginning to conduct reviews. HCD requires that a secondary reviewer review all findings letters before they are sent to their respective jurisdictions, which helps ensure consistency in its findings letters, including those written by primary reviewers who have not completed cohort training before they begin performing reviews.

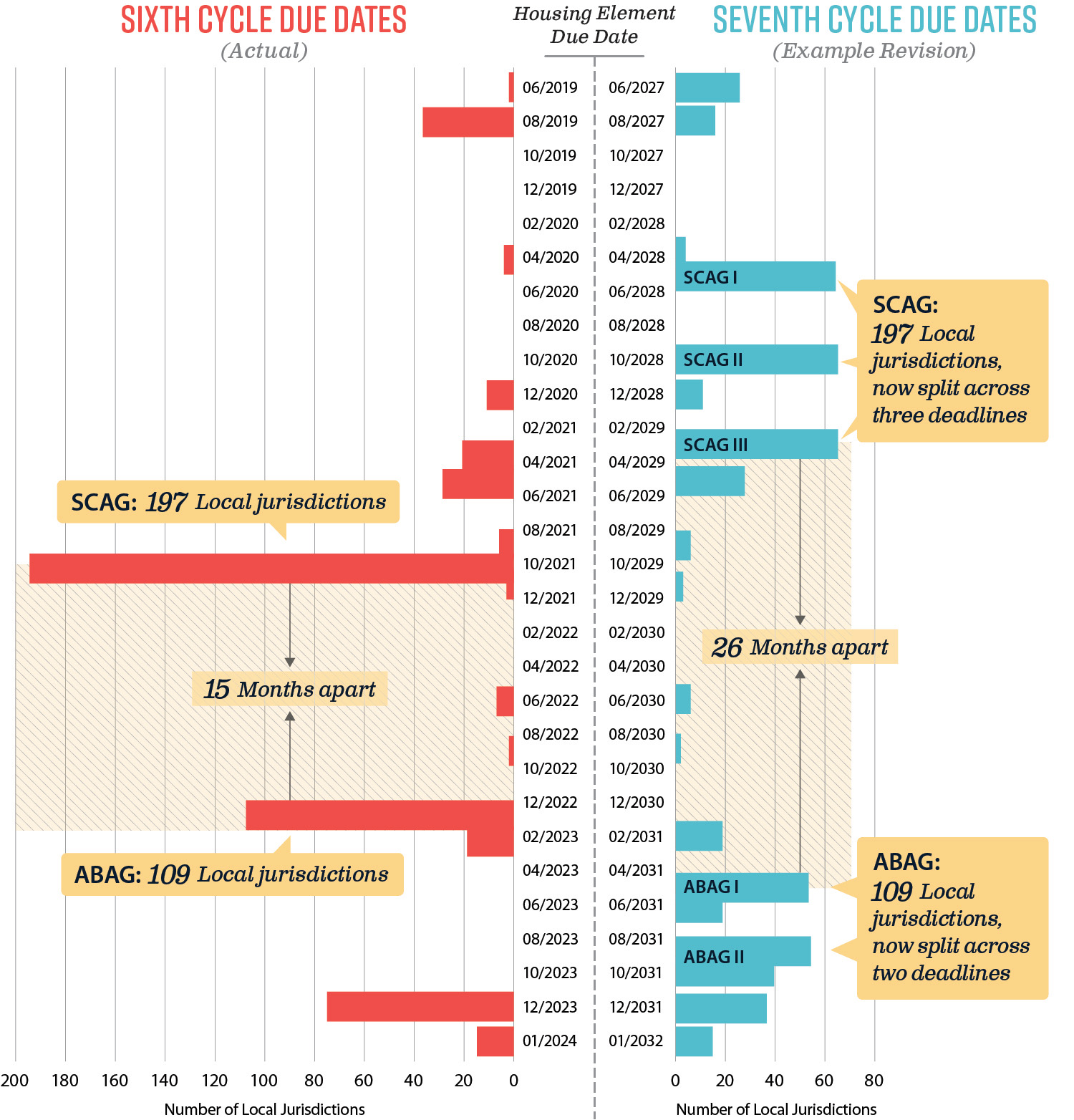

To address these findings, we have made recommendations to the Legislature to better stagger the deadlines for jurisdictions to submit housing elements, reducing spikes in HCD’s workload so it is able to give local jurisdictions the individualized assistance they need. We also recommended that HCD develop or revise its policies to ensure that it offers regularly scheduled meetings to local jurisdictions after they have received findings letters and that it publishes guidance in a timely manner.

Agency Comments

HCD agreed with our recommendations but indicated that it would only be feasible to provide guidance on new laws before they take effect if the Legislature implements our recommendation to include a transition period for new housing element law—such as delaying the effective date of a law enacted during a planning cycle.

Introduction

Background

In a 2016 report1, California ranked 49th out of 50 states in housing units per capita. The report further estimated that the State was losing $140 billion per year in output from missing construction investment and other missing consumption because of its housing shortage. The State’s shortage of housing has had significant consequences for residents of California. As Figure 1 shows, this housing crisis has contributed to Californians’ growing financial vulnerability, has increased homelessness, and has led some individuals to leave the State.

Figure 1

California’s Housing Crisis Has Widespread Consequences

Source: HCD, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Public Policy Institute of California.

Figure 1 is a graphic with three sections depicting the consequences of California’s housing crisis: homelessness, financial vulnerability, and departure from the State. The first section discusses homelessness and indicates that, in 2023, an estimated 28 percent of all people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. and 49 percent of the nation’s unsheltered population lived in California. The second section indicates that the majority of Californian renters—more than 3 million households—pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, and nearly one-third—more than 1.5 million households—pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent. Finally, the third section discusses departure from the State and indicates that housing has become a major reason Californians the State. The third section states that housing has become a major reason Californians leave the state; that approximately 34 percent of Californians responding to a survey indicated they have seriously considered leaving the State because of high housing costs.

To address these ongoing problems, the Legislature passed the Housing Crisis Act of 2019, declaring that the State is experiencing a housing supply crisis. The act asserted that the State needed an estimated 180,000 new homes each year to keep up with population growth. However, the State has fallen short of the Legislature’s estimated need for new housing construction. HCD reported that from 2019 through 2024, local jurisdictions issued permits for a total of only about 754,000 new units, or about 126,000 new units per year. Of these permitted homes, about 571,000 homes were built, or approximately 95,100 per year.

Since 1969, the State has required that all local jurisdictions work to meet the housing needs of their community members. Local jurisdictions accomplish this goal by adopting and periodically revising housing plans—also known as housing elements—as part of their general plan. The general plan is a local jurisdiction’s state-mandated plan that serves as a local jurisdiction’s blueprint for how it intends to grow and develop; in addition to housing, it also addresses issues such as transportation, land use, and safety. Specifically, cities’ housing elements focus on areas within city limits and counties’ housing elements focus on the unincorporated areas in the county. The text box shows key components of housing elements.

Key Components of Housing Elements

- Identification and analysis of existing and projected housing needs.

- Statement of goals, policies, quantified objectives, financial resources, and scheduled programs for the preservation, improvement, and development of housing.

- Identification of adequate sites for housing.

- Plan for the existing and projected needs of all economic segments of the community.

Source: State law.

History of Housing Element Updates

State law requires local jurisdictions to make periodic revisions to their housing elements. With few exceptions, the law sets deadlines for local jurisdictions that depend on the region in which the local jurisdiction lies. Voluntary organizations of local governments within a region are called Councils of Governments (COG)—a single or multicounty council created by a joint powers agreement under state statute. Following the 2008 enactment of Senate Bill (SB) 375—which sought to reduce statewide greenhouse gas emissions by integrating transportation, land use, and housing planning—housing element update cycles have been linked to each COG’s periodic, federally-mandated updates to their regional transportation plans. According to HCD, most major COGs currently follow eight-year update cycles, although some still use five-year cycles. Housing elements for the sixth cycle were due starting in June 2019, with the last local jurisdictions having due dates in January 2024. The earliest due dates for the seventh cycle were in June 2024.

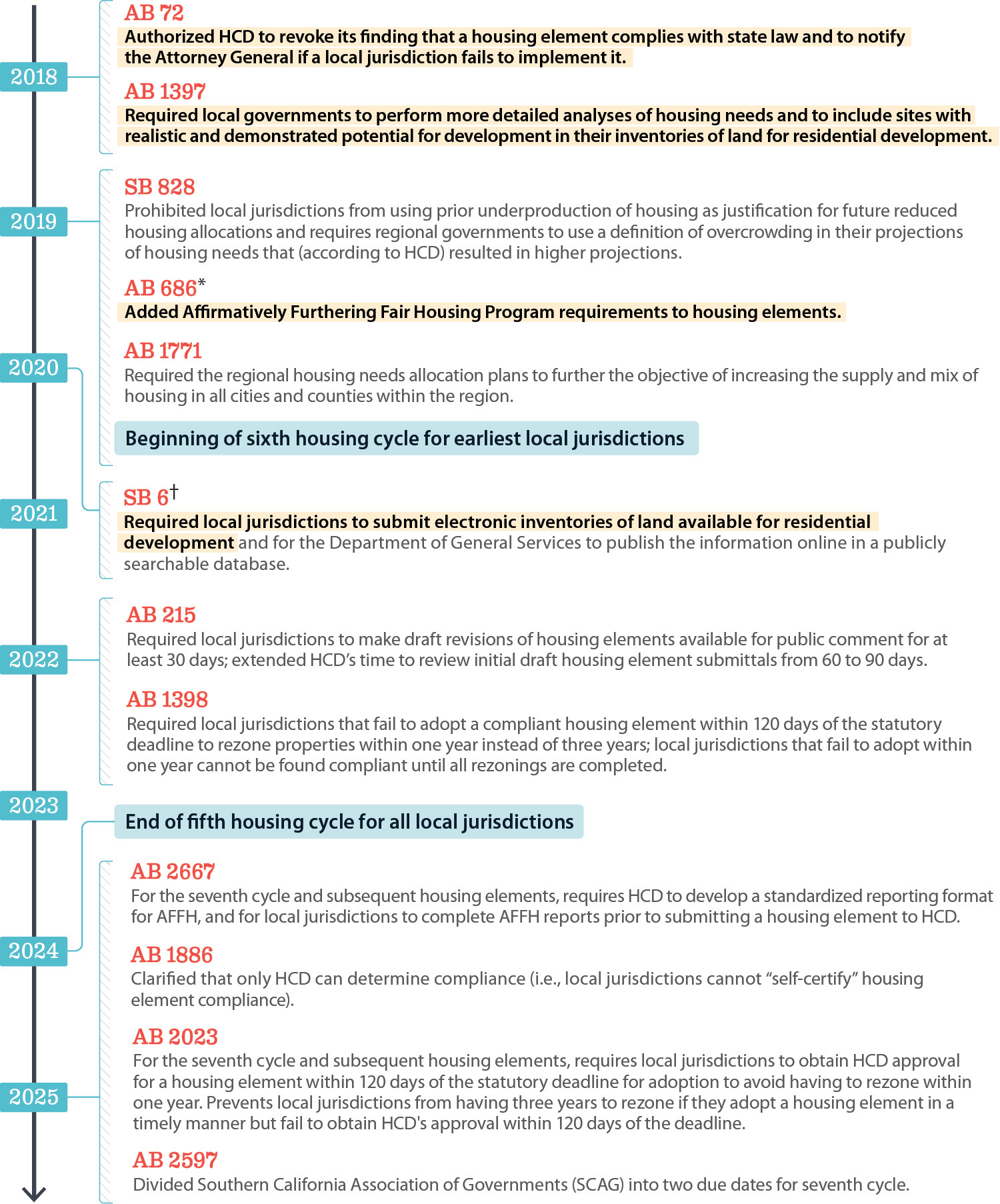

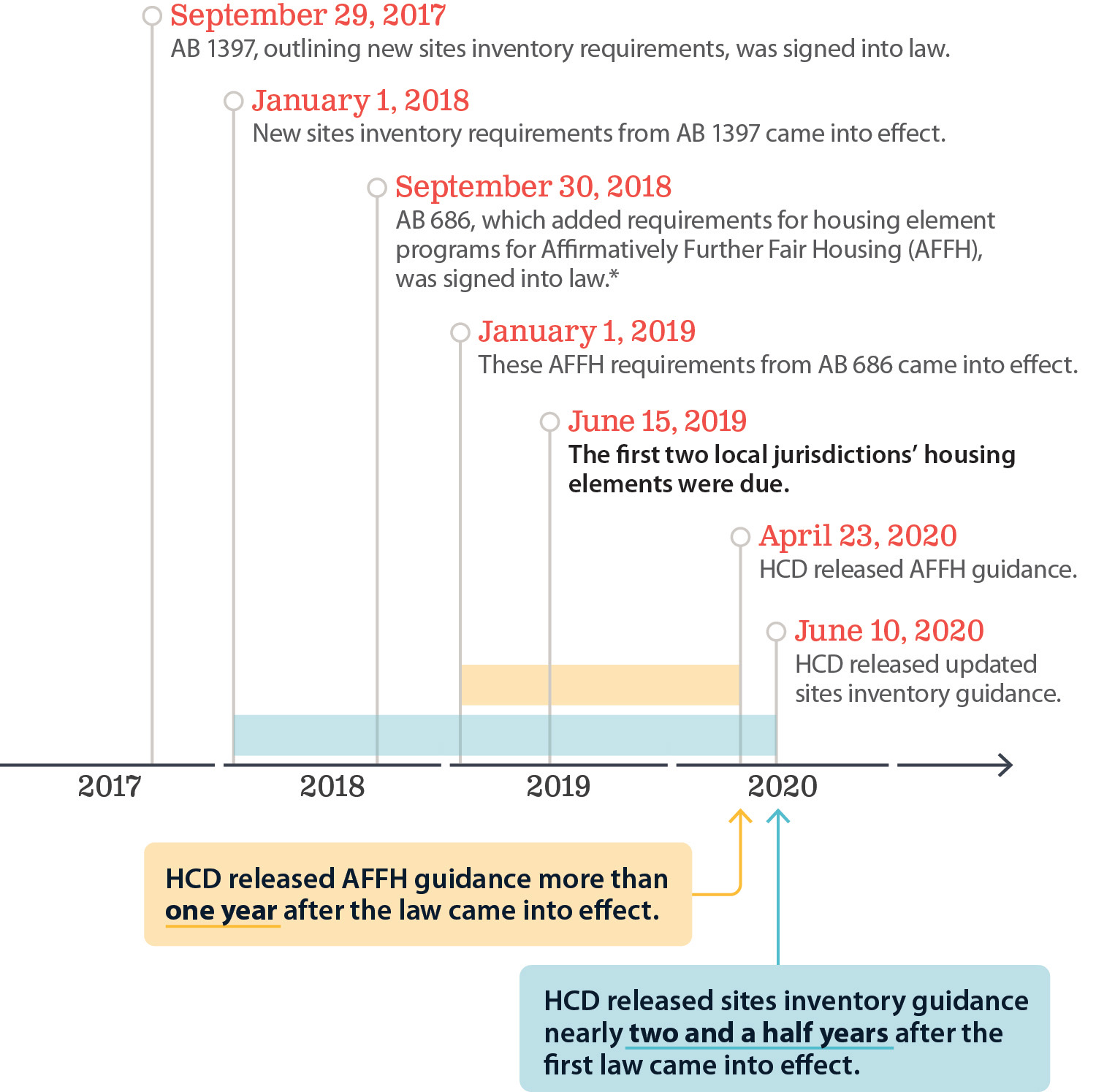

As Figure 2 shows, the Legislature passed a number of significant changes in law that affected the content of housing element updates for the sixth cycle. For example, state law requires local jurisdictions whose housing element updates were due on or after January 1, 2021, to complete an Assessment of Fair Housing—an analysis that included a summary of the jurisdiction’s fair housing issues, integration and segregation patterns, and future fair housing priorities. We discuss the effect of these changes on the local jurisdictions’ housing element updates in the Audit Results.

Figure 2

The Legislature Made Significant Changes to the Housing Element Law for the Sixth Cycle

Source: State law and HCD documentation.

Note: Dates listed reflect the year each law became effective. Unless stated otherwise, laws became effective on January 1 of the listed year.

* AB 686 also required all local jurisdictions whose housing elements were due on or after January 1, 2021, to conduct an Assessment of Fair Housing as part of their housing element submittals.

† SB 6 came into effect on January 1, 2020, but the specific requirement for electronic submittals of sites inventory did not come into effect until January 1, 2021.

Figure 2 is a vertically oriented timeline that depicts major changes made to housing element law from 2018 to 2025. For 2018, the timeline lists two changes: AB 72, which authorized HCD to revoke its finding that a housing element complies with state law and to notify the Attorney General if a local jurisdiction fails to implement it; and AB 1397, which required local governments to perform more detailed analyses of housing needs and to include sites with realistic and demonstrated potential for development in their inventories of land for residential development. The timeline highlights both AB 72 and AB 1397 as particularly significant changes to housing element law.

For 2019, the timeline lists three changes: SB 828, which prohibited local jurisdictions from using prior underproduction of housing as justification for future reduced housing allocations and required regional governments to use a definition of overcrowding in their projections of housing needs that (according to HCD) resulted in higher projections; AB 686, which added Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Program requirements to housing elements; AB 1771, which required the regional housing need allocation plans to further the objective of increasing the supply and mix of housing in all cities and counties within the region. The timeline highlights AB 686 as a particularly significant change, and notes that 2019 also marked the beginning of the 6th housing cycle for the earliest local jurisdictions.

For 2020, the timeline lists one major change: SB 6, which required local jurisdictions to submit electronic inventories of land available for residential development and for the Department of General Services to publish the information online in a publicly searchable database.

For 2021, the timeline lists no changes.

For 2022, the timeline lists two changes: AB 215, which required local jurisdictions to make draft revisions of housing elements available for public comment for at least 30 days and extended HCD’s time to review initial draft housing elements from 60 to 90 days; and AB 1398, which required local jurisdictions that fail to adopt a compliant housing element within 120 days of the statutory deadline to rezone properties within one year instead of three years. The timeline further notes under AB 1398 that jurisdictions that fail to adopt within one year cannot be found compliant until all rezonings are completed.

For 2023, the timeline lists no changes.

For 2024, the timeline lists no changes, but indicates that 2024 marked the end of the fifth housing cycle for all local jurisdictions.

For 2025, the timeline lists four changes: AB 2667, which, for the seventh cycle and subsequent housing elements, requires HCD to develop a standardized reporting format for AFFH, and for local jurisdictions to complete AFFH reports before prior to submitting their housing elements to HCD; AB 1886, which clarified that only HCD can determine compliance (i.e. that local jurisdictions cannot “self-certify” housing element compliance); AB 2023, which, for the seventh cycle and subsequent housing elements, requires local jurisdictions to obtain HCD approval for a housing element within 120 days of the statutory deadline for adoption to avoid having to rezone within one year and prevents local jurisdictions from having three years to rezone if they adopt a housing element timeline but fail to obtain HCD’s approval within 120 days of the deadline; and AB 2597, which divided the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) into two due dates for the seventh cycle.

Finally, the Governor vetoed Assembly Bill (AB) 650 in October 2025, which would have—among other things—required HCD to provide local jurisdictions with specific analysis or text to remedy each identified deficiency in a findings letter. In a notification to members of the California State Assembly about why he did not sign the bill, the Governor stated that the bill would inappropriately shift responsibility for preparing housing elements from local jurisdictions to HCD and indicated that the fundamental responsibility of planning for housing needs falls on local governments.

HCD’s Responsibilities Related to Housing Elements

As the department primarily responsible for California’s housing policy, HCD has a number of significant responsibilities related to the local jurisdictions’ development of their housing elements. Most critically, it is responsible for assigning new housing units to COGs through the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (housing needs allocation) process, determining whether each local jurisdiction’s revised housing element complies with state law, and addressing local jurisdictions’ violations related to their housing elements.

Housing Needs Allocation Process

In consultation with each COG, HCD determines how much housing at a variety of affordability levels is necessary in each region of the State and assigns a number of new units to each COG as part of the housing needs allocation process. These units encompass housing at all income levels. Using their own methodologies, each COG subsequently allocates those projected housing units among their member local jurisdictions. Finally, local jurisdictions plan for how to meet their allocated housing need in their housing element updates.2

HCD explained that in the fifth housing element cycle, which began in 2013, allocations for new housing units tended to be lower, according to HCD, because of a downturn in the housing market. In contrast, the housing needs allocations process for the sixth cycle resulted in significantly higher allocations for several jurisdictions. In fact, some jurisdictions had their allocations triple. Beverly Hills—one of the 10 jurisdictions we selected for our review—saw its allocation increase from three housing units for the fifth cycle to 3,104 for the sixth cycle.

The Housing Element Review Process

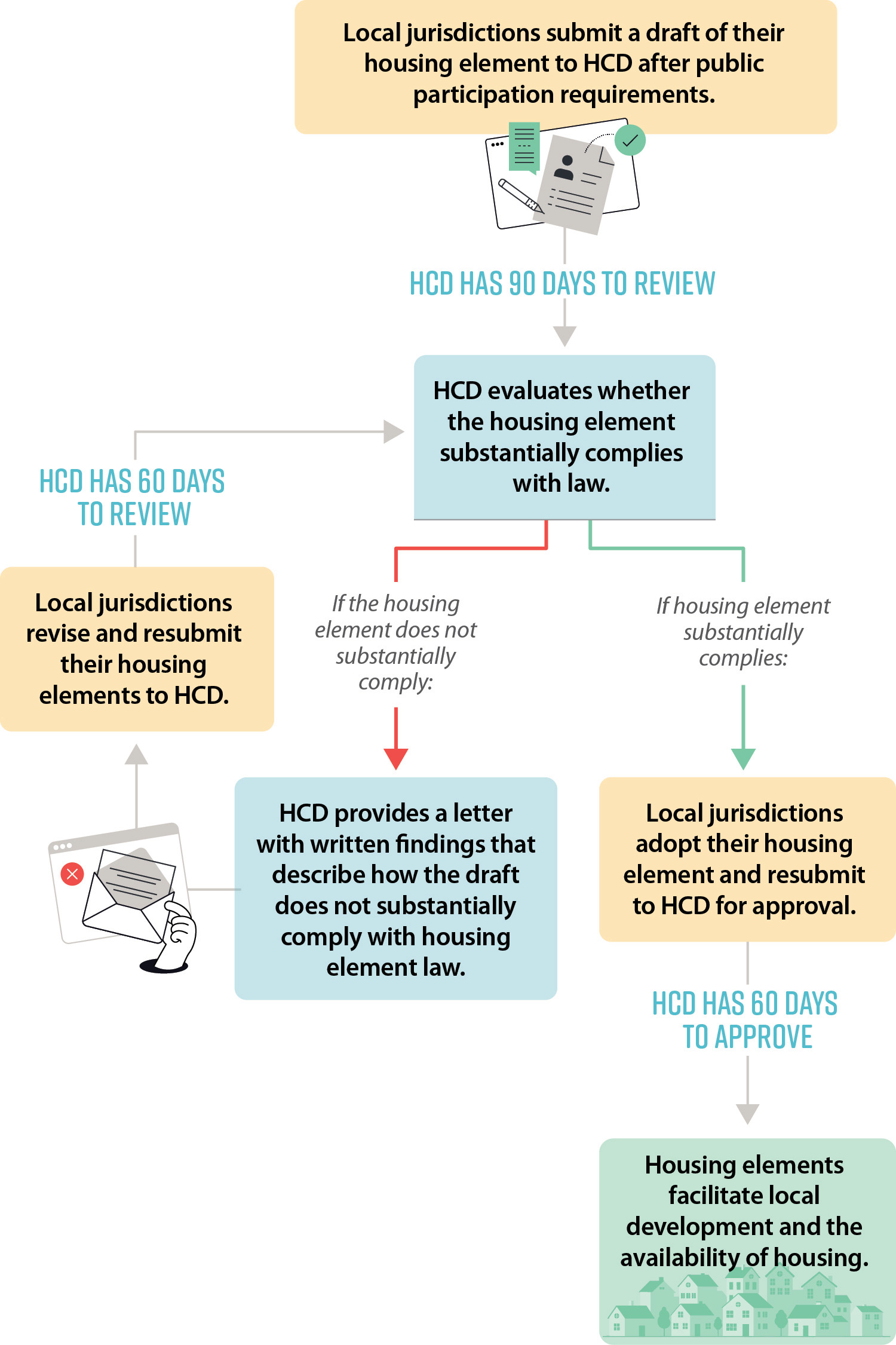

State law requires HCD to review local jurisdictions’ housing elements, determine whether they substantially comply with state law, and report its written findings to the local jurisdiction. We refer to HCD’s determination that a revised housing element substantially complies with state law as approving the housing element. Figure 3 illustrates the housing element review process. Housing element law establishes that HCD has 90 days after a local jurisdiction’s first submission and 60 days after subsequent submissions to complete its review. It does not establish how quickly local jurisdictions must resubmit after receiving HCD’s findings letters.

Figure 3

The Housing Element Approval Process Requires Involvement From Local Jurisdictions, HCD, and the Public

Source: State law.

Figure 3 is a flowchart that describes the housing element approval process and the roles of various local and State agencies in the process. The flowchart indicates that the process begins when local jurisdictions submit a draft of their housing element to HCD after public participation requirements. Once this occurs, HCD has 90 days to review. Then, the chart indicates that HCD evaluates whether the housing element substantially complies with law, indicating two potential options: the housing element does not substantially comply, or the housing element substantially complies.

If the housing element does not substantially comply, HCD provides a letter with written findings that describe how the draft does not substantially comply with housing element law. Local jurisdictions, upon receipt of this letter, revise and resubmit their housing elements to HCD. HCD then has 60 days to review, and the graphic indicates that we return to the step where HCD evaluates whether the housing element substantially complies with law. If the housing element substantially complies, local jurisdictions adopt their housing element and resubmit to HCD for approval. HCD then has 60 days to approve, and the final step indicates that housing elements facilitate local development and the availability of housing.

HCD reports its determination of whether a draft housing element substantially complies with state law in a findings letter. In this letter, HCD identifies any requirements that the housing element did not meet. It typically includes a citation to the relevant section of state law, an explanation of the requirements of that section, and some additional examples and suggestions for how the local jurisdiction might meet the requirements. As part of its review of housing elements, state law requires HCD to consider public comments from any public agency, group, or person.

State law also authorizes HCD to provide guidance to local jurisdictions regarding the updating of their housing elements but establishes that this guidance is advisory. HCD currently provides such guidance through online resources and tools, webinars and presentations, and direct, individualized assistance. We discuss HCD’s guidance in more detail later in the report.

HCD’s Enforcement Authority

Changes in law in 2017 expanded HCD’s enforcement authority over the housing element law and the implementation of housing elements. These changes allow HCD to review any action a jurisdiction takes that is inconsistent with its housing element. After HCD identifies an issue, it first attempts to work with the local jurisdiction to implement a remedy. If the potential violation is not resolved, it then gives the local jurisdiction 30 days to take appropriate action. If the local jurisdiction continues to fail to correct the issue, HCD is authorized to revoke its finding that a housing element is compliant and to refer the issue to the attorney general. There are several consequences to having a housing element that is out of compliance, including legal challenges, condensed rezoning, potential funding losses, and the builder’s remedy—a provision of state law that allows developers to bypass certain local zoning rules. We discuss these consequences in further detail later in the report. HCD’s enforcement authority helps to ensure that jurisdictions appropriately adopt and implement the programs in their housing elements.

Our Selection of Local Jurisdictions

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed us to select and review 10 of the State’s 539 local jurisdictions according to their population, geography, and compliance with HCD’s standards. The Audit Committee asked us to assess HCD’s responsiveness in reviewing these 10 local jurisdictions’ housing elements during the fifth and sixth cycles, to evaluate HCD’s comments and feedback during the sixth cycle, and to determine the number of reviewers that worked on HCD’s housing element reviews.

In making our selection, we considered the characteristics that the Audit Committee had identified, as well as the number of sixth-cycle draft housing elements the local jurisdictions submitted to HCD, the duration of their sixth-cycle review process, and any differences from the fifth to the sixth cycle in their number of drafts and the length of their review process. We generally selected local jurisdictions that took longer than typical to complete the process, and our selection does not reflect local jurisdictions’ typical experiences with the review process.

According to these considerations, we selected the 10 local jurisdictions listed in the text box. The local jurisdictions are located in 10 different counties and have populations that range from about 4,000 to 440,000. Some were in compliance with housing element law during our audit, and others were not. Some submitted a low number of draft housing elements, and others submitted a high number of drafts. The duration of each of their reviews also differed.

Ten Selected Local Jurisdictions

- Anaheim

- Beverly Hills

- Canyon Lake

- Clovis

- Del Mar

- Eureka

- Oakland

- Rialto

- Santa Barbara

- Saratoga

Source: Auditor analysis.

Audit Results

For Most Local Jurisdictions, the Housing Element Approval Process for the Sixth Cycle Was Longer Than for the Fifth Cycle

The local jurisdictions’ timely adoption and implementation of their housing element updates is critical to meeting the State’s goal of increasing the housing supply. As we discuss in the Introduction, state law requires local jurisdictions to revise and adopt a compliant housing element at least every eight years, although the exact dates by which the local jurisdictions must adopt their plans vary, based on their Council of Governments (COG). For example, jurisdictions within the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), a COG with 197 member jurisdictions, were required to adopt their sixth-cycle housing elements by October 15, 2021, but the deadline for the 109 member jurisdictions of the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) was January 31, 2023.

Jurisdictions that fail to adopt a compliant housing element timely face several possible consequences, including ineligibility for state funding. We describe these consequences in more detail later in the report. On average, local jurisdictions submitted their initial draft housing element for the sixth cycle to the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) just 23 days before the statutory deadline. Although state law allows HCD up to 90 days to review the initial drafts, fewer than 40 percent of local jurisdictions submitted these drafts at least 90 days in advance. Additionally, 30 percent of local jurisdictions submitted their initial draft after the deadline had already passed.3

Overall, local jurisdictions’ housing element review process for the sixth cycle was significantly longer than it was for the fifth cycle. As Table 1 shows, as of November 2024, the median review process time was 387 days—or more than one year—in the sixth cycle.4 In contrast, the median length of the review process in the fifth cycle was 171 days, less than half as long.

More than half of this increase in the length of the review process is attributable to the time the local jurisdictions spent revising their plans, in large part caused by new requirements in state law, which we discuss in the next section. Housing element law requires HCD to complete its review of initial drafts within 90 days and subsequent drafts within 60 days. It does not establish any similar requirements related to how quickly local jurisdictions must respond after receiving HCD’s findings letters, which summarize the results of the department’s reviews. As Table 1 shows, HCD spent a median of 177 cumulative days completing its review of all drafts submitted, whereas local jurisdictions spent a median of 210 cumulative days with the drafts between HCD’s review periods. When we reviewed all 51 sixth-cycle housing elements that the 10 selected local jurisdictions submitted, we found that HCD met its statutory deadlines in each instance.

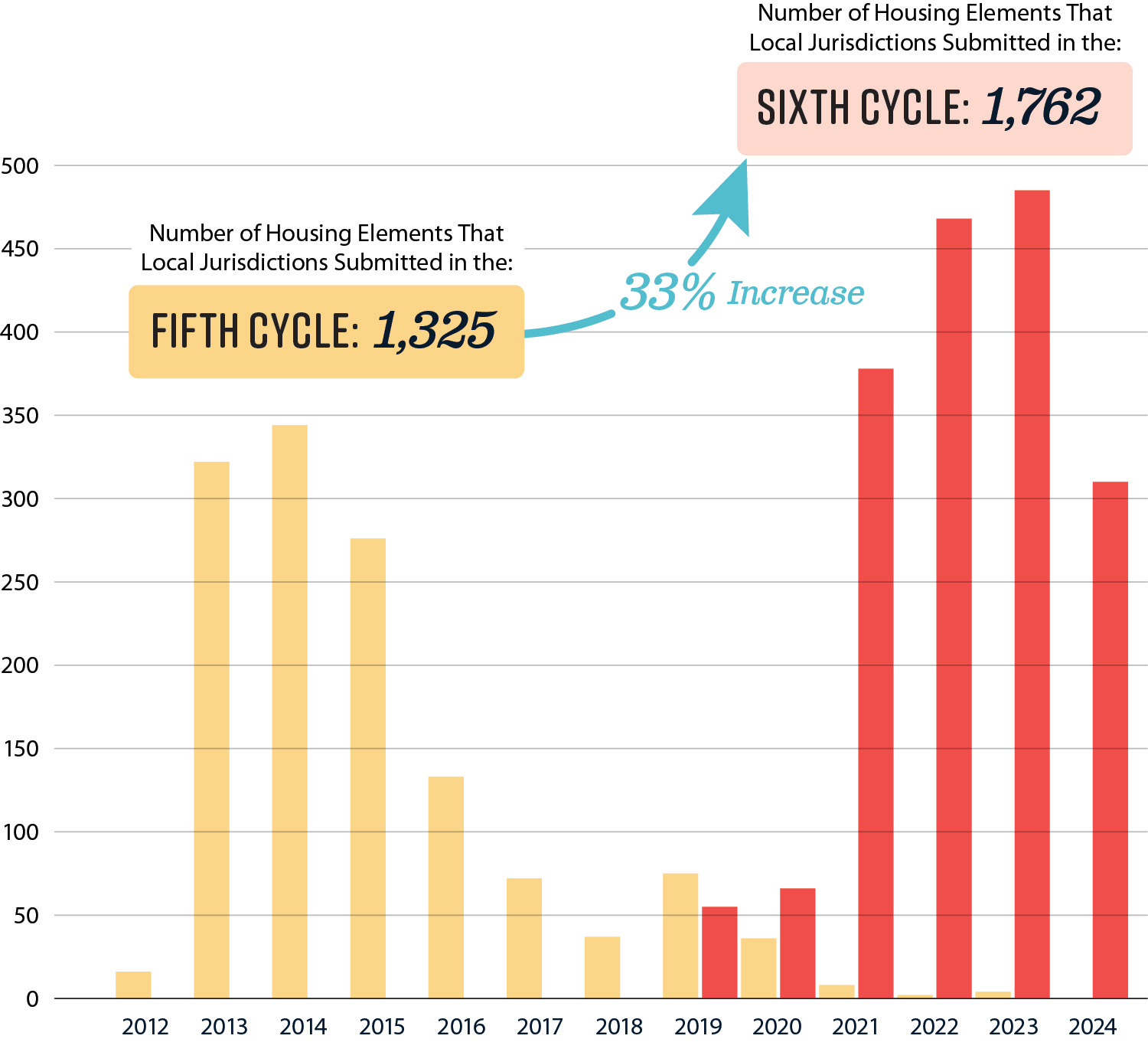

Both the median and the total number of drafts that local jurisdictions submitted to HCD for review also increased from the fifth to the sixth cycle. The total number of drafts these jurisdictions submitted to HCD rose from approximately 1,300 to nearly 1,800, and the median number of drafts grew from two to three submissions. According to HCD, it generally anticipates local jurisdictions will submit at least three draft housing elements: two drafts prior to the jurisdiction adopting it, and after HCD’s review, a third draft adopted by the local jurisdiction for HCD’s final determination. HCD also noted that it had anticipated that the number of draft housing elements would increase in the sixth cycle because of the new laws that introduced new complexity into the requirements for compliance. As Table 2 shows, 427 jurisdictions, or 81 percent, achieved a compliant, adopted housing element within two or fewer drafts in the fifth cycle compared to only 92 jurisdictions, or 22 percent of the jurisdictions that achieved a compliant, adopted housing element in the sixth cycle. However, across both cycles, most of the local jurisdictions that achieved a compliant, adopted housing element did so within three or fewer drafts: 93 percent for the fifth cycle and 55 percent for the sixth cycle.

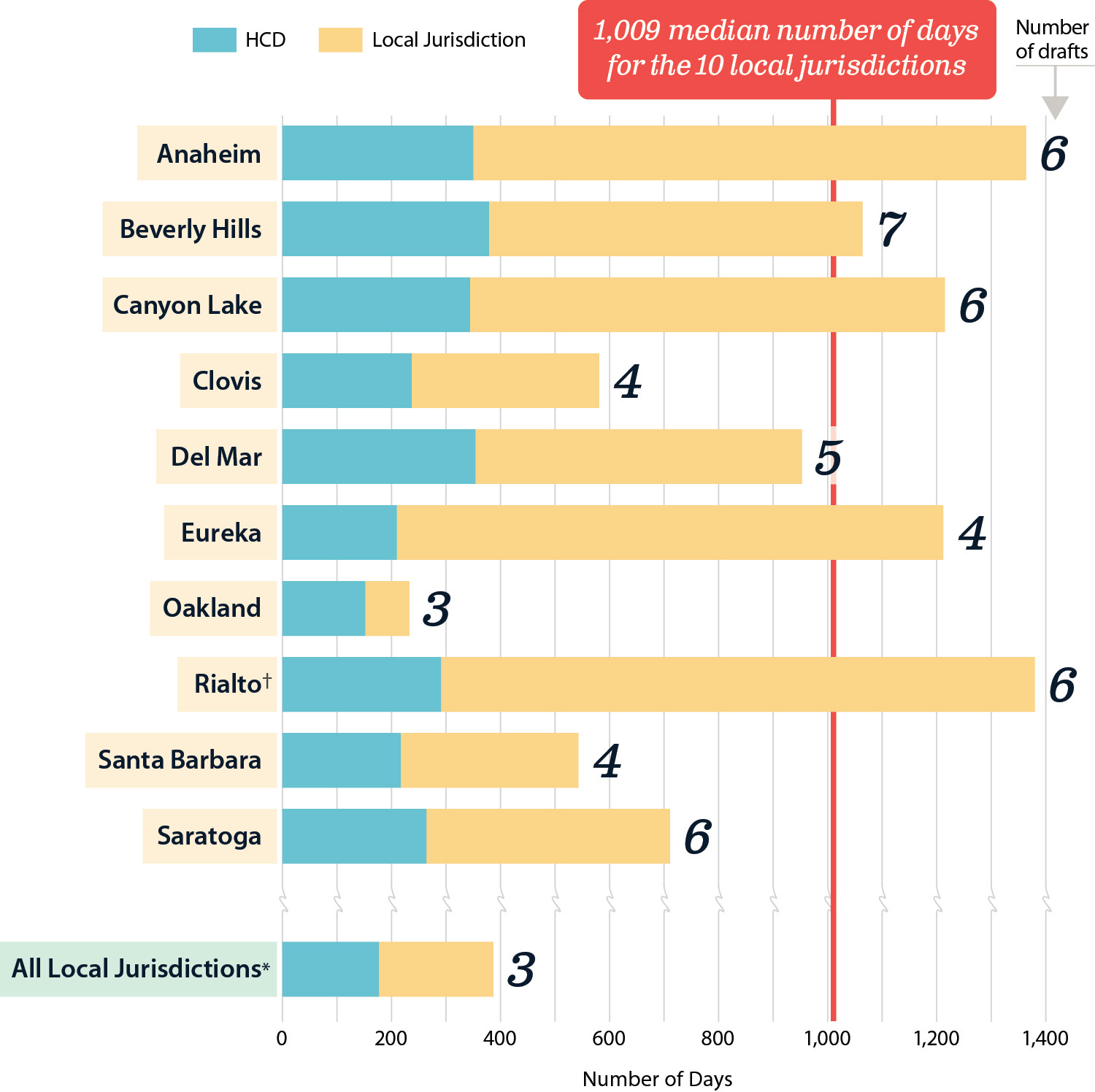

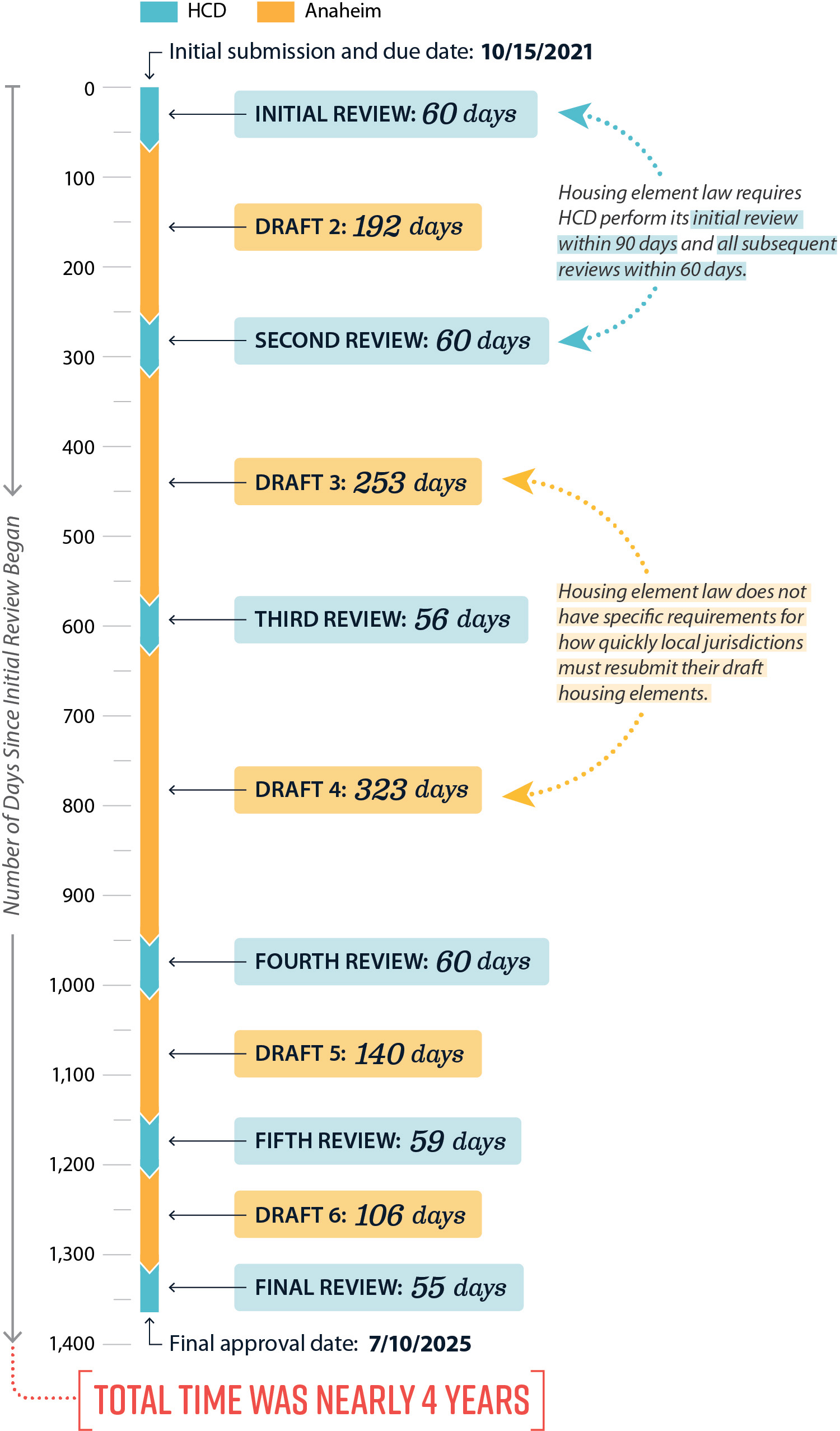

The median sixth-cycle review process for the 10 local jurisdictions we selected was significantly longer than the median for all local jurisdictions, largely because of the time the local jurisdictions spent revising their drafts between HCD’s reviews. As Figure 4 shows, the process for these 10 jurisdictions took a median of 1,009 days, or 2.8 years,5 and they submitted a median of 5.5 drafts. HCD reviews accounted for 30 percent of that time, and local jurisdictions accounted for the remaining 70 percent. For example, Anaheim was responsible for nearly three-quarters of the total time to complete the housing element, as Figure 5 shows. According to Anaheim, these delays were due in part to the new complex analyses required for the sixth cycle, and in part to the fact that the city was involved in a lawsuit with HCD unrelated to housing elements.

Figure 4

The 10 Local Jurisdictions We Reviewed Took a Median of Nearly Three Years to Complete an Approved Housing Element

Source: HCD documentation and auditor analysis of HCD’s housing element tracking system data as of November 2024.

*The median number of days and drafts for all local jurisdictions is as of November 2024 and includes local jurisdictions that had not yet completed their approved housing element as of November 2024.

† As of November 2025, Rialto was not yet in compliance with a completed and adopted housing element.

Figure 4 is a horizontal bar chart depicting the number of days each jurisdiction took to complete an approved housing element and the number of drafts each jurisdiction completed. The jurisdictions are listed vertically along the vertical axis in descending alphabetical order, beginning with Anaheim at the top and Saratoga at the bottom, with an additional item at the bottom listing the median number of days and drafts for all local jurisdictions within the State. Each of the ten jurisdictions is depicted with a bar to its right, with a blue shaded component that depicts the amount of time HCD spent reviewing the draft and the amount of time the jurisdiction spent revising it.

First, the chart lists Anaheim, which submitted six drafts over the course of approximately 1,350 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 350 days, and Anaheim was responsible for the rest.

Second, the chart lists Beverly Hills, which submitted seven drafts over the course of approximately 1,050 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 375 days, and Beverly Hills was responsible for the rest.

Third, the chart lists Canyon Lake, which submitted six drafts over the course of approximately 1,200 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 350 days, and Canyon Lake was responsible for the rest.

Fourth, the chart lists Clovis, which submitted four drafts over the course of approximately 600 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 250 days, and Clovis was responsible for the rest.

Fifth, the chart lists Del Mar, which submitted five drafts over the course of approximately 950 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 350 days, and Del Mar was responsible for the rest.

Sixth, the chart lists Eureka, which submitted four drafts over the course of approximately 1200 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 200 days, and Eureka was responsible for the rest.

Seventh, the chart lists Oakland, which submitted three drafts over the course of approximately 225 days. HCD was responsible for roughly 150 days, and Oakland was responsible for the rest.

Eighth, the chart lists Rialto, which submitted six drafts over the course of approximately 1,400 days. HCD was responsible for approximately 300 days, and Rialto was responsible for the rest. The chart additionally notes that, as of November 2025, Rialto was not yet in compliance with an adopted housing element.

Ninth, the chart lists Santa Barbara, which submitted four drafts over the course of approximately 425 days. HCD was responsible for approximately 200 days, and Santa Barbara was responsible for the rest.

Tenth, the chart lists Saratoga, which submitted six drafts over the course of approximately 700 days. HCD was responsible for approximately 250 days, and Saratoga was responsible for the rest.

Finally, the chart includes a bar indicating the median number of days and drafts for all local jurisdictions—including those that had not yet completed their approved housing element—as of November 2024. All local jurisdictions submitted a median of 3 drafts over the course of approximately 375 days. HCD was responsible for approximately 175 days, and the local jurisdictions were responsible for the rest. To the right of each bar, the chart lists the number of drafts each jurisdiction submitted. Finally, the chart includes a vertical line indicating the median number of days—1,001 days—the 10 local jurisdictions we reviewed took to complete an approved housing element; the statewide median depicted at the bottom is slightly below 500 days.

Figure 5

Anaheim Accounted for 74 Percent of the Total Time Spent Completing Its Housing Element

Source: HCD documentation.

Figure 5 is a modified vertical timeline depicting the total amount of time Anaheim took to complete its housing element. The timeline indicates that, in total, Anaheim submitted six drafts before receiving its final approval on July 10, 2025—a process which took nearly four years—and accounted for 74 percent of the total time spent completing its housing element.

The timeline is composed of alternating blue and yellow segments representing the number of days HCD and Anaheim took spent on the housing element, respectively. To the left, the timeline lists a series of numbers indicating the number of days since HCD’s initial review began. The timeline begins with HCD’s initial review of Anaheim’s draft housing element, which took HCD 60 days to complete after Anaheim submitted its housing element draft on October 15, 2021. Next, Anaheim took 192 days to complete its second draft, and HCD took 60 days to complete its second review. The timeline additionally notes that housing element law requires HCD to perform its initial review within 90 days and all subsequent reviews within 60 days.

Next, Anaheim took 253 days to complete its third draft, and HCD took 56 days to complete its third review. To the right of these segments of the timeline, the graphic indicates that housing element law does not have specific requirements for how quickly local jurisdictions must resubmit their draft housing elements after HCD has completed its review.

Next, Anaheim took 323 days to complete its fourth draft, and HCD took 60 days to complete its review. For its fifth draft, Anaheim took 140 days, and HCD took 59 days to review., For its sixth and final draft, Anaheim took 106 days, and HCD took 55 days in its final review. Anaheim’s final approval date was July 10, 2025, nearly four years after it submitted its first draft. The timeline also indicates that HCD never spent more than 60 days reviewing Anaheim’s draft housing element, indicating that HCD met all its statutory review deadlines.

Many Factors Contribute to the Length of the Housing Element Approval Process

Our conversations with local jurisdictions and HCD led us to identify multiple factors that contributed to the length of the housing element approval process, as Figure 6 shows. Although aspects of these factors may have been present in prior cycles, they collectively had a significant effect on the process in the sixth cycle.

Figure 6

Many Factors Contributed to the Length of the Sixth Cycle Approval Process

Source: State law, HCD documentation, interviews with local jurisdictions, and other documentation.

Figure 6 is an organization chart that depicts the various factors that contributed to the length of the sixth cycle approval process: new legal requirements; HCD’s role as defined in law; increased housing needs allocations; challenges with consultants; and community opposition to new housing. The chart contains five rows, each of which describes one of the previously-listed factors.

The factor described is new legal requirements. This row indicates new requirements in the housing element law such as Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing and major changes to the sites inventory required new and significant analyses by the local jurisdictions and increased the complexity of HCD’s reviews. The row also indicates that local jurisdictions reported that these changes made it more difficult to adopt a compliant housing element.

The second factor described is HCD’s role as defined in law. This row indicates that HCD generally may not require more than what is in law, limiting what it can prescribe in its finding letters. Further, the row states that while HCD provides its written determinations through findings letters, state law does not authorize HCD to change or enlarge statues.

The third factor described is increased housing needs allocations. This row indicates that the housing needs allocations during the sixth cycle increased dramatically, requiring local jurisdictions to plan for a much larger number of housing units.

The fourth factor described is challenges with consultants. This row indicates that some local jurisdictions that relied on consultants to assist with the housing element faced delays in the approval process due to factors such as difficulties in obtaining consultants or having new consultants go extensive evaluation of a local jurisdiction’s housing element. Finally, the fifth factor described is community opposition to the housing element. This row indicates that local jurisdictions and residents may resist developing new housing. The row further states that some local jurisdictions have attempted to amend the housing elements to reduce the amount of planned housing, and others have indicated that their communities are anti-development.

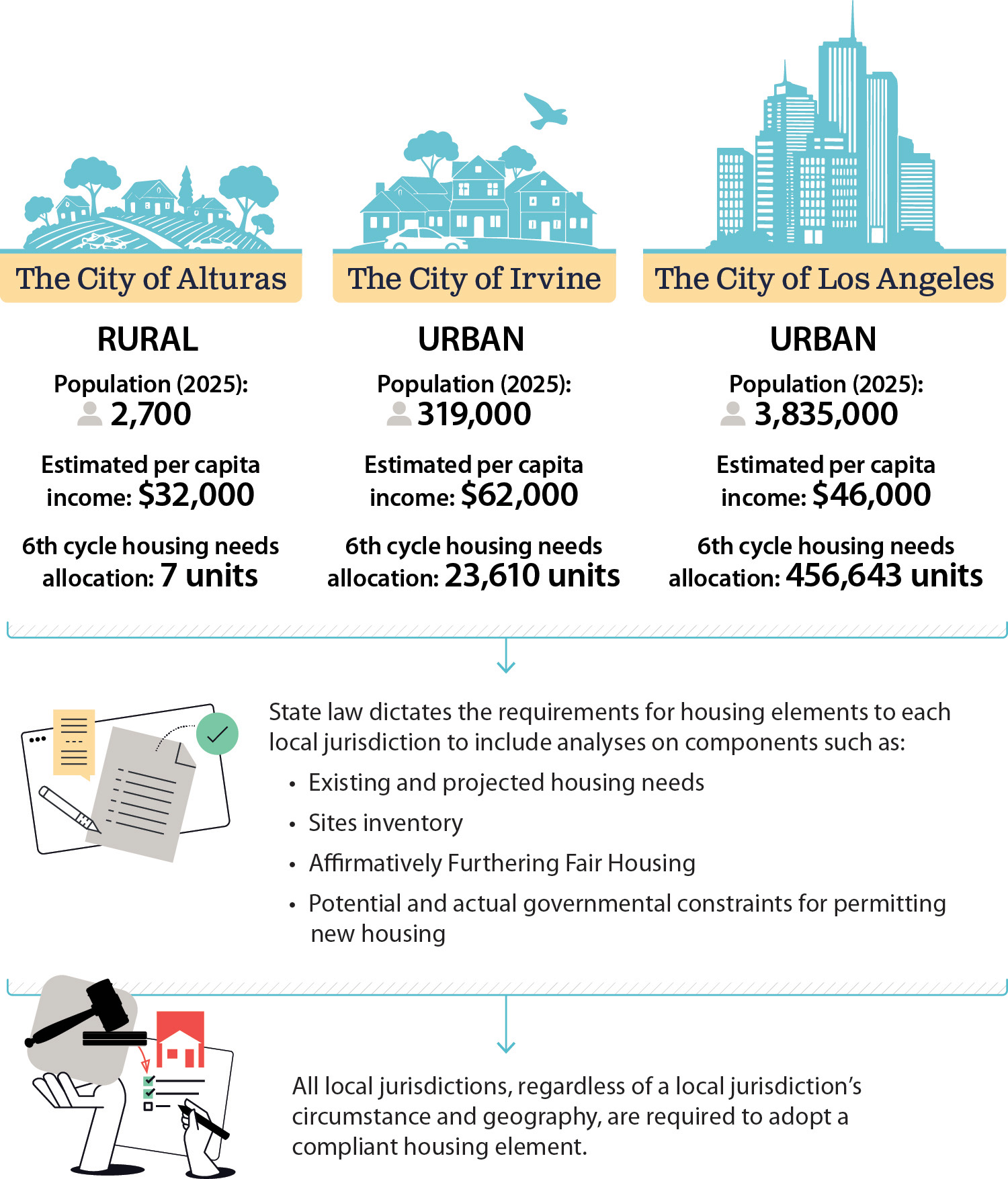

Housing element law provides broad requirements to maintain local discretion. Given its size, scope, and complexity, it is reasonable to conclude that the Legislature makes the housing element law provisions broad, which necessitates interpretations by HCD and an ongoing dialogue with local jurisdictions during the review process. Originally enacted in 1969 and amended dozens of times since, the housing element law spans nearly 50,000 words and accommodates the diverse needs of the 539 local jurisdictions across the state—each with its own geography, demographics, economic conditions, political climate, and resource constraints. The housing elements that local jurisdictions prepare are often extensive, frequently running hundreds of pages and sometimes exceeding a thousand. Courts have recognized that most statutes contain some degree of ambiguity. In fact, the Legislature purposefully makes some statutes broad as a tool to preserve flexibility in addressing unforeseen circumstances. Courts have affirmed that legislation does not need to achieve mathematical precision, nor must it anticipate every possible scenario to which it might apply. Importantly, the housing element law acknowledges that each local jurisdiction is best positioned to determine the specific actions it must take to contribute to the state’s housing goals. As HCD interprets and applies the law during its housing element review, it cannot dictate to local jurisdictions how they specifically choose to achieve compliance. As Figure 7 shows, the statute preserves room for local discretion while still providing a framework for statewide accountability. Additionally, as we note in a later section, according to HCD, it cannot dictate what local jurisdictions must do to achieve compliance because the local jurisdictions are the most knowledgeable about what housing plans work best for their community. Consequently, we concluded that the Legislature drafted the housing element requirements broadly to provide local discretion and to allow local jurisdictions to design programs that meet local needs while meeting state goals and targets. This dynamic of power sharing between the State and local jurisdictions—against the backdrop of a complex and broad legal framework—can create frustration among local jurisdictions as they seek to develop a housing element that HCD deems “compliant” or risk losing their control over local zoning rules.

Figure 7

All Local Jurisdictions in the State Must Adopt Compliant Housing Elements Regardless of Local Differences

Source: State law, HCD, and Department of Finance.

Figure 7 is a flow chart depicting how three very different jurisdictions—Alturas, Irvine, and Los Angeles—must all adopt compliant housing elements regardless of their local differences. The flowchart consists of three sections: the topmost section describes the differences between the three jurisdictions; the second section describes state law requirements for the content of housing elements; and the third section summarizes the requirement for all jurisdictions to adopt compliant housing elements.

The topmost section of the flowchart contains three columns depicting each jurisdiction’s differences. On the left, the chart describes the city of Alturas as a rural jurisdiction with a population of 2,700 as of 2025, an estimated per capita income of $32,000, and a sixth cycle housing allocation of seven units. In the middle, the chart describes the city of Irvine as an urban jurisdiction with a population of 319,000, an estimated per capita income of $62,000, and a sixth cycle housing allocation of 23,610. On the right, the chart describes the city of Los Angeles as an urban jurisdiction with a population of 3,835,000, an estimated per capita income of $46,000, and a sixth cycle housing allocation of 456,643 units. The top section ends with a modified funnel leading to the next section, indicating that all three jurisdictions—despite their differences—must follow state law requirements for their housing elements.

The middle section of the flowchart describes several state law requirements for housing elements. Specifically, the middle section shows that state law dictates the requirements for housing elements to each local jurisdiction to each local jurisdiction to include analyses on components such as:

Existing and projected housing needs

Sites inventory

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing

Potential and actual governmental constraints for permitting new housing.

The middle section also ends with a modified funnel leading to the next section. The final section of the chart states that all local jurisdictions, regardless of a local jurisdiction’s circumstance and geography, are required to adopt a compliant housing element.

New Legal Requirements

Two substantial changes in the housing element law took effect before the sixth cycle. First, in 2017, the Legislature amended the housing element law to add new sites inventory requirements that increased the complexity of jurisdictions’ analyses. This amendment included the requirement that local jurisdictions develop an inventory of land suitable and available for residential development, including both vacant sites and sites having realistic potential for redevelopment during the planning period. In 2019, the Legislature added to the requirement for nonvacant sites, stating that local jurisdictions are required to provide a description of the existing use of each property and, if owned by the jurisdiction, whether there are plans to dispose of—or to transfer the control or ownership of—the property during the planning period. As a result, during the sixth cycle, local jurisdictions needed to explain the methodology they used for determining the realistic build-out potential of the nonvacant sites within the planning period.

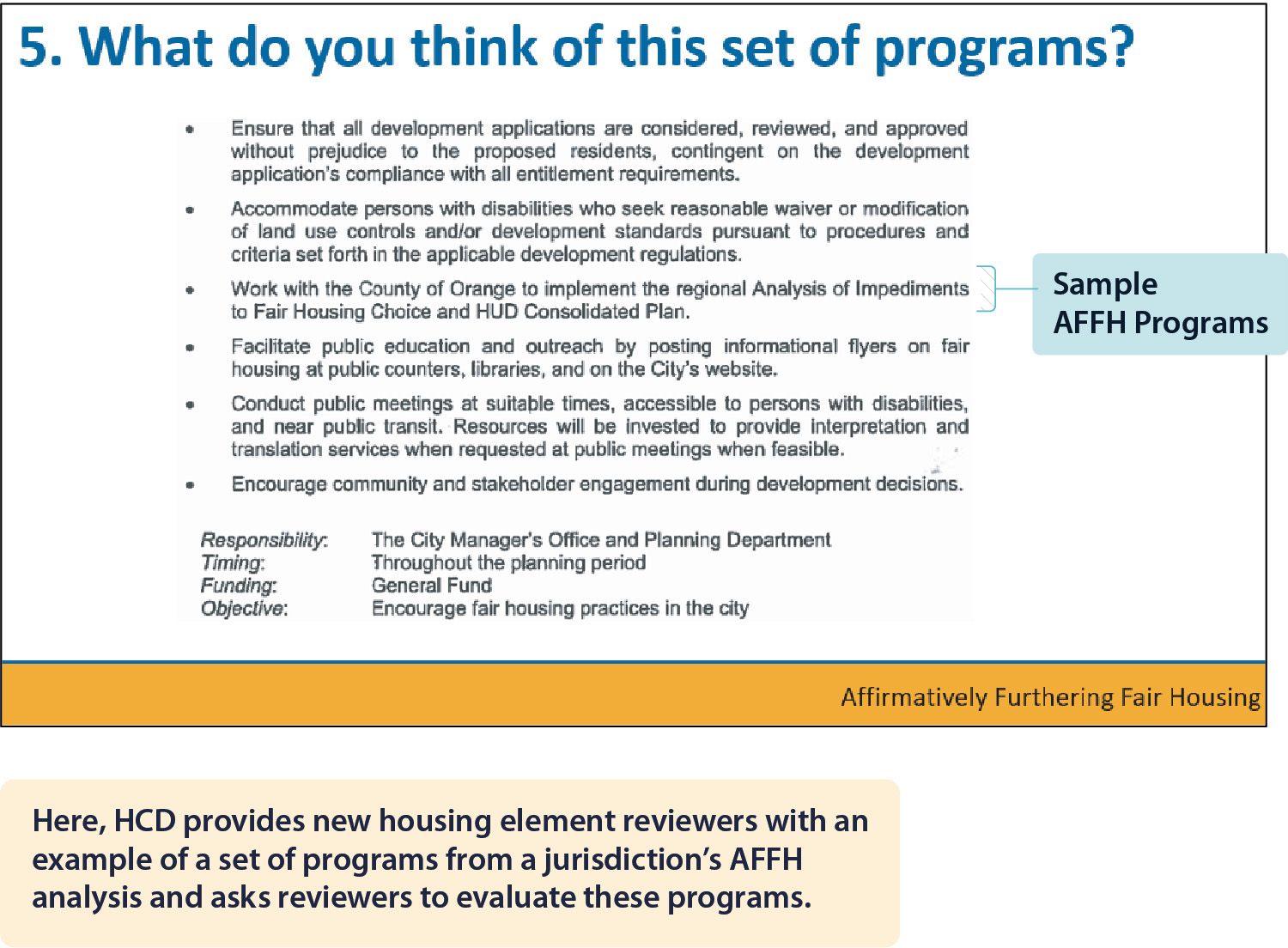

Second, in 2018, the Legislature added the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) requirements to ensure that programs and policies in the housing elements are consistent with the principles of affirmatively furthering fair housing. These principles involve taking meaningful actions to facilitate deliberate action to explicitly address, combat, and relieve disparities from past patterns of segregation to foster more inclusive communities. For instance, AFFH requires housing elements to include an analysis of available federal, state, and local data and knowledge to identify integration and segregation patterns and trends, racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty and affluence, disparities in access to opportunity, and disproportionate housing needs, including displacement risk.

All 10 of the local jurisdictions we interviewed stated that these changes in state law were significantly more challenging than the requirements from the fifth cycle and that these changes made it more difficult for them to adopt a compliant housing element during the sixth cycle. HCD acknowledged in its budget request to increase its staffing levels for the impending housing element workload that the changes in state law increased the complexity of housing elements. HCD explained that these changes constituted significant additions to the housing elements, which also led to a more time-consuming review and analysis by HCD and more effort in revisions by local jurisdictions.

HCD’s Role as Defined in Law

Housing element law requires HCD to review local jurisdictions’ housing elements and give them a written determination on whether the housing element substantially complies with state law, but it does not expressly authorize HCD to change or enlarge statutes. HCD provides its written determinations on the housing elements to the local jurisdictions through findings letters. The determinations in findings letters state whether the local jurisdiction’s housing elements meet compliance; and, if the housing elements do not meet compliance, the letter includes information on what requirements the jurisdiction must address. The findings letters also include additional details, such as suggestions and recommendations for local jurisdictions that are advisory in nature and which HCD intends to guide jurisdictions toward compliance, rather than mandate specific actions. Some local jurisdictions indicated that the letters alone did not provide sufficient information for them to understand how to address HCD’s findings. For example, according to Anaheim staff, the feedback did not show them how to reach compliance, and they could not progress with the city’s housing element with the feedback in the letters alone. However, local jurisdictions have significant discretion to determine how best to satisfy statutory requirements. Attempts by HCD to impose requirements beyond its statutory authority could prompt legal challenges. Therefore, although HCD plays a critical role in approving the housing elements, the responsibility for crafting compliant elements ultimately rests with the local jurisdictions.

Increased Housing Allocations

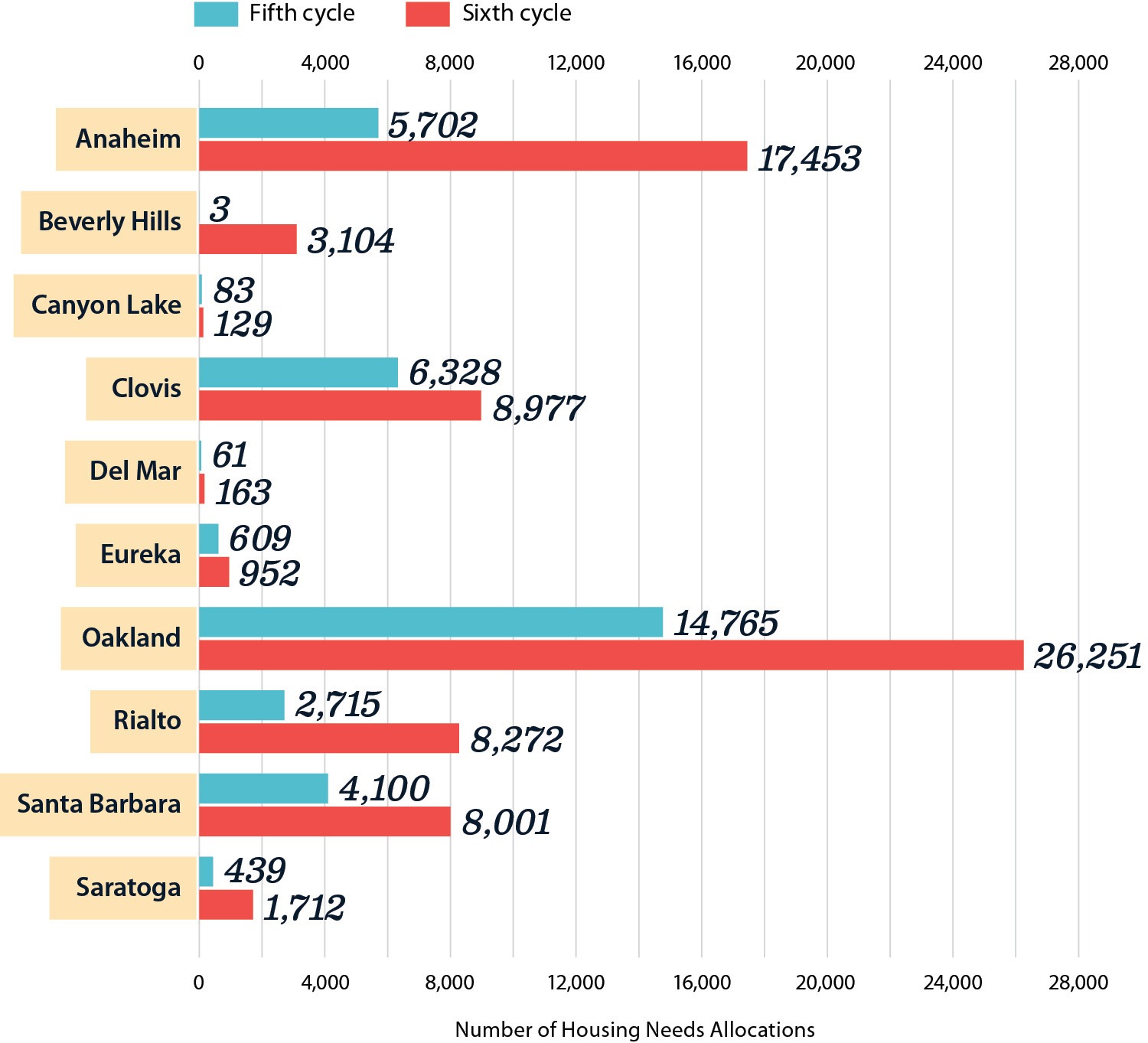

As the Introduction explains, local jurisdictions experienced significant increases in their Regional Housing Needs Allocation (housing needs allocation) in the sixth cycle. All 10 of the local jurisdictions we selected stated that they had experienced an increase in required housing needs allocations in the sixth cycle, with some having been doubled or even tripled since the fifth cycle. The local jurisdictions stated that these increases made it more difficult for them to plan for housing and, ultimately, adopt a compliant housing element. For instance, Anaheim’s housing needs allocation jumped from 5,702 housing units in the fifth cycle to 17,453 housing units in the sixth cycle. Figure 8 illustrates the increases in the housing needs allocation for each of the 10 selected jurisdictions from the fifth cycle to the sixth cycle.

Figure 8

Local Jurisdictions Had to Plan for More New Housing in the Sixth Cycle

Source: HCD’s housing needs allocations website.

Figure 8 is a modified horizontal bar chart depicting how local jurisdictions had to account for more new housing in the sixth cycle. To the left of the Y-Axis, the chart lists each of our ten selected jurisdictions in descending alphabetical order, beginning with Anaheim at the top and ending with Saratoga at the bottom. To the right of each listed jurisdiction, there are two stacked bars: a blue bar on top representing the fifth cycle housing allocation, and a red bar on the bottom representing the sixth cycle allocation.

First, the chart indicates that Anaheim had a fifth cycle allocation of 5,702 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 17,453.

Second, the chart indicates that Beverly Hills had a fifth cycle allocation of 3 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 3,104.

Third, the chart indicates that Canyon Lake had a fifth cycle allocation of 83 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 129.

Fourth, the chart indicates that Clovis had a fifth cycle allocation of 6,328 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 8,977.

Fifth, the chart indicates that Del Mar had a fifth cycle allocation of 61 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 163.

Sixth, the chart indicates that Eureka had a fifth cycle allocation of 609 units, and a sixth cycle allocation of 952.

Seventh, the chart indicates that Oakland had a fifth cycle allocation of 14,765 and a sixth cycle allocation of 26,251.

Eighth, the chart indicates that Rialto had a fifth cycle allocation of 2,715 and a sixth cycle allocation of 8,272.

Ninth, the chart indicates that Santa Barbara had a fifth cycle allocation of 4,100 and a sixth cycle allocation of 8,001. Finally, the chart indicates that Saratoga had a fifth cycle allocation of 439, and a sixth cycle allocation of 1,712.

Challenges With Consultants

Some local jurisdictions also noted a reliance on an external consultant for revising the housing element, which added delays for some of the jurisdictions we selected. Specifically, Canyon Lake stated that it had to hire a new consultant midway through the sixth cycle and that it had to distribute multiple rounds of requests to find one. Further, its new consultant undertook an extensive evaluation to determine the necessary changes to the city’s housing element. This evaluation contributed to a long gap of more than 1.5 years between Canyon Lake receiving HCD’s review and the city resubmitting the next draft. Beverly Hills also experienced challenges with its consultant, which contributed to delays in the approval process. Beverly Hills explained that its initial consultant would try to push back against HCD on its findings instead of incorporating them, which resulted in the city not resolving many of HCD’s findings. The city stated it was able to work through HCD’s findings once it began working with a different consultant who had more recent experience working with HCD. Similarly, Santa Barbara stated that after six months of searching, it was unable to hire a consultant to work on the city’s housing element, which resulted in staff putting other projects on hold so they could work on the housing element. HCD explained that because two-thirds of all local jurisdictions have housing element deadlines within the same two-year period, local jurisdictions may struggle to find available consultants.

Community Opposition to New Housing

Local jurisdictions’ social and political environments, and their proclivity—or lack thereof—toward developing housing can contribute to the lengthy approval process. Saratoga explained that the city was originally planned and designed to be a low‑density, single-family area, and that its community is anti-development. Saratoga further indicated that residents had numerous issues with the affordable housing requirements within housing elements, and that even building a two-story building could take more than a year to develop. Canyon Lake similarly explained that nearly all of its housing is within gated areas and that all residential properties are subject to rules and regulations of the same property owner’s association. Canyon Lake further stated that the area was originally intended as a senior and retirement area, with predominately small single-family lots.

Some news articles have reported on other local jurisdictions that disagree with or are resistant to developing housing. For instance, one news article reported multiple instances in which local jurisdictions attempted to make changes to their housing elements to reduce the amount of planned housing within them. Another news article indicated that even though the city of Piedmont—a local jurisdiction we did not review—has an approved housing element, residents are fighting the plan to add a minimum of 132 residential units, with 60 units of affordable housing, claiming that the development may conflict with evacuation routes. When local jurisdictions have residents that oppose residential development, those jurisdictions may have a more difficult time developing, adopting, and implementing an approved housing element.

Local Jurisdictions Face Consequences When They Delay Adopting Compliant Housing Elements

Although state law requires each local jurisdiction to adopt a revised housing element by a specific deadline, many local jurisdictions failed to do so during the most recent cycle. In fact, as of November 2024, 128 of the 539 local jurisdictions—or 24 percent—had not adopted a revised, HCD-approved housing element for the sixth cycle.6 Further, only six of the 411 jurisdictions that had adopted revised, HCD‑approved housing elements did so by their statutory deadline.7 As the text box describes, adopting a revised housing element late can lead to significant consequences for local jurisdictions.

Consequences of Late Housing Elements

Builder’s remedy: A legal tool in state law that allows developers of low- to moderate-income housing projects to bypass certain local zoning rules if a local jurisdiction has not adopted an HCD-approved housing element.

Legal challenges: Local jurisdictions can face lawsuits from private parties or the state attorney general, which can result in court orders and restrictions on permitting.

Condensed rezoning: Local jurisdictions that adopt housing elements late must complete mandatory rezoning more quickly than those that meet deadlines, which can create administrative pressure.

Potential loss of funding: Local jurisdictions risk losing eligibility or scoring advantages for state housing programs and grants.

Source: State law, HCD’s website, and interviews with local jurisdictions.

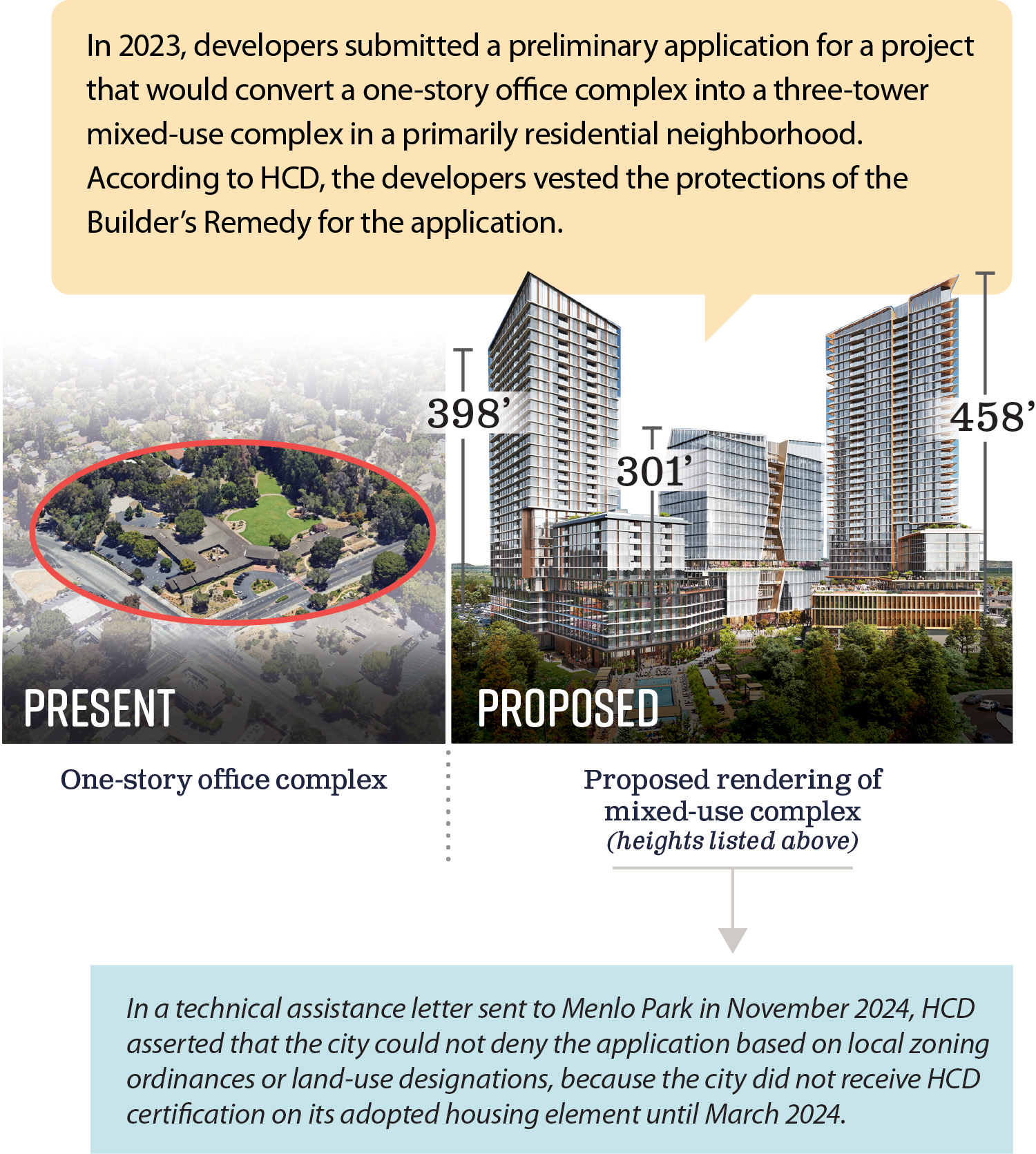

One possible consequence of a late housing element is the builder’s remedy. The builder’s remedy refers to a provision of state law that prevents a local jurisdiction from denying proposed housing projects based on local zoning ordinances if the local jurisdiction has not adopted a revised housing element that is substantially compliant with housing element law, if the proposed development is for very low, low, or moderate-income households8 and if it meets certain other requirements. In practice, the builder’s remedy allows developers to obtain approval for projects that a local jurisdiction might otherwise deny, even if the projects significantly exceed local height density, and other land-use restrictions. Figure 9 shows an example of a potential builder’s remedy consequence in Menlo Park. Three of the local jurisdictions we interviewed have faced applications by developers for a builder’s remedy.

Figure 9

Builder’s Remedy Presents a Significant Consequence for Noncompliant Local Jurisdictions

Source: HCD documentation, state law, City of Menlo Park website, and news articles.

Figure 9 is a graphic depicting how the builder’s remedy presents a significant consequence for noncompliant local jurisdictions, using the example of Menlo Park. The graphic indicates via a text box that, in 2023, developers submitted a preliminary application for a project that would convert a one-story office complex into a three-tower mixed-use complex in a primarily residential neighborhood. The graphic states in the text box that, according to HCD, the developers vested the protections of the builder’s remedy for the application.

Below the text box, the graphic depicts two images. On the left, the graphic shows the present-day one-story office complex of the proposed development. On the right, the graphic shows the proposed rendering of the mixed-use complex with three towers of 398, 301, and 458 feet in height.

Finally, at the bottom, the graphic indicates via a text box that, in a technical assistance letter sent to Menlo Park in November 2024, HCD asserted that the city could not deny the application based on local zoning ordinances or land use designations, because the city did not receive HCD certification on its adopted housing element until March 2024.

In addition, state law establishes that any interested party may bring legal action against a local jurisdiction that is not in compliance with certain provisions of the housing element law. A news article9 from September 2022 reported that the nonprofit housing interest group Californians for Homeownership, Inc., had independently sued nine local jurisdictions in Southern California for noncompliance with housing element law. The article reported that the nonprofit specifically singled out these jurisdictions because it determined that they were unlikely to adopt housing elements within the next six to 12 months without litigation forcing them to do so. One of the lawsuits resulted in a December 2023 court order that suspended Beverly Hills’s authority to issue all building permits that did not effectively create new housing units, with limited exceptions, until the city adopted a compliant housing element.

Since 2018, state law has also authorized HCD to recommend that the Office of the Attorney General pursue legal action against local jurisdictions that do not adopt a compliant revised housing element. However, HCD staff stated that the department’s preference is to provide individualized assistance to help jurisdictions come into compliance before it pursues punitive measures. We identified six instances from 2018 through 2025 in which legal action enabled HCD and a local jurisdiction to stipulate to a resolution, and we found one instance in which the Office of the Attorney General pursued litigation because HCD and the local jurisdiction were unable to reach such an agreement.10 In general, these court-approved agreements outlined paths for the jurisdictions to come into compliance with housing element law and included deadlines for submission of draft housing elements by the local jurisdictions, dates by which HCD had to provide its findings letters to the local jurisdictions, and requirements for HCD to make itself available for video conferences for a least an hour in the month following each findings letter.

Further, local jurisdictions that do not adopt compliant housing elements by the statutory deadlines have a shortened timeline for completing their rezoning—the process of changing how a piece of land can legally be used. Normally, if a local jurisdiction adopts an HCD-approved housing element within 120 days of the required statutory deadline, the jurisdiction has three years to complete rezoning.11 However, if a local jurisdiction adopts its housing element more than 120 days after its statutory deadline, the jurisdiction has one year instead of three years to complete rezoning. If a local jurisdiction adopts its housing element more than one year after the required statutory deadline, it may not be considered in compliance with housing element law until it has completed all rezoning.

Finally, local jurisdictions risk being less competitive or losing eligibility for housing-related funding opportunities when they fail to adopt a compliant housing element revision by the required deadline. Local jurisdictions with compliant housing element revisions coupled with a prohousing designation under the State’s Prohousing Designation Program gain advantages in scoring for some state housing programs. HCD lists some of these programs on its website, and state law also provides examples of such programs that offer incentives for housing element compliance. For example, one program that requires a compliant housing element is the Permanent Local Housing Allocation (PLHA). PLHA provided more than $326 million in funding in 2023, and Oakland, one of our 10 selected jurisdictions, had received nearly $12.1 million from the PLHA program as of May 16, 2023.

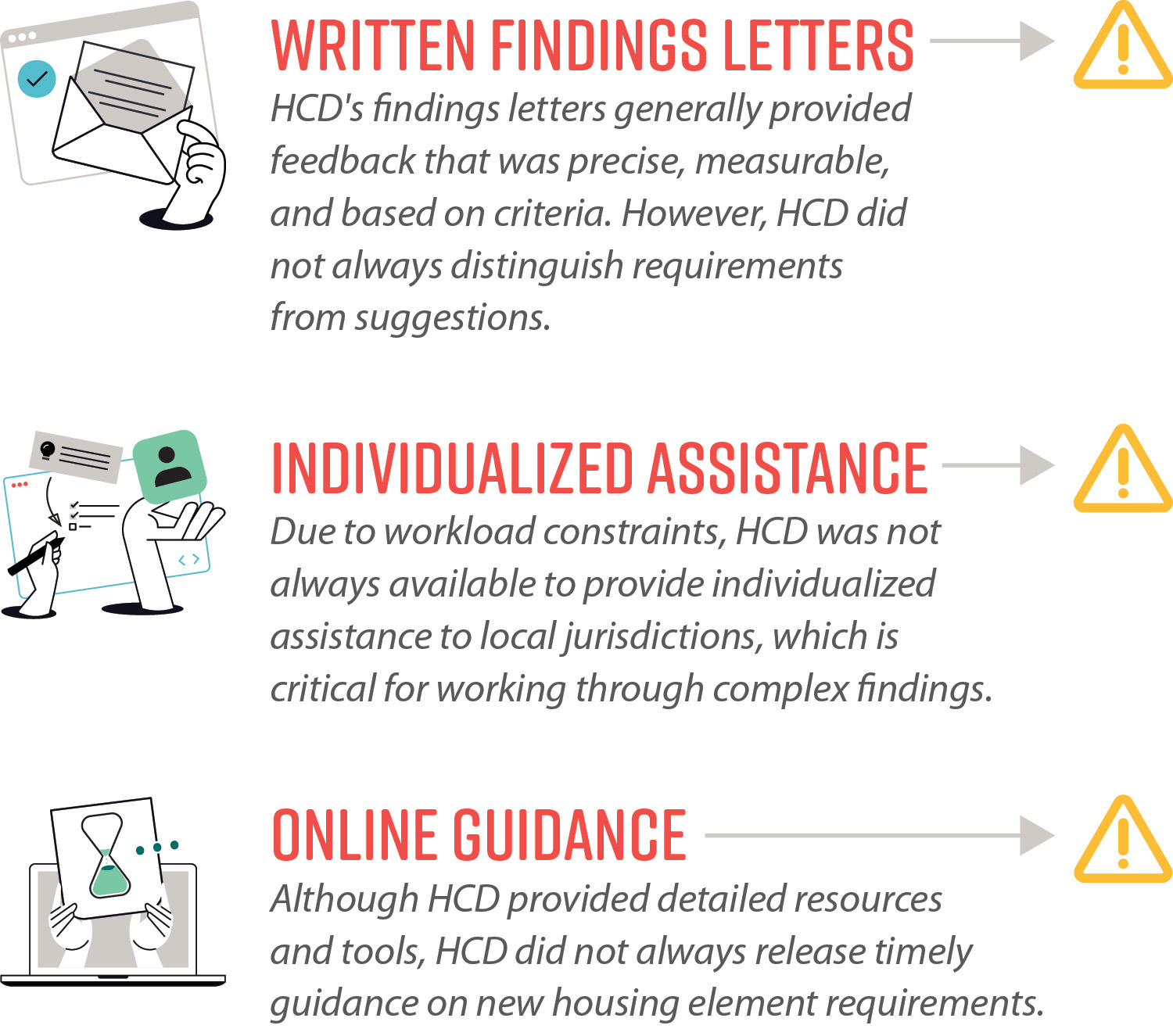

Increased Individualized Support From HCD Is Critical to Shortening the Approval Process

HCD provides three types of assistance to local jurisdictions: findings letters, individualized assistance, and online guidance and resources. However, as Figure 10 describes, HCD could improve all three types of assistance to better support local jurisdictions in achieving housing element compliance. For instance, although the individualized assistance that HCD provides helps local jurisdictions to understand how to address its findings, HCD’s workload challenges prevent it from always providing such support. Additionally, although HCD’s online guidance is detailed, HCD has not always issued some guidance in a timely manner.

Figure 10

HCD Could Improve All Three of the Types of Assistance It Provides to Local Jurisdictions

Source: Audit testing results.

Figure 10 is an organization chart describing how HCD could improve all three types of assistance it provides to local jurisdictions: written findings letters, individualized assistance, and online guidance. The graphic depicts three sections, and each section describes one of the previously-mentioned types of assistance.

In the first section, the graphic describes the findings letters. The graphic indicates that HCD’s findings letters generally provided feedback that was precise, measurable, and based on criteria, but that HCD did not always distinguish requirements from suggestions.

In the second section, the graphic describes individualized assistance. The graphic indicates that, due to workload constraints, HCD was not always available to provide individualized assistance to local jurisdictions, which is critical for working through complex findings. In the third section, the graphic describes online guidance. The graphic indicates that, although HCD provided detailed resources and tools, HCD did not always release timely guidance on new housing element requirements.

HCD Delivers Valuable Written Feedback to Local Jurisdictions, but Individualized Assistance Would Provide Additional Clarity

As the Introduction explains, HCD reviews local jurisdictions’ draft housing element updates, determines whether they comply with state law, and reports its determination to the local jurisdiction through a findings letter. Although the housing element law requires HCD to report its findings to local jurisdictions in writing, it does not require these letters to provide local jurisdictions with guidance or prescriptive instruction on how to achieve compliance. The text box lists the information that HCD includes in its findings letters.

HCD Includes the Following in Its Findings Letters:

- Feedback for each topic area HCD determined was not compliant with details of the relevant statute.

- An explanation of why the housing element does not comply.

- Suggestions and recommendations for how local jurisdictions can become compliant.

Source: HCD findings letters and court cases.

Note: State agencies, like HCD, generally may not impose mandates that are not found in statute unless the Legislature authorizes them to do so.

The Audit Committee asked us to determine whether HCD’s reviewers provided local jurisdictions with feedback and comments that were precise, measurable, and based on criteria. To make this determination, we reviewed six commonly occurring findings, which Figure 11 lists, in the letters HCD provided to each of the 10 selected local jurisdictions for a total of 60 findings. Four findings topics we reviewed addressed two key areas that local jurisdictions reported as challenging during the sixth cycle—the AFFH analysis and the sites inventory.

Figure 11

We Reviewed HCD’s Findings Letters Provided to Local Jurisdictions for Six Findings Topics

Source: Findings letters, state law, and HCD’s website.

Note: Some local jurisdictions’ letters did not include all of these findings categories and topics. In such cases, we judgmentally selected a similar finding from the same category.

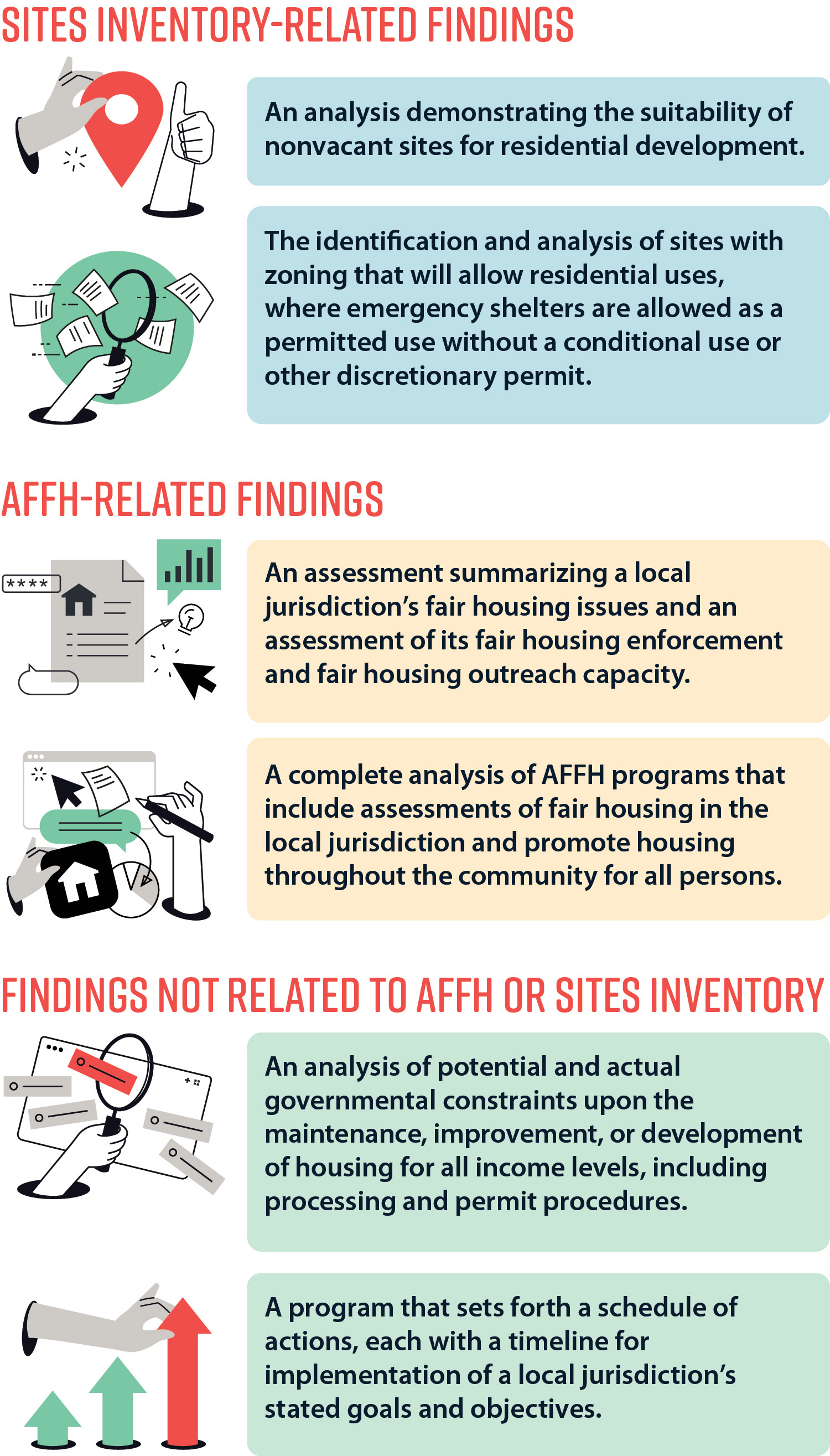

Figure 11 is an organization chart depicting three findings categories we reviewed from HCD’s findings letters sent to local jurisdictions: sites inventory-related findings; AFFH-related findings; and findings not related to AFFH or sites inventory. The chart has three sections, one for each findings category we reviewed.

The first section summarizes the two sites inventory-related findings we reviewed: first, an analysis of demonstrating the suitability of nonvacant sites for residential development; second, the identification and analysis of sites with zoning that will allow residential uses, where emergency shelters are allowed as a permitted use without a conditional use or other discretionary permit.

The second section summarizes the two Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing findings we reviewed: first, an assessment summarizing a local jurisdiction’s fair housing issues and an assessment of its fair housing enforcement and fair housing outreach capacity; second, a complete analysis of AFFH programs that include assessments of fair housing in the local jurisdiction and promote housing throughout the community for all persons. The third section summarizes the two findings we reviewed not related to AFFH or sites inventory: first, an analysis of potential and actual governmental constraints upon the maintenance, improvement, or development of housing for all income levels, including processing and permit procedures; second, a program that sets forth a schedule of actions, each with a timeline for implementation of a local jurisdiction’s stated goals and objectives.

Our testing found that HCD’s findings letters were generally precise, measurable, and based on criteria, terms that we define in the text box. Specifically, 59 of the 60 findings we tested were precise and measurable. For example, as Figure 12 illustrates, HCD gave Santa Barbara specific instruction to add discrete timelines with dates to its programs. HCD also listed examples of programs Santa Barbara needed to revise.

Attributes We Reviewed in HCD’s Findings:

- Precise: The finding is clear, unambiguous, and specific and it refers to actionable items at a more granular level rather than a higher level.

- Measurable: The finding is quantifiable, objective, or contains concrete/finite feedback for addressing the issue. The finding is also actionable and provides an identified pathway toward achieving compliance.

- Based on Criteria: The finding is supported by state law and/or HCD guidance.

Source: U.S. Office of Personnel Management, U.S. Government Accountability Office, and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Figure 12

HCD Provided Santa Barbara With Meaningful Instruction for Its Housing Program

Source: HCD findings letter for Santa Barbara.

Figure 12 is a graphic depicting how HCD provided Santa Barbara with meaningful instruction for its housing program. The graphic depicts a page from HCD’s review letter sent to Santa Barbara on November 16, 2022, providing feedback on the city’s housing programs. The graphic indicates that, at the top of the page, HCD provided the statute related to its finding. Next, the graphic indicates where HCD detailed that the programs should have discrete timelines. Finally, the graphic indicates where HCD listed examples of programs that should be revised and provided guidance on how they could be revised.

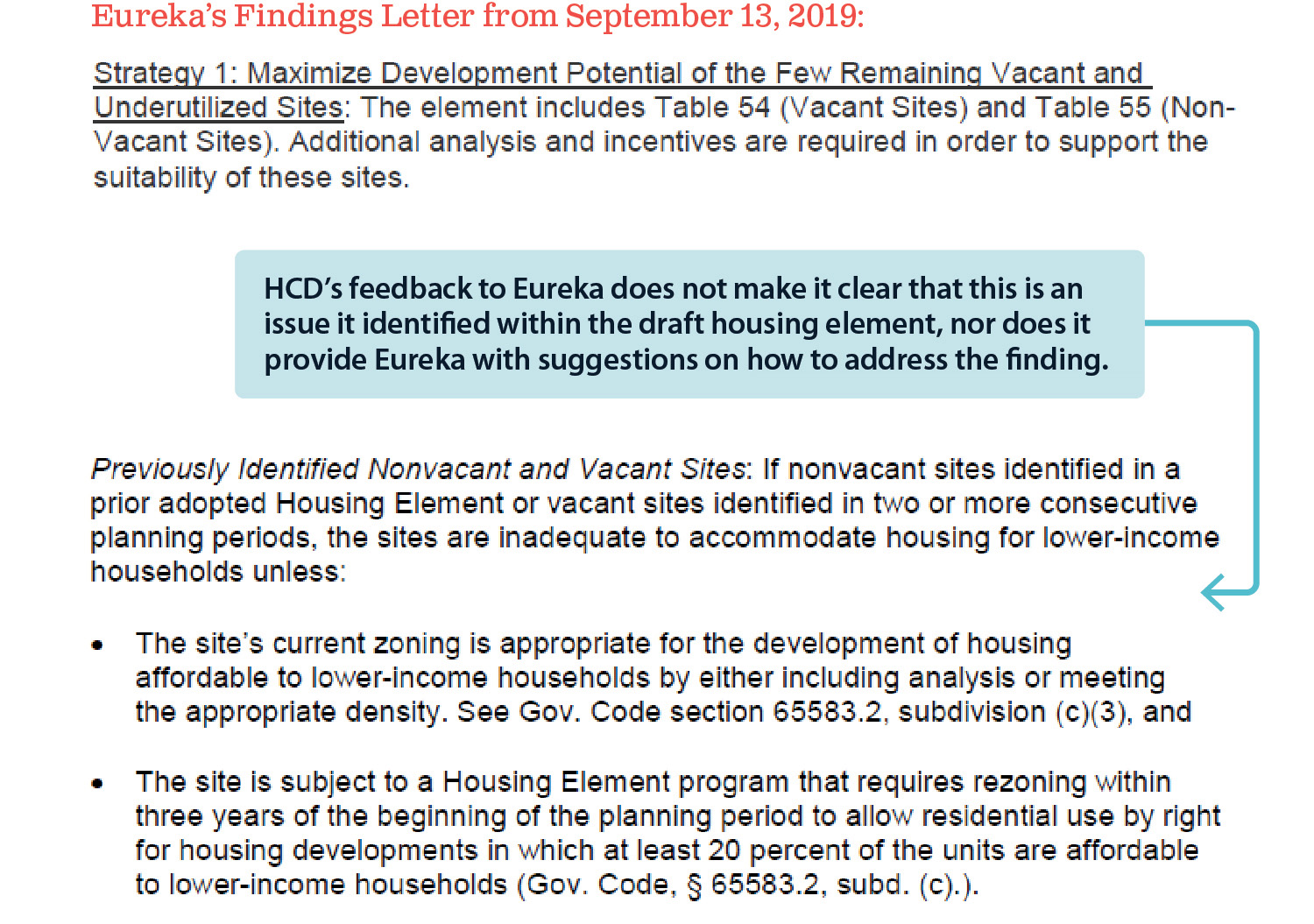

We identified only one finding that was not precise and measurable. In HCD’s findings letter to Eureka, HCD discussed the finding about previously identified nonvacant and vacant sites, as Figure 13 shows. The finding does not clearly identify the issue within Eureka’s draft housing element, and it does not present possible solutions to remedy the finding. When we met with HCD to discuss our determination that this finding was not precise and measurable, an HCD manager disagreed and expressed the belief that the finding was sufficiently precise and specific for Eureka to apply to their housing element. The findings letter in question was from September 2019—the oldest letter we reviewed. Given the letter’s age and the fact that we did not identify similar issues in the other letters in our selection, we determined that this finding was not a significant concern.

Figure 13

In the Finding We Reviewed, HCD Did Not Provide Precise and Measurable Feedback to Eureka

Source: HCD’s findings letter to Eureka.

Figure 13 is a graphic depicting a finding from HCD’s findings letter to Eureka dated September 13, 2019, where HCD did not provide precise and measurable feedback. The graphic focuses on a finding related to Previously Identified Vacant and Nonvacant Sites, where HCD stated that if nonvacant sites identified in a prior adopted Housing Element or vacant sites identified in two or more consecutive planning periods, the sites are inadequate to accommodate housing for lower-income households unless they meet certain specific criteria. The graphic indicates that this feedback HCD sent to Eureka does not make it clear that the finding was an issue identified with the housing element draft, nor does it provide Eureka with suggestions on how to address the finding.

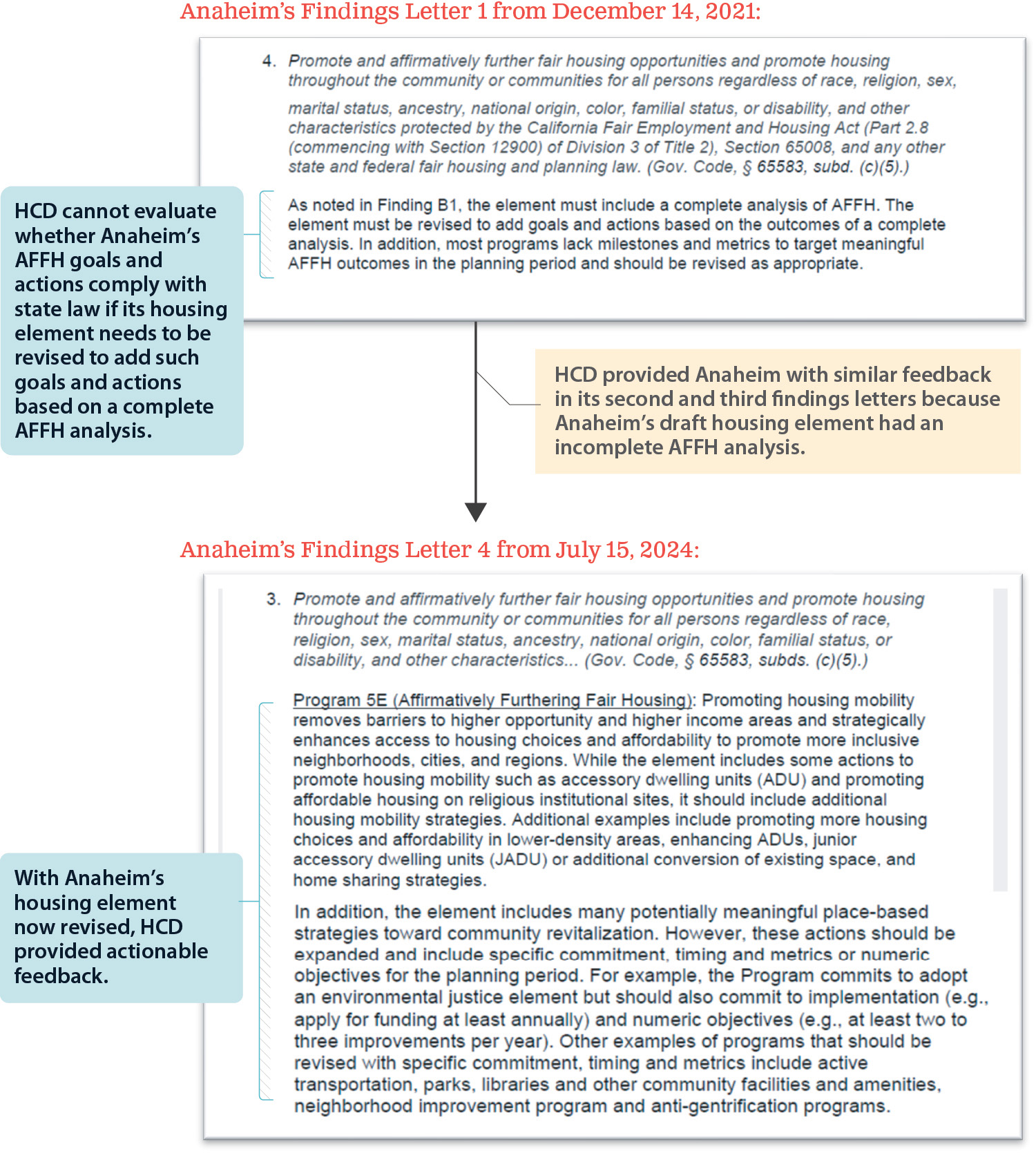

Further, when a local jurisdiction’s housing element was either substantially or entirely lacking required analyses, HCD offered general feedback to complete the missing sections. In one example that Figure 14 shows, HCD offered only general feedback to Anaheim about its AFFH programs because the AFFH section of Anaheim’s draft element was incomplete. In subsequent drafts, when Anaheim provided HCD with additional information, HCD gave more specific feedback that included precise guidance on how Anaheim should modify its programs.

Figure 14

HCD Offered General Feedback When Local Jurisdictions Provided Incomplete Draft Housing Elements

Source: HCD’s findings letters for Anaheim.

Figure 14 is a graphic depicting two examples from findings letters sent to Anaheim where HCD offered general feedback because Anaheim provided incomplete draft housing elements. The graphic took the first example from Anaheim’s first findings letter from HCD, dated December 14, 2021. In the findings letter, HCD provides a brief paragraph stating that the housing element must include a complete analysis of AFFH. The graphic indicates via a textbox that HCD cannot evaluate whether Anaheim’s AFFH goals and actions comply with state law if its housing element needs to be revised to add such goals and actions based on a complete AFFH analysis. The graphic also indicates via a separate textbox that HCD provided Anaheim with similar feedback in its second and third findings letters because Anaheim’s draft housing element had an incomplete AFFH analysis. The graphic then provides the second example from Anaheim’s fourth findings letter from HCD dated July 15, 2024. In the letter, HCD provides multiple detailed paragraphs with specific feedback on Anaheim’s AFFH programs. The graphic indicates via a textbox that, with Anaheim’s housing element now revised, HCD provided actionable feedback.

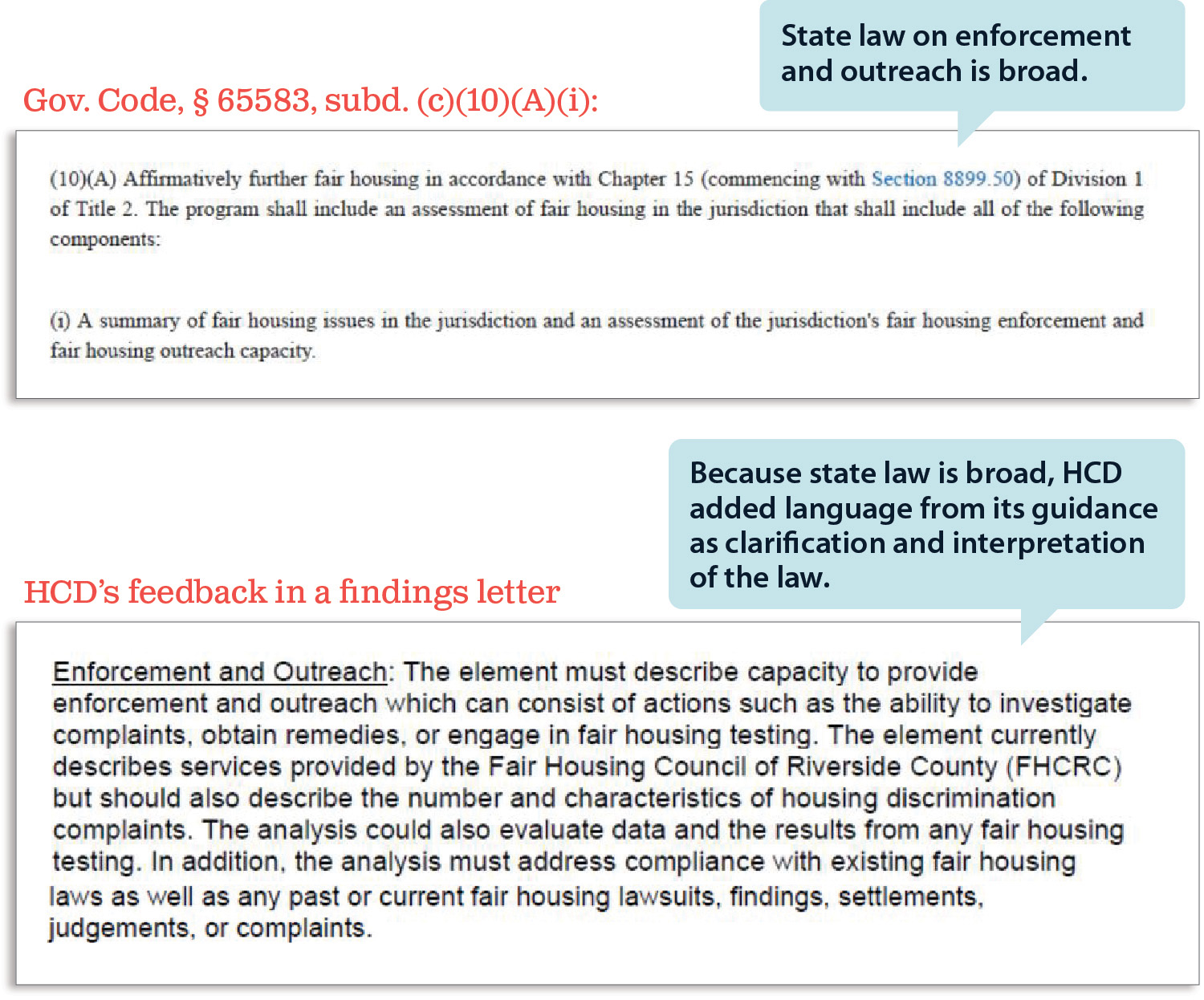

HCD provided feedback based on criteria—feedback that is supported by law or online guidance—to local jurisdictions in its findings letters. We reviewed the same 60 findings to determine whether the feedback was based on criteria and whether the language in these findings aligned with state law. Specifically, 50 of the 60 findings we reviewed included language that directly aligned with state law. The remaining 10 findings had some language that was not clearly based in law but was based on HCD’s online guidance. We therefore determined that all 60 findings were based on criteria. For these 10 findings, the requirements in state law are broad, and HCD’s online guidance provides additional clarity and direction for jurisdictions. Figure 15 is an example of one finding in which HCD added language from its online guidance to provide additional clarity on the law. This finding is based on the state law requirement that a local jurisdiction shall include in its AFFH analysis an assessment of a local jurisdiction’s fair housing enforcement and outreach capacity; however, as Figure 15 demonstrates, state law does not describe what this assessment should look like or contain. To address this gap, HCD’s findings letters include information from its online guidance that details what these assessments should include.

Figure 15

HCD’s Feedback in Some Cases Contained Language That Was Not Clearly Supported in Law but Was Clearly Supported in HCD Guidance

Source: State law and HCD’s written findings letter to Canyon Lake.