2023-126 California Community Colleges

Oversight of the 50 Percent Law Is Ineffective, and the Law Could Be Amended to Better Support Students

Published: April 8, 2025Report Number: 2023-126

April 8, 2025

2023‑126

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the California Community Colleges (CCC), which included a review of 10 of the 73 CCC districts (districts). Our evaluation focused on districts’ compliance with the 50 Percent Law and district investment in administrators compared to faculty and support staff. All districts are subject to a state law that generally requires them to spend at least 50 percent of their current expense of education on the salaries of classroom instructors—meaning that a compliance rate of 50 percent or greater meets the law’s requirements. The following report details the audit’s findings and conclusions.

My office determined that the 50 Percent Law limits districts’ ability to fund services outside of the classroom that may better support student success. The modern higher education landscape is vastly different than when the 50 Percent Law was passed in 1961, and the law in its current form does not account for these changes, such as the larger role of support from counselors and librarians, and technological changes. Additionally, although most of the 73 districts report that they have complied with the 50 Percent Law, the Chancellor’s Office’s limited oversight allowed multiple districts to inaccurately report their compliance rates. This was, in part, due to the Chancellor’s Office not providing regular trainings to districts on reporting requirements and not conducting its own review of districts’ reporting. Lastly, available data indicate that districts’ investment in administrators has increased at a greater rate than that for faculty. The most common factor cited by districts for this increase was the need to hire managers to administer expanding grant programs. To address our findings, the Legislature could amend the 50 Percent Law to better support student success and the Chancellor’s Office should provide districts with regular trainings for reporting on the 50 Percent Law.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ACBO | Association for Chief Business Officials |

| CCC | California Community Colleges |

| CDE | California Department of Education |

| CPA | Certified Public Accountant |

| FON | Faculty Obligation Number |

| FTE | Full-time equivalent |

| FTES | Full-time equivalent students |

| ISA | Instructional Service Agreements |

| MIS | Management Information System |

| SCFF | Student Centered Funding Formula |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The California Community Colleges (CCC) are overseen by the Office of the Chancellor of the CCC (Chancellor’s Office) and serve nearly two million students at 73 districts across the State. All CCC districts (districts) in California are subject to a state law that generally requires them to spend at least 50 percent of their current expense of education (Current Educational Expense) on the salaries of classroom instructors (Instructor Salaries)—meaning that a compliance rate of 50 percent or greater meets the law’s requirements. This law is commonly referred to as the 50 Percent Law. Enacted in 1961, the law was based on a Senate fact‑finding committee’s proposal to reduce class size and improve student success.

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) asked us to review a selection of 10 districts’ compliance with the 50 Percent Law, the Chancellor’s Office’s oversight of districts’ compliance, and overall district investment in administrators compared to faculty and support staff. Our review concluded that because of the evolution of classroom instruction since the law’s enactment, districts must weigh complying with the law against increasing their spending on noninstructional services that may also support students, such as spending on librarians, counselors, and new technology. Further, we found that most of the 73 districts reported having complied with the 50 Percent Law, but that the Chancellor’s Office’s oversight of compliance is insufficient, allowing for districts’ incorrect reporting to remain undetected.

The 50 Percent Law Limits Districts’ Ability to Fund Services Outside of the Classroom That Support Student Success

Modern higher education is vastly different than it was in the 1960s, and student instruction and learning now often requires advanced technologies, virtual instruction, and support for students outside of the traditional learning space. Because only the salaries and certain benefits of classroom instructors and instructional aides are included as Instructor Salaries in the 50 Percent Law’s compliance calculation, the 50 Percent Law forces districts to weigh spending enough on the salaries of classroom instructors to comply with the law against providing other services that do not contribute to compliance but still support student success. If the Legislature were to amend the 50 Percent Law to include the salaries of support services personnel, such as those of librarians and counselors, into the Instructor Salaries portion of the formula, it could increase districts’ compliance rates while also helping students succeed.

We reviewed 10 districts’ spending on basic needs services, such as programs that help students with food and housing.1 Although the districts we reviewed tracked information on basic needs services spending inconsistently, most districts reported that basic needs services spending does not significantly affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. Because the Chancellor’s Office does not fully prescribe how districts should account for all basic needs services, districts did not consistently track expenses for them. Most of the districts that were able to provide self‑reported information regarding their funding for basic needs services indicated that basic needs services are primarily funded using funds whose use is restricted to a specific purpose (restricted funds), such as federal or state grants. Restricted funds are excluded from the 50 percent formula and therefore do not affect districts’ compliance rates. However, some districts we reviewed explained that if restricted funds become less available, districts might need to cut services, find other restricted funding, or use unrestricted funding to pay for basic needs services. Using unrestricted funds to pay for basic needs services could affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

The Chancellor’s Office’s Limited Oversight Allowed Multiple Districts to Inaccurately Report Their Compliance Rates

Districts are required to report compliance with the 50 Percent Law to the Chancellor’s Office in their annual financial and budget reports (financial reports), and from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, only five of the 73 districts self‑reported noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law. The Chancellor’s Office relies on annual Certified Public Accountant (CPA) audits to gain confidence in the accuracy of these financial reports, including the 50 percent calculation, but we found errors in reporting from many of the districts we reviewed that the CPA audits did not identify. We reviewed 30 transactions that took place during five fiscal years at each of the 10 districts we selected for review, for a total of 300 transactions. The errors we identified included districts incorrectly reporting certain transactions as Instructor Salaries and incorrectly categorizing noninstructional personnel. The districts’ reporting errors we identified resulted in them overstating their compliance rates. However, not all cases resulted in a large enough change to affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

We attribute the errors, in part, to a lack of guidance and oversight from the Chancellor’s Office. The training that the Chancellor’s Office provides to districts is insufficient and its guidance is sometimes incorrect or unclear. Additionally, the Chancellor’s Office lacks an effective method to hold certain noncompliant districts accountable. Its current method is to withhold state apportionment money from noncompliant districts; however, the districts that repeatedly report noncompliance are districts that do not receive state apportionment funds and are supported by community funding. Because there is no state apportionment funding to withhold from these districts, the Chancellor’s Office lacks a mechanism to hold these districts accountable for complying with the 50 Percent Law.

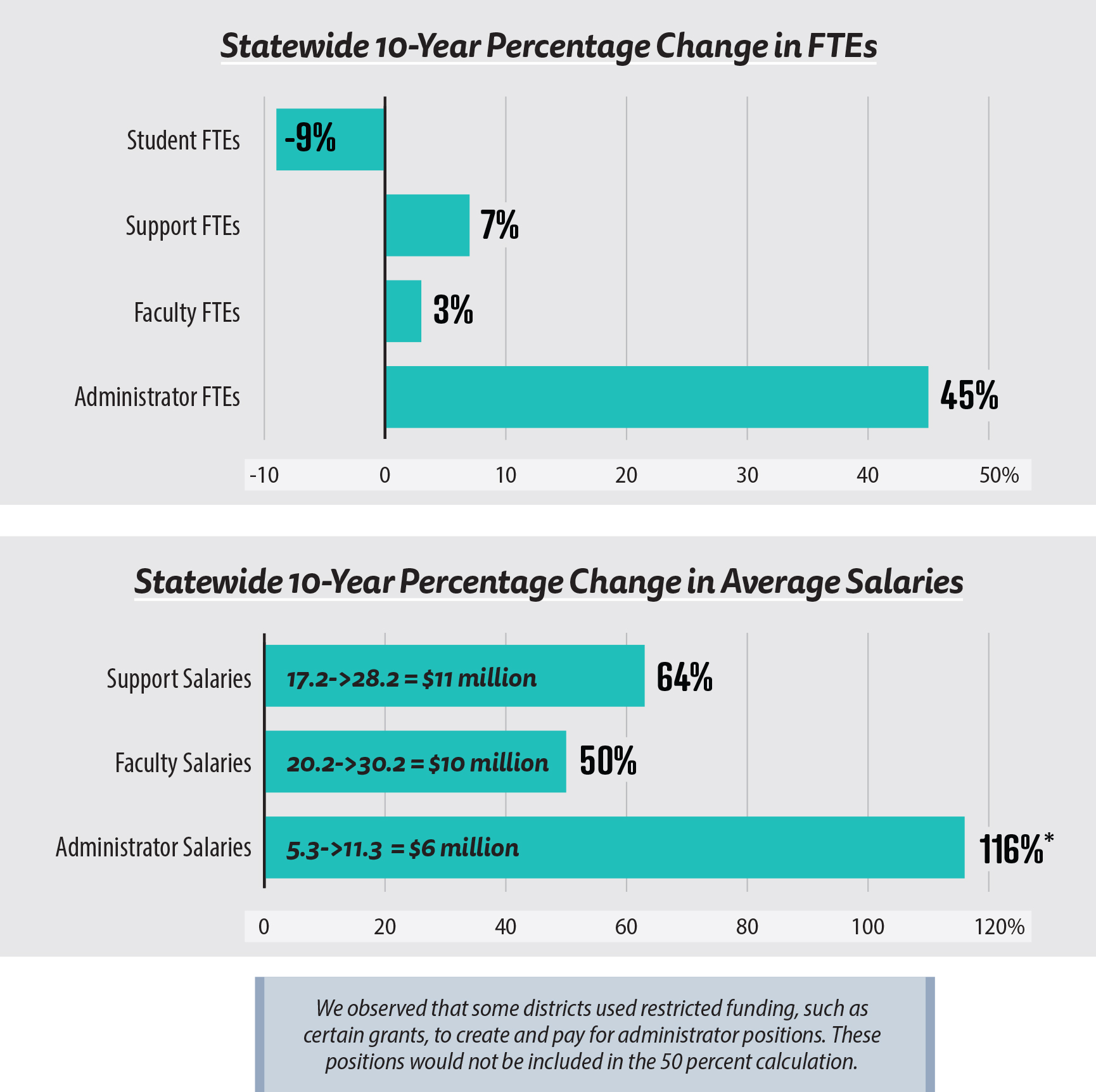

Available Data Indicate That Districts’ Investment in Administrators Has Increased at a Greater Rate Than Their Investment in Faculty

Data show that districts’ investment in administrators, including management and executives, far outpaced their investment in faculty, which includes classroom instructors. Statewide data show that from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2023–24, districts increased the number of administrators by 45 percent compared to an increase of just 3 percent for faculty and 7 percent for support staff. However, we identified anomalies and discrepancies in the Chancellor’s Office statewide staffing and salary data that made us question its reliability. Nevertheless, because it is the most readily available source of the aggregate data across 73 districts, we present the Chancellor’s Office’s data in this report.

The districts we reviewed pointed to several factors that contributed to this increased spending on administrators. The most common factor they cited was the need to hire managers to administer expanding grant programs, such as personnel to manage grants. Although districts have discretion to create new administrator positions, districts’ justifications for creating those positions were inconsistent. For example, our review of documentation districts use when creating and justifying new positions found that many districts referenced workload, but some districts did not always make a direct connection to workload needs. Regardless of staffing changes, student success outcomes appear to have increased statewide during the last five fiscal years.

To address these findings, we recommend that the Legislature consider including the salaries and benefits of librarians and counselors in Instructor Salaries, or the numerator of the 50 percent formula, and excluding technology expenses related to instruction from the 50 percent formula. To offset the impact of including additional costs in the numerator, the Legislature may also consider raising the compliance requirement to above 50 percent. We also propose that the Chancellor’s Office provide the districts with regular training and clarify its existing guidance for districts’ reporting on the 50 Percent Law.

Agency Comments

The Chancellor’s Office agreed with our recommendations and indicated that it will take actions to implement them. Because we did not make recommendations to the 10 districts we reviewed, we did not expect a response from them; however, one district—San Mateo County Community College District—provided a response in which it disagreed with some of our findings and conclusions.

Introduction

Background

The CCC—which serves nearly two million students and comprises 116 colleges within 73 districts in the State—plays a unique role in California’s public higher education structure. Unlike the California State University and University of California institutions, community colleges must admit any California residents possessing a high school diploma or equivalent. Community colleges must provide academic and vocational instruction at the lower division level that may culminate in an associate degree or transfer to a four‑year institution.

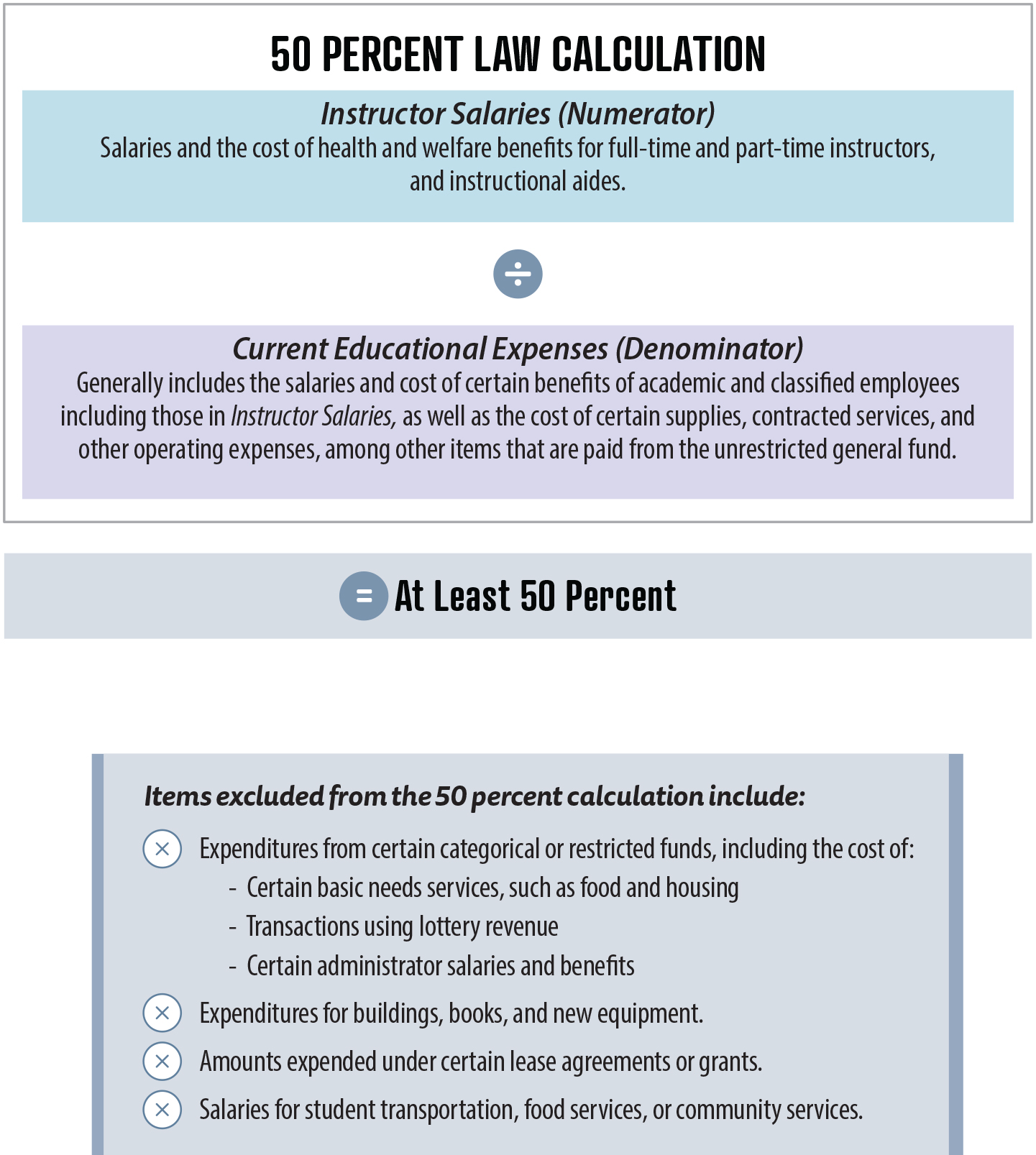

All districts in California are subject to the 50 Percent Law, which requires them to spend at least 50 percent of their current expense of education (Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator) on the salaries of classroom instructors (Instructor Salaries, or the numerator). State law describes the criteria for what districts must include in Instructor Salaries and Current Educational Expenses, as Figure 1 shows. Districts must prorate in Instructor Salaries the salaries of instructors who perform some noninstructional activities as part of their work so that only the portion of their salaries spent on instructional duties are included in the numerator of the 50 percent formula. Instructor Salaries does not include salaries of noninstructional staff, such as executives, administrators, counselors, librarians, and health professionals. The 50 Percent Law excludes portions of districts’ budgets from Current Educational Expenses, including certain state or federal grants, restricted funds, and certain types of categorical funds. Restricted and categorical funds are generally those funds whose uses are restricted to specific purposes, and would include lottery revenue.

Figure 1

The 50 Percent Law Requires Districts to Spend a Minimum Percentage of Funds on Instructor Salaries and Benefits

Source: Chancellor’s Office documents, districts’ documents, and state law.

This is an infographic that depicts a visual representation of the 50 Percent Law calculation, which requires that Instructor Salaries, or the numerator, be divided by Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator, to equal at least 50 percent. Instructor Salaries are the salaries and the cost of certain health and welfare benefits for full-time and part-time instructors, and instructional aides. Current Educational Expenses generally includes the salaries and cost of certain benefits of academic and classified employees including those in Instructor Salaries as well as the cost of certain supplies, contracted services, and other operating expenses, among other items, that are paid from the unrestricted general fund. Below the equation is a list of items that are excluded from the 50 percent calculation, which include expenditures from certain categorical or restricted funds, including the cost of certain basic needs services such as food and housing, transactions using lottery revenue, and certain administrator salaries and benefits. The list also includes expenditures for buildings, books, and new equipment; amount expended under certain lease agreements or grants; and salaries for student transportation, food services, or community services.

The bill enacting the 50 Percent Law was based on the findings and conclusions of a Senate fact‑finding committee report noting that large class sizes result in teachers giving less individual attention to students, adversely affecting students’ ability to compete with students from states with smaller class sizes. In the report, the committee proposed changes to the law to require a specific level of spending on instructor salaries in an effort to reduce classroom sizes and improve student success. In a letter urging the Governor to approve the bill enacting the 50 Percent Law, one of the bill’s authors also stated that the law in effect at the time made it possible to use state funds to hire instructors to perform administrative work rather than classroom teaching, allowing costs for administrative staffing in education to increase, and that the bill would implement sound guidelines for spending state funds for teachers’ salaries.

An 18‑member board of governors (CCC Board of Governors) governs the CCC. The CCC Board of Governors provides leadership and direction to the districts by carrying out certain responsibilities required by state law. The CCC Board of Governors appoints the Chancellor, who acts as the system‑wide chief executive officer. The CCC Board of Governors has granted the Chancellor’s Office specific oversight of aspects of districts’ fiscal management, staff monitoring, and budget‑reporting practices.

In its role as the oversight entity responsible for ensuring that districts report compliance with the 50 Percent Law, the Chancellor’s Office publishes district reporting of compliance with the law, provides guidance to districts on the law, and is responsible for holding noncompliant districts accountable. The Chancellor’s Office also distributes the Budget and Accounting Manual (accounting manual), the majority of which has the authority of regulation and which each district must follow. The accounting manual provides accounting procedures for consistent and comparable reporting of financial data by all districts. The Chancellor’s Office also operates and manages the Management Information System (MIS), as a requirement of state law. Districts are required to submit data to MIS, such as staffing numbers, annual compensation, and student success metrics.

Evolution of the CCC Since the Passage of the 50 Percent Law

Figure 2 illustrates just a few of many aspects that have changed since the State passed the 50 Percent Law in 1961. The CCC Board of Governors was itself not established until six years later in 1967. Public school employee collective bargaining rights, whereby teachers could collectively negotiate their salaries, were not established until the Educational Employment Relations Act was passed in 1975. Further, voters approved Proposition 13 in 1978, which had the effect of reducing funding for community colleges, and approved Proposition 98 in 1988, which established a minimum level of state funding for schools and community college districts.

Figure 2

Both Technology and Laws Related to the CCC Have Changed Since the Enactment of the 50 Percent Law

Source: Chancellor’s Office reports, state law, and public websites.

The 50 Percent Law was enacted in 1961. The formation of the CCC Board of Governors occurred in 1967. The Educational Employment Relations Act passed in 1975, which established public school employee collective bargaining rights. Microsoft Windows was first released in 1985, and its products list Microsoft Word were later used by many students. The Legislature passed Assembly Bill 1725 in 1988, which recognized a goal that full-time instructors teach at least 75 percent of all hours of credit instruction. In 1993, the World Wide Web was released to the public. Google was founded in 1998, a predominate search platform used by students. In 2011, Zoom was founded and later used for online distance learning. The implementation of the Student Centered Funding Formula occurred in 2018, which allocates a portion of district funding based on student success metrics. In 2020, the pandemic leads to a shift to distance (online) education.

Since the passage of the 50 Percent Law more than 60 years ago, technological progress has also transformed the CCC. Districts today spend funds on software, computers, and other IT equipment and services that did not exist in 1961. Further, many students choose to enroll in online distance education courses, a trend accelerated by the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020. Additionally, technology such as online instruction and modernizing classrooms has changed since the law was passed and are important for student success.

In recent years, districts have also taken on more responsibility for providing support to students outside of the classroom. During the pandemic, community colleges reported using Higher Education Relief Fund Grants to improve student support services and address students’ basic needs. Support services, such as counseling and library services, help contribute to student success. According to some districts we reviewed, support services have increased over the years with the changing needs of students and are important for improving student success in the classroom. Basic needs services, some of which we list in the text box, ensure that students have the necessary resources, including food and housing. When students’ basic needs are fulfilled, they are more prepared to actively participate in the learning process, accomplish their academic objectives, and focus on their overall welfare. Some districts indicated that students’ needs and the expectations on districts to meet those student needs have changed over time. Students’ basic needs have increased over the years, such as housing and food insecurity, and mental health. Additionally, state law requires college campuses to hire basic needs coordinators. As of January 2024, every community college reported providing basic needs services to students.

Basic Needs Services:

- Housing

- Food

- Clothing

- Feminine Hygiene

- Diapers

- Childcare

- Mental Health

Source: State law.

Funding for Community College Districts

The ways in which districts receive funding vary. Most districts receive an apportionment from the State (state apportionment) in accordance with the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). Generally, the SCFF comprises three allocations that are determined by, among other items, student enrollment numbers; the number of students enrolled who have received a College Promise grant or a Pell Grant; and student success metrics, including the number of students who transfer or graduate. State law directs that a district’s state apportionments be reduced by other types of revenue, such as certain local property tax revenue or enrollment fees. For some districts, the local property tax revenues and other revenues collected by the district exceed the amount of funding they would otherwise receive in state apportionments. In these cases, state law restricts those districts from receiving state apportionment. We refer to these districts as community‑supported districts. Although only eight of the 73 community college districts are currently community‑supported, as the text box shows, three of the four districts that reported noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law in fiscal year 2022–23 were community‑supported.

Eight Districts Are Community Supported and Do Not Receive State Apportionment

- Marin

- MiraCosta

- Napa

- San José

- San Mateo

- Sierra

- South Orange

- West Valley

Source: Districts’ adopted budgets or annual audits.

Legislation That Affects, and Past Attempts to Amend, the 50 Percent Law

Complicating the picture for districts, the 50 Percent Law is not the only law that governs instructor staffing for the CCC. State law generally requires districts to adjust the number of full‑time faculty from the prior year in proportion to changes in student enrollment. This is known as the Faculty Obligation Number (FON). In 1988, the State enacted Assembly Bill 1725, which among other provisions recognized a goal that full‑time instructors teach at least 75 percent of all hours of credit instruction.

During the past two decades, there have been several legislative efforts to modify the 50 Percent Law, none of which succeeded. Assembly Bill 906, introduced in 2007, would have included the salaries of counselors and librarians in Instructor Salaries, and increased the 50 percent allocation to 53 percent. Two bills introduced in 2009, Assembly Bill 581 and Assembly Bill 1157, would have included the salaries of counselors, but not librarians, in Instructor Salaries and adjusted the compliance rate to 52 percent instead of 50 percent. Introduced in 2013, Assembly Bill 806 would have explicitly defined instructional aide salaries and incorporated counselor salaries into Instructor Salaries without providing for any change in the formula’s compliance rate at 50 percent. The most recent attempt was Senate Bill 1039, introduced in 2024, which would have included salaries of counselors and librarians in Instructor Salaries and would have redefined compliance to be when the formula rate equals 60 percent. None of these bills were enacted into law, as Table 1 shows.

Selection of Districts for Review

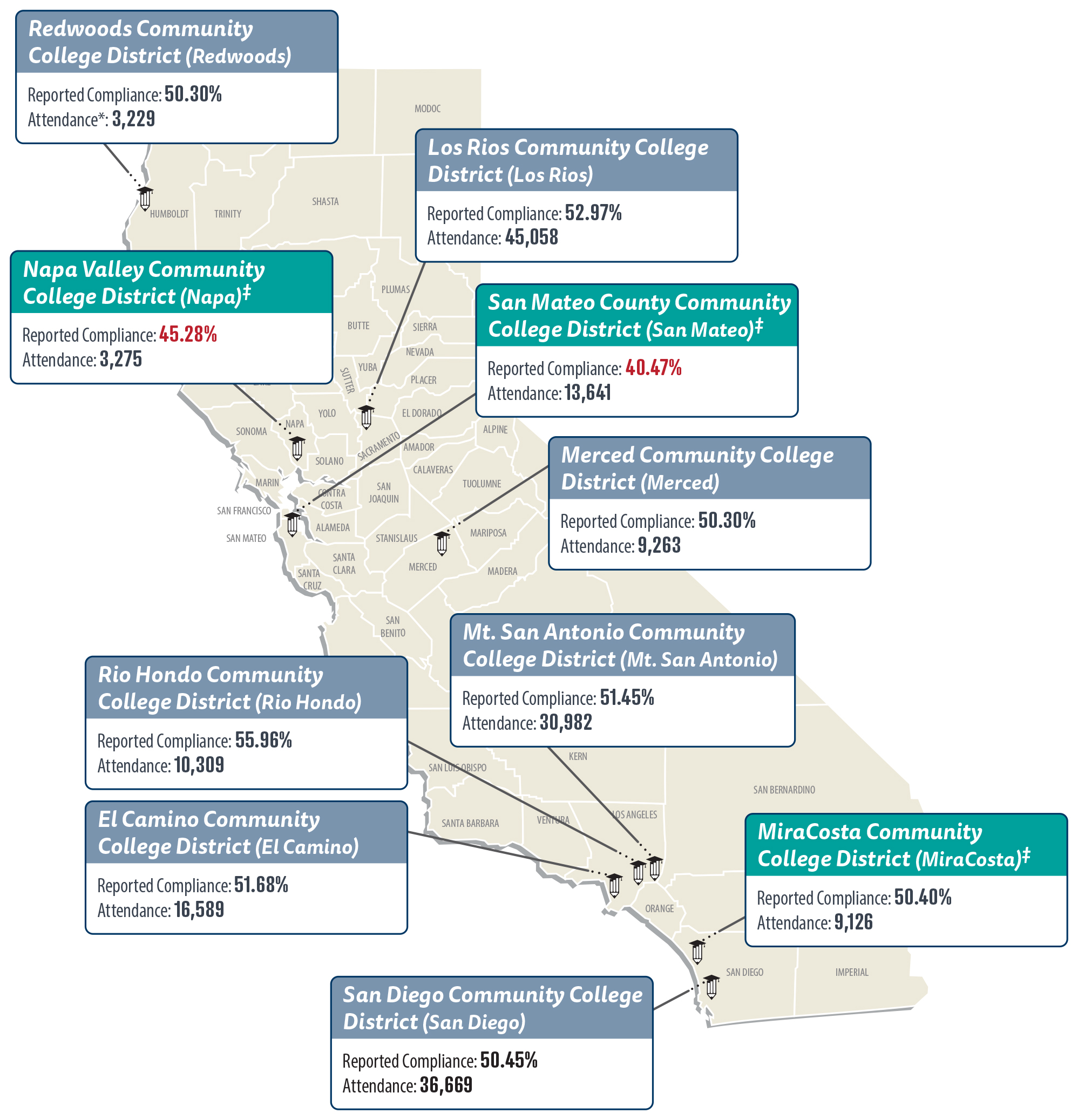

To determine whether districts appropriately reported compliance with the 50 Percent Law, we selected 10 of the 73 districts across the State. As Figure 3 shows, these 10 districts reported varying compliance rates. For example, we selected Rio Hondo, a mid‑sized district in the southern region of the State that reported a compliance rate well above 50 percent, and Redwoods, a small district in the northern area of the State that reported a rate slightly more than 50 percent. Three of the districts we selected—MiraCosta, Napa, and San Mateo—are community‑supported districts and do not receive state apportionment.

Figure 3

The 10 Districts We Reviewed Reported Varying Compliance Rates in Fiscal Year 2022–23

Source: Chancellor’s Office 50 percent compliance reports for 2022–23, Apportionment Attendance Reports for 2022–23, and districts’ annual audit reports.

Note: Refer to Table 4 for the adjusted compliance rates of districts in whose reporting we found errors that would result in noncompliance.

* To determine attendance, we used full‑time equivalent students that districts reported to the Chancellor’s Office in its Apportionment Attendance Reports in fiscal year 2022–23.

‡ Community–supported districts receive their funding from sources other than the state apportionment, including local property taxes.

This figure is a map of California showing 10 community college districts we selected for review and their reported compliance rates and student attendance numbers for fiscal year 2022-23. Specifically, from the north of California to the south, the graphic shows Redwoods with a 50.30 percent reported compliance rate and 3,229 student attendance, Napa with a 45.28 percent reported compliance rate and 3,275 student attendance, Los Rios with a 52.97 percent reported compliance rate and 45,058 student attendance, San Mateo with a 40.47 percent reported compliance rate and 13,641 student attendance, Merced with a 50.30 percent reported compliance rate and 9,263 student attendance, Mt. San Antonio with a 51.45 percent reported compliance rate and 30,982 student attendance, Rio Hondo with a 55.96 percent reported compliance rate and 10,309 student attendance, El Camino with a 51.68 percent reported compliance rate and 16,589 student attendance, MiraCosta with a 50.40 percent reported compliance rate and 9,126 student attendance, and San Diego with a 50.45 percent reported compliance rate and 36,669 student attendance.

Issues

The 50 Percent Law Limits Districts’ Ability to Fund Services Outside of the Classroom That Support Student Success

The Chancellor’s Office’s Limited Oversight Allowed Multiple Districts to Inaccurately Report Their Compliance Rates

Available Data Indicate That Districts’ Investment in Administrators Has Increased at a Greater Rate Than Their Investment in Faculty

The 50 Percent Law Limits Districts’ Ability to Fund Services Outside of the Classroom That Support Student Success

Key Points

- Complying with the 50 Percent Law may impede districts’ efforts to provide services that support student success. Amending the 50 Percent Law to include the salaries of support service personnel, such as counselors and librarians, in Instructor Salaries for the 50 percent calculation could further support student success.

- Most districts reported that basic needs services spending did not significantly affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. If the Chancellor’s Office were to amend the accounting manual to include an accounting code for basic needs services expenses, districts could consistently track their basic needs services spending.

The Legislature Could Amend the 50 Percent Law to Better Support Student Success

Spending 50 percent of their Current Educational Expenses on Instructor Salaries, as the 50 Percent Law requires, may limit districts’ ability to spend on other services that support student success. As we discuss in the Introduction, there have been significant changes in the delivery of education and student needs since the passage of the 50 Percent Law in 1961. Specifically, support services outside of the classroom, such as counseling and library services, and changes in technology play larger roles in student success today than they did when the State implemented the 50 Percent Law more than 60 years ago. The Senate fact‑finding committee report, upon which the 50 Percent Law was based, proposed legislation that sought to establish guidelines for spending state funds for instructor salaries, with the goal of reducing class sizes and improving student outcomes. The report stated that its proposed legislation would place a ceiling on state money spent outside of the classroom.

However, neither we nor the Chancellor’s Office identified any provision of state law requiring districts to report individual class size to the Chancellor’s Office or the CCC Board of Governors. In the absence of this requirement to report class size, it is difficult to know whether the 50 Percent Law has caused a decrease in community colleges’ class sizes. Although there is no metric to compare to actual class size, to respond to the Audit Committee’s calling for us to report staffing as totals and ratios, we present ratios of students to faculty. According to the Chancellor’s Office’s statewide data, the ratio of students to faculty has decreased from 33.65 students per faculty member in fiscal year 2012–13, to 29.23 students per faculty in fiscal year 2023–24, as Appendix A shows. However, the category of faculty in the statewide data include more than just individuals performing classroom instruction. The faculty category includes other personnel, such as counselors and librarians, so using this as a metric to determine class size can be misleading. Several additional factors could also affect ratios of students to faculty, such as other state laws and student enrollment numbers.

The 50 Percent Law does not contain any requirements for ensuring that the amount that the districts spend on Instructor Salaries will decrease class sizes. For example, the 50 Percent Law contains no provisions governing the number of instructors or the ratio of students to faculty that community colleges must maintain. As a result, districts can comply with the 50 Percent Law by simply increasing salaries for its current instructors rather than hiring additional instructors. Therefore, compliance with the 50 Percent Law may neither lead to an increase in the number of instructors at a district, nor does it necessarily affect a district’s average class size.

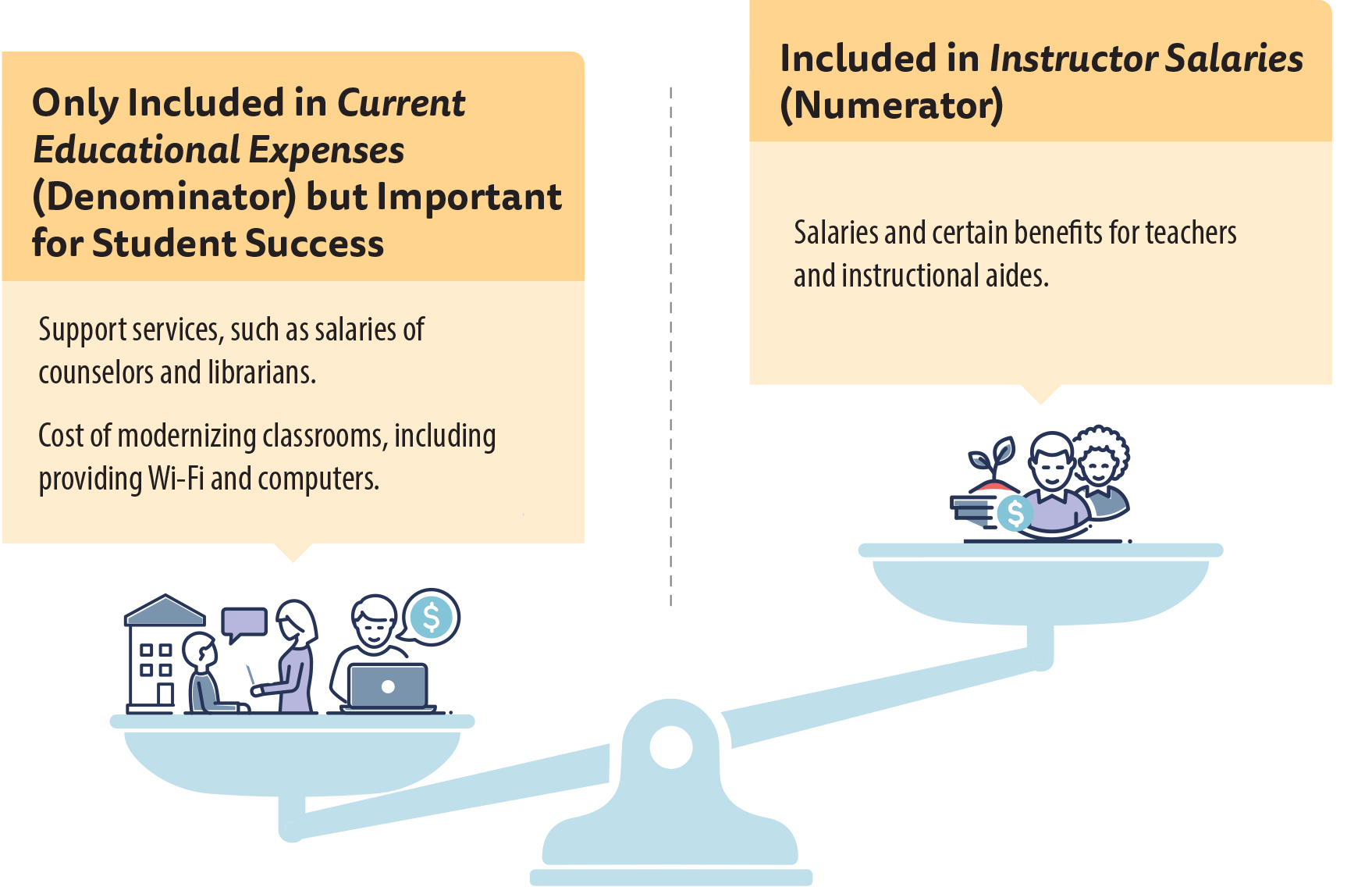

Districts must weigh complying with the 50 Percent Law against providing other services that support student success, as Figure 4 shows. Students benefit from services that take place outside of classroom instruction, such as counseling. For example, our September 2024 report, California’s Systems of Public Higher Education: Streamlining the Community College Transfer Process Could Increase Access to Bachelor’s Degrees, Report 2023-123, discusses the importance of counseling services for transfer‑intending students. Because the 50 Percent Law does not allow a district to include as Instructor Salaries the portion of a salary that is related to counseling, hiring counselors can make it difficult for districts to comply with the law. Additionally, expenses for other types of support services personnel who support student success, such as librarians, are included as Current Educational Expenses in the 50 percent calculation but not as Instructor Salaries.

Figure 4

Districts Must Weigh Complying With the 50 Percent Law Against Spending on Other Services That Support Student Success

Source: Academic Senate for CCC documents, CCC website, district personnel, and state law.

This figure is a scale showing on the left expenses that are important for student success, such as the salaries of counselors and librarians and the cost of modernizing classrooms including providing Wi-Fi and computers and are only included in Current Educational Expenses or the denominator. On the right, and higher on the scale than the expenses on the left, are the expenses included in Instructor Salaries or the numerator, which only include the salaries and certain benefits for teachers and instructional aides.

The 50 Percent Law also does not account for improvements in technology, such as online instruction and the modernization of classrooms, which may play a large role in student success. District technology and infrastructure have significantly changed since the law passed and online learning has become more common, which necessitates the increased use of technology. However, certain expenses for these technological improvements are also included in Current Educational Expenses but not as Instructor Salaries. In other words, if districts increase expenses for these support services and technology, which are included in the denominator of the 50 percent formula, it makes it more difficult for districts to comply with the 50 Percent Law. Several districts we reviewed explained that they have to weigh priorities, such as increasing support services and modernizing classrooms, with complying with the 50 Percent Law.

Including certain support service personnel in Instructor Salaries in the 50 percent calculation could have a positive impact on districts’ compliance rates. To determine the potential effect of including support services as Instructor Salaries, we identified two accounting codes that districts used for counseling and library services and we obtained the related data. We used the data the districts provided to us to recalculate districts’ reported compliance rates to determine its effect, as Table 2 shows. Including support services in Instructor Salaries in the 50 percent calculation could increase compliance rates across the 10 districts we reviewed by 2.06 to 5.64 percentage points.2 However, because we did not perform an assessment of this information’s reliability and because of the limitations that footnote 2 describes, the percentage difference is not precise.

Nevertheless, several of the 10 districts we reviewed indicated that an improvement to the 50 Percent Law would be to include support service personnel, such as counselors and librarians, in Instructor Salaries in the 50 percent calculation. Representatives of faculty unions and academic senates that we spoke with also expressed openness to this change. However, these stakeholders asserted that if support service personnel, such as counselors and librarians are included in Instructor Salaries, the compliance rate should be increased above 50 percent. The representatives explained that increasing the compliance rate above 50 percent would allow districts to hire more faculty without taking away from the funding towards classroom instruction.

However, some of the districts we spoke with indicated that the compliance rate should not be increased. These districts explained that increasing the compliance rate would put more pressure on strained budgets to comply with the law. The Legislature could consider amending the law to include the salaries and benefits of support service personnel in Instructor Salaries, and if it does, it could consider increasing the required compliance rate as well. The Legislature could also consider allowing districts to exclude technology expenses related to instruction from the 50 percent calculation. In doing so, and if it passes legislation to address these considerations, the Legislature would help ensure that districts are able to invest in student support services while still complying with the required spending on instructors.

Most Districts That Track the Costs of Basic Needs Services Reported That Such Spending Had Only a Negligible Effect on Their Compliance With the 50 Percent Law

Although not directly included in our audit objectives, the Legislature asked that we review the effect that providing basic needs services and resources (basic needs services) has on districts’ ability to comply with the 50 Percent Law. Basic needs services can include, but are not limited to, food, housing, clothing, childcare, and mental health support. Access to basic needs services is important for student success. Although the districts we reviewed inconsistently tracked information on basic needs services spending, most districts reported spending on basic needs services and reported that spending on basic needs services does not significantly affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

The Chancellor’s Office’s accounting manual—which state law requires districts to follow—does not fully prescribe how districts should account for all basic needs services. Instead, the accounting manual states that, for certain programs, districts should identify and keep separate records of the receipt and expenditure of funds, and for other programs, districts may need to maintain detailed records to fulfill reporting requirements of other funding agencies. Because the accounting manual does not include a specific accounting code to track basic needs spending or specify which programs districts should include in the category of basic needs services, districts did not consistently track expenses for them, limiting our ability to report consistent information for the 10 districts we reviewed.

The amount of information each district was able to provide varied greatly, as did the districts’ approaches for tracking expenses for basic needs services. We asked each of the districts we reviewed to provide us with funding information for its spending on the basic needs services it provides to students. Nine of the 10 districts we reviewed were able to provide some information on basic needs spending, although not all could provide spending for both restricted and unrestricted funding sources. Of the nine districts that provided information, some provided expenses for one specific program but others provided spending for multiple programs that they considered to fall under basic needs services. For example, MiraCosta provided us with information for one specific program—Campus Assessment, Resources and Education program—which provides a holistic approach to help students succeed while addressing any challenges they may be experiencing in meeting their basic needs such as food, housing, transportation, mental health support, and childcare. In contrast, El Camino provided us with information related to several programs, such as the CalFresh Outreach Program, Student Food and Housing Support, Basic Needs Center, and Hunger‑Free Campus. Four districts—Merced, Napa, Rio Hondo, and Redwoods—could provide information about their spending on basic needs services from restricted funds but could not for such spending from the unrestricted general fund. Mt. San Antonio indicated that it provided expenses related to restricted funding programs specific to basic needs, but there are other restricted funding programs that it uses to provide basic needs services that are not included in the amounts provided due to the complexity of tracking those expenditures. San Diego could not provide information on basic needs services spending from either funding source. The district explained that it is difficult to show precisely how much it spent on basic needs services because such spending is spread across several accounting codes that are also used for other expenses.

Although districts reported information inconsistently, most districts indicated that they pay for their basic needs services programs primarily using restricted funds. Because the 50 percent calculation excludes expenses from restricted funds, the spending on these services does not affect districts’ compliance with the 50 Percent Law. For example, El Camino indicated that its basic needs services were funded exclusively using restricted funds. Further, San Diego, which could not provide basic needs services data to us, indicated that basic needs services are currently funded almost exclusively through restricted funds.

Districts we reviewed reported that their basic needs services spending from the unrestricted general fund could make up as much as 0.47 percent of the Current Educational Expenses or the denominator, as Table 3 shows. Some districts—for example, Los Rios and Mt. San Antonio—indicated that they spent unrestricted funding on basic needs services, which the 50 percent calculation includes, and basic needs services were 0.13 percent and 0.09 percent of the Current Educational Expenses that year, respectively. Further, MiraCosta indicated that 34 percent of its spending on basic needs services in fiscal year 2022–23 was from its unrestricted fund. This spending was 0.26 percent of the Current Educational Expenses of the 50 percent calculation in fiscal year 2022–23.

Because of inconsistencies in the data the districts provided, the Chancellor’s Office should update the accounting manual to fully prescribe how districts should account for basic needs services spending. This should include an accounting code for basic needs services and specify which basic needs services districts should classify under this code. Because of the importance of basic needs services for students, and the Legislature’s interest in the impact of basic needs services on districts’ compliance with the 50 Percent Law, districts should track this information. Further, some districts we reviewed indicated that if restricted funds become less available, districts may need to cut services, find other restricted funding, or use unrestricted funding, which could impact their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. When the Chancellor’s Office updates its accounting manual to specify how districts should track spending on basic needs services, the Legislature could require the Chancellor’s Office to report that data to it to better understand whether providing basic needs services will have a larger impact on their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

The Chancellor’s Office’s Limited Oversight Allowed Multiple Districts to Inaccurately Report Their Compliance Rates

Key Points

- From fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, only five of the 73 districts reported noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law.

- Insufficient guidance from the Chancellor’s Office may have caused some districts to inaccurately report their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

- Because most noncompliant districts are community supported, and do not receive funding through state apportionment, the Chancellor’s Office lacks a viable enforcement mechanism to hold noncompliant districts accountable.

Most Districts Reported Having Complied With the 50 Percent Law

From fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, 68 of the 73 districts reported to the Chancellor’s Office that they had complied with the 50 Percent Law in all five years, as Appendix B shows. Among the districts with the lowest compliance rates were San Mateo with 40.47 percent and Napa with 45.28 percent in fiscal year 2022–23. The districts with the highest reported compliance rates in fiscal year 2022–23 were Lassen with 58.65 percent and Feather River with 60.07 percent. The only districts that reported noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law in at least one of the last five fiscal years were Calbright, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, and San Mateo.

Although the districts generally report having complied with the law, all compliance is self‑reported by the districts to the Chancellor’s Office. State law requires the Chancellor’s Office to determine each districts’ 50 percent calculation based on the district’s reporting. By October 10 of each year, districts must submit to the Chancellor’s Office their annual financial and budget reports (financial reports). These financial reports include the dollar amounts districts report in Instructor Salaries, or the numerator of the calculation formula, and in the Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator of the calculation formula, and the amounts that districts exclude from the 50 percent calculation, such as expenditures from certain categorical or restricted funds. The Chancellor’s Office indicated that it relies on annual Certified Public Accountant (CPA) audits to gain confidence in the accuracy of the financial reports, including the 50 percent calculation, the districts submit.

Districts may adjust their financial reporting to achieve compliance with the 50 Percent Law. Some of the districts we reviewed adjusted their expense allocations, such as by moving expenses from the unrestricted general fund to a restricted or categorical funding source, which can help increase their 50 percent compliance rate by lowering the denominator. This included changing the funding source for previous purchases of instructional materials or utility payments to pay for the transactions from a restricted or categorical fund, which would remove the expense from Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator, and thereby increase their compliance rate by lowering the denominator of the calculation. These types of adjustments are allowable provided they conform to applicable law. The Chancellor’s Office provides guidance to districts that includes suggestions and guidelines to “fine tune” their 50 Percent Law reporting. This includes guidance on budgeting and charging costs to restricted funds, among other things. For example, the guidance directs districts to charge appropriate noninstructional costs to grants to move those expenditures to restricted funds, if those grants allow those types of expenditures. To ensure that districts achieve compliance—such as when a district is only a few percentage points below the required compliance rate—districts can use the guidance the Chancellor’s Office provides to fine tune their 50 percent calculation to ensure optimal use of the funds available to them.

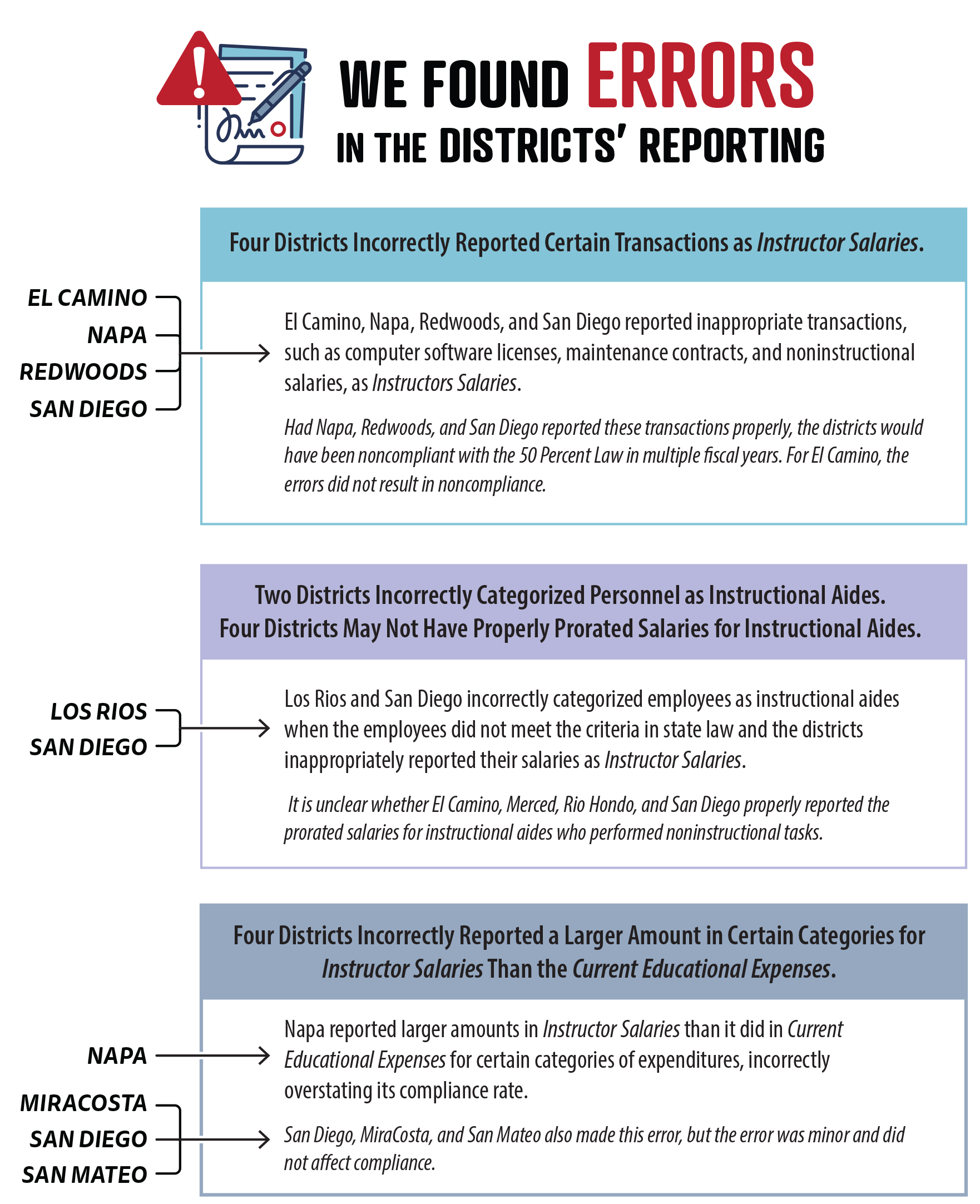

The Chancellor’s Office’s Inadequate Oversight Allowed Seven of 10 Districts We Reviewed to Inaccurately Report Their Compliance Rate

For the 10 districts we selected to determine whether they accurately reported their compliance with the 50 Percent Law, we reviewed a selection of 30 transactions that took place during five fiscal years at each of the 10 districts, for a total of 300 transactions.3 We selected transactions from different reporting categories, such as salaries related to instructional personnel and noninstructional personnel—like administrators and instructional aides—and other operating expenses. We also reviewed the calculations the districts used when producing their financial reports from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23 to determine whether they reported their compliance with the 50 Percent Law accurately to the Chancellor’s Office. Our review identified three types of errors in the districts’ reporting of their compliance with the 50 Percent Law, which we describe in Figure 5. Although the errors we identified in the districts’ reporting resulted in districts overstating their compliance rates, not all errors resulted in large enough changes to affect their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

Figure 5

Although Most Districts Report Compliance With the 50 Percent Law, Seven Districts We Reviewed Had Errors in Their Reporting

Source: Districts’ accounting records, supporting documentation, and 50 Percent Law compliance reports.

This figure depicts three boxes which describe the types of errors we found in districts’ reporting. The top box shows that El Camino, Napa, Redwoods, and San Diego reported inappropriate transactions, such as computer software licenses, maintenance contracts, and noninstructional salaries as Instructor Salaries. Had Napa, Redwoods, and San Diego reported these transactions properly, the districts would have been noncompliant with the 50 Percent Law in multiple fiscal years. For El Camino, the errors did not result in noncompliance. The second box shows that multiple districts incorrectly reported instructional aide expenses. Specifically, Los Rios and San Diego incorrectly categorized employees as Instructional Aides when the employees did not meet the criteria in state law and the districts inappropriately reported their salaries as Instructor Salaries. The second box also includes a statement that it is unclear whether El Camino, Merced, Rio Hondo, and San Diego properly reported the prorated salaries for Instructional Aides who performed noninstructional tasks. The third box shows that Napa reported amounts in certain categories for Instructor Salaries that were larger than the amounts it reported for Current Educational Expenses, contributing to the district falling out of compliance. San Diego, MiraCosta, and San Mateo also made this error, but the error was minor and did not affect compliance.

Insufficient Training by the Chancellor’s Office Led to Four Districts Incorrectly Reporting Certain Transactions as Instructor Salaries

As we show in the first error type in Figure 5, four districts—El Camino, Napa, Redwoods, and San Diego—incorrectly reported certain transactions as Instructor Salaries—or the numerator—of the 50 percent formula. Had the districts reported these transactions correctly, three of the districts would have been noncompliant with the 50 Percent Law. Districts report transactions into different categories when submitting their financial reports. One reporting category is Other Operating Expenses, which includes transactions for items such as contract services, utilities, and insurance. However, districts are only allowed to include some of these transactions in Instructor Salaries, or the numerator. Specifically, the Chancellor’s Office’s guidance indicates that only direct instructional costs associated with Instructional Service Agreements (ISA) from the Other Operating Expenses category should be included as Instructor Salaries. ISAs are contracts between a district and a public or private entity to provide courses to enrolled students, such as a district contracting with a local fire department to provide fire science training. However, El Camino, Napa, and Redwoods included transactions that did not meet these criteria for inclusion in Instructor Salaries, such as expenses for computer software licenses and maintenance contracts. Redwoods explained that it did not know that only direct instructional costs associated with ISAs should be included as Instructor Salaries. El Camino explained that the guidance from the Chancellor’s Office permits this type of reporting.

We reviewed the guidance and direction that the Chancellor’s Office’s provides to districts. Specifically, we reviewed the guidance the Chancellor’s Office provides to districts on how to report the Other Operating Expenses reporting category of Instructor Salaries on its website and the form the Chancellor’s Office created for districts to use in their financial reporting. Both the Chancellor’s Office’s website and the form specify that the only transactions districts can report as Instructor Salaries for the Other Operating Expenses reporting category are direct instructional costs associated with ISAs. A fiscal standards and accountability community college specialist (fiscal specialist) from the Chancellor’s Office also confirmed that districts should report only direct instructional costs associated with ISAs as Instructor Salaries. However, since Redwoods did not know the criteria for this reporting category and El Camino believed their reporting error was permissible, the guidance needs to be clearer and more training needs to be provided to districts to ensure that the districts are accurately reporting transactions for this category.

Another category of transactions that districts report as part of their financial reports is “Instructional Aides.” This category includes salaries for instructional aides, which districts may report as Instructor Salaries only for performing instructional tasks. As we discuss later, the Chancellor’s Office has not provided the districts with specific guidance about what constitutes “instructional tasks.” However, if an instructional aide performs a noninstructional task, then the districts should not report as Instructor Salaries the salary for that portion of the instructional aide’s work. One district—San Diego—reported instructional aide salaries as Instructor Salaries even though the district categorized the tasks those individuals performed as noninstructional, which the 50 Percent Law does not allow. For example, the district incorrectly reported tasks for institutional support services as Instructor Salaries. San Diego explained that it reported these transactions as Instructor Salaries based on training and guidance it received from its independent auditors and the Association for Chief Business Officials (ACBO).4 However, a fiscal specialist at the Chancellor’s Office indicated that this type of error would lead to inaccurate reporting.

We recalculated the four districts’ compliance rates taking into account these errors. We found that the compliance rates for three districts—Redwoods, Napa, and San Diego—fell below 50 percent in multiple fiscal years we reviewed, as Table 4 shows. The compliance rate for the fourth district—El Camino—remained above 50 percent. When we presented our conclusions to the districts, Redwoods and San Diego claimed that if the errors had been identified before they submitted their financial reports, they would have met compliance by adjusting other expenditures.

Two Districts Incorrectly Categorized Some Personnel as Instructional Aides, and Four Districts May Not Have Prorated Salaries for Instructional Aides for Noninstructional Tasks

During our testing of transactions at the 10 districts, we found that two districts incorrectly categorized noninstructional personnel as instructional aides, reporting their salaries as Instructor Salaries. The text box shows requirements in state law for a district to categorize personnel as instructional aides and to report their salaries as Instructor Salaries. San Diego and Los Rios were unable to demonstrate that transactions for instructional aides we tested met these criteria. For example, two transactions at Los Rios listed employees with the job title “senior IT technician,” and those employees’ job descriptions primarily describe technology support tasks. This job title neither designates the employee as an instructional aide nor denotes that the employee performs instructional tasks. As a result of these errors, the districts’ reporting to the Chancellor’s Office was inaccurate. For Los Rios and San Diego, these errors were not significant enough to cause the district’s compliance rate to fall below 50 percent for the years in which the transactions occurred.

Criteria for Reporting Instructional Aide Salaries as Instructor Salaries

1. Employee is assigned the basic title of “Instructional Aide” or other appropriate title that denotes that the employee’s duties include instructional tasks,

And

2. Employee is employed to assist instructors in the performance of their duties, in the supervision of students, and in the performance of instructional tasks,

And

3. The portion of instructional aide salaries for performing noninstructional tasks must be prorated and excluded from Instructor Salaries.

Source: State law.

In the absence of clear guidance from the Chancellor’s Office, we cannot determine whether four districts appropriately prorated the salaries of instructional aides for what appears to be noninstructional tasks as Instructor Salaries. As we explained previously, state law directs that the salaries of instructional aides who perform instructional tasks may be reported as Instructor Salaries. However, districts must prorate and exclude from Instructor Salaries the portion of their salaries for performing noninstructional tasks. In our testing, we identified that instructional aides at El Camino, Merced, Rio Hondo, and San Diego had job duties that may include noninstructional tasks. For example, two transactions at El Camino listed several employees with the job title “toolroom/instructional equipment technician,” but those employees’ job descriptions included various tasks that appear to be noninstructional, such as providing input during budget preparation and researching vendors when purchasing new and replacement equipment. However, the districts did not prorate the salaries of these instructional aides for their time spent on noninstructional tasks. Instead, the districts reported the entire salaries of these employees as Instructor Salaries.

We asked the Chancellor’s Office for clarification about its guidance related to these instructional aides and their time spent on noninstructional tasks. The Chancellor’s Office’s legal counsel explained that the determination of an employee’s instructional tasks is left to the discretion of the district. The legal counsel also stated that whether activities are instructional or noninstructional in nature would have to be determined by the totality of the circumstances given the particular employee’s job description. The Chancellor’s Office’s lack of guidance on what constitutes a noninstructional task could lead districts to incorrectly or inconsistently report instructional aide salaries for noninstructional tasks as Instructor Salaries, thereby incorrectly increasing their compliance rate.

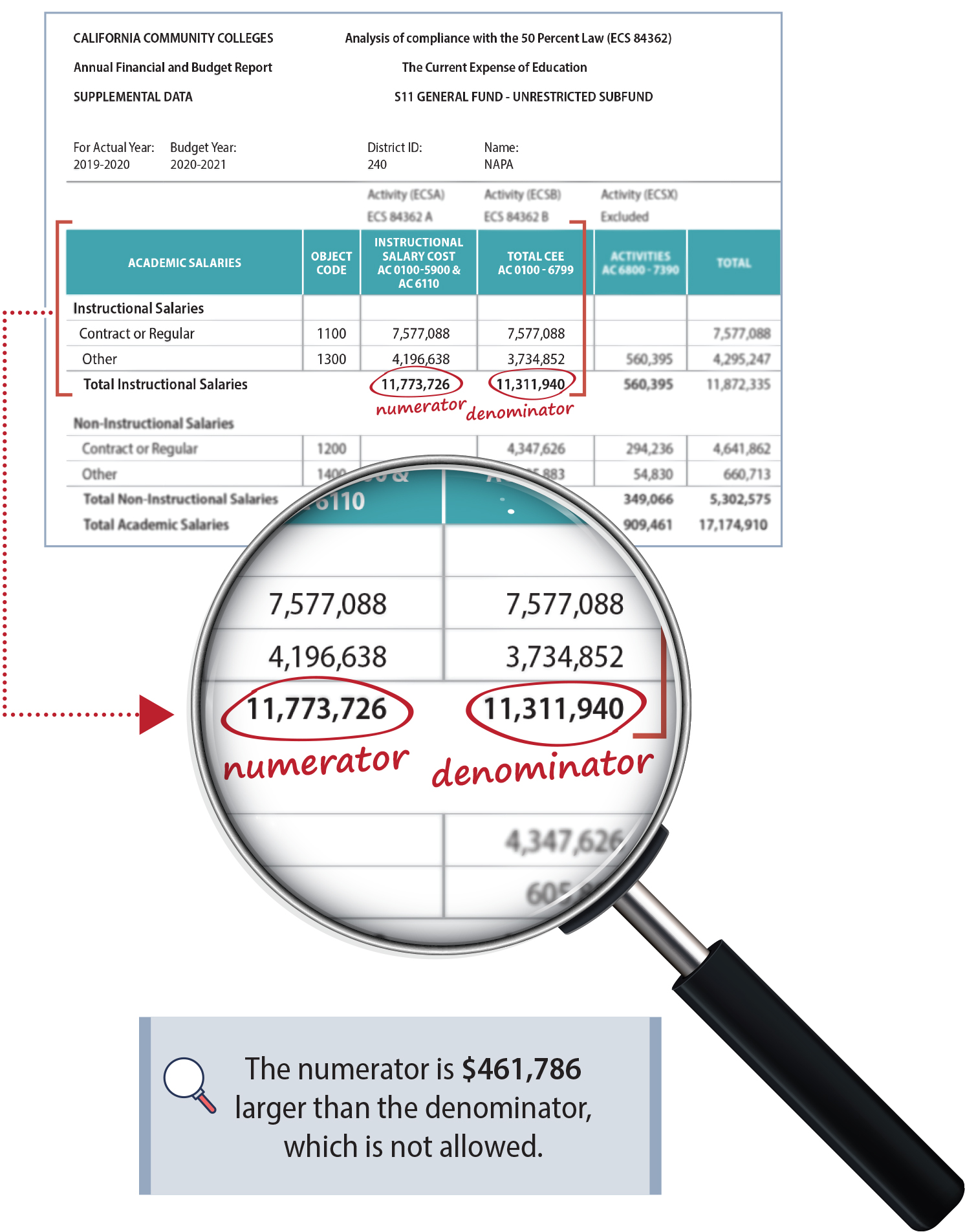

Because the Chancellor’s Office Does Not Review Financial Reports, It Did Not Identify Four Districts’ Incorrect Reporting

Four districts—MiraCosta, Napa, San Diego, and San Mateo—incorrectly reported a larger amount in certain categories for Instructor Salaries or the numerator, than in Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator, leading those districts to incorrectly overstate their compliance rates. The 50 Percent Law requires districts to also include in the Current Educational Expenses all transactions that are in Instructor Salaries. This means that a district cannot report a larger amount in Instructor Salaries than it reports in Current Educational Expenses. Doing so incorrectly leads to an overstated compliance rate. When we reviewed Napa’s financial reports, we saw that in fiscal year 2019–20 the district reported $461,786 in Instructor Salaries that it did not include in Current Educational Expenses, as Figure 6 shows. This error contributed to Napa becoming noncompliant with the 50 Percent Law in that fiscal year. Napa explained that the individual who submitted the report with this error no longer works for the district and the district was unable to locate documentation because of a cyberattack, all of which prevents it from identifying the cause of this error.

Figure 6

Napa Reported a Larger Amount in the Numerator of Its 50 Percent Formula Than It Did in the Denominator

Source: Napa’s fiscal year 2019–20 financial report.

This figure shows part of the financial and budget report submitted by Napa for fiscal year 2019-20. A magnifying glass calls attention to an error in Napa’s reporting where the district reported $11,773,726 in the numerator for instructional salaries and $11,311,940 in the denominator for instructional salaries. The numerator is $461,786 more than the denominator, which is not allowed.

Although we found that three other districts—MiraCosta, San Diego, and San Mateo—made similar errors, these errors were minor and did not affect the districts’ compliance with the law. San Diego explained that it believed that reporting transactions in Instructor Salaries but not in Current Educational Expenses was appropriate, although a fiscal specialist at the Chancellor’s Office indicated that this was not the proper way to report those transactions. Regardless, the Chancellor’s Office indicated that it does not verify the reported information on the districts’ financial reports because it relies on annual audits performed by CPAs. Had the Chancellor’s Office performed a simple review of the districts’ financial reports, it could have identified these errors just as we did.

The Law Is Unclear About the Use of Lottery Funds, Which Could Have Affected Two Districts’ Compliance Rates

Although improperly spending lottery funds is not a type of error we present in Figure 5, our review of a selection of transactions across the 10 districts caused us to question whether two districts properly spent proceeds from the California State Lottery Education Fund (lottery funds). Districts use various funding sources to pay for transactions during the course of a fiscal year. One such funding source that districts use is a quarterly allocation from lottery funds. State law prohibits the use of certain lottery funds for noninstructional purposes. However, two districts we reviewed, Redwoods and Mt. San Antonio, used lottery funds for utility payments and bank fees. We question whether these transactions are for an instructional purpose and therefore an allowable use of lottery funds.

The Chancellor’s Office categorizes lottery funds as a form of categorical aid or restricted funding, and districts must exclude categorical or restricted funds from their calculation when reporting their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. Because lottery funds are excluded from the 50 percent formula, the districts excluded these transactions from the 50 percent calculation. Had the districts instead used their unrestricted general fund to pay for these transactions, they would have included those transactions in Current Educational Expenses, or the denominator of the 50 percent formula, decreasing their compliance rate. Because the districts potentially used lottery funds for noninstructional purposes, this may have affected their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. However, Mt. San Antonio and Redwoods maintain that had they taken the approach of charging other support services instead of charging utilities to lottery funds, they still would have remained compliant.

The districts may have improperly spent lottery funds, in part, because of unclear guidance about what constitutes an expenditure for a noninstructional purpose. Specifically, until September 2024 when we pointed out to the Chancellor’s Office that state law prohibits the use of lottery funds for noninstructional purposes, the Chancellor’s Office’s website had improperly directed districts to use lottery funds to pay for noninstructional expenses, such as on energy and insurance. Further, in 2021 the Chancellor’s Office participated in a presentation at a conference for ACBO that stated this same incorrect guidance. Following our questioning of its website’s guidance, the Chancellor’s Office agreed that its guidance conflicted with state law and amended its website to remove this guidance. Nevertheless, Mt. San Antonio district maintains that using lottery funds to pay for utilities is appropriate. From the district’s perspective, utilities are used for instructional purposes, given that they ensure that instructional space, including classrooms and labs, are functional and suitable for the education of students. Mt. San Antonio noted, however, that it did not have an internal or external legal opinion on this topic. When we asked the Chancellor’s Office whether it agreed that using lottery funds to pay for utilities is using the funds for an instructional purpose, its general counsel stated that it had not issued a legal opinion on the matter and that districts have discretion on how they choose to use lottery funds as long as those uses are consistent with state law.

To gain further clarification about the appropriate use of lottery funds, we asked a representative from the California Department of Education (CDE), which also provides guidance on the use of lottery funds, whether the department would consider a district’s use of lottery funds to pay for utilities to be a noninstructional or instructional purpose. Similarly, CDE indicated that it does not provide advice on specific expenditures of lottery funds and that the use of lottery funds is solely at the discretion of the districts within state law parameters. Our office was unable to identify any definitions in state law for what constitutes an expenditure for instructional or noninstructional purposes in relation to districts’ use of lottery funds. The Chancellor’s Office’s lack of direction on whether spending lottery funds on utilities is for an instructional or noninstructional purpose, in combination with its former incorrect guidance, indicates that it needs to examine and issue additional direction about this matter in relation to the 50 percent calculation.

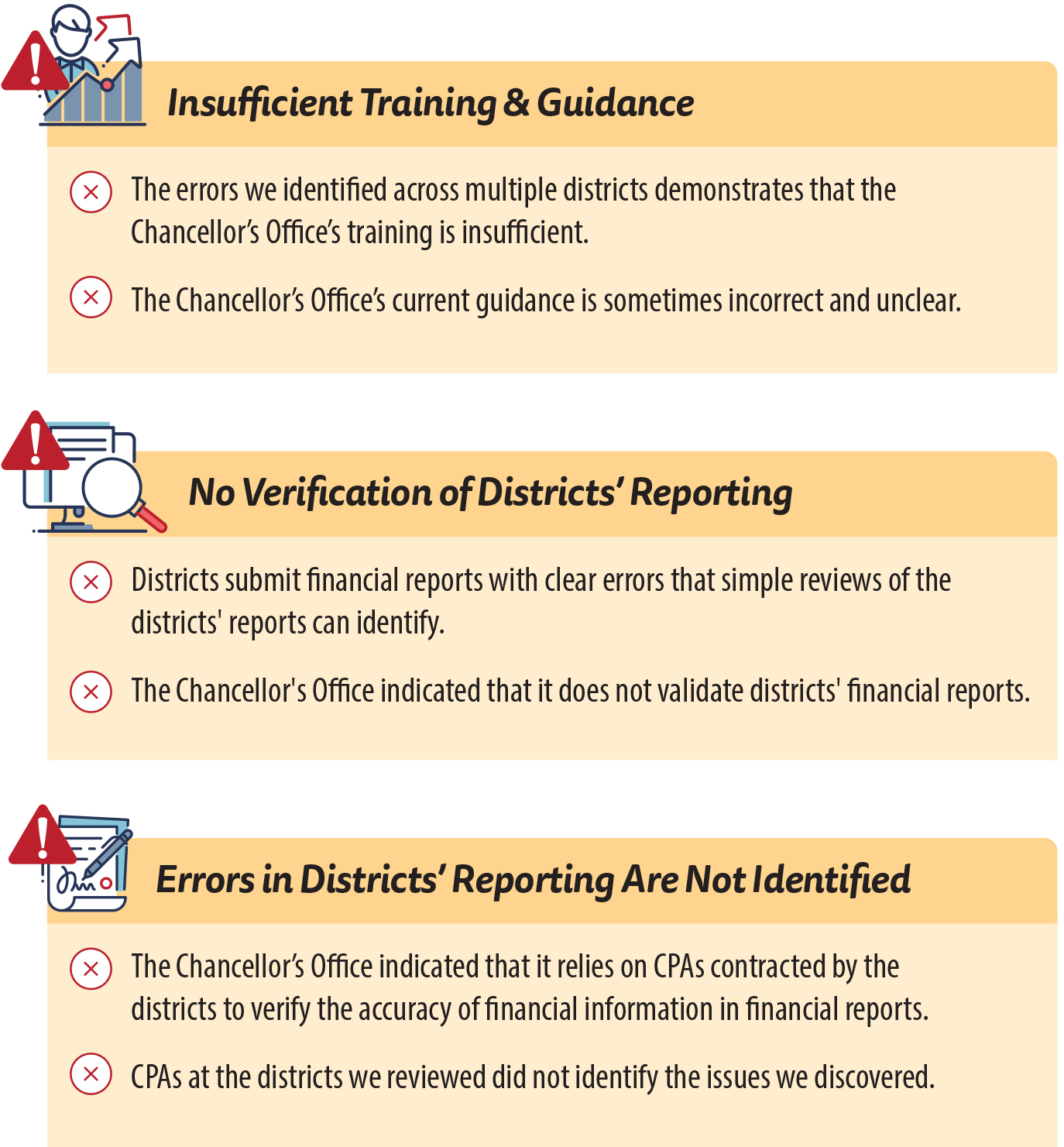

The Chancellor’s Office Must Improve the Training and Guidance It Provides to Districts Regarding Compliance With the 50 Percent Law

Because of the errors we identified in the districts’ reporting, we reviewed and assessed the training and guidance that the Chancellor’s Office provides to districts and interviewed Chancellor’s Office staff about its training and guidance. We found that the Chancellor’s Office’s training and guidance is insufficient and should be improved. Additionally, it does not perform its own review of districts’ financial reporting and the annual audits performed by CPAs that the Chancellor’s Office relies on did not catch the errors we identified. Figure 7 shows the results of our review.

Figure 7

Errors in District Reporting Can Be Attributed, in Part, to the Chancellor’s Office’s Limited Oversight of Districts’ Compliance With the 50 Percent Law

Source: Chancellor’s Office documents and auditor analysis.

This figure shows three boxes that illustrate the limited oversight provided by the Chancellor’s Office. From the top, the first box shows that the Chancellor’s Office’s training and guidance is insufficient. This box states the errors we identified across multiple districts demonstrates that the Chancellor’s Office training is insufficient and it further states that the Chancellor’s Office’s current guidance is inconsistent and unclear. The second box shows that the Chancellor’s Office performs no verification of districts’ reporting. It states that districts submit financial reports with clear errors that simple reviews of the districts’ reports can identify, and that the Chancellor’s Office indicated that it does not validate districts’ financial reports. The third box shows that errors in district reporting are not identified. It states that the Chancellor’s Office indicated that it relies on CPAs contracted by the districts to verify the accuracy of financial information in financial reports and that the CPAs at the districts we reviewed did not identify the issues we discovered.

A fiscal specialist at the Chancellor’s Office explained that it does not offer scheduled trainings to districts about reporting their compliance with the 50 Percent Law unless districts specifically request assistance. The fiscal specialist stated that instead ACBO provides trainings to district administration and CPAs at the twice‑annual ACBO conferences in which the 50 Percent Law is a frequent topic for workshops. The fiscal specialist further explained that the districts are responsible for interpreting and applying the law according to their own unique financial circumstances and that there is no one‑size‑fits‑all approach. She said that the Chancellor’s Office remains available to provide technical support upon request, ensuring that districts have the necessary support while upholding the principle of local governance and decision‑making. However, we disagree with this approach and believe it is insufficient when we consider the quantity and frequency of errors we identified. Furthermore, the lack of training is compounded by the sometimes unclear or incorrect guidance the Chancellor’s Office provides. As a result, the Chancellor’s Office should provide regular trainings to districts on reporting for the 50 Percent Law and should clarify its guidance to be clearer.

Further, we believe that the Chancellor’s Office should also perform its own review of the districts’ reporting of compliance with the 50 Percent Law, and it should update its guidance for the CPAs. The vice chancellor of college finance and facilities planning at the Chancellor’s Office explained that it does not have the capacity to audit and verify the information districts report in their financial reports. Each year, districts have all of their financial statements audited by CPAs. The CPAs then publish reports detailing the opinions of these audited financials. As a part of these audit reports, the CPAs publish opinions on districts’ compliance with various state laws, including the 50 Percent Law. We reviewed the 50 Percent Law portion of the audited financial reports CPAs published for the 10 selected districts for fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, and found that the CPAs did not identify the errors we identified.

The Chancellor’s Office’s Contracted District Audit Manual (audit manual) includes suggested audit procedures for the CPAs to perform related to the districts’ reporting of compliance with the 50 Percent Law. We spoke with two CPA firms—one of whom noted that it is an auditor of more than a third of the districts in the State—who explained that they perform all the suggested audit procedures. However, because the CPA firms did not identify the errors that we did in our review, it is clear that more needs to be done to ensure accurate reporting. The Chancellor’s Office should review and update its guidance in the audit manual where necessary for the CPAs to ensure that CPAs identify these errors. The Chancellor’s Office should also conduct its own review of the districts’ financial reports, such as reviewing the forms submitted by the districts to identify clear errors of misreporting and flag potential areas for concern.

We identified some of these same problems in an audit on this subject that our office issued 25 years ago. In our October 2000 report, California Community Colleges: Poor Oversight by the Chancellor’s Office Allows Districts to Incorrectly Report Their Level of Spending on Instructor Salaries, Report 2000‑103, we found that districts made errors in calculating their compliance with the 50 Percent Law. These errors included increasing the Instructor Salaries by including costs for noninstructional assignments and reducing the Current Educational Expenses by excluding activities that should have been included. In our October 2000 audit, we made eight recommendations to the Chancellor’s Office to address these errors. However, at the time of our current audit, the Chancellor’s Office had only fully implemented one recommendation from that audit: we had recommended that the Chancellor’s Office expand suggested audit procedures for district CPAs to detect errors in risky areas, such as instructor reassignments and exclusions from Current Educational Expenses, which it has done. When we asked the Chancellor’s Office about why it had fully implemented only one of our eight recommendations, a fiscal specialist at the Chancellor’s Office could not provide an explanation because historical records from the time of our October 2000 audit are not readily available. Nevertheless, the errors we identified in our previous report persist today, and the Chancellor’s Office must address them to ensure that districts accurately report their compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

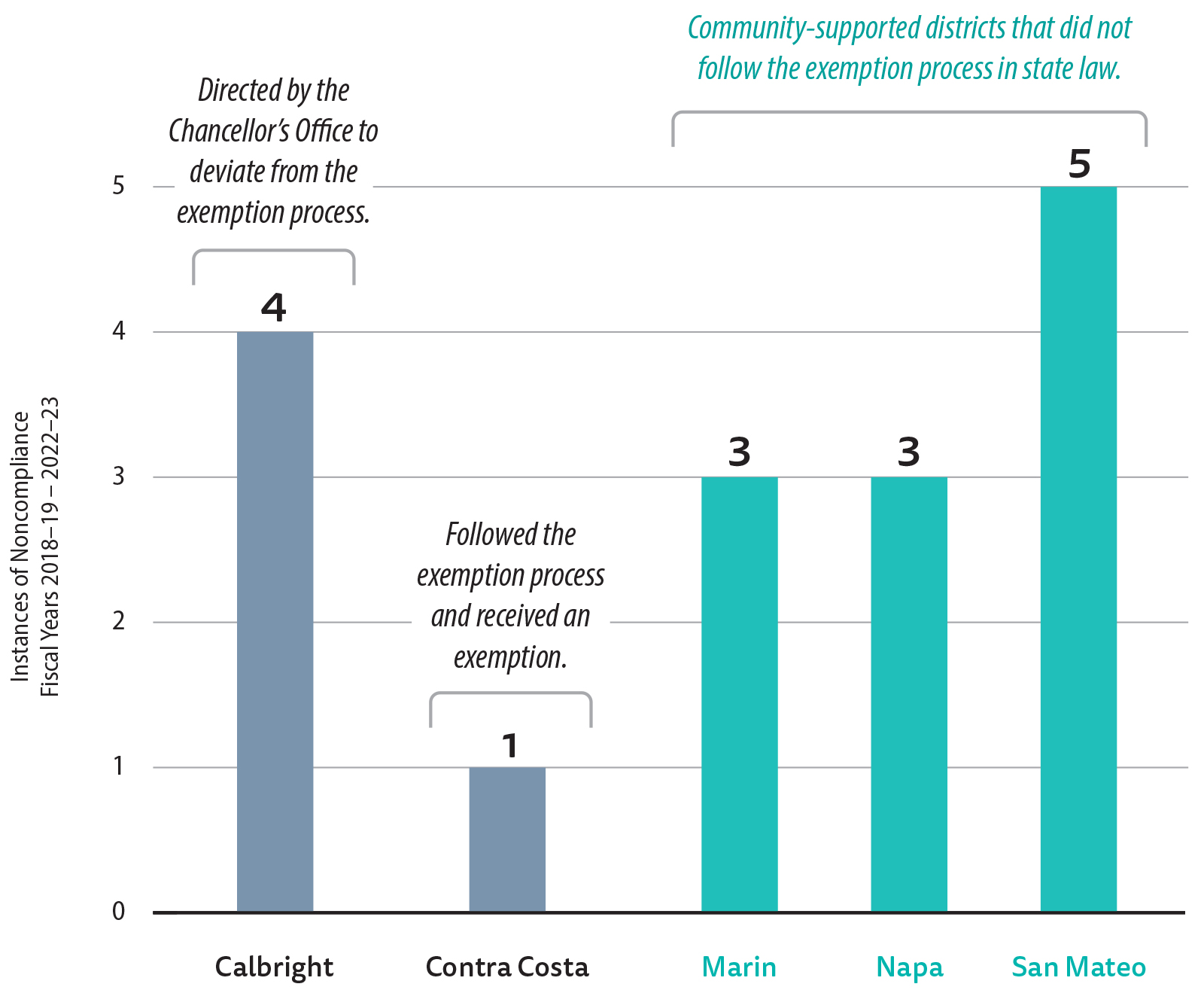

The Chancellor’s Office Has Not Followed Its Exemption Process and Lacks an Effective Mechanism for Holding Noncompliant Districts Accountable

During the last decade, the Chancellor’s Office has not required noncompliant districts to follow the process for filing an exemption request or a plan for achieving compliance (compliance plan). Five of the 73 districts reported they were noncompliant at least once from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, and four of those districts did not follow the exemption process. State law authorizes a district that does not comply with the 50 Percent Law to apply to the Chancellor’s Office for an exemption. Districts applying for an exemption must meet criteria established in state law, as we describe in the text box. If a noncompliant district does not receive an exemption from the CCC Board of Governors, state law requires that it submit a compliance plan detailing how it will spend the deficient amount for Instructor Salaries during the next fiscal year. The deficient amount is the nonexempt amount by which the district fell short on spending on Instructor Salaries to comply with the 50 Percent Law. Districts that fail to comply with the 50 Percent Law risk losing part of their state apportionment equivalent to the deficient amount. Despite these requirements, according to a fiscal specialist from the Chancellor’s Office, the Chancellor’s Office has not withheld any district’s apportionment during the last decade because of noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law.

Exemptions From the 50 Percent Law Require the District to Demonstrate Serious Hardship or That Compliance Would Result in the Payment of Classroom Instructor Salaries in Excess of Those Paid by Comparable Districts

Serious hardship are conditions under which:

- Complying with the 50 Percent Law would have prevented the district from discharging financial liabilities.

- The first year of new funding resulted in the district’s inability to meet the requirements of the 50 Percent Law.

- Unanticipated, unbudgeted, and necessary spending prevented compliance with the 50 Percent Law.

- The district has expended funds with the agreement of the district’s academic employee representative or, if none exists, the academic senate, and the district can document the necessity of, and adverse impact of not spending, the funds.

A district will be considered to have paid salaries in excess of those paid by comparable districts when, among other requirements, its spending on salaries of classroom instructors exceeds those of other districts of comparable type and functioning under comparable conditions.

Source: State law.

We identified five of the 73 districts that were responsible for a total of 16 instances in which a district reported noncompliance with the 50 Percent Law from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23. State law requires a noncompliant district seeking an exemption to file an initial exemption application by September 15 following the year of noncompliance. The initial exemption application serves as a notification to the Chancellor’s Office that the district may not meet compliance with the 50 Percent Law and marks the beginning of a two‑step process.

According to the Chancellor’s Office, the first step of the exemption process entails the Chancellor’s Office offering guidance to the district aimed at improving various aspects of the district’s accounting practices, such as expense allocation, accounting code usage, and fund optimization, to help bring the district into compliance with the 50 Percent Law. If, after these efforts, a district determines that it is still noncompliant, the second step is for the district to proceed with the exemption process by submitting to the Chancellor’s Office a second exemption form along with additional supporting information. The additional supporting information must explain how the district’s exemption request meets the applicable requirements, such as by indicating how certain costs qualify as “serious hardship” and by certifying that the district has provided a copy of the application to the exclusive representative of the district’s academic employees and the district or college academic senate. The CCC Board of Governors is responsible for approving exemption requests.5 Only one district, Contra Costa, followed the entire exemption process in fiscal year 2021–22, including submitting the exemption forms and additional supporting information, and it ultimately received an exemption for serious hardship.

Another district, Calbright, was responsible for four of the 16 instances, but the Chancellor’s Office did not require that it follow the exemption process. In 2018, the State created the California Online Community College District, later named Calbright College, to provide working adults access to high‑quality, affordable, and flexible opportunities to pursue postsecondary education. From fiscal years 2019–20 through 2022–23, Calbright’s reported compliance rate ranged from zero to nearly 6 percent, and the district’s annual audits found it to be out of compliance, noting that it did not apply for an exemption in those years as state law requires. In 2022, the Chancellor’s Office issued a letter granting Calbright an exemption from complying with the 50 Percent Law, citing the college’s lack of accreditation and its ongoing development of educational programs and its hiring of instructional faculty. As the Chancellor’s Office’s general counsel explained to us, Calbright received the exemption because it was in its start‑up phase and did not receive state apportionment. In the exemption letter, the Chancellor’s Office also explained that it would allow the district to deviate from the exemption process established in law by not requiring Calbright to submit the second exemption application. When we asked for the legal basis allowing the Chancellor’s Office to exempt Calbright from having to submit the second exemption application, the Chancellor’s Office’s general counsel did not provide one but informed us that going forward it will require Calbright to follow the two‑step exemption process prescribed in law.

The Chancellor’s Office did not require noncompliant districts to submit compliance plans with the requisite information. In the remaining 11 of the 16 instances in which districts did not comply with the 50 Percent Law, the three noncompliant districts did not file for an exemption and were therefore required to submit compliance plans in accordance with state law. In all 11 instances, the districts were community‑supported districts: Marin, Napa, and San Mateo. San Mateo is responsible for five instances, as Figure 8 shows. However, in each instance these districts either did not file a plan, or filed plans that did not detail how those districts intend to spend the deficient amount in the next fiscal year to become compliant. Although the Chancellor’s Office’s letter to districts requesting compliance plans directs the districts to include any details on any plans and activities that the district has in place to resolve the deficiency, the Chancellor’s Office does not instruct the districts to develop a plan as to how the deficient amount will be expended for salaries of classroom instructors during the next fiscal year, as required by state law. As a result, the Chancellor’s Office continues to accept insufficient plans that do not commit to correcting any deficiency.

Figure 8

Most Districts That Were Noncompliant With the 50 Percent Law Did Not Follow the Exemption Process in State Law